7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

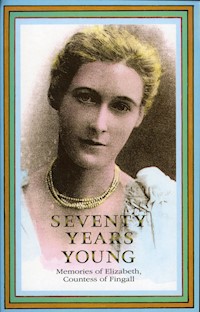

Seventy Years Young is one of the great Anglo-Irish memoirs. Originally published in 1937, it now appears for the first time in paperback, with an introduction by Trevor West. It tells the remarkable story of Daisy Fingall (nee Burke) of County Galway, who in 1883, aged seventeen, married the 11th Earl of Fingall of Killeen Castle, County Meath. Daisy's vitality possessed and transformed that twilit world of Catholic Ascendancy Ireland, a world in transition – from viceregal, country-house Ireland of Dublin drawing-rooms and Meath hunting-fields, now as remote as pre-revolutionary Russia – to the Great War, Easter rising and civil war Ireland of the early 1920s and beyond, when 'the country houses lit a chain of bonfires', and the tobacco-growing 'Sinn Fein Countess' tempered a life of privilege with work for Horace Plunkett's Co-operative Societies and the United Irishwomen. Daisy Fingall writes from an intimate knowledge of the leading figures of her day and their milieu. A sparkling parade of personalities – Parnell, Wyndham, Haig, Markievicz, Edward VII, AE, Shaw, Moore and Yeats – comes alive under her pen. Seventy Years Young reanimates a proximate but forgotten past with all the power of first-class fiction, and the glitter and rarity of a Faberge egg.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1991

Ähnliche

Frontispiece

ELIZABETH, COUNTESS OF FINGALL.

SEVENTY YEARS YOUNG

MEMORIESof ELIZABETH, COUNTESS OF FINGALL

Told to PAMELA HINKSON

“Those whom the Gods love die young.” (They never grow old.)

Contents

ExcerptTitle PageILLUSTRATIONSACKNOWLEDGMENTFOREWORDCHAPTER ONECHAPTER TWOCHAPTER THREECHAPTER FOURCHAPTER FIVECHAPTER SIXCHAPTER SEVENCHAPTER EIGHTCHAPTER NINECHAPTER TENCHAPTER ELEVENCHAPTER TWELVECHAPTER THIRTEENCHAPTER FOURTEENCHAPTER FIFTEENCHAPTER SIXTEENCHAPTER SEVENTEENCHAPTER EIGHTEENCHAPTER NINETEENCHAPTER TWENTYCHAPTER TWENTY-ONECHAPTER TWENTY-TWOCHAPTER TWENTY-THREECHAPTER TWENTY-FOURCHAPTER TWENTY-FIVECHAPTER TWENTY-SIXCHAPTER TWENTY-SEVENCHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHTCHAPTER TWENTY-NINECHAPTER THIRTYCHAPTER THIRTY-ONECHAPTER THIRTY-TWOCHAPTER THIRTY-THREECHAPTER THIRTY-FOURINDEXPlatesCopyright

ILLUSTRATIONS

Elizabeth, Countess of Fingall

Elizabeth, Countess of Fingall46

Thomas Fitzgerald” 47

Killeen Castle” 114

The Earl of Fingall, M.F.H. ” 115

Theresa, Marchioness of Londonderry” 162

Field-Marshal Earl Haig” 163

Hermione, Duchess of Leinster” 176

“The Old Master,” Robert Watson, M.F.H.” 177

Ballydarton” 200

Sir Horace Plunkett in Ireland’s First Motor-car” 201

The Right Hon. Gerald Balfour” 230

“The Countess Cathleen”” 231

George Russell (“A.E.”)” 242

Stowlangtoft, 1896” 243

The Right Hon. George Wyndham” 270

Elveden, December, 1902” 271

Elveden, January, 1910” 300

Elizabeth, Countess of Fingall” 301

The Right Hon. Sir Horace Plunkett” 378

Lord Killeen at Cologne” 379

Lady Lavery” 402

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I wish to offer my most grateful thanks to my collaborator Miss Pamela Hinkson for her help in writing this book. I also thank Mr. Walter Callan, Mr. Gerald Heard, Countess Balfour, Dr. R. I. Best, Miss Charlotte Dease, Dr. Myles Dillon, Mrs. W. M. J. Starkie, Dr. George O’Brien, Mr. T. U. Sadleir and Mr. Robin Watson for their kind assistance and encouragement.

E. M. FINGALL.

FOREWORD

Lady Fingall ends her memoirs on a sombre note: a neighbour’s house has been burned by republicans during the Irish civil war; a messenger has arrived at Killeen Castle with the grim news that it is next on the list; the Earl and Countess gather their most precious possessions, huddle up to the study fire with the shutters closed and await the dreaded knock, retiring eventually in the pale light of morning. Killeen escaped then. The knock came sixty years later, long after the castle had passed from family hands, when a wing was set on fire during the H-block protests of 1981.

SeventyYearsYoung is an important book. The Earl and Countess of Fingall were members of the ancienrégime who, unlike many of their aristocratic contemporaries, did not pull up stakes and depart after independence, but chose to live on in what must sometimes have seemed to be an uncongenial, if not inhospitable, homeland. Lady Fingall was renowned for her ability to make friends and many of the influential figures of turn-of-the-century Ireland, and England, are quickly, if lightly, sketched in these pages. Her relationship with Horace Plunkett, one of the enigmatic personalities of the period, which remained central to all her extracurricular activity after her marriage, is more fully explored.

Lady Fingall was a Burke from Moycullen in Co. Galway. In 1883, after a whirlwind courtship, she married the eleventh earl, when she was seventeen and he twenty-four. Plunkett was the family name, and the Fingalls inherited a seat in the House of Lords. The Plunketts were heirs to the three peerages of Fingall, Louth and Dunsany. During the penal days the lords of Louth and Fingall remained Catholic, while the Dunsanys, in order to retain the family lands, became Protestant. When the necessity had passed the lands were returned to their Catholic kinsmen, but the religious distinction stayed in place.

Fingall, the ‘somnolent Earl’ (he regularly dozed off after dinner), was as dull as the Countess was lively. Vivacious rather than beautiful, with a quick intelligence and a gregarious nature, she longed for travel and society, while he confined himself to horses and the great hunting county of Meath. It was an unorthodox partnership which might not have lasted as it did had she not discovered a sympathetic companion, and one who would provide a ready outlet for her talents, in the neighbouring castle of Dunsany.

Lady Fingall’s relationship with Horace Plunkett is the thread which holds this book together. It lasted (probably unconsummated – he was an exceptionally fastidious man) without ever rupturing the friendship with his cousin, the Earl. He remained a bachelor for the sake of Lady Fingall and was unquestionably in love with her. However, Bernard Shaw was to remark many years later, ‘Yet I never felt convinced that he quite liked her.’

Plunkett is now remembered as the father of the co-operative movement in Irish agriculture. He is less well known as one of the leading moderates in that critical era between the fall of Parnell and the polarization of Irish politics during the first decade of the twentieth century. The third son of Lord Dunsany, he was threatened with tuberculosis, which swept away two members of his family, and spent almost ten years cattle-ranching on the high, dry plains of Wyoming. Returning to Ireland on his father’s death in 1889, he mounted a campaign persuading Irish farmers to adopt co-operative methods of processing and marketing. A Protestant educated at Eton and Oxford, Plunkett was an unlikely campaigner among the farmers of the south and west of Ireland, but his sincerity and idealism were such that within five years a federation had been established (the Irish Agricultural Organization Society – now the Irish Co-operative Organization Society) with several hundred member societies (co-operative creameries) attached.

It was a staggering achievement, but represented only the first part of a larger strategy, for he united farmers and industrialists, north and south, Catholics and Protestants, in an ultimately successful attempt to extract from the British administration Ireland’s first independent government ministry, the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction (with himself as Vice President), supervising farming and vocational education in the whole island.

Lady Fingall was, of course, involved with these schemes. She acted as hostess at Plunkett’s dinner-parties and as interior designer for Kilteragh, his house in Foxrock; she grew tobacco in her garden and cider apples in the orchard (‘Bottle of the Boyne’ was to be the slogan); and, in 1910, inspired by AE, in conjunction with the poet Emily Lawless (another Plunkett cousin), she became a founder-member of the United Irishwomen, which was a prototype for the Women’s Institutes in Britain, and flourishes as the Irish Countrywomen’s Association today.

Plunkett’s position was, however, vulnerable (he had been an MP since 1892) for he had challenged the political statusquo. Lady Fingall describes the attacks on him, and on his movement, which came from both sides of the political divide. Unionists, in 1900, drove Plunkett from his parliamentary seat in South Dublin; and seven years later the nationalists had him replaced as Vice President of DATI by the uninspiring T.W. Russell.

Lord Fingall died in 1929, and Horace Plunkett in England in 1932 (as a Free State senator he had been burned out by republicans during the civil war). Lady Fingall moved to a flat in Mespil Road, Dublin, where she entertained on Thursday afternoons. (Terence de Vere White has included a charming picture of these occasions, and of an ageing, fragile but still vivacious Lady Fingall, in his autobiography, AFretfulMidge.) She died in 1944. Her memoirs, commissioned by Collins and dictated to Pamela Hinkson (daughter of the poet Katharine Tynan) had appeared seven years earlier. One tantalizing feature is the collection of letters from distinguished acquaintances which are quoted verbatim, and which have since vanished. Lady Fingall herself discloses that she destroyed Earl Haig’s letters – they described too many manoeuvres (not all, possibly, on the battlefield). Enquiries of her descendants produced only a typescript of the memoirs (now in the National Library of Ireland) and the guest-book from Kilteragh (now in Trinity College Library). The typescript quashed rumours, current in Dublin for some time, that the original version of Seventy YearsYoung contained racy passages, later omitted on the advice of George O’Brien, the cautious Professor of Economics at UCD. It remains, however, a fascinating book, none the less so for Lady Fingall’s throwaway remark, made in later life to a much younger contemporary: ‘My dear man, I never slept with either King Edward or Sir Horace Plunkett!’

Trevor West

Trinity College, DublinApril 1991

CHAPTER ONE

MY memory is like one of those toy kaleidoscopes, into which children used to look long ago. (I am still thrilled by a glass paperweight containing a miniature cottage and a figure walking towards it, which you have only to shake, to see both lost in a most realistic and thrilling snowstorm.)

Into the kaleidoscope I looked as a child. A myriad colours moved before my wondering, delighted eyes. Blues, greens, reds, pinks and gold. They were never still. How should one catch them and put them into a pattern, making them as quiet, as beautiful as the scene in the paperweight when the snow lay on it again?

I have the same difficulty as I sit looking at this kaleidoscope of life. The colours move and dance. They are now bright, now dim, clear again, dazzling. But there were all the lovely shadowy moments, the half lights, the indefinable things. How should one recapture or convey the magic of these? The dim gold evenings when one walked or talked with a friend. The dreams we had, the visions we had, when we were young, with gallant, foolish hearts to put right the world, which had waited so long only for us to put it right! There is magic not to be caught or put down in cold print. What can one say of childhood, except that it was childhood? And that conveys everything. I begin at the beginning and cross so easily those long, full years. So safe and strong is the thread by which one finds one’s way back to childhood. All that the years have held cannot make a wall to stop one’s passing. Last year, the year before, ten years past, are farther away, harder to reach, than this enchanted country that lies just within a gate of which one has never lost the key. And, having said that, I am just in time to contradict myself. I shall contradict myself as often in this book, I warn my readers, as I have contradicted myself during life. How dull life would be, indeed, if one were always to agree with oneself! “I am a multitude,” A.E. said once, when confronted with two articles of his, one of which flatly contradicted the other. There was a year between them. But there might be only a minute, and I might change my mind as I have often changed it, before I come to the end of a sentence. And I am a multitude. I take A.E.’s phrase and shelter behind it. The Japanese, in their art, discovered how dull a thing regularity could be. There will be no rules in this book, no straight road with milestones beside it, heavy blocks of stone as dull as tombstones, to tell you how far you have come and how far you have yet to go. It will wander as pleasantly as a country road, of which there are still a few left; a road made for travelling feet of men and women and children and animals, a road on which one may dawdle and go as one pleases, climbing the bank sometimes to look over the hedges if there is something beyond them to take one’s fancy. The small things one passes on such a road are as important as the great, and they remain in memory, measured according to the eyes that saw them.

The Back Door of my childhood’s home and the scenes at it, stand out clearly, when meetings with Kings and Queens and world-famous people are vague and half forgotten. The road is as one travels it, and many travellers might go the same way and, describing it to each other after, not discover it to be the same. There are stretches when the sun is on it and flowers growing on the banks (meadowsweet and wild roses in Ireland) and one lingers longer on such a piece of road. And there are miles that drop out altogether, and one does not know how one progressed from one village to the next, only that one arrived.

I have read somewhere that a memoir is a trap for egotism. Certainly one cannot avoid the use of the pronoun I, so I make no apology beforehand for the number of times that it will appear. It is quite impersonal to me in any case, for I have discovered that after all, although the gate opens, I cannot enter into that lost enchanted country. It is not that the key turns rustily or that the hinges creak, as all the keys and all the hinges of garden gates that one knew in childhood, used to do. The gate is wide and someone moves inside. But it is not I. Someone else, someone I can see as impersonally, as detachedly as though I had never met her before, saw and did these things of which I am going to tell. She is the chief performer on this stage, but only—in the manner of Ruth Draper—so that she may bring other performers before you, and present, if she can, a picture of a life that is now quite done with, a world that is ended. A life and a world, which, perhaps, for all their disadvantages and injustices, had beauty in them for some people, and effort and music and glamour and romance and colour and many dreams. Now things are much more evened up and fair, which is right, but the streets in which we walk are also more uniformly grey. We were very, very busy in those days, and now we have almost nothing to do except to sit by the fire and tell our reminiscences, and wonder if we really could have seen and known the things of which we tell.

There is a gauze curtain over the stage, I discover, such as we used in the days when we did tableaux at the Chief Secretary’s Lodge when Gerald and Betty Balfour ruled there—highbrow historical scenes of Irish history, with a view to improving our own minds and the minds of the audience. Seen through the gauze, the stage has the appearance of something in a dream. And it has a dream-like feeling to me, this stage on which someone I once knew is about to play showman. She will begin at the beginning and do her best. Be patient with her. She is no historian. Dates. They are as elusive as fireflies, as the little brilliant moths that flew before a child on the bogs of Connemara. One lays one’s hand on this and that, as one used to close it over the exquisite trembling wings and then open it to find an empty palm. So one abandons many of the dates, with the milestones of the straight machine-made road, planned for motors. And turning back to a world in which motors were once not dreamed of—and into which they came then as strange, rare and terrifying machines, there is the wandering country road on which one may do as one pleases.

The showman—or woman—can only give you the scene as she saw it, not explaining why this or that made an impression, or why so much was forgotten. Is a memoir a trap for an egotist? Certainly it cannot be written impersonally. If one were to try to keep the teller out of it, it would be like a room without a fire, a book without a heart. Because it is a life. I make no claim for it, or excuse for it; but for those whom it interests, this is how we lived. And no one certainly will ever live like that again.

In a dream—or reality—I stand, a child again, in the light of a Connemara evening. The lake water, which I can hear moving softly against the stones, is black and mysterious. The light is on the mountains, but it passes the lakes by. There is long shadow under the blue beauty of the mountains, and the little cottages are lost in it as though they had shut their eyes and gone to sleep. And I am eight years old, a long, thin child, with spindly legs and hazel eyes—that is all I remember of myself. I was a little “fey,” as I was told then, often.

“Don’t be going after the fairies, Missie,” an old man has just said to me. In his coat of white Galway bainin, and with his blue innocent eyes, he might have come, himself, from fairyland. “For if you once start going after them they will never let you alone.”

For the moment I am safe by the edge of the lake, since the fairies do not come near water, of which they are afraid. So I will not linger here, because I have run away to look for fairies, leaving my small brother and sisters in the nursery, with our new genteel governess, recently imported from Dublin, and as miserable in the wilds of Connacht as any one might expect her to be. I have slipped out without any one noticing me. For quite a long time before I put this plan into action, I had sat in the nursery with the others, free already in spirit. While I appeared to be listening dutifully to whatever Miss Murphy was saying, my eyes were turned towards the window, through which I could see the bog with the sun lighting it after rain. I could smell the mixed scent of turf smoke and wet gorse, without indeed being aware of it. It was simply the smell of the country, of the world in which my small years were lived—a wide world, it appeared, with Lough Corrib bordering it and the bright blue crags of the Twelve Pins guarding it. So disembodied was I already, that I seemed able to slip through the old house and escape, without any danger of being seen or discovered, as though I had wrapped myself in a magic cloak.

The house is always a little dim even on a spring or summer day. It smells of old wood and the boards creak under a child’s feet. In summer the many little moths from the bog and the lake’s edge come to fly about the landing with vague beautiful flashes of colour; sometimes we find them, alas, dying against the dusty windows, having beaten their wings on them in an effort to get back to the sunlight. I pass, going on tiptoe, the door of my father’s study, which is called the Magistrate’s Room, and from which he rules the district as a firm and just autocrat. At this hour the door stands open. My father is out in the fields, sitting under a large cotton umbrella like a patriarchal figure, watching his men while they work; now and again talking to them in Irish. The umbrella is made of bright yellow cotton, lined with green, and Father sits under it because he is half blind and his eyes cannot stand the sun, even the intermittent sun of Western Ireland. That umbrella, however, protects him from rain as well.

Or, he is looking at his woods and loving them, or considering his land as though it were something alive, stooping over it, because of his half blind eyes. He is a good farmer, and he makes his men work. In that picture of him, he is like the Master in the Bible.

As I creep out of the house and through the shrubbery, I see my mother walking in the garden that is peculiarly hers. Sometimes she works in it, her beautiful hands, which are perhaps her one and only vanity, carefully gloved. She grows pansies and violas and primulas and such softly coloured, gentle flowers in a pattern about the roots of an old twisted thorn tree, which must not be cut down because the cutting of it would bring bad luck. We children can see the thorn tree from the window of the room in which we sleep. In the dusk, or clear on some night of full moon, it is like an evil old man—tortured, perhaps, by his own sins—and we are afraid of it.

My mother wears grey alpaca, which makes a small rustle as she walks with her full skirts, a little cap on her head and a shawl. She has a collection of shawls and we never see her without one.

She is dreaming, too among her flowers, the far-away look that we know, in her pale blue eyes. If one of us should be hurt—if I, running through the shrubbery, should stumble over one of the protruding roots, and fall at once into the soft earth and the hard despairing hurt of childhood, she would come back from her dreams. I should be picked up, washed and bandaged, comforted. A little absent, a little impersonal, my charming, aloof mother would be, rendering these services. And then, I think, I should be forgotten. And she would return to that world in which she lived as she walked between her flower beds.

If I had passed her by, instead of hiding in the dark, chill dampness of the laurels, she might say: “Daisy …” with her air of faint surprise. She is, I discover now, rather like a mother bird, who brings up her children, throws them out of the nest and is then done with them.

To-day my mother is not thinking of me, evidently. (We are all, she believes, safely in the schoolroom in the charge of the new governess, who, she hopes, will prove a success.) I get safely through the shrubbery, where a few months ago a carpet of snowdrops glimmered beautifully under the dark leaves. At the wicket gate that leads on to the road, I hesitate between temptations. There is the bog with the wind over it, the exquisite softness of the wet soil when I take off my shoes and run over it, barefoot, like all the peasant children; and the little wood of Killerania where Spanish gold is buried, as every one knows, and where fairies play between the bluebells with the hidden gold under their feet. Or there is my Tree, a copper beech, growing against the wall, and spreading its great branches over the road, so that a climber, hidden in it, may see, herself unseen, the whole world come and go. It is my great hiding-place when I have run away from my nurse, or from the genteel governess, who is greatly to be pitied, I realise. Could she have known what she was coming to, when she turned her face towards this wild land and these half-savage children?

I see the world from the branches of my Tree. Not so far down the road is the small village of Moycullen, with its white rain-washed walls and the bright blue spirals of turf smoke rising above the yellow thatch. And now (I wander for a moment) it is a summer afternoon, with the bog and the lake lying glistening under the sun. (But somehow the sun never got into the cold lake water to warm or light it.) The white bog cotton is blown across the brown bog before the wind, like scattered snow. Hidden in the thick foliage of the copper beech, I am lost in delicious coolness. Then comes the trot, trot of horses’ hoofs. It is Bianconi’s Long Car, going from Galway to Clifden, carrying passengers and mails, our touch with the world. The road was one of those made by Nimmo in the previous century, when he discovered in his road building how well the Irish could work for themselves and how eager the people were to help in opening up the country. Anything, anybody, might arrive by Bianconi’s Long Car, a vehicle which came and went, raising a cloud of gold dust of romance with its wheels. On this particular day, for some reason, it has no passengers, and the driver pulls up to rest his horses under the shade of my Tree. He and the conductor look up and admire it, quite unaware of my small peering face lost amid the leaves and my listening ears. I lean forward against one of the branches. (I can feel now the cool sweet smoothness of it against my hot little brow. It felt like the satin of my mother’s best frock when a child’s face touched it.) In my excitement I nearly fall. What a surprise the men would get if I were to tumble down on top of them!

Is there a rustle of the shining leaves? They do not hear it. And, presently, the horses are whipped up again, and with trot, trot, and the sound of wheels, I hear the car go on, on its immense journey by Oughterard, where horses are changed, to Clifden and the coast.

But now, on another day, after a moment’s hesitation, I go through the wicket gate, passing my Tree. Across the road is the high grey wall of the garden. The trees had been planted and the garden made, before the road was cut through our property.

In the garden one is very young and lost, with the high wall made higher by the ferns and the red and white valerian that grow on top of it. Everything that will grow here at all, grows luxuriantly. There are red-hot pokers, tall enough to frighten a child, half their height! I can see them now, flaming beautifully through the mist of some late summer morning. There is an apricot tree against the wall on which yellow apricots grow, that are small and very sweet. We steal them when the gardener is not looking. If, for instance, being coachman as well, he has put on his faded green livery with its smell of many years of rain and turf smoke, and his old top-hat which has great dignity, although the silk of it is worn and rough, to drive our mother on one of her rare visits to our neighbours—the Comyns at Woodstock, or the Martins at Ross, where Violet Martin and her brother Bob are still in the schoolroom, and the immortal partnership of Somerville and Ross and the fame of Ballyhooly still undreamed of. Or, to Galway town to do her monthly shopping, from which expedition my mother will return with the parcels piled as high and wide as they will go on top of the old brougham and every available corner inside packed as well. So that it seems indeed as if she must have bought the whole of Galway.

But on these shopping expeditions we two older children, Daisy and Florence, are often taken too, perhaps to keep us out of mischief, for I can think of no other reason for filling further a vehicle that was full enough already. And, from among the parcels piled round us and on top of us so that we are half-buried, our small, rather sick faces (the road was appalling and the brougham swung and rolled and pitched like a ship) must have looked out a little strangely at other travellers on the road as we passed them.

Sometimes clothes had to be bought for us, winter overcoats and shoes and such things, at Moon’s, the big shop, which seemed a place of wonder and colour and enchantment to us. It is still there, and not so much changed from the shop I remember, when we climbed the narrow street to it, pushing our way through an endlessly exciting crowd of dark-haired fishermen and shawl-covered women, all talking Irish and busy and alive with their own affairs. The men who filled the Galway streets—not always fishermen—wore the wide black hats which they wear to-day and in which Jack Yeats has painted them.

At Moon’s, in the room upstairs above the street, we were measured and our needs considered and then, going downstairs again, my mother bought needles and cotton and tapes and such things. Afterwards we would go out and buy fruit for ourselves at a stall in the Square. The stall was bright with oranges and russet apples and brown nuts and long bars of gaily-coloured sugar-stick, as it stood against the grey background of the Galway houses. The woman who kept it wore a gaily-striped skirt of many colours, with a little black shawl forming a bodice, and she had shining dark hair parted in the middle and twisted at the back of her head. Many years later I was to discover that she and her fruit-stall made a Goya picture. But, of course, I had never heard of Goya then. We called the woman of the fruit stall “the Lady Anne,” and treated her with great respect, but I have no idea at all what was the origin of this grand title. She was part of the Spanish colour which Galway had then as now, a descendant, no doubt, of some Spaniard who had sailed his ship into the Bay in the days when the Tribes of Galway lived within their walls and traded with France and Spain.

Our shopping over, it is time for us to turn homeward. The clock in the tower of St. Nicholas’ Cathedral, built by an ancestor of mine, has just given Galway the time. We hear the hour strike beautifully as the brougham trundles heavily through the narrow streets, past the great Spanish houses with their carved heads and their courtyards, which the builders of Galway—Burkes and Blakes, Morrises and Martins and Lynches and so on—made for themselves when they came back from their travels, bringing with them more than the Spanish wine which filled the holds of their ships. We are too sleepy to glance at the carved plaque set in a ruined wall, which commemorates one of the famous deeds of Galway; the hanging, by Lynch, the Sheriff, from this very window, of his own son, for the murder of a Spanish guest who had aroused the young man’s jealousy. The history of Galway records that Lynch, having performed this stupendous act of justice, since no one else would do it, never spoke again.

The brougham pitching as we get to the open sea of the Connemara road, I feel very sick and my seat is changed. Presently I fall asleep and continue in uneasy slumber with the parcels falling about me, half in dreams, half in reality, until we draw up before the lit, welcoming door of Danesfield.

When I ran away to look for fairies and my absence was discovered, my mother would forget her garden. I think the faint dust of anxiety that I knew, would come to her blue eyes: “Daisy. Why will you do such things?” And, at the moment of the search for me, she is interrupted, by the arrival at the back door, where she dispenses her charities and her medical supplies, of Mrs. O’Flaherty, whose child is ailing, for the very reason that he has gone after the fairies, the poor misguided boy. And the fairies would have taken him surely, if it hadn’t been that he was dressed in petticoats, a wise precaution which careful mothers of Connemara adopted in those days. Apparently the fairies had little use for my sex, which explains perhaps why I escaped. I wonder what my mother’s prescription was? Castor oil, of which we had brought back an ample supply from Galway last week? Ipecacuanha wine, a thrilling-sounding medicine? Anything with such a name must be efficacious. Gregory’s Powder?

Meanwhile I have a respite and the whole magic world is mine. It is my world and belongs to me and I to it. Any one who is born in Connemara and gives their heart to it, is never really quite happy anywhere else. I run over the bog, barefooted, dancing with joy. From my earliest years I have danced as often as I have walked. It was good at eight years old to be alive and have the bog before one and the many-scented wind across it, in one’s face. Now and again I stand still to press my toes into the soft springy soil, and see the brown water ooze between them. What a lovely sound it made! I often stood like this, watching my toes disappear at last, and I know that the bog soil and the bog water gave my feet something that they kept all through life. All my joy in dancing later, the wonderful service my feet have given me, I am sure I owe to my Connemara bog, and my early, barefooted walking on it.

I turn towards the wood of Killerania, where the fairies are. I am more interested in them, than in the Spanish gold which is hidden there, although my father and I have sometimes talked seriously about that, wondering whether it could be found. And indeed it would have been useful at Danesfield. Once, at least, I saw a rainbow drop its arc of colour among the trees of Killerania. So the gold was there! And one had only to dig to find it. I thought, one of these days when I was older, I would take a spade and dig until I came to it. I was sure that I had marked the secret spot where the rainbow ended.

My father, who is watching his men work while I am with the fairies, is a big man with a long brown beard. In a later memory of him that beard is white. He is a Galway Burke. To any one acquainted with Irish history, that says everything that need be said about our family. And for those unacquainted with that history, the story would, perhaps, have no interest.

I am tempted to dwell upon it, but I resist the temptation. I may mention just that the first of the family, a de Burgo, came to Ireland with Strongbow and received from Henry II. a grant of the lands of all Connacht. If neither William de Burgo, nor his descendants, were able ever to take possession of the property which was nominally theirs as the result of this generosity (!) they nevertheless asserted their leadership most forcibly and left their mark wherever they went. Two descendants of William de Burgo were those famous Normans who took off their English garb by the banks of the Shannon, renouncing, with it, English nationality and English speech, and, putting on such clothes as the Irish chiefs wore, became “more Irish than the Irish themselves.” They and their descendants built castles about Ireland and particularly about Galway, which they made their own county; and held them in turn against the English King and the native Irish. One of those castles stands still, in ruins, at Oranmore, on the road to Galway—dreaming over the water that creeps in to its walls from the Atlantic, to lie there as still and quiet as a lake, reflecting the skies and the sunset. There was a period when the de Burgos, having defeated the Irish O’Conors at Athenry, ruled the entire province, from the Shannon to the sea. They built much of Galway town, including St. Nicholas’ Church, in the vaults of which many of them were laid at the end of their vigorous and stormy lives, and the wall about Galway itself, which was designed to keep the wild Irish at bay, with its inscription over the West Gate: “From the ferocious O’Flaherties, good Lord deliver us!” That was O’Flaherty country into which I looked, when, as a child, my eyes turned towards Connemara. But the O’Flaherties had been driven farther even than the “Hell or Connaught,” to which, in a later century, Cromwell consigned the Irish. From the Shannon to Galway Bay, the de Burgos ruled, but in the desolate land of Connemara, the “ferocious O’Flaherties” awaited their chance of cattle raiding, to take back some of their own. Hardy sheep or cattle may find a living on that bog or mountain, searching between the heather for a small stretch of sweet pasture, but it is of little use for anything else, although it held such riches for a child who loved it.

My father’s land was almost the last stretch of good land on the Connemara road. His woods were the last woods too, and, in my memory, they seem to stand like outposts of an advancing army, looking across the wild Irish country, as my ancestors, who took the land, might have sat on their horses, looking towards Connemara, but going no farther.

The Burkes, like other great families, whether Irish or Danish or Norman, were constantly changing the side on which they fought. And there was a period during the great days of Galway, when a by-law decreed that neither O, nor Mac, nor Burke should “strutte” in the streets of the town. Nor should any citizen receive into their house or “feast else” one bearing any of these names. Galway then had a mint of its own and a Governor (several of Galway’s Governors, at another time than that of this decree, were Burkes), and its own by-laws.

I do not know at what time my ancestors took possession of the land about Danesfield. It was a long white house with a rounded bow at either side, and steps up to the front door, built probably a hundred years or so before I was born. It was not beautiful without, and inside, the furniture was Victorian. We were mid-Victorian then as our furniture was. Queen Victoria had been on the throne for nearly thirty years when I came into the world. But, standing again in memory in that hall, or on the wide landing upstairs, outside the door of the little room that was used as a chapel and where Mass was sometimes said, with my father in his locally spun tweeds as server, I feel that indefinable thing that the house held. The smell of it, the faint mustiness, the dust, lit by a ray of sunlight coming through the window. The brooding peace and security within those four walls. It remains for me the house that held childhood. No other house in all the world can ever be the same.

Or—another memory—a child still, I am curled up in one of the big chairs in the Magistrate’s Room, watching my father receive rents, interview his tenants, or administer justice. No one seems to have objected to a little girl’s presence on these occasions. And sometimes I look on at exciting scenes indeed. There is a day when a lunatic is brought before the magistrate to be committed to an asylum. Poor thing! She comes in between two enormous policemen, a tiny little woman like a small brave bird. Suddenly, without warning, she springs at my father and catches him by his beard, holding on to it with superhuman strength. She has pulled him half-way round the room before the astonished policemen can capture her and release the magistrate.

I sit, holding my breath, in one of the shabby, comfortable leather chairs. There is a hole in the leather and my wandering fingers find it and dive into it, pulling out springs and stuffing for which I shall be scolded later. I can feel now the cold leather against my small fingers, the stuffing of horsehair, as they were lost in it.

The Magistrate’s Room has high windows and the shrubbery is outside. There is a tall cupboard against one wall. My father goes to it, and, opening a drawer, takes out important-looking blue papers. When he is receiving rents, he sits in the middle of the room behind his big desk. Near him is the rent table, with its many drawers narrowing away to the middle like the slices of a cake. A rent table now is a valuable antiquity. Then it was a usual piece of furniture in an Irish country house. Each drawer had a name on it, and the rent, being received from that particular tenant, was put inside, and a note added to the name, of the amount paid.

Sometimes a man or woman would come in with a long story—and how long a story in the rich Irish tongue could be, and how expressive! The men wore cut-away coats and knee breeches and carried their low top hats in their hands. The women wore scarlet petticoats—of Galway flannel—and black or brown shawls which they drew over their faces, half-hiding them, mysteriously. My father, who knew all of them and all their affairs, knew who was speaking the truth when he or she declared their inability to pay. Rents were often forgiven or reduced. Frequently they were paid in kind and we adjourned to the yard to see a load of turf from the bog tipped out of its cart and measured.

Again, to the Magistrate’s Room, they brought their disputes and quarrels, of which they had many, arguing them out before my father in Irish, which, with its ninety-five sounds to forty-five in English, is the language of all others in which to conduct a quarrel. They had the land hunger of the Irish and especially of the Western Irish, and often the quarrel was about land and mereing fences and such things. My father, who was known as “Blind Burke,” sat at the table, looking at them with the glitter of the cataract in his eyes, listening. When he gave his judgment they hardly ever went against it. They had the Irish passion for litigation, a passion he shared with them and which was to cause us trouble and embarrassment later, on our travels abroad. So, probably he understood better and sympathised with them. Instead of going to the lawyers and the courts, they came to him, having complete trust in his justice and in his wisdom. In the same way they consulted him about all their business. Indeed, they took hardly any step without first asking his advice. He knew them all by name and they were all Paddy and Mary and Mick and Annie to him, as their children were. The troubles and joys of their lives—there were more of the former than the latter!—touched him as closely as his own. He was the Master to them, as my mother was the Mistress, and neither ever failed them in an hour of need.

My father spoke and understood Gaelic and we had an Irish-speaking nurse. She wore a white-frilled cap such as French peasant women wear, a petticoat of scarlet flannel and a checked apron with a little black shawl crossed over her bodice. She taught me to speak Irish, and family tradition has it that my first words were spoken in Irish. “Faugh Sin.” (“Get out of that,”) I am reputed to have said, clutching my mother by the skirt and pulling her out of my way, because I wanted to look at something and those voluminous skirts blocked my view. Otherwise I remember little of my nurse, except that she rubbed my face ferociously with soap and water, giving me a distaste for having my face washed or touched which I have kept ever since. She left my nose with an upward tilt which was straightened out later when I fell on it in one of my first falls out hunting, with greatly improved results to my appearance, I was told by my heartless friends! As a proof of psycho-analysts’ theories it is a fact, that never, in a nursing home or elsewhere, have I ever allowed any one to wash my face, since I grew up and attained freedom in such things.

My memory of the drawing-room at Danesfield is that it was a shabby, rather faded room, and very little used. There was a table in the middle of it, on which a glass case, holding a bouquet of wax flowers, stood, with a crochet wool mat under it. Round this decoration books were arranged with an appalling regularity and tidiness, which forbade all thought of their ever being read. On the chimney-piece an old French clock ticked under its glass shade. By it, the minutes that we were allowed in this room were numbered, and when it struck a certain dim chime, like some sound coming from a world a long way away, it was time for us to go to bed. There were whatnots about the room, with bits of old china on them and shells and such things, and an ottoman, on which one might sit as uncomfortably as in a railway station waiting for a train. Sometimes my mother lay on the sofa in the bay window, to read. She could look up now and again and see, through the window, without moving, what her children were doing in the shrubbery and if they were at the work to which they had been set, weeding the flower beds. Sometimes she would put away her book, and a beautiful Rosary beads, which some one had brought her from Italy, would slip through her fingers. Was she praying, then? I do not know. She was religious, but not dévote, I think. She was passive as far as file would let her be. I think of her sometimes as a lovely slender ship, blown before the strong winds of my father’s temperament. She would have been content to lie at anchor in some peaceful backwater, undisturbed by winds and storms. But, all her life, she will do what other people want her to do. Although—I realise—she surrenders her will to my father and later to us, it is only her body that we have. She slips into her own world, her own quiet, still waters, lying here on the sofa, her fingers playing with the Rosary. Or she is lost in a book. It may be a bound volume of AlltheYearRound in which a novel by Mr. Dickens appears as a serial. She will keep that serial to read aloud to my father, later.

Sometimes, for no apparent reason that I can discover, unless my mother has heard that such is the custom elsewhere—in England, for instance, from which distant country our neighbours at Ross have recently imported a new governess—the two eldest of us are dressed up in our best frocks and our most befrilled trousers, and we go down the wide stairs, hand in hand, to my mother in the drawing-room. And she, having evidently forgotten this arrangement, looks at us as we stand in the doorway, with the most charming surprise—and, after a moment’s uncertainty—pleasure. It is on one of these occasions, that, gazing at me as though she saw me for the first time, my mother says: “You have a face like a wild flower …. like a daisy.” That is how I come to my name, the name by which my friends are to know me always, although I have been christened Elizabeth.

There is an old musical-box which is a great treasure. It stands on a table in the drawing-room. On it is painted a picture of a lady and gentleman in the most lovely clothes, bowing to each other before they dance the minuet. What are the tunes that it plays? I cannot remember, although I can hear now the faint silvery notes that suited the atmosphere of the Danesfield drawing-room. I am allowed, as a great treat, to wind the musical-box.

Our mother had always an air of repose, in the intervals of her busy life. She was eternally occupied, yet never hurried, coming and going on her feet that were beautiful like her hands. She was perfectly made in every way. And when she died many years later, the doctor said that he had never known a case in which the machinery of a body had worn out so perfectly and simultaneously, no one strength or limb failing before the other. There was no sad decline or maiming for her. All the machinery ran down together and the clock stopped.

Only now do I wonder about her. Children accept their parents, with their love, their charm, their peculiarities and whims, not considering them or wondering about them. They are as inevitable as life and the security of childhood, not to be considered dispassionately. Is my mother happy with her somewhat hard and tempestuous husband? Are they suited to each other? She seems to love him. “George,” she says sometimes, helplessly, looking at him rather as she looks at us when we do something surprising. At the moment we are two perfectly-behaved children. Incredible! And how long will it last? And is this the effect of the new Dublin governess, who has spent quite a lot of time since her arrival, looking out at the rain-swept bog, her own face as tearful as the sky? She is at least as successful as the English importation of the Martins, who had stirred my mother’s unusual envy until the afternoon when she took us, visiting to Ross, and, as we waited for our hostess, heard one of the girls call upstairs, “Mother. H’all the little Burkes are in the ’all.” After that my mother ceased to be envious of her neighbours’ ambitious acquisition.

CHAPTER TWO

MY father remembered the last Famine, and the scenes at the door of Danesfield, when he had helped to lift sacks of flour and Indian meal on to the backs of men who staggered under the weight of them. Everything that the landlords had then, they shared with the people. I am speaking of the good landlords, of course, not of the absentees, whose sins were to be paid for by all of us. My father remembered the people dropping by the roadside on their way to the Big House for help, the “coffin ships” going out from Galway Bay. Those emigrants who reached America alive, were to establish a race sworn to implacable hatred of England. He remembered the smell in the air that foretold the blight, and sometimes when he stood looking at the land, without seeing it, he would lift his head, sniffing for a warning which he would understand if it were to come again.

In my childhood the people were terribly poor, and bore their poverty with apparently complete resignation. They were deeply religious, and accepted literally the teaching that this world was only a road to the next. What did it matter then, if it was hard to walk, when it led to such unimaginable bliss? We children used to visit them in their cottages on the bogs or in the village, where we were welcomed beautifully.

“God save all here!” we would say, standing in the doorway, blinking for a moment in the turf smoke and choking until we grew accustomed to it. “God save you kindly!” the answer would come.

Out of the obscurity their faces look at me as they looked then. Lined with suffering, but dignified and often beautiful. They received us like kings and queens, and frequently, unknown to our parents, of course, we sat with them to their meal of “Potatoes and Point,” taking the good flowery potato in our small hands and dipping it into the herring dish in the middle of the table which was the “Point.”

The young people went to America, leaving the old and the sick at home. And the old people stood on the quays until the ship was out of sight, wailed and keened as for the dead, and returned to the terrible quietness of a little house from which the young are gone. Sometimes, after years, they came back, having made a fortune. A returned American was one of the possible exciting fellow passengers beside whom someone might sit on Bianconi’s car. I don’t think that we ever travelled by that vehicle. In our lumbering brougham we were safe from the wind and rain on winter days when Bianconi’s car swung past us, lifting its passengers to the mercy of the elements as only an outside car can lift them.

They were good sons and daughters, those Irish boys and girls, and the Mail carried in the “well” of the Long Car brought regular money home from America to make life easier for the old people. The Long Car carried many parcels in its “well” besides Her Majesty’s Mail, and the conductor was a sort of general messenger for the people in the villages. He brought food supplies, an odd bit of bacon as a treat, tea and sugar, or the herring that was to be the point to the potatoes. He brought other things—cottons and sewing-materials for the women, tobacco for the men. The arrival of Bianconi’s Long Car was the great event of the day in all the villages through which it passed. The whole population would turn out to receive it, and the conductor, bringing his flushed face out of the depths of the “well” after diving for the last package, still had time to tell the news or say a word about politics. Then the driver would whip up his horses and the Long Car would continue on its journey.

Leaving us, it went on into Connemara and the country that had once been the O’Flaberties’, but, in my childhood was Martins’ country, although that now only by name. The Martins were one of the Norman “tribes” of Galway and had lived like the other families of the “tribes” for a hundred years or so inside the walls of the town, trading with France and Spain and building fortunes with their trade. Until, in the sixteenth century, there was a general moving out from within the walls and the Norman “tribes” discovered the country of Galway. The Martins cannot have been very good business men, for the land they took to themselves, 200,000 acres of it, was true Connemara country, bog and mountain and lake. They built on it, Ross, still the home of one branch of the Martins at the time of which I write, and Dangan and Ballinahinch Castle. It was at Ballinahinch that the most famous of that famous family lived—Richard Martin, the promotor of Martin’s Act of 1822, the first Act to be passed in any parliament to protect animals; and the man who, more than any other man, established the moral conscience of England with regard to the treatment of animals. This new conscience was proved by the act of 1835, protecting all domestic animals, which was passed a year after Martin’s death.

Galways keeps its stories of Richard Martin and I heard them, naturally, as a child. He was a characteristic Galway gentleman, brave, violent, wildly generous, but also intensely pitiful. He lived in the great days of Galway duelling, when his neighbours were known as Blue-Blaze-Devil Bob, Nineteen-Duel Tom, and so on. He himself bore the name Hair-Trigger Dick, But it is as Humanity Martin, or Humanity Dick, that he is remembered.

The Long Car travelled through Oughterard and took the road that had once been Richard Martin’s “avenue”—of which he had boasted to his friend George IV., when he called him to admire the Long Walk at Windsor, that it was forty miles long. And the travellers on it could look towards Ballinahinch. But the Castle had already passed from the Martins then and the last of that branch had gone to America. No wonder. For the stories were still fresh in my childhood of the wild and extravagant hospitality at Ballinahinch in Richard Martin’s day and of the reckless giving to any one who asked or was in need, that had left the one time King of Connemara to die at last in poverty, an exile at Boulogne. I heard tales of the immense kitchen at Ballinahinch and the feasting in it when the whole countryside came to be fed; and of how, often, the beggars on their way there lined the avenue—an exaggeration, of course. Perhaps they lined one of the many miles of it.

Galway then was full of stories. Across the waters of Corrib Lake stood the Castle of Menlo, where Sir Val Blake’s doings kept a countryside amused and delighted. They had splendid names, these Galway gentlemen, and the whole life was gay and rich and spacious, generous and wildly extravagant. No wonder that the crash came at last.

I don’t think that I ever passed Ballinahinch in those days. Distance was still distance before the coming of motors, and the other side of the county was a long way away. Our life in our corner of it was very quiet, although we knew vaguely of the gaiety of the East side, where the Blazers hunted their incredible country of stone walls, so close together, bordering such small fields, that those who hunted there must have been in the air most of the time. It was that life that gave Galway the reputation it had then, of being the gayest county in Ireland. We had few neighbours and my father was unsociable and my mother, although she did so much, delicate. Or perhaps the delicacy was imposed upon her. I cannot believe that it would have been any great strain to her to put on that grey satin dinner dress—which, on the rare occasions when she wore it, rustled so beautifully to a child’s ears, and touched with such magic and glamour a child’s cheek—and go out to dinner. Sometimes, if rarely, this did happen. And, as rarely, people dined with us. The proof I have of this fact is a characteristic one. I remember two naughty children creeping down the stairs to loot whatever might be left on the tray, put down for a moment outside the dining-room door.

There was no great extravagance at Danesfield. For all of us, I suppose, it was the closing page of that chapter. I think the good wine that had been famous in Galway still filled many of the cellars—claret from Bordeaux and port from Portugal and Spain. Buttered claret was much drank by the gentlemen, and I heard stories of the manner in which much of this wine had been brought in, not paying any duty.

When my mother read aloud to my father and to us, on long winter afternoons, beside the dining-room fire, I used to sit staring at an enormous sideboard against the opposite wall. It was decorated with heavy carved heads and there were strange marks defacing it, and here and there, the heads were damaged. That damage had been caused by bullets fired by intoxicated gentlemen, trying to prove their sobriety in this manner, before they collapsed to spend the rest of the night under the dining-room table. Had I heard that story from my parents, or in the nursery, where the servants and my nurse told stories over the fire and looked into the coals to read the future, or sought omens in teacups? I do not know. But there is somewhere, another picture, a thing seen, or a thing told—to an imaginative child the wall that keeps the two apart is very thin, and confusion easy—a gentleman being assisted on to an outside car in the early morning, at a hall door, and held there by a faithful servant as the car drives away.