13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

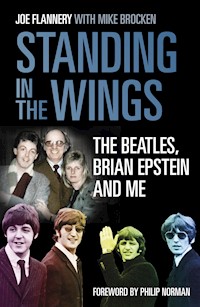

Joe Flannery has been described as the 'Secret Beatle', and as the business associate and partner of Brian Epstein, he became an integral part of The Beatles' management team during their rise to fame in the early 1960s.Standing in the Wings is Flannery's account of this fascinating era, which included the controversial dismissal of Pete Best from the group (nothing to do with London, but matters back in Liverpool), Brian Epstein's fragility, and the importance of the Star Club in Hamburg. This book is not simply a biography, as it also considers issues to do with sexuality in 1950s Liverpool, the vagaries of the music business at that time and the hazards of personal management in the 'swinging sixties'. At its heart, Standing in the Wings provides an in-depth look at Flannery's personal and professional relationship with Epstein and his close links with the Fab Four. Shortly before John Lennon's murder in 1980, it was Flannery who was one of the last people in the UK to talk to the great man. Indeed, Flannery remains one of the few 'Beatle people' in Liverpool to have the respect of the surviving Beatles, and this is reflected in this timely and revealing book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

I dedicate this book to my beloved city of Liverpool.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Foreword

Introduction

1 Early Childhood

2 Ivor Novello’s Poodles

3 A Dutiful Engagement and National Service

4 One or Two Home Truths

5 ‘Don’t worry Mr Loss, I won’t let you down’

6 The Life of Brian plus Teenage Rebels and Further Detours

7 Jack Good, Lee Curtis and Even More Detours

8 The Beatles at Gardner Road, Brian Epstein and Merseybeat

9 The Beginning of the Parting of the Ways and the Pete Best Affair

10 The Very Root of Meaning

11 Germany Calling

12 Liverbirds in Love: The Decline and Fall of Carlton Brooke

13 This is the End, Beautiful Friend

Postscript:‘Excuse me, Mr Lennon, a Mr Flannery’s on the phone’

Appendix:A Mayfield Records Discography

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD BY PHILIP NORMAN

IN 1979, AS I was embarking on my Beatles biography Shout!, I asked Bill Harry, John Lennon’s fellow art student and founder of Mersey Beat, to suggest interviewees who might give me a fresh perspective on a story everyone thought they knew. ‘Why don’t you talk to Joe Flannery,’ he replied. A couple of weeks later, I knocked on the front door of a neat 1920s house in Aigburth, Liverpool, and was greeted by a tall, quietly spoken man whose name appeared in none of the Beatles reference books then available. Biographers, especially in the rock music area, depend greatly on luck: that was one of my luckiest days ever.

Joe Flannery’s perspective was fresh indeed. His cabinet-maker father, Christopher, used to supply custom-built chests-of-drawers to Harry Epstein, the Liverpool furniture dealer, whose older son, Brian, would one day manage the most beloved pop band of all time. Joe had met Brian – and already fallen more than a little in love with him – when they were children. Both grew up to be gay in an era when homosexuality was outlawed in Britain and particularly anathematised in macho northern cities like Liverpool. With Joe, Brian had his only happy, stable relationship in a love life otherwise shadowed by fear, guilt, violence and disgrace.

The two lost touch for a few years, then met up again in 1962, by which time Brian was running the record department at his family’s central Liverpool electrical store. As a side-line, he had decided to manage a black leather-clad ‘beat group’ called the Beatles who, he insisted – to general mockery – would one day be ‘bigger than Elvis’. Dapper, well-spoken Brian, however, had no idea how to talk to the tough Merseyside dance promoters who were the Beatles’ main employers. So Joe volunteered to handle their bookings, and also made his house a base-camp for them after late-night gigs when it was too late to return to their respective homes. As a result, he could tell me Beatles stories that no one had ever heard before: of John (who always called him ‘Flo Jannery’) lying on the rug in front of his living-room fire, turning out endless drawings and poems; of Paul, asking him for guidance on social etiquette rather like Pip in Dickens’ Great Expectations; of giving George driving lessons in his car in the dawn hours while the others were asleep.

He also proved fascinatingly authoritative about the band’s mythic pre-Epstein period, with their pre-Ringo drummer Pete Best, playing drunken all-night shows among the strip-clubs and mud-wrestling pits of Hamburg’s red-light district, the Reeperbahn. He’d later gone out to Hamburg himself, acting as a kind of den-mother to other Liverpool bands like Lee Curtis and the All Stars, whose vocalist was his younger brother. Under his tutelage, I spent a week on the Reeperbahn, drinking the same beer and eating the same German hotdogs that the Beatles once had, and popping the same ‘uppers’ to be able to stay awake all night.

Brian had died of a drink-and-drugs overdose in 1967 – prefiguring the Beatles’ drawn-out, messy collapse – but to one person, at least, he’d never been forgotten. Each year on his birthday, Liverpool’s Long Lane synagogue gave Catholic Joe special permission to break with Jewish custom and place flowers on his grave.

As we became friends, Joe told me about the hellishness of being gay in 1950s Liverpool, even if one didn’t take the horrendous risks Brian did. He related blood-chilling stories of the ‘queer-bashing’ gangs that used to roam the streets; of the eminent citizens who preyed on gay young men with impunity in the backs of their Rolls-Royces; of the homophobia of police, the judicial system and, worst of all, one’s own family. His father never came to terms with Joe’s sexuality – though his wonderful, doughty mother, Agnes, shielded him from the worst of Christopher’s brutality. At one heartbreaking moment, Joe tried to express his love for his father by buying him a record, Eddie Calvert’s O mein Papa. ‘O mein Papa’, the lyric runs, ‘to me he was so wonderful/O Mein papa, to me he was so good ...’ Christopher took one look at the old-fashioned shellac disc, then broke it over Joe’s head.

There were other, happier stories, too, from the long ages before the world had heard of John, Paul, George and Ringo: of growing up in the next street to the crooner Frankie Vaughan; of working as a waiter at Liverpool’s Adelphi Hotel in its glory days, when Joe often found himself serving Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother: of his latter long, happy relationship with a sweet man named Kenny Meek, and his artists’ management partnership with Brian Epstein’s younger brother, Clive, who bore just enough of a resemblance to Brian to ensure that Joe’s love never died.

There was the phone conversation he had with John Lennon in New York, shortly before the fateful night of 8 December 1980, when John talked about making a triumphal return to Liverpool and asked ‘Flo Jannery’ to hire the QE2 to bring him up the Mersey. And there was always the Flannery humour, permeating even moments of greatest stress or sadness. After John’s murder, he wrote a tribute song entitled Much-Missed Man, which was to be recorded in Liverpool by one of his new young protégés, Phil Boardman. On the day of the session, typically, Joe drove to the studio with a red carnation for Phil’s buttonhole. As he told me at the time: ‘You know how much my religion means to me – but if a Catholic nun had been thumbing a lift into town, I wouldn’t have stopped because it’d have meant moving that carnation I’d arranged so carefully on the seat beside me.’

For years, I’ve been urging this dear, modest man to claim his rightful niche in pop music with a book ‘about the Beatles but not all about the Beatles’. I’m delighted he’s now done so.

INTRODUCTION BY JOE ANDERSON, MAYOR OF LIVERPOOL

IT ISN’T AN exaggeration to say that without Brian Epstein, the Beatles we know and love today wouldn’t exist. The former Beatles’ manager helped shape the musical landscape of the city, guiding the Fab Four from being a popular cellar act to global superstardom.

As a city, we want to make sure the legacy of one of Liverpool’s greatest sons continues, and it was a real honour when Brian’s family gave us permission to rename the Neptune Theatre to The Epstein – signalling a new chapter for the refurbished music venue which will hopefully discover the next generation of outstanding musical talent in the city.

This book by Joe Flannery sheds new light on the Epstein story, providing some previously unheard anecdotes about the man referred to as the ‘Prince of Pop’ – a man who changed the face of the music industry forever and, as a result, put Liverpool firmly on the map as a city overflowing with culture and creativity.

1

EARLY CHILDHOOD: ‘IF YOU DON’T KICK A FOOTBALL, YOU’LL GET YOUR HEAD KICKED-IN’

THE FLANNERYS CAME to Liverpool, via Cornwall, from Ireland. They were peasants from the rural area just west of Dublin and came to England to escape the potato famine of 1845. Land was in short supply in Ireland at this time and this family, like many others, grew what they could to sustain themselves on insufficient and meagre soil. My great-grandfather was one of nine children and his parents originally had about 2 acres of farmland; however, they had decided to let 1 acre of it go because a good potato crop could sustain even a large family on only 1 acre. There would always be spuds, it seemed, and it didn’t give the impression that it was worth the rent to farm 2 acres. Potatoes were the staple crop in Ireland at this time and it has been estimated that at least 4 million out of a total population of 8.5 million could, like the Flannerys, afford little else. But by the summer of 1845 potato blight had already appeared in England and by the autumn it had spread to Ireland; catastrophe ensued. Thousands starved to death, and the Flannerys gave up all they had – which was probably very little in the first place – and, along with countless others, decided to leave Ireland once and for all. The rural working classes in Ireland were faced with a very simple choice: stay and starve or leave and begin again. The Flannery family chose the latter and after initially trying their luck in the south-west of England in tin mining and fishing, they eventually ended up, along with many others of their kind, in the seaport of Liverpool.

By this time Liverpool was England’s second city, unimaginably wealthy via trade and commerce (which included slavery up to the beginning of the nineteenth century); yet, not even a mile from the commercial heartland of the city could be found the densely overpopulated Scotland Road and Byrom Street districts. It was here that the vast majority of Irish immigrants were forced to live … ‘live’? Survive, more like, for dumped as they were amid the squalor, rats and degradation of Liverpool’s infamous courtyard dwelling houses, they struggled to keep their heads above water in this city built on capital; they survived, but little else. A drab and dreary lack of choice seemingly followed them around; Irish and Catholic meant Scotland Road, docks and rats – it was pretty much as simple as that in a city that, one might argue, contributed to the destruction not creation of society. By the 1850s almost one-third of Britons lived in cities like Liverpool. What kind of places these actually were can only be estimated by our vivid imaginations. Smoke and filth dominated paltry water supplies and sanitation, street cleaning and open spaces, and epidemics of cholera and typhoid (together with respiratory and internal diseases) considerably shortened people’s often miserable lives.

My father, at least on the surface, appears to be a typical example of a working-class Liverpudlian: second-generation, poverty-stricken, regional Irish gradually making some kind of cultural space for himself. But it was far more complicated than such class-based visages allow. By the time the twentieth century had dawned he was actually suffering at the hands of an immigrant-based class system that had evolved within the Liverpool-Irish communities. In order to survive in such a city, working-class immigrants were forced to create their own echelon systems. Pre-industrial experiences, traditions, wisdom, and to a degree moralities were no adequate guide to living as an immigrant in an urban environment such as in Liverpool but, as with the equally diasporic Italian communities, they were used as marks of authenticity, thus rank. Material incentives were often determined by one’s so-called ‘Irish’ heritage and class while still in the ‘old country’. As a consequence the Flannerys were considered in Liverpool to be rather low-class Irish, even by their own immigrant community’s criteria. This had little to do with religion per se (that particular war raged essentially as an inter-district conflict), but more to do with the previous status of families back in Ireland.

So, as far as the Flannery side of my family was concerned, they appeared to possess very little kudos because of their rather rural hinterland background, and this increased the fragility of their social and economic position. Urbanity stretched to Dublin, it seemed, but not to its bucolic surroundings. Thus, although the Scotland Exchange political district of North Liverpool (where they were based) was fiercely Irish and regularly returned Irish Nationalist MPs for many years, this sense of Irishness and Irish nationalism was not cohesive and certainly not without its class echelons: hardly the ‘united’ district of Liverpool that local historians often spuriously claim it to be. How could it be? To deliberately misquote the great British industrial historian Eric Hobsbawm, if the immigrant Irishman in Liverpool earned more than the pittance he regarded as sufficient, he might indeed take it out in leisure, parties and alcohol, but he might also consider such financial extras as providing ways and means of rising through the ranks of his immigrant-based stratum. While Hobsbawm presumes that ignorance and thus poverty was all-pervading via these economic realities, he neglects how important money and influence could be. To have succeeded in the Liverpool of the early to mid-twentieth century, even as a second-generation Irish immigrant, was technically very difficult, but not impossible. If a rural or regional Irish background militated against progress, one way of jumping such hurdles lay within contacts: not necessarily exclusively from one’s own community (especially if it appeared to lack cohesion), but rather from other diasporic communities, such, as in my father, Chris Flannery’s, case, Jewish migrants. Rationality was required to come to the fore to understand the vagaries of trade across migrant communities; if it did and one possessed a skill (my father was a time-served joiner) progression was possible.

My mother’s family, the Mottrams, were also Irish Catholics but from County Mayo. They lived on the so-called correct side of Scotland (known locally as ‘Scottie’) Road – the ‘sophisticated’ side. Before the deluge they had been well established back in Ireland and, by the early years of the twentieth century, had already commenced rising up the social ladder in Liverpool. During the First World War, they were making a reasonable living out of housing working horses (aka stable housing) and also became involved in a little light haulage or ‘carting’, as it was known locally. By the early 1930s my mother’s brother Andy Mottram had expanded his small freight business to incorporate well-known Liverpool hauliers Cameron’s. The Mottrams subsequently dropped their own moniker and traded on this well-established name for many years. Cameron’s wagons could be seen regularly carrying flour along the dock road for the mills of Wilson King, south of the Albert Dock. Money was far from plentiful, however, for it was a very competitive trade and, particularly after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the family only really spluttered along, just like everybody else.

Mother was thus imbued with a sense of business acumen which featured prominently in both my own childhood and adulthood due to the fact that she was forced to finance the family largely from her own funds. This was due to my somewhat wayward father’s tendencies to spend his (albeit hard-earned) money on wine, women and song (as Eric Hobsbawm suggests). So my own interpretation of my family history is rather pro-Mottram, for I feel that I have inherited very little from the Flannery side of my genes. I have always reflected the Mottram sensibilities and these appear to me to be my real family foundations. My sense of Irishness was affected perhaps negatively by the tribal nature of the aforesaid factional echelon system. While I fully acknowledge that my blood is Irish, I have never really considered it to be part of my make-up, as such. One of the great historical myths of our time is that all Liverpudlians, including the Beatles, have been positively affected by their Irish ancestry; I have always disputed this. Liverpool has absorbed many different cultures throughout history, not only that of the Irish (think of the geographical proximity to Wales, for example). Any Irish heritage in the Mottram family featured only sporadically because I suppose that, perhaps apart from the regular intervention of the Catholic Church, it was essentially considered irrelevant. They, like many other immigrant families, were a functional lot. They tended to concentrate on the here and now and there were few if any Mottram longings for an imaginary, pre-digested and idyllic homeland, rearticulated into a Liverpool hierarchy of influence. Liverpool, England, the United Kingdom became their collective home, and for me that was enough to be going along with!

Apart from my mother, my family hero was Uncle Peter, who was a Royal Air Force pilot prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. I still have great memories of Peter in his RAF blue serge, looking so smart. Being smart was an iconic statement for my young self. I enjoyed dressing well even as a child and the attention to detail on Peter’s uniform fascinated me. Peter lived up to his uniform, too, at least in my eyes. He was very suave, sophisticated, with a typical RAF glint in his eye. He served throughout the war, contracting malaria in Burma and finally ending up at the Sealand Royal Air Force camp, near Chester, conveniently close enough at hand for us all (Chester was only an hour’s bus or train ride from our Liverpool home). As suggested previously, however, Chris my father was regarded by the Mottrams as a little ‘low class’, a ladies’ man and a bit ‘fly’. He was treated with a great deal of suspicion by mother’s family and received a hard time from them. I suppose they were, in their own way, snobs, and father reacted very badly to snobbery aimed directly at him for he was a ‘maverick’, recognised himself as such, and was determined that he was seen by others as an entrepreneur. He established a joinery workshop and although teetering on the brink of failure from time to time, he was able to connect with Jewish businesses across the city, seeing himself in the process at the centre of a rags-to-riches saga – thus expanding his locus of business, social and womanising activities. But there was always something of a rift from the moment that he and my mother were married, and it never went away.

So, resentment burned very deeply in my father, I think, and this coupled with the fact that he was always a ladies’ man, somebody who really did desire women, meant that personal calamity and heartbreak never seemed very far from our door. My late mother described him as very handsome when they met. He apparently had a keen eye for detail and when they were courting, his cap, silk scarf and white tennis shoes were the height of fashion on Scotland Road! Six siblings were born between 1926 and 1939, the eldest being my sister Jean and the youngest my brother Peter (later ‘Lee Curtis’). Even when Jean was born in September 1926 and, despite the fact that father doted on his daughter, mother felt ill at ease. It was as if father had a restlessness that simply could not be satiated by a loving family relationship. The all-round disapproval of the Mottrams obviously added to his paranoia for, according to my mother, they were never reluctant to remind both of them that Agnes (mother) had effectively married beneath her.

Father was, and was also known to be, very quick and useful with his fists. It was a man’s world, no doubt about it, and in his eyes a real man had to watch his back. But he took to using his power whenever it pleased him and his violence began to rule our lives. I was born in 1931 and as I grew I became increasingly aware of two distinct atmospheres: one created by my mother’s unconditional love, and another that sprung from my father’s violent presence. A child of 3 or 4 may not know a great deal in the conventional sense of the word but he or she feels a lot. Just like my old friend John Lennon, I’ve always been a great believer in karma. I probably instinctively detected negative karma from my father from a very early age. Funnily enough, the first kind of memory (more of an image or a scene from a play than a memory, as such) that I have is a strange one. I distinctly remember my mother falling down the stairs with my father shouting, at the top, on the landing. I latterly discussed this with mother on more than one occasion and she stated, categorically, that the only time this happened in my presence, so to speak, was when she was carrying me. And yet I remember it as if it were yesterday. Father often moved very fast and silently when his violence came to the fore. No one else would be present (at least that’s what he thought) and he would leave little trace of damage, at least physically. Those areas that were bruised and swollen were usually covered by lint, clothing and dignity.

It became increasingly apparent to my less-than-devoted father after I had reached the age of about 7 or 8 that I was never going to, metaphorically speaking, ‘play football’ – with all of the implications that this must have carried for him. He would almost threaten me, telling me that if I didn’t start kicking a ball around then people would start to question him as a father. He frightened me. I didn’t understand what he was going on about. I mean, I didn’t dislike football, and would occasionally join in with a few other lads in the street, but football as a symbol came to mean so much more to him than me as the years went by. One of the few areas that a man could relate to a boy was through masculinity and he deeply resented the fact that the machismo that was part of physical contact sport was never part of my make-up. Not only had my father apparently married into a bunch of people who (he alleged) looked down on him from a higher social status, but he had also been provided with a son who was a ‘wet Nellie’. I became immersed in psychological tug of war between my parents’ desires for their son. I suppose that it resulted, in the long run, in my mother’s everlasting love and my father’s everlasting shame. It destroyed him that I was not of his mentality. He was ashamed that I could never use my fists. He was chagrined that I was a Mottram and not (by any stretch of his imagination) a Flannery. Yet I was proud of his name, and wanted him to be proud of me – but how?

As I look back upon these rather faded memories of childhood in the Liverpool of the 1930s, I can honestly say that, despite the fear that my father provoked, it was generally more than compensated by the love of my mother and her family. And, even though I cannot truthfully say that I have ever really loved my father, as such, as a consequence of the suffering that he inflicted upon my mother and myself, I feel I can at least try to understand his fatal flaw. The nexus of his crisis, I think, revolved around the status of family life, for he was forever confused about what he regarded as its shackles. I believe he viewed the family as something of a fallacy. Of course the fact that it remains at the centre of Western society’s social universe, irrespective of whether it always works or not, is something of a delusion. I have known young people for whom the family has only meant misery. It is an institution that is regarded as somehow natural, but this has never fully explained itself to me. How can it be natural for somebody such as my father to be evidently so miserable after being compelled to involve himself in it? And don’t tell me that he had a choice, for there was no choice at all. In the 1920s and 1930s, one didn’t choose anything very much. You grew up and you got married.

My father was probably never the sort who was going to lead a conventional family existence; he was somebody who would always walk that very fine line between the safe and not so safe. Being practically driven into family life via peer pressure and convention is not a promising start to adulthood and he found it deeply disquieting, despite loving my mother. I was the living incarnation of a sort of laceration, for Gerard my brother had been born differently, and my father’s hopes lay in my birth. But I proved to be my mother’s son, and he found this to be seriously troublesome – in fact, my constant adherence to my mother’s side proved to be part of a critical period in which important changes to his world view were made, and none were to the benefit of his family, that’s for sure. For example, he was in no way, shape or form a religious man. Yet as a child I wanted to be a priest (I still do, on occasions!); he was a man’s man but he thought of me as a so-called mummy’s boy. He wanted to buy me a pair of football boots, whereas I had my heart set on a pair of dancing shoes. It was all too much for a masculine maverick with a heart of stone, methinks. I functioned as an embodied wish fulfilment for a person who evoked masculinity as power, which for me still leaves a nasty aftertaste – what a disappointment I must have been for him.

So, family life had become something of a sham, even before I had started school. It takes very little time for a child to see through the thin veil of artificial happiness. My father could be a brute; I was living in fear of him for most of my waking hours but, as I look back now some seventy years later, I can see that he had been deluded by society. Not everybody can be a family man. Father subsequently carried this delusion around, like a monkey on his back, for the rest of his life. We, as a family, had to suffer too, and how we suffered. In any case, his violence had apparently begun before the arrival of young Joseph, although my presence undoubtedly exasperated him. He had pulled the bed from under my mother on one occasion, only three weeks before she gave birth to my brother Gerard in 1928. Mother had injured her head on this occasion, and Gerard was subsequently born distinctly different from Jean. There was no evidence to connect one event with the other, of course, but it was generally assumed that Gerard’s impediments were the result of the incident with that bed. In re-examination, I would suggest that it was probably more likely that Gerard was born the way he was after an unhappy pregnancy, rather than one, albeit explosive, incident. My father’s frustration was quite palpable even at this early stage; so too my mother’s ambiguous devotion to this man. The best days of her marriage, according to mother, were the ones that she described as ‘those days of three-pennorth of corned beef and a pennorth of pickles’.

She had very fond memories of the times prior to Gerard’s birth. These early years were times of struggle but relative bliss. As the decade turned, father’s joinery business began to expand and become quite profitable, eventually leading to his first set of wheels for ‘business purposes’. In truth, he was increasingly buying freedom with this acquisition, and following this important milestone for him we seldom saw him during the week. Occasionally we might hear him return home late in the night, having dropped off a ‘business friend’ earlier. An argument would usually ensue, followed by my mother sporting a real shiner the following morning. Occasionally, he would return with Harry Epstein. The Epstein family (pronounced ‘Epsteen’ in Liverpool) were Jewish and Harry’s father Isaac Epstein was from Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire), and had arrived in England in the 1890s, at the age of 18. Harry’s mother, Dinah, was the daughter of Joseph and Esther Hyman, who had emigrated from Russia to England with their eldest son, Jacob. The Hymans would have six more children.

Isaac Epstein married Dinah Hyman in Manchester in 1900. In 1901, Isaac and Dinah were living at 80 Walton Road, Liverpool, with Isaac’s sister, Rachael Epstein, above the furniture dealership he had established. Dinah and Isaac’s third son was Harry Epstein. Eventually the family moved to a larger home at 27 Anfield Road, Liverpool (now a Beatles-themed hotel called Epstein House). After Harry and his brother Leslie had joined the family firm, Isaac Epstein founded ‘I. Epstein and Sons’, and enlarged his furniture business by taking over adjoining shops at 62–72 Walton Road, to sell a range of other goods such as musical instruments and household appliances. They eventually called the expanding business NEMS (North End Music Stores), which offered lenient credit terms, and from which Paul McCartney’s father once bought a piano. Harry Epstein’s wife was formally named Malka (she was always known by her family and friends as Queenie, malka translating as ‘queen’ in Hebrew), and she was a member of the Hyman furniture family, which also owned the successful Sheffield Veneering Company.

So Harry, Leslie and my father were conducting considerable business by the mid to late thirties. My father would manufacture furniture which the Epsteins would retail; from time to time Harry Epstein and Chris Flannery would meet socially. Usually they would arrange a visit to the wrestling at the Liverpool Stadium (promoted by Johnny Best – I would later have a great deal to do with this particular Liverpool family) or the Tower Ballrooms in New Brighton. Harry never informed his wife Queenie of these outings. He knew he was slumming it a little and also realised that Queenie would have undoubtedly considered his activities far too beneath his social status, even a little treacherous and base; as such she was never put in the picture and, right up to her death many years after Harry, Brian and Clive Epstein had died, was never aware of her husband’s class-based felonies. Many years later Queenie actually briefly fell out with me over this.

The birth of son Chris in 1933 followed my seemingly untimely arrival, and the final two pieces of the family jigsaw were conceived in that eerie period of unreal peace that had descended over the country prior to the outbreak of hostilities in September 1939. Peter was a ‘war baby’ for although he was conceived in peacetime he was born at Halloween 1939; Teddy had been born a year earlier. This birth had taken place at my Auntie Winnie’s home at 15 Worsley Crescent in Norris Green. By the late 1930s Norris Green was regarded as a district of Liverpool even though it was actually in those far off days part of the county of Lancashire, on the north-eastern boundary of the city. The estate was developed in the 1920s and named after the Liverpool-based Norris family. It is thought the land on which Norris Green was built on was donated to the city by Lord Derby, but that he didn’t actually own it in the first place – a typical Liverpool story concerning the provenance of land, to be sure! So after much legal wrangling it was actually purchased by the council for the sum of £65,000 from the estate of the Leylands and Naylors; it was then developed into a splendid council house estate – most of its well-built housing still stands to this very day.

Mother had temporarily moved away from the family home in Everton, 16 Walton Lane, along with her brood, because she had not wanted to run the gauntlet of my father’s increasingly violent behaviour. In the latter days of her pregnancy he had again been especially violent to her, and there was no alternative but to try to protect her unborn child, which she did; she then gave birth and promptly returned to him once again, which dumbfounded even us kids. Sounds bloody daft, doesn’t it, but it’s not so unusual. Married life is full of contradictions, I suppose, especially when you are a Catholic family in Liverpool in the 1930s with no visible means of birth control. Under these circumstances what appears to be the most practical and desirable if short-term solution often involves a great degree of personal sacrifice for the woman. Interestingly, however, these first instances of pragmatism on behalf of my mother were productive in the long term, for she began to appreciate that a certain level of independence was vital, and thus her family business acumen began gradually to come to the fore, eventually leading to almost total financial independence from my father.

One might glibly presume that my father’s ideas about the role of his wife were based around that imaginary Victorian principle of a woman’s role being something of an ‘Imperial production line’ of cannon fodder. However, this would be far too simplistic a hypothesis for, as I described, his most violent periods manifested themselves during mother’s pregnancies. As I grew older, this certainly came to suggest to me that his fears of entrapment in the family ‘prison’ were very pronounced indeed. As I write this I feel rather sorry for him in a way, but then again, perhaps not. Whenever I try to understand my father, images return from this confusing period of my life. Such as the day that father almost threw Teddy out of the window because of the child’s incessant crying. Babies cry, don’t they? Why such violence? Why such constant, continuous, catastrophic violence with never the slightest indication of contrition? So, as we all grew through the pre-war thirties, we became increasingly aware of mother’s precarious position. In addition, we were also acutely aware of just how much the Mottrams as a family (and a force for good) were involving themselves in our daily welfare. The Flannery branch were usually nowhere to be seen, except on high days and holidays, and the little practical things as far as we kids were concerned such as sweets and occasional treats were invariably doled out by members of mother’s family.

My cherished auntie, a woman with the wonderful Liverpudlian-cum-German name of Mary-Jane Fitson (a Mottram by birth), was a wonderful human being. Very forceful yet compassionate, she would always ensure that we kids were in safe condition. Her husband Wilhelm Fitson (Uncle Willie), perhaps originally Fitzon, was for us children a ‘mysterious’ German, originally a farmer from outside Hanover who became a teacher in Liverpool. Throughout the growing political tension of the mid to late thirties, we kids would frequently invent exciting stories about him working for the German government or meeting Hitler on the docks or gun-running to Ireland or other such nonsense. A little cruel, perhaps, but that’s kids for you. He was a lovely man, actually, but the total antithesis to Mary-Jane. He was probably Lutheran or some such nonconformist and didn’t attend church too much, whereas Mary-Jane was a totally devoted Catholic. But Mary-Jane was also amazingly nonchalant, dispensing vividly realised observations at every turn. She lived her life in a series of vignettes, each one dispensed as a lesson. Her faith allowed her to combine nuggets of truth with extraordinary moments of mirth and she was always ready to surprise and amuse without over-sentimentalising; she was, I suppose, incredibly wise – a wisdom perhaps brought about by a combination of her faith and her love for a man outside of her social milieu in possibly every sense. This for me has always been the true nature of Catholicism – discipline, yes, but liberation and wisdom also.

Spiritual matters were therefore taken care of by a combination of the Mottram-Fitson alliance together with the illustrious and ubiquitous Roman Catholic Church. St Anthony’s on Scotland Road became something of a refuge for me by the age of about 6 or 7, especially after one of father’s bouts, and I would accompany Mary-Jane to the church in the early hours of most mornings, where she would carry out her duties as a cleaner and I would just stand and stare in wonderment at the pure beauty of the church, as often as not with a rather useless rag in my hand. The iconography used to make me quite literally weep, but in amazement and wonderment that the Lord could have done this for us all. It was all so affective, so emotional and so beautiful. Mary-Jane and I would slowly walk back home, discussing the glory of God, and I would arrive back in time to get ready for school and indulge in a little breakfast: eggs from the Rhode Island Red chickens that were kept in the yard and fresh bread toasted on the big roaring fire to go with them. Butter as well, of course, because of mother’s scrupulous pre-war standards, although it had to be that revolting ‘Special Margarine’ once rationing had arrived. In retrospect, my childhood faith now seems a little cartoon-like; the characters appear and disappear like caricatures, as befits the story perhaps. But at times it was refreshing, invigorating and great fun – at other times less so, for it could fill me with a loneliness that was periodically difficult to shake.

For example, Mary-Jane might, when she could afford it, treat me to a couple of ounces of boiled sweets on the way home, or a few Mojos or Blackjacks from the local newsagent after our early morning pilgrimages to St Anthony’s. She detected, I think, a certain void in my life, a nothingness created by the absence of a loving father. I was later told by Mary-Jane that she worried about me. She had noticed that I tended to stare quite a lot, as if I was looking for something or somebody to bridge a gap. I would stare in church, I would stare out of the window at the night sky and I would stare at the rain falling and running down the gutters at high speed, as if it was escaping from something. Many hours of my pre-teen days were spent looking vacantly around me, hoping that something would come to fill the nihilistic visions that covered an elementary loneliness. She saw. I couldn’t explain it, but Mary-Jane detected it. Many years later I was reminded of such moments by John Lennon’s Strawberry Fields Forever and could envisage a lonely teenaged John, staring into space out of the back bedroom of Mendips in much the same way that I stared at the iconography in St Anthony’s. For me Strawberry Fields Forever has always been indicative of loneliness, with John offering us a private meditational place to share – a wonderfully generous song, I think.

Our walk back from St Anthony’s would always take us past umpteen local newsagents. I would stand and stare outside the shops while many dockers and other early birds would be buying their papers and cigarettes for the day (‘a Daily Sketch and ten Woodbines’ was repeated so often it sounded like a mantra). The iconography in the newsagent’s windows, the advertising posters, papers, brand labels etc., was just as important for me, in its own way, to that of the church; so too the smells: the dampness of working clothes, the wonderful aroma of pipe tobacco – twist, shag, rough cut – all of which probably came from Ogden’s tobacco factory in Liverpool. The physiognomy of the men, all seemingly hundreds of years older than me, gnarled, disfigured, old before their time, but superior, dignified, solemn and proud, very proud: just like the statues and icons in the church. A newsagent’s shop at 6.30 a.m. on a wet Monday morning became an extension of religious experience, an encounter of the inspirational kind; something that has never left me. The orthodoxy of the church mingled with these living, secular experiences and created a template of compassionate reality for the rest of my life. Mary-Jane was distinctly moved about my religious fervour, and she often would discuss with my mother the prospect of my becoming a priest. I thought that this was a wonderful idea, and it fuelled my excitement for all things religious even more. Mother nodded her head in a sort of knowing condescension. She knew in her own secret way even at this early stage that if I was to be true to myself I would not be destined for the cloth.

But I loved the Church so much that I fully intended to immerse myself in the ritual as much as I possibly could; making the sign of the cross before bedtime became part of my life. I totally pestered the priest at Our Lady Immaculate in St Domingo Road, Everton, to allow me to become an altar boy, even though I wasn’t a member of his church. The queue was simply too long at St Anthony’s and I was desperate to do something, anything that would bring me closer to Christ. Poor old Father O’Sullivan held out for quite some time, but was eventually forced to capitulate. He realised, in his goodness, just how much it meant to me. So I was then involved at Our Lady’s and St Anthony’s. I was collecting churches like another lad might collect ice lolly sticks. It was the great mystery of it all too. The Latin Mass was complete gobbledygook, but mysterious and esoteric. The fact that I failed fully to comprehend it only made it all the more special, I think. It took years for me to realise that I was being drawn to the beauty of the Church and its ceremony, rather than the religious message per se. Once a Catholic, always a Catholic, I suppose … yet I do cringe a little these days, now that I have begun to understand the level of indoctrination of the senses that occurred. I would have gone all the way into priesthood, probably, had somebody in the Church decided that I was a suitable apprentice. Into a system, a set of rules, that I would have only discovered at a much later date I was technically disqualified from by an essential guilt; something which, according to some, precluded me from Christianity altogether. Mother could sense the fallacy; she always knew best.

As previously stated, my actual father was a joiner by trade and his initial jobbing employment turned into a full-scale business as the 1930s moved along. In fact, by the late 1930s his work had expanded sufficiently for him to take a small wood yard in Field Street, in the Great Homer Street district of Everton. At first the bulk of the work at the Field Street yard involved manufacturing wooden crates and boxes for canned meats. There were a number of meat producers in the Everton and Bootle areas of Merseyside and crating the tinned hams and ox tongues became a lucrative order for Flannery’s Joiners. In fact, I later discovered that these tongue-and-groove boxes were far more revered than the tinned meat that they contained. The boxes seldom ever ended up as kindling, but came to be used all over Liverpool as ad hoc storage containers. Even twenty years later, as I came to move into my apartment at Gardner Road, I discovered one of my father’s boxes staring at me from the cellar. There it was, easily recognisable to me by the stencilled logo on all four sides of the box reading ‘Pearson’s Butchers’ as if time had stood still. I hadn’t seen the old fella for a number of years by this time and it stopped me in my tracks. ‘I can’t bloody well go anywhere without that sod looking over me!’ I thought as I slowly and nervously opened the box, half expecting something (or somebody) horribly familiar to be looking back at me. My fears were allayed when I discovered an old, battered, but well-used Tilley lamp inside, which I later renovated and subsequently used to good effect. I even raised a laugh as I read a daft little message on a crumpled piece of paper next to the lamp, a relic from another occupant, another life, perhaps another world even, which curiously read: ‘No paraffin, but thanks for the umbrella.’

The shroud of my father was immediately lifted as I tittered with a palpable sense of relief. What the hell was that message all about? I didn’t really care, but I knew in that moment that a spell had been broken. My father’s constrictions had been released by an esoteric message about a Tilley lamp and a rainy day. Maybe the sort of day that in my youth would have had me staring out from my bedroom window, thinking that it was raining because my life was missing something, when all it was doing was just raining. Maybe the sort of night, those cold nights of my childhood, that would make me believe that I was being punished by God for being my father’s son, and then being punished by father for being mother’s son; maybe we were just in need of a Tilley lamp. I suddenly felt better than I had for years, thanks to a tongue-and-groove box from Field Street and an old paraffin heater – but back to the thirties.

As his orders for the Epsteins (and others) became more frequent, father moved to a larger premises on Kempston Street behind London Road, which at that time bordered the Jewish sector of Liverpool. The Epsteins had discovered my father’s talents as a joiner via the aforementioned wooden crates and also a few well-made cutlery boxes (or at least they looked like cutlery boxes: they were actually strong boxes in disguise), and approached him about the possibilities of providing them with good quality but reasonably priced furniture to retail in their shop in Walton Road. Father, despite his faults, was an extraordinary, self-taught man where wood was concerned, and although he had never bothered a great deal with furniture before, he spent many a long night drawing and designing a range of furniture that would prove economically viable and of sufficient quality to satisfy his new client. He had a fondness for unifying features on wooden items; unlike other small-time manufacturers he did not evade particulars and although his private life tended to depend upon inflated rhetoric designed to frighten rather than reassure his family, his approaches to functional woodwork were very particular. The drawings were duly accepted, and thus began our long-term relationship with the Epstein family, an alliance that lasts to this very day. It was initially a good deal for both parties, father providing them with a small quota of chairs and furniture each week, the Epsteins paying every twenty-eight days.

The Epsteins began with good intentions but they proved to be rather poor payers, and it was often left to my mother to go around to the shop in Walton Road, almost cap in hand for money, when the payment didn’t arrive. Despite running the business from hand to mouth, father considered debt collecting to be rather beneath his acquired self-employed status, whereas mother, from a business background, would have no truck with outstanding balances. It was in this way that she came to meet and get to know, at least as far as it was possible, Queenie Epstein who at this stage was the bookkeeper for the furniture shop. Words were usually spoken by my mother about the debt, to which Queenie would remind her of the common business practices of hanging on to money for as long as possible. My mother usually had the last word, however; something along the lines of:

When I’ve got enough of my own to hang onto Mrs Epstein, I will do so as long as I can, with pleasure, but I’ve never been one to keep other people’s money about my person. So, in the meantime, I’d be obliged if you could help me feed my children by paying what you owe my husband.

Queenie – she was always ‘Mrs Epstein’ to us all, in actual fact – came to understand that she was dealing with a formidable adversary in my mother; however, the payments didn’t get any more punctual, and mother’s regular visits, which she found agonisingly embarrassing, came to be something of a ritual. I think it was all regarded by Queenie as something of a game and possibly one highlight of an otherwise rather boring middle-class domestic existence. The business, and this little ritual, continued unabated between the Flannerys and the Epsteins right up until and slightly beyond the outbreak of the war.

At the very beginning, father turned wood from not only the yard at home but also the front room, which had originally been a shop front. Following his business’ expansion and his initial removal to Field Street a portion of our home, his former workshop and storage spaces were left empty. We were living in Walton Lane at this time, very close to the Epsteins’ shop. Once father had moved the centre of his manufacturing away from the Walton Lane area, mother immediately decided to flex her muscles about independence a little and, following in the family tradition, decided to open a second-hand furniture shop in father’s old workspace. This would be 1938. Father actually approached her about her selling some of his goods; however, rather defiantly (and not without a certain sense of business acumen), she refused, claiming that she did not want to give the Epsteins any further excuses for delaying payments to him, or indeed cancelling orders. Of course she also wished to express business as well as personal independence from him. In some respects she saw him as a fraud or at the very least something of a ‘curate’s egg’ – good in parts, but unacceptable as a whole.

It was in this immediate pre-Second World War period that I first met the young Brian Epstein. I must have been about 8 years of age when we first met and, as long as I live, I’ll never forget that first meeting. Brian was a typically spoilt child and initially I must admit to finding him rather repulsive; but, to be fair, this was principally because our young relationship had got off on the wrong foot. It was sometime in 1937, I think, when Brian was placed in my charge one afternoon at the Epsteins’ Anfield/Stanley Park house while Queenie and my mother were doing business. Brian was almost exactly three years younger than myself (born 19 September 1934) and was only a pre-school squirt to me, being all of about 3 or 4 years old and looking very Jewish. He was quite a handful and I thought at the time something of a spoilt brat. So much so in fact that he had me in tears by the end of the afternoon. I had attempted to play with his brand-new toy: a coronation coach (presumably in celebration of King George VI’s coronation that year), which was like a piece of crown jewellery to me. Before even getting a whiff of a chance, Brian deliberately trod on the lead horses, breaking their legs, rather than having it distract my attention away from him. I was horrified, but also petrified because I naturally assumed that, being the eldest, I would get the blame for this act of wanton destruction. I need not have worried, however, because when Queenie returned nothing was said at all. Brian obviously always got what he wanted and the ruined coach wasn’t even mentioned. Queenie gave me the evil eye all right, but more because she thought I was a rather contemptible gentile rather than evil per se. Her one remark to me was cutting enough, however: ‘grubby child,’ she protested.

As time went by I did come to endure him a little and as he grew we became quite good playmates over the next twelve months or so, despite our age difference. Curiously, as I look back now, I think I felt rather sorry for him. He appeared to have everything, certainly more than myself, but was always rather unhappy and at times morose. He later informed me that he was ‘only ever what his mother made him’ – which speaks volumes really. His social and ethnic echelon defined him before he could define himself – a classic case of cultural capital. For example, before I got a chance to get to know him any better the Epstein family moved to Prestatyn in North Wales for a while once the war began. We lost touch for quite a few years after that as, first in Southport and then at a school named Croxton Prep, Brian began his long and painful journey of definition by others, followed by a self-discovery via a command of detail. This was an odyssey which would lead him back into my company more than once over the next thirty years or so.

Meanwhile, mother’s shop had started trading briskly in quality second-hand furniture, plus a little good quality bedding and linen. Mother’s new-found assertiveness was in no small way linked to her family background of entrepreneurial know-how. As she began to visit local house clearances and auction rooms she immediately recognised a need in the local market and, having a good eye, spotted some very tasty furniture. She also appreciated our house/shop’s position, which was in an area of very low wages and high unemployment, and as such was in the middle of a district which has always been reliant on second hand as something of a financial necessity. Wardrobes, beds, washstands, cupboards were the staple sellers, along with the ubiquitous dining table. Mother was particularly adept at discovering house clearances in the more middle-class, salubrious parts of town, and would often jump a tram to Woolton in order to place her marker or get first refusal on furniture from some of the larger houses out there. Mention of Woolton demands a brief explanation, for it was around this very area that the young Quarry Men and Beatles could often be found, and their experiences of that area of Liverpool form a contrast between their upbringings, and that of my own.

Woolton is another of those districts of Liverpool that was initially co-opted into the corporation. Of course many Beatles landmarks can be found in Woolton, including Mendips (John Lennon’s childhood home at 251 Menlove Avenue) and what we knew as the naughty boys’ home of Strawberry Field, off Beaconsfield Road. Another one of Woolton’s claims to fame is that John and Paul first met at St Peter’s church garden fete on 6 July 1957. It would be worth reminding all Beatles fans of this fact the next time they considered them working-class heroes – in fact, wasn’t this irreconcilable difference actually what John was singing about all those years ago (i.e. that effectively ‘you made me into your working-class hero’)? Not every young boy had the opportunity to read volume after volume of Just William, that’s for sure (I think of myself as one such example).

But enough of the rant and back to the story: quality and value became Agnes’ trademarks for families who had little or no spare cash to spend on even the barest of necessities. While mother was providing herself with regular, if unremarkable, income, father and the Epsteins (and the Jewish community in general) were getting on like the proverbial house on fire. Not only from a business point of view, either, for it was about this time that my father and Harry Epstein took to socialising and drinking together – as mentioned earlier – much to Queenie’s ignorance and my mother’s fear. The Epstein outlet was proving to be rather lucrative for Chris Flannery, despite the late payments, and by the end of 1938 he was even providing their shop with some rather classy Queen Ann reproductions. Most of this stuff was destined for the more salubrious areas of Liverpool’s suburbs: Queens Drive, Woolton Road, Menlove Avenue in the south end of the city and also Formby, Waterloo and Blundellsands in the north, in addition to the Wirral, over the water.

However, father’s new-found wealth simply increased his desire for booze and freedom. Mother would frequently tell us, when asked about where he was: ‘Oh, I don’t know … once your father got four wheels and then a little money in his pocket, he was a changed man.’ I was pretty glad to see the back of him most of the time for once he had walked back through the front door our own version of a world war would usually begin. A good wash in front of the fire in the galvanised bath, snuggling up to mother to listen to the wireless and smelling that familiar scent of ‘Evening in Paris’ that she would always wear made us feel safe, at least for a while. If there was nothing worth listening to on the wireless she would sing all of her favourite songs such as Me and My Shadow,You Made Me Love You and One of These Days.

Music actually became a real comfort; it was at the very least a soundtrack to a degree of temporary peace and stability. Father, of course, couldn’t have cared less about music. He was the antithesis to all things musical: he regarded a musician as somebody to be suffered, somebody who could provide a service while he was chatting up his latest bit of ‘fluff’. But to mother and myself it was an ‘other’ world. Radio itself was full of fascination, excitement, entertainment and it became a refuge; a place that we could visit when times became unbearable and father’s behaviour became insufferable. It wasn’t simply the songs of Sophie Tucker either, but practically any music or show. The wireless became a medium of transportation to other lifestyles, other existences. Excitement leapt from the airwaves to soothe us; there was another world out there! Not every man was a beast, it seemed – some like Henry Hall, Ambrose, Lew Stone, Roy Fox and Ray Noble actually loved music as I did. My memories of mother washing in the yard, turning that huge wheel on the side of the ringer until it reached top dead centre are forever meshed with memories of sounds reaching out to me from the wireless, with mother singing along to something like Whispering.

Looking back to the 1930s after so many years, it seems at times that we were constantly surrounded by music and the smell of carbolic soap. As if, in some strange way, Stan Kenton had something to do with the big tin bath hanging on the backyard wall. But, of course, the memories of my wayward father also at times return to haunt me, returning one’s thoughts to reality, and fear. Actually, visions of my father during the war can occasionally make me smile. To his utter astonishment, and my hilarity, he was called up. I thought that this was not only an excellent thing for the War Office to do for the country (in my childish way, I thought that because he was so violent he could sort it all out), but also for mother and myself, because he would be away from home. Initially, he was posted as a Royal Engineer to Devizes and life was heaven without him. He was still alive and I never wished him dead, at this stage, despite his violence, but he was simply not around and almost immediately the atmosphere in the house changed: mother was safe; the Mottrams were free to call; music could be played all day; and we could all live in a little peace. How completely ironic that this threat to the nation could have given the Flannerys so much joy! It was not to last, however, for father was posted back to Liverpool, after his training in Wiltshire to work as a joiner-cum-docker on the Liverpool waterfront. He even came home for his dinner – as often as not with a shoulder bag full of something that had been mysteriously damaged in transit that morning; sugar immediately springs to mind (perhaps he was not all bad, but then again, I wonder which family was being deprived of this precious commodity via his pilfering).

Oddly, and unlike other fading images, such memories are vivid, maybe because other boys’ fathers were thousands of miles away fighting for King and Country, and yet my own could jump a tram and be home in half an hour (and according to my mother create World War III back in his own kitchen). I was excruciatingly embarrassed. In addition, he frequently returned home carrying his Lee-Enfield rifle. Other boys would have found this fascinating, but to me it was only emphasising my feelings of foreboding about him and our relationship grew even more strained because of my inability to come to terms with his bringing this symbol of violence into our home. The business was still thriving too. Despite his war work, father was now also able to keep an eye on his profits, and owing to the Blitz of 1940–41 he discovered that he was in great demand. The wood yard was able to provide a boarding-up service for first of all Irwin’s retail grocery chain, which was much later taken over by Tesco, and later for many of the devastated homes, and father was paid handsomely for the service. He also took a great interest in reclaiming salvaged wood and reworking it, and this became a very lucrative outlet as the war continued and fresh wood became scarce. On the whole it was a pretty good war for the man.