Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

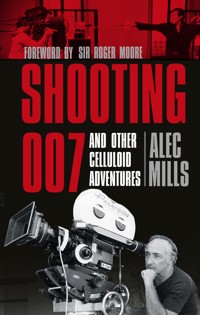

In Shooting 007, beloved cameraman and director of photography Alec Mills, a veteran of seven James Bond movies, tells the inside story of his twenty years of filming cinema's most famous secret agent. Among many humorous and touching anecdotes, Mills reveals how he became an integral part of the Bond family as a young camera operator on 1969's On Her Majesty's Secret Service, how he bore the brunt of his old friend Roger Moore's legendary on-set bantering, and how he rose to become the director of photography during Timothy Dalton's tenure as 007. Mills also looks back on a career that took in Return of the Jedi on film and The Saint on television with wit and affection, and Shooting 007 contains many of his and Eon Productions' unpublished behind-the-scenes photographs compiled over a lifetime of filmmaking. Featuring many of the film industry's biggest names, this book will be a must-have for both the James Bond and British film history aficionado.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Lil

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Foreword by Sir Roger Moore

Preface

The Early Years

War and Peace

Carlton Hill Studios

The Navy Lark

Duty Calls

Deliverance

Back to Work

The Sleeping Tiger

Harry Waxman BSC

Father Brown

Lost

Contraband Spain

Moby Dick

House of Secrets

Strange Goings On

Robbery Under Arms

Third Man on the Mountain

Flashback …

Swiss Family Robinson

The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone

Walt Disney

Blow-Up

Moving On … Moving Up

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

The Hunting Party

The Tragedy of Macbeth

A Former Dweller

A Family Thing

Gold

The Hiding Place

Operation Daybreak

Shout at the Devil

Seven Nights in Japan

The Prince and the Pauper

My ‘Mate’ Ollie

The Spy Who Loved Me

Coincidence?

Death on the Nile

Moonraker

A Cardiff Paint Job

Avalanche Express … The Awakening

Running Scared

Visit to a Chief’s Son

Sphinx

Eye of the Needle

For Your Eyes Only

Return of the Jedi

On the Third Day

Negotiating Salary

Meet Jim … or Perhaps James?

Octopussy: My Private Revolution

Hot Target

Shaka Zulu

Lionheart

King Kong Lives

The Living Daylights

Television Flashbacks

Licence to Kill

Bloodmoon

Dead Sleep

A Changing Industry

Christopher Columbus: The Discovery

Aces: Iron Eagle III

Coincidence … Again?

The Point Men

Reflections

Summing Up

The Phantom Returns

Appendix: Filmography

Acknowledgements

Plates

Copyright

(© 1982 Danjaq, LLC and United Artists Corporation. All rights reserved)

FOREWORD

by Sir Roger Moore

I can’t think how long I’ve known Alec; it feels like forever – and I mean that in the nicest possible way! We’ve shared some interesting times, whether it was hundreds of feet underground in a South African goldmine, on an orbiting space station or on a nuclear submarine planning to destroy western civilisation as we know it.

The one thing I enjoyed most about the Bond films was coming together with a family to make the movies, and Alec was a long-standing member of that family. Well, not long standing in the vertical sense as he isn’t that tall, as the box he often stood on to help him reach his camera viewfinder will testify. But in terms of talent and personality, Alec is a big man.

At the time of writing, I haven’t yet read my old friend’s autobiography, so I cannot really make any comment about its readability. However, if he tells the truth about the shocking way I behaved on film sets over the years, on various continents, above water and below, above and below ground, then I think you will be amused and appalled at the disgraceful way some actors behave because of the inflated egos that they develop due to their good fortune.

If, on the other hand, Alec just boasts of his artistic achievements in the world of cinematography you will have to believe it, because Alec does not lie … except when he is writing or talking, as I discovered on the ten or so happy occasions we worked together.

Knowing Alec, I can safely promise you a good read, and I always tell the truth.

Sir Roger Moore

PREFACE

I well remember my mother, Lil, reading fairy tales to me in bed to try to get me off to sleep. I was young and believed everything she read from the book to be true. Mouth wide open and totally convinced that all this could be a way of life, I slept well. Many years later I wondered if I had been brainwashed and had had my future played out before me on the 10-inch black-and-white Murphy television set which my parents somehow managed to buy. Lil smiled when she reminded me of those past early years as we strolled down memory lane. In a strange way, those scenes reflected both my life and career, somehow mirroring those fairy tales.

I had to think carefully about how I would write about my life and profession. I want not only to write about the film world – so unlike the current technology of high-definition digital cameras – but also to share my hidden emotions, which may be difficult to explain. But I will try …

Autobiographies of my predecessors, the people who contributed much to my filming education over the years, were useful, as were my personal experiences in a fast-changing film industry. Those experiences are not easy to describe now, with new technology moving on and leaving behind a generation of ‘oldies’ to salvage past memories. With my generation of film people now fast in decline, I suddenly felt the need to explain my own images, particularly when reading Sir Roger Moore’s memories of me; indeed, I have memories of Sir Roger, which I will come back to later. It is also necessary to establish personal images of my early background which may be of interest to others. My story is one of a retired generation and it may be difficult for the modern reader to understand our environment. I and others came from a world that is now seen as past history as the evolution of the film industry continues on its journey with its fast-changing technology.

‘Past history … that’s right, accept it’s too late to argue about that now – we are what we are,’ Suzy quickly pointed out, looking over my shoulder as I made a few notes. Suzy was always ready with her opinion, even when discussing my possible retirement. At the time I had hated the very idea but my caring wife thought it would be worth considering and that I should wake up to the fact that the phone had finally stopped ringing.

‘But I’m not dead yet!’ I said, fighting back.

This issue inevitably brought up the subject of my appalling memory, an unfortunate inheritance handed down from Lil and now more noticeable as I struggled to recall fast-fading reminiscences while keeping alive the idea of writing an autobiography – private moments for the family to enjoy before all are lost to memory. We were both aware that I would need to do something in retirement, more than likely retelling past adventures and experiences. Even if they were recorded out of sequence, my accounts would remain as honest as memory allowed.

Then I asked why an old fool would want to reveal his private life – exciting as it was – when it would be easy to disguise the reality to his advantage. In all likelihood all those who take on the challenge of writing their memoirs are tempted by this.

‘I assume you mean taking licence?’ Suzy asked, reading over my shoulder … wish she wouldn’t do that!

I enjoy reading autobiographies, usually of those with whom I worked in the past, though there were times when I hardly recognised the author, the person I thought I knew. So now I wonder if the writer had an outside influence suggesting that a little exaggeration of past experiences would be accepted – even if it was not entirely honest. With this in mind, I felt I must look carefully to what I write, should I take up the challenge. My book should be interesting to read, perhaps entertaining, while at the same time it would need some licence to flow, to keep the reader’s interest – which is easier said than done. Should the thought of retirement finally become reality, we would probably move to Devon, where Suzy and I could look out across the glistening water breaking over the rocks bordering our garden – the perfect atmosphere for ageing memories to flow back. Again, this is easier said than done; in truth, I would always be captive to an occupation that dominated my life.

There are many better qualified in putting pen to paper with their entertaining wit while remaining comfortable in their humility; at this early stage I’m not sure where I stand on this one. With these humble thoughts in mind and the constant maltreatment of my wife who bullied me into accepting this late challenge to write of past experiences, I knew it would be a difficult task to face up to, even more so should I tell the ‘whole truth’. I suppose the only reason I accepted this challenge was in part my refusal to accept any awareness of passing years. Like friends and colleagues before me, I am well into the chapter of holding a pension book, so perhaps delaying acknowledging the truth was my denial of growing old, hoping to delay the inevitability of my retirement. Be that as it may, my physical condition remained good for my age – brain still functioning normally, my enthusiasm and energy have never faded. It was there for all to see. The problem now was that the phone had stopped ringing. Suzy was right – I had been rumbled … What to do?

It would be easy to sit down in a comfortable armchair and reflect on days gone by, making notes or perhaps watching one of my old films on the telly, if only to lift my morale, my self-esteem. But this would inevitably depress me too, knowing that my work could have been better had it not been compromised by schedules which were more important for the director; at least I could improve the lighting in my head. I supposed I could also do a little gardening, which I really hate. More than likely I would just sit there dozing, waiting for the Grim Reaper to come calling. Obviously, my thinking was becoming negative, allowing depression to set in.

As a result, I decided to take a second glance at my colleagues’ autobiographies – those directors and cinematographers with whom I had the pleasure to work. I had gained knowledge through these people’s kindness when I pestered them for information – how they did this or why they did that – hoping not to become a pain in the bum! My options remained open about what I thought I should do, or perhaps what I should not do. There was a long way to go and I was still not confident about writing a book.

Slowly a more optimistic attitude grew within me and I felt positive about the challenge to join this well-known club of authors, but this was soon followed with disturbing negative feelings when I reminded myself of the famous names who had already and successfully taken up the challenge to write of their personal experiences; I doubted I could match their accomplishments. Again I was quickly reminded this was ‘unhelpful’ to the cause. I pressed on despite my concerns, while at the same time knowing that my attempt would produce much the same subject matter as other books, scripting the same theme but with different labels attached. Already I was convinced that my efforts would be a waste of time, and possibly less interesting anyway.

‘That’s not the point of this exercise!’ Suzy whispered in my ear.

So now I considered being more controversial, writing kindly of those whom I respected and had the pleasure of working with, while others would be treated with the contempt they deserved – diplomatically, of course. In the end both would feature in my story, leaving me grateful for their part in my challenging career.

Here I should point out that it was never my style to sit back and say nothing when an honest opinion ought to be voiced, if necessary disagreeing with an egotistic authority and questioning his opinion. Silly me, thinking I would be safe with this approach! There were times when it would have been wiser – indeed safer – to remain silent when sensing disagreement, allowing others to dictate the conversation without reasonable discussion. However, this was not in my character and sometimes it resulted in people having a negative attitude towards me personally, but even at the time I knew that I would have hated myself for not voicing an honest opinion. I will come back to this later, along with the ensuing consequences.

After all the problems that came my way in this ever-changing industry, it was now time to look back on my small part and see how ‘my scene’ had played out in this special profession. If I am honest, my career seemed to come my way by chance. Later, I came to believe that things in life do not necessarily just happen by accident!

With my working days now over, I started to ask questions of myself – had I achieved all that I hoped and worked so hard for? On balance, I believe that I have, and happy I am to admit this, in spite of my failings – which I also intend to share with anyone who might be interested. My aim is to hold the reader’s interest by telling my version of the truth, or at least as near to the facts as memory allows.

I was advised to keep my account of my personal life to a minimum, as readers would be more interested in my film work. While I believe this to be true, on thinking about it further, I decided that it would be dishonest to the reader if the real Alec Mills did not surface or was not even recognisable. I decided not to go along with that false image. ‘I am what I am,’ for better or worse, come what may. This personal account will be a private evaluation of both my life and career.

It was my good fortune that life pointed me to an industry which is so out of the ordinary, action packed and rewarding that after sixty years of working in the world of films I cannot recall a day when I did not look forward to going to work. In all probability, that is true for many who work in the British film industry. Fortune surely smiled on me in allowing me to progress with some of the great British and European cinematographers of my time, not forgetting those directors who played their part in influencing my work later on. From the age of 14 my career was completely dominated by these incredible people who were so generous in their support to this young fool, so if I claim some measure of success through idol-worship, then so be it! I would happily plead guilty to that.

The observations you will read come from a selection of personal experiences which over the years have given pain, joy, tears and laughter, all of which gave me much to reflect on as I wrote. More than likely some of the continuity will be awry but – with apologies to Eric Morecambe – I’m playing all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order!

However, before my film career comes to dominate the book, there is a part of my history which can only be established in my own way: my early background, where I came from with recollections from my early years during the war. In a strange way these experiences would point me towards where my future would eventually take me. A humble life with a happy ending – a real fairy tale!

Should you decide to read on, you will learn how a foolish young boy ceased to exist the day his schooling came to an end, and all because of a woman going by the name of Lil. However, for you to understand this sequence of events in their proper context, I would ask your patience, with the need to go back to school, where my story really begins, and where to this day I still remember my teacher saying …

‘Mills … this is just awful … really awful!’

Mr Lee, my long-suffering school teacher carefully studied my paper, occasionally changing his vision by taking off his spectacles to study my nervous state as I stood in front of his desk. He tapped his ruler on the small table in the way we students recognised as a bad omen and he followed the gesture with the predictable overstated deep sigh before returning to read the drivel in front of him – my ‘composition’, as it was called in those days.

He was right, of course; we both knew that. His comment simply underlined an attitude that I had to my early schooling in the years during the Second World War, now long past. It would be fair to say that under the teaching skills of Mr Lee my school days could be described as nothing short of disastrous. Now, seventy years later, I sit in front of the computer facing up to the reality of his teaching, hoping to reclaim past history which at times may well be embarrassing. I still remember the grin on his face, the nodding head suggesting that I was doomed to fail in life. At the time I would have agreed with his judgement; I was without doubt a terrible student. To complete the image I paint of my teacher, a veteran of the First World War, this sad human being had a dreadful habit of spitting into the coal fire that warmed the classroom, claiming this peculiarity to be the result of a gas attack during the conflict. I can offer no such excuse to salvage my lack of interest in his teachings.

The groundwork of my education continued to drag on with little expectation of achieving medals of any kind, either academic or on the sporting field – just another frail specimen of youth who struggled to keep up with other athletes at school. In my defence, this was partly due to bad attacks of asthma, most of which were blamed on the black and yellow smoke pouring out of the tall chimneys that spread their pollution across the capital, the main contributor to the famous London fogs. Even so, it cannot really be used as an excuse as I do not recall ever staying away from school because of my condition – Lil would make sure of that. Should I look for any excuse for my academic failings, I would point to Hitler’s never-ending bombing of London and the changing of schools with different teachers due to the bomb damage, which I hope gives some explanation for the continual interruptions in my education. In all honesty, I should also admit to a certain lack of self-discipline. Whatever excuse I may offer, there was little continuity in my schooling during those dark days when living in the capital was dangerous, although for a youngster it could also be exciting. Now, of course, I regret those wasted years; I am what I am and the clock cannot be turned back.

Even so, images from those war-torn years would linger, and still remain in my memory. One recollection was of Lil with concern on her face as she put her comforting arms around me as the bombs of the nightly visits of the Luftwaffe fell around us. It is an unfading image of a loving mother which is perhaps difficult for the current generation to understand.

I was relating these experiences to Suzy, who threw down the gauntlet challenging me to mention these experiences in these memoirs.

‘Did you tell Simon or Belinda about your war?’ she asked, using my children to highlight my parental failings.

Strangely enough, I had never considered it. Suzy made an interesting point with that comment, so now it was necessary for me to think more about my offspring and give them something of my past history to remember me by, digging deeper into the library of memories where I hoped something would remain from my early years. Faint they may be, but they are necessary, otherwise my story would make little sense. Bear with me …

I remember little of my early childhood, apart from the occasional flashback triggered by a photograph in the family album. As a child I never had my own bedroom. I slept in the sitting room on a put-u-up, as they were called – a couch during the day opening out to a double bed at night. When I lay in bed everything seemed scary as I stared at the distorted shadows flickering on the ceiling, projected images from the paraffin oil heater that took the chill off the cold room – central heating did not exist in humble homes then – leaving cold, unpleasant memories. My eyes scanned the dark surroundings for unwelcome ghosts who might be present, perhaps exaggerated by the crying wind coming through the poorly fitting windows. Pulling up the eiderdown, I would cover my face and I could at least take comfort from the hot-water bottle. It was frightening, but this is how things seem to a small boy.

‘England expects …’ Even in my early days it looks as if my mum and dad had me singled out as officer material.

Margate beach in the 1950s. This had always been a popular holiday resort for the Mills family and my parents would eventually retire to this town in the 1960s.

Lil was a tailor’s assistant in London’s Savile Row, where her working life was spent making trousers for the wealthy. Mum took pride in her work and was pleased to be associated with the elite tailors, but with the passing of time her hands became arthritic and her tailoring days were no more. She was a mother who scrubbed the front stone doorstep once a week, suggesting the cleanliness of the inhabitants within – a habit not uncommon in those days. Luxuries were few and far between, but a certain dignity existed in working-class families. Alf, my dad, a porter and decorator by trade, came home from work on a Friday night and gave Mum her ‘weekly allowance’ to feed and clothe us, while I would be spoilt with a small bar of Cadbury’s milk chocolate – a joy that has never left me.

My two older brothers, Alfie and John, were vaguely around. I say ‘vaguely’ with respect to them both, particularly Alfie. He died early, as a 16-year-old, having suffered the agony of infantile paralysis, which was not uncommon in those days. I remember little of Alfie, but what I do recall is the pain my parents went through when he passed away. Alfie was a much-loved son but due to his condition his legs were fitted with callipers (braces) so he could only walk with the aid of crutches. I can only imagine how life was for this young man. Should his name come up in a casual conversation, you could be sure that tears would appear in Lil’s eyes, even many years after his passing.

Yet, in spite of all the difficulties described, a highlight was the yearly ritual of going on holiday to Margate, where we would meet up with other family members to enjoy the wonders of the sea air. A daily ritual of hired deckchairs on the beach would take place as the family claimed our spot in a circle, warding off others from intruding on our territory. To complete this idyllic scene, loudspeakers on the sea front would play ‘I Do Like to be Beside the Seaside’ – such joy! With the sun slowly burning its way into flesh, handkerchiefs now suddenly appear with four corners tied in knots fitting snugly on heads to give added protection from the fierce rays, our red faces suggesting we had had a wonderful holiday. Images still remain of ladies’ skirts pulled above the knees, their brown linen stockings allowed to roll down to their ankles – memories now long past …

Strangely enough, I still have pictures in my mind of visiting my grandparents. Ted Hodgson was a giant of a man, who to a small boy appeared to rule his household with great authority. Their home was always impeccably clean and had a strong Dickensian atmosphere: a mantelpiece with a dark green pelmet covering a highly polished black-leaded fireplace, not forgetting the traditional aspidistra plant housed in a flowered china pot – a typical feature of the time. Gas mantles complete the image – electricity had yet to arrive in their house. Ted Hodgson was king in his castle, while my grandmother Mary, a sweet kindly lady, appeared to know her place; but, again, all this was seen through young eyes.

The year 1939 saw the outbreak of war, which to a 7-year-old would mean little. To be honest, I don’t recall Lil or Alf being too concerned about it at the time; if they were, they certainly didn’t show it. Anyway, I had my own problems to deal with in the daily ritual of going to school – war or no war, nothing would change that!

Family discussions about the conflict remained frequent, where Dad would tell of his involvement in the First World War. If pressed, he would tell his part in the Battle of the Somme, his memories of the dreadful conditions in the trenches. Regrettably, I paid little attention to his wartime exploits, although it will be necessary to return to this sad history when I later discover more about my hero.

Home was a small ground-floor flat in a three-storey Victorian dwelling in Croxley Road, housing three families. The house had a small backyard with sheds for storing coal for the fires – the main source of heating in the home. In consultation with the other families, Alf built a small air-raid shelter in the yard which we could all squeeze into should it be necessary. Constructed of corrugated iron and concrete and fitted with basic wooden benches, the shelter would be strong enough to save our lives should the house be hit during the Blitz. As our family was housed on the ground floor we were also supplied with a Morrison shelter – an iron frame covering the bed with wire mesh to the sides – though everyone preferred to visit Alf’s work of art in the backyard.

With the Luftwaffe losing the Battle of Britain to the Royal Air Force, Hitler decided to bomb London into submission at night, the only way the Luftwaffe could protect their bombers from the British fighter pilots. This was a strange and interesting episode, if seen through young eyes. With the radar system picking up the German aircraft crossing the English Channel, an air-raid siren would tell of an imminent attack on the capital, forewarning families to rush to Alf’s safe haven. There we would all squeeze into the cramped shelter, soon to hear the pulsing sound of the German aircraft arriving above.

The bombers’ arrival automatically brought a nervous silence; no one spoke as the bombs rained down, fingers crossed as one or two exploded nearby – another even closer! This may seem strange, but I don’t recall ever being frightened by this: concerned possibly, interested certainly, but terrified – I don’t think so. Everything seemed unreal … A strange atmosphere now takes over as ladies silently pray under their breath, their moving lips betraying their inner thoughts; God’s protection was needed now more than ever! One night their prayers failed when relatives living in nearby in Woodchester Street were killed in the bombing; their home was flattened by a German bomb. My cousin Brian was the only survivor from the devastation, and he would help me later with these recollections.

The bombing of London continued, and my ninth birthday present from Hitler was the heaviest night of destruction recorded on London. As the clock passed midnight, Lil led the way with a subdued verse of ‘Happy Birthday’: a weird moment as bombs fell around us. With the sound of aircraft moving away, the tension finally started to ease, the concern now was for others with all the destruction going on around us. I leave the rest to the imagination.

When the dreaded school day was over I would amuse myself playing around on an old upright piano which, believe me, had seen better days. While my attempt at playing was not serious, I quickly mastered ‘Chopsticks’, before the reality of the night bombers returned. Self-taught, I was soon able to play the popular tunes of the day, which somehow came easily to me. ‘God’s gift’, Lil claimed, with this sudden talent emerging, and another sacrifice would be made for my piano lessons.

The selected tutor, Mr Braithwaite, was impressed with my playing by ear, but it would be a different matter when a sheet of music was placed in front of me. In spite of this, after a period of his expert tuition my never-say-die tutor was convinced that I should go the Royal Academy of Music in London and try for their junior exam. Lil was pleased that I did ‘reasonably well’, but with a changed music sheet put in front of me I was slow in transferring the challenge to the keyboard. To everyone’s surprise – not least my own – I passed the exam, if not enough to win their ‘plaudit of merit’.

Although this was an achievement, even with this so-called ‘gift’ I really wanted to give up the piano lessons, knowing that I was a ‘tinkler’ rather than a real pianist. Lil later came to accept the inevitable, realising it was a waste of time and money, though probably more noticeable was my lack of interest in becoming a musician. If truth be known, not at any time was my heart set on a music career and with a little nudge I was allowed to abandon that most unlikely idea. Perhaps in time I might have achieved Lil’s ambition, but this young lad was not appreciative of the possibilities put his way.

Lil had not given up that easily. With the accolade of my achievement at the Royal Academy, she now planned her next overconfident move, this time without telling me what she had in mind. It was time to prove what her son could do on Opportunity Knocks, the famed talent show in the days before the X Factor or Britain’s Got Talent, compered by Hughie Green. Auditions for those to take part in the show would be held at the London Palladium; it appeared that confirmation of my entry had already arrived in the post.

Lil’s big day finally arrived. With the other young hopefuls – and their equally doting parents – we all stood in an orderly line in the wings of the vast London Palladium stage, waiting for our names to be called out. Parents prayed that their offspring would win a place on the show and I shook nervously in the background, thinking of the disaster which surely lies ahead.

At the time, Richard Addinsell’s Warsaw Concerto was a popular piece which had captured the nation’s imagination. In all humility, I suppose I played the concerto reasonably well, though apparently not as well as Anton Walbrook who in the film played a shell-shocked Polish pilot who also happened to be a famous pianist. I had practised hard to get the concerto as near to perfection as my tiny hands could stretch.

The routine was simple. When your name was called by the ‘talent master’ – an indistinct figure sitting in the shadows of the auditorium – you walked to centre stage, confirming your name and what you were going to do; then you got on with it without further ado. With over a hundred auditions to be held, limited time was allocated to each ‘artiste’: a singer might get an opportunity to prove their worth, a musician possibly got a little extra time to play his piece, while a comedian’s ‘jokes’ would allow the poor talent master to cringe further into the shadows.

Slowly the queue moved forward as we watched the hopefuls performing their various talents to the talent master, whose sighs at the torment he was suffering were clearly audible before he yelled out, ‘NEXT!’ The obvious failure would then quietly exit stage right in tears as the next package of talent took centre stage and the ritual started over again, as the hopefuls indicated what particular gift they had to offer to the world of show business before proving it.

With Lil and her favourite musician at last reaching the front of the queue, the moment of truth had come. Carefully watching those who went before, Lil was convinced that the talent master would appreciate the value of this young artiste and would allow the concerto to be played without interruption. The moment Lil had been dreaming of finally arrived.

‘ALEC MILLS!’ the shadowy figure called out from the darkness.

With a squeeze of the hand for good luck, Lil eased my small reluctant frame forwards. I walked slowly to the centre of the enormous Palladium stage, where nervous tension now started to rise. Swallowing hard, I whispered my name before moving to the massive Steinway grand piano, dwarfing our old upright back home. Out there all alone where my feet barely managed to reach the pedals, and now feeling well below par, I quietly paused to compose myself (as rehearsed with Lil) as my clammy hands touched the keys ready to attack Addinsell’s masterpiece. A deep breath and I was ready for the challenge ahead …

Before I continue, I should first explain for those who are not familiar with the Warsaw Concerto that the music starts with heavy chords: twenty, possibly thirty, fortissimo chords.

My tiny hands struck the keys perfectly with the required passion. I suppose I had got as far as about the twentieth chord or so – certainly no more – when the talent master yelled out, ‘NEXT!’ with great gusto. Although this came as a relief to me, sadly the shock was too much for Lil to accept as there was no doubt in her mind, and mine, that the chords had been played immaculately. However, the decision had been made, and her darling son’s musical career was cut brutally short simply because this silly ‘tosser’ didn’t appreciate real talent – at least as Lil saw it. More embarrassment would follow when Lil crossed the stage to join me on the way to the nearest exit – the notorious stage right – pausing for a brief moment to give a cruel stare to the indistinct figure cowering from her in the shadows.

Now we turn away from the world of showbiz to the world where my interest really lay.

My passion for the cinema came early at the local church hall watching silent films of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy and other comedians of that era. It was free and therefore acceptable for the family budget to cope with. However, to visit a real cinema, to enter the sanctuary of the auditorium, required money and was a domestic luxury unaffordable in the Mills household.

Following my failure to become a musician, I decided to focus instead on other strategies that would enable me to enjoy the expense of an afternoon at the local fleapit along with my roguish pals. If we emptied our pockets, the few pennies collected would be enough to buy one ticket for a shilling to sit close to the screen. Entering the darkened hall, the holder of the precious permit would find a seat close to a side exit and, after five minutes or so, he would go to the toilet, which was usually situated by an exit door. Opening the door would allow the rest of the waiting criminals loitering outside to creep silently into the darkened auditorium, one at a time, suggesting that we had come from the toilet. This unlawful exercise usually worked well, but inevitably there came the time when the usherette’s torch was pointed directly in my face, caught out for not being in possession of a ticket. My plea of losing the receipt failed to impress the lady and I was quickly shown the exit door – the same door by which I had entered; it would seem that I was on their wanted list!

The only reason I tell this sad account was because of one occasion when we went to the cinema on a Sunday afternoon, entering the hallowed hall in the usual rehearsed illegal manner. The film – a musical, I seem to recall – ran longer than usual, making it necessary for me to run home very fast. Perspiring like mad, I swallowed a quick cup of tea forced on me by Lil before dashing out to the local church of St Simon for Evensong, where one of my many labours was to sing in the church choir, earning money for my visits to the cinema. With the film having run late, I made the service with seconds to spare. Rushing into the vestry, with the help of the elderly choristers, I quickly put on my black cassock and white surplice, possibly wearing a tilted halo after cheating my way into the cinema. With the organ already playing, a Bible was thrust into my hands and it was time to adopt the customary slow pace on entering God’s house. Mr Elliott, organist and choirmaster, cast a glance in my direction and was obviously displeased with my late arrival and flushed appearance. Even so, I quickly adopted the required angelic look for the measured walk to the choir’s pews, where, along with the congregation, we sang our hearts out to the Almighty. But the Lord was not pleased with Alec this day, nor was this the first time I had been late for my religious duties, and now, finding myself further in debit on my account with Him, it was time for the reckoning; time to teach Alec a lesson.

The evening service usually ran for an hour or so but soon a call of nature would make the point that it had been a mistake to drink the tea Lil had forced on me. At first I was not too concerned about the problem: an hour was not long to control myself. But before long it was necessary to review the situation, which was now becoming desperate. Mr Elliott was already annoyed by my arriving late for the service – rightly so, as we were paid for singing in the choir – so with this in mind I decided not to disturb my fellow choristers, who would come to regret this decision. With the priest now well into his sermon and his attentive parishioners holding to his every word, I knew that if I climbed over the other members of the choir seated behind the cleric, the congregation would turn their attention to me. This was not school so I could not put my hand up and ask the vicar if I could go to the toilet without his sermon ending in disaster, but it was about to do so anyway as nature took its course.

With twenty minutes of the service remaining and no chance of easing my way past the choir, the hint of acid urine on clothes soon attracted the attention of my fellow choristers and the elderly vicar. The situation now turned into a Brian Rix farce, where the audience – sorry, congregation – were still unaware of what was going on as the unusual fragrance had yet to reach them. Sadly this was not so for the poor old vicar, who probably thought it could be emanating from himself. The elderly members in the choir, who most likely had similar problems in life, recognised this particular aroma and sat there, hoping it was not them relieving themselves, while others had no idea where this strange scent came from and quietly looked around to see who it could be. Eventually all looks turned in my direction, leaving my wretched life hanging in shreds. Fortunately, the choristers – bless them – reminded themselves where they were, so my assassination took place after the film – sorry, the service – was over; not that it mattered now – I would be dead when Alf heard about this!

At the conclusion of the service we walked back to the vestry, the pace possibly rather quicker than usual. Aware of my imminent demise, I rushed to the toilet and locked myself in, leaving the choir with bowed heads in final prayer to the Almighty. I too prayed, asking for divine forgiveness, protection and mercy. Then I made sure that everyone had left before leaving the sanctuary of the church.

Taking my cassock and surplice home to be washed, I had to face up to the anger of Alf, who found all this to be ‘f***ing embarrassing’ or, as Dad put to Lil, ‘It’s that f***ing film stuff he goes on abart!’ How could I challenge Dad’s wisdom – a true Cockney through and through! Speaking of my dad here, I write of a tough man who was quiet and polite in company but an entirely different animal as a soldier, which I will come back to later.

To bring this sad episode to an end: Mr Elliott decided that my services would no longer be required in the choir, so now it was necessary to find another source of income to help finance my legal visits to the cinema – which Alf kept on ‘abart’!

The year 1945 would bring the end to the war, with street parties all over London. Croxley Road was no exception and I would be required to play all the popular tunes of the day on the piano: ‘We’ll Meet Again’, ‘She’s my Lady Love’, ‘Lily of Laguna’ – all Lil’s favourites. Rationed food suddenly appeared on linen-covered tables and there was beer a-plenty. We also remembered those who had not survived, and some gave silent prayers for those who never came home, while others reflected on what could have happened had we failed. The high mix of emotions around the table is impossible to describe; the joy full of sadness even though we had won the war.

After the celebrations, my school days would also soon come to an end, leaving me with little idea of what I would do in the workplace. It is possible that I would have given way to the idea of being a musician, but even Lil had given up on that unlikely idea, perhaps realising that the answer was already planted in her son’s dreams, even if he didn’t recognise it. In the meantime, I would wait and see what came along – what life had planned for me …

I hesitated about giving this honest assessment of my early background. I was risking making a fool of myself. What would be the point? Perhaps it was a necessary part of life’s journey that pointed me in the direction of my future. At the same time it is a personal responsibility to tell of the background from which I came, if only to keep the record straight. As you see, I have no problem with this and hope to continue this way for the rest of the book.

It was 1946: one year after the end of the war, when I finally reached the age of 14. My schooldays were over and now I was ready to join the world of the working man. Liberated from the disciplines of school life, I could earn a wage. Small it may have been, but at least it allowed me to visit the cinema without sneaking in through the back door. Those days had passed; I would pay from now on.

It was possible to stay on at school until the age of 15, should I have decided to, but there was little chance of that happening with this young man. My incarceration at Essendine School was over, I was out of jail. A pleased smile on the headmaster’s face suggested he agreed enthusiastically with my decision; I knew we had something in common.

It is interesting – if not downright strange – that, with my love of the cinema, it had never occurred to me to be a part of it, in whatever capacity. However, it had not escaped Lil’s attention that this industry had given me so much pleasure and, realising where my interest really lay, she decided to do something about it. Without telling me of her latest plan, Lil found a small film studio in Maida Vale, Carlton Hill Film Studios, where the manager, Mr Robert King, agreed to interview me. As I waited for this ‘miracle’ to happen, the inevitable lecture quickly came: ‘Alec, this interview is very important. Now make sure you get this right!’ The message was loud and clear; Lil knew well that I was a cheeky little bugger who could easily spoil my own chances of winning the position.

Hair combed, smartly dressed, sitting upright, I was on my very best behaviour as I sat opposite the studio manager in his office at 72a Carlton Hill. The interview appeared to go well as I worked at convincing Mr King that I would be an asset to the studio in any capacity he may offer – clapper boy, stills cameraman … I showed him the Kodak Box Brownie camera I carried, hoping this would impress him. It didn’t. We settled for tea boy!

Smiling, the kindly manager put his hand up, interrupting the obviously rehearsed chat I had practised with Lil. He was suitably impressed with my cheeky performance.

‘You can start in three weeks; your wage will be one guinea per week.’

A fortune – twenty-one visits to the cinema, sitting in the front seats! To my relief – and Lil’s – no questions were asked about academic qualifications; perhaps the gentleman had been thrown off guard by this small talkative lad. Even so, he made it clear that I would need to wait a little longer before I became a cameraman, or even part of a camera crew, although that would possibly come in time.

Carlton Hill Studios in 1947. Early memories of a 14-year-old tea boy and occasional clapper boy who had the audacity to ask if he could put the clapperboard in to see himself on the screen (front row first from left). Names I remember include George Bull (gaffer, third row second from right), Donald Wynn (smiling with moustache, fourth row third from left) and sound mixer Charlie Parkhouse, standing next to Donald Wynn.

The weeks before I started work passed slowly, giving me time to consider what I would do when the big day arrived. The image in my mind was working on the studio stage with famous actors, directors shouting through a bull horn, ‘Action! – Cut!’, cameramen with caps back to front, a Charlie Chaplin image, of course.

When the big day finally arrived I found myself working in a department called ‘filmstrips’. Filmstrips were strips of film used for educational purposes, to project images at venues where lectures were held for the government’s Central Office of Information. Essentially, a series of photographs are transferred on to a 35mm negative via a rostrum camera from which positives are made, finally ending as projected images. This was definitely not what I had had in mind and far from what I had expected, but at least it was a beginning, where I would have the thrill of seeing real films being made, if only from distance. Eventually my patience would be rewarded, though it would be five long months before I finally arrived on a film set – a frustrating time for a 14-year-old lad desperately in need of becoming a tea boy! But at least the long journey had started. John Campbell, a school friend and fellow conspirator in the art of cheating ways into the cinema whose passion for films matched my own, asked me about vacancies at the studio; with my promotion to the film set the studio manger agreed to meet John.

At last my moment arrived; now came the start of a career which I would be totally committed to, and I believed this was life’s plan for me on planet Earth. The first thing to do was to join the film technicians’ trade union, the Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT). My membership number was 10578 – Brother Mills had arrived!

To repeat myself – which you will note I am prone to do – I was a small lad whom ladies described as ‘that sweet little boy’. It was a terrible start: I was a man now, a fellow worker. Even so, I quickly realised that this ‘sweet little boy’ thing could be turned to my advantage and that perhaps going along with this awful outrage could be useful. One fast learns the need for friends in the film business.

In my new surroundings I was polite and courteous to everyone on the set; if asked, I would get the ladies’ tea. Deep inside, though, something was starting to bother me. In my world of actors and technicians, not one had a cockney accent, which – to my shame – concerned me, giving me with a feeling of being left out in the cold, excluded from the circle of all these exciting people. Was this another mountain to climb? I now realise how stupid and ridiculous this was, but having grown up in a typical London family it was inevitable that I would have developed the cockney slang, along with its quips – inherited from Alf, of course. Although my accent was not particularly heavy, I was aware that a strong cockney manner could at times sound aggressive, even if softened with its traditional sense of humour. My problem was whether anyone would take me seriously.

Carlton Hill Studios in 1947, working on Vengeance is Mine using an old Vinten camera. Valentine Dyall was the star of the picture (seated in front of the camera), with cinematographer Jimmy Wilson (second row, first from left), George Bull (gaffer, second row second from left), Charlie Parkhouse (sound mixer, to the right of the lamp), Bill Oxley (camera operator) and the focus puller known as ‘Mo’ Pierrepoint because he had the same surname as the last British hangman.

Confirmation of this came when actresses moved from that ‘sweet little boy’ to ‘that sweet little cockney boy’. Obviously I had to do something to sort out this personal problem. I would hate to be called a snob, which most certainly I am not, but at the time I foolishly believed that my tone of voice together with my cheeky cockney manner was not helpful to me or my career. So came the ‘Rain in Spain’ consciousness, where a slow transition would take place. With hand on heart, I can honestly say that this was a natural fine-tuning rather than a corrective phase. I knew that I would never completely lose my cockney accent.

Of course, there are many in the film industry with different tones of voice, but for me it was a question of being labelled as different from my colleagues – stupid, I know! One successful cockney in the public eye was the hairdresser Vidal Sassoon, who came from an East End background. Please make allowances for my bad memory, but I seem to recall Sassoon admitting to having elocution lessons in order to lose his cockney accent to help him achieve success in the world of hairdressing. Like the hairdresser, I recognised the hidden rules of life, the need to adapt and work hard to climb up the invisible ladder which – as you will read later – was difficult enough, anyway, while at the same time, quietly admitting that I couldn’t afford elocution lessons. Alf would have killed me if I had asked his help in this.

Carlton Hill Studios started life as a church before its transformation into a small film studio. Here our lives were dedicated to making second feature films or short musical performances used as fill-in breaks between time-scheduled televisions programmes on the BBC. Viewers would be entertained with pretty chorus girls singing and dancing to pre-recorded playback music. This young tea boy gazed at them with mouth wide open, enjoying the moment as my dreams suffered in silence. Children’s programmes would find Annette Mills playing the piano with her puppet friend Muffin the Mule dancing on top; commercial television had yet to arrive in the UK. As I write this I suddenly realise how old I am – so be it.

Carlton Hill in 1949. Another musical slot for television with a famous personality of the day playing the piano. This time Robert Ziller was cinematographer, George Bull (holding lamp) was once again the gaffer and ‘Mo’ Pierrepoint has moved up to camera operator. By this time I was now pulling focus.

On my graduation from tea boy to innocent clapper boy, like those before me I was required to do the shopping for the camera crew’s needs or to do anything else asked of me. Nothing would stand in the way of my progress and I drank in without question or hesitation the traditions to which all newcomers to the camera department are exposed. It was my turn now.

Reading Ronald Neame’s autobiography, TheHorse’sMouth, it would seem that I graduated from the same school of innocence as that director, where we would always do what we were told, unquestioningly. He wrote in his book that as a young boy he was sent to get a ‘sky hook’, only to be passed on from one person to another until the rude awakening dawned that there was no such thing. Eventually the kindly cinematographer Jack Cox explained the joke to the innocent clapper boy. In Christopher Challis’s wonderful autobiography, Are they Really so Awful?, he wrote of his early days as a junior assistant where he was sent shopping for the camera crew’s needs, with no questions asked, and so the tradition would continue with me.

One errand which I was sent on came from a camera operator who, you will appreciate, remains anonymous. He gave me his list of ‘requirements’ for the local chemist. Off I went, not bothering to read his list …

‘What can I get you, sonny?’ the tall lady asked, looking down at me from behind the counter.

That hurt, I’m a man now – a worker! Biting my lip, I gave her the list, which she read out.

‘Aspirin … tin of Vaseline … throat pastilles …’ she looked at me ‘… DUREX?’

Her eyes fixed on me. ‘Are they for you, sonny?’ The discourtesy continued.