Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

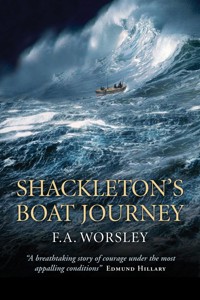

On August 1, 1914, on the eve of World War I, Sir Ernest Shackleton and his hand-picked crew embarked in HMS Endurance from London's West India Dock, for an expedition to the Antarctic. It was to turn into one of the most breathtaking survival stories of all time. Even as they coasted down the channel, Shackleton wired back to London to offer his ship to the war effort. The reply came from the First Lord of the Admiralty, one Winston Churchill: "Proceed." And proceed they did. When the Endurance was trapped and finally crushed to splinters by pack ice in late 1915, they drifted on an ice floe for five months, before getting to open sea and launching three tiny boats as far as the inhospitable, storm-lashed Elephant Island. They drank seal oil and ate baby albatross (delicious, apparently). From there Shackelton himself and seven others - the author among them - went on, in a 22-foot open boat, for an unbelievable 800 miles, through the Antarctic seas in winter, to South Georgia and rescue. It is an extraordinary story of courage and even good-humour among men who must have felt certain, secretly, that they were going to die. Worsley's account, first published in 1940, captures that bulldog spirit exactly: uncomplaining, tough, competent, modest and deeply loyal. It's gripping, and strangely moving.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 214

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SHACKLETON’S BOAT JOURNEY

This eBook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

This edition first published in 2000 by Birlinn Limited

First published in Great Britain by Hodder and Stoughton 1940

Copyright © The Estate of F. A. Worsley Introduction copyright © Hugh Andrew 2000

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-546-8 ISBN 13: 978-1-84158-063-0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Contents

List of Illustrations

Members of the Expedition

Introduction

PART I

From the Endurance to Elephant Island

PART II

Shackleton’s Boat Journey

I

II

III

PART III

List of Illustrations

Entering the pack ice of the Weddell Sea

The Endurance under sail

The wake of the Endurance

New leads in the pack ice covered with ‘iceflowers’0

How the pack ice breaks up under pressure

Deck of the Endurance after a snowfall

Endeavoring to cut the ship out of the ice

Caught fast in the ice

A dog team in very rought ice conditions

A great castellated berg that menaced the ship

Photographer Hurley at work

Heavy blocks of ice rafted up and tilted by the pressure

Frank Wild with dog team leader

Clark in the biological laboratory aboard the Endurance

Midwinter, 1915

The Endurance battling blocks of pressure ice

A night photograph of the Endurance

Return of the sun after the long winter darkness

The Endurance caught in a pressure crack

Wreckage of the Endurance

Frank Hurley and Sir Ernest Shackleton at Ocean camp

Ocean camp

Young emperor penguin chicks

Death stalks the floes

A pinnacled glacier berg

Pulling up the boats below the cliffs of Elephant Island

The first meal on Elephant Island

Tending to the invalids

The rocky ramparts of Elephant Island

The James Caird being slid into the water

The men left on Elephant Island digging a shelter

Skinning seats on Elephant Island

Glacier and mountains, South Georgia

South Georgia

Hut in which members of the expedition lived

Inaccessible mountain

Members of the expedition on Elephant Island

Arrival of the rescue ship off Elephant Island

Saved!

Maps

South Georgia Island

Shackleton’s Boat journey

Members of the Expedition

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Leader

Frank Wild

Second in Command

Frank A. Worsley

Captain of Endurance

H. Hudson

Navigating Officer

L. Greenstreet

First Officer

T. Crean

Second Officer

A. Cheetham

Third Officer

L. Rickenson

Chief Engineer

A. Kerr

Second Engineer

J. A. McIlroy

Surgeon

A. H. Macklin

Surgeon

R. S. Clark

Scientist

L. D. A. Hussey

Scientist

J. M. Wordie

Scientist

R. W. James

Scientist

G. Marston

Artist

T. Orde-Lees

Motor Expert

F. Hurley

Photographer

W. McNeish

Carpenter

T. Green

Cook

A. Blackborrow

Steward

J. Vincent

AB

T. Macarty

AB

A. How

AB

A. Bakewell

AB

T. McLeod

AB

H. Stephenson

Fireman

A. Holness

Fireman

Introduction

by Hugh Andrew

Barely three seconds afterwards the very air quivered under the thunderous crash of salvo. A light brown powder smoke blew past the ship to be carried rapidly away by the strong breeze. The fire zone was clear. The ships of the enemy’s line lay like so many ark shadows sharply silhouetted against the red gold evening sky.

It was 1 November 1914. The cruiser squadron of Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock was being destroyed off the coast of South America. On 5 November Shackleton and the Endurance dropped anchor off South Georgia. Two ages had crossed in the South Atlantic.

One was an age of guns and steel, of European empires tearing themselves apart with technology they barely understood in the mud of Flanders and on the seas of the world. It was an age of despair, of mindless murder and of evil ideologies haunting the minds of men. Only with the fall of the tyrannies of Eastern Europe in 1989 could a continent dare hope again.

But the Endurance and her crew were of another age, an age of hope and confidence when men’s horizons and ability to achieve seemed boundless and when the world seemed to offer limitless opportunities for the bold. It was in 1895 that the great age of Antarctic exploration had begun. It was the last unknown continent. The heroic figure of Fridtjof Nansen who – every inch a brooding Scandinavian giant – inspired British imitators. One of those was an obscure officer in the Merchant Marine, Ernest Shackleton, and the other a naval officer called Robert Falcon Scott. The two were to partner each other in Scott’s first expedition and then become bitter rivals. Scott was always the Establishment man, and it was the Establishment that covered up his many weaknesses and idolised his futile death in the race to the Pole. Shackleton was the outsider, marginalised by the shady financial dealings of his brother, Frank, and his own perpetual impecuniousness; marginalised too by his perpetual restlessness and unsettled nature.

But these British expeditions had a quixotic feel. The lessons the Norwegians had to teach – the professionalism and caution they lived by, the seriousness of their scientific purpose – were overruled in a spirit of Boys’ Own bravado. In the grandiosely named British Antarctic Expedition, Shackleton proposed to drive across the Antarctic! He tried to use ponies! Neither he nor Scott had any idea how to use dog teams and they only practised skiing on arrival! Their boats were unsuitable and the back-up ill thought through. Yet while these were the similarities there was one crucial difference between Shackleton and Scott: Shackleton looked after his men; Scott sacrificed them in pursuit of a dream. Shackleton was loved during his lifetime; it was death that was to transform Scott.

The Norwegians too learned to respect the men who took part in these expeditions even as they shook their heads at the amateurishness involved. Roald Amundsen said: ‘Sir Ernest Shackleton’s name will for evermore be engraved with letters of fire in the history of Antarctic exploration. Courage and willpower can make miracles. 1 know of no better example than what that man accomplished.’ High praise indeed from the conqueror of the Pole.

As an explorer Shackleton’s record is one of heroic failure. None of his expeditions succeeded (though the Norwegians felt that his first could have reached the Pole if it had been properly equipped). It was in the act of trying that he achieved his stature. And this perhaps is the summary of Shackleton’s life. He failed – but on what a scale! In this land of the long horizon he revelled in the solving of immediate problems, in the instantaneous reaction, in the situation which called for instant leadership. It was planning and the long view that caused him problems. At home the mundane problems of everyday life alternately bored and overwhelmed him. He drank too much, smoked too much, had numerous affairs, abused his benefactors shamelessly (but with hypnotic charisma) for more cash, and planned his next expeditions in anarchic conditions. But in the ice, whore survival lay on the edge, he was transformed.

The story of the boat journey needs little retelling. Worsley’s narrative is one of the most magnificent stories of adventure ever told. So gripping is it that we forget the easy mastery with which it is told. It is an epic in a little compass. And it must not be forgotten how unusual that is for an age of weighty tomes: whatever else may be said of many of the narratives of exploration of the time, ‘short’ is rarely the word associated with them! In this Worsley had the advantage of not writing an ‘official’ account. There was no element of duty involved. He could tell the story as he experienced it and describe in an unforgettable way the man simply known as ‘the Boss’. If there is a weakness in this it is that Worsley underplays his own staggering achievement in navigating by dead reckoning across a strom-rent ocean the vast distances between Elephant Island and South Georgia. That Shackleton was the leader is now remembered, but it was the follower who enabled the leader and his crew to live.

They returned to a world in which ideals and hope had been killed. A new age had begun in which men like Shackleton were an anachronism. His last expedition in 1921 was a pale shadow of his earlier triumphs. It slipped out of Britain unnoticed, uncertain as to purpose and destination. Already ill, he died of a massive heart attack on South Georgia, where he is now buried. The man whose book has preserved and immortalised him died in 1943.

If the horrors of the twentieth century marginalised Shackleton and his men, they stand now as a beacon of hope and idealism for a new century and a new era.

It is perhaps the tiny James Caird, now preserved at Dulwich College (Shackleton’s old school), which stands as mute testament to the dreams and hopes of a different age; an age when men could pit their lives against the grim embrace of the ice, the fury of the southern ocean, and emerge triumphant and exultant at the end. Truly had he ‘seen God in all his splendours, heard the text that nature renders . . . reached the naked soul of man’.

Hugh Andrew

October 2000

PART I

From the Endurance to Elephant Island

I

The Weddell Sea might be described as the Antarctic extension of the South Atlantic Ocean. Near the southern extreme of the Weddell Sea in 77° south latitude Shackleton’s ship Endurance, under my command, was beset in heavy pack ice. The temperature in February fell to 53° of frost – an unusually cold snap for the southern summer of 1914–15.

The pack ice froze into a solid mass. We were unable to free the ship and she drifted northwest, 1,000 miles during the summer, autumn, and winter. The Endurance was crushed, and sank in 69° S.

Our party of twenty-eight – eleven scientists and seventeen seamen – camped on the floes in lightweight tents through which the sun and moon shone and the blizzards chilled us. Our main food supply consisted of seals and penguins. So the ice, with its human freight, crept northwards – 600 miles in five months.

On 9 April 1916, the floes broke up beneath our feet. The northern front of the pack was being smashed by the autumn gales of the Southern Ocean.

We launched the three boats which, by desperate efforts, we had saved from the wreck of the Endurance, and, by unremitting care, had preserved intact to now save our lives from crashing ice and furious gales.

Apart from ice and stormy weather, our deadliest foes at the edge of the ice were killer whales. These brutes grow to a length of over twenty-five feet and have a mouth with a four-foot stretch and teeth ‘according’. It has been recorded that one, after being harpooned and cut up, contained twelve seals and ten porpoises! It need hardly be said that we gave thin ice a wide berth when killers were about. They will attack a blue whale which may weigh a hundred tons. While two killers seize the great whale by the lower jaw and, bearing down, force the mouth open, two others plunge in and tear out the tongue, weighing perhaps two tons. The pack of killers devour this delicacy, leaving their unfortunate victim to a slow death.

Our position then, in mid-autumn, was 60 miles southeast of Elephant Island. This desolate ice-bound island is one of the South Shetland group and lies 480 sea miles southeast of Cape Horn. It is 25 miles long east and west, and 15 miles north and south.

Ever since the loss of the Endurance we had known that sooner or later, when we reached the edge of the pack, we must make an ocean passage in the boats to save ourselves. Months before I had worked out courses and distances to various islands of the Southern Ocean, and even to old Cape Horn himself – blast him! Wherever we broke out of the ice we knew it would be a stormy passage of hard gales, high seas, and icy weather.

The dimensions, names, and crews of our three boats to which, under Shackleton’s leadership, we were entrusting ourselves, were as follows:

The James Caird, built to my orders in Poplar, London, was 22 feet 6 inches long, with a 6-foot beam. I had worked out the maximum load which she could safely carry as 3¾ tons. She had been raised, until her depth was 3 feet 7 inches, and decked at both ends by our carpenter, which made her safer than the two smaller boats. Her captain was Sir Ernest, her crew were Wild, Vincent, Macarty, Hurley, Clark, McNeish, James, Wordie, Hussey, and Green.

The Dudley Docker, built in Sandefjord, Norway (22 feet long, with a beam of 6 feet and a depth of 3 feet), was the fastest of the three boats. Captain – Worsley; crew – Greenstreet, Cheetham, Macklin, McLeod, Marston, Kerr, Lees, and Holness. Her safe load was 1½ tons.

The Stancomb Wills, built in Sandefjord, was 20 feet 8 inches long, 5 feet 6 inches beam. She was 27½ inches deep from inside of her keel to the top of her gunwale. Her safe load was 1½ tons. Captain – Hudson; crew – Crean, How, Bakewell, McIlroy, Blackborrow, and Stephenson.

In practice we found that we were compelled to slightly reduce the loads of the boats to lessen the amount of water shipped in heavy gales. Had our men been soaked all the time in that bitter cold some would have died. The boats were named by Shackleton after his principal financial supporters.

Quoting from my log:

April 9, Sunday, 1916. Position 61° 56'S, 53° 56'W. Moderate southwest to southeast breezes, overcast stratus and cumulo stratus. It is to be hoped the southeast breeze will hold and so save us from drifting east of Clarence. (Clarence Island lay twelve miles east of Elephant Island. If we drove past these islands, out to the open sea, it would have meant the end for twenty-eight men crowded in small boats.)

At 7 a.m. lanes of water and leads were seen on the western horizon, with loose ice but not yet workable for boats, as a long swell running from northwest was bumping the floes together. In any case we could not have forced the boats through the brash ice between the floes. We packed everything ready for launching and struck the tents. After breakfast the ice closed a little. 11 a.m. Our floe cracked across the camp and through the site of Shackleton’s tent, just vacated. Lunch at noon. 1 p.m. The pack at last opened enough to launch the boats, taking sledging stores, tents and seal blubber for fuel and food. By 1.30 we had launched, loaded, and pulled clear into an area of partially open water. Shackleton had one sledge across the stern of the James Caird, and the Dudley Docker towed another. We found it impossible to manoeuvre through heavy ice with such hindrances and were forced to abandon the sledges. 2 p.m. Having made one mile on our way we were nearly caught by a heavy rush of pack ice that drove towards us at three miles an hour. Two dangerous walls were converging as well as overtaking us, with a wave of foaming water in front. We only just managed by pulling our damnedest for an hour to save ourselves and the boats from being nipped and crushed. It was a hot hour in spite of the freezing temperature.

Sir Ernest has cut our meals down to seal meat and blubber only, with seven ounces of dried milk per day for the party.

Six-fifteen. Getting dark. Have rowed seven miles northwest. Forced to stop and camp owing to danger in the darkness of the boats getting crushed by the crowding floes. Just then a long floe barred our course, so we hauled up on to it. There was the added inducement of plentiful food – a crabeater seal was there before us. It was soon killed and cut up. As we hauled up the boats, secured them and the stores and pitched the tents, Green, aided by How, cooked the best cuts!

The ‘galley’, as we loftily called the stove that he used, had been made by Hurley from the five-gallon ash bucket of the Endurance. A metal cup in the base held methylated spirit which fired sliced blubber in a small pan above. This volatilized and fired big chunks of blubber in the top pan. This attained a fierce heat, above which food was cooked in a three-gallon pot resting on two iron bars. Milk made from True milk powder was boiled in the big aluminium pot of the Nanseni cooker. Three iron supports kept the galley off the snow, and a funnel at one side guided the smoke and oily blobs of soot away from our precious food.

Our sooty-faced cook was a marvel. It seemed like a miracle when he prepared a splendid hot meal of hoosh or seal meat with tea or hot milk in thirty-five minutes from lighting the blubber fire. His only shelter from a blizzard was a piece of canvas stretched round four oars stuck upright in the snow. Clouds of oily black soot poured from the funnel. Small wonder that the cook’s face was sooty, but his cheerful grin never deserted him.

The seamen, recognizing a good man, did not exercise their time-honoured right of growling at the cook. They dared not, anyway, for Sir Ernest was the cook’s protector. He would not have guarded an inefficient man. Sir Ernest always set great store on the best food and cooking possible for his men. Owing to this constant care, none of the men under him ever suffered from scurvy.

Green’s nickname was ‘Doughballs’ – a fanciful name bestowed by the seamen to account for his highpitched voice. Greenstreet, First Officer of the Endurance, once asked me in a stage whisper, ‘D’ye think he’s had his pockets picked?’ This query was in the nature of a libel.

Watches were set, and by 8 p.m. all, except the two lookouts, were in their sleeping bags.

The nor’west swell rolled our ice floe to and fro, rocking us gently to sleep. Slowly the floe swung round until it was end on to the swell. The watchmen, discussing the respective merits of seal brains and livers, ignored this challenge of the swell. At 11 p.m. a larger undulation rolled beneath, lifting the floe and cracking it across under the seamen’s tent. We heard a shout, and rushing out found their tent was tearing in halves – one half on our side and half on the other side of the crack.

In spite of the darkness, Sir Ernest, by some instinct, knew the right spot to go to. He found Holness – like a full-grown Moses – in his bag in the sea. Sir Ernest leaned over, seized the bag and, with one mighty effort, hove man and bag up on to the ice. Next second the halves of the floe swung together in the hollow of the swell with a thousand-ton blow.

It was lucky for our seaman that Sir Ernest was powerful enough to hoist the dead weight of a man and his sleeping bag, half-full of water, on to the floe. It must have been a sudden shock to wake up floating in the sea and wet to the waist. However, the rescued one soon recovered his nerve. As the camp was simmering down, after the alarm, McIlroy bumped into him rummaging in his sleeping bag and murmuring, ‘Lost my bloody tin of baccy.’ Said Micky, ‘You might have thanked the Boss for saving your life.’ ‘Yes, but that doesn’t bring back the tobacco,’ replied the bereaved seaman. This incident gives an idea of the value our men set on their fast diminishing supply. The swell again separated the two halves of the floe. We suddenly realized that Sir Ernest, his tent mates and the Caird were on the other side.

We rushed the boat, No. 1 tent, and its inmates to safety across the crack. Sir Ernest, being last, could not hold on to the boat and got left behind in the darkness. At Wild’s shout we hove the Wills into the sea and joyfully ferried our marooned leader back to his men. Our movements were hastened by hearing a killer whale blow right alongside us.

No more sleep. Killers were blowing all round. All hands kept warm by tramping the floe and huddling round the blazing fire of seal blubber till dawn.

Every two hours we cooked more seal meat and had another meal.

To prevent boredom Micky told us how to make eleven varieties of cocktails with scandalous names for each. He also sang songs and told tales hot enough to keep the cold out. To crown all, Bob Clark made a joke – I think it was about the killers blowing us up. We amused ourselves so well till dawn that, in spite of 24° of frost, we almost imagined we were at a picnic.

This day we have seen five Cape pigeons (from the open sea), three paddys, three fulmars, ten Adelie penguins, sixteen Antarctic petrels, hundreds of snow petrels, many whales and crabeaters.

In spite of our troubles and losing sleep the whole party was in good spirits, for, at last, we had exchanged inaction for action. We had been waiting and drifting at the mercy of the pack ice. There had been nothing that we could do to escape. Now there were more dangers and hardships, but we were working and struggling to save ourselves. We were full of hope and optimism – feelings that Shackleton always fostered.

Tenth, Monday. Strong easterly breeze; overcast, misty with snow squalls. 5.30 a.m. Hoosh – very welcome after our night walk on the floe. The pack ice had closed round our floe, but at 8.10 we managed to launch the boats, load them and proceed at first with oars. Later as the ice became looser, we set sail. 11 a.m. Struck open water for six miles. As we sailed, spray flew over the boats and froze on the men and the stores. We rounded the north end of the pack, but found that in the open the sea was too heavy for our deeply laden boats. Besides the weight of twenty-eight men, we had three tents, spare clothing, our sleeping bags, ‘Primus’ lamps and paraffin, oars, masts, sails, and three weeks’ food for the party.

After conferring with Wild and me, Sir Ernest decided we must rely on getting enough seals and penguins for our main supply. He ordered that one-third of our food must be abandoned, leaving us with only two weeks’ supply.

We returned to the shelter of the pack, unloaded, and hauled the boats up on a floeberg at 3.30 p.m. There we abandoned one week’s supply of food. While we pitched the tents and secured the boats, Green raided the abandoned stores. Presently he produced the best and largest meal we had eaten for five months.

By my reckoning we made ten miles northwest today. I also hoped that the strong easterly breeze that had been blowing would set up a fair current. To make up for last night’s lost sleep we turned in at 8 p.m., the lookouts keeping a watch of one hour each.

Our floeberg was ninety feet long, and the highest part of it was twenty feet above the sea. We had a glorious sleep for twelve hours, but through the night the northwest swell increased to a great height. The surrounding floes were hurled by the swell against our home, undermining it so that large pieces continuously broke off.

Eleventh, Tuesday. When we turned out we found that we had lost nearly half of our floeberg. Strong northeast breeze, overcast and misty. Cold weather, 20° of frost.

The swell had increased to a tremendous height and the pack had closed in around us. It was as magnificent and beautiful a sight as I have ever seen. Great rolling hills of jostling ice sweeping past us in half-mile-long waves. A few dark lines and cracks sharply contrasted against the white pack were the only signs of the sea beneath. But it was a sight we did not like, for the floes were thudding against our floeberg with increasing violence. Our temporary home was being swept away at an unpleasantly rapid rate. We saw that in a few hours our foothold would be cut from under us. We and the boats would be thrown into that seething mass of heaving floes. There would have been no hope for us. It was an anxious time. Shackleton, Wild and I went to the highest point so frequently to look north for open water that one or more of us were on the lookout there all the time. Before lunch we had made a track to the summit that looked as though a regiment had passed there.

The undermined banks broke away at such a rate that twice we had to draw the boats back into safety.

After what seemed an eternity we saw a dark line – open water – to the north slowly drawing nearer. It became a race between the rescuing open sea and the collapse of our foothold.

Our floeberg was about eighty feet deep in the sea, so that its base, fortunately for us, was caught by a different current. This carried it towards the dark band of welcome sea.