Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Owen Sheehy Skeffington was one of the few Irish public figures who carried a flame for individual conscience and humanitarianism during the mid century. He came from a socialist-republican backround (his father, Francis, a pacifist, murdered in 1916; his mother, Hanna, a prominent suffragette), and was to dedicate his life to the defence of liberal values. In her biography, his wife chronicles his schooldays in Ireland and America, his career as teacher at Trinity College, Dublin and time as senator during the 1950s and 1960s; and, most especially, his struggles with authoritarianism in all its guises, from the clerical right to the Maoist left. In every available forum – classroom, lecture hall, senate floor, newspaper column – this controversialist championed freedom of thought and encouraged debate on then-closed topics such as education, law, politics and religious affairs. Skeff was perhaps best encapsulated by Sean O'Faolain, speaking at his funeral in 1970: 'He was one of the noblest and most complete men our country has ever produced, a man undefeated by all the weaklings and the cowards who yapped at him while he laughed and fought them, a man who, in a country and a time not rich in moral courage, never swerved or changed and who kept his youthful spirit to the very end. Such a man never leaves us.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 620

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

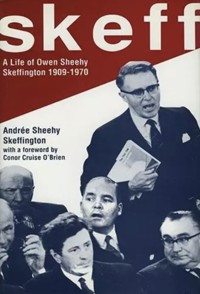

SKEFF

The Life of Owen Sheehy Skeffington 1909–1970

Andrée Sheehy Skeffington

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

Contents

TO FRANCIS, ALAN AND MICHELINE IN MEMORY OF THEIR FATHER

Foreword

Andrée’s life of Owen is a work of love, and of truth. The two values are not always found in alliance, but both are singularly appropriate to their subject. Owen’s whole career was motivated by love of the poor and helpless, and a commitment to freedom of expression, without which human beings cannot, in communication with one another, seek the truth. This love of the poor was fundamental to his concept of socialism – although he was acutely aware that much of what has passed for socialism in the twentieth century reflected a love of power rather than people. Owen’s commitment to freedom of expression – and his ample use of all the freedom he could find – got him into much more trouble than his socialism did. Socialism was an abstract condition, and one unlikely to prevail in a state whose basic ethos has been shaped by small farmers. Freedom of expression was something else.

Freedom of expression did exist in Ireland; in a sort of a way, and up to a point, which are conditions applicable to much of Irish life. Ireland was – and had inherited from the British the condition of being – a working political democracy. It was correctly understood that democracy entailed wide freedom of expression. But not all that wide. Ireland was a democracy, politically speaking. But at a deeper level, it was an authoritarian society, dominated by a hierarchy responsible to an individual who claimed to be God’s infallible representative on earth. These are not conditions easy to reconcile with freedom of expression, which must include freedom of dissent. The Catholic Church in Ireland, during most of Owen’s lifetime, did not include in its agenda, for the wide areas of his concern, anything corresponding to freedom of dissent.

The problem of combining political democracy with an essentially authoritarian religion and culture was solved in a characteristically adhoc and tacit way. The foundations were laid well before the Irish state came into being. As soon as mass democracy arrived in Ireland, under British rule, with the advent of universal adult male suffrage in the late nineteenth century, the representatives of the Catholic people in parliament demanded ‘denominational education’, at the bidding of the Catholic Church. The demand was largely conceded, and the Church was in control of the education of Catholics throughout Ireland by around the turn of the century.

Sinn Féin, when it won a majority of the seats in Catholic Ireland, might perhaps have been expected to challenge the arrangements set up by agreement between the Church and the British, but it refrained from doing so. Typically, the most significant appointment in the Cabinet set up by the First Dáil was a non-appointment. TherewasnoMinisterforEducation. All other Departments of State were to be taken over, in principle, but education was strictly left alone. During the revolution, as before, and after, the Church was left in charge of education.

In the new state, education became a taboo area, outside politics, and above them. The Church was in control, and the Church was not to be criticized. The actual workings of Irish democracy saw to that. The electorate was made up, more than 90 per cent, of practising Roman Catholics, most of whom had far more respect for the Church than for politicians (except perhaps some of the dead ones). So any challenge to the Church was politically dangerous in the extreme. Education was normally central to the taboo area, but there was in reality no domain to which the taboo could not be extended. The Church claimed infallibility, in moral as well as spiritual matters, and had the permanent advantage over the state, in that the Church, and the Church alone, could determine just where and when a moral issue arose.

It could arise in unexpected places. Thus, in 1951 – in circumstances described in this book – the hierarchy decided that a Mother-and-Child health scheme, without a means test, was contrary to the moral law. For believing Catholics, there was no defence against such a finding, and the government of the day fell as a result. For the most part, however, the areas of the Church’s concern appeared to be restricted to control of education and to questions of sexual morality: specifically, no divorce, no abortion (also, initially, no contraception).

Owen’s original contribution, which did much to change the character of Irish society, was to invade the taboo area, not on one or two isolated issues, but deliberately, repeatedly and with great effect. Except for some imaginative writers – whose books were banned by a Censorship of Publications established at the demand of the Catholic hierarchy – no one had done this before. Certainly no public representative had done it. Senator W. B. Yeats had indeed in 1925 spoken out, with fire and eloquence, against the prohibition of divorce. But that was an isolated episode. Owen’s method was to keep at it; to continue tapping away at the taboo area, to behave as if no taboo existed. Legally, this was quite in order, for the legal norms of the society included freedom of expression. There was a tacit understanding, however, that freedom of expression did not apply to matters on which the Catholic Church laid down the rules. Owen knew all about that tacit understanding, detested it, and persistently defied it. This took immense moral courage, in the Ireland of the mid-century and for some time thereafter, and Owen’s strength in that domain gradually overbore the more serious of his adversaries. That is what Sean O’Faolain meant when, in his beautiful eulogy at Owen’s graveside, he said: ‘Goodbye Owen. You won.’

That was true, in the sense that the taboo which Owen systematically broke, at no little cost to himself, began to crumble in his later years, and is no longer anything like as palpable as it was when Owen first challenged it. (As Andrée acknowledges, there were other more general forces at work, besides Owen’s influence, but to Owen belongs the credit of breaking the ice, and it took some breaking.) In public discourse – in parliament and in the media – the taboo has become so relaxed that you might think it had gone altogether. Though greatly weakened, it was still formidable around the time of Owen’s death. I remember a kind of benchmark episode, in the Dáil in 1970. The late Mícheál O Móráin, then Minister for Justice, was speaking on an Adoption Bill. Some deputies suggested certain changes but the minister would have none of them. He gave no reasons, only a warning metaphor: ‘There’s a stone wall, there.’ What he meant – as every deputy knew – was that the terms of the bill had been worked out in advance with representatives of the Catholic Church, whose rulings had been incorporated. A product of the implicit concordat between Church and State, the measure was not subject to parliamentary amendment, and the debate concerning it was no more than a formality. O Móráin’s bill was carried.

O Móráin, at the time of that episode, was an elderly man, and came from a part of the West of Ireland where stone walls – both in the material and metaphorical senses – were familiar and accepted objects. I don’t think any of his successors as Minister for Justice would have been likely to attempt to foreclose such a debate with such a metaphor – or that such an attempt, if made, would have succeeded.

Yet the stone walls – metaphorical as well as material – are still strong in rural Ireland. That was statistically evident in the referendums on divorce and abortion. The rural areas provided the two-thirds’ majorities for retaining the constitutional prohibition of any legislation permitting divorce and for inserting a new constitutional prohibition of any legislation permitting abortion. And of course these provisions are binding – at least in theory – on the citizens who voted against them, a majority in Dublin and the east coast.

The referendum figures are cold abstractions. Many of the social realities which underlie the majorities are veiled from view, but the kind of taboo which Owen succeeded in breaking, at the level of national debate, still prevails, as a kind of social miasma, covering certain areas of rural and small-town life (and perhaps some areas of city life as well). Just occasionally, that soft insidious mist lifts for a moment, to give a glimpse of horror too glaring to be altogether hushed up. One such case broke in the newspapers in the 1980s. It concerned a schoolgirl, in a small town in the Irish midlands. The girl was pregnant, but nobody noticed, or if they did they didn’t let on. She delivered her own baby, alone, at the foot of a statue of the Blessed Virgin. Mother and baby were there for some hours in the open before anyone came to help, and both died shortly afterwards.

I wrote about that episode at the time in an Irish newspaper. I made the obvious point that there seemed to be something badly wrong with Christianity, Irish-style, if a girl, in desperate need of help, could find none from any human being among those close to her – family, teachers, school companions, clergy – but was so brought up as to turn, in her extremity, to a lump of painted plaster. When my article appeared, a priest wrote to me, not angrily but in a tone of gentle remonstrance. I didn’t know all the circumstances, he said, and therefore should have been silent. He hinted that the girl’s father was also the father of her child and seemed to assume that once I had assimilated that fact – if fact it was – I would agree with him that the only thing to do was to hush the matter up and pretend it had never happened.

That episode, and the priest’s letter in particular, brought Owen’s memory forcibly to mind. The thought of that girl, and the social realities and pretences which destroyed her, made me understand better than before what Owen had been about. It clarified the link between his socialism and commitment to freedom of expression – a link which had not always been apparent to me. Owen’s socialism was essentially a love of the helpless; through freedom of expression he sought to help them, lifting the miasma of silence and taboo which protected their various exploiters and aggressors.

In stressing Owen’s commitment – as one must, since it was basic to his life and personality – one is in danger of making him sound like a prig, which he was not. Owen was, among other things, very funny. He abounded in both wit and humour: characteristics which often don’t go together. His humour was most evident in conversation with his friends. His wit was most evident in controversy, and it was his most effective weapon (examples will be found in this book). Irish people are alert to wit, and fear its application to themselves. Serious politicians learned not to tangle with him for much the same reason as chiefs, in medieval Ireland, tried to avoid tangling with bards, who might satirize them in a memorable and powerful fashion. Wit was important to Owen for another reason. He enjoyed the exercise, and it helped to keep his spirits up, bringing sustaining zest to controversies which, for anyone else, would have been wearing and distressing.

Owen was a born writer, and was most fulfilled in writing. This fact escaped the attention of his contemporaries because of the prevailing and erroneous assumption that a writer must write books. Like all good writers, Owen wrote exactly what he wanted to write, and not what someone else expected of him. He didn’t want to write books; he wanted to write letters. He wasn’t much interested either in the past or in posterity; he was interested in the here and now – in the fate of his contemporaries and in changing their minds. He was a kind of secular St Paul: a person with an urgent message, using the letter as his medium.

Academia, understandably, did not appreciate Owen at his real value. As his students knew, he was an excellent teacher, but he was too much of a teacher to achieve academic recognition. He did not set out to write books, not because of a lack of ability – far from it – but because of an inner knowledge that that would distract from his proper and urgent work. Though he published, in fact, a great deal, it did not rate as ‘publication’, in an academic sense.

There is a relevant story from American academia. Two centurions are trudging through the Judean desert, circaAD 34. One shows signs of distress and depression, and his companion asks him what the matter is.

*

I knew Owen all my life, at least for that long part of my conscious life which overlapped with his. We were first cousins and we were both only children. Owen, nine years older, was more like a brother than a cousin and – after my father’s death when I was ten years old – he was something like a father to me. I hope sometime, perhaps in memoirs of my own, to try to set down what Owen’s example and influence meant to me. But that would be a lengthy task, and this is not the place for it. Here it is enough to acknowledge that, although I thought I knew Owen pretty well, I have learned a great deal from Andrée’s lucid and thoughtful narrative.

There are other things too. Like most good writers of prose, Owen wrote as he talked. So as I read the extracts from his letters, I could hear his voice, and occasionally found myself wanting to talk back; not to argue, really, but to tell him things we neither of us knew when he was alive. Thus, when I read his generous but less than well-informed tribute to Pius XII – which he later retracted – I found myself wanting to tell him about Pius XI, who did indeed deserve such a tribute. Pius XI, in 1937, ordered the preparation by two Jesuits of an encyclical against racism and anti-Semitism. The encyclical was prepared, with the noble and most timely title, HumaniGenerisUnitas. Unfortunately, Pius XI died before he could promulgate the encyclical, and his successor, Pius XII, suppressed it for fear of offending the German government. I know Owen would have been interested in that episode, and glad to hear about Pius XI’s courageous effort. Owen liked to be able to think better of people, if he could at all, even – perhaps especially – if they were on the other side, in some basics. In that sense, he lacked the party spirit. He scored points with delight against ideas, and could be tough on crass expositions of ideas, but he was easier on his opponents, generally speaking, than most gifted controversialists are. I feel I understand Owen better thanks to this book. One of the things I see more clearly now is something of great importance in Owen’s life: his intellectual and moral relationship to the memory of his father, and to his mother; and, associated with these, his commitment to pacifism, and his evolving – and finally negative – attitude to militant Irish republicanism. This is a difficult and fraught area, and Andrée has explored it with respectful, restrained and illuminating subtlety.

I should like to end with the concept of illumination. Andrée mentions, in the envoi, that light which Owen lit for me when I was a child, frightened of the dark. As she rightly says, Owen would have rejected any suggestion of an allegory here. Yet for me, the allegory is inescapable. When, long afterwards, I came to learn about the great historical intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment, it brought an image of Owen dazzlingly to mind. I remembered the inexpressible relief with which I had seen him, in the simple act of lighting a bedroom gas-lamp which the elders had told him to leave unlit.

ConorCruiseO’Brien,Howth,January1991

Introduction

Owen Sheehy Skeffington was the son of Francis Skeffington, shot in 1916 by a British officer subsequently found guilty of murder but insane, and Hanna Sheehy, eldest daughter of David Sheehy, nationalist MP during the Parnell-Dillon era. Both were, at the beginning of the century, enthusiastic supporters of the cultural revival, yet had reservations about the drive for the restoration of the Irish language. They were friends of Connolly, Pearse, MacDonagh and Markievicz, but did not favour a military uprising. (Frank was an ardent pacifist.) They were lukewarm supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party, having helped to form the Young Ireland branch, but rebelled against John Redmond for his shelving of women’s suffrage. They were both feminists, Hanna being the leader of the militant wing of the suffragists and Frank the editor of TheIrishCitizen, its organ. They were socialists and internationalists. Shortly after their marriage they had left the Catholic Church. They were therefore thoroughly unorthodox in the ranks of patriots, in which both felt they belonged.

Although Frank was one of the first victims of 1916 at the hands of the British military, he never got the official crown of martyrdom, in spite of Sean O’Casey’s early insistence that he was one of the real martyrs of the Rising, ‘the Irish Gandhi’. Hanna’s struggles in the cause of women’s equality, her tragic widowhood, her active support and work for Sinn Féin and early Fianna Fáil won the respect of many but no official recognition, until the late 1970s, when she was ‘resurrected’ by the new Women’s Liberation Movement.

One may wonder what the only son of such remarkable parents was likely to become, in the emerging Free State of the 1920s and the next fifty years, during which the ideals of the early movements were to dwindle while the power of native money grew and the dominant Church became more deeply entrenched. When in 1916 Herbert Asquith, the British Prime Minister, offered Hanna a substantial financial compensation for the education of her fatherless son, she flatly turned it down. ‘But won’t your son reproach you when he grows up?’ Asquith demanded. ‘If he turns out that way, I wouldn’t care what he said,’ was her answer.

To what extent did Owen Sheehy Skeffington remain a 1916 orphan? To what extent did his mother in her thirty years of widowhood influence him? How did this background mould his personality?

Steeped at home from 1916 in a predominantly republican atmosphere, Owen grew into youth and manhood gradually working out his own understanding of those traumatic years. He tried to fulfil, in a discordant context, his father’s ideal of a socialist and liberal Ireland. In this he became a pioneer and forerunner, in a nation where the landslide caused by the revolution and Civil War had uncovered veins of bigotry and ruthlessness and given scope to materialism and lust for power. 1916 was a national tragedy in that Ireland lost some of its greatest leaders and the country became deeply divided. For Owen it was a personal tragedy, as well as creating a similar conflict of allegiance within himself. He was to resolve this inner conflict long before the nation began to heal its breaches.

ONE

Beginnings 1909–16

Owen’s parents had been six years married when he was born on 19 May 1909: the eve of Ascension Day, as Hanna noted in her diary. They had wanted a child and anticipated the birth with joy. Writing to his friend John Byrne on 26 April 1909, Frank Sheehy Skeffington describes the past months as ‘exceptionally full’ for him. He had gone through four months of illness, the ‘howl of execration by the clericals’ provoked by the publication of his controversial biography of Michael Davitt, and an extremely busy winter of political activity. On 16 April had come the severe shock of his mother’s death. A month later he reports another landmark: he had become a father. The baby’s birth, apparently long overdue, had been difficult. Serious complications followed and he had gone through a very anxious time for several weeks, with Hanna on the verge of death. She did not return home from the nursing home until the middle of June. However, although he confessed he felt that his youth was now definitely over, he was not oppressed by any spirit of regret. The relief that mother and son were now doing well and the happiness of fatherhood had wiped out smaller disappointments. He looked forward eagerly to his new responsibilities. ‘I can face every contingency, even death, with a smile on my lips.’ Prophetic words: he was not to see the seventh birthday of the son whose birth renewed his faith in, and his love of, life.

Hanna had been fully occupied in the months preceding the birth and had at least one teaching job, in Eccles Street convent. A year earlier, 1908, she had been one of the founders of the Irish Women’s Franchise League, the militant organization for women’s suffrage whose activities remained lawful for four years. Weekly open-air meetings were held in the Phoenix Park or at Foster or Beresford Place, the speaker standing on a portable wooden platform bearing a brass plate inscribed ‘Votes for Women’. The women picketed and heckled Irish Parliamentary Party meetings, demanding ‘Home Rule for Women’, or held parades displaying a green banner on which was embroidered in gold lettering on one side: ‘Irish Women’s Franchise League’, and on the other: ‘Cumannacht is Cóir Comhthruime na mBan’. These activities were interrupted about a month before the baby was born. She was so unwell that the possibility of death in childbirth crossed her mind and drove her to scribble a private ‘testament’ to Frank. Wanting to remove all feeling of guilt he might have, she assured him that she had taken up motherhood of her own ‘absolute free will and pleasure’, and had been happy in her decision and in her condition, in spite of illness. She had made her choice as a liberated feminist: and there was no room for regrets. She requested ‘no religious trappings’ were she to die, ‘and only real friends’, particularly women, at her funeral.

She had hoped for a daughter. Writing, in July 1909, to her French friend Germaine (herself just married), on a postcard replica of suffragette Christabel Pankhurst’s portrait, she says: ‘This is a symbolic card, for I am very sorry Owen isn’t a girl! I’d have liked the woman warrior type – Tant pis!’ Owen does not appear ever to have suffered from his mother’s initial disappointment. But he knew that she would have liked to have another child, probably in the hope of a daughter.

The names registered for the child were Owen Lancelot. ‘Owen’ was meant to be the equivalent of Eugene, Greek for ‘well-born’; Lancelot was after the Arthurian Lancelot du Lac. There was some semantic argument between Frank and his father about the meaning and derivation of the name Owen, Joseph Skeffington affirming that Owen was Eoin, and therefore John, and Frank retorting that the name he meant his son to have was ‘Eoghan’ or ‘Eugene’. But there was much more serious disagreement when it was revealed that the baby would not be baptized. Frank and Hanna, having ceased to believe in the Christian religion, decided not to start the child ‘on a false path’ (letter to William Moloney, 5 July 1909). Joseph Skeffington continued to express his distress about this for a long time. In a letter dated 1911 he writes:

I feel greatly grieved at the way he is being brought up – as a mere animal – without any development of the spiritual which is an essential element of humanity as distinguished from animality. He should learn Hymns, Prayers, stories of angels etc. – and be elevated above mere material thoughts.

Dr J.B. (as Frank’s father was often referred to) did not specifically blame Hanna for this unchristian upbringing, but he blamed her later for encouraging his son to break the law and for providing an example of violence. On the other hand, a schoolfriend of Hanna’s, Madge O’Sullivan, née Murphy, blamed Frank for turning Hanna from a gentle, soft-spoken woman to a harsh, unmannerly one. Some friends were more understanding about the decision not to christen the baby and admired the parents’ honesty.1 The dismay and disapproval, however, was shared by the Sheehy side of the family. It probably served to widen a rift which had started in February with ‘the Cruise O’Brien affair’: the parents’ opposition to the marriage of Kathleen Sheehy and Francis Cruise O’Brien, which had the approval of the Sheehy Skeffingtons.2 But family ties were not broken forever. The Sheehy Skeffingtons’ visits to the Sheehy parents at 2 Belvedere Place resumed on 1 January 1911 when Owen was introduced to his grandfather. Thereafter either parent used to bring him across town, by tram to Nelson’s Pillar. Barry’s Hotel in Great Denmark Street was another place to call at; Kate Barry was Hanna’s godmother.

Meanwhile, in June 1909, Owen was proving to be a ‘dear’ little man, as his father wrote. The bill from the nursing home in Lower Leeson Street (£21) was not paid for several months. The woman doctor (Hanna being true to her feminist principles) was still coming twice a week in June. ‘I don’t think I shall be able to meet these expenses unaided,’ Frank wrote to his father. No doubt Grandfather Skeffington came to the rescue in the end, as he usually did, grumblingly, but paternally. He could not forgive Frank’s feminist gesture in adding his wife’s name to his own. ‘You have practically given me up, and ranged yourself as a Sheehy – under which name (and not Skeffington) you appear in Thom’s Directory,’ he wrote in October 1911, suggesting that the Sheehys should be asked to help! Still, his love for his son got the upper hand.

Frank and Hanna, at this time, had no assured income. Frank’s earnings were precariously based on freelance journalism. He contributed to a great many papers, some of them short-lived: the Nationalist, the NationalDemocrat, the IrishPeasant,YoungIreland, the Freeman’sJournal, the ReviewofReviews; and was correspondent for English, French and American journals: the ManchesterGuardian,LondonHerald,NewYorkCall, and Jaurès’ L’Humanité.

Prior to his marriage he had been appointed the first lay registrar of UCD, but continued his feminist activities and propaganda, provoking the President of the College to remark that this was not fitting for a registrar. Accordingly, a year after his marriage, he resigned.

It was not the first time Frank had clashed with the college authorities about feminism. While still an undergraduate he had written an essay on ‘A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question’ for the college magazine StStephen’s, but publication was banned by the college censor. This was published in a pamphlet together with an essay, ‘The Day of the Rabblement’, by James Joyce, also rejected by StStephen’s, in October 1901. In his piece Frank pleads for full equality between men and women students in all facets of university life: at least seventy years ahead of his time.

It is surprising that, one year later, the college appointed him registrar nevertheless. Perhaps they thought he had sown his wild oats and would soon stop his foolish feminist militancy. He didn’t.

Hanna was never sure of regular permanent employment as a teacher after the birth of the child. It was one of the basic tenets of their agreement before marriage that she should be allowed to have a profession and be financially independent. This was part of her feminist emancipation, and also a fundamental feature of her character. Frank not only accepted this attitude, but agreed with it whole-heartedly. It was not, however, easy to implement. They were not endowed with riches at the start. Both Frank and Hanna came from middle-class families, but with rather different backgrounds.

The Sheehys were a Munster family. One branch had emigrated to France after the siege of Limerick in 1690, with other ‘wild geese’. Another branch boasted of a Fr Nicholas Sheehy, martyr-priest of Clonmel in 1766, when he was singled out by the Ascendancy as champion of the ‘Whiteboys’ during the Penal Laws, and hanged for an alleged murder, his grave at Shanrahan soon becoming a place of pilgrimage. Hanna’s grandfather, who owned a mill in Mallow, belonged to a third branch and was talked of as ‘a gentle saint’; early a widower, he had dreamt of becoming a Trappist monk and had hoped to give his two sons and one daughter to the Church. The boys, Eugene (born 1841) and David (born 1844, Hanna’s father), were sent to the Irish seminary in Paris in the early 1860s, so as to avoid the Maynooth oath of allegiance to the British Crown. When a cholera epidemic swept through Paris, Eugene sent David back to Mallow, where he became a close friend of William O’Brien, and joined the Fenians. He was nearly arrested and escaped to the USA, where he spent some years.3 In 1876, after his return, he met and married Bessie (Elizabeth) McCoy. Eugene was ordained and appointed curate at Kilmallock, Co. Limerick in 1880, and later parish priest at Bruree and Rockhill. Active in the agrarian and Home Rule agitation, he was imprisoned several times. Referring to his warm personality, Hanna often laughingly said that he should have married and David should have been the priest. He was very fond of his niece, who returned his affection. He encouraged her reading and studies, and his influence on Hanna was probably greater than her father’s.

For a priest, his mind seems to have been more independent from Church hierarchy than David’s. After a visit to Rome, to appeal to the Pope, successfully, against his bishop’s decision to suspend him because of his Land League activities, he had preached on Peter’s Pence a sermon entirely devoted to a description of Vatican pomp and display – with the result that few parishioners felt obliged to squeeze even a few pence from their meagre earnings. That was a story Hanna enjoyed telling and Owen enjoyed hearing. Fr Eugene was loved and admired by his Kilmallock parishioners for his ‘twofold character of priest and Irishman’, in the words of an illuminated address, headed with portraits of himself and Parnell, presented to him on his return from Kilmainham Jail in October 1882. In Bruree National School, he taught young Edward (Eamon) de Valera, who remembered him with gratitude when he sent Owen a photo of the school in 1957. De Valera also telephoned me on hearing of Owen’s death to express his deep regret and recall his long association with the family, from those days with Fr Sheehy to his association with Hanna when she was on the executive of Sinn Féin and joined Fianna Fáil, although he did not refer to her resignation from the party in 1927.

Hanna, christened Johanna, a name which she loathed, was born in Kanturk, Co. Cork, 24 May 1877, in the mill-house. When she was three her parents moved to another mill, in Loughmore, Co. Tipperary, ‘the hub of the Land War’, as she described it. There she had her first schooling. She was the eldest of six children – four girls and two boys: Hanna, Margaret, Mary, Richard, Eugene and Kathleen. Their father became a fervent follower of Parnell – up to the divorce case – then of Dillon. He had been elected an MP for the Irish Party in 1886, and the family moved to Dublin the following year, when Hanna was ten, first to Hollybank Road, Drumcondra, and later to 2 Belvedere Place. The girls attended the Dominican school in Eccles Street, the boys Belvedere College. All but one, Margaret, who took up dramatics, subsequently got degrees at the Catholic University, ‘the old Royal’, University College Dublin.

It was as a student that Hanna first saw and heard F.J.C. Skeffington, who entered university in 1896, one year after her. You couldn’t help noticing Skeffington. In spite of his small stature he stood out among his contemporaries, with his untrimmed reddish beard and moustache, his unconventional tweed knickerbockers, his high-pitched Northern voice; always challenging opinion, putting forward his own unorthodox ideas without fear of ridicule, stirring up people’s consciences at the risk of unpopularity. Francis Joseph Christopher Skeffington was born on 23 December 1878 in Bailieborough, Co. Cavan, of Northern Catholic stock. He was the only child of Dr Joseph Skeffington and Rose Magorian.

The Skeffington lineage is unclear. According to Leah Levenson (WithWoodenSword) one opinion is that Dr J.B. Skeffington’s father was a Joseph Skeffington, dealer, although a tombstone inscription in Downpatrick implies that it was a George Lindsay Skeffington, married to a Mary Murphy by whom he had eight children. On the other hand, among Hanna’s personal papers is a family tree, in her handwriting, naming Dr J.B.’s father as William and his mother as Mary Murphy, ‘née Lynch’, born in 1809. They also contain family photographs, including Mary Murphy as Dr J.B.’s mother, as well as small replicas of the Massarene and Skeffington family crests framed together, Hanna apparently believing in a family connection. Rose was forty years old when she married Skeffington, a man eighteen years younger and better educated than she was. She had been to the USA, following a family trend to emigrate for economic reasons, the hope being to save enough money to rescue the family farm. She must have been a woman of some character and independence. Her personality, however, remains shadowy and dominated by that of her husband. Her son, born when she was forty-nine years old, was fond of her but had very little in common with her. When she died, he confessed to a friend that ‘from every rational stand-point, one would feel that the marriage of my father and mother was a mistake; they were not in the least suited to one another’. Dr J.B. Skeffington, MA and LLD, was a District Inspector of National Schools from 1875, first in Bailieborough, later in Newtownards and Downpatrick, until he was appointed to the Waterford district in 1898 and promoted to Senior Inspector. He then transferred his household to Dublin at 24 Elm Grove, Ranelagh until his retirement in 1909. Rose died the same year, a month before their grandson, Owen, was born.

Joseph Skeffington remarried, and had a daughter, Anna, born 21 September 1914, by his second wife. Anna contacted Owen in the late 1950s and kept in touch with his family until her death in 1978. Other members of the Skeffington Magorian family who kept in some contact with Owen were the Grants from Downpatrick; Mrs John Grant (Marie Rose) was Rose’s niece. Another branch of the large Magorian family were the Mansons from Newcastle, Co. Down (Mary Manson contacted Owen in 1948). Owen had also visited great-aunts (he remembered Aunt Bella’s name) in Newcastle and Belfast with his father or mother. After Frank’s death in 1916 relations between Hanna and Owen and the Northern branches became necessarily more distant, except for Grandfather Skeffington’s personal interest in Owen. On one occasion, in the 1920s, Hanna, taking Owen to Belfast to visit an aunt, was arrested as a suspect Sinn Féiner and served with a deportation order. This was to be used against her in 1933 when she was arrested for defying the order and imprisoned in Armagh.

Owen’s Skeffington grandparents and Belfast great-aunts were of a Catholic nationalist tradition, without the Fenian rebellious streak of his Sheehy forbears, and with a certain narrowness and rigidity of attitude. When Rose Skeffington came to settle in Dublin, she asked Hanna to tell her which were the Catholic shops. Hanna couldn’t say. Dr J.B. apparently did not trust the education system he had to supervise, for he taught his son himself, up to university level. Frank later regretted this, not because he was badly taught – he described his father as ‘the best teacher I ever had’ and went on to win several distinctions in college – but because he had been isolated from his contemporaries. This gave him, on the other hand, a less institutionalized view of things. His father, unwittingly, may have helped to make a non-conformist of his son. Frank admired his father’s knowledge and his extensive reading,4 but father and son clashed on many topics, in particular the Irish language revival and women’s suffrage. Frank had been a feminist since the age of fifteen, when he had been greatly influenced by W. T. Stead’s writings on pacifism and feminism. His father thought the militant suffrage campaign an encouragement of law-breaking and a display of bad manners. He was, however, a keen Irish language revivalist, while Frank dismissed it as a side-issue.5

Frank was still a believing Catholic when he entered university, but ceased to be one after graduation. His letters to Hanna from Kilkenny, where he was teaching, expressed his unease and irritation at the current deference to the Catholic Church. Hanna held on to her faith a few years longer. She had at one time intended to become a nun, and, despite her advanced feminist views, she remained reserved and somewhat puritanical. She was attracted by Frank’s ebullience and love of life, his spirited attack on prejudices and his unconventionality. There must have been an instant spark of understanding between them – both fired with a strong sense of dedication, both by nature uncompromising on basic principles, both without worldly ambition.

Women were not admitted to the college at this time although they were allowed to prepare for the examinations of the Royal University. The intellectual give and take of university life was denied them, and this inequality of status was soon to be the first plank in Frank’s feminist platform. Partly, perhaps, because of this official segregation and constraint, the Sheehys’ Second Sundays at 2 Belvedere Place were very popular among the growing generation, including James Joyce, who had been at Belvedere College with Richard and Eugene Sheehy and was a frequent visitor up to 1905. Skeffington and Joyce met also at UCD and Joyce portrayed Skeffington as McCann in StephenHero. The Sheehys were a very political household, but most of the Second Sunday visitors were university friends, and evenings filled with parlour games, short plays, singing, recitations and charades, were characterized by satire and gaiety. The Second Sundays were presided over with quiet dignity by Mrs Sheehy, whose motherly presence put everybody at ease. One of the most popular forms of entertainment was the acting of charades, in which the guests were involved in turn. According to Willie Moloney, Skeffington and Joyce were the wittiest of performers. The latter, he recalled in a letter to Owen, ‘had a look of settled sadness, but your father was always full of mirth’. Joyce has immortalized these gatherings in StephenHero and APortraitoftheArtist. This improvised acting game inspired a playlet, ‘Cupid’s Confidante’, written by Hanna and produced by Margaret, with Joyce playing the part of the villain.6

Frank and Hanna had been engaged for a year when Frank seized an opportunity to ask Hanna’s father for her hand. He wrote a description of the scene in a letter to Hanna, who was then an ‘au pair’ with a family in Paris. The scene was the Bective football ground at Ballsbridge.

I decided to plunge at once. I was very nervous – physically. But it passed into my legs, which trembled violently under me (it was a cold day!); and I managed to keep both my voice and my face cool. ‘Now that I have the opportunity of speaking to you alone,’ said I, ‘I want to speak to you about something of a private nature, but I must ask you to undertake to keep it entirely between ourselves.’ ‘All right,’ said he, with a dawning light already in his eyes. We were both manoeuvring a little with our feet now, each trying to get the setting sun full in the other’s face and neither quite succeeding. I went on, very steadily and coolly. ‘I want to ask you if you would consent to an engagement between Hanna and myself?’ Without showing any surprise, he answered gravely, ‘I assure you, Skeffington, I’d be very happy.’ Well, I said something like ‘then, that’s all’, and we shook hands. He went on, ‘I don’t know any young man that I’d sooner have for my son-in-law than you. I believe you have such qualities as will make her happy; and her happiness is the only question with me.’ Then I went back and watched the match.

No future disagreement between the parents and the young couple could have been very serious or lasting with that basis of affection and understanding.

They were married in June 1903 in the University Church, in a brief Catholic ceremony. Their unconventional honeymoon was a cycling trip round the south of Ireland, the bicycle being a token of women’s emancipation at the time. They lived first in a little house at 8 Airfield Road, Rathgar – a rather pro-British area – deserting the north side of Dublin around Mountjoy Square, which had been the haunt of the Sheehys and many nationalists. A year before Owen was born they moved to a slightly bigger house at 11 (now 21) Grosvenor Place, Rathmines, in the same area – a modest, red-brick Victorian terraced house with a small front garden. As Frank was down the country, recuperating after a bout of diphtheria, Hanna had to deal with the move alone.

Theirs was a true union of hearts and minds, but with each at all times respecting the other’s freedom. They seemed to be inseparable, while being conscious of each other’s individual rights. It was agreed in particular that Hanna should not be confined to ‘the tyranny of pots and pans’, as she put it, but should have a job if she so chose. She got small teaching jobs until she was employed on a more permanent basis in Rathmines Technical School. She did not like to be dependent on Frank and fretted at having to use his money. It became more difficult to obtain a permanent teaching job after Owen’s birth, and later after her suffrage militancy. Both she and Frank often took separate holidays, sometimes going to summer schools abroad. Hanna continued to do this even after Owen was born, leaving Frank in charge. They had a common cause to fight for in the women’s suffrage movement, particularly from 1908, when they founded the militant Irish Women’s Franchise League with James and Margaret Cousins. Four years later, with the start of active militancy and the foundation of a suffrage paper, TheIrishCitizen,7 their lives became dedicated to the cause of women, the answer to Frank’s hope expressed in a letter to Hanna in November 1900, on the anniversary of their betrothal. He reminded her of their hill climbs during those days of happiness: ‘emblems of what our life shall be; always making onward towards some highest point, always exultant even when struggling’. This was very far from the grandfather’s imagined ‘material thoughts’.

Frank and Hanna’s dedication to causes outside the home did not make them neglectful of their child. They were very attentive parents and much concerned with his development. Frank seems to have been the more anxious of the two from the start, and the stricter. Before Owen was two months old, he began a diary of his progress, which he continued until Owen was two years and eight months – ‘a biography as well as an educational narrative’.8 Watching eagerly for any sign of character and intelligence, he judges the two-year-old boy ‘cowardly and cautious in physical matters, bold and aggressive in temper – just like myself.’ This would appear a surprisingly unfair verdict on both. But letters to Hanna reveal that Frank had in his boyhood flashes of ‘utterly unreasonable’ temper which still occurred occasionally up to his marriage. He would then write to Hanna in abject humiliation and repentance for these outbursts of a temperament which he thought he had subdued. His son may have inherited some of this ‘Skeffington passion’ (Hanna’s words), but controlled it better and earlier. On the other hand Frank notes with pleasure that, at two and a half, Owen had more knowledge of colours and numbers, more power of concentration and more control than his cousin Patricia – two or three months older.9 Frank believed in mild corporal punishment for children up to the age of seven, on the grounds that children are young animals up to that age. Hanna did not approve, but she too expected obedience.

Hanna sometimes said that Frank was too hard on the young child: ‘I am trying to present to him an attitude of calm, unbending justice!’ Frank writes, not without a spark of humour against himself. More pathetically, he says of Hanna: ‘She is the final court of appeal and is more beloved, as she wishes to be. I don’t mind so long as I am respected.’ On 23 December 1911 he writes in his diary: ‘Hanna says he has a sweet disposition. I doubt it! His face, especially his broad-based nose, just reminds me of my father’s mother – a masterful old lady truly.’

The general verdict was that Owen was ‘a very quaint kid’, by which people meant that he was a rather precocious child. At the age of five he solemnly proclaimed to his mother: ‘You are not perfect, and Daddy is not perfect, but I am nearly, and my little boy will be quite perfect.’ He was initiated early into his parents’ busy lives and was exposed to strong feminist attitudes and ideas. He was allowed to sit with either of them at work reading or writing, so long as he kept quiet – quite an ordeal of frustration sometimes, which had often to be alleviated with the promise, always kept, of a story; his father improving the shining hour by asking him later to tell the story as he remembered it. Frank always believed in stretching the child’s mental capacity. The majority of friends and most frequent visitors at 11 Grosvenor Place were ardent suffragists. Among them Hanna was to form a few of her most enduring friendships. Some took a particular interest in the young child: the Webbs10 (Josephine and Deborah), who lived close by, ‘Con’ and Meg Connery, the Wilkinses, and Rosamund Jacob, who lived in Waterford but often came up for meetings. Rose gives a glimpse of the household in a letter to Deborah Webb: ‘From what I have seen of 11 Grosvenor Place I should say there is no limit to the amount of papers and books that might be temporarily or permanently lost there [one of her MSS had been mislaid]. It is one mass of books and papers all over the ground floor, and I believe there is another room full upstairs’ (letter of 27 May 1914).

Owen’s playmates at that time included Robin Dudley Edwards, later Professor of History at UCD, who lived nearby.

Owen was not yet three when he was taken to a Franchise Fête. But an experience which left a more lasting mark was his visit, with his father, to Hanna in Mountjoy Jail, in the summer of 1912. The Irish Women’s Franchise League, united with other women’s groups in the demand for equal recognition of Irish women as citizens in the proposed Home Rule Bill, saw itself being totally ignored by the government and the Irish Party. As a result they resorted to militancy and eight volunteers smashed windows in government buildings. Hanna was one of them, having chosen Dublin Castle for her target. Like all the others, she refused to pay the fine and got two months’ imprisonment. Years later, Owen recalled his feelings of astonishment that wardresses, who were keeping his mother there against her will, could actually be nice to him and even give him chocolate. He learnt there that a jail sentence could be a matter of pride rather than shame, and that defiance of the law was not necessarily reprehensible.

Owen’s formal education began about that time. Both parents were agreed on the choice of school although it was Frank who took the final step. They deliberately avoided Pearse’s school, St Enda’s, then in Rathmines, in spite of its new methods and nationalist atmosphere. For one thing, it specifically catered for Catholic boys. It also laid more stress on the Irish language than Owen’s parents favoured. They wanted as near a non-denominational school as could be found, preferably a co-educational one. Through their friendship with the Webbs, they knew of the Quaker school, Rathgar Kindergarten and Training College, a few minutes’ walk from their home, at 11 Frankfort Avenue on the corner of Maxwell Road.

Owen was three and a half when, in January 1913, his father took him to see the school and its headmistress, Miss Isabella Tuckey. Frank had missed the companionship and social education of school, and was determined that Owen should not be similarly deprived. ‘If I see any sign of this child learning anything, I shall take him away at once,’ he said to the startled headmistress, explaining that his intention in bringing so young a subject was to have him learn how to live with other youngsters, not to make an infant prodigy of him. Miss Tuckey understood. She had taken over the school from Gertrude Webb, who had been one of the pioneers of Froebel education in Ireland. The Sheehy Skeffingtons subscribed to the idea, new then, that education is not all book-learning, manual work and play being every bit as necessary.

There were only about thirty pupils at the school when Owen joined it, as one of the youngest. It was still patronized largely but not exclusively by Quakers, and Owen’s first friends included children with names such as Bewley, Brooks, Douglas, Johnson, Webb, as well as Barrett, Bryson, Lambert. Apart from the reading of Bible stories no formal religious instruction was given, although a hymn was sung at ‘Opening’ every morning. The children’s occupations were planned to encourage freedom of expression and the development of observation and imagination, in singing, painting, woodwork, gardening, dancing and acting. Miss Tuckey was sympathetic to the Gaelic revival, and at story-time (the highlight of the day) Irish sagas alternated with, for instance, TheWaterBabies. The children also acted in short plays in English, Irish and French, the last spoken with much enthusiasm and less accuracy of accent. A sense of responsibility and co-operation was encouraged by the sharing of jobs among boys and girls.11 It was a happy place, especially for an only child, and Owen remembered it later for our own children.

He was just over five in August 1914 when his father brought out an IrishCitizen poster with the slogan: ‘Damn your war’. Frank, the militant pacifist, had stuck it on the gatepost of their house at 11 Grosvenor Place. It had been torn down. This was in a largely unionist area where such sentiments were not popular. Undaunted, Frank put up another, and brought Owen to stand outside and warn him of any attack on it. Owen describes this incident in family memoirs he wrote in 1961:

I remember standing beside the poster, rather frightened … Shortly later I saw a man emerging from the house opposite (he was said to be a colonel in the British Army) armed with a golf club. I can see him still … I remember him taking me gently but firmly by the arm and pushing me aside. He then proceeded to rip the poster with slashes of the golf club …

Owen remembered his duty too late; the colonel had retreated when his father dashed out, hoping to argue with him.

Owen also remembered being given a few months later the task of selling copies of TheIrishCitizen at some of his father’s anti-conscription meetings at Beresford Place.

After a few months of anti-conscription propaganda, Frank was arrested at the end of May 1915. It was Hanna’s turn to take Owen to see his father in Mountjoy. Owen was ‘almost as empressé as for the Zoo’, she notes. In his first letter from prison Frank had written: ‘Owen should be proud – few boys of six have had both parents in jail for freedom.’12 The meaning of this may have gone over Owen’s head at the time, but what left an indelible picture in his mind was his father’s return home after a hunger and thirst strike: a pale shadow of himself, he had to be helped up the path to the house by the cabby, and could just say in a barely audible whisper, ‘Hello, laddie.’ He had refused food and drink for nine days, in protest against his sentence: six months’ hard labour plus six months in default of bail. He claimed to have done no more than British opposition speakers.

In the autumn, after a brief holiday in Wales with Hanna and Owen, Frank went on a lecture tour to the USA.13 ‘No Dada to torment me now … We’ll be lonely for a little while …’ Owen remarked to his mother. A year later, events provoked a marked change in Owen’s image of his father.

Meanwhile Hanna had to cope on her own in Dublin. She and Frank wrote almost daily to each other, he encouraging her in her task of deputy editor of the IrishCitizen and telling her about all his meetings, she reporting progress and giving news of Owen.14 Owen was being difficult and Frank gave disciplinary advice, often disagreeing with Hanna’s methods.

Frank’s father, Dr J.B., tried hard to persuade his son to stay in America and bring his family over. He blamed Hanna for setting a bad example with her suffragette activities and hunger-strike. This feminist weapon was indeed to be used, as Hanna once remarked, by generations of protesters in other fields. Dr J.B. feared of course that Frank would be rearrested on landing in Ireland, since he had been released under the Cat and Mouse Act.15 But Frank was not going to run away: his whole life was for Ireland in Ireland, he had to be at the heart of things. A pacifist because he abhorred bloodshed for any cause, he was ever a militant in spirit: he once described as ‘glorious’ the prospect of having to fight many difficulties to establish a branch of the United Irish League in the largely unionist district of Rathmines.

He returned to Dublin, via Liverpool, just in time for Christmas 1915. He was not rearrested. Owen was thrilled, all the more so because his father brought back exciting American presents, including a magic lantern. But after Christmas the pace of events quickened. By St Patrick’s Day a sense of foreboding had invaded the Skeffington home which cannot have escaped the child’s perception.

Then came Easter Monday, smashing the holiday atmosphere. The following days are part of Irish history.16 The noise of shots and rumours of looting meant little to the young boy. His parents went out together and returned separately. This was nothing new. A maid looked after Owen when they were both out. What was more unusual was when his father did not return to tea one day. Owen himself gave an account of what happened when interviewed by the American socialist newspaper TheCall (6 January 1917):

The first thing we heard on Friday night, after my mother had returned from Dublin where she had gone to look for Daddy, was the firing of a volley of shots at our house. The maid was putting me to bed then, and mother rushed into the room to see what was happening. The maid picked me up and ran out into the back yard with me. Then mother came running after us. She told us to come back into the house, and said that the whole house must be surrounded and that we would be killed if we tried to escape.

I don’t like to be killed by soldiers, I want to die by myself.

After I was brought into the house by the maid, I heard a crash of glass, and then saw the soldiers with fixed bayonets climbing in through the windows … They told me to hold up my hands. They told the same thing to my mother and the maid. Then they rushed downstairs and broke my daddy’s desk, and took a lot of papers and other things …

What do you think they did to our bread? They stuck candles in all the loaves of bread in the house … They pulled down all my pictures from the walls and broke a lot of my toys … and I thought for several days they were going to kill my mother and me …

My daddy promised to take me to the museum as an Easter gift, and my mother was to take me to the theatre. My mother took me to the motion pictures theatre the day Daddy left for Dublin, but Daddy never took me to the museum. Daddy never came back to take me there.

Such were some of Owen’s vivid memories and impressions of that day. His father had been shot without trial, together with two other journalists, on the Wednesday morning of Easter week, in Portobello (now Cathal Brugha) Barracks, Rathmines. He had been arrested on the Tuesday, as he was walking home from Westmoreland Chambers (the Irish Women’s Franchise League headquarters), where he had waited, in vain, for volunteers to help him stop the looting of shops in town. Hanna knew nothing of his fate for several days. The raid on their house remembered by Owen was carried out on the Friday of that week by the officer guilty of the murder, Captain Bowen Colthurst, looking for proof of the guilt of the man he had shot. Among the papers he collected to serve as evidence was a two-page drawing by Owen, aged seven, showing on one side a zeppelin bearing flags with vertical red, white and black stripes, dropping similarly beflagged bombs on a ship; and on the other side a ship being bombed by an aeroplane, both plane and bombs bearing British flags. Apparently these drawings were deemed by the captain to be damning evidence of sympathy with the Germans: they are inscribed in the corner, ‘I certify that this was found in Skeffington’s House’, signed ‘J.C. Bowen Colthurst, Captain’ and dated 28/4/16. This and a few personal papers were returned to Hanna.

The agony of those days inflicted a deep wound on Owen’s mother which never really healed, and instilled in Owen a hatred of the military and of militarism. But from now on he was going to be, at least until adulthood, his mother’s son. Through her he gradually learnt more about his father. He was naturally influenced by her own reactions to the tragedy, which made her more of a Sinn Féiner than she had ever been. She did not try to indoctrinate him, and in later years he often paid tribute to her deliberate detachment and desire to let him develop his own personality.17 Still suffering from the shock of Frank’s death, she sat and wrote a testament bequeathing all she had to Owen, adding a wish more important to her than any material legacy:

In accordance with his father’s express wishes I do not desire to have him [Owen] brought up in any formal religious creed and I desire that steps should be taken by my executors so that during his school and college life he may receive only secular instruction. In general I rely on my executors in whom I have complete confidence to bring up my son as his father and I would have wished.18