8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

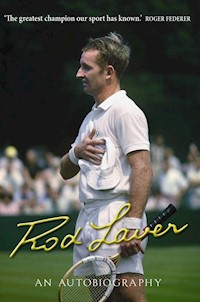

'From my earliest tennis memories, Rod Laver stood above all others as the greatest champion our sport has known.' Roger Federer Rod Laver's autobiography tells the inspiring story of how a diminutive, left-handed, red-headed country boy became one of the greatest ever sporting champions. Rod was a dominant force in world tennis for almost two decades, playing and defeating some of the greatest players of the twentieth century. In 1962, Rod became the second man to win the Grand Slam - that is, winning the Australian, French, Wimbledon and US titles in a single calendar year. In 1969 he won it again, becoming the only player ever to win the Grand Slam twice. His book is a wonderfully nostalgic journey, transporting readers from the early days of growing up in an Australian country town in the 1950s, to breaking into the amateur circuit, to the extraordinary highs of Grand Slam victories. Away from on-court triumphs, Rod also writes movingly about the life-changing stroke he suffered in 1998, and of his beloved wife of more than 40 years, Mary, who died in 2012 after a long illness. Filled with anecdotes about the great players and great matches, set against the backdrop of a tennis world changing from rigid amateurism to the professional game we recognise today, this is a warm, insightful and fascinating account of a great sportsman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Rod Laverwith Larry Writer

First published in Australia in 2013 by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Rodney Laver 2013

The moral right of Rodney Laver to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ Phone: 020 7269 1610 Fax: 020 7430 0916 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 76011 124 3

eISBN 978 1 74343 775 9

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

For Mary and my family

Contents

Foreword by Roger Federer

Acknowledgements

Acronyms

1 Bush boy

2 Charlie and Hop

3 Innocent abroad

4 Into the cauldron

5 Breaking through

6 Winning Wimbledon

7 Daring to dream

8 My first Grand Slam

9 The gypsy years

10 If it’s Tuesday . . . this must be Khartoum

11 Love match

12 The open tennis revolution

13 Grand Slam II

14 Back to earth

15 Money-go-round

16 For Australia

17 Winding down

18 New horizons

19 Struck down

20 The ultimate honour

21 Life’s passing parade

Forewordby Roger Federer

IF YOU REALLY LOVE THE SPORT YOU PLAY THEN YOU MUST study its history to understand how it has evolved into the sport we know today.

Few sports have a longer or richer history than tennis and no player occupies a bigger part of that history than Rod Laver. From my earliest tennis memories, Rod ‘the Rocket’ Laver stood above all others as the greatest champion our sport has known.

Winning all four majors in the same calendar year to complete the Grand Slam, on two separate occasions no less, is one of the greatest feats a player can accomplish. In 1962, Rod became only the second man to do this. Seven years later, Rod conquered the game’s Everest again to become the first player – man or woman – to have won the Grand Slam for a second time. No male player has completed the Grand Slam since.

When you consider the greats who have graced the world circuit since Rod’s second Slam in 1969 – Connors, Borg, McEnroe, Becker, Edberg, Lendl, Sampras, Agassi, Nadal and Djokovic – you realise just how hard it is to do. Three of us, Andre, Rafa and myself, have won all four majors but not in the same year.

This monumental achievement is what sets Rod Laver apart. This is his unique contribution to tennis history.

It wasn’t until the Australian Open in January of 2006 that I actually met Rod. It was just a few days before that well-recorded occasion when, in front of 15,000 screaming centre court fans and a worldwide television audience, I broke down and cried just after Rod presented me with the Sir Norman Brookes Challenge Cup.

I was pretty relaxed but certainly tired after winning the match. When they called my name to collect the trophy from Rod Laver, in that great Melbourne Park stadium that bears his name, the magnitude of the moment finally hit me. I realised how fortunate I was to be presented the Norman Brookes trophy by Rod himself. This was a moment I will never forget.

There is a footnote to these events. At our first meeting on the Tuesday before the final, Rod and I had a chance to get to know each other. We discussed my shyness early in my career. Similarly, Rod mentioned that he, too, was shy as a young player. It was at this moment that I realised Rod and I had a lot of similarities, and I really felt comfortable in his presence.

Seeing this, my then coach and good friend of Rod’s, Tony Roche, arranged for Rod and me to get together after my quarter-final and semi-final matches. Tony had told me so many classic stories about Rod and the good old times from his playing days, so it was really great to be able to hear some of those experiences directly from Rod. It was very inspiring meeting someone like Rod, who is such an important part of the fabric and legacy of our sport. There is no doubt my chats with Rod over those few days gave me added impetus and inspiration in my quest for back to back Australian Open crowns.

Since those heady moments in Melbourne, Rod has witnessed my two most recent Wimbledon final victories – the marathon five setter against Andy Roddick in 2009 and then against Andy Murray in 2012. I wouldn’t presume to call Rod my lucky charm, but his presence at any tournament is not only motivational – it also helps to bring out the best in my game. I have always appreciated it when the greats come back to the arenas in which we play, but Rod’s presence is always incredibly special.

Rod retired from the circuit just a few years before I was born so I never witnessed his exquisite skills live. I have watched film of him playing in finals and was mesmerised by his all-round game and incomparable court coverage. Rod seemed to have no weaknesses and while always a true sportsman on court, he was also a man of steely determination, and was incredibly strong under pressure. Rod always brought his best game to the big stage, whether it was a Grand Slam or a Davis Cup final.

Rod changed from being an amateur player to a professional one, aged 24, after claiming the Grand Slam in 1962. As a result he was ineligible to play in the amateur-only grand slam championships – the Australian, the French, Wimbledon and the US – until a few months before his 30th birthday in 1968, when these tournaments became open to professionals as well as amateurs. In the interim Rod missed playing for 21 grand slam titles. We can only guess how many of these he might have won.

Rod made a huge contribution to the game of tennis over his 22-year career, which started in 1956. His enormous talent was largely responsible for changing the way tennis was played. For example, Rod was the first player to master and consistently use hard hit top spin on both his forehand and backhand sides. For a left hander this was exceptional because, before the Rocket started wielding that massive left arm, no southpaw had been able to perfect the top-spin shot off the backhand side. So this was quite a feat, given the small head on those old wooden racquets. By this time Rod was on the path to becoming the No. 1 player in the world. Every other player realised they would have to eventually emulate his top-spin skills or be left behind. The result was that by the time the 1970s were in full swing, it was virtually impossible to win a big tournament unless you hit top spin like it was second nature. Rod Laver literally forced others to change the way they played the game and rethink their own playing style, technique and tactics.

Rod was also a primary catalyst for the introduction of open tennis in 1968, which completely revolutionised the structure of world tennis and, in turn, changed the game forever. By the second half of the 1960s, Rod was universally recognised as the best player in the world, with his closest rivals for that mantle being mainly drawn from the professional ranks, including the great Pancho Gonzalez and Australian stars like Lew Hoad (Rod’s own hero) and Ken Rosewall. As a result, the separation of the professional players from the amateur-only grand slam tournaments was becoming increasingly intolerable to anyone who had the best interest of tennis at heart.

The four grand slam events were beginning to lose their lustre as a result of not having all the best players compete. Many of the amateur officials were hugely resistant to change for fear of losing their influence and, often, total control of their country’s players. So it is to the eternal credit of a few forward-thinking tennis administrators – notably Herman David, the chairman of the All England Club – that the momentous decision was taken to introduce open tennis in 1968. This breathed renewed life into the game and enabled the continuing evolution of tennis into the great world sport it is today. Tennis had entered the modern era and Rod had played his part.

Rod is quite simply one of the nicest individuals I have ever met. He is warm, generous and good-humoured. He conducts himself with an endearing humility that promotes his status as not only a tennis great but a genuine legend of world sport.

Family comes first with Rod, and my wife Mirka and I have the deepest admiration for Rod’s absolute devotion in caring for his beloved wife, Mary, during her final years. His personal attributes of total commitment and inner strength were in play once again. Previously, Mary had been instrumental in Rod’s recovery from a debilitating stroke in 1998 and Rod reciprocated in full, until her passing in November 2012.

In the following pages, Rod tells the extraordinary story of a talented but shy freckle-faced kid from outback Queensland who, with the right support from the right people at the right time, was able to fulfil his father’s dream of having a son win Wimbledon and then go on to become the world’s greatest tennis player.

Rod loves tennis and everything about it and this shines through on every page. After you’ve finished reading his story, you will understand so much more about the game we love.

Roger Federer September 2013

Acknowledgements

So many friends and colleagues made wonderful contributions to this book, and to the life and career in tennis that it chronicles. Thank you to you all, and to anyone else I’ve inadvertently omitted.

Larry Writer came to my home in Carlsbad, California, over some weeks in October 2012 armed with a tape recorder and hundreds of questions that made it easy, and a pleasure, to talk about the events of my life. Then Larry helped me to put my memories and thoughts into the words that you are about to read.

My gratitude to my manager Stephen Walter, a fine man and a dedicated one, who has always had my best interests at heart.

There is no more knowledgeable tennis man than Geoff Pollard, vice-president of the International Tennis Federation, president of the Oceania Tennis Federation, chairman of the ITF Rules of Tennis Committee and Technical Commission, and president of Tennis Australia from 1989–2010, and I thank Geoff for reading the text for accuracy and making invaluable suggestions and amendments.

The tennis skills and winning mentality bestowed upon me by my coaches, the late Charlie Hollis and Harry Hopman, are detailed in the pages that follow. Suffice to say that without those special men I could never have been the player I was.

For their camaraderie and fair but ferocious competition I thank my peers from Australia’s golden age of tennis: Ashley Cooper, Roy Emerson, Neale Fraser, the late Lew Hoad, John Newcombe, Tony Roche, Ken Rosewall, Frank Sedgman and Fred Stolle. I also pay tribute to their wives: Helen Cooper, Joy Emerson, Thea Neale, Jenny Hoad, Angie Newcombe, Sue Roche, Wilma Rosewall, Jean Sedgman and Pat Stolle. A cheer, too, to non-Aussies Charlie and Shireen Pasarell, Butch and Marilyn Buchholz, Ray and Susan Moore, and Cliff Drysdale. I thank my friends the late Frank Gorman, Jim Shepherd, and the late Mr and Mrs Cereal Shepherd, who took me under their wing when I was young.

John and Roberta McDonald are friends who have given generously of their wisdom, friendship and tennis knowledge. It was John who introduced me to his mate the late Charlton Heston and his wife Lydia, for whom nothing was too much trouble. Chuck Heston showed me and the other tennis players of the day that movie stars can be as in awe of sports champions as we are of them.

I thank the author and businessman Robert Edsel for his friendship and his inspiration. I am similarly in the debt of my old friends Tony Godsick, who now has the honour of managing Roger Federer, and his wife Mary Jo Fernandez.

What an honour it is that the great Roger Federer has taken time out from his peerless career to pen the foreword to this book. I appreciate and am humbled by Roger’s kind and generous words. For her friendship and kindness, too, I thank Roger’s wife Mirka.

I am so grateful to my sponsors Rolex, Adidas and the ANZ Bank. They have had my back through thick and thin. The ANZ was my first bank as a lad, the rosewood Rolex I treated myself to three decades ago has not missed a beat and Adidas has been producing the Rod Laver shoe for more than 40 years. We have history.

Bud Collins happens to be one of the finest tennis writers and personalities who ever lived. I’m proud to count Bud and his wife Anita as friends. In 1971 Bud and I collaborated on The Education of a Tennis Player, a book of which I am very proud and which was a wonderful resource for this memoir, each page jogging my memory as I looked back into the past.

Without the belief, guts and know-how of the late sports promoter and businessman Lamar Hunt and his son-in-law Al Hill Jr, professional tennis as we know it could never have happened. We all owe a debt to Lamar and Al, and to Lamar’s wife Norma.

In the gypsy pro years, a promoter with integrity who staged his events professionally and didn’t skip town before his players were paid was worth his weight in gold. Pat Hughes was one such promoter, as well as an excellent player and Dunlop sports administrator in London.

IMG, headed by the late Mark McCormack and with Jay Lafave as my representative, for many years managed my career to perfection.

I admired the late Adrian Quest as a tennis player and a tennis journalist. I thank him for his lifelong support and wisdom. I am grateful, too, to all the other fine tennis writers who covered my career accurately and with insight.

Thank you to Chris Clouser, friend, businessman and chairman of the International Tennis Hall of Fame at Newport, Rhode Island. He and his wife Patti have been staunch allies.

The Wimbledon championships were, and remain, special to me, and under the chairmanship of Philip Brook, the All England Tennis Club is in the very best of hands. As are the Australian championships, with Steve Wood as chief executive officer of Tennis Australia.

I thank Wick Simmons and his wife Sloane. Wick, chairman of Nasdaq Stock Market Inc. and former president of Shearson Lehmann and Prudential Securities, gave great, much-needed business advice, and was a good friend and tennis partner.

Tom Gross gave wonderful service as an instructor with Laver–Emerson Tennis Holidays and is still one of the best MCs in the business.

For helping to make this book a reality, I thank John Tall for so generously and painstakingly sourcing and supplying many of the photographs that grace this book, Jennie Fairs for her meticulous research, and Tom Gilliatt, director and non-fiction publisher, and Jo Lyons, editor, of Pan Macmillan, my publisher. Thanks also to publicists Tracey Cheetham and Eve Jackson. For putting Stephen Walter and me in touch with Pan Macmillan in the first place, I owe a debt to the fine Australian writer Les Carlyon.

Last, and most of all, I thank my much-loved, much-missed wife, the late Mary Laver, for her love and her courage, for sharing my life journey, for broadening my horizons, and for helping me to understand that there is more to life than tennis and that family is everything. Love, too, to my son Rick, his wife Sue and their daughter and my grand-daughter Riley. Loving thoughts also to my late parents, Roy and Melba, and brother Bob, to my sister Lois and her husband Vic, and my brother Trevor and Trevor’s wife Betty, whose marvellous and encyclopaedic self-published recounting of my career, The Red-Headed Rocket from Rockhampton, was as affectionate as it was accurate and, like The Education of a Tennis Player, a priceless resource for this book. Another of Betty’s blessings is her wonderful work scouring the Laver photograph albums to find many of the candid family shots in our photo sections. And by welcoming me into their lives, Mary’s children Ann Marie Bennett and Ron and Stephen Benson, Ann Marie’s husband Kipp and Ron’s wife Julie have given me a gift I treasure.

Acronyms

ATP

Association of Tennis Professionals

ILTF

International Lawn Tennis Federation

ILTPA

International Lawn Tennis Players Association, later changed to International Tennis Players Association

IMG

International Management Group

IPA

International Players Association

IPTPA

International Professional Tennis Players Association (LA)

ITPA

International Tennis Players Association

LET

Laver–Emerson Tennis

LTA

Lawn Tennis Association (Yugoslavia)

LTAA

Lawn Tennis Association of Australia

NTL

National Tennis League

WCT

World Championship Tennis

Chapter 1Bush boy

TENNIS WAS A BIG PART OF MY LIFE FROM AS FAR BACK AS I can remember. What else was a kid to do? Growing up in those years when my family and I were moving around rural Queensland, I can’t remember a house, backyard or paddock that wasn’t littered with tennis racquets and tennis balls . . . along with, of course, footballs, cricket bats and six stitchers. And it wasn’t just me. If you lived in Australia in the ’40s and ’50s, those golden, more innocent times before the public tennis courts that were ubiquitous on Australia’s rural and suburban blocks were banished by houses, flats, offices, parking lots, factories and shopping malls, tennis was what you played. It was every bit as much a national pastime as cricket, footy and swimming. A tennis racquet was as prevalent in a boy’s life then as PlayStations, iPods and mobile phones are today. That being so, and with tennis-mad parents, brothers, in-laws and mates like mine, I had little choice but to play the game.

I was born on 9 August 1938, just one month before the American Donald Budge won the first ever tennis Grand Slam, in Rockhampton’s Tannachy Hospital, the third child of Melba (named after Dame Nellie, naturally) and Roy Laver. My brother Trevor was six years older and Bob had four years on me. Sister Lois arrived nine years after I came along. Dad was a cattleman, a loving, caring father but, like most bushies, a tough, hard bloke who treated his own farm injuries (mainly because there was no hospital handy). Home for us was Langdale, a 9300-hectare cattle property an hour’s drive from the town of Marlborough, which is 96 kilometres north of Rocky. My father, who was raised in Gippsland, Victoria, was one of 13 kids, eight of them boys, so the Laver brothers were able to field the best part of a cricket or football team and four tennis doubles teams in local comps. My mother also hailed from a sporting family, the Roffeys. Mum’s mother, Alice Roffey, rode horses until she passed away at age 90.

Queenslanders have always been tough, self-reliant people, but, apart from the heat, tropical rain and those beautiful old wide-verandah Queenslander homes, rural Queensland in the 1940s would be all but unrecognisable to anyone who has known it only in modern times. Most roads were unsealed, and I remember kangaroos bounding alongside the family car as we travelled the long distances from town to town, farm to farm. When I was a boy, with World War II being waged, the federal government introduced measures to aid the war effort. There were blackouts and brownouts in the cities and larger towns to deter Japanese air raids, food was rationed and fun was too, with sporting events confined to weekends. Mum and Dad had to carry personal ID cards. There were fewer blokes about because many were serving overseas. Short back and sides was the hairstyle of choice for Queensland men, the vast majority of whom smoked rollies and wore wide-brimmed felt hats and suit coats in a heatwave.

There was no TV back then, so radio was the main source of entertainment and war news. The newsreel that was screened before the cartoons and the double movie bill at the local picture theatre was another way of keeping up to date with how we were faring against the Germans and Japanese. Churches on Sundays were full to brimming. After church, people gathered in the church hall to devour sandwiches and tea and talk about the weather and its effect on crops, after which it was home for a Sunday roast with family and friends, no matter how hot the day. Eating out on a Sunday was impossible for the simple reason that pubs and cafes were not allowed to open on the Sabbath. Other days, when restaurants were open, proprietors insisted that male patrons wear a collar and tie. Lew Hoad told me how difficult it was to dine out when he was a young player travelling the rural Queensland tournament circuit. He said he was routinely abused and denied entry by restaurant staff if he entered dressed casually. Dressing to the nines can be a challenge when you’re living out of a suitcase.

When I was a toddler, Dad’s favourite sport was tennis and he was determined that it become ours. To this end my brothers carted great quantities of ant bed – you knock over an ant hill and crush the pebbles into smooth, hard grit, which plays a little like fast clay – and loam, laid it in the yard, surrounded it with a wire perimeter fence, erected a net, scratched out some markings . . . and we had our own tennis court. We rolled and watered it every day to stop it from cracking, or being washed or blown into the next paddock by rain or wind. That upkeep was a small price to pay given the fun we had on that ant-bed court. There was no quarter given or asked when I got a little older and played against my brothers, or against my parents for that matter, and making it even more interesting was that the court’s bounce was anything but true so you had no clue where the ball was going to go. Centre court at Wimbledon it was not.

What with tennis on our makeshift court, backyard cricket in wide, grassy paddocks and doing my lessons – reluctantly, I have to admit – by correspondence, life was idyllic on the property for the Laver boys, little blokes with sun hats, T-shirts, shorts and no shoes. With my flaming hair, sticking-out ears and 49,000 freckles, I’m told I was the spitting image of Ginger Meggs in the Sunday newspaper comics. We hunted kangaroos and rode horses, playing at being cowboys. That Langdale paddock became the endless plains of the wild west, even though horses and I got off to an unfortunate start. When I was two, Dad lifted me up into the saddle of one of our horses and led it across the paddock but somewhere along the way I fell off without my father realising and when he reached the stable and saw the empty saddle he hightailed it back to retrieve me.

Life was everything a boy could wish for, so we were not pleased when Dad, who wasn’t the only one finding it tough to make ends meet on the land, took us off the property and relocated us all to a house in the backblocks of Marlborough, where he’d found work as a butcher. Trevor, Bob and I attended the tiny local school where I excelled at tennis against my school mates – though unlike my tennis pals, schoolwork got the better of me.

When I was 10, we moved again, to Rockhampton, because Dad, now in his 50s, could make more money butchering in a bigger town. Besides, he and Mum believed my brothers and I would receive a better education at Rockhampton Grammar School than at Marlborough. And, even more importantly, there was a well-organised tennis competition at the Rockhampton Association courts, where my parents played mixed doubles, and my brothers and I singles and doubles. It was about then that I realised I had a better-than-ordinary talent to follow and strike a tennis ball, and being naturally left-handed probably helped me too because lefties were in the minority so I was awkward for others to play against.

We lived on Lakes Creek Road for a while and then moved to a Queenslander in Main Street Park Avenue. I’m told I had a thing for climbing up onto the roof of our house and sitting there, only coming down when I got hungry. I was at Rocky Grammar for three years and then finished my primary education at Park Avenue School near our home before following Trevor and Bob to Rockhampton High School, which they left after completing the first two years. Trev then worked in our cousin Len Laver’s sports store and Bob, much to everyone’s envy, got a job at Paul’s Ice Cream Works.

Right through school, I was a handy cricketer, a batsman and a left-arm spinner who bowled leg breaks. One afternoon when I was 11, I came home after playing cricket for my school and when Trevor asked me how I’d fared I said, ‘Oh, okay, I guess, I took nine wickets for seven runs.’ I wasn’t being modest, it was just no big deal for me. I don’t think I even realised these were amazing figures. As far as I was concerned I’d just had a good day and a whole lot of fun.

I was a keen fisherman, sitting for hours on the banks of the Fitzroy River and often returning home in the gathering dusk with a sugar bag filled with fish for dinner. I hear that fishing is one of the most dangerous of pastimes and it certainly proved hazardous for me when, after netting barramundi in the Fitzroy, I suffered a mishap that easily could have ruined my tennis career. I was absent-mindedly digging my fish-cleaning knife into the sand when it hit a rock and somehow the blade sliced into my left hand, my racquet hand, and severed the tendon in my little finger. Another centimetre or two and it could have cut off my fingers or slashed the arteries in my wrist. The cut bled heavily. I staunched the flow by wrapping my hand in my T-shirt and ran home. We lived too far from the hospital to have the cut stitched and the wound, though a nasty one, healed itself in time. To this day I have no feeling in that finger. Playing tennis, I had to alter my racquet grip to compensate for the injury, and my fingers, which forever after would stick stiffly out, were always catching on the left-hand side pocket of my shorts. In the end, Mum sewed up my pocket.

In many respects life today is better for children, but I reckon in some ways we had it very good. Surely playing games in the open air and swimming and fishing for barramundi in Moore Creek and the waterhole at Park Avenue Powerhouse is better than going cross-eyed in front of a computer game screen or living life vicariously watching TV.

We had our movies, but even a night at the flicks was an adventure for us in those long-ago country Queensland days. In Rockhampton there was an outdoor theatre . . . just a big canvas screen set up in a vacant lot with rows of folding chairs in front of it (though you could sit on the grass if you wanted) and a projector that shone its magical rays through hordes of bugs and summer moths up onto the canvas rectangle. Somehow, in my memory, it was always John Wayne rounding up the baddies on that screen, and rain, hail or moonlight we wouldn’t leave until the big fella had brought the last black-hatted desperado to justice. Even today, 60 years on and with the Duke long a resident of Boot Hill, I’m one of his biggest fans and will happily watch a western any day of the week. When I was touring on the pro circuit with Alex Olmedo, it bothered him that the Indians always got it in the neck in the westerns we watched at the movies or on the hotel room TV. So Alex, who was an Inca Indian from Peru whose nickname was ‘The Chief’, would wait until the Indians were winning, usually in the very early part of the movie, and then he’d up and leave before they inevitably bit the dust in the final reel. ‘I know we Indians will lose in the end, so I’m getting out of here while we’re still ahead,’ he’d say.

When Dad was looking for a place for us to live, one of his requirements was that the yard must have sufficient room for us to lay another homemade tennis court. At the Main Street Park Avenue house we were able to clear the scrub and Dad, Bob, Trev and I carted the soil and silt in his truck from the Fitzroy River and laid the court in the clearing. The good thing about silt, apart from being a good playing surface, is that when it dries and it’s windy the sand is blown off but when you water it again, more sand rises and holds it all together.

This time, we fitted out our home court for night play by stringing four 1500-watt light bulbs on an overhead wire down the centre of the court. Any of us kids who broke a bulb with a lob or smash was in for it. Those lights were dim, so consequently our eyes grew sharp trying to see the ball in the gloom and the ability I acquired to see the ball clearly and early stood me in good stead right through my career. The Lavers’ court was a magnet for local tennis players and was in constant use, as we played against each other and all-comers from kilometres around. One fellow who extended us was the young future champion Mal Anderson. Both my brothers were excellent players. Trevor was possibly the better, but Bob was no slouch and would grow up to be a tennis coach. One thing about Trev, though: when he played his emotions bubbled to the surface. If he was struggling in a match, everyone knew about it. He grumbled and griped and his shoulders sagged. I enjoyed playing against him when he was angry, because his mind wasn’t on the match. It occurred to me that it would benefit me to play without emotion – well, without emotion that others could see, anyway. Card players profited from having a poker face so opponents wouldn’t know how good or bad their hand was, and I figured a deadpan expression would work in tennis, too.

I was always happy when one of my brothers came home from school before the other, because then he’d be forced to have a hit-up with me. As soon as my other brother arrived, I’d be booted off the court so they could play each other. ‘Scram, kid,’ they’d say. One solution was to find Mum and she’d team with me to play Trevor and Bob in doubles. If she couldn’t, I’d occupy myself hitting against a wall, studying what a ball did on impact after I’d connected with a particular shot: would it shoot forward, spin back towards me or to the side, bounce high or drop dead? I also hit along a grass cricket pitch. One day Dad came home with the wood to build a back wall. My job was to screw the wooden panels onto a wooden frame. I did it wrong and assembled the panels vertically instead of horizontally, which meant that the panels warped. Happily, there was an up-side. When I hit a tennis ball against the wonky wall, the ball came back at me any which way and I had to be in position to return it. All of this helped my reflexes, anticipation and my footwork enormously.

I loved tennis. It seemed the natural game for me to play. I played in the rain and the wind, and under the blistering Queensland sun, which would soon cause my floppy sun hat to become saturated with sweat. To counter that, on very hot days I occasionally placed wet cabbage leaves inside my hat to keep my head wet and cool. Over the years, some media profiles of me have made out that I never left home without my hat filled with cabbage leaves. Nice story, but not true.

What I loved was the satisfaction of hitting the ball sweetly, the running to ram home a point or save one, the one-on-one combative nature of the game, facing up to an opponent and testing yourself against him. I think only boxing is as confrontational. There is a kinship between the two sports. You have two people facing each other in a contained space, probing for weakness and attacking it. Tennis players and boxers need footwork, timing and stamina.

Chapter 2Charlie and Hop

MUM AND DAD, WHO WERE NOT WEALTHY, DID SO MUCH for me. As well as the backyard court, I was never without a racquet and tennis balls, and when they wore out there would always be new ones. When I turned 11, they drove me without complaint to junior tournaments all over Queensland. We’d be up and out of bed at 2 or 3am, with Mum preparing sandwiches and thermoses of tea before Dad drove us from Rockhampton to Bundaberg, Brisbane or wherever else we had to go, hundreds of kilometres – and this was in the days when tough dirt tracks, not asphalt roads, linked the towns. Those road treks could take seven or eight hours, sometimes longer. Not that Dad always watched my every match. He liked to drop me off and say, ‘See you at 5,’ and in the time in between you’d find him in a congenial pub enjoying a rum and milk and reading his newspaper.

One of the best things they did for me was to introduce the remarkable tennis coach Charlie Hollis into my life. A regular player on our home court in Rockhampton, Charlie was a mate of my father’s and a nomadic bachelor who travelled around Australia, stopping here and there to coach children for a couple of years before moving on again. A tall and muscular, fastidiously attired man with carefully combed wavy brown hair, he was a fair player when young and had been an artillery instructor in World War II. He transferred his army modus operandus – explain, demonstrate, instruct, correct – to tennis coaching in the ’40s and ’50s. He bellowed at kids like the sergeant he had been, telling them when they were floundering that they were wasting their time and their parents’ money. He liked to bark at his pupils: ‘Why defend on the backhand when you can attack! Take the ball on the rise and use the speed your opponent supplies!’, ‘Up, change, punch!’, ‘You’re playing a smash. Do what the word says!’, ‘Attack! Attack! Attack!’

To Charlie, you were a mug or a champion, with nothing in between. He wouldn’t give you the time of day if he thought you had a couldn’t-care-less attitude. To him, the three traits every good tennis player had to have were heart, brains and a never-say-die fighting spirit. Whatever he did, it worked, and Charlie became a nationally renowned coach who contributed to the careers of Fred Stolle, Mal Anderson, Daphne Seeney, Roy Emerson, Wally Masur and Mark Edmondson, and yours truly. So influential was he that I have no problem saying that if Charlie’s and my paths hadn’t crossed I may never have become an elite tennis player. He could have made a swag of money charging for lessons, but looking after his finances was not Charlie’s strong suit and money seemed to slip through his fingers. He didn’t care, or didn’t seem to. He was a free spirit.

Dad, ambitious for his three sons and believing that all of us could be tennis world beaters – ‘One of you boys will play at Wimbledon one day,’ he’d say – persuaded Charlie, over a rum and milk, to coach my brothers. The first time Charlie laid eyes on me, I was 10 and he was putting Bob and Trevor through their paces. I’d crept out of bed to watch them and was peeping at them through the chicken-wire perimeter fence of our court when he spied me. Before I could run away, he said to Dad, ‘Aw, let the little bugger have a hit. I can see he’s keen as mustard.’ And there, under the 1500-watt bulbs, barefoot and in my pyjamas, Charlie and I had a knock, and I got that ball back over the net more times than I didn’t.

At first Charlie thought I was the least likely of the Laver brothers to succeed. I was, after all, a skinny runt, and a left-handed runt at that. Then, after a bit, he saw something in me and changed his mind. ‘Rod will be the best of the boys,’ he told Dad. ‘I’ll coach him for nothing, even if he is a midget in need of a good feed. He’s got the eye of a hawk. I believe we can make a champion out of him. And something else, Roy – Trevor and Bob, they’re like you. Quick-tempered. They blow up too fast. Rodney is more easygoing, a bit shy and self-effacing, like his mother. He’s too lackadaisical now, but I reckon if we can give him a killer instinct, it’ll be the perfect blend.’

Charlie Hollis taught me many things that he believed a budding tennis player had to know. One of the most important was not to grow complacent and compose eulogies to myself when I was ahead in a set, but to ruthlessly inflict the heaviest possible defeat on my opponent. Grind him into the grass, clay, concrete or whatever other surface we were playing on. In the beginning, I would do what I thought was the fair and decent thing and go easy on an opponent when I had him beat, and this often let him back into the match. Charlie stopped that trait quick-smart. ‘Go out there, Rodney, and win as quickly as possible. If you can beat him, 6–0, 6–0, do it. Destroy him. Never relax if you’re ahead. Never give him a sniff of getting back into the game.’

He also drummed into me that true champions never, ever give up – ‘Chase down every ball, Rodney, even if you haven’t a chance of getting to it.’ When I was being beaten was when I really had to be ruthless and mentally strong enough to claw my way back. If I lost a match without having busted my gut, he was scathing. ‘Why did you lose that match, Rodney? I’ll tell you! Because you quit halfway through it.’

Charlie taught me to remain positive rather than getting bogged down when I was behind in a match. Whenever he thought I hadn’t, he’d give me both barrels: ‘So what, you’re 1–4 down, don’t beat yourself up. If you break back everything will be fine. Put yourself in a position from where you can go ahead.’ Because Charlie instilled that optimistic attitude in me, throughout my whole career my concentration was better when I was behind because I learned to relish the challenge of working hard to regain the lead. Once in an Australian Open final against Neale Fraser I was down by two sets. It was match point against me but I did what Charlie had taught me to do: I hung in there, rode out the best that Neale could hurl at me, battled my way to recover and take the lead, and eventually won the match. I probably didn’t deserve to win it but I prevailed because I kept plugging away, telling myself, ‘He’s not going to beat me! And if he does beat me, I’ll make sure he does it the hard way.’ It can be a daunting prospect for any player to know that his opponent will never, ever quit. And when I did lose a match, and in my career I lost many, I never dwelled on that loss but consigned it to ancient history and thought only of how I’d win my next.

Charlie made sure I played on clay, concrete and grass courts (the only grass surface in our region was Mr and Mrs Shields’ court at their home in the gold-mining town of Mount Morgan, and Charlie wangled it so I got to play there occasionally) so I would learn how to alter my game to accommodate the idiosyncratic tricks and turns of each surface.

He was a stickler for correct form. By putting me through endless drills, he taught me to play every shot – the serve, forehand, backhand, volley, lob, slice and smash – as perfectly as I could. At the Rockhampton Association courts where he coached, he’d make all us kids stand in a straight line and hit imaginary balls. He’d be there facing us like a choreographer, performing all the strokes and then making us mimic exactly what he did, again and again, till we nailed the shot. He’d say, ‘Learn the stroke before you hit it. Groove it in. Watch the imaginary ball, now pretend to hit it. Then when you’re on the court in a real match it will come naturally to you.’ Good form was the talisman of a Charlie Hollis pupil. Whether the kid had the mental smarts and toughness was another matter. Such things are harder to coach.

Charlie also improved my serving by making me serve at a fence just two metres away. That way I didn’t have to waste precious time chasing balls. He also made me understand that if I was going to succeed I had to be fitter than my opponent – ‘Just think, Rodney, if you’re tired, the other bloke will be exhausted’ – and consequently he drove me to the point of collapse. It’s a good thing that I was happy to be driven hard. I thrived on sweat, tears and, occasionally, blood. You can have the greatest strokes in the world but you won’t be able to hit them properly if you’re buggered.

‘Just get the ball back over the net and let the other bloke make the mistakes,’ Charlie would say. More games were won by simply getting that ball back over the net than by fancy, risky shots that might win a match but also cost you one. By getting your serve in and hitting your volley deep, by relentlessly returning your opponent’s best shots, keeping the ball in play, you wear him down physically and mentally.

He encouraged me to put top spin on my forehand and backhand. ‘You’ll never win a big tournament unless you’ve perfected those shots.’ Top spin enabled me to hit my ground strokes hard but not too deep to a general area. Top spin carried the ball higher over the net. In rallies from the baseline I always put top spin on my forehand, dropping the racquet head below the level of the ball and coming over it with a snap of my wrist. He placed tin cans just inside the baseline and challenged me to hit them with my topspin drive. No session with Charlie ever ended before I hit 200 shots with top spin, with my coach yapping at me, ‘Rodney, get under the ball and hit over it! Under and over! Under and over!’ To improve my accuracy, he also marked various areas of the court and demanded that I hit them with my growing repertoire of shots.

Charlie drummed into me to come up with the unexpected in a match. Fool an opponent into thinking you were going to do A, then do B. To pull off this tactic I had to learn to disguise my shots. The wily Czech Jaroslav Drobny hit a marvellous example of a brilliantly disguised shot to beat Ken Rosewall in the Wimbledon final of 1954. Drobny, although an artist with a racquet, was never the fittest player, and he was leading two sets to one and 8–7 in the fourth but running out of steam, and the much fitter Rosewall was roaring back into the match. Ken got it into his head that Drobny would try to finish the match with a fierce serve and so stood at the baseline ready to return the inevitable cannonball, but instead Drobny dinked the softest serve to Ken’s backhand. Totally unprepared for such a shot, Ken raced forward but was off-balance and hit the ball into the net. Game, set and match to Drobny.

•

Charlie worked out that I could compensate for my small size by being super-fit and very strong. He told me I needed to do extra conditioning and strength work and he didn’t have to tell me twice. I ran long distances in the blazing Queensland heat, did endless push-ups and double knee jumps, and strengthened my left forearm and wrist by relentlessly squeezing squash balls.

After every coaching session, even when my body was aching, Charlie and I would play a couple of sets, and he wouldn’t go easy on me either. Charlie was demanding, and never satisfied. When I won my second Grand Slam in 1969, he cabled me from Queensland: ‘Congratulations on Grand Slam No.2. Now do it again.’

Mornings, Trevor, Bob and I would rise at 5 and ride our bikes to the hotel where Charlie lived in Rockhampton and I would let myself into his room and take the tennis balls from under his bed without waking him. Then my brothers and I would have a hit together on the Association courts, which were just down the road at the back of a petrol station, before Charlie showed up at 7 for our lesson, after which, hot and sweaty, we had to go to school. When the bell rang at 3.30 signalling the end of our last school lesson, we’d return to the Rocky courts for more coaching. Then we’d cycle home for dinner.

Often Charlie would join us at our dinner table, talking about past tennis champions, such as the great American Donald Budge who, in 1938, was the only men’s singles player ever to win a Grand Slam – that is, the championships of Australia, France, England and the United States in a single calendar year. Charlie had seen Budge win the Australian championships in ’38 and been deeply impressed by the American’s lethal backhand. The Australians Jack Crawford and Norman Brookes, Englishman Fred Perry, American Bill Tilden, the Frenchmen Henri Cochet and Jean Borotra . . . the legends’ names tripped off Charlie’s tongue. (Years later I played against Borotra in Paris and the experience brought Charlie’s history lesson to vivid Gallic life.) He also told me what he knew about the customs of London, Paris and New York, so I’d be prepared when – not if, but when – I played in big tournaments there. ‘You have to know how to act the part,’ he’d say. ‘You use your fork like a little savage. You must know how to eat when you go abroad. We want to be proud of you when you’re a champion. You’re representing the people of Rockhampton, Queensland and Australia.’ As well as good table manners, Charlie demanded that I stand straight and dress well, and thought nothing of disciplining me in front of Mum and Dad if he thought I deserved it. He said I should try to be like Gentleman Jack Crawford, the Australian champion of the 1930s, a fine player who fell agonisingly short of a Grand Slam, and was admired for his sportsmanship and generosity to opponents, his classy manners and, by wearing a long-sleeved white cotton shirt and long cotton slacks when he played, his sartorial elegance. ‘That’s how you’ve got to carry yourself,’ admonished Charlie, ‘like Gentleman Jack.’

In the four years that he coached me, from age 10 to 14, Charlie Hollis made me believe that if I continued to apply myself I could be a champion tennis player. At school I even wrote a highly imaginative essay about the day I was selected to play for Australia in the Davis Cup. Thanks to him, I could beat most boys in Queensland my age or a bit older, and was now regarded as the best of the Laver brothers. Bob begged to differ, and he fed me a dose of hard reality by beating me in the final of the North Queensland Junior Under-16 Championships.

My first official win in organised open competition – that is, playing against boys and men of all ages – was when I won the Port Curtis Open Tennis Championships at age 13. Many times opponents underestimated me because I was comparatively small, about 162 centimetres then (173 centimetres, or 5 foot 8 and a half inches, was as tall as I ever grew), and before they realised they’d misjudged me I had won the match. I was 12 when I was beaten by a much bigger boy, Mal Dixon, in the final of the Wide Bay Championships and he reckoned he couldn’t see me over the net. Mal’s a nice bloke and after I’d made my name in tennis he liked to boast, tongue firmly in cheek, ‘I once beat Rod Laver . . . once.’ The following year I beat Gilbert Beale of Bundaberg, a tall fellow well into his 20s, in the final of a B grade tournament in Gladstone. Gilbert took it well in his post-match speech: ‘I don’t mind losing to a slip of a kid, but having to kneel down to shake his hand was a bit rough.’

I was 13, too, when I won the Queensland under-14 singles championships. Before I left for the Milton courts in Brisbane, Charlie gave me a typically terse parting pep talk: ‘Rodney, don’t come back to Rockhampton without the state title.’ In the singles final I beat Barry Spence 6–2, 6–2, and John Sully and I won the doubles title.

My victories earned me selection in the Queensland schoolboys team to take on New South Wales schoolboys in Sydney in the Pizzey Cup interstate schoolboys tournament. On my first trip to the Harbour City, as much as competing in the tournament, I was excited to be billeted at Glebe, Sydney, home of my idol Lew Hoad, whom I’d cheered on when, as a strapping 16-year-old prodigy with matinee idol looks, he came to Rocky to play. I marvelled at Lew’s skill, power and laidback manner, which belied his ruthlessness on the court. I had adopted his practice of putting tape over the horizontal strings in his racquet to reinforce them, keep them from breaking and add power to his shot. I pictured myself hanging out with Lew, chatting about tennis into the night and having a hit-up together. Sadly, when I knocked on the Hoads’ front door, Mrs Hoad informed me that at that very moment, Lew was playing at Wimbledon. I would get to know Lew well in years to come. They say that often we are disappointed when we finally meet our idols. That was not the case for me with Lewis Alan Hoad.

In 1952, after I’d won the Queensland under-15 championships, Charlie and Dad took me to Brisbane to attend a Courier-Mail tennis coaching clinic conducted by Charlie’s old mate from his Melbourne days, the famous Harry Hopman. Hopman had been a member of the Australian Davis Cup team in the late 1920s and early ’30s, and he and his wife Nell had won the Australian mixed doubles title four times. After his playing days ended, he became the No.1 tennis coach in the world. When I met him he was five years into his 19-year tenure as Australia’s Davis Cup captain (under Hop’s stewardship Australia would win the Cup 16 times). Although Charlie told me on the long drive south from Rockhampton to Brisbane, ‘Now, hear every word Hoppy says and do exactly what he asks . . . but don’t listen to anyone except me!’ he enthused about Hop’s ability to get the best from young players and transform them into champions. He listed a few who had benefited from Hopman’s intense, some might say merciless, coaching: Frank Sedgman, Ken McGregor, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Rex Hartwig, Roy Emerson, Fred Stolle, Ashley Cooper. Not a bad bunch. Charlie had my attention, and so would Harry Hopman when I came under his wing.

A Time magazine journalist once called Hopman the most valuable man in Australian tennis, and described him as ‘a hard-nosed disciplinarian who demands monastic devotion and impeccable manners from his players’. Too true. He insisted on decorum, wanting Australia to be represented by, as he put it, ‘fine young men’. He laid down the law to the kids at his clinic: ‘You want to throw racquets on the ground and swear and not do what you’re told, then opportunities won’t go your way.’ He made it clear that it was his way or the highway. The Time article went on: ‘Hopman bosses an uncompromising talent-hunting organisation that spots promising youngsters and grooms them carefully for the big time. There is no nonsense about higher education: instead, players quit school at 14 or 15, take “employment” from some sporting goods firm, and spend every working minute on the courts.’ That journalist got it right. By the time I was 20 I was a battle-hardened player with six years’ experience and primed for the cauldrons of Wimbledon and Forest Hills. I suppose the flaw in Hop’s philosophy is that when a youngster devotes himself to tennis to the exclusion of all else and doesn’t make the grade, he is left high and dry.

Although Charlie had briefed Hop about me, assuring him I was one out of the box and had what it took to be a fine player, the great coach was unimpressed at first sight. Hop was big on personal appearance, and when he first laid eyes on me he didn’t think I looked the part, being, as I was, a short and skinny, freckle-faced, crooked-nosed, bow-legged blood nut, and painfully shy to boot. As had happened with Charlie Hollis, Hop revised his opinion when he saw me on the court. Being a protégé of Charlie’s and a state champion, I could obviously handle myself well in a match and I had an array of shots that was impressive for a young bloke. Yet the perfectionist Hopman still had a gripe about me. He thought I wasn’t strong enough, or speedy enough, and that is why, in the ironic Australian way, he christened me ‘The Rockhampton Rocket’. He once explained, ‘He was the Rocket – because he wasn’t. You know how those nicknames are. Rocket was one of the slowest kids in the class, but his speed picked up as he grew stronger. Rod was willing to work harder than the rest and it was soon apparent that he had more talent than any of our fine players.’ Like Hop said, I did get quicker, but the name stuck.

After I’d spent some time under his tutelage, Hop told Charlie he agreed with his assessment of me. ‘He is good.’ Praise indeed from this hardest of taskmasters, who, like Charlie, adopted a stern and strict façade to cover a soft and caring heart, and was, with his barking voice, impeccable dress and posture, and precisely parted hair Brylcreemed to within an inch of its life, not a little terrifying.

This coaching clinic in 1952 was also where I got my first taste of Harry’s two-on-one training drill, which I reckon was responsible in large part for Australia’s tennis success in the Hopman years. One of us would play at the net, and two others would stand back on the baseline, some metres apart. Hop would stand in the centre of the baseline and hit the balls to the bloke at the net, who then volleyed them hard and with accuracy to either of the baseline players. Sometimes there were two at the net and one on the baseline. Whatever the configuration, all three players had to be alert and ready to react and really run to get to the ball. Hop kept those balls rocketing and you’d better be ready. If you missed a volley, before you knew it he would thump another ball straight at you in the same spot. And another, and another . . . Five minutes and you were exhausted. There was no time to breathe. The idea wasn’t to hit the balls where the other guys couldn’t reach them but to put them where they had a chance of getting to them if they ran really fast. Play that game and you’re going to learn to do drop shots, hit angles, play top-spin lobs or ground strokes. Two-on-one conditioned me to adapt to pretty much anything that could possibly happen on a tennis court. It was unrelenting, and improved our accuracy, anticipation and stamina. None of us could last more than 10 minutes if we were doing two-on-ones properly, but I thrived on that gruelling drill, as did all those who let Hop take them to great places in our game.

The dashing Roy Emerson, just a year older than me but by then firmly established as one of Australia’s very best youngsters, was among the 24 kids chosen for the Courier-Mail clinic, and every chance I got I made sure I shook hands with Emmo, who became a fierce rival, great mate and is a neighbour today in Southern California where I live. Emmo was the fittest of us all. He thrived on Hop’s two-on-one drills and when he’d suggest we go for a jog he meant a 10-kilometre run, in soaring temperatures if possible. Roy could manage 100 double knee jumps when the best I could do was 50. He set the fitness standard and just by trying to keep up with him I became fitter. Remembering me from that time, Roy said: ‘I saw this tiny little 14-year-old kid. He came up to my waist, and he was wearing a big bush hat. I could barely believe the sight of him. Then he hit a few strokes, all those whippy sorts of things, and you could see all he needed was some size.’

I was told that over the 10 days of Hop’s coaching clinic, he noted my keenness to train hard and – sorry, Charlie – willingness to listen to him and put his teachings into practice. Hop thought I had a good all-round game with few weaknesses. He was happy enough with my stroke play and my fitness (he reiterated what Charlie had said, that if I was fitter than my opponent then I’d be well placed to win the fifth set of any match), my footwork, my intensity. However, he felt I needed to further hone my on-court killer instinct. I was still too nice to my opponents and not dispatching them quickly or ruthlessly enough. And he wanted to see me faster and more muscular. If I could do all that, he said, I’d be welcome at his coaching clinics in the future, and I had a remote chance of making it in the world of senior tennis.

Shortly after I returned to Rockhampton, I was laid low by yellow jaundice. I think I caught it from a schoolmate. I turned bright yellow and for six weeks I was away from school, too ill and weak to go near a tennis court, and because my liver was damaged my diet was black tea, bread, rice and steak with no fat. To recuperate and because my condition was contagious, I was sent to stay with Dad’s sister Fanny at her property near Wowan in central Queensland. The only compensation for being quarantined in Wowan was taking my .22 rifle and going out into the scrub to shoot targets or the kangaroos that were in plague proportions out there. When my liver repaired and my skin took on its previous hue, I returned to Rocky.