Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

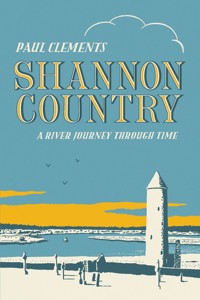

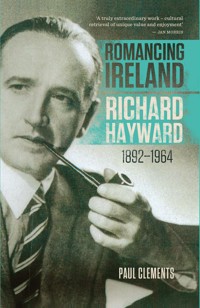

Richard Hayward was one of Ireland's best-loved cultural figures of the mid-twentieth century. A popular Irish travel writer, actor and singer, he led an intense and productive life, leaving behind a remarkable body of work through his writing and recordings. However, since his death in a car crash in 1964, the man who was a celebrated Irish household name has suffered neglect. Originally published to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his death, Romancing Ireland has now been reissued in an elegant paperback edition. Paul Clements brings to life the flamboyant personality, laced with hubris, of a largely forgotten figure who contributed a cosy and unthreatening narrative to the construction of an Irish cultural world. Romancing Ireland uncovers an extraordinary man with limitless energy and passionate perceptions, who captured a newly independent Ireland in all its changing hues.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 756

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Richard Hayward in his early thirties, painted by David Bond Walker and exhibited in 1926 at the Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Bookshops of Belfast

Irish Shores: A Journey Round the Rim of Ireland

Jan Morris: A Critical Study

The Height of Nonsense: The Ultimate Irish Road Trip

A Walk through Carrick-on-Shannon

Burren Country: Travels Through an Irish Limestone Landscape

Insight Guide Belfast

As editor

Jan Morris, Around the World in Eighty Years: A Festschrift Tribute

Legacy: A Collection of Personal Testimonies from People Affected by the Troubles in Northern Ireland

The Blue Sky Bends Over All: A Celebration ofTen Years of the Immrama Travel Writing Festival

Contributing editor

Fodor’s Guide Ireland

Insight Guide Ireland

To fellow travellers through Hayward’s landscape

Contents

By the same author

Dedication

Author’s note on names

List of abbreviations

Timeline

Epigraph

Introduction

Prelude

ONE: ‘Soaked in Irish songs and stories’ (1892–1910)

TWO: Sweet poetic aspirations (1911–1924)

THREE: ‘They lie who say I do not love this country!’ (1920–1937)

FOUR: Crusaders of the ether (1924–1950s)

FIVE: Master of his art (1920s, ’30s, ’40s)

SIX: Name in lights (1935–1939)

SEVEN: ‘As wonderful as Father O’Flynn’ (1936–1944)

EIGHT: ‘A stubborn divil’ (1942–1946)

NINE: Ulster versus Ireland: A ‘sugar-coating’ battle (1939–1946)

TEN: ‘We used to row like hell at times – as good friends do’ (1947–1949)

ELEVEN: ‘Talkative traveller’ (1950–1955)

TWELVE: Friendly invasion from the North (1952–1955)

THIRTEEN: Many-wayed man with an ‘eye for the main chance’ (1955–1959)

FOURTEEN: Munster literary swansong (1959–1964)

FIFTEEN: Tragedy strikes (1964)

SIXTEEN: Final parting

Postscript: Richard Hayward Assayed

The Ballad of Richard Hayward (1965): by Roy Dickson

Bibliography

Notes

Acknowledgments

Permissions and photo credits

Copyright

Author’s note on names

Throughout this book, the spelling of place names, mountains, lakes and other topographical features of the Irish countryside has been retained in the original way in which they were published in Richard Hayward’s writing.

List of abbreviations

ARPAir Raid Precautions

BBCBritish Broadcasting Corporation (formerly Company)

BFIBritish Film Institute

BGSBelfast Gramophone Society

BNFCBelfast Naturalists’ Field Club

BNLBelfast News Letter

BRTCBelfast Repertory Theatre Company

CCCorrib Country

CDBCongested Districts Board

CEMACommittee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts

DHDorothy Hayward

DLBDictionary of Literary Biography

DNBDictionary of National Biography

ENSAEntertainments National Service Association

GIGovernment Issue

HBHubert Butler

IFIIrish Film Institute

IKKIn the Kingdom of Kerry

ILTIrish Literary Theatre

INJIrish Naturalists’ Journal

IPUIn Praise of Ulster

IRAIrish Republican Army

IRJIrish Radio Journal

ITMAIrish Traditional Music Archive

JPJustice of the Peace

JRSAIJournal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland

KASKilkenny Archaeological Society

LCDLeinster and the City of Dublin

LHLLinen Hall Library

LOLLoyal Orange Lodge

MCCMunster and the City of Cork

MSLRMayo Sligo Leitrim & Roscommon

MWMaurice Walsh

MWPMaurice Walsh Papers

NAINational Archives of Ireland

n.d. no date (specified)

NLINational Library of Ireland

OBEOrder of the British Empire

OPWOffice of Public Works

OSOrdnance Survey

OUPOxford University Press

PENPoets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists and Novelists

PRIAProceedings of the Royal Irish Academy

PRONIPublic Record Office, Northern Ireland

QUBQueen’s University Belfast

RHRichard Hayward

RHARoyal Hibernian Academy

RHA, BCLRichard Hayward Archive, Belfast Central Library

RHA, UFTMRichard Hayward Archive, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum

RIARoyal Irish Academy

RICRoyal Irish Constabulary

Ricky H Ricky Hayward

RMSRoyal Mail Steamer

RSAIRoyal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland

RUARoyal Ulster Academy

RUCRoyal Ulster Constabulary

TCDTrinity College Dublin

TLSTimes Literary Supplement

UCDUniversity College Dublin

UFTMUlster Folk & Transport Museum

UIDAUlster Industries Development Association

UJAUlster Journal of Archaeology

ULUniversity of Limerick

ULTCUlster Literary Theatre Company

UTDAUlster Tourist Development Association

UTVUlster Television

UVFUlster Volunteer Force

WLYCWest Lancashire Yacht Club

Timeline

1892Born 24 October, Forest Road, Southport, Lancashire

1895Moves to Omeath, County Louth, then Larne, County Antrim

1896Attends Miss Cunningham’s School, Larne

1899Attends Carrickfergus Model Primary School

1901Boards at Larne Grammar School

1904Moves to Silverstream, Greenisland, County Antrim

191015 August death at sea of father Walter Scott Hayward

191131 May watches launch in Belfast ofRMSTitanic

Studies naval architecture

19159 July marries Elma Nelson, actress (two sons)

Starts first job at Cammell Laird shipyard, Liverpool

1917Returns to Belfast

Publishes first volume of poems

191820 November birth of first son Dion Nelson

1920Second volume of poems published; joins Ulster Theatre 18 December Hayward’sThe Jew’s Fiddle, drama jointly written with Abram Rish, staged at Gaiety Theatre, Dublin

192121 April joins Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club

1922Begins freelance sales agency work for Fox’s Glacier Mints

Love in Ulster and Other Poemspublished

1924Stages his playHuge Loveat Gaiety Theatre

Starts work as part-time commissioned agent for Needler’s Chocolates

1925PublishesUlster songs and ballads of the town and the countryBegins broadcasting radio plays inBBCBelfast with wife; starts singing career; forms Belfast Radio Players with Tyrone Guthrie

1927Gives series ofBBCradio talks on history of Irish towns; sings and presents stories onBBCBelfastChildren’s Corner13 December producesHip Hip Hooradio, first all-Ireland theatre relay transmitted from Belfast via Dublin to Cork

1929Records first two songs with Decca, ‘The Bonny Bunch of Roses’ and ‘The Ould Orange Flute’ Sets up Belfast Repertory Theatre Company with James Mageean; forms the Empire Players

1931November appears inThe Land of the Stranger, Abbey Theatre, Dublin

1932Sings in first indigenous Irish sound filmThe Voice of IrelandStages, and acts with Elma, in Thomas Carnduff play,Workers, at Abbey Theatre, and Empire Theatre, Belfast 19 December death of mother Louisa (‘Louie’) Eleanor Hayward

1935Sets up Irish International Film Agency Releases popular feature filmThe Luck of the Irish30 October birth of second son Richard Scott (known as Ricky)

1936Sings and acts in two films:The Early Bird(with Elma Hayward) andIrish and Proud of It(with Dinah Sheridan)Sails toUSon Cunard liner to promote Irish films Publishes novelSugarhouse Entry

1937Produces/acts inDevil’s Rock; starts film production company Sings for the first time with Delia Murphy

1938First travel bookIn Praise of Ulsterpublished, illustrations by J.H. Craig Releases documentaryIn the Footsteps of St Patrick

1940Where the River Shannon flowspublished, photographs by Louis Morrison, accompanied by travelogueWhere the Shannon Flows Down to the Sea

194115 April Hayward home in Belfast damaged in Luftwaffe blitz

1942Narrates and produces Stormont government filmSimple Silage

1943Publication ofThe Corrib Country, illustrated by J.H. Craig, with accompanying film Narrates and produces Irish government filmTomorrow’s Bread

1944TravelogueKingdom of Kerryreleased

1945Appointed honorary life member of the Carrick-on-Shannon branch of the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland

1946In the Kingdom of Kerrypublished with illustrations by Theo Gracey Releases documentaryBack Home in Ireland

1949PublishesLeinster and the City of Dublinwith illustrations by Raymond Piper (first book inThis is Irelandseries)

1950PublishesUlster and the City of Belfastwith illustrations by Piper

1951President Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club, leads field trip excursions all over Ireland, sets up folklore section with Brendan Adams and starts work compiling Ulster dialect dictionary 20 February first grandson Paul Semple Hayward born

1952Connacht and the City of Galwaypublished with Piper illustrationsPublication ofBelfast through the Ages, illustrations by Piper His arrangement ‘The Humour is on Me Now’ used inThe Quiet Man

1953Addresses twenty-fifth International Congress ofPEN, Belfast

1954The Story of the Irish Harppublished Involvement in Hubert Butler’s Kilkenny Debates

1955PublishesMayo Sligo Leitrim & Roscommon, illustrations by Piper

1956HisOrange and Bluechosen byUKmusic panel as one of the six outstanding recordings of the year

1957Border Foraypublished

1958Appears inTitanicfilmA Night to Remember

195917 March firstBBCNorthern IrelandTVappearance Appointed Doctor of Literature, Lafayette College, Pennsylvania 31 October sings on opening night of Ulster Television

1960Receives Insignia of Honorary Capataz of the San Patricio Bodega

196111 April Elma Hayward dies

196223 February remarries: Dorothy Elizabeth Gamble

1963Elected Honorary Life Associate of British Institute of Recorded Sound

196412 June appointedOBEJuly represents Ireland at International Congress ofPEN, Norway AugustMunster and the City of Corkpublished, illustrations by Piper 26 September birth of second grandson Richard Laurence13 October killed in car crash, Ballymena, County Antrim 4 November memorial service, St Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast

In the Kingdom of Kerry

The scholar in him shows us the Chi-Rho Crosses in the crumbled abbeys, the jester in him laughs at such phenomena as an unsinkable man; the zealot in him denounces the intrusion of sham villa on good landscape or the glazed tile on grey graveyard; the anchorite in him leads us up grass-grown roads and the imp and the acrobat in him takes us out on dizzy pinnacle of Skellig Michael and leaves us there with our vertigo for good company.

Extract from The Bell review by Bryan MacMahon of Richard Hayward’s Kerry book, 1946

Introduction

The Richard Hayward Archive is eccentric and eclectic, a haberdashery of an adrenaline-fuelled life. A vast array of topics reflect every facet of his work: travel, writing, singing, films, plays, broadcasting, lecturing, journalism and selling sweets wrapped up with a polar bear. Sifting through the detritus of his personal effects at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum near Belfast is a pleasurable if daunting task.

When I first explored it in 2009, the archive had not been catalogued and no one had been there before me. This is because Hayward’s second wife, Dorothy, was the gatekeeper of the flickering flame of his memory. For many years after his death in 1964 she guarded his estate with zeal, controlling queries from writers or researchers wishing to use or quote from his work. The sole legal beneficiary of his estate, including royalties, Dorothy had the right of veto over any use of his published, printed or recorded works and only she could approve of requests to quote from it. When she died in 2005, the museum took over ownership of the archive and copyright. In the words of the curator, Hayward was ‘an intellectual magpie’. Since he never threw anything away, more than half a century’s worth of correspondence and cuttings are crammed into boxes and plastic bags.

Hayward belonged to the age of letter-writing. Through his involvement with a range of organizations, he knew many people, which led to a broad sweep of friends, acquaintances and correspondents within the parallel worlds in which he worked. Hoards of letters from family and friends are crammed into padded envelopes or Jiffy bags. Others, from admirers of his books, films and songs, come with comments on his work.

In his own letters his character leaps out vividly, and although they are by no means the full picture of his personality, they provide an angled glance at his life and work.

No signposted route or index of contents guides me through the chaotic heaps of envelopes of hotel menus, guidebooks to Irish towns, cathedral, abbey and church histories, and publishers’ foxed book catalogues. Chaos has its advantages; serendipity triumphs to discover ‘Odds & Ends’; a brown box, labelled ‘Boys’ Shirts’, marked ‘Magic Tricks’; a bright orange crate overflows with documents and magazines. Poignantly, a long drawer holds ‘Correspondence after death’.

Cardboard boxes of film stills house hundreds of black-and-white photographs reflecting character roles from his big-screen appearances. Some crumpled photographs are held together with flaking Sellotape or staples. Promotional brochures for films and records deal with the collection of royalties. Handbills for his theatrical performances turn up in unlikely places alongside loose scraps of paper, backs of small envelopes, book dust jackets and postcards, all used to make notes.

To ensure he received articles written about him, Hayward employed the services of two cuttings agencies – one in Dublin and the other in London. The press clippings include interviews with him, appraisal and commentary on his work, and reviews and profiles of his latest ventures. Unsurprisingly for a man who spent much of his life driving the Irish roads, the map collection is extensive. Two boxes contain half-inch to the mile Ordnance Survey folding sheets of every county in Ireland. Some, in pristine condition, are mounted and linen-backed; others are torn and pen-marked. Bartholomew’s one-inch sheets of Ireland for Limerick and Shannon, Connemara and Sligo, and Donegal and Enniskillen are folded neatly to their concertina shape. Priced at three shillings, they are mounted on cloth with orographical colouring and roads. Hayward liked them for their detail, which included principal roads marked in red, good motoring roads in yellow, other serviceable roads, those not in general use, approved roads crossing the frontier, private roads as well as bridleways and footpaths. The Donegal and Enniskillen sheet contains pencil notes on his itinerary: ‘Bundoran: 9–10.30, Enniskillen 12 lunch, Castlecoole 3.30, Tea in Armagh or Dungannon.’

The highlight of the archive for me was coming across in two cardboard boxes the battered notebooks from his Irish travels with the artist Raymond Piper, one of five distinguished illustrators of Hayward. They provide an engaging insight into his modus operandi of recording information. Twenty ruled hardback books contain closely written notes alongside disjointed thoughts and sudden ideas that came into his head, which he quickly wrote down. These fragments are the repositories of his on-the-spot experience, meeting people, attending events, studying buildings and observing what was going on around him.

Reading the notebooks produces a sharp frisson of the immediacy of the personality and his time. He worked in a methodical and systematic way, writing in black, blue and green ink, sometimes in pencil, mostly in longhand. Occasionally he sketched a rough pen drawing, perhaps of a high cross or a ring fort, as aide-memoire (even though in his literary travels he was accompanied by a professional artist). For the most part, the notebooks do not contain personal information, but focus on place with moments of protest about the weather, which do not appear in the published books. Hayward took care with Irish place names, spelling them in capital letters and noting the exact wording of inscriptions on statues and gravestones. After returning home he frequently scored vertical or horizontal lines through the pages, crossing out sentences. He then chose the important information he required to begin the process of writing a draft. Selectivity was a key aspect since he made many notes that were discarded.

The archive, and in particular his notebooks, drew me into his orbit. I wandered the landscape with him, felt the heavy showers of rain and empathized when Piper tied an umbrella to a tree for shelter to draw a sketch in the Swiss Valley in Leitrim. Their immediacy offers the full sensory experience, the complete Haywardian vibes of seeing the initial nibble notes – the raw material – made in scrawling writing, his corrections, scratching-outs, scribbles, pencil doodles, underlinings, reflections and additions. Grace notes, bracketed asides and whimsical lines all bring him touchably close. Handling them, smelling the paper and ink, and wondering why he chose certain phrases feels like slipping out of linear time into the company of the man who wrote them seventy years ago. His excitement and curiosity is tangible.

The notebooks provide a portal into his thought processes and private world. Although they are a contrast with his published books and lack the polish of the finished product, they are important in understanding how he worked. As I read through them, the scale of the accretion of information he gathered becomes apparent; they are trophies of tens of thousands of miles of energetic travel representing a remarkable record. Nothing passed his gimlet eye and everything was grist to the Hayward writing mill. From my immersion in the archive one day a week for six months it is clear there are many Richard Haywards. Not only was he a writer, but he was also a singer, film star, stage actor, folklorist, dialect-collector, freelance journalist, broadcaster, entrepreneur and sweet salesman. I was in awe of his versatility and the sheer exhaustion of his expenditure of energy.

The highest form of travel for Hayward was the discursive quest, seeking out historical detail, bringing alive the people he met and recording the unusual. For the student of historical topography, and for a feel of what Ireland was like during the middle years of the twentieth century, his work is indispensable. This overdue book is part biography, part testimonial and part social history of an older simpler land. It is important to consider the impact on the cultural and literary geography of Ireland as well as Hayward’s historical and contemporary relevance. My purpose in writing it is to retrieve his legacy for a twenty-first-century readership and rekindle interest in his work. As well as reflecting the absorbing life of a many-wayed man with an omnivorous appetite for living, I have tried to present a balanced evaluation of his achievements.

When I got married in 1987, as a wedding present my wife gave me a special tooled-leather edition of In Praise of Ulster. Since then it has been in my top ten to-grab-in-case-of-fire list. This set me off reading his books and for three decades he has been part of my marital and mental furniture. I wanted to write about him but was unable to free up time from work and other preoccupations until 2008. The trigger came with the unofficial release of the marvellously disorganized archive in 2009. With the knowledge gleaned from the triangulation of letters, press cuttings and notebooks, I set about tracking down anyone still alive who could shed light on him, only to be met in most cases with a shrug or questioning blank: Richard Who-wood? In libraries, manuscript, archive, history and heritage centres the response varied from Robert Hayworth and Rupert Howard to Roger Wayward and Ritchie Hayweed ... ‘was he in the Fraternity of Man, or a drummer with Little Feat?’ a puzzled librarian wondered, her eyes filled with dim recollection; or, on another occasion, ‘Edward Hardware – did he write detective thrillers?’ I never met Richard Hayward but in some ways he has stalked me through his books and in his friendship with Raymond Piper. Now I plan to stalk him, spending time in another century, taking myself on a journey into the past.

Paul Clements

Belfast, 2014

Prelude

More than three million visitors each year tramp the streets of central Oxford, making tourism the city’s biggest industry. Few cast their eyes to the ground, ignoring the cobbled medieval streets and pavements splattered with bird droppings, cigarette butts and chewing gum. But unwittingly many of these tourists are standing on circular manhole covers or rectangular pavement lights, a long-established part of the street furniture. If they looked carefully they would see pig-iron manhole covers decorated with a five-petalled raised pattern and embossed capital lettering bearing the words:

HAYWARD BROTHERS PATENT – UNION STREET BOROUGH – LONDON – SELF-LOCKING

Some covers are barely readable. Others retain a pristine freshness, and with their circles and diamonds, chevrons and stars, trefoils and quatrefoils, are as clear as the day they were installed. In the world of eye-catching Oxford tourism, drain spotting comes firmly at the bottom of the must-see list. The humble manhole cover – for the operculist (lover of lids or covers) an aesthetic work of beautifully cast decorative symmetrical art – cannot compete with 100 amusing gargoyles of mermaids, musicians and monsters, or carved heads high up on college facades decorating entrance arches. Millions of visitors, as well as dons, undergraduates and locals have trodden these pavements ignorant of the industrial heritage underfoot. But what they have never stopped to ponder is that the company which fitted these utilitarian and durable covers, the Hayward Brothers, are the ancestors of Richard Hayward whose name too was cemented – not in the streetscape – but more glamorously in Ireland’s national culture.

Hayward Brothers pavement lights are widespread in central Dublin and can be seen along College Street, Dame Street, Suffolk Street and in this photograph at South Anne Street, off Grafton Street.

Hayward Brothers self-locking manhole cover outside Balliol College, Broad Street, Oxford. Hayward’s forebears ran a foundry in Borough in London and the covers can still be found in ubiquitous clusters in Oxford as well as other British and Irish cities.

His forebears ran a London foundry in Union Street, Borough. Since 1783 William and Edward Hayward had been trading as glaziers. In 1838 they bought an ironmongery business producing coal plates and later patented the addition of prisms with glazed glass that admitted light to the basement. To this day, these manhole covers and pavement lights – some with cracked glass – can be seen in parts of the capital as well as other towns and cities, including Dublin, Galway and Belfast. Nowhere are they found in such ubiquitous clusters as Oxford, a place where their presence commands so little attention. But as a tourism tag, ‘The city of dreaming drains’ lacks the allure of the dreaming spires. Those town drains and street gratings, like the life of Richard Hayward, have been woefully neglected. In a stark analogy with the man, they have become unnoticed, uncelebrated and invisible, trampled into history by the passing of the years.

ONE‘Soaked in Irish songs and stories’ (1892–1910)

The main street lined with open booths heavy-laden with yellow-man, hard nuts, cinnamon buds, and divers other tongue-tickling morsels. And old Mary Kirk nearby with her oranges and Larne Rock, and Ned Welch, and “Zig Zi Ah” Alec MacNichol, and ould Jimmie Morne. I don’t know Jimmie’s real name but he was always called Morne because he came from Magheramorne. Alec always affected a straw hat and a white waistcoat, and even as a child I used to envy his carefree life.

Richard Hayward,In Praise of Ulster, 1938

Although he took pride in his Irishness and had a great love for the country, Richard Hayward was born in Lancashire. On 24 October 1892, at 21 Forest Road, Southport, Harold Richard became the fifth of six surviving children. Within three years of his birth the family moved to Ireland where he grew up on the east coast of County Antrim. In later life he grappled with his birthplace trying to mask his English origins. His passports contain conflicting places and dates of birth. One states that he was born in Larne, County Antrim on 23 October 1893 and gives his profession as actor and singer, while a later passport in which he is described as an author, lists his place of birth as Southport and date of birth 24 October 1892.

His father, Walter Scott Hayward, the son of a London ironmonger who owned a foundry, was born on 17 April 1855 at 20 St James Walk, Clerkenwell. The company was called Hayward Brothers and was based in Union Street, Borough. They made manhole covers that are still visible in Irish, British and foreign cities bearing the name Hayward. During the late 1860s as a teenager, Scott Hayward spent time in deep-sea voyages before beginning a yachting career in 1871 with a small five-ton single-mast sailing boat, Rover. When he moved from London to the north of England he continued a lifelong interest in designing and sailing yachts. His first club was the Royal Temple in London, which he joined in 1871, racing his boat in club matches. His parents moved around different locations in England; firstly to Brighton on the south coast in 1873 where he joined the local sailing club, and then north in 1877 to Manchester. There he became a member of three clubs: the prestigious Royal Mersey Yacht Club, Cheshire Yacht Club, and New Brighton Sailing Club. Cruising and racing on the Mersey, as well as involvement in coastal regattas and local matches, took up a good deal of his time.

Conflicting passport details show that Hayward tried to disguise his English place of birth: the left-hand passport states that he was born in Southport on 24 October 1892 while the one on the right incorrectly lists his place of birth a year later as Larne, County Antrim on 23 October 1893.

With his handlebar moustache, Scott Hayward comes across as a confident dashing figure, perpetually busy, mixing business with his passion for sailing. After taking an examination in 1878 he was awarded a Board of Trade certificate as Master – a distinction achieved by few amateurs – and the following year chartered a small schooner,Resolute, making a trip to the coast of Morocco. On his return he was soon on the move again, settling in Southport where the attraction of the sea and opportunity to pursue his sailing skills held immense appeal. In 1880 he married at Ormskirk registry office Louisa Eleanor Ivy, the daughter of a local silk merchant, John Robson Ivy. Known as Louie, she was born on 24 January 1859 at Shoreditch in Middlesex and was four years younger than her husband.

Hayward’s father, Walter Scott Hayward, one of England’s leading yachtsmen, photographed in 1896 with his Royal Mersey Yacht Club cap and Liver Bird badge.

Hayward’s mother Louisa Ivy, known as Louie, was born in 1859 and was the daughter of a silk merchant.

The newly married couple lived in a redbrick house in an affluent area fifteen minutes’ walk east of the town centre and close to the main central station. The advent of the railway from Manchester in the late 1840s had brought the wealthy to Southport. Alongside them were the elegant mansions and well-appointed residences of prominent cotton industrialists, mill owners, jam manufacturers and a large Jewish business community. Forest Road, which ran through a tunnel of ash trees at one end, was a mix of terrace, semi-detached and detached houses with their own gardens. Many were built with the distinctive Accrington brick that gave a glazed shining effect. Surrounding roads, some lit at night with cast-iron lamps, reflected the Victorian arboreal fascination.

It was the era just before the arrival of the electric trams in Southport at the turn of the century. When baby Richard was born in 1892 horse-drawn trams and milk delivery carts plied the cobbled streets along with cyclists and the occasional landau carriage. As a baby he was taken in his pram to the Fairground or the Winter Gardens with its conservatories, promenade walkways, aquarium and roller-skating rink. He was too young to be aware of the newly installed and controversial ‘Aerial Flight’, which carried visitors high overhead in gondolas suspended from wires across from the fashionable Marine Lake. It was not to everyone’s taste. Some residents complained vehemently that it spoilt the vista from the promenade and it was removed in 1911.

Locals cared passionately about their views. From the long seafront promenade the mountains of Cumberland and the Wyresdale hills of Lancashire stretched away to the northwest while to the southwest from the esplanade, the Welsh hills, ending in Great Orme Head were visible in the distance. Lying between the estuaries of the Ribble and Mersey rivers, Southport, facing the Irish Sea, was less brash than Blackpool, its neighbour to the north. Since the 1860s the town had developed considerably as a genteel tourist resort. Day-trippers enjoyed the mild climate and bracing flat coastal walks along the beach or over the sand dunes as well as secluded sea bathing. Sand-yachting was also a popular feature of interest to holidaymakers. They dined in the tea rooms and coffee houses lining the fashionable boulevard of Lord Street where handsome glass-topped wrought-iron verandas stretched out in front of the shops. The resort was noted for traditional family seaside entertainment such as coconut shies while sweet stalls offered toffee, chocolate, boiled and health sweets, and the must-have labelled stick of Southport rock. By 1891 the population of the borough had risen to 41,406. It had become a desirable residential town and the ideal place in which to bring up a young family.

Some ancestral Hayward details are difficult to verify. But a letter to Dorothy Hayward from one of Richard’s brothers, Rex, after his death in 1964, claimed a fascinating family history, including a connection to Haywards Heath in Sussex – although this was never established:

Richard must have told you that our father was a famous swordsman. I have a photograph of him with his breast covered with medals. Both he and his wife were crack shots. Mother could hit a three penny piece with a revolver at 20 paces. My father used to cut an apple in half on my mother’s head.1

Whatever the potency of the Hayward name, his forebears appear to have been colourful characters, and for the children it was to be a peripatetic existence during the early years of their lives. The exact birth date of their first child and only surviving girl, Gladys Ivy, is unrecorded but was most likely in early 1883. Her first brother, Charles Hembry, was born on 19 February 1884 at Oakford in Devon, and was followed by another boy the next year: Basil Dean, born on 18 October 1885 at Oughtrington, Lymm, in Cheshire. Just over three years later, Reginald (known as Rex) Ivor Callender was born on 21 October 1888 at Altrincham in Cheshire. Harold Richard became the second-last child when Louie gave birth again on 24 October 1892, and Casson Boyd was born on 6 January 1899. Three other children had died in childhood, including twin girls who succumbed to an epidemic disease. The surviving family comprised one daughter and five sons.

Even with a large family to support, Scott Hayward threw himself com- pletely into the local sailing scene, emerging as the leading small yacht racer in the northwest of England. He helped form the Southport Corinthian Sailing Club, becoming the first vice-commodore, a position he held for three years. He later became captain for three years. At the start of 1899, theYachting Worldcarried a 500-word profile of him in its series ‘Yachting Celebrities’ along with a full plate photograph showing him wearing his Royal Mersey cap complete with its Liver Bird badge. The magazine outlined why he set up the club:

During 1894, seeing that something must be done if Southport wished to take a position as a yachting centre, Mr Hayward decided to form a yacht club, purely for the improvement of the sport and for the education of the younger men, this being barred to a very large extent by the difficulty which attended becoming a member of the existing clubs.²

Apart from his involvement with this club he was instrumental in forming the West Lancashire Yacht Club (WLYC) of which he was commodore for six years. On its formation, he was also appointed commodore of the Rhyl Yacht Club in north Wales. In 1887 he bought theNautilus, a four-tonner, which he raced for several seasons. Five years later, in 1892 – the year of Richard’s birth – he owned a dinghy to which he gave the fun nameThe Slut. Highly successful with it in sailing competitions, he won 165 prizes and seven annual championship cups. Boating honours and prizes continued to flow during his years in the northwest. He won 100 first prizes, forty-five second prizes and twenty third prizes. At different times in his sailing career, he owned forty yachts and ten motor boats collectively winning more than 2000 prizes. But Scott Hayward was renowned as much for his work designing boats as for his sailing prowess and organizational ability in forming new clubs. He was responsible for the design of a number of open boats and small yachts as well as fishing boats and motor yachts. One of his ventures attracted publicity in 1896 when he designed the largest motor yacht to have been launched on the Mersey. In total he designed more than fifty yachts and motor launches and his designs were adopted nationally and internationally.³

In the midst of all his water-based exploits, the family decided in 1895 to move to Ireland, choosing firstly Omeath in County Louth. An area with a scenic backdrop of the Cooley peninsula, and the Mourne Mountains on the other side of Carlingford Lough, it seemed to offer the ideal sailing potential sought by Scott Hayward. But they stayed only a short period, relocating to Larne on the coast of County Antrim, later settling fifteen miles south in a large house at Greenisland just north of Belfast. When he moved to Ireland, Hayward maintained his nautical interests, becoming a member of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club, the Royal North of Ireland Yacht Club and Donaghadee Sailing Club. He was honorary secretary of the Ireland branch of the British Motor Boat Club, the Motor Yacht Clubs of Ireland and Scotland, and the Yacht Racing Association.

Harold Richard Hayward aged four years and nine months in his fashionable sailor boy outfit with his toy yacht. He described his childhood in Larne as being ‘soaked in Irish songs and stories.’

Tour parties gather outside MacNeill’s Hotel in Larne for the start of a trip along the Antrim coast in the 1890s. This scene was familiar to Hayward as a child and one he later described in his first travel book In Praise of Ulster.

The Ireland in which the Haywards arrived with their young children was a country going through sweeping social change. Many organizations that would alter the cultural, political and working landscape were founded in this period. Radical ideas were taking root, new movements were formed and a host of practical groups emerged to help the lot of working people in what for many was a time of poverty and serious hardship. Workers throughout the country were united under the Irish Trades Union Congress banner; tenant farmers came together in a mass movement called the United Irish League, and the Irish Co-Operative Agricultural Movement and Pioneer Total Abstinence Association were founded. The Gaelic League and the Irish Literary Theatre (later the Abbey) were also building early foundations.

Much of this did not impinge directly on the life of people in Larne in the far northeast of the country. Historically the town was best known for the events surrounding the landing of Edward Bruce (brother to the Scottish hero, Robert) when he came to Ireland on a futile mission of conquest in 1315. Larne’s name means ‘district of Lahar’ (a legendary prince before the Christian era). Built straddling the River Inver, it was a meeting place of roads and people on the move. Of all County Antrim’s towns, it was more rambunctious than most. Neighbouring places such as Ballyclare, Ballymena and Antrim were humdrum market towns, but because of its situation as a port, Larne’s raffish air attracted visitors and a never-ending passing stream of travellers. Each day mail and passenger steamers linked the port to Stranraer in southwest Scotland, the short route across the North Channel, and many visitors passed through on their way to other parts of Ireland. Aside from this, steamers from the State Line, sailing around the coast between Glasgow and New York, called at Larne to embark passengers. A lively steamer trade also operated between Larne and Dublin, Derry, Glasgow, Liverpool and Ayr.

Throughout the 1890s the harbour was a scene of bustle reflecting the importance of the sea trade, bringing prosperity and employment. The Larne Shipbuilding Company was thriving while elsewhere jobs were created in engineering works and foundries as well as for smiths and millwrights. Towards the end of 1895 the British Aluminium Company opened a factory to convert locally mixed bauxite into pure alumina by chemical means giving employment to 100 men. The other main industries included flour milling, linen weaving and paper milling. But big money was being created around the new business of tourism and the train connected Larne to Belfast, helping social mobility. The place that Hayward knew was a small town of crowded streets. Writing many years later in his first travel book, he unlocked early memories to paint an evocative vignette of the time: ‘Religious fanatics, ballad singers, dancers, tramps, naturals, clowns, all in a motley crowd, no doubt attracted by the custom and largesse of Larne’s growing tourist traffic.’4

Handsome public buildings lined the streets. Six churches and three banks as well as the impressive town hall and the McGarel Building were familiar to Hayward as a child. Thatched houses were still prevalent. Three on the main street, five between the main street and circular road, and nineteen in the old town were all inhabited.5But the focal point for visitors was MacNeill’s Hotel on the main street. Henry MacNeill set up business in 1853 with a fleet of horse-drawn cars and wagonettes for excursions into the countryside. A pioneer of tourism in Larne, MacNeill capitalized on the new railways and ferries to Scotland, selling ‘package holidays’; his tour company brought in many people. Young Hayward met him when he was in his sixties and later drew an engaging pen portrait:

The architect and deviser of Larne’s bounty of swarming thousands from Lancashire and Yorkshire, dear old Henry MacNeill, old ‘Knock-’em-Down’ as he was known to everyone, what a character was he. I always used to connect him in my childish way with Buffalo Bill and I was always inordinately proud to be seen talking to him. Many a shilling he gave me, all unknown to my elders, and I should blush to say that I was unmannerly enough to accept his gifts. Human, all too human! And I’m so glad to be able to remember that I wasn’t a perfectly-behaved little prig! I can see now that Henry MacNeill was a man far in advance of his time, a genius whose circumstances led him to the tourist business.6

To accommodate the growth in trade MacNeill’s Hotel expanded in 1895 while another hotel, the Olderfleet, had already added a new wing the previous year. Larne’s population was increasing rapidly and in 1892 the town boundary had been extended. At the start of the decade, in 1891, the population stood at 4217, while by 1901 it had risen by just over a third to 6670. A progressive place, it was the first town in the north of Ireland to have public electric street lighting, which was installed in 1891. Larne had followed the example of Galway where in 1889 the electricity was generated by a dynamo replacing grinding machinery in an old water-driven flour mill – although in Larne’s case this was not a success and had to be replaced by steam-driven plant in 1892.7

At the turn of the century the narrow streets were filled with thirty grocers and the same number of drapers. Butchers, bookmakers and spirit retailers were all well represented in the business of the town. The rhythm of the agricultural year was important in the life of Larne. During the hurly-burly of the twice-yearly fairs on 31 July and 1 December, stalls and sellers attracted farmers and their families from outlying villages. The streets were also thronged with crowds attending hiring fairs that took place in May and November while a pig market was held on the fourth Wednesday of each month and a straw market each Thursday. The memory of those days stayed with him and in his later singing career Hayward recorded a popular ballad, ‘The Old Larne Fair’. George Baine’s bakery and confectionery shop, which also sold groceries and fancy goods, employed twenty bread servers and bakers, and was a popular haunt. Hayward recreates the atmosphere of the time, glancing back at a parade of some notables:

The main street lined with open booths heavy-laden with yellow-man, hard nuts, cinnamon buds, and divers other tongue-tickling morsels. And old Mary Kirk nearby with her oranges and Larne Rock, and Ned Welch, and ‘Zig Zi Ah’ Alec MacNichol, and ould Jimmie Morne. I don’t know Jimmie’s real name but he was always called Morne because he came from Magheramorne. Alec always affected a straw hat and a white waistcoat, and even as a child I used to envy his carefree life.8

Lester’s Café Royal Hotel, referred to as the Royal (English) Hotel, was bought by Ebenezer and Florence Drummer and later renamed Drummer’s Commercial Hotel; the couple were affectionately known to locals as ‘Eb and Flo’.9Another prominent figure in Larne that Hayward loved, and someone who brought his childhood to life, was the town bellman, Johnny Moore:

He was a character for whom I had great respect, for I always associated him with medieval romance and for some reason with Shakespeare’sLove’s Labour’s Lostwhich I was reading at school. I’m afraid the children of the town were not similarly impressed, for they used to torment poor Johnny with pointed remarks about his feet, which were not small. Indeed, he was always known to the irreverent as ‘Acres’. But I thought he was grand and ancient and traditional and all that, and I used to love the measured beat of his bell and the sound of his voice announcing an auction, some lost property, or information about the town water being turned off at seven o’clock each night on account of the drought. This always meant the filling of baths and buckets and basins and the use of far more water than would ever have been drawn had the supply been left unchecked.10

There is romanticism about his recollections of Larne, a place that stirred an interest in people that would stay with him all his life. A bright child, he was alert to the sights and sounds of what was going on around him. He lived in an area rich in history and archaeological ruins, and was becoming conscious of the past and the natural world. The Antrim coast road led north to quiet valleys, to the dramatic scenery of the glens and the tourist attraction of the Giant’s Causeway. When Thackeray came to the glens fifty years earlier he dubbed Glenarriff ‘Little Switzerland’.

All told, it was an exhilarating place. He became familiar with hidden coves and coastal beaches. On a clear day he could see across to the Scottish coastline. But nearer home it was the thin peninsula of Islandmagee linked to Larne by a ferry – a place with a dark past where early eighteenth-century witchcraft still remained part of local folklore – that took possession of his imagination. He wandered the country lanes and flower-filled meadows of this isolated part of east Antrim and was intrigued by the ‘Druid’s Altar’, a dolmen at Ballylumford. On one occasion when he was taken to the Gobbins cliff path – a stretch of coast on the southeast side made accessible by metal walkways and ladders, with caves and colourful basaltic cliffs – he was told the story of a religious massacre in 1642. A group of Presbyterians descended at night on Islandmagee murdering Catholic men, women and children by driving them over the edge of the Gobbins path into the sea. This was said to be a reprisal for the harsh deeds against Protestants in 1641. ‘I remember how, as a child, I used to shudder when I was shown the seaweed which was, so I was gravely informed, still dyed red with the blood of these poor people.’11

For all their myth-making, the Haywards were church-goers, business- people and solid citizens. The family placed importance on the value of a well-rounded education as a passport to a decent job. Scott Hayward was a Unionist and a member of the Church of Ireland, attending Jordanstown parish church. The young Richard became a member of the church and was confirmed by Bishop Frederick MacNeice, father of the poet Louis.

As a child, Hayward was known as Harold, a first name that stuck until his twenties when he switched to Richard. The family lived firstly in Beach Vista beside Larne harbour, later moving round the corner to Chelmsford Place, a quiet cul-de-sac off the main coast road at Sandy Bay. Their house was a distinguished three-storey terrace in an identical row of six. Each had small round-headed windows on the top floor, a one-storey return, and enclosed gardens surrounded by hedges. Views from the bay windows stretched across the water to Larne harbour while at Sandy Bay Point stood the 90-ft-high granite Chaine Memorial replica round tower erected in 1887–88. James Chaine had expanded the port of Larne in the 1870s and local legend says that he was buried upright in the tower.

At the age of seven, Hayward developed an interest in music, not just from the singers he heard on the streets of Larne, but also in the household. As a relatively prosperous family, they employed two servants; one, a teenaged girl from Ballybay in County Monaghan, taught him his first songs. From her he learnt Irish ballads that struck a special chord, leading to a lifetime’s interest in traditional songs and an abiding passion for the harp. The maid’s wide repertoire included ‘The Ould Leather Breeches’, ‘The Fair of Athy’, ‘Sweet Mary Acklin’ and ‘Wicked Murty Hynes’. Right through the day, from morning till late evening, the maid sang as she carried out her duties. Hayward later served up an account of this defining musical moment: ‘Some of these ballads I learnt and still sing, but others I have completely forgotten, for it was not for many years that I acquired the prudent habit of writing down what I heard.’12

Partly because of this, he describes his childhood in Larne as being ‘soaked in Irish songs and stories’. He does not name the maid but in the 1901 census she is listed as Lezzie Carroll, an eighteen-year-old Roman Catholic speaking Irish and English. The other servant was John Wilson, who was fifteen. A total of eleven people, ranging in age from two-year-old Basil to a fifty-two-year-old woman, Lily Leah Lucy, described as a ‘visitor’, were then living in Chelmsford Place. Hayward provides glimpses of his early schooldays. In the middle years of the 1890s, he attended Miss Cunningham’s school on main street and later Carrickfergus Model Primary School before transferring to the grammar school in Larne. ‘As if it were yesterday I can remember the voice of Miss Cunningham telling some unruly pupil that he was “the essence of disobedience”.’13

In the summer, his parents took him on trips with his brothers to different parts of Ireland. Given his father’s interest in boats it is no surprise that these were water-based holidays or coincided with yachting and sailing events. One was a boat journey along the River Erne from Cavan to Donegal, which ignited an interest in rivers and lakes. The young boy loved poring over maps of Ireland, discovering the names of mountains and lakes. He wrote later about being confused by the Upper and Lower Lakes of Lough Erne in County Fermanagh:

The Upper Lake is about ten miles long by three and a half miles wide, and lies to the south of Enniskillen. I remember as a schoolboy wondering why this should be the Upper Lake when on the map it is visually the Lower one, and I don’t think I have ever reconciled myself to this childish dilemma!14

With its quiet waterways and serene lakes, Fermanagh was a long way from life on the Antrim coast but became a favourite family holiday destination. In separate years around the turn of the century they spent a week at a time at the annual regatta in Enniskillen, staying in the Rossclare Hotel at Castle Archdale. The regatta was a huge event and Scott Hayward persuaded some English yacht-owners to take part in it. One year, in a spirit of adventure, he brought his children from Belfast Lough to Fermanagh by crossing the north of Ireland on an idyllic, if slow and lengthy journey, through inland navigation channels. En route, as well as appreciating the history and wildlife, they camped on river banks and small islands. For a boy, the excitement of once sleeping on a barge was a thrilling experience. ‘Those were the days, and I boasted about that night on a barge for many a month.’15

But it was a boat trip off the north Antrim coast, during which he came into contact with a celebrated name in the Irish cultural world that left the biggest impression on him. Hayward was just nine when, on a memorable journey in 1901 to Rathlin Island, he met Francis Joseph Bigger. A flamboyant historian and antiquarian, Bigger was an outspoken Ulster Protestant supporter of Irish nationalism. He was interested in reforging trade links between Rathlin and the Western Isles of Scotland, which had been extensive in the eighteenth century. The motor launch sailed on from Rathlin across the Sea of Moyle to Scotland although, to his chagrin, Hayward was not taken any farther and his adventure ended on the island itself. He was left with local people while the group went off to explore business possibilities. Longingly he looked across to the shadowy outline of the Mull of Kintyre, wishing he could have joined them. Nonetheless Rathlin, which he liked to refer to by its old name Raghery, cast a magic spell on him and he treasured the memory:

What dreams I had during the absence of the boat, and what a place was I left in for the nourishment of them. On the return of the voyagers I heard all about their triumphal entries into little Scottish harbours, and it was much later that I came to think of Francis Joseph Bigger’s immense flair for the historical background, which transmuted a small experiment in trade into a magnificent affair of merchant adventuring.16

Although nearly thirty years separated them, a friendship developed between the two and Bigger was to become an important influence on Hayward. His Presbyterian ancestors came from the lowlands of Scotland in the 1630s. They were part of a consortium of merchants who bought their own trading vessel,The Good Ship Unicorn of Belfast, one of the first trading ships ever owned by local merchants. By profession a solicitor, Bigger was also a writer, archaeologist and lover of Ireland who had many conversations with Hayward about the country and its past. He was elected a member of the Royal Irish Academy and was actively involved in the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club, serving as secretary and president. During his association with the Gaelic League he served on its executive committee, befriending Douglas Hyde, Eoin MacNeill and Roger Casement. He also revived theUlster Journal of Archaeology, becoming its editor. Although Bigger was well regarded by the scholars of his day, subsequent generations of archaeologists were less enthusiastic. They felt his approach and the purple prose of his writing were more akin to those of a romantic historian rather than a serious archaeologist. In some of Hayward’s writings, stylistic echoes of Bigger shine through and it is clear that he inhaled his perceptions.

The Irish landscape and coast, the play of light, the colours of the countryside and its waterways were imprinted on his mind from an early age. It was a leisurely era. The speed limit for the few cars on Ireland’s roads in 1902 was twelve mph. But in between the travels that brought him into contact with a range of people, he had to fit in his academic studies. The Hayward brothers were educated at Larne Grammar School. Founded in 1888, when it opened it had just nineteen pupils though the figure rose quickly to forty-five, including nine boarders. Lack of money prevented many parents in Larne from sending their boys to the school. At the start, the fees were a guinea per term for boys under twelve for English and Mathematics, rising to £2 6s.0d.for the whole course for boys over fourteen. The school also offered French, Latin, Greek, Euclid, algebra, drawing, natural philosophy and bookkeeping.

Set in its own grounds, Larne Grammar School prided itself not only on the quality of its education, but also on its location. Hayward boarded at the school during the early years of the twentieth century because his family had moved from Larne to live at Greenisland near Belfast.

At the time, Larne Grammar was for boys only. By the turn of the century, numbers had declined to just fourteen and some pupils did not attend with any regularity. Conditions were basic and the school lacked money to develop. Facilities for sport were poor. In Hayward’s time, in the early years of the twentieth century when he was a boarder, there were up to ten teachers for forty pupils. During those Edwardian days, bullying rituals had been established to initiate new pupils. Some boys were put into a barrel and rolled down a steep slope at the side of the rifle range, making them violently sick. On other occasions boys were thrown over a thick holly hedge in the school grounds by sixth-form pupils, then thrown back by boys of the fifth form. More than forty years after leaving school, with memories still vivid, Hayward recalled his first few days and a ceremony that he had been put through to test his resilience to torture; it was not a happy experience:

I can remember the terror of being initiated as a boarder at the Larne Grammar School. And little wonder, when that ceremony consisted of being grasped by several senior boys and of having one’s head held in a place never intended for such a purpose. How could I, how could anyone, fail to remember those horrible seconds of waiting and the eventual roar and rush of waters as one of the initiators pulled a chain! And how I strutted after it was all over and agreed with everyone that it was a necessary and glorious institution.17

The pranks did not leave any lasting wounds and Hayward appears to have been cheerful, submitting himself to the rules and conventions of boarding school life. It opened up a whole new theatre of people and ideas to him. A diligent student and literary-minded boy, he was quick on the uptake, with a retentive memory. His reading included Shakespeare’s poems and plays, which led to a love of drama. He realized the versatility of the English language and the power of expressive words in prose and poetry. This early interest in literature gave him a sense of creative possibility and he picked up on the turn of phrase, building stanzas and producing emphatic endings to pieces of writing. All this was cast into memory and proved fruitful in his later acting roles. A new headmaster, William Smyth Johnson, took over in 1901 determined to redress the school’s decline and promote education in the area. He brought a new lease of life and within a year, attendance more than doubled from twenty to forty-two. But he found it an uphill battle and left after just three years. When his replacement James MacQuillan took over in Hayward’s time in 1904, the school entered a new phase. MacQuillan’s tenure lasted thirty-three years. An influential headmaster and teacher, his love of English literature rubbed off on Hayward. He encouraged the boys to read more Shakespeare, nurturing their talents through honest criticism. ‘He was willing to have a go at teaching almost any subject, and could supervise an experiment in the lab., or conduct the school choir, or re-enact the Battle of Hastings with equal facility.’18

Hayward never lost affection for the school. Years later he attended annual dinners as well as prize-givings at which he donated to the library signed presentation copies of several of his books. The annual magazine,The Old Grammarian, shows that in 1956 and 1963 the school awarded a Richard Hayward Prize to pupils. He was also asked to judge a school writing competition.

Around 1904, when he was twelve, the family moved to live in Silverstream House in Greenisland overlooking Belfast Lough. Under the watchful eye of her father, his sister Gladys went on to become one of the few British women to gain recognition as a competitive helmswoman. She accompanied Scott on many of his trips across the Irish Sea to take part in a range of events. Initially she built up experience in a 10-ft dinghy and with her first boatSandpiperwon a first and two third prizes. Her father had taught her to sail in theWLYC, most likely on the Marine Lake in Southport and she crewed for him in this boat at all the club’s Seabird races during 1900.19

Gladys Hayward, Richard’s sister, being taught to sail in Belfast Lough by her father who designed motorboats and ran a marine engineering works. Gladys became one of the few British women to gain national recognition as competitive helms before 1914. Her husband was killed at the Somme in 1916.

Hayward family Edwardian studio portrait from 1906. Standing in the back row, from left to right, are Charles, Basil and Rex; seated, left to right are Richard (aged fourteen), their father Walter Scott, Gladys, mother Louise, and the youngest child Casson, aged seven.

Gladys was a member of the Royal North of Ireland Yacht Club, Liverpool Bay, Rhyl and Donaghadee Sailing Clubs. While never achieving the national renown of her father in the sailing world, she was nonetheless a respected yachtswoman. In 1907, despite its title, she merited an extensive biographical entry inBritish Yachts and Yachtsmen.In a male-dominated sport, Gladys sailed consistently to a high standard during the early years of the twentieth century, winning prizes at Southport and the Menai Straits regattas. At home she took part in the Belfast Lough and Silverstream regattas as well as competitions at Donaghadee. In 1906 she raced on the Clyde inCurlewwinning three firsts and one second; that same year she entered the Welsh regatta and drove and steered the 12-ft motor dinghyPop.20

Music swirled around his teenage years and his parents encouraged a love of it. In 1908 Hayward acquired his first phonograph, which worked in the same way as a turntable but with a large trumpet-like attachment instead of speakers. It was one of the latest gadgets but the only tune he had was ‘Stars and Stripes’ which, to the consternation of his brothers, he played non-stop for the first few days. ‘It did not appeal to my elders,’ he later wrote, ‘as much as it did to me after its hundredth performance. They found it rather monotonous, to put it mildly.’21As the months went by and his musical appreciation developed, he bought other cylinders and played them in the seclusion of the hayloft above the coach house. They were his solace and delight. He later became the proud owner of one of the new Edison Amberola phonographs, which he bought from Thomas Edens Osborne, a dealer he knew from visiting his shop in Donegall Square in Belfast. He described Osborne’s as a ‘welter of safes, filters, bicycles, soap powders, oils and plaster statuary, all of which he sold with equal enthusiasm.’22Aside from music, one other curious and noisy hobby that he indulged in during his boyhood was making fireworks. In the Edwardian era this was regarded as a fashionable activity for young boys; at Halloween he took delight in putting together rockets, bangers, crackers and Roman candles.23

Although he enjoyed the sea air while walking near his home, Hayward does not seem to have taken part in competitive team sports. There is no evidence that he ever played the traditional grammar-school sports of soccer, rugby or hockey. Gladys, Rex, Charles and Basil were all active members of Silverstream hockey team, which their father coached during the early 1900s. Between them, the Haywards made up nearly half the team but Richard preferred more sedentary activities. It was a conventional childhood with a secure and sheltered upbringing and while music played a large part, literature was prominent too. A bookish boy, he was an avid reader of literary classics. Culturally, the period was dominated by a generation that grew up with Thackeray, Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. But notions of freedom and escape played on his mind and he devoured boys’ adventure stories. His passion was stoked byRobinson Crusoe, which gave him a love of islands.24The teenage romantic showed evidence of wanderlust in his soul and dreamed of running off to a desert island. For the writer-to-be, it was a nourishing diet. His passing reference, envying Alec MacNichol’s ‘carefree life’ is a telling remark.