9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Tracey McDonald Publishers

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

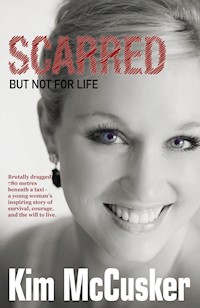

Brutally dragged 780 metres beneath a taxi, a young woman's inspiring story of survival, courage, and the will to live. 13 September 2011. The story would shock thousands and be remembered by many for years to come. It would be plastered all over the papers and continue to attract interest well after the shock factor of what happened had passed. Reports and articles would be written, and "facts", as given to reporters by some of those involved and willing to be interviewed, would be recounted and repeated in all forms of public media over the months and even years that followed. And although these versions would generate widespread outrage, none was entirely accurate. The stories were about me. I was there. I am Kim McCusker, "the girl who was dragged by a taxi". This, as I experienced it, is the true version of events.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

SCARRED

But Not For Life

KIM McCUSKER

First published by Tracey McDonald Publishers, 2016

Office: 5 Quelea Street, Fourways, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2191

www.traceymcdonaldpublishers.com

Copyright text © Kim McCusker, 2016

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-620-71102-9

e-ISBN (ePUB) 978-0-620-71103-6

e-ISBN (PDF) 978-0-620-71104-3

Text design and typesetting by Reneé Naudé

Cover design by Apple Pie Graphics

This book is dedicated to casualties, fighters and warriors of life, who have loved and lost, suffered and survived. Always remember – “believe you can and you’re halfway there” – Theodore Roosevelt.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Afterword

Chapter 1

I came into the world on 1 November 1985, the first daughter to my proud parents, Douglas and Patricia McCusker. They had chosen not to find out in advance whether I would be a boy or a girl and were pleasantly surprised when I arrived as a sister to my brother Gareth, who was two years old. They were less pleasantly surprised to discover that I had been born with my feet facing inwards – a condition known as clubfoot. As it would turn out, I was never destined to have a life without having to overcome at least a few personal challenges. And from the moment I breathed my first breath, the first of these was apparent.

Clubfoot is a common congenital birth defect. It results from abnormal development of the muscles, tendons and bones of the foetus and typically occurs in both feet 50 per cent of the time it occurs at all. From just fourteen days old and for the first ten months of my life, I was taken back and forth to an orthopaedic doctor where I had my feet put into plaster and manipulated every two weeks until they faced forward and the clubfoot was corrected. My dad, who was also born with this defect, was not as fortunate as I was. His feet were literally facing backwards when he was born. By the time he was six years old he had had 22 procedures done to correct the defect and, because of this, he only learnt to walk at six. Throughout his life he has had to deal with constant ankle pain, which has curbed his ability to participate in many normal activities. Fortunately, treatment for clubfoot is successful in 95 per cent of cases, restoring normal appearance and full functionality of the feet, and so I grew up with the only evidence of my challenging start in life being contained in what was told to me by my parents.

At ten months old, I was as normal as any other normal baby, with forward facing feet and all, but this was not to last for long, as my parents were soon to find out. In fact, I was never going to be normal when it came to my body and my health.

My mother was a nurse and early on she detected something unusual in my breathing. Partly based on instinct and partly as a result of her training, she felt a difference in my breathing when holding me as opposed to my brother Gareth’s breathing when she had held him at the same age. Repeated visits to the paediatrician revealed little. My mother also knew something was wrong because sometimes my lips and other parts of my tiny body would turn blue and I got tired quickly. My favourite and only word for a long while was “uppie”. I wanted constantly to be lifted up into my parents’ arms. Once I was crawling, even after I’d managed only a short distance, I tired easily. After having done anything that takes effort for a baby at that age to do, I would be tired and needed to be picked up and carried. By the time I was thirteen months old I had been to the paediatrician too many times for even the most paranoid of mothers (and paranoid was something my mother definitely wasn’t). On a day like any other, and while once again being examined by the paediatrician, for some reason my mother remembered something he had said to her when I was a newborn. Almost in passing, he’d observed that I had a slight heart murmur. When my mom’s recollection prompted her to mention this, the man turned as white as a sheet.

I had emergency open heart surgery at just over a year old. It turned out that I had been born with not one, but two holes in my heart: a ventricular septal defect (VSD) and an atrial septal defect (ASD).

The casual mentioning of the murmur resulted in a swift and thorough examination of my heart, which in turn resulted in the discovery of my congenital heart defect and the surgery that followed. I was in hospital for a long time but the defect was corrected successfully and I made a full recovery. I have no memory of any of the trauma I experienced as a baby – neither of the surgery nor the rehabilitation and visits to the doctor that followed. If not for the scar that starts on my upper chest and runs vertically down between my breasts and stops 15cm further down, as well as a few small scars from pipes and tubes having been put into me, I would know nothing about having had a near death experience and open heart surgery as a baby. In fact, my paediatric cardiologist has said that my scar is all the evidence there is. When I was better, life for me carried on. I was just another normal child.

I was blue-eyed, blonde haired, and relatively ordinary. Our family grew. First had come Gareth, then me, and later my brother Ian and sister Julia. We were blessed with wonderful parents and my childhood was a happy one. We were raised with good values and never wanted for anything. I was given every opportunity to excel in areas in which I showed ability, and excel I did. My mother was a devoted and hands-on parent and she ensured that we were stimulated and challenged to meet our developmental milestones. She spent hours teaching us things – the names of animals and the noises each animal made; we grasped colours, shapes and sizes early on. Educational toys were preferred in our home and as children our individual strengths were embraced and encouraged. If the alphabet was being taught to Gareth, it was taught to me too, despite being two years younger. If he was learning about numbers, so was I.

It was on one such occasion, when I was around four, that my mother noticed that I had grasped a principle Gareth hadn’t been able to yet, and that I had done so with greater ease than another four year old might. She took me along to the Schmerenbeck Centre for Gifted Children, where I was tested. It was discovered that I was indeed “gifted” and so began weekly sessions to encourage and enable me to reach my full potential in various capacities. Later on, when I was almost eight, I attended classes on a Friday afternoon at the Johannesburg Centre for Education. I tired of them in my last year of primary school, at the age when having a social life became the main focus. The “uncoolness” of having extra classes was exaggerated by my best friend Stacey thinking, and then telling everyone, that “gifted” meant “special needs”. She’d been spreading this about for years, believing I was “touched”. That convinced me to stop the classes – even though I was still debating with my parents whether or not I should.

Throughout my school years I achieved well academically. I received awards for outstanding academic achievement each year, among other accolades. I was a prefect in primary and high school and took part in swimming and athletics. I did ballet and played the piano outside of school and always achieved distinctions and awards in both. I was well liked by teachers, but not too much of a geek to be excluded or teased by my peers. I suppose you could say I was well balanced. I had lots of friends and generally got along well with most people.

One thing I learnt early on was that applying yourself and working hard got you the results you wanted. Failure was not something I was familiar with. If I wanted something, I knew it was largely up to me to achieve it, and I knew that I had to have the discipline necessary to get there. Being a hard worker and the discipline that came with it were things I carried forward into my adult life. I made things happen for myself instead of accepting hand-outs from others or taking short cuts. Good values instilled by my parents, a confidence in my knowledge of right and wrong and my striving to live life the right way, in combination with any talent and blessing I received, served me well. I knew that my decisions would largely determine my future and so I lived my life believing I was in control of my destiny. And my life, up until a certain point, did in fact turn out the way I wanted it to.

While still in matric, it was time to start thinking about where to go after school. I knew I enjoyed maths and science, but I wasn’t absolutely sure what I wanted to study. Some of my friends were also undecided as to what degree they should do and after talking and thinking about it, along with four of my friends from school I opted to do a BSc Financial Maths at Rand Afrikaans University (now the University of Johannesburg). It was a very difficult degree and I especially disliked mathematical statistics. I completed eighteen months of the BSc and after sitting through a mathematical statistics exam filing my nails, because I didn’t have a clue what was going on in about four questions of the paper, I decided to pack it in. Actually, I had been contemplating changing direction for a while because I was not enjoying the BSc. What I didn’t know yet was which direction that should be.

The prospect of studying law had come up in various conversations I had had over the past months. My father was an attorney and I started to take more notice of what he did in his law practice. Unexpectedly, law ended up as a good fit for me. I didn’t really want to be an attorney like my father, but we discussed other options of what one could do with a law degree. He pointed me in the direction of becoming an advocate, which appealed to me very much, and so I started down the path of attaining an LLB degree.

As I had stopped my BSc six months into my second year of study, I could not register for an LLB at RAU. Instead of waiting until the next curricular year, when I would be able to register, I chose to study through UNISA. I didn’t want to waste time waiting to get on with it, especially in light of the fact that I had “wasted” eighteen months studying for a degree I would not complete. I hoped to take whatever credits I could from UNISA back to RAU in the new year, where I planned to complete my studies. It turned out that I far preferred studying by correspondence and after transferring my credits for whatever subjects I could from RAU to UNISA, I completed my LLB through UNISA as quickly as I could, taking as many subjects each semester as the university would allow.

Distance learning gave me much more freedom than studying full-time and attending lectures, but it also required a lot more discipline. This part was never a problem for me, however, and I all but sailed through my degree, thoroughly enjoying my years as a student. While I was studying I also worked as an au pair. This meant I was earning my own money and didn’t need to go to my parents for everything – although this was by choice and never a requirement. My parents were very generous. I had a car and all living and entertainment expenses paid for, within reason. Their focus and expectation in return was that I do well, pass my exams and make something of my life. My father always said that the best gift you can give a child is the gift of education and I embraced the opportunities I had been given whole-heartedly.

Because of the freedom that came with studying through UNISA, I chose to finish the last semester of my degree in Ballito in KwaZulu-Natal, writing my final exams in Durban. My ex-boyfriend maintains that my move to Ballito was influenced by his decision to move to Durban, while I maintain that I did so because I could. I was never the type of girl to date many guys or even to date them on and off. I started dating my first serious boyfriend when I was in Grade 11. He was two years older than me and went to a different school. My group of friends (especially me and Paige) and his group of friends had been very close for many years before the two of us started dating. All in all we dated for over six years. We had a good relationship initially but we had our tumultuous periods too and we were never going to end up staying together always. We had our break-ups and our reconciliations as many young people in young relationships do. One of these break-ups happened while I was in matric. Having “moved on”, I began dating a guy from my school, who was also in my year. In hindsight, I always wished he had been my second serious boyfriend but another reconciliation made sure this was not to be.

My ex and I had been teenagers when we met and started dating. As happens more often than not, as the years went by and our relationship grew older, we both changed and eventually things ended. When he decided to move to Durban to get away from everything, we were still in contact, although we were not a couple. But his moving away enlightened me to the fact that moving was something I, too, could do. I began talking to my parents about it.

Although it might have looked like I moved to KwaZulu-Natal hot on the heels of my ex, it wasn’t the case at all. My parents had a holiday house in Ballito and I made the decision to go and live there for a year while I finished the last six months of my degree. Because I had changed degrees halfway through the year, I would now finish my LLB in June 2009. I had made the decision to go to the Bar and to train to become an advocate (provided I was accepted, of course) but the interview that would determine this would only occur in January 2010. And so I thought, what better way to spend my last six months of freedom after studying than on the beach? I knew that the “best days of my life” as a student were soon coming to an end. My plan was always to return to Johannesburg, but in the meantime a year in KZN seemed like an excellent idea.

And it was in KZN that I met my second “serious” boyfriend, which was going to prove challenging when the time came for me to move back to Johannesburg.

In 2010, as planned, I was back in Joburg. It was time for business. I had applied for pupillage, which is the training a potential advocate must complete and pass, and was accepted after being thoroughly interviewed by a panel consisting of junior advocates, senior advocates, and past and acting judges, among others. I did my pupillage under a very competent counsel, who was a friend of my father’s and who mentored me superbly. Pupillage requires a pupil to go through training in various fields of law and to complete a selection and multitude of legal practices. After close to a year of training under your master (mentor), as well as other advocates who specialise in different capacities, you are required to write the Bar exams. Only after passing these exams is one admitted to the Bar and allowed to practise as a member of the Bar Council. The exams that need to be completed are the following: Civil Procedure, Criminal Procedure, Ethics, Legal Writing, Magistrate’s Court Procedure and Motion Court Procedure. The first set are written exams but if a candidate fails, you are given a second chance at passing in the form of oral examinations, provided the result of the first written exam wasn’t below a certain percentage. I managed to pass my Bar exams without the requirement for an oral exam in any of the subjects. In my year at the Bar, amongst 68 attorneys who had chosen to become advocates, legal advisors and colleagues straight out of university, I was one of twelve who passed “straight”.

This didn’t make me feel superior or particularly proud. More than anything, what it made me feel was relieved! I certainly didn’t want to have to study some more or reveal my knowledge (or lack thereof) standing in front of a panel of seasoned advocates and judges. I had worked hard, yes. It had been hell sometimes. I had had countless weeks of lack of sleep. But I had done it – without having to prove myself orally as well. Courtrooms would come in due course and I looked forward to building a career as an advocate. Something my younger brother Ian once said to me still sits with me today. There was no doubt, he said, that I was “book smart” but “book smart” and “street smart” were two very different things. I, of course, had argued that I was both (obviously coming out on top during the discussion) but I knew very well that the people I had done pupillage would also, in time, probably turn out to be fierce adversaries. The thought scared me somewhat, but I had every intention of being able to give them a run for their money when we met in court one day. I looked forward to the challenges ahead.

I never imagined that all my dreams, all my goals and all my future plans could be ripped from my reach in a heartbeat.

I never imagined that one person’s decision could change another’s life so severely utterly, least of all mine. Until it happened to me.

Chapter 2

13 September 2011. The story would shock thousands and be remembered by many for years to come. It would be plastered all over the papers and continue to attract interest well after the shock factor of what happened had passed. Reports and articles would be written, and “facts”, as given to reporters by some of those involved and willing to be interviewed, would be recounted and repeated in all forms of public media over the months and even years that followed. And although these versions would generate widespread outrage, none was entirely accurate.

I was there. The stories were about me. I am “the girl who was dragged by a taxi”. This, as I experienced it, is the true version of events.

Early morning Joburg traffic is the bane of many people’s working lives and those heading off to work in the Lonehill area are generally used to having to exercise patience. You just have to accept that the morning rush is going to include long queues and stop-start traffic.

This particular Tuesday morning was no different. It was as ordinary as any other day. My fiancé Lourens and I were on our way to gym in Lourens’ Corsa bakkie at around 06h30. One busy intersection in Lonehill is a four-way stop and we were in the queue. We were quite relaxed, though, because we knew that the lane in which we were travelling opened up freely once you got through the four-way stop. Before the four-way stop cars sat bonnet to bumper, edging forward bit by bit as one car after the other crossed the intersection in turn.

Suddenly a taxi, as unruly as they come, approached the four-way stop at a reckless speed. The driver attempted to cut into the intersection from the right-turn only lane just as we were entering the intersection from the lane intended for road users to do just that. Misjudging the non-existent gap, the front left of the taxi collided with our bakkie’s back right as the driver tried to cut himself in and pull off his risky manoeuvre. Luckily, we weren’t travelling fast and the collision caused no serious damage to our car.

Nevertheless, as one does when an accident has happened, once we had cleared the intersection Lourens pulled over and got out. His intention was to have a look at the damage and then obtain the taxi driver’s details for the accident report he’d have to produce. This is normal procedure for possible insurance claims and the like. The taxi stopped a little further ahead than at the point of impact but the driver did not pull over to the side of the road and he did not get out. Instead he stopped right in the middle of the intersection, where now many cars were having to manoeuvre their way awkwardly around him. The driver disregarded them all and he stayed in his vehicle.

Lourens strode purposefully towards the taxi. I watched him in the bakkie’s rear view mirror and through the little window behind me. I saw him standing at the taxi driver’s window, talking and gesturing, obviously trying to persuade the man to co-operate. His body language showed that he was irritated but not aggressive. His words seemed to be having no effect at all. The taxi driver had his window opened only a few centimetres down and he simply stared straight ahead as Lourens repeatedly tried to get his attention. He wouldn’t open his window any further. It looked like he wasn’t even going to engage in the conversation. After watching for a few minutes and seeing that Lourens wasn’t getting anywhere, I made a decision that would change my life forever.

Thinking that perhaps the taxi driver might respond better to a woman and that maybe I could elicit at least some co-operation from him, I opened the passenger door of the bakkie and got out onto the road. I began walking towards the taxi, a distance of approximately fifteen metres, intending to join Lourens at the window. I could see the driver still looking straight ahead through his windscreen, completely ignoring Lourens. He was looking directly at me. As I approached the taxi I could see his glare fixated on me. To this day there is not a shadow of doubt in my mind that the taxi driver saw me approaching his vehicle from the moment I stepped out of the bakkie. When I was about a metre away from the taxi, the driver looked me straight in the eye and, with an expression I can only describe as one of hatred and malice distorting his features, he accelerated right into me. The taxi lunged forward, knocking me almost to the ground. While I urgently tried to right myself, I screamed, “No! No! You can’t go! I’m standing here!”

The man’s expression hardened, if that were even possible, and as I stood up, his gaze of pure hatred was fixed unwaveringly on me. And then, without a second’s hesitation, he went for me with absolute intention. I knew in that split second that this guy wanted me dead. He was not giving a second thought to committing a serious crime in broad daylight in full early morning commuter traffic. He was intent on delivering a message and I was the messenger.

As he hit me and I went down and under the taxi, which was now speeding up, my instinct kicked in. I told myself to keep my head and neck as far away from the road as I could under the circumstances. I knew I was in trouble the minute the driver had looked at me. I knew this was no accident. And now I knew I was in for a serious ride. What I did not know, until then, was that a person could so viciously and deliberately harm another human being, a complete stranger. Perhaps I was naïve and perhaps my fortunate life had shown me differently, but to experience such malice first hand was beyond shocking to me.

I didn’t experience the stereotypical “life flashing before my eyes” or being summoned “into the light” as many people apparently do in near-death experiences. I didn’t experience anything close to either of those. This isn’t to say I don’t believe some people have these experiences in near-death situations, but perhaps this only happens if you think you’re going to die. In my mind, in that moment, I only thought of two things and neither of them was about ending up dead. One – keep your head up. Two – this is bad, but this man is still human; he will stop soon. On thought one, I was “in control” and could make this happen to a certain extent. On thought two, I couldn’t have been more wrong.

As the taxi driver accelerated and with me already stuck and trapped under the vehicle, somehow – although I can’t tell you exactly how – I managed to hook my forearms into whichever parts I could and I pulled my head and chest towards them. I remember hanging on, literally, for dear life and thinking, no matter what happens, I’m not going to end up brain-damaged. Not even a little. Despite my resolve to keep my head up and off the road, it was impossible to do this successfully as the taxi continued to pick up speed. After the four-way stop I knew that the road opened up and cars routinely picked up speed there. The taxi did just that. With no obstruction in front of him, the driver accelerated – aggressively – and the taxi went faster and faster. Even if I had been able to hold myself up in spite of how fast the taxi was going, I would have required Herculean strength to do so over the distance he would travel.

Due to the position of our car relative to the taxi right after the bumper-bashing, as well as heavy traffic and no shoulder lane on this stretch of road, I had had to walk in a specific way to get to the taxi initially. Lourens had pulled over as close to the pavement as possible so as not to obstruct traffic, whereas the taxi had come to a stop just ahead of the point of collision with our car, in the middle of the busy intersection. The collision was so minor that neither vehicle had more than a little body damage and both were driveable. Stopping the taxi where the driver did, which was also full of passengers at the time, seemed as confrontational as it was arrogant. Obstructing traffic during peak hour was causing danger to everyone on the road. Because of our positions, I had had to walk diagonally towards the taxi from the passenger side of our car to get to the driver’s window as our car was metres ahead of his. I also had to do so very carefully because of the number of cars on the road. As a result, when he hit me, it was the taxi’s front driver’s side section that made contact with my body initially and this resulted in me being trapped beneath it at an angle. My head was centimetres away from the front driver’s side wheel but the angle was such that I could see the driver’s side of the taxi, even if only for a short while.

As the taxi sped off with me under it, Lourens screamed at the taxi driver to stop. When the driver ignored him, he sprinted after the taxi, which had already covered some distance. When he caught up with it, he punched right through the driver’s window. Not in anger. Not out of rage. He punched that window out of sheer terror in a desperate but futile attempt to get the man to stop so that Lourens could rescue me. He later told me that in the split second he had to think, he smashed the window so that he could try and pull the driver off the pedals. I saw him breaking the window and then diving through the window frame to get at the driver. He got hold of him around his torso and hung on for as long as he could while the taxi just went faster and faster and a passenger in the taxi whacked Lourens repeatedly with a knobkerrie. Eventually he was forced to let go and he went tumbling into the road. When he managed to scramble to his feet he stood watching his fiancée being dragged into the distance.

I was now in a real nightmare. I remember hearing screeching and shrieking but I have no idea whether this came from me, from passengers in the taxi or from other road users. I imagine the commotion I heard to be a combination of all three but I really only had my earlier thought one running through my mind (thought two was never going to occur). Two things I now knew for sure: one was that I was being dragged under this taxi for a considerable distance, and the second was that the driver was not going to stop voluntarily.

When he was finally forced to stop, he had dragged me for 780 metres. Seven hundred and eighty metres. And with each metre travelled my chance of surviving dwindled. At some point while being dragged, I must have lost consciousness because, while I do remember a lot, there’s a gap in my consciousness between being hit and dragged under the taxi and lying in the road once the taxi had finally stopped. Later I was told that many drivers of cars travelling in the opposite direction to the taxi had furiously tried to encourage the taxi to stop. Motorists pounded on their hooters and people – and there were many of them – shouted and gesticulated, loudly and fiercely. Even though the lane in which the taxi was going opened up after the intersection, traffic in the oncoming lane was still congested and cars had to slow to a crawl as they approached the intersection from the other side. However many cars fit one behind another for approximately 780 metres, they were all inching along and most of their drivers attempted to do something in an effort to end the horror that was unfolding. The taxi driver ignored every single one. Some drivers apparently even tried to obstruct the path of the taxi with their cars but nothing worked. One driver sped along in pursuit of the taxi, also to no avail. Across the road from where the taxi eventually stopped was an open park where a group of Fidelity security guards who patrolled the area were gathering for their morning parade before dispersing to their various posts. The taxi came speeding towards the park with me beneath it. When the guards realised what was happening, they joined together and formed a barrier in the road. The lie of the land right there was such that the taxi would have seen the guards in the road in time to slow down and avoid hurtling straight into them; it is also the reason the guards had time to act the way they did. I am told that once the taxi had slowed down sufficiently, the guards bombarded the vehicle, forcing the driver to pull up into a bus stop.

Lourens meanwhile, having failed to get the driver to stop, had run back to the bakkie and set off in pursuit. Shortly after the Fidelity guards had succeeded in bringing the taxi to a halt he caught up with it. In being dragged underneath the taxi, my body had moved from near the front, where it had hit me, towards the back of the taxi. When the vehicle finally came to a stop the back driver’s side wheel was on my pelvis. Lourens leapt out of the bakkie just as the guards were about to pull my body out. Lourens had experience as a fireman and paramedic and he shouted at them not to touch me. There was no knowing what the extent of my injuries might be but my fiancé knew enough to know the risk of possible paralysis should I be moved. So instead of me being pulled out from beneath it, the taxi had to be lifted off my body. With the help of many guards and with everyone’s adrenalin pumping hard, the taxi, still full of passengers, was lifted up and to the side to expose what was left of me.

It was at that point that I regained consciousness.

People told me that apparently the taxi driver was ripped out of the driver’s seat by some of the security guards and that he was roughed up a bit before being cuffed to the bus shelter. Most of his passengers got out of the taxi and filtered off in various directions, wanting nothing to do with what had just happened. Lourens paid no attention to the driver. From that moment on, his entire focus was on me. Some people have suggested that, possibly understandably, Lourens might well have torn into the taxi driver with full force right then because of what he had done, but the truth is that Lourens was certain I would soon be gone. He didn’t waste a precious second on anyone or anything else but me. Metro police officers arrived on the scene at some point and, or so I was told, assisted the taxi driver by giving him advice about his version of events, the version he should present at the police station. This version would imply the taxi driver’s innocence and would result in Lourens having criminal charges brought against him. It would cleverly manipulate the sequence in which the events occurred to suggest that the driver had fled as a result of being attacked by Lourens. In reality, the taxi driver had knocked me over and was already driving away, dragging me under his vehicle, when Lourens reacted by punching through his window in an attempt to get him to stop. The evidence would later prove this.

On the other side of the road, almost diagonally across from where I now lay on the tarmac, was the Lonehill Fire Department. Almost instantly, firemen were on the scene. My head and neck were securely stabilised and held in place by a fireman whose face would be all I could see for what felt like ages. I remember asking him to just let me lift my head to see what the drama was all about. I even tried to assure him a few times that I was fine. He, of course, could see how terribly injured I was, and he knew I was far from fine, so gently but firmly he would not allow me to move. I couldn’t see my broken and battered body, and I don’t remember feeling any pain at first either, so I really thought I was okay. Logically, I knew I would probably have some injuries but I somehow assumed they were minor. I didn’t know how far I had been dragged, nor did I have the least idea of the gravity of the situation.

At first I begged Lourens to just help me up and take me home. He wouldn’t. Then I told him I couldn’t see, because my glasses had fallen off somewhere on the road. I asked him to go and find them. He didn’t even try. He did not want to leave my side, not even for a minute – but he also knew there probably wouldn’t be very much left of those glasses anyway. I came up with a simple solution. I told him I had a second pair of glasses back at our house and suggested he quickly go and get them for me. It was futile asking and eventually I gave up. Convinced that these moments would be the last we would spend together, it was never going to happen. Lourens wanted to spend them right there, with me.

One of the firemen told me there was a lot of blood flowing from my peri-anal area and that he was going to have to place dressings down there. He did this repeatedly as dressing after dressing became saturated with blood. Still I felt no pain. Lourens told me again and again that everything would be okay. He encouraged me to hang on and to stay strong, constantly expressing his love for me. And as the minutes dragged on, with firemen tending to me and with Lourens glued to my side, I slowly realised I was not okay.

I searched Lourens’ eyes. “Is it bad?” I asked him.

“Yes,” he said. “It’s very bad.”

I told him to phone my mom, who is a nurse, which he did from a security guard’s phone. Uncharacteristically, neither Lourens nor I had taken our phones with us to gym this particular day. Lourens always made sure we had at least one phone with us at all times in case of an emergency but today for some reason we’d left our phones at home. He didn’t know my mom’s cell phone number by heart or have it written down anywhere. Somehow, calmly, I told him to gather himself; then I managed to give the number to him from memory. I told him to take instructions from my mother.

Lourens told my mom what had happened. He said I was in really bad shape and she advised him to have the ambulance take me to the nearest hospital – Life Fourways. I lay on the tar, bleeding from all over, waiting for what felt like forever before the ambulance arrived. During the half an hour it took for it to reach the scene, I became increasingly uncomfortable. I pleaded with whomever I could to get me to a hospital. When the ambulance finally arrived I was desperately impatient to get into it. The paramedics debated whether to put me on a drip while I was still lying on the road but I asked them not to. I have never liked needles. I know that sounds crazy, given what had just happened to me and the huge trauma my body had suffered, but I was scared I would feel a pin prick. At one point while the paramedics were moving me from the road onto the stretcher, an attempt to move my right leg caused me immediately to object due to severe pain, but besides that, extreme discomfort was all I experienced initially. The pain would come later. And when it came it would be fast and furious.

I wanted Lourens to come with me in the ambulance to the hospital but there wasn’t enough space for him and so I had to settle for him following us in the bakkie. I talked continually to the paramedics during the journey from the accident scene to the hospital, all the while becoming more and more uncomfortable. Time seemed to stand still. It was taking impossibly long to get to the hospital. I kept asking the paramedics what road we were on. Relief set in when they answered “Uranium Street” because I knew Life Fourways was not much further. On arrival, I was rushed into the emergency trauma unit where I still managed to tell the doctor on duty that I would be needing a plastic surgeon before being anaesthetised and before the real battle would begin.

The news of what had happened to me spread like wildfire. The girl being dragged by a taxi was headline news on every radio station. The coffee shop in the hospital’s foyer quickly filled and soon overflowed with concerned friends and family.

Meanwhile my life hung in the balance. All anyone could do was wait. Whether I would survive or not remained to be seen. While everyone sat together waiting for news from the doctors, my mom arrived at the hospital. She was still in her nurse’s uniform. Uninvited, and initially undetected, she walked straight into the operating theatre – to the extreme displeasure of the trauma doctor trying to save my life. “You’re a mother, not a nurse!” she yelled at her, but my mom firmly stood her ground. “On this occasion I’m a mother and a nurse,” she said.

This determination and my mother’s tenacity would soon become well known to all who were involved in caring for me and would play a considerable role in my survival and recovery. After she had seen what she needed to see, my mother returned to the crowd of people outside to update them as to how bad the situation was. It was severe. As a nursing sister who has to deal with death frequently, my mom has learnt that brutal honesty is crucial for patients and also for their support structure. She knows that giving false hope, despite the best intentions, is destructive, and so, as doctors tried to stabilise me, she told friends and family the truth – that it was touch and go. She told them I was still alive, but barely. She sent my brothers, sister, father and Lourens into the operating theatre to see me, possibly for the last time, and warned everyone that the next few hours would be harrowing. Hour after agonising hour crept by. After almost seven hours the doctors succeeded in stabilising me, and everyone breathed a small sigh of relief. At least I was alive.

I had suffered huge blood loss. I was intubated, ventilated and fully sedated. I would remain heavily sedated for several days. I required more than eight units of blood on arrival at hospital and had all sorts of pipes and tubes feeding all sorts of medication into my body. Only after I was stable could the extent of my injuries be assessed. Scans and other procedures were performed and they revealed the horror of what my body had endured. A full CT scan showed that I had an extensive extra-cranial soft tissue injury, partial compression fractures of vertebrae T11, T12, L1, L2 and L5 (T and L referring to thoracic and lumbar; the numbers indicating the position of the vertebrae fractured), a chip fracture of vertebra L5 and a subtle injury to vertebra T10, a fractured left baby finger, a cracked sixth rib, a crack in my pelvis, and fractures to both knees. And those were just the bone injuries. Soft tissue, skin and muscle almost all over my body had borne the bulk of the attack with devastating consequences. My wounds would be classified as full thickness and fourth degree burns and treated as such to any possible level of repair. A full thickness burn involves the destruction of the entire epidermis and most of the dermis and requires excision and skin grafting to heal. Fourth degree burns are full thickness burns that extend into muscle and bone. Because I had been dragged along tar, at speed, for almost 800 metres with little more than a thin layer of clothing to protect me, I lost a huge amount of skin and tissue. Fifty-eight per cent of my entire body surface area was either gone or severely damaged, exposing nerves, tissue, bone and muscle in multiple areas.

Despite being stable, the discovery and confirmation of all my injuries supported the improbability of me surviving the night, let alone the ordeal. My friends and family were discouraged from becoming too hopeful. Even though the chances that I would survive were slim, the doctors nevertheless needed to contemplate what steps should be taken next. And so a while later I was taken back into theatre for my injuries to be attended to. Over hours my multiple wounds were debrided, sutured and dressed. This included my buttocks, back, arms, elbows, left hand, right hand, fingers, scalp, left ear, left toe, left heel, the top of my left foot, right lower leg, and face. I also had an external fixator fitted to my right leg.

Debridement is the removal of foreign matter and dead, damaged or infected tissue from a wound. Surgical debridement and the use of a high-pressure hose and antibacterial scrub were the methods used to remove dead and dying tissue, as well as tar, material, dirt and other foreign matter from the wounds covering my body. This initial procedure took about seven hours. It was a process that would be repeated multiple times.

External fixation is a surgical process used to stabilise bone at a distance from the injury focus, which at this critical stage was the soft tissue damage. Pins are inserted through the skin and into the relevant bones and held in place by an external frame. After seven and a half long hours, the first of many surgical procedures to follow had been completed. Miraculously, I was still alive and stable, even though it hadn’t been smooth sailing entirely while in theatre. I came out of theatre at around 21h30 and while some family and friends had stayed to support my parents, my siblings and Lourens, most had left the hospital by then after a very long and draining day. I was taken into an isolation unit in ICU in a critical but stable condition.