9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

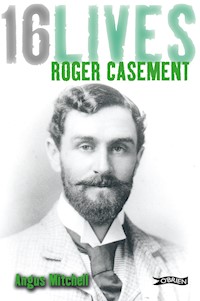

A fascinating examination of the extraordinary life of Roger Casement, executed as part of the 1916 rising, fighting the empire that had previously knighted him. Roger Casement was a British consul for two decades. However, his investigation into atrocities in the Congo led Casement to anti-Imperialist views. Ultimately, this led him to side with the Irish Republican movement, leading up to the 1916 rising. Arrested by the British for gun trafficking, he was incarcerated in the Tower of London and then placed in the dock at the Royal Courts of Justice in an internationally-publicised state trial for high treason. He was hanged in Pentonville prison on the 3 August—two years to the day after Britain's declaration of war in 1914.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Reviews

The 16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDEDonal Fallon

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGHShane Kenna

THOMAS CLARKEHelen Litton

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

ANGUS MITCHELL –AUTHOR OF16LIVES: ROGER CASMENT

Dr Angus Mitchell has published extensively on the life and legacy of Roger Casement and his significance to the history of human rights. He edited The Amazon Journal of Roger Casement (1997) and Sir Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness (2003). His work has appeared in the Field Day Review, Irish Economic and Social History and Dublin Review of Books. He has lectured at universities in Ireland, Britain, Brazil and the USA.He is on the editorial board of History Ireland.

LORCAN COLLINS – SERIES EDITOR

Lorcan Collins was born and raised in Dublin. A lifelong interest in Irish history led to the foundation of his hugely-popular 1916 Walking Tour in 1996. He co-authored The Easter Rising: A Guide to Dublin in 1916 (O’Brien Press, 2000) with Conor Kostick. His biography of James Connolly was published in the 16 Lives series in 2012. He is also a regular contributor to radio, television and historical journals. 16 Lives is Lorcan’s concept and he is co-editor of the series.

DR RUÁN O’DONNELL – SERIES EDITOR

Dr Ruán O’Donnell is a senior lecturer at the University of Limerick. A graduate of University College Dublin and the Australian National University, O’Donnell has published extensively on Irish Republicanism. Titles include Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803, The Impact of 1916 (editor), Special Category, The IRA in English prisons 1968–1978 and The O’Brien Pocket History of the Irish Famine. He is a director of the Irish Manuscript Commission and a frequent contributor to the national and international media on the subject of Irish revolutionary history.

DEDICATION

This biography is dedicated to the communities living near the waterways of the Congo and Amazon: their suffering is central to this story.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My greatest debt of thanks extends to Caoilfhionn Ní Bheacháin. Her constancy and belief have sustained me during the writing of this book and our beautiful daughter, Isla Maeve, is the result of our long friendship and deep love.

In Limerick: Brian Murphy OSB, Tom Toomey and Pattie Punch.

In Spain: Eduardo Riestra of Ediciones del Viento and Sonia Fernández Ordás, as well as Justin, Carmen and Beibhinn Harman, Sinéad Ryan, Ann Marie Murphy and the staff of the Irish embassy.

In Brazil: Laura PD de Izarra at the University of São Paulo, Mariana Bolfarine, Ambassador Frank Sheridan, Sharon Lennon, Tom Hennigan, Fernando Nogueira, Aurélio Michilis, Milton Hatoum, Elizabeth MacGregor, Filomena Madeiros, Liana de Camargo Leão, Beatriz Kopschitz X Bastos, Munira H Mutran, Juan Alvaro Echeverri (Colombia) and María Graciela Eliggi (Universidad Nacional de La Pampa, Argentina).

In Ireland: Jim Cronin and Rebecca Hussey. In Tralee: Seán Seosamh O Conchubhair and Dawn Uí Chonchubhair, and Donal J O’Sullivan, Padraig MacFhearghusa, Brian Caball, and Bryan O’Daly. In Dublin: Tommy Graham, Brigid, Malachy, Alexander and Nina. The staff of the National Library of Ireland, especially Colette O’Flaherty, Tom Desmond, Gerry Long, Gerard Lyne and the late and much lamented Maura Scannell. At the USAC summer school programme at NUI Galway: Mark Quigley, Méabh Ní Fhuartháin, Anne Corbett and Deaglán Ó Donghaile.

Thanks should also extend to Mairéad Wilson, Frank Callanan, Declan Kiberd, Deirdre McMahon, Catherine Morris, Paula Nolan, Luke Gibbons, Seamus Deane, Kevin Whelan, Tom Bartlett, Martin Mansergh, Stephen Rea, Tanya Kiang and Trish Lambe at the Gallery of Photography, Tadhg Foley and Maureen O’Connor, Maureen Murphy, Jordan Goodman, Mary Jane Smith, Amy Hauber, David P Kelly, Ronan Sheehan, Pierrot Ngadi of the Congolese Anti-Poverty Network, Dorothee and Michael Snoek, Moira Durdin Robertson, John O’Brennan, Pat Punch, Michael McCaughan, Leo Keohane, Eoin McMahon, Sinead McCoole, Brock Lagan, Radek Cerny, Stephen Powell and Inigo Batterham.

My editors at The O’Brien Press – Ide ní Laoghaire, Jonathan Rossney, Lorcan Collins and Ruan O’Donnell – applied the pressure when pressure was needed. I did my best!

Finally, I must acknowledge the unfaltering support of my wonderful mother, Susan Mitchell OBE, my brother Lorne, Susie, Yolanda, Torin, Rory and Oscar, my sister Colina, and my daughter Hazel: you are in my heart forever.

16LIVESTimeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville (O’Connell) Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eoin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAPS

South America

The Congo Free State (1903)

16LIVES- Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Introduction

The death of Roger Casement after a lengthy trial for treason closed the tragic events of the 1916 Easter Rising. In the eyes of the British authorities, Casement’s revolutionary turn was particularly loathsome because of his long and distinguished career as British consul in Africa and South America. For his service to the Crown, and his courage and integrity while carrying out investigations into crimes against humanity, he received a knighthood in 1911. During the course of his career he had corresponded with and influenced many of the leading statesmen of his age. For many years he operated inside the system and tried to bring about reform from within; when that failed, he emerged as its fiercest critic.

Casement’s extraordinary and somewhat enigmatic life has intrigued a succession of journalists, authors and historians. His meaning has never been easy to discern because, as both Foreign Office trouble-shooter and Irish revolutionary nationalist, he operated between two diametrically-opposed spaces of secrecy. Although he left behind an extensive and at times labyrinthine paper-trail, in which the paradoxes underlying his dual existence as government official and revolutionary can be perceived, the ‘truth’ about Roger Casement remains deeply contested. But truth and history are not always compatible.

One early chronicler of the War of Independence, Shaw Desmond, wrote of Casement: ‘Look well upon this man, because he carried in himself the whole story of Ireland. Learn the secret of this man and you have learnt the secret of Ireland.’1 What secret about both the man and Ireland did he mean? Was it what Éamon de Valera alluded to in 1934 when he commented: ‘No writer outside Ireland, however competent, who had not the closest contact with events in this country during the years preceding and following the Rising of 1916 could hope to do justice to the character and achievements of this great man … a further period of time must elapse before the full extent of Casement’s sacrifice can be understood and appreciated outside Ireland.’2

This biography attempts to unpick and explain the achievements of Casement by probing some of the interlinking secrets and conspiracies that have made him perplexing to historians. A century has elapsed since he openly turned from British official into Irish rebel leader, and we can now assess Casement in the light of much new evidence, including a box of material released as recently as 22 December 2012 by the National Library of Ireland. The veil of mystery has been lifted as far as it is ever likely to be, especially on the clandestine dimension of British state secrecy and Casement’s role as a consular representative of the Foreign Office.

In the last sixty years, much of the scholarship and journalism about Casement has been framed by the controversy over the authenticity of the Black Diaries. These shadowy documents, purportedly written by Casement and containing explicit evidence of homosexuality, were used during his trial by the British secret services as part of a coordinated campaign to discredit him and deter his allies from seeking a reprieve from the death sentence. After 1916, their very existence was denied until they were published in 1959 in Paris (at that time publication in Britain would have contravened the Official Secrets Act).

While there is a fascinating sexual dimension to Casement’s interpretation, there has been a reluctance to assess the Black Diaries within their proper historical context: either as valid sources for analysing his investigation of crimes against humanity, or as components in a bitter propaganda attempt to undermine his moral authority as a whistle-blower and to demean his intervention in the struggle for Irish independence. In the century since his death, an often violent war of words has been fought over these documents, with various political and academic reputations resting on the question of their authenticity. Casement’s wider concerns about the fate of humanity and his relevance to modern Ireland have been conveniently obscured by an enduring and ultimately pointless anxiety about his sexuality. My own scholarship preceding the publication of this book has argued that the Black Diaries are indeed forgeries and with this biography I build on that over-arching argument.

The ongoing debate over Casement’s meaning (the subject of the last chapter of this book) offers insight into why history matters and why the stakes involved in some aspects of historical representation are necessarily high. Casement’s life and death requires us to ask searching questions about the 1916 Rising and the last hundred years of Anglo-Irish relations. However, his legacy also obliges us to think about the ethics of international trade, slavery and his relevance to the modern discourse of human rights. More problematically, his flight to Germany in 1914 and the justification of his self-confessed treason sets us off down the thorny path of discussion on the causes of the First World War. Was Britain justified in declaring war in August 1914 (Casement did not think so) and what did Ireland’s sacrifice achieve? The historian Desmond Greaves alluded to these unsettling questions when he wrote:

So we must ask ourselves, what is it that makes the powers that be so determined that this mystery shall not be probed? Why are they so determined to discourage enquiry that would settle matters once and for all? Is it possible that we are all underestimating Casement’s importance and the part he played on the stage of history?3

Since this comment was written in 1975, at the height of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Casement has been the subject of a series of revisionist biographies that have placed undue emphasis on his sexuality, downplayed his relevance to his age and presented his contribution to the Easter Rising as peripheral and ultimately incoherent.4 Sixteen years later in 1991, when Ireland commemorated the seventy-fifth anniversary of the 1916 Rising, Casement’s name and meaning had been largely written out of the canon of modern Irish history. In 2012, the Irish novelist John Banville claimed Casement as ‘not only one of the greatest Irishmen who ever lived but also a considerable figure on the world stage’ and asked: ‘Why then is he largely forgotten, or ignored, in Ireland and elsewhere?’5 In a country where history and politics mix uneasily, the reasons are not hard to see.

Casement does not belong as wholly to Ireland as, say, the lives of Patrick Pearse or Thomas MacDonagh. His years in sub-Saharan Africa and Brazil are very much part of Britain’s imperial past. More than that, as this biography will argue, Casement represented a cosmopolitan nationalism and internationalism that cut against the grain of the image of the post-Treaty state. He had a definite sense of the future of Europe and Ireland’s place within the community of European nation states. While he may have turned decisively against the British Empire and returned to Ireland on the eve of the Rising to try and stop the rebellion, his reasons contained their own logic and integrity. In the narrating of 1916, Casement was himself betrayed, isolated and his intellectual contribution obscured.

His presiding sense of Irish nationalism was rooted in his love for the province of Ulster. It is symbolically revealing that the largest GAA stadium in Northern Ireland is Casement Park in West Belfast, and that Casement expressed a desire to be buried in Murlough Bay in Antrim and not Glasnevin Cemetery, where his bones currently reside. He claimed Ulster as the critical constituent in the making of a stable and prosperous Ireland, a view that has never suited the history of two nations of the last century. His historical meaning has therefore required sustained manipulation in the histories of modern Ireland and Great Britain. Understanding the management of his historical legacy is now central to appreciating his revolutionary turn, and the irreconcilable contradictions and differences encoded into his interpretation.

Angus Mitchell

Limerick, 2013

Abbreviations:

BLPES: British Library of Political and Economic Science

BL: British Library

CAB: Cabinet

CAE: Herbert Mackey (ed.), The Crime against Europe: Writings and Poems of Roger Casement (Dublin, 1958)

DT: Department of the Taoiseach

FO: Foreign Office

HO: Home Office

NAI: National Archives of Ireland

NLI: National Library of Ireland

NYPL: New York Public Library

PRONI: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

RAMT: Royal Africa Museum, Tervuren, Belgium

SRCHD: Angus Mitchell (ed.), Sir Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness: The 1911 Documents (Dublin, 2003)

TNA: The National Archive (UK); (FO: Foreign Office, HD: Historical Documents)

Notes

1 Shaw Desmond, The Drama of Sinn Fein (New York,1923), 165.

2 NAI, DT, 7804, E. de Valera to Julius Klein, 11 October 1934.

3 Feicreanach, ‘Roger Casement: The Man they had to Kill’, The Irish Democrat, August 1975.

4 Brian Inglis, Roger Casement (London, 1973); Benjamin Reid, The Many Lives of Roger Casement (New Haven, 1976), Roger Sawyer, The Flawed Hero (London, 1984), Séamas Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary (Dublin, 2008).

5New York Review of Books, 25 Oct 2012, LIX: 16, 35-37.

Chapter One • • • • • •

1864-1883

Nomadic Upbringing

The plaque commemorating his birth is still visible above the front door of Doyle’s Cottage in a quiet street of Sandycove, where Roger Casement entered the world on 1 September 1864. It is a simple house in a respectable neighbourhood of Dublin, renowned as the area of the city where the Martello tower in James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses is located. This coincidence is highly apposite, as Casement’s life has fascinating connections with the modernist epic of the 20th century; indeed, his name is referenced in the ‘Cyclops’ chapter:

Did you read that report by a man what’s this his name is?

—Casement, says the citizen. He’s an Irishman.

—Yes, that’s the man, says J.J.

On 16 June 1904, the date Ulysses made famous as Bloomsday, Casement’s name was circulating not merely through the pubs of Dublin but in conversations across the globe, from the heart of central Africa to the outposts of the British Empire in India, Australia and Canada. But despite being born in Dublin, Casement spent a comparatively small amount of time residing in his native city; like Stephen Dedalus, he became a citizen of the world. Nevertheless, Dublin would eventually become the site for the rebellion in which he played such a defining part and where his bones would finally come to rest.

Recent genealogical research has shown how the Casements moved from the Isle of Man to Antrim in the early eighteenth century. Different branches of the family held lands in both Wicklow and Antrim, and produced sons who generally went into either trade or the armed forces, and daughters who married into their own social class. Although Casement is inevitably categorised as ‘Anglo-Irish’, this is in some ways misleading. The extended Casement family might have had the airs and graces associated with the ascendancy class in terms of land, a big house and privilege, but for Roger Casement’s own family money was always scarce, and in references to his upbringing there is not the usual sense of either entitlement or advantage.

Roger’s father, also named Roger (1819-77), served in the British army in India with the Third Light Dragoons. In 1848 he sold his commission and returned to Europe to take part in the Louis Kossuth-led liberation of Hungary. Stories relate of how he held strong Fenian sympathies, identified with the Paris communards, and expressed beliefs in the principles of universal republicanism.1 He also dabbled in more esoteric interests, like Sikh mysticism; although, in line with Victorian parenting, he was quite a disciplinarian with his children. In 1855 he married Anne Jephson (1834-73), who was fifteen years his junior.

The background of Casement’s mother Anne is harder to establish with much certainty. In later life, Casement tried to research her connection to an old landed family, the Jephson-Norreys from Mallow in north Cork, but the information he uncovered was sketchy. It appears that she was baptised a Catholic, but quite possibly became an Anglican on marriage. Baptismal records show how she had Roger and his three elder siblings, Agnes, Charles and Tom, all secretly baptised as Catholics in Rhyl in north Wales. In Ireland, where religious difference is so accentuated, this unusual Protestant-Catholic duality is noteworthy, which might help to explain Casement’s early identification with the aspirations of the United Irishmen and his life-long desire to unite Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter.

The little that is known about the circumstances of the family derives from personal reminiscences written by his cousins Gertrude and Elizabeth and his sister Agnes, or ‘Nina’, as she was affectionately called. According to these, the family moved around the European continent, living briefly in France, Italy, London, the Channel Islands and Ireland, although it is not known why they moved so frequently. This state of nomadism would come to define Casement’s life, as he was destined never to settle in any place for any length of time. He lived in a constant state of motion: staying with friends and relatives, living briefly in rented accommodation, moving across the world by steamship and railways, or sleeping rough on his journeys into the African and South American interiors. But in the midst of all this endless travelling, Casement came to develop a particularly deep attachment to Ireland, and this love maintained him wherever he found himself.

The death of both parents by the time Roger was thirteen created a strong bond between him and his three siblings that would last for the rest of their lives. Roger’s relationship with his sister Nina was particularly close and in her memoir she lovingly described how from a very early age her little brother enjoyed the great outdoors. He learned to swim well and developed an exceptionally kind and empathetic nature, along with a hatred of injustice.2 She recalled, too, how he was an avid reader. Among his favourite books was James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, a tale of the demise of Native American culture during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), when France and Great Britain fought for control of North America.

The family home still directly associated with Casement is Magherintemple, a large and rather austere big house adjoining a lovingly-tended walled garden on the hills outside Ballycastle in County Antrim. This belonged to his uncle John, who took the orphaned Casement children in as his wards after the death of their parents. In his youth, Roger – or Roddie, as he was called by his immediate family – spent significant amounts of time at Magherintemple, and he returned there regularly to visit his relations throughout his life. To this day, the drafty rooms contain pieces of African furniture carved from tropical hardwoods, and a cabinet of ethnic curios that he presented like trophies to relations after returning from his African and Brazilian postings. But Magherintemple was not the only Antrim home where he was welcomed, and in several other ascendancy households, as well as the more humble abodes of local families, Roger was always made to feel at home.

He attended the Ballymena Diocesan School, where the principal, the Rev. Robert King, was one of the greatest Irish language scholars of the day, and Casement’s love for the Irish language appears to have been nurtured from a very young age in this environment. In notes written to the scholar and revolutionary Eoin MacNeill (1867-1945), he recalled:

My very old Master, the late Revd Robert King, of Ballymena, spoke and knew Irish well and often preached in Irish in his Protestant church of the Six Towns up in the Derry hills above Maghera and Magherafelt in the 1840s.3 … The first Irish I heard was in Ulster, in Co. Down in 1869, when I remember well often hearing the market people talk in it altho’ I was a tiny child then – also the boatmen from the Omeath Shore.4

By all accounts he was a diligent, quick-witted and intelligent pupil at school, and won several prizes for Classics. He enjoyed acting and singing, building up a repertoire of songs that included The Wearing of the Green and Silent O Moyle. According to Nina, he always stood firmly on the side of truth and integrity, while developing a strong sense of history. He read widely about the 1798 rebellion and how Presbyterian Antrim rose against English oppression. The nine Glens of Antrim, that stunning expanse of countryside within walking distance of Magherintemple, became the formative landscape for his youthful imagination. He took pleasure in linking the histories he studied to the surrounding environment. Nina remembered how he would walk around Donegore Hill, the site of a mass hanging of United Irishmen in 1798, and by connecting the landscape and local memory of sites of resistance to British rule in Ireland, he quickly cultivated a deep identification with the land and its people. ‘He learned much of the history of our country during those years. Long walks and visits to historic remains of antiquity, talking to the kindly Ulster folk who could tell many a tale of ’98 and the horrors perpetrated by the brutal soldiery of George III,’ Nina recalled.5

By his late teens he was writing poetry related to the history of Ulster, influenced by the melodies of Thomas Moore and the poetry of James Clarence Mangan and Florence McCarthy. Another inspiration was the late nineteenth century fashion for epic rhyme, while a familiarity with the Romantic tradition of Byron, Shelley, Keats and Tennyson was also evident. Metaphorically, this poetry was punctuated with the Celticist iconography and Gothic symbolism typical of the time: the silent harp, the mysterious ruined abbey, prophetic and spectral presences, and plenty of violence in the description of battles.6

O’Donoghue’s Daughter7

’Twas a calm Autumn evening, from hunting returning

I wearily spurred my poor steed thro’ the glade—

And on thro’ the glen past the Abbey lights burning,

Beneath its tall oaks and their far spreading shade—

And as nearer I drew to the lake I sent pealing

My bugle’s wild notes o’er the mist-shrouded water

When, oh! Like the voice of an Angel came stealing

From distance the song of O’Donoghue’s daughter.

Around 1880 Casement developed an interest in the politics of the Irish National Land League and the two principal figures involved in agitation for land redistribution and the protection of tenant farmers: the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, and the more radical MP, Michael Davitt. The politics of land became the determining issue of Casement’s life. ‘The land is at the bottom of all human progress and health of body and mind – and the land must be kept for the people,’ he wrote in 1911.8 This comment, made at the very height of his fame as a British government official, was shaped by his own observation of the Irish Land War and a belief that land should be utilised for the benefit of the nation and its citizenry and not exploited for the profits of the few. His intuitive analysis of the relationship between land, freedom, rights and national identity always informed his politics. In a speech he made about the Irish language during a tour of Antrim in 1905, he adopted geographical metaphors to explain his view of Irish nationality as inclusive, fluid and spiritually located:

[R]emember that a nation is a very complex thing – it never does consist, it never has consisted solely of one blood or of one simple race. It is like a river, which rises far off in the hills and has many sources, many converging streams before it becomes one great stream. But just as each river has its peculiar character, its own individual charm of clearness of water, strength of current, picturesqueness of scenery, or commercial importance in the highways of the world – so every nation has its own peculiar attributes, its prevailing characteristics, its subtle spiritual atmosphere – and these it must retain if it is to be itself.9

Casement’s upbringing coincided with the golden age of Victorian natural history and the belief that its study contributed to good health. His deep empathy for Ireland was developed as much by extensive walks and direct experience of the land and people as it was by reading newspapers and keeping abreast of events. The Victorians were obsessed with collecting, taxonomising and classifying the natural world and exotic cultures, and in this respect Casement was a product of his age. The Natural History Museum in Dublin contains a collection of butterflies he obtained when travelling through the Amazon. The anthropology collection in the National Museum of Ireland holds many artefacts – musical instruments, fabrics, basket weaving, fetishes and drums – which he gathered during his trips to Africa and South America. His official reports back to the Foreign Office contain references to issues like economic botany (the study of the commercial potential of plants), forestry, and environmental depletion. Much of his interest in the new sciences was learnt not only in the formal atmosphere of the classroom but as a naturally curious and energetic lad exploring the great outdoors. Later in life he would befriend and correspond with the most eminent Irish plant collector and forester of the age, Augustine Henry.

Many of the defining friendships of his life were made with people from the Glens of Antrim. During his late teens he spent much time with Ada MacNeill, a woman a few years older than him from a family near Cushendun. She too left a memoir of her formative years with Casement:

We were both great walkers and strode over the hills and up the Glens and we both discovered we could talk without ceasing about Ireland … Roger had the history of Ireland at his fingers’ ends.10

Over the next thirty years, Ada would become a tireless grassroots organiser for different nationalist causes in Ulster and a particularly active supporter of the Irish language movement. She remained a devoted friend of Casement’s. Her recollection of him, written shortly after his death, provides insight into less well-known aspects of Casement’s personality, including his spiritual and religious development. In his late teens, Casement was confirmed into the Anglican faith at the church of St Anne’s in the Liverpool suburb of Stanley while staying with relatives there. Although part of his faith merely conformed to the social expectations of the time, Casement was also moved by the deep religious fervour of late Victorian Britain and a more proselytising influence evident in Ulster since the Great Awakening of 1859, when evangelical preachers encouraged a religious enthusiasm that sparked widespread missionary endeavour. ‘He talked eloquently and earnestly against scoffing at religion,’ Ada remembered.

If by his late teens Ulster rather than Dublin had become his home, it would be Liverpool, the hub of Britain’s oceanic commercial power, that became the launch pad for his career. Known as the second city of the Empire, and long associated with both the slave trade and antislavery activism, Liverpool had deep connections to both West African trade and Ireland. Over the course of his life, Casement would build a lasting attachment to Liverpool, and much of the support he later garnered for his campaign to bring about Congo reform derived from his core of friends, fellow activists and philanthropists. In 1964, while canvassing during the general election as an MP for Liverpool, the future Prime Minister Harold Wilson invoked the memory of Casement during his campaign to win over the large Irish vote in his constituency with the promise that Casement’s body would be returned to Ireland in the event of a victory by the Labour Party.

Throughout his teenage years Liverpool served as a second home, largely due to his close contact with and many visits to his cousins, the Bannisters. His mother’s sister Grace had married Edward Bannister, then a prosperous trader with extensive interests in West Africa. The Bannisters provided Casement and his siblings with support and encouragement as they prepared to go out into the world. By all accounts, Edward Bannister was another important influence on Casement. In 1893, after eight years of sporadic service as Honorary Consul in Angola, Bannister was appointed Vice-Consul in Boma, a port town on the Congo river. His time there proved brief and controversial, as he personally stood up to the increasing levels of oppression by the Belgian authorities in the region, which contravened the humanitarian promises justifying European colonial activity in Africa. Casement’s early career in Africa was both facilitated and influenced by Bannister. The two shared a concern for the basic rights of the African, and Casement’s straight-forward and unaffected language, as well as his measured and methodical approach to the compilation of evidence, were skills apparently developed early in his relations with his uncle.

The Bannisters lived in the suburb of Anfield and Casement was given a room in the attic of their house. For the rest of his life he was particularly close to his two cousins Elizabeth and Gertrude, and carried out the longest and most intimate correspondence of his life with the latter, who stood devotedly by him until the bitter end and beyond. In her introduction to Some Poems of Roger Casement, published in 1918, Gertrude wrote of her cousin’s extraordinary level of empathy, evident since his childhood:

Even as a little boy he turned with horror and revulsion from cruelty of every description; he would tenderly nurse a wounded bird to life, and stop to pity an overloaded horse. This gentleness and tender-heartedness was one of his most marked characteristics; it led him to champion the cause of the Congo native and the Putumayo Indian, and to spend his slender means in later life in trying to relieve the wretched fever-stricken inhabitants in Connemara when typhus was raging amongst them, or to provide a mid-day meal for children in the Gaeltacht.11

For Casement, Liverpool became as much a place of departure as it was a place for family comfort and support. In 1880 he stood with his cousins on Waterloo Dock to bid farewell to his elder brothers Charlie and Tom as they set out for Australia to seek their fortunes. He would never see Charlie again. A few months later he found employment through family connections with a powerful Liverpool-based trading company, the Elder Dempster Shipping Company, one of several such companies shifting cargo throughout the Atlantic region and facilitating trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. For two years he worked in a clerical capacity, keeping the books and familiarising himself with accounting and trading practices. However, it soon became clear to his managers that his temperament did not suit the regular hours and monotonous work of an office clerk. After initial voyages to West Africa to test the water, Casement applied and obtained a job with the International African Association, the name of the organisation established by King Leopold II of Belgium to implement his colonial interests in the vast territories in central Africa to which he laid claim.

When Casement embarked from Liverpool in 1884 bound for a career in sub-Saharan Africa, no one could have imagined that twenty years later he would be both reviled and revered in the very city of his departure for launching a movement that is today upheld as precursory to that phenomenon of globalisation: the international non-governmental organisation.

Notes

1 Dónall Ó Luanaigh, ‘Roger Casement, senior, and the siege of Paris (1870)’, The Irish Sword, XV, 58, Summer 1982, 33-35.

2 Agnes Newman, ‘Life of Roger Casement: Martyr in Ireland’s Cause’, serialised in The Irish Press, Philadelphia, December 1919-March 1920.

3 NLI MS 10,880, Notes on Irish Language, RC to Eoin MacNeill.

4 Ibid.

5 NLI MS 9932.

6 Margaret O’Callaghan, ‘“With the Eyes of another race, of a people once hunted themselves”: Casement, Colonialism and a Remembered Past’, in Mary E. Daly (ed.), Roger Casement in Irish and World History (Dublin, 2005), 46-63.

7 CAE, poem dated 5 July 1883.

8 RC to ED Morel, 8 April 1911, SRCHD, 215.

9 NLI MS 13,082 (4), Lecture by Roger Casement on the Irish language

10 Ada MacNeill, Recollections of Roger Casement, Oliver McMullan Papers, Cushendall, Co. Antrim (n/d).

11 Gertrude Bannister (ed.), Some Poems of Roger Casement (Dublin, 1918), ix-x.

Chapter Two • • • • • •

1884-1898

African Roots

Roger Casement’s arrival in Africa coincided with the two events that did most to shape the continent during his lifetime: Britain’s unilateral occupation of Egypt in 1882 and the Berlin West Africa Conference (1884-85). The broad imperative determining British commitment to Africa was security of the Suez Canal; the safety of the routes to India in particular motivated political and economic strategy more than some master plan to carve out a new world.

After a period of intense exploration by European adventurers and missionaries, the natural resources and the enormous potential of the interior of Africa had been roughly measured. At the Berlin Conference, convened by the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, European diplomats tried to stabilise domestic rivalries by stimulating trade and turning their attention towards the colonial frontier of Africa. Following the signing of the General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885) a new relationship between Europe and Africa was initiated on European terms. This triggered a rapid division of the African sub-continent into spheres of influence as colonial powers scrambled for control of uncharted land. Exploration gave way to the signing of bilateral treaties with local chiefs and elders, the occupation of territorial claims through the agents of commerce and Christianity, and the imposition of structures of local administration. To pay for colonial government it was deemed necessary to develop the territories and make them economically viable. The dominant diplomatic player at the Berlin conference was the ambitious King Leopold II of Belgium, a man on a mission to build an empire. Through skilful negotiation he managed to persuade the other powers to recognise his rights to almost two million square miles of territory in central Africa.

For the years following the Berlin Conference, diplomats from Britain, France, Germany and Belgium were locked into a struggle for regional control. There were grand strategies at play: the French desired to connect their west African territories to the Nile; Britons dreamed of building a railway across Africa from Cape Town to Cairo; Germany wished to compete as an imperial power and join its colonies in south-west Africa (Namibia) to the Indian Ocean; while Portugal’s colonial settlements were in a state of stagnation and decline.

The language used to achieve these ends was one of humanity. The justification and moral legitimacy for what might now be understood as an act of ‘conquest’ was built on various discourses, which fused ideas of racial supremacy with the philanthropic concept of rights. The white man was bringing what he considered to be the values and advantages of western civilisation to the ‘savages’ of Africa. The rhetoric of empire was primarily inspired by a sense of mission, both social and religious, and a belief that power brought responsibilities. At Berlin, King Leopold preached philanthropy, promoting the idea of liberating Africans from slavery and implementing law and justice as building blocks towards a civilised future. But such idealistic notions needed to be underpinned by economic success. Ambitious young men were encouraged to see Africa as a land of opportunity and set forth to discover it for themselves. But whatever ideals might have driven them to leave their lives in the metropolitan centres of Europe, what they arrived in was a harsh new world driven by the trinity of imperialism, racism and militarism.

In 1884 in the town of Banana, at the delta mouth of the Congo river, Roger Casement offered his services to the International African Association ‘as a volunteer … to aid in what was then represented as a philanthropic international enterprise, having only humanitarian aims’.1 There he became one of the pioneer officers in what was soon to be known as the Congo Free State, that vast tract of land ruled by the absentee authority of King Leopold II.

The geographical enormity of the Congo defies straightforward description; it is equally difficult for the reader to imagine. Comprised of thousands of miles of inland waterways dissected by immense regions of unmapped, hardwood forests, it was quite the heart of the African continent. The reaches of the lower Congo region, extending from the nine-miles-wide river mouth to the settlement at Matadi, (a distance of around sixty kilometres by boat) was the area that was accessible to Atlantic steamship traffic and was initially colonised by European missionaries. Here Leopold claimed territorial rights to both sides of the river and two administrative settlements at Boma and Matadi expanded as colonial administration was extended. From Matadi, however, a series of cataracts and whitewater rapids cut off the lower or Bas-Congo from the upper Congo.

The upper Congo was in many ways another country: a vast basin of river systems and inland lakes hemmed in by tropical highlands and rainforest. Over centuries, communities had settled along the waterways, and boats were the most practical (and more often than not the only) form of transportation. But it was in the upper Congo where extensive, almost limitless resources in rubber, hardwoods, minerals and precious stones might be exploited. For the European, the problem remained one of access and logistics: how to transport the resources into their market economy as efficiently and discreetly as possible.

Abuses were inevitable. Until the building of the railway from Matadi to Léopoldville (Kinshasa), the base camp and hub for Belgian administration on the upper Congo, everything was fuelled by the blood and sweat of African forced labour. In 1898 a railway between Matadi and Léopoldville was opened. This engineering project was integral to Casement’s long involvement with the Congo. As goods moved in and out more freely, the Congo river became a commercial highway, but traditional settlements were decimated and communities ravaged. Commercial expansion necessitated ever-increasing levels of exploitation of the local people,

Casement’s initial duties for the International African Association appear to have been managing a local supply store and building up local trading networks. He appears in a photograph, dated 1886, beside several senior officers involved in pioneering work in the Congo.2 This included Sir Francis de Winton and Camille Janssen, the highest-ranking administrators on the Congo. Casement is visible at the back of the group, informally dressed compared to the others and wearing a straw hat instead of a pith helmet. The photograph acknowledges his early proximity to that exclusive administrative circle of white men who would ultimately wield huge influence in determining European policy in Africa. But while some of the men, such as Adolphe de Cuvelier, would go on to hold high office in Belgium, Casement would emerge twenty years later as the most energetic and outspoken witness and opponent to King Leopold II’s administration in the Congo Free State.

In 1886 and 1887, as an agent of the Sanford Exploring Expedition, led by the US diplomat and entrepreneur ‘General’ Henry Sanford, Casement helped to organise the transportation of a steamer, the Florida, overland beyond the cataracts to the navigable waters of the upper Congo river. This was followed by several months exploring the tributaries and villages of the upper Congo region and an extended journey through the rain-forested area that he would subsequently revisit in an official capacity in 1903.

This up-river voyage included a sixteen-day riverboat ride with the vicious Belgian Captain Guillaume van Kerckhoven, an officer in the Force Publique, the name of King Leopold’s military police force in the Congo. This officer is often cited as the inspiration for Joseph Conrad’s Mr Kurtz in his novel Heart of Darkness – the book that did more than any other to shape European views of Africa in the twentieth century. In 1887 Casement made his first personal complaint to the judicial authorities at Boma about brutality against the local people, only to be told bluntly that he had ‘no right of intervention’.3

The few surviving fragments of evidence relevant to Casement’s pioneering years in Africa indicate that his sense of youthful idealism was quite quickly tempered by disillusionment with what he witnessed. Perhaps this was the reason he chose to decline the offer made by the most heralded explorer of the age, Henry M Stanley, to join him on the Emin Pasha relief expedition, an opportunity that several of Casement’s closest friends opted for. This was the last exploration led by Stanley to cross central Africa with the somewhat spurious intention of relieving Emin Pasha, a German natural scientist who had been appointed governor of Equatoria (now part of the Sudan) and was being threatened by Mahdist forces. The expedition was a debacle and mushroomed into a vast controversy, with accusations of disloyalty, cannibalism, deceit and a series of conflicting eyewitness accounts by several of the officers involved.

One explorer who did join the venture was Casement’s Irish cousin, James Mountney-Jephson, whose diary contains the earliest published impression of Casement in Africa. It is an image of the conventional white explorer, adhering to the prevailing trends of colonial behaviour and, by this account, enjoying the African interior in some degree of style. The description contrasts distinctly with the ascetic existence that distinguished Casement in later life.

April 14 1887 … After I had been in camp about a couple of hours Casement of the Sanford Expedition came up & camped by me. We bathed & he gave me a very good dinner – he is travelling most comfortably & has a large tent & plenty of servants. It was delightful sitting down to a real dinner at a real table with a table cloth & dinner napkins & plenty to eat with Burgundy to drink & cocoa & cigarettes after dinner – & this in the middle of the wilds – it will be a long time before I pass such a pleasant evening again.4