14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Remembering our roots is the answer to revival.In Singing in the Streets Maria Fyfe tells her story from her upbringing in the Gorbals on the south bank of the River Clyde to her election as a Member of Parliament for Glasgow Maryhill and beyond. Fyfe takes the reader through the realities of living and growing up in the aftermath of WW2 to the pivotal days of her early life in the Labour Party. She offers a beautifully written personal, nostalgic and sometimes comic view of late-20th century Scotland. She considers class, sexism and politics and the progress that has been made – or has yet to be achieved. From council house to the House of Commons, Fyfe shows the reader that change is possible.We cannot wallow in misery. We have to fight.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

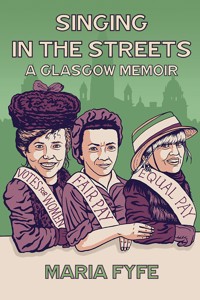

LORNA MILLERhas been causing trouble and entertainment with her cartoons and artwork since childhood and has been lucky to make it her career for the past 27 years. She is the only woman in theUKto have a weekly political cartoon withBella Caledoniaand she also works for theGuardian. She is regularly commissioned as a campaign Artist & Designer forUNSION,GMB,STUCand Common Weal. Lorna has been involved with environmental campaigns, autism and disability awareness and most recently as a member of Long Covid Scotland Action Group, having suffered ongoing health issues due to the virus.

She is @mistressofline on Instagram and Twitter.

www.lornamiller.com

The cover image brings together Glasgow women across the decades who fought for equality through the Trade Union Movement. Mary McArthur, on the left, was a suffragette who had rebelled against her Tory family to become chair of the Ayr branch of the Shop Assistants’ Union. By 1903 she was the first woman on its national executive board.

Standing beside her is Agnes McLean who led the strike for equal pay in 1943 and 1969. She was a formidable character with great style who loved to dance the rumba.

On the right, representing the successful Glasgow Equal Pay Strike, Is Denise Phillips a UNISON activist and Homecarer.

The image was originally commissioned by Glasgow Trades Council for the 2018 May Day poster.

By the Same Author:

A Problem Like Maria, Luath Press, 2014

Women Saying No, Luath Press, 2014

A Glasgow Memoir

Maria Fyfe

ISBN: 978-1-910022-23-8

Typeset by Carrie Hutchison

The author’s right to be identified as authors of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988has been asserted.

© Maria Fyfe 2020

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

Chapter 1: War Baby

Chapter 2: ‘Yes! We Have No Bananas’

Chapter 3: ‘Oh, My Papa’

Chapter 4: ‘Everything’s Coming Up Roses’

Chapter 5: ‘We’re All Going on a Summer Holiday’

Chapter 6: ‘St Trinian’s, St Trinian’s’

Chapter 7: ‘Let’s Go to the Hop’

Photo Gallery

Chapter 8: ‘Heigh-Ho, Heigh-Ho, It’s Off to Work We Go’

Chapter 9: ‘It’s My Party’

Chapter 10: ‘H-Bomb’s Thunder’

Chapter 11: ‘We’re no’ awa’ tae bide awa’’

Chapter 12: ‘Take Me Home’

Chapter 13: ‘Raise the Scarlet Standard High’

Chapter 14: ‘Which Side Are You On?’

Postscript

For Catriona, Jacob, Max and Peter, who

make their grandmother so proud.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go out to Tom Brown and Jim Cassidy for their useful professional advice; Malky Burns, Ian Davidson, Johann Lamont, Gus Macdonald, Jim Mackechnie, Des McNulty and Bob Winter for their memories of times past and/or useful comments; Lorna Miller for her permission to use her wonderful artwork on the cover of this book; Gavin MacDougall, Carrie Hutchison and the team at Luath Press; and Don and Eileen Macdonald, my hugely caring neighbours, who not only brought our local community together, entertaining with music when we were out clapping on Thursday nights for theNHSand carers, but kept me supplied with my regular newspapers, which kept me sane while the lockdown held me indoors.

Preface

BACK IN1958a gem of a book about growing up in Glasgow was published. That book was Cliff Hanley’sDancing in the Streets. As a19year old Glasgow girl I lapped up every page of it (I have always shared his Glaswegian nationalism). As a schoolgirl I had daydreamed of being a reporter, and here was this guy doing it with wit and wisdom. Back then women didn’t get to be reporters, except for food, fashion and furnishings. I earned a few pounds with such freelance work, but my heart wasn’t in it.

I found myself steered in a different direction. Labour was defeated in the1959General Election for the third time and I read my first ever political paperback,Must Labour Lose?. I felt this could not possibly be. The party that got my parents out of the tenements and into a high quality, well-built council house with gardens back and front? The party that had created theNHS, meaning no more counting coins to pay doctors’ bills? Like many other youngsters at the time, I decided to join the party and see if I could do anything to help. Cliff Hanley himself had joined the Independent Labour Party and taken part in soapbox oratory.

In similar circumstances today, it seems a good time to recount another childhood, that of a girl growing up in Glasgow, and tell the story of how the decision to join the Labour Party led to unexpected consequences. Hanley introduced his book quoting Groucho Marx’s declamation, ‘Let there be dancing in the streets, drinking in the saloons and necking in the parlours.’ But why leave out singing? I was to enjoy plenty experiences of singing outdoors and indoors. ‘The Internationale’ and ‘The Red Flag’, obviously. Trade union songs like ‘Joe Hill’. Umpteen folk songs. A whole playbook of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND)songs. Songs about the Irish rebellion – much to my parents’ annoyance. Later on, ‘Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika’, in support of the Anti-Apartheid struggle.

It seems obvious that this book should be titledSinging in the Streets. My earlier book,A Problem Like Maria, recounts my experiences in Parliament, good and bad, marvellous and insufferable. I’ve often been asked what I did before entering Parliament. Having spent seven years as a councillor in Glasgow, I think younger people especially, downcast at the result of the2019General Election, might like to know how we, the Left, fought back against Margaret Thatcher. We cannot wallow in misery. We have to fight. And part of that is getting our facts straight.

Let’s look at Scotland first. Ours is the only nation in theUKwhere the Tories lostMPs and vote share. TheSNPmessage was ‘Stop Johnson’ which was clear and simple, while Labour’s was an attempt to bring Brexiteers and Remainers together. But the simple arithmetic of the matter is that theSNPcould not keep Johnson out of Number10, even if they won every single constituency in Scotland. And the more they talked of an alliance with Labour with that end in mind, the more it reminded people of the Tory poster putting Ed Miliband in Alex Salmond’s pocket.

Johnson being Prime Minister is proving to be a good recruiting sergeant for theSNP. But scepticism remains amongst much of the public, and no amount of Saltire-waving will answer questions like how an independent Scotland would handle trade and customs arrangements with England when it is out of theEUand if Scotland rejoins. It’s hard to see how any updated White Paper can answer this until after theUK–EUtrade talks are completed.

As for Labour, a renewal of Better Together seems extremely unlikely, and I am surprised to see it mooted at all. The Tories are even more right-wing than in Thatcher’s day. Witness the likes of Kenneth Clark and Michael Heseltine urging people not to vote Tory. No, remembering our roots is the answer to revival. Remember Mary Barbour’s army and take heart.

During the First World War private landlords pushed up the rents, calculating the women would be a soft touch with the men being away in the trenches. They didn’t reckon with Mary Barbour. She and twenty thousand women refused to pay higher rent, their campaign culminating in a huge demonstration when some tenants were taken to court. Lloyd George, then munitions minister, told the court to drop the charges and a few months later the government passed the first law forcing rents back to pre-war levels. And these women did not even have the vote. Mary went on to pursue many more reforms: free, pure school milk, wash houses, public baths, mother and baby clinic, and the first women’s health advice clinic; all much needed when women often gave birth to large families while suffering tuberculosis.

The Labour movement is well aware of our male heroes. In today’s world I’d like to see them not simply revered, but listened to. They have lessons for today.

England delivered for the Tories –345out of their total of365seats. Yet there were mixed results. The north of England saw seats like Bolsover being lost to the Tories. But the right-wing media didn’t mention Labour held all the seats in Liverpool, Leeds, Newcastle and Sheffield. These cities too had had their share of being ‘left behind’. Is the explanation that city dwellers are more cosmopolitan in outlook?

Conclusion: learn from history. In1931Labour was down to52MPs, a huge drop from248in1929. Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister, was expelled for setting up a ‘national’ government largely peopled by Tories. Yet by1945it was able to win a landslide in that election for ambitious plans undeterred by the state of the nation’s finances. Surprisingly, it is the case that in our2019election, Labour won10,300,000votes. That is more than was won by either Ed Miliband or Gordon Brown. Whenever Labour’s death is yet again announced, I am always reminded of Mark Twain, on reading news he had died, commenting, ‘The report of my death was an exaggeration.’

And here’s another surprising statistic. For years I wondered when, if ever, we would achieve equal representation of Labour women in Parliament. Well, it’s happened –104womenMPs out of a203total. And some of them are already showing they are up for a fight.

Chapter1

War Baby

PERHAPS CROSSING THEU-boat infested Irish Sea with three young children was not the best idea my mother ever had. Our vessel was one of several travelling in a convoy escorted by destroyers. Anyone might think that seeing all these ships equipped with guns lined up before setting sail would make anyone think twice. Not her. It was1941and earlier that year Hitler had announced he would sink every ship that came within60miles of any Irish port. In the first six months of that year nearly three million tonnes of shipping were sunk byU-boats, so small and low lying they were hard to see even if they were above water.

I was a toddler, the youngest of the three children. No fewer than three kind-hearted sailors took turns to hold me safely as the steamer bucketed its way over to Larne, while my mother was throwing up over the side. Hence my lifelong admiration for sailors. It was not as if all she had to do was go and buy the tickets at the Burns Laird office. Permission had to be sought, and she waited months to get the go ahead. No-on asked her the famous wartime question, ‘Is your journey really necessary?’ For it really was not. There were plenty of safe places in rural mainland Britain where children were being evacuated. At least at home there were air raid shelters. An attack at sea would probably end in drowning.

In fact, we had already experienced evacuation inland, just before the war started, when Hitler invaded Poland. Children were being evacuated for fear that towns like Glasgow would be razed by German bombers. Nothing did happen at that stage and we all returned home after only three weeks because my mother could not stand another minute of the condescending manner of the chatelaine of the Earl of Inchcape’s castle near Ballantrae, where we had been accommodated along with four other families from Glasgow. Whatever it was exactly the peer’s wife did or said that annoyed my mother I never learned, but it must have been quite something to make her prefer to risk life and limb to being patronised.

So why make this journey to Ireland? Glasgow was being bombed again and again. The worst bombing nights were on13and14March1941, and the Gorbals, so near the docks and the shipyards, took a pounding on many a night. It must have been hellish, getting through those long hours, night after night in the air raid shelter, waiting for the all-clear and wondering if your home was still intact. Clydebank, only a few miles down the river, was blitzed to all but total destruction on those nights in March, leaving only seven houses out of a total of12,000still standing undamaged. I can see all too clearly why my mother wanted to get out of Glasgow without delay. She perhaps had other reasons. At that time my brothers Jim and Joe were only attending school two or three half days a week because St John’s Primary had no air raid shelter. She might have been aware that no such problem existed over in Ireland. There was also a lot of concern expressed at the time that infants, too young to understand what was going on, might get a ‘complex’ because of the fear engendered by the Blitz. I don’t remember being afraid, but I’ve spoken to a few contemporaries about this period, and we have something in common. Whenever we hear, in a war film or documentary, the air raid warning siren a shiver runs up our spines. Our air raid shelter was in the basement of the Co-operative Stores in Bridge Street, around the corner. We often had to stay all night through, until the all-clear sounded and we could go home.

And what part of Ireland were we headed to? A small town on the west coast called Bundoran. Why there? The obvious answer might have been that Ireland was neutral, and no one had any motive to bomb the Donegal coastline. Yet apparently her reason was simply that she knew Bundoran well already, as that was where her family roots were, and she had a bachelor grand-uncle Henry living there in a thatched cottage on the cliff edge about a mile south of Bundoran. My brother Jim had been intended to inherit the croft, and in recognition of this honour his confirmation name, Bartholomew, was a compliment to Henry’s elder brother of that name. But Tholm, as he was known, died, and Henry mortgaged the croft so he and his cronies could drink the proceeds.

In the summer of1941Henry was still very much with us. The family had made frequent visits before the war, so it was a wonder he agreed to let us over the door again. Joe, on entering the cottage door for the first time, when he was an observant if somewhat forthright toddler, had disbelievingly seen the hens allowed to run in and out, and remarked, ‘Whit a durty hoose.’

‘What did the child say?’ asked Henry.

‘He said it was a lovely house.’

‘Naw Ah didnae…’

‘Wheesht!’

Henry was small, gnarled and white haired, and becoming stooped and not as strong as he used to be. There was no running water in the cottage, so Jim and Joe helped him by fetching it in buckets from a nearby stream.

We didn’t remain long in the cottage. Mum found that tongues wagged in the neighbourhood at the idea of this young woman staying unchaperoned in the house of a single man, even if he had one foot in the grave, and so she sought accommodation in one of the cheaper hotels, aided by the allowance for evacuees’ accommodation paid by the wartime government.

Jim had just turned old enough for secondary school in Bundoran. What my mother had not known when she hurried us out of Scotland was that the Irish government’s policy was that all such pupils had to be taught Irish Gaelic. My mother saw no point in that as she believed optimistically we would be going home soon anyway. So she home-schooled Jim herself, no mean feat considering she had left school at14. When we returned to Glasgow Jim was advanced a year.

Joe was sent to the small local primary school where he settled in happily enough at first. Then one day one of the boys in his class spat at him, and Joe retaliated by poking him in the eye. The teacher got a heavy walking stick out of his drawer to belabour him, but not the original culprit. ‘I’m not having that,’ said Joe, and walked out, never to return. One day I was sitting on a stone wall on the road to Bundoran while Jim was patiently trying to persuade a reluctant donkey to give me a ride. The donkey gave him a dismissive kick. Then one of the local lads came along the street and jeered, ‘Aw, look at the big Jessie, minding his wee sister.’ Before Jim could draw breath I yelled back, ‘Scram, stupid appearance!’ The lad was so surprised that he did. I’ve no idea where I got this phrase from. All his life Jim told people about it. He was proud of his fearless wee sister. Ignorance is bliss, more like. Then, when I became anMP, he told people I would put up a good fight if I could see off big boys when I was only two.

We returned to Scotland after nine months in Bundoran, unable to get back any earlier because by then strict wartime travel restrictions were being enforced. My mother had been distraught at being refused permission to travel across the sea to attend her mother’s funeral in the August of1941. Understandable, but it could easily have been her own funeral – and ours – as well.

Meanwhile my dad, who had stayed at home to keep the wages coming in, was driving his tram throughout the Blitz and coming home night after night to an empty, unheated, cheerless flat without complaint. One night an elderly lady dropped a bag full of groceries when she was boarding his tram at Charing Cross and took an age to collect all the items from the wet street. He was muttering to himself with impatience as he helped her gather her bits and pieces together, because the driver could be disciplined if he was more than two minutes late. And the resulting holdup did make him late getting to Kelvingrove. Lucky for him. A land mine struck just when his tram should have been passing through.

If we had not escaped the U-boats I would not have reached my third birthday. But I had another piece of good fortune when I was born. A few years before the Second World War broke out, the infant mortality rate in Glasgow was exceptionally poor. It was the worst in Europe. You can be sure if that was how it was for the whole of Glasgow, then the Gorbals was worse. Yet I was born in robust health, with such an appetite for my mother’s milk my brothers immediately dubbed me ‘the bottomless pit’. Our family lived in a gas-lit room-and-kitchen in a tenement in Bedford Street, a main artery through the Gorbals.

The lavatory was exactly that. A toilet pan. No washbasin. A chain, too far up for me to reach, hung down from the cistern high up on the wall. This lavatory was on an outside staircase and shared with two other households on our landing. The next door neighbour had Irish lodgers, so there could be a queue of seven or eight standing around waiting. The rent was9s (45pence) a month. We lived there because our mother wanted to be near her own mother, who lived upstairs.

I was nine months old when the Second World War broke out in Europe, and when I was two I thought the bombs were coming when we were merely hurrying out of the rain. Everyone who was a young child at that time remembers their Mickey Mouse gas mask, but when you are a baby or a small infant you needed something specially designed to prevent tiny hands, in ignorance of what they were doing, pushing the mask aside. There was such an invention, and you can see it in Glasgow’s People’s Palace, the city’s much-loved social history museum, to this day. It consisted of a bag big enough to hold an infant body, the gas mask itself, and a wide clear panel to allow the baby to see out. My mother had to carry it everywhere she went with me in case there was a gas attack.

If we went out at night we needed a torch, taped over so that only a tiny pinpoint of light showed us our way in the blackout, but I was not afraid when I had my two big brothers to swing me along. At ten and eight years old, there was a big age gap between them and me when I was born. Both my brothers were black haired, like all the family, and tall for their age, but otherwise quite different in character and appearance. Jim was very lean, studious, responsible and hardworking – a typical eldest child. Joe was sturdier, very sporty and not likely to do his homework if he could get away with winging it. But to my toddler mind, both were equally to be relied upon. A favourite ploy of mine was to jump off the kitchen table without warning, in the absolute certainty that one or other would catch me.

The darkness in the street outside meant you had to watch where you were going on the uneven pavement. Besides, a bogeyman might be hiding up a close waiting to grab you and carry you away. Jim and Joe would shout ‘Boo!’ as we passed the entrance to a tenement to scare off any bogeyman that might jump out at me.

At birth I was registered as Catherine Mary O’Neill, but when I was baptised a few days afterwards the priest, speaking the words of the ceremony in Latin, instead of ‘Mary’ said ‘Maria’. My parents, not usually ones for snap decisions, instantly decided they liked this better, and so I have a name that is common enough amongst the peasantry in Latin countries, but not so common amongst the plebeians of Scotland. Parents really should be careful about their children’s initials. Mine, forming the letters ‘C’, ‘M’, ‘O’, ‘N’, inspired my uncle Johnny, my mother’s elder brother, to hail me, ‘C’mon, C’mon’, whenever he saw me, putting me in a foot stamping rage. Dad’s father, named Daniel, was born in Kilrea, a small village in Co. Londonderry. Sometime around the late1880s, when they were in their teens, he and his two older brothers were instructed by their dad to take a cow to market, but instead of going back home with the proceeds, they bought tickets for the steamer and headed to Glasgow. Their mother had died, and when their father married again they disliked their stepmother so much that this seemed their only solution. There was many a family story told about Daniel. He was blacklisted for rousing fellow workers to join a trade union when he worked in an ironworks in the east end. The union, small and poorly organised in those early efforts to represent unskilled workers, went bust. So did the company, when the striking workers brought production to a halt.

Then there was the time one Mr Healy, a wealthy man who owned a chain of ham and egg shops, a specialty common in those days, offered the local branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians a £5prize – a great deal of money in those days – for some competition or other. Granddad stood up at a packed meeting in their hall that night and expressed his concerns forcefully. ‘We cannot accept this money,’ he declared, ‘until Mr Healy pays decent wages to his shop staff.’ The ensuing row broke up the organisation and I grew up wanting to be like my grandfather. My mother had Donegal roots, and her maiden surname was Lacey. She believed she was descended from one of the sailors with the Spanish Armada who had either been shipwrecked or had decided his sailing days were over and sought haven ashore there. Her coal-black hair and large brown eyes seemed to bear witness to this possibility. Having fallen out with all her in-laws by the time I was an infant, she would say, ‘Just like an O’Neill’ every time I did something to annoy her.

I never knew my mother’s parents, my mother’s mother having died when I was only two. I was told she had a crooked little finger, which came about from working in the Dundee jute mills from about12years of age – a common minor disfigurement amongst mill lassies, that came about from using their pinkie to catch threads at an age when their hands were not yet fully developed. She always wore cotton or wool gloves when she went out and made a point of never wearing a shawl. In her day shawls were seen as a badge of poverty. Owen Lacey, my mother’s father, had a habit of standing on the corner steps of a local bank, chatting with his cronies, and that is all I remember of him. With his walrus moustache, cloth bunnet, and pipe stuck in his mouth, he looked just like Paw Broon. He worked as a stoker and ship’s greaser with theP&OLine for many years, on ships travelling to ports around the Far East, and that must have been physically demanding.

I never saw either of my father’s parents. Daney died before I was born. Although she never saw my brothers and me all these years, my paternal grandmother must have kept a place for us in her heart, because when she died in1953, when I was14, she left sums of money to us in her will. She had saved up her entire dividend over all the years of her membership of the Co-operative since the day she became a married woman, and it amounted to some £2,000, a small fortune in those days. Our shares bought suits for my brothers Jim and Joe, and my first grown up ‘costume’ bought at Pettigrew & Stephens in Sauchiehall Street. The grey wool jacket was fitted, the skirt accordion pleated and a new lemon blouse from a shop in the Argyll Arcade completed the ensemble. Whenever I went out in my new outfit, and in my first pair of Louis heel shoes, I felt a million dollars.

I wish I had known this granny to whom I owed such largesse. For years I had no idea why I never saw her. I had known about the estrangement since I was about ten years old, when I was rooting one day through the shoe box that held the family photographs. There was my parents’ wedding picture, my dad in a dark suit, my mother wearing a knee length straight white satin shift with a long lampshade fringe at the hem and carrying a huge bouquet of white lilies and roses. Her bridesmaid, her sister Mary, sat at her side. But a rough tear all the way down the right hand side of the picture showed someone was missing.

‘Who was that in the picture?’ I asked.

‘That was your uncle Patrick,’ Mum said. ‘He was your dad’s best man.’

‘But why was he torn out?’

‘I’ll tell you when you’re old enough,’ she said.

I waited many years to be told. Meanwhile I wondered what on earth he could have done. Was he a child molester? A murderer? A rapist? A spy for Germany?

It was on my32nd birthday when we were reminiscing at the fireside about the family, that she finally decided I might now be old enough to hear. As we sat together on the sofa in a grave tone of voice she said, ‘One day your dad was a bit late getting back from work, and Patrick came round to visit. He often dropped in. Only this time he had a drink in him, and he tried to make a pass at me.’

I waited for her to go on, and when she remained silent I asked, ‘So what happened next?’

‘Nothing really. Drunk as he was, he soon realised he wasn’t on. I pushed him away, and told him to get out, and he went. It was all over in a moment or two.’

‘And that was it? Is that it?’ I squawked.

Mum frowned in puzzlement and disbelief at my reaction. I had to tell her that compared to what I had been imagining all those years this seemed, well, not a lot to worry about. I think if it had happened to me I would have been angry, but if he had apologised I would have put it down to the demon drink, while still being careful of ever being alone with him. And of course, my dad had every right to be angry with his brother. But a lifelong vendetta, keeping grandparents and children apart? It doesn’t seem reasonable to me. However, I have lately wondered what did my mother mean by a ‘pass’? Defined in my dictionary as amorous or sexual advances, that can cover quite a range from the mildly flirtatious to the gross.

I hasten to add, in fairness to a man who cannot answer for himself from beyond the grave, that I have only ever heard my mother’s account of this incident, not my long deceased uncle’s. In any case, there were already existing tensions that this matter brought to a head. Mum just didn’t like her in-laws. No, that’s wrong. She loathed them. She saw Dad’s sister Sarah as schoolteachery and supercilious, and Patrick had put himself beyond the pale.

My mother was a pretty woman, with a heart-shaped face. She disliked having a slightly upturned nose, but when she read in some women’s magazine that this shape was called ‘retroussée’ she felt better about it. Her black hair fell easily into waves. With wearisome repetitiveness she told me year in year out that a woman’s crowning glory was her hair. When I was a wee girl and wanting to get out to play, mutinously fretting as she curled my hair with heated tongs, it would promptly revert to being straight as soon as I was outdoors in our damp climate. In my late teenage years, she told me that, with poker straight hair like mine, I would really spoil my chances of getting a boyfriend. When I pointed out that observation of couples in the street disproved this theory, she would sigh and say I was being irritatingly logical. Just like an O’Neill.

My parents were disgusted by Alexander McArthur’s novel,No Mean City, a bestseller that painted a dreadful picture of Glasgow, full of razor gangs, seedy sex scenes, and general squalor. Yet the reality of my parents’ and their neighbours’ lives was scrubbing the walls to make sure bugs were kept at bay, and taking turns to wash down the tenement stairs. The violence and criminal ongoings were simply not how those Catholic, Protestant and Jewish families lived. When youngsters of my brothers’ generation went out into the wider world, they met people who only knew of the Gorbals what they had read in that book, and it did damage to the city’s reputation – and its citizens’ job chances – that took decades to overcome.

Before her marriage, my mother had been the manager of a licensed grocer’s shop in the Gorbals, but she gave up work when she got married. It was considered a blow to a man’s pride if his wife worked. She even felt compelled to give up her membership of St John’s Church choir. She enjoyed singing – she was always singing about the house. But a married woman – even if she was not yet a mother – had to concentrate on her domestic duties and have no time for fripperies like singing in a choir. I am certain this notion did not come from any diktat of my dad’s. That wasn’t in his nature.

When she was a teenager her father bought her a second-hand accordion at The Barras (Glasgow’s famous street market) and she taught herself to play it. When she sang around the house it was more often Irish ballads than anything else. Songs from the music hall, like ‘She’s Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage’ are hard wired into my own memory, but when I heard her sing ‘If I Had a Talking Picture of You’ I was puzzled. Pictures hung on the wall didn’t talk. Mum thought this was hilarious, because of course the song was about ‘the talkies’ at the cinema.

During the Depression, before I was born, she and Dad had created a concert party they named ‘The Sunbeams’, when he was out of work for four years. Its members were the children of his local branch of the Knights of St Columba, a Catholic charitable organisation. They trained the kids to dance, sing and recite poetry, and the idea was they would perform free, but with a slap-up tea to follow, at fundraising events around greater Glasgow. The tea, of course, was a welcome incentive to cash-strapped families. One girl had a costume for every dance. Be it flamenco, Egyptian sand dance, Cossack, no matter how exotic, her indefatigable mother would run it up on her sewing machine. The sad thing was, her daughter had little talent, so my dad had to exercise great diplomacy while Mum, who could be a little too tactless, stayed out the way. I still have a photo of two of their star performers – Cox and Cusick – in their dancing outfits. Long after my parents gave this up men and women would stop my mother in the street, calling out ‘Auntie Peggy!’ and reminisce about their performances. If any of those artistes ever made it to the stage I’d love to know.

My dad had the good fortune during the Depression to get a part time job as hall keeper for the Knights, paying15s a week, not declared to the ‘Buroo’ (the unemployment bureau). The hall was used for weddings, funerals, and all sorts of celebrations, so there were often some leftovers to supplement the miserly dole money. Whenever, after the Depression was over, Dad was in funds he sometimes brought home a box of Black Magic chocolates for Mum. This was a standing family joke, because the first ever time he did so was when he broke the news he had been sacked. Mum was always suspicious of bad news when she saw this particular brand of chocs emerge from the brown paper bag.

My mother’s other notable talent was sewing. She often made outfits for me on her ancient black and gold second-hand table-top Singer sewing machine. She would push the material under the needle as it rose up and down again with her left hand while ‘ca’in the haunle’ (turning the handle manually) to control the speed with her right. If the material was very fine, and needed extra careful guidance underneath the needle, I was called upon to turn the handle gently and slowly. My other job was to thread the needle to get her going, as her own eyesight wasn’t up to it. Then there was the problem of comprehending the patterns, some of which were unbelievably complex. Lewis’s Polytechnic in Argyle Street, where Debenham’s now stands, had a large department devoted to the sale of dressmaking material and patterns for all kinds of clothes. I was always glad when she chose a Butterick pattern. I could understand their instructions. ButVogue– although ultra-fashionable – was usually beyond our collective wits. We were all baffled by the instruction in one such pattern to use tailors’ tacks. My mother asked for them in half a dozen different shops, and no-one had heard of them. Until one day, an assistant, who could hardly tell her for laughing, revealed that tailors’ tacks were simply long hand stitches used to hold the hem in place so that the machine stitching could be done more easily.

A sailor suit, made for me when I was four, was created despite these setbacks. I had the traditional sailor’s tunic with the squared-off collar hanging down at the back, a white lanyard hanging down my front, a navy blue accordion pleated skirt and a sailor’s cap set jauntily on my head, its band braided with the name of some Royal Navy shipHMSSomething-or-Other. She had seen the braid in the window of an armed forces’ outfitters in Jamaica Street, and fibbed that her husband was serving aboard that vessel. I liked my sailor suit a lot. The item I hated was my brown gabardine raincoat, which I deliberately left in the school cloakroom, in the hope of its being stolen by some other pupil. It was. No-one could have mistaken it for the usual shop-bought ‘utility’ raincoat, which were all identical. I suppose I was just uncomfortable at being different. But my mother was not going to have her handiwork lost so easily. She stood in wait at the school gates, caught the culprit, and had a few acerbic words with her mother before bringing her trophy home.

Clothes were rationed in1941, and your limit was66coupons in a year. Advertisements would show the price of the garment and the number of coupons needed: it was26for a man’s suit, three for children’s shoes. For many years my dad used a cobbler’s last, the better to grip a worn out shoe when he mended it with leather soles bought from Woolworths. As late as1949– four years after the war ended – my primary class was taught to darn the heels in socks and elbows in cardigans. We were even made to make ourselves a pair of knickers with a remnant of cotton and some elastic. The hems on girls’ dresses would be at least three or four inches, so that they could be let down as they grew.

My recollection of wartime food shortages is not a remembrance of deprivation. But one particular day sticks in my mind: the day my mother tried to get me to eat a boiled egg. Egg, in my experience, was a powder that came out of a cardboard box. With all the conservatism that children can display towards unknown foods, I resisted it. Mum was actually crying as she tried to persuade me to eat the egg because she was worried about my low growth rate, but this was maternal over-anxiety. I was bouncing with health. She met my refusal with the threat of the ‘jandies’, a terrible illness that would turn my skin yellow and stop me from running about and playing. It was years before I realised she was talking about jaundice. Finally, she won me over by mashing it with margarine in a teacup, one teaspoonful for my teddy bear, one for me, until it was done.

Rationing was introduced in1940. Meat of any kind available was limited to1s2d worth (around5.8pence now) for every person per week. At early1940s prices that would buy half a pound of mince.

Sweets had special coupons of their own at the back of the ration book. You got a mere six ounces every four weeks, and this scarcity lasted until1953. At least it kept caries at bay. Back then, if you couldn’t get any toothpaste, you put soot from the chimney on your toothbrush.

Shops were told to fix their prices in line with government guidelines, so that no-one would go hungry. A contrast to the First World War, when many shops fixed their prices so high that only the better off could afford to buy.

There was National Margarine in half pound blocks that came in a plain greaseproof paper wrapper – brand names did not exist. Butter came in a large mound from which the assistant would cut off a piece and, with the aid of wooden paddles, knock it into an approximate rectangular shape before wrapping it in greaseproof paper. If you wanted cheddar cheese the assistant would take a wire cutter to a large block and assess the exact place to cut to provide the desired amount.

Vegetables like carrots and potatoes were never seen in plastic packs but came loose and with the earth still sticking to them. Bacon was sliced to the thickness you required. Sugar was scooped into small paper bags. Items like potatoes were borne home in string bags. People held on to their supplies of paper and unpicked the knots in string. There were no plastic carrier bags. You had to queue to be served by a grocery assistant who fetched everything you wanted from the shelves behind. In those days there was no such thing as a trolley, the only aisle was in the church, there was no muzak and no-one had heard of a supermarket.

Chapter2

‘Yes! We Have No Bananas’

‘YES! WE HAVENo Bananas’ was a popular wartime song, expressing cheerful resignation to queuing for potatoes and having no imported fruit.

By the time I was four we had moved to a tenement in Govanhill Street, away from the Gorbals but still on the south side of the city. A big improvement. There were bright electric lights in the house – no more sputtering gas lamps – AND our own inside toilet. A large wooden bunker held the coal for the black leaded kitchen range.

At the bottom of our street was Cathcart Road, where my dad drove his tram from Langside Depot, a step away from the Victoria Infirmary. He would sometimes pop me on board and take me up and down his route. The trams in earlier days had simply been painted with a broad red, blue, green or white stripe from end to end of the upper deck according to their destination, but by that time, with the growth of the network, they had acquired numbers as well. Rouken Glen Park on the south side could be reached by tram, either from Riddrie in the east end or Gairbraid Avenue in faraway Maryhill, in the north-west of the city. If you were a south sider, Maryhill could have been on another planet, for all the likelihood of your ever going there. Little did I think in those childhood days that one day I would be theMPfor Maryhill.