Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Blitz survivor, ex-evacuee, veteran of five primary schools and product of a typical London suburb, Berwick Coates won a scholarship to a grammar school in 1944. All he knew about was German aircraft recognition, cricket and Hollywood films. During the following years, he had to deal with new surroundings, new subjects, new friends, V-2 rockets, his parents' broken marriage, adolescence and a post-war culture of shortage. Fortunately, he was taught by some memorable teachers, some of whom helped to shape his later life and teaching career. His account of life at a grammar school in the 1940s is interwoven with the historical context of this turbulent decade, which saw not only the devastation and deprivation of the Second World War, but also the hardships faced by a country rebuilding itself afterwards. The author's experiences will resonate with anyone who has followed a similar path.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STARKEYE & CO.

Kipling wrote a school story called Stalky and Co. One of our earliest headmasters was a ‘Maystere John Starkeye’. And one of our senior teachers had the nickname ‘Sarky’. Hence the title.

The school mottoBene agere ac laetari – ‘Work well and be happy about it’.

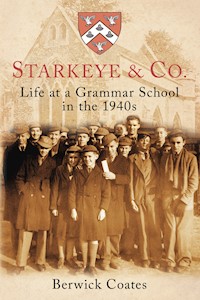

The class of ‘44, taken in ’49, the year we took School Certificate (incidentally the very last School Certificate, superseded by ‘O’ Level, and, in 1988, by GCSE).

Back row, left to right: Mike Woodman, Mike Harrison, Ken Bourne, Malcolm Betts, Bruce Gould, Peter James, Derrick Cowling, Peter Hunt, Brian Welch, Michael Keedwell, Alan Dixon. Middle row, left to right: Ian Campbell, David Clark, Peter Money, John Beaumont, Neville Lewcock, Peter Colato, Tony Barrell, David Meech, Stuart Owen, Peter Barrett. Front row, left to right: Peter Gent, Keith Rogers, Ron Lindsay, Roger McDaniel, Mr Brown, the author, Michael Pratt, Colin Gamage, Phillip Chapman, Donald Wilson.

STARKEYE & CO.

Life at a Grammar Schoolin the 1940s

Berwick Coates

First published 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Berwick Coates, 2011, 2013

The right of Berwick Coates to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9686 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction

1

What Does E.N.S.A. Stand For?

2

A Suitable Case for Treatment

3

The League of Pity

4

Mardi le Douze Septembre

5

All Stations to Waterloo

6

One Side of the Truth

7

A Peak in Darien

8

Cercle Français

9

Into the Palm Court

10

In Corpore Sano

11

Lords of Lord’s

12

Spare the Rod

13

Broadway Melody: I

14

The Play’s the Thing

15

Kulturkampf

16

Supporting Cast

17

Broadway Melody: II

18

La Belle France

19

The Banging Spoon

20

Class of ’44

21

Being Prepared

22

Knickerbocker Glory

23

The Cool Sequester’d Vale of Life

Introduction

Starkeye and Co. is an account of, and a tribute to, some of the remarkable men who were my teachers. It is also an attempt to give the flavour of what it was like to go to school, live in a suburb, and generally grow up, during and immediately after the war.

Such a narrative is not likely to be in any way special; indeed, such value as it may have will come, I should guess, from its familiarity rather than from its uniqueness. Therefore, if there is such a word, I hope the book may possess the quality of ‘identifiability’.

Certainly it is not a work of history. So I can anticipate those old members of the school who may write to me and point out errors by saying now that they are quite probably right. I have not sought scholarly accuracy; I have not scoured old magazines or quizzed old school friends or compared evidence – all of which has made the book easier to write. Besides, too much accuracy tends to spoil the best stories. Stories, like good wine, improve with age, and why shouldn’t they?

My purpose is solely to entertain, and my instrument has been memory alone. Memory may be faulty, but, I hope, not malicious. If I should cause pain or embarrassment to any ex-member of the staff or any ex-pupil of my school who may read this, or be told about it, may I apologise humbly and sincerely, and assure him that such was not my intention.

1

What Does E.N.S.A. Stand For?

I thought Jimmy’s signature was terrific. It didn’t bother me one bit that I couldn’t read it. Even at 10 I understood that headmasters were busy people, and it was nothing remarkable that they should have illegible signatures. After all, what with routine correspondence, school notices and hundreds of reports to sign every term, it is small wonder Jimmy was tempted to let the thing degenerate into a formal squiggle. At least it was familiar to all those under his authority – which was what mattered.

When I first saw it, on a letter to my mother requesting me to attend for interview, it was its very illegibility that impressed me – its nonchalance, its cavalier dash. All the other teachers’ signatures I had seen had been those of primary level; they always seemed to sign their names as if they were still putting handwriting exercises on the blackboard for their classes to copy. Clearly, a man who could fling such a flourish on to the bottom of a typed letter must be someone of immense learning, sophistication and – well, charisma. The fact that his name was actually James was merely by the way. It was a long time before I discovered that the initials were E.W.H.

Jimmy’s signature.

It was even longer before I found out that they stood for Edward W. Harold. (To this day I do not know what the W. stood for.) This information I gleaned from a pair of large boards nailed high to the wall at the back of the stage in the hall. On them were engraved the names of every headmaster in the school’s history. Since high on the list was a ‘Mayster John Starkeye (c. 1272)’, one could not help feeling that a certain licence had been taken in the interpretation of extremely sparse documentary evidence in order to provide the school with such a lengthy lineage. A cynic might be tempted to compare it with the suspiciously comprehensive list of early popes on proud display in that big church in Rome.

However, the annalists were on safer ground with the twentieth century, and if the board stated that Edward W. Harold James became headmaster in 1940, it was reasonable to accept that he did. Of course, to small boys just about to enter a venerable grammar school for the first time, headmasters were not appointed; they did not have a past; they just were. One only pieced together their background through years of grapevine gossip. As boys’ sources of information were other equally ill-informed boys, most of whom were anxious to tell a good story, the picture that one gradually built up could hardly be said to be balanced.

We heard, for instance, that Jimmy owed his appointment to the fact that the previous headmaster, one Charles Howse, had fallen down the stairs. He really did fall, by the way; Jimmy didn’t push him. The negligent Mr Howse’s accident had not been fatal, but the effects of the fall were lengthy and painful – it was a stone staircase – and apparently very damaging to his nervous system, already in a fragile state owing to the German bombing. A slightly premature retirement followed, and Jimmy James, the deputy headmaster, was invited by a distraught board of governors to step into the breach and carry on for the duration.

So far the picture, if sad, was a consistent one: elderly gentleman, the pressure of work, the toll of the years, the added strain of wartime austerity and physical danger, the sudden painful injury, the quitting of the stage. What we found difficult to reconcile with all this was the alternative cycle of Howse legends relating to his actual tenure of office.

For instance, he was acknowledged by all memorialists to have been a terrifying disciplinarian. Small boys had been known to wet their pants if he stared at them too long. Whether the stare was fixed or absent did not matter; the predatory-serpent element in the eyes was enough to produce involuntary evacuation of many a pre-pubertal bladder. Members of staff coming down the stairs from the common room on their way to take lessons often encountered him standing outside his study with a turnip watch held significantly in his hand. His deputy, Jimmy James himself, was reputed to leave the games field and walk up the road whenever he wished to enjoy a pipe during a school cricket match on a Saturday afternoon.

Then too, the late Mr Howse had been a law unto himself in all matters concerning school routine. Morning assembly was a case in point. His many years of conducting prayers produced such clockwork mastery of the timings and spacings of the simple ritual that it became his practice to sit at a table on the stage and read his morning’s correspondence during the proceedings. When the prefect had finished reading the passage of scripture appointed for the day, the loud silence flicked a small switch in his preoccupied mind. Without looking up from the latest government circular he would say ‘Our Father’, and the entire school would obligingly recite the rest of the Lord’s Prayer. A second silence flicked a second switch, which sent him into a mumbled rendering of a last blessing, and the school filed out in a further silence broken only by the swishing of the paper-knife.

Occasionally he got his wires crossed, and at the second interval would say ‘Our Father’ for the second time. After a moment’s incredulous unease, the school would respond with Pavlovian fidelity, and recite the Lord’s Prayer all over again.

However, the awe-inspiring Mr Howse, with his fearsome authority and his fine disregard for Holy Scripture and ceremonial, was no mere freethinking bully. He was a man of infinite guile and subtlety too. In his relations with his staff he was, like Charles II with his politicians, always one jump ahead. The most oft-quoted example of this, usually delivered in tones of furtive, self-righteous shock, was his treatment of staff who wished to escape his wintry rule. Bad teachers were always provided with glowing testimonials, which dazzled any interviewers into immediate offers of new posts. Good staff he was unwilling to lose, and their testimonials mysteriously failed to please the governing bodies of other schools. Of course, he would not tell lies, or actually run the man down; but there were ways – the hints, the euphemisms, the circumlocutions, the glaring omissions. It was a sinister art, at which the devious Mr Howse was a past master.

Here then was the paradox. The first crop of Howse stories sketched in a picture of a frail, accident-prone Mr Chips broken by the wickedness of war and the slipperiness of a malignant staircase. The second cycle of legends, with their alternative emphasis on his cunning, his arbitrariness and his capacity for striking terror, produced an alarming portrait of Machiavelli, Sir Roger de Coverley and Attila the Hun all rolled into one.

It would seem to say something for the school’s resilience that it weathered no fewer than twenty-seven years of this stark autocracy. That took the school’s history back to 1913 and to the only other name I remember on that imposing roll of honour above the stage. The incumbent during the late Victorian and Edwardian era had been a shadowy figure called the Rev. Inchbald, of whom no stories survived. During the many longueurs in music lessons (always held in the hall in front of the stage because there was no classroom available to take a piano), I would frequently gaze up at his name – Rev. Inchbald – and build for myself a picture of a shiny-pated, penny-pinching clergyman, lording it over a cowed congregation of pale-faced youths all dressed like illustrations from Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

The assumption about dress was a natural one for a small boy whose reading fare at the time included racy accounts of the goings-on at a fictitious academic institution known as Greyfriars. The reality, in the days of the doodlebug and clothes rationing, was very different, and although the school regulations officially prescribed a grey suit as desirable, it was admitted that a certain latitude had to be allowed owing to the scarcity of clothing coupons. (For the benefit of those who do not appreciate the reference, I must explain that clothes too were on ration, and had been for two or three years.) As I presented myself for interview in a blue suit, and second-hand at that (though my mother always maintained, in our many discussions about this years later, that the suit was brand new), I was acutely conscious that my mother and I had interpreted the phrase ‘certain latitude’ with considerable freedom. I would not have been surprised if I had been ordered to leave on the spot, without even getting in to see the headmaster.

I was already nervous as a result of the visual impact created by the outside of the school. On the edge of a wide pavement, about 20ft from the road, was a low brick and concrete wall, in which had once been fixed, presumably, some iron railings. Behind this stood some large, straight-trunked trees, rather like sentinels. The earth around and between them was always bare, dry and hard, with the result that you somehow never thought of the trees as alive. It did not occur to you to look up to see if there were any leaves. They were the sort of trees you imagine a film director would use for the main drive of Wuthering Heights or Baskerville Hall.

Behind them lurked a double-storey facade of red brick, which a well-wisher would call mellowed, and which an evilly disposed critic would refer to as worn and grubby. To the left, as you looked at it, was a huge corrugated iron shed for bicycles, and to the right a passageway led towards the quadrangle past a tumbledown terrace of outhouses used for storing broken desks, bits and pieces of old stage equipment and general junk which successive caretakers had considered might come in useful some day.

The huge sash windows each had a lower half in frosted glass and were devoid of any curtaining. The front doors boasted a bleak pane of glass apiece and were shaped to form a pseudo-Gothic arch. The brass plate affixed to the wall on the left had had so much of its surface worn away that you could only read the lettering if you stood and craned your neck at the right angle in relation to the rays of the sun. From the road, one had no indication whatsoever of the purpose of the building – there was no notice board. It could have been anything from a union workhouse to the town residence of an impoverished duke.

Frankly, I would much rather the school had been housed in the medieval-looking chapel on the other side of the road. It looked the part so much more. (It was quite a long time before I discovered that it originally had been.)

But no, I was stuck with the red brick.

The front doors were heavy and shut behind you with a noise reminiscent of dungeons. As you crossed the threshold, you knew what Edmond Dantès had felt like on arrival inside the Château d’If.

One thing did reassure me, though. I was told to wait in the passageway outside the headmaster’s study. It was the word ‘study’. It conveyed warmth, authority, learning, remoteness, peace, pipe-smoke and tradition, all in five letters. Perhaps too it provided a feeling of ease and familiarity because of the apparent connection with the delights, nonetheless envied for being fictitious, of Greyfriars, where nearly everyone seemed to have a study, from Mr Quelch to Coker of the Fifth and Loder of the Sixth. It was the one cheering ray of light in an otherwise gloomy experience, for the interview, when it came, was, so far as I could judge, a disaster.

Jimmy sat at a desk of dictatorial dimensions, without appearing diminished by it. He had a moustache and a good head of frizzled hair, set close to the scalp, of a colour that fashionable novelists once used to describe as ‘iron-grey’. The face was impassive, yet managed to convey alertness. The eyes examined you over those little half-glasses that enabled an interviewer to glance down at a paper and look up at a candidate without any perceptible movement of the head. The very stillness made you feel somehow at ease and on your toes both at the same time. The overall impression was of a man to whom one told the truth.

The Lovekyn Chapel. The womb of firstly Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School, founded in 1561, and later of plain Kingston Grammar School. Its foundation went back to the thirteenth century. It claims to be the only surviving free-standing chantry chapel in the country. (Courtesy of Kingston Grammar School)

The interior of the chapel. Over the years it has served as prep school, carpentry workshop, rehearsal room, studio, and, as shown here, gymnasium. How many schoolboys can claim to have done their forward rolls in front of gothic windows? (Courtesy of Kingston Grammar School)

Once the questions began, however, the feeling of ease quickly evaporated. Certain faculties perversely deserted me at the very time I needed them most. Discretion, intelligence, memory, gumption – all left me high and dry in the face of what seemed perfectly straightforward enquiries. A capricious Providence left me only with the gift of articulate speech, so that I was able to reply ‘I don’t know, sir’, and could not even plead the dumbness of stage fright.

I reached the nadir when Jimmy said, ‘Do you know what L.P.T.B. stands for?’

Well, of course I did. I was one of those boys who collected useless information like stamps. I had notebooks full of lists of initials and abbreviations and highest mountains and longest rivers and Grand National winners and so on. L.P.T.B. was child’s play – in my case literally. At least it should have been. But something went wrong with the machinery; the brain simply would not transmit the message to the tongue. If only he had asked what C.I.D. stood for, or O.M. or MSS. Or the real showpieces like G.C.V.O. or K.O.Y.L.I. A few more seconds’ fruitless mental battle convinced me that the answer was not going to get anywhere near my vocal chords, so I glumly said ‘I don’t know, sir’ for the umpteenth time.

Jimmy made a noise which appeared to indicate that he considered my answer very significant indeed, and looked down through his glasses again. I could feel my prospects fading like morning mist in the summer sun and braced myself for the impending curt dismissal.

After a lengthy silence Jimmy looked up. He had clearly decided to give this ignoramus one last chance. The ignoramus collected his few remaining resources for one final convulsive effort … Ask me another set of initials. I’ll show you. Go on – any one you like … Jimmy cleared his throat impressively.

‘Do you – er – do you know what E.N.S.A. stands for?’

Well, that was that. Nothing else for it but to admit defeat and withdraw in as good order as possible. No point in wasting any more of his time. I straightened my shoulders.

‘No, sir.’

‘No, neither do I.’

I have no recollection of how the interview ended, but I do remember the incredulity being followed by relief and then by a sense almost of intimacy. In those four words, Jimmy had managed to convey his relief too – relief at having found a kindred spirit. Here were two mature minds which thought alike, which could not be bothered with the tiresome trivia of wartime jargon. He had conjured camaraderie out of the air.

All the time I knew Jimmy, I never lost the initial impression he had so magically created that we somehow spoke the same language. That was not to say that one was ever tempted to become familiar. He was one of those rare people who could inspire affection and awe at the same time.

He beat boys, too. He could growl and he could bite. He was a fine exponent of the Napoleonic maxim about keeping subordinates on the hop. Stories were told of his alarming habit of turning on the gas of the Bunsen burner and then groping absently for the matches. The most unruly miscreants would pause in their evildoing to gaze in fascinated horror as he fought his way through fold after fold of tattered gown to pat each waistcoat pocket. A few more seconds of puzzled grunts and the deadly hiss of escaping gas were enough to crack the strongest nerves. By the time he actually located the elusive Vestas, nothing could be seen of the class except a few stray elbows. It was worse than the flying bombs.

Jimmy James. Our headmaster during the very worst period of the whole twentieth century. Scores, maybe hundreds of similar schools must owe a colossal debt to men like him who kept them going.

Jimmy had his prejudices. I used to hear, many years later, that you ‘either got on with him or you didn’t’. Colleagues who were willing to put their foot on the rail and their hand in their pocket in the Three Tuns up the road were among those he apparently ‘got on with’. Ladies who lacked a sense of humour were not. A long-serving school secretary once told me that Jimmy had had ‘trouble’ with her predecessor because she was too solemn and serious. During the overlap period when she, the newcomer, was learning the ropes, Jimmy would conduct most of his business with her if he could, referring furtively to the retiring incumbent as ‘the wench’.

Looking back, though, one cannot begrudge a few prejudices to a very human man who, at a late stage in his career, took on the responsibility of running a school in wartime. No doubt it was a fate which befell many a middle-aged deputy head at the time, up and down the country. No doubt too the problems were common ones: the disruption caused by air raids; the loss of valuable staff, particularly games staff, to the services; the effects of clothes rationing on the standards of school dress; the inadequate facilities to meet the increased demand for school lunches; the shortages of everything. These steady, practical, unobtrusive, unfussy, loyal men kept hundreds of academic ships afloat. They are among the unsung heroes of the profession.

Boys, however, are rarely aware of the general picture. They are to a certain extent insulated by their own ignorance, and take in their stride a series of crises and problems which more knowledgeable adults might wring their hands over. So the stories grew about air raids, and bombs on the playing fields, and public examinations in boiler rooms – oh, and the V-2 rocket which fell nearby, right in the middle of an afternoon French lesson. They were just incidents which broke the monotony and provided fuel for gossip.

None of it seemed to get them down, and none of it seemed to get Jimmy down either. His problems, moreover, were not ended with the coming of peace. Post-war austerity was even more stringent than wartime rationing. Staff were even more difficult to get – at any rate suitable staff. Masters came and went with suspicious rapidity. All this must have presented wearisome problems of discipline, yet one never got the impression that Jimmy lost his grip. And there really were some dreadful boys in the place. One or two frankly terrified me; they had the gleam of the hunter in the eye, as if they ate juniors for breakfast and spent their mornings preparing stake-filled pits to ensnare credulous new staff. You could almost see their fangs. Juniors were not entirely guiltless either. We once reduced a man to tears – and he was one we liked.

Even so, those difficult years must have taken their toll without our knowing it. In 1949 Jimmy announced his retirement, whether due to ill health or advancing age I don’t know. Probably both. I believe too that he had lost a son in the war. When the time came for him to say goodbye to the assembled school, his wife came to tell us that he was too ill to be present, and it was she who shook hands with representatives of the various forms. The passage of years has removed all other details of the occasion, but the moving quality of it remains fresh in the memory.

Jimmy made his mark. The toughest of trouble-makers had not only respect for him, but affection too. And, oddly, fellow feeling. After all, they reasoned, a man couldn’t be all bad who in his biology lessons used to employ yellow chalk to indicate the bladder.

2

A Suitable Case for Treatment

Well, that was the school I was going to, and that was the headmaster who was going to be responsible for my secondary education.

Jimmy had magnanimously overlooked my ignorance about ENSA and the London Passenger Transport Board, and had offered me a scholarship, but what sort of boy was he getting in return? What potential for learning and citizenship did he have to work on? Just what was he letting himself in for?

Certainly nothing normal, because this was the fifth year of the war. Or rather, since it was the fifth year of the war, all sorts of things generally accepted as abnormal had become normal – like the blackout, and nights in air-raid shelters, and explosions everywhere, and shrapnel in morning gutters. One could go on: gas masks, ration books, white helmets on air-raid wardens’ heads (‘Put that ruddy light out!’), the sirens, people in uniform everywhere, sticky paper on window panes, taking your own newspaper to the shop to wrap the fish …

I had been evacuated to three different places. The primary school from which I had taken the scholarship examination was my fifth in three years. However, I did manage two consecutive years in this last one, a red-brick edifice known officially as Merton Bushey Junior Mixed.

To get there from where I lived you walked along from the railway station to the corner of West Barnes Lane, crossed over by the garage, turned left and walked up West Barnes Lane itself. That took me to where my friend Georgie Winters lived. Georgie had started at the school on the same day as I had, so we struck up a friendship. Georgie’s father ran a shop which sold bits and pieces of motor cars, and bits and pieces of practically everything else. Oh – and he had a wooden leg. You saw a lot more men with wooden legs in those days than you do now.

The wooden leg did not seem to have impaired Mr Winters’ extracurricular activities, because Georgie had numerous brothers and sisters, and they all lived in a dusty flat over the shop. The eldest, Roy, was a hard-bitten 14-year-old who had just left school. The school-leaving age had not yet been raised to 15, never mind 16, so Roy was quite entitled to be out. Mind you, if the school-leaving age had been 12 or 19, I don’t think it would have deterred him from being either in or out as the mood took him; he regarded all learning and authority as mankind’s natural enemy in life’s war of survival. I had never seen a boy of his age who appeared so fierce and belligerent; he always looked as if he was gritting his teeth for a fight.

I also remember Joycie, and a very tiny one called Peter, who ran around the flat with a jersey on that was too small for him – and nothing else. Mrs Winters had glasses and smoked.

My mother had her reservations about the salubriousness of Georgie’s surroundings and the sartorial standards of his family. I suppose he was a bit of a scruff, but he was all right, was Georgie.

We collected train numbers together and shared our marbles. I didn’t share his enthusiasm for the cubs, but it was he who introduced me to the story comics that were popular at the time. During my evacuation, I had had to make do with relatively unsophisticated fare like Radio Fun and the Beano. Perhaps that was all they had deep in the countryside of North Devon and mid-Surrey. Thanks to Georgie, I now discovered the Adventure, the Hotspur, the Wizard and the Rover, all of which had long meaty stories, so long that the traditional comic strips got a very meagre look-in.

I made the acquaintance of a rich gallery of literary characters, like Rockfist Rogan, the demon pilot of Fighter Command, whose list of knockout victories in the ring was equalled only by his tally of Heinkels and Messerschmitts in the air. And Solo Solomon, a resourceful cowboy who used his convenient gift for ventriloquism every week to get himself out of tricky situations with dastardly rustlers or bank robbers. Then there were the ebullient pupils of the Red Circle School, who spent all their time having the most exciting adventures instead of sitting in class like the rest of us and listening to dreary teachers. And there was Wilson, Wilson the wonder, Wilson the super athlete, who put the weight impossible distances, and who ran the last hundred yards of the marathon in ten seconds flat to finish in under two hours.

How did he do it? Ah, you may well ask. To find out, you had to read ‘The Truth about Wilson’ every week. Even then the editors cheated and only gave you detailed descriptions of his athletic feats and of the symptoms of strain and fatigue that Wilson underwent. There were mysterious hints here and there that Wilson was not as young as he might be, and he wore some middling queer athletic gear too, judging by the illustrations. But there were no real explanations. We were kept dangling for months and months, and the editors didn’t really come clean until the much-advertised ‘Further Truth about Wilson’. Then we discovered that he was the possessor of a secret elixir of life and that he had been born, in Yorkshire, in 1795 no less. Remarkable chap, Wilson.

I drank it all in, week after week, as Georgie generously passed his comics on to me. I wonder how many 8-year-olds nowadays regularly devour comics containing so many pages of densely packed, solid reading. I don’t know if it ‘proves’ anything about changing educational standards. Perhaps today’s kids would hoot with laughter at our lack of sophisticated taste in reading. Probably we, had we been favoured with the choice of densely written comics or television, would unhesitatingly have chosen television. Times were simply different – voilà tout.

One last debt I owe Georgie concerns Robin Hood. I suppose I had heard of Robin by then, and Little John and the rest. But Georgie had been given a book about Robin and, as I was his ‘best friend’, he showed me. It contained some of the most sumptuous pictures I had ever seen.

I now realise that the book was a story-and-picture version of the 1937 Hollywood feature – you know, ‘the book of the film’. But those photographs – the vivid greens of Robin’s jerkin and tights, the rich brown of Friar Tuck’s habit, the gorgeous purples of the Bishop of the Black Canons’ robes (now there was a furtive villain if ever I saw one, always looking out of the corner of his eye) – so electrified my imagination that when I later saw the film itself, it came as no surprise to find Errol Flynn, Basil Rathbone, Eugene Pallette, Claude Rains, Alan Hale and all the rest in the main parts. It was perfectly obvious and natural. Errol Flynn was Robin Hood; Basil Rathbone was Sir Guy of Gisborne; Montague Love was the shady, devious, oily Bishop of the Black Canons.

So I picked up Georgie Winters and we walked up West Barnes Lane, with a copy of the Adventure in one hand and a catalogue of Southern Railway steam locomotives in the other.

Shortly after leaving Georgie’s house, we passed under the railway bridge and noted number 319 for the fiftieth time. This little shunter toiled regularly up and down a small branch line that ran beside the road. This was before nationalisation, remember. I believe one of the old puffers even sported the initials L.S.W. – London and South-Western. Certainly many carriages carried ‘3’ on their doors. You either travelled ‘First’ or ‘Third’ class. There was no second class. (Now they’ve got rid of all that. We have ‘Standard’ now; no passenger must be made to feel inferior. I suppose they’ll change ‘First’ to ‘Executive’ one day.)

We paused outside Carter’s Tested Seeds, a huge nursery fronted by an incongruously ornate building, where, presumably, the seeds were inserted into those colourful little sixpenny packets that adorned the racks in the local ironmonger’s. It seemed an unnecessarily impressive facade for such a humble industrial process.

There was a large forecourt too, in the centre of which was a fishpond. The pond was flanked by two life-size statues on plinths. One, white, was of a well-endowed young lady whose clothes had mysteriously slipped off her shoulders, but which, even more mysteriously, had been caught by some hidden force round her hips in total defiance of gravity. It never ceased to surprise me how many statues there were in the world of well-endowed young ladies who concealed this anti-gravity device in their clothes round about the level of the hips.

However, if this display of bare flesh, albeit in stone or plaster, was pretty scandalising, you should have seen the other one, the black one.

This represented a young man who, so far as we could see, had no clothes on at all. We were not absolutely sure, mind you, because the young man was leaning forward slightly in some athletic posture or other, and the shadow of his upper body fell across his lower in such a way that it was difficult to discern from the distant pavement whether the sculptor had been totally faithful to realism in his modelling of the full anatomical detail of the lower torso. Or, as Georgie put it in his chirpy way, ‘I wonder if ’e’s got one’.

One day, Georgie found out. We had ventured into the forecourt to gaze at the goldfish in the pond, and raised our eyes furtively in the direction of the black boy’s gleaming stone flesh. Unfortunately, the leg that was thrust forward in his running was the one that was nearer to us, so the question was still unresolved. There we hesitated, unanswered, while the statue preserved its secret, a tantalising 20 yards away.

I was all for giving it best and beating a tactical retreat. After all, we weren’t supposed to even be by the pond; it was private property and we were a good 15 yards from the road. The Puritan hypocrite in me would have been quite happy to know the answer, but did not wish to be observed in the act of making an effort to find out.

George was made of sterner stuff.

‘I’m going to ’ave a look,’ he said.

I hung about uneasily, hoping nobody would come out to ask us what we were up to. To me those 20 yards were as fraught with danger as No-Man’s-Land on the Western Front. Waiting was almost as bad. Anyway, Georgie made the dash, paused, crouched, looked up, and came charging back, grinning and smirking all over his face.

‘It’s there! ’E’s got one!’

We legged it back to the road as if we’d been planting explosives, Georgie triumphant, me wondering guiltily whether the acquisition of such anatomical knowledge was worth all the suspense, embarrassment and agonies of conscience. It was a relief to get to school and get on with something less demanding.

I don’t suppose there was anything particularly special about Merton Bushey Junior Mixed. It was built on traditional lines of school architecture – a two-storey, red-brick, rectangular edifice in the middle of a grey asphalt playground. Part of the ground on the left had been taken up, inevitably, with rows of air-raid shelters, but the school still retained, oddly, its iron railings, which had somehow escaped the attention of the Ministry of Defence when it decreed the removal of all such metallic boundaries and decorations – and kitchen utensils – in the interests of the ‘war effort’. (We found out years later that there was in fact plenty of metal with which to make Hurricanes and Spitfires, and that everyone’s gallant little sacrifices had therefore been unnecessary, so where did all the railings and old bicycles and broken saucepans go? There must have been millions of them. Since they disappeared so completely and permanently, one is tempted to think that the tidy-minded government, which constantly exhorted its subjects towards ever-sterner economies, had spent as much on disposal as it had on collection.)

I don’t remember anything about my first two teachers, except that Mrs Elves was ‘old’ and Miss Stacey was ‘young’. Well, they were to me. There was another, sort of ‘pretty old’, who was getting married – at twenty-seven. (Fancy embarking on matrimony as ancient as that! It was disgusting, or at the very least inappropriate.)

Then I was put in Miss Ellwood’s class. Miss Ellwood was a bit of a dragon, but I liked her because she let me tell stories to the class. When I was about 7 I had made the acquaintance of The Wind in the Willows, and for my 9th birthday my mother had bought me a copy of it. I still have that book, a treasured possession. It is a little the worse for wear now, not only because of the passage of the years, but because I have read it so many times.

I was a great believer in sticking to what you know and like. I liked Toad and Mole and Ratty and Badger, so I kept on reading about them. As a town boy I also enjoyed Kenneth Grahame’s evocation, knowledge and understanding of the countryside. The ‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ chapter puzzled me and I sometimes left that out, and I found the one about ‘Wayfarers All’ a trifle tedious. But the rest was sheer joy.

By the time I reached Miss Ellwood’s class – and I was only 9, if that – I had read it so often that I could quote chunks of it verbatim. So when she said one day, ‘Is there anyone here who can tell the class a story?’ I put up my hand and said that I knew one that might fill the bill, adding apologetically that it could be ‘a bit long’.

I don’t know whether Miss Ellwood was particularly generous with me or whether she thought she had found a tame raconteur who could be switched on any time she wanted ten minutes’ peace and quiet, but I stood there and waded through Mole’s spring cleaning, the ill-fated gypsy caravan trip, Mole’s fright in the Wild Wood and his meeting with Mr Badger, and Toad’s passion for motor cars, his imprisonment, his escapes and his triumphant return. It says much for Miss Ellwood’s iron class control that I was allowed to get through such a marathon. Perhaps they all simply went to sleep, I can’t say. Compulsive raconteurs are not always the best judges of the wakefulness and interest of their audiences.

It was Miss Ellwood who took us to see Lady Hamilton, and I thought it was absolutely smashing. Naturally, the more subtle nuances of the Hamilton-Nelson love affair passed me by, but I do recall the ‘N’ pendant round Emma’s neck when she met Nelson after his victory in Egypt over the French fleet. Miss Ellwood, who was sitting next to me, pointed out in a whisper (nobody dared make a noise in cinemas in those days) that the ‘N’ initial seemed particularly appropriate – for Nelson, Naples (where they met), Napoleon (Nelson’s enemy) and the Nile (the site of the battle). But when they got out of the hothouse atmosphere of the Neapolitan court and down to the serious business of fighting the French, it was all any healthy young filmgoer could ask for.

A suitable case for treatment. Photo by Emberson’s in Wimbledon Broadway. See p. 134.

Not knowing how the film’s version of the Battle of Trafalgar would stand up to modern historical research, I thrilled to the sight of the chequer-board-patterned men o’ war sailing in double line towards the French fleet, while a robust male voice choir sang Heart of Oak on the soundtrack. Nelson’s death fitted remarkably well with the version I had picked up in reading at school, right down to Laurence Olivier’s ‘Kiss me, Hardy’.

There were other scenes which stay fresh too. After the return of the English fleet to England, Hardy visited Emma at Merton to tell her the details surrounding Nelson’s death. Merton was not far from where I lived. Indeed, my first school was at Merton, where the local hospital was, and still is, called the Nelson Hospital.

Well, Hardy, played by Henry Wilcoxon, tried to tell Emma exactly what had happened on the quarterdeck in the minutes leading up to that fatal sniper’s shot from the French ship which was grappled alongside. Now, 9-year-old boys are not especially sensitive to, or sympathetic towards, human emotions beyond villains’ snarls or heroes’ grim smiles, but I remember being touched by Hardy’s devotion to his dead admiral. When his narrative reached the actual instant of the shot, he could not go on, and he broke down and wept.

Another touching moment concerned the long-suffering Sir William Hamilton, who tolerated the affair between his wife and a national hero with remarkable equanimity, and who possibly derived the more solace therefore from the priceless and unique collection of classical works of art which he had amassed during his years as ambassador at the court of Naples. The part was played by Alan Mowbray, who had spent years in Hollywood and British films playing pseudo-aristocrats, seedy villains and quack doctors. (You will have gathered that my visit to The King’s Palace with Miss Ellwood was by no means my first trip to the cinema.) To my surprise he showed emotional depths which I had never seen in him before and, when the news reached him that the ship carrying his beloved art treasures had sunk in a storm, the effect on him was shattering. You could see that it had knocked the very soul out of him.

Finally, a line of Emma’s. The film was told in flashback, beginning in a debtors’ prison, where Emma tells her story to the other unfortunate inmates. The last scene of her story was Hardy’s visit, to the house at Merton. When it faded, you were back in the prison again, gazing at Emma’s faraway face.

A crone leaned forward and said, ‘And then?’

‘There was no “then”,’ replied Emma. ‘There is no “now”.’

I have since found out that my enjoyment of this film, which may seem inordinate to anyone who has not seen it, or indeed to anyone who has, was shared by the famous. It was, I am led to understand, one of Winston Churchill’s favourite films.

After Miss Ellwood, I came under the instruction of the deputy head and headmaster in the top class. If Miss Ellwood had been a bit of a dragon, Mrs Penn was a positive tyrannosaurus. Ladies with their hair in buns always look forbidding, and since Mrs Penn’s job as deputy head, in charge of discipline, was to forbid most things, the impression was strengthened. She probably taught me very well in class, but my only other memory of her was getting the cane for something I hadn’t done.

That is not quite true actually, but the injustice felt was just as great. It was the fault of those lines. Or rather it was the fault of every child’s built-in compulsion to be first in lines. Yes, lines.

At the end of playtime, Mrs Penn came into the playground and blew a whistle. Everyone was expected to freeze on the spot. Amazingly, everyone usually did, at least for a second or two. Then they began furtive, stealthy movement. Why? Because they knew that the next whistle would be the signal to run to class lines, from which we would be despatched in regimental order to our respective classrooms.

Some psychologist ought to do research one day on why small children want to be first in a line which will take them into a school they profess to dislike and away from a playground they prefer. Similarly, another one should try to find out why teachers should derive such pride and pleasure from detaining children in statue-like immobility before summoning them to yet more rigid ranks. Their vigilance in detecting the slightest muscular movement in the playground was far greater than it was in detecting somnolence in the classroom.

‘Moving after first whistle’ was a crime far more heinous than rude words on the blackboards or tearing up books. It was a capital offence, like mutiny or sheep-stealing or arson in H.M.’s dockyards, and that meant the cane. At least it did in Mrs Penn’s book.

Well, you can guess what happened, or part of it; I ‘moved after first whistle’. So did several others. Mrs Penn, who had been looking towards the opposite end of the playground, suddenly whirled round. Everyone froze again. She had been just quick enough to sense that somebody had moved, but not to pinpoint individuals. So she did the next best thing.

‘Who moved?’ she snapped. ‘Put up your hands.’

I had moved, so I put up my hand. So did some other juvenile George Washington.

‘Come here!’

And we got the cane, right there on the spot. Talk about drumhead court martial and summary execution. No mitigating circumstances, no statements to be read in defence, no opportunity to incriminate accessories before the fact, no softening of sentence in return for full confession, no chance for the condemned criminal to say a few words. Nothing. Wallop!

It rankled for days; those deceitful little beasts who had (very sensibly) kept their mouths shut, or rather their hands down, got away with it. It was one of my first lessons in the appreciation of the great fact of life: that there isn’t any justice.

When Mrs Penn wasn’t in charge of us and behaving like the Queen of Hearts, we were taught by the headmaster, Mr Cooper. I thought he was a fine chap. He was tall, to us anyway. He wore a suit. He talked in level, measured tones. He knew how to smile, and when he ticked you off he didn’t lose his temper. He looked a headmaster.

It was from him that I received the only lesson I ever remember in drawing technique. One day he came in and showed us all about perspective and vanishing points. I have done a fair amount of drawing and painting since, and whenever I do anything requiring perspective I think of Mr Cooper. It’s amazing how much you can get away with in representational art with only a nodding acquaintance with vanishing points.

Round about midday some officious pupil stood at the end of the top corridor and rang a bell half as big as himself.

For lunch, we had several choices, and at various times I tried them all. Sandwiches, obviously, was one, but I didn’t take them very often because my mother was a firm believer in the three-good-meals-a-day philosophy for rearing children.

Then there were school dinners. Our school didn’t have any kitchens, and a tall aluminium van called a Mobile Canteen brought food in every day. Everything seemed to be stored in tall steel-can-like tea urns – stews, grills, roasts, pies, puddings – everything. The custard was the most memorable. The movement of the van had had the same effect on its contents as did the shaking of a butter churn on its load of milk; you could practically chop it off in slices, lumps and all.

For a while I took a sabbatical from school dinners and sampled the wares of the British Restaurant back home near the railway station, on the corner just opposite the allotments at the bottom of Durham Road.

I suppose British Restaurants were so called in order to convey to a rationridden, war-weary public the impression of good, solid, jolly, Merrie-England hostelry – you know, John Bull at his oak-beamed door, wearing a capacious apron, with a pint pot in one hand and a stable boy’s collar in the other. Good for morale. For the same reason, I should imagine, Winston rechristened the Local Defence Volunteers the ‘Home Guard’.

I don’t think Winston or any members of the coalition government would actually have sampled British Restaurant cuisine. If they had, they would have found it scarcely conducive to patriotism. It was self-service, no table service. Every possible cost had been cut, though at least the trays were wood, and the tables too. This was in the Golden Pre-Plastic Age, when the chief affront to good taste was humble bakelite. Tubular steel came along when they stopped using it to make Lancasters and 10-ton bombs.

At the counter stood numerous thick-armed ladies of indeterminate age who called everyone ‘dear’. They wore white overalls and had their hair done up in a sort of white turban. Turbans seemed the obligatory headgear for nearly all women in any kind of non-clerical work. Factory girls wore them with dungarees; food shop assistants wore them with overalls; bus conductresses wore them instead of London Transport peaked caps; and housewives wore them when they cleared their pavements of broken glass, spattered there by the blast of bombs. They were so universal that I became seriously concerned about my mother’s normality, because she didn’t wear one. I even asked her once to do so, in case anyone should think she was odd. The fact that she was neither factory girl, food shop assistant nor bus conductress, and that she did not spend her time sweeping up broken glass from pavements, did not entirely remove from my mind a vague feeling that she was somehow ‘different’.

Mind you, I could not honestly claim that she looked very much like those brawny ladies who dropped a couple of sausages on my plate, and then squeezed out two hemispheres of mashed potato with queer gadgets that I had seen used hitherto only for filling ice-cream cornets. ‘Pudding’ was always rice or semolina, or, worse, sago, with perhaps a dollop of jam in the middle if you caught them on a good day. (Another mystery of wartime was that the types of food you disliked, hated or abhorred never seemed to be rationed or in short supply.)

All that, plus a cup of tea, was about 9d (4p), so I suppose you couldn’t grumble. I wonder what Egon Ronay would have made of it?

Finally, I tried a fourth type of lunch. My mother had left her work in London when she brought me back from evacuation and took a job near Wimbledon so that she could get home earlier for me. It was a film-processing firm, known as the Roll Film Company, and it operated in Nursery Road, not far from where the original Wimbledon Tennis Championships used to be played. She arranged for me to have lunch in the works canteen. To get there, I might therefore have trodden ground once graced by the headband, billowing skirts and overhead smash of the legendary Suzanne Lenglen.

More prosaically, I took a 604 trolleybus from outside my school to Darlaston Road, crossed over and walked down to the rented house that served as offices and canteen to the employees of the Roll Film Company. I sat down to the table with Beanie and Connie, who were 15, and Miss Martin, who was, well, a bit older, and Mary, who was fierce and forbidding and pretty ‘mature’, and Mr Beeston and Miss Harris who were quite ‘old’, and I minded my P’s and Q’s with Mr Barker, the boss, who lived up to his name and was about 104.

Lunch was cooked by Mrs Ames, who, when she was not ladling out food or washing up, spent a lot of time adjusting the curtain over the sink, or wiping the window over the sink. In order to do this she had to stand in the sink. This feat she could not perform without lifting her leg, and I mean lifting. She could not raise her right leg into the sink by itself; she used to put her hands one either side of her right knee, and literally lift her leg into the sink. Then she grabbed hold of something and hoisted herself into a standing position in the sink. Why she didn’t place a chair in front of the sink, get on that and step across I don’t know. I was too polite to ask. I don’t remember what Mrs Ames cooked, but I do remember her lifting her leg into the sink.

I had time after lunch to flip through the current issue of the Daily Mirror on the sideboard, and make myself au courant with the latest adventures of Jane and Belinda on the comic page. A new strip had started about a chap called Garth who, for reasons of the plot which now elude me, had gone back in time to a Stone Age existence and had befriended a frightened-looking, nubile young blonde whom he had christened ‘Dawn’. The adventures he had with the ‘Prof.’ were good reading fare, but I thought the ‘Dawn’ bits were pretty wet. (It always disgusted me to see how often professional writers, who ought to have known better, regularly spoiled rattling good stories with soppy love bits.) A final glance at the film adverts to note that Roxie Hart, with Ginger Rogers, was now showing in Gaumont-British cinemas in north-west London, and would, therefore, after a week in cinemas in north-east London, appear in south London, and I had time to walk to Darlaston Road to catch the trolleybus back for afternoon school.

If I sacrificed the Daily Mirror, Garth, and programmes at Odeons in north-west London, north-east London and south London, I could catch an earlier bus and have time for ten or fifteen minutes’ cricket with Georgie Winters, Ken Stibbards and Jeffrey Wale and the rest, with a tennis ball and a wicket chalked on a wall of the air-raid shelters.