Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

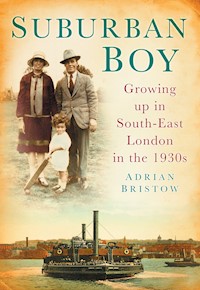

Adrian Bristow came not from a working- or upper class background, but from that great unsung mass - the lower middle-class. Adrian Bristow describes what it was like to grow up in the 1930s in an ordinary suburban family. He enjoyed a childhood radically different from that experienced by children today: so much that he took for granted has disappeared completely or changed utterly. What Adrian took for granted becomes, on reflection, quite extraordinary and it is the essence of this difference that he has recaptured in this book. Illustrated with a wide range of family photographs and images of south-east London, Suburban Boy will be a highly enjoyable read for anyone who delights in memoirs of childhoods past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUBURBAN

BOY

Growing up inSouth-East Londonin the 1930s

ADRIAN BRISTOW

First published in 2012

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Adrian Bristow, 2008, 2012

The right of Adrian Bristow to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8024 4

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8023 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Introduction

One

Boundaries

Two

Parents & Relations

Three

Auntie Walters

Four

Early Days & Army Ways

Five

A Mixed Infant

Six

House & Garden

Seven

Close Relatives; Closet Relations

Eight

Under Taurus

Nine

Balls & Wheels

Ten

Parks & Commons

Eleven

Collectables

Twelve

Sea & Sand

Thirteen

Jaunts & Jollities

Fourteen

Sacred & Profane

Fifteen

Evening Entertainments

Sixteen

In a Large Pond

Seventeen

Transports of Delight

Eighteen

The Wine Press

Nineteen

Growing Pains

Twenty

The End of the Beginning

Epilogue

‘Is this bilge,’ he asked, ‘to be printed?’

‘Privately. It will be placed in the family archives for the benefit of my grandchildren.’

Laughing Gas, P.G. Wodehouse

INTRODUCTION

‘Bow, Bow, ye lower-middle classes!

Bow, Bow, ye tradesmen, bow ye masses!’

Iolanthe, W.S. Gilbert

I am a child of my time, and that time, though I can hardly believe it, is now over seventy years ago. I was brought up in Woolwich, a suburb of London, in the 1930s and I have tried to conjure up what it was like for a boy growing up in a specific stratum of society, a lower-middle-class home, at that time. So my book may be seen as something of a postcard of a vanished age from a boy’s perspective. A vanished age indeed! The landscape, the buildings and the parks I remember are still mostly there but the people have gone, their pre-war way of life has altered dramatically, and the nature of the boyhood I enjoyed has disappeared forever.

The momentous events of the 1930s – the Depression, the abdication, the rise of Hitler and the coming of war in 1939 – formed the background to a boyhood which I never thought of as anything other than unremarkable. But, looking back, it now seems quite remarkable in many aspects. Before the memory of the vivid scenes, figures and places of my early years fades, it is the matter-of-fact nature of my childhood that I wish to convey. Fortunately, many people who lived through that decade are still alive and I hope this memoir, particularly the humdrum domestic and social detail, may awaken echoes of a half-forgotten yet treasured past. For my younger readers – well, those under seventy – if distance does not exactly lend enchantment, then perhaps it might arouse a certain curiosity about the way many of us lived then.

At present, recollections of childhood before and during the Second World War have rarely been so popular. Everywhere, gates to the secret gardens of memory stand unlatched and articles and slim volumes of early times remembered rattle from the presses. They seem to be of two types. There are reminiscences of childhoods spent in tranquil villages under the downs, with memories of golden days in great houses and of timeless afternoons bathed in sunshine. Sturdy little figures in pinafore dresses and floppy white hats stump across buttercup meadows to the brook; small boys and large trunks are dispatched by steam to unbearable prep schools. And all the while, the grandfather clock in the echoing hall ticks off the hours of childhood.

The other kind reveals, in uncompromising detail, grim tales of childhoods between the wars among northern back-to-backs or the decaying tenements of the capital. Here, amid poverty of mind and pocket, and draining unemployment, life is punctuated by sordid dramas played out in squalid kitchens. Often the only redeeming feature is the figure of Ma or Mam, monumental among the ruins. It’s all good material, of course, for the inevitable first novel. My recollections, however, are of a different kind, for, as far as I can discover, there are few memoirs dedicated to growing up in an essentially lower-middle-class home in London during the 1930s.

I should like to stress that my family was undeniably lower-middle class, though of recent working-class origin. My father was not a manual worker or a skilled craftsman, but essentially a clerk, a white-collar worker, whose wife did not go out to work, even part-time. He was part of that upwardly-mobile movement of future owner-occupiers (via the building societies), some of whose children were to become firstgeneration grammar school pupils and university graduates. Such families (I am generalising now) were respectable, respectful, conformist, mainly conservative, patriotic, class-conscious and not overly concerned about religion. And, if some of those characteristics happened to be shared with the middle-class, so much the better for unspoken aspirations. Consciousness of class lay heavily upon the lower-middle classes and our lives were shaped in insidious ways by its subtleties. I make no apology for emphasising this because it was a major factor in social life.

I realise that for most adults under seventy, the 1930s are as remote, funny, savage and inexplicable as the Edwardian era of my parents was to me. To them, the 1930s means, essentially, the Depression, with mass unemployment and the rise of Hitler – and not much else. This view of the decade appears deeply embedded in the popular mind and has been created over the years partly by folk memories of the past and partly by contemporary newsreels, newspapers, television documentaries and political rhetoric. Because some would consider my childhood was spent against a tawdry backcloth, perhaps I might be allowed to enter one major caveat. The grinding poverty and despair caused by mass unemployment that characterised large areas of the country did not extend, by and large, to the south of England. I saw virtually nothing of the effects of the slump in my part of London, or where we travelled in Kent and Sussex, but I was, after all, only a young boy, fully occupied with my microscopic affairs. In fact, for many it was a time of rising living standards, while the country continued to enjoy a prolonged period of social peace. There was relatively little crime against either person or property, and people remained law-abiding, tolerant and deferential. There also existed a proud sense of national identity, buttressed by victory in war (though achieved at grievous cost in life) and enhanced by a still extensive empire.

I was fortunate; but I was not exceptional in this. Most of my friends spent happy childhoods in close-knit families in modest houses. There was always enough to eat and we were properly dressed and shod. Our parents played for hours with us at home, and showed us the wonders of London on days out. They introduced us to castles and cathedrals during our summer holiday at the seaside; the summers in the 1930s were long, warm and sunny – vide Wisden passim. We had strong, if slightly bemused, support at school, though there was no question then of parents becoming involved in our schools or actually visiting them. Apart from taking us to the mixed infant departments when we first started and collecting us later in the day, contact stopped at the school gates. Pocket money was minimal but we can never remember, though hard-up, feeling hard done by. Ours was a small, intimate world of home, neighbourhood and school, with few clouds on our horizon.

In retrospect, there seems to have been a singular richness about my early years, although it was certainly not apparent at the time. The richness was derived partly from the loving web of relatives and quasirelatives which enmeshed and protected me, and partly from a variety of experiences, many of which had vanished long before my own children were growing up. Thus my children and grandchildren know very little of the routines and domestic arrangements that dominated my life at school and at home. They are unaware of the interests that absorbed my seemingly endless leisure, or of the curious games and activities my friends and I pursued. Again, many of these pursuits have disappeared forever, while others seem hopelessly out-dated.

Two last comments. I realise that, like all children, I absorbed certain values, prejudices and attitudes from my parents and their contemporaries. Both my parents were born in 1896 and grew up in the Edwardian era and during the First World War. They were as much prisoners of their childhoods as I am of mine. Thus their childhood experiences inevitably affected my upbringing and coloured my life for some years. I have tried, not always successfully, to avoid making comparisons, either implicitly or explicitly, between then and now. Instead, I hope that my readers will draw their own conclusions without being buffeted about the head with the faded splendours of times past.

ONE

BOUNDARIES

‘Forget the spreading of the hideous town;

Think rather of the pack horse on the down,

And dream of London, small and white, and clean,

The clear Thames bordered by its gardens green.’

Prologue, The Earthly Paradise, William Morris

Unlike most of those who write about their childhood, I cannot pretend to have either an accurate or a detailed memory. Certain incidents, some significant at the time, others of so little consequence I cannot understand why I should have remembered them, stand out vividly, but they do so against a blur of happy domestic activity. I cannot recall even fragmentary conversations from my early boyhood and it irritates me that I can no longer remember the exact details of some scenes I wish to recapture.

Luckily, I do have an accurate visual memory for people, landscape and townscape, for houses and streets, for shops and parks. I can conjure up in my mind’s eye what people looked like and what they wore, helped here by a collection of old family snaps. A child of my time, I write the word ‘snaps’ automatically.

During the few years I am attempting to recall, characters move in and out of focus, and they grow or diminish in importance at certain stages. When one is young, familiar adults rarely alter or grow older, although some mysteriously vanish from the scene, either from natural causes or by courtesy of Pickfords. It is usually the grandparents, the ‘nanas’ and ‘grandpas’, or elderly friends of the family, who first bring awareness of death. Such losses, limited as they are in number and spread over several years, do not cause great sadness and are soon forgotten in the excitement of growing up.

I have tried to be as accurate and as honest as possible in my recollections. I am encouraged by the fact that as I write about my early years, as I exercise and rack my memory, incidents and details I had overlooked and people whose existence I had long ceased to be aware of begin to emerge from the fog of forgetfulness. As the mist thins, much that has remained unremembered takes shape once more and the events of over seventy years ago come into sharper relief.

I grew up and went to school in that part of south-east London bordering the Thames which embraces Woolwich, Plumstead and Shooter’s Hill. Woolwich, although I did not realise it then, is a town of some historic importance, having been the home of great military and naval institutions. Its royal dockyard, established in Tudor times, was the first, and for centuries the principal, dockyard in the country. The Great Harry was built there in 1562 and the Royal George in 1751, but shipbuilding ceased in 1869 and the dockyard became a military store depot.

A little way downriver was the vast expanse of the Royal Arsenal, some 1,200 acres devoted to the sinews of war. The Arsenal developed gradually from the time of Queen Elizabeth I but it grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, reaching its peak in terms of output and employees during the First World War. Guns, shells, torpedoes, small- arms ammunition and wagons were produced in huge quantities in its workshops to fuel the battles on the Western Front. The Arsenal also included experimental laboratories and extensive practice ranges on the nearby marshes. All the various engines and components of war were designed, tested and manufactured there. In the 1920s and ’30s, the Arsenal and the dockyard provided much of the manual and skilled-engineering work in the town. In many families, son followed father into employment there and both places were regarded locally as rest homes for those fortunate enough to enter their gates.

The main gates of the Royal Arsenal.

Powis Street, Woolwich.

I became aware early on that Woolwich was a military centre of distinction. It was the headquarters of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and the town was dominated by its great barracks, hospital, playing fields and parade ground. The RA also possessed its own garrison church, theatre, museum (the famous Rotunda) and the specialist buildings needed for men, horses and guns. Beyond this immediate area stretched the expanse of Woolwich Common, dotted with various military installations, including gun sheds, a repository, barracks and a stadium where the famous Woolwich military tattoo was held. Nearby was James Wyatt’s Royal Military Academy, cousin to that at Sandhurst. It was here, behind its long, castellated façade, complete with miniature white tower, that engineering and artillery officers were trained. It was the alma mater of Woolwich’s most famous son, General George Gordon (he was born at 29 The Common in 1833), more colloquially known as ‘Chinese’ Gordon and later, Gordon of Khartoum.

As one might expect, many of the streets and squares in Woolwich were named after military heroes, and one heroine of the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars. Unthinkingly as a child, I walked along Nightingale Place, Wellington Street, Hill Street, Beresford Square, Raglan Road, Paget Street and Cambridge Road. Other roads had military echoes: Academy Road, Ordnance Road and Artillery Place. Indeed, a street map of Woolwich is a useful primer of military history.

I suppose Woolwich was best-known nationally for its free ferry. This was originally established in the 1880s, and when I first knew it, there were two paddle steamers, the Will Crooks (MP for Woolwich from 1903–21) and the John Benn (a former chairman of the LCC). In the 1930s these ferries carried about 20,000 passengers and 2,500 vehicles daily.

The Woolwich Free Ferry.

Shooter’s Hill.

As the town spreads southwards, the ground begins to rise steadily towards Plumstead and to the imposing ridge of Shooter’s Hill, over 300ft high, along which run the Old Dover Road or Watling Street. It was up Shooter’s Hill that the Dover Mail lumbered in the mud on a Friday night in late November at the start of A Tale of Two Cities. The ridge is the southern boundary of Woolwich and Plumstead; beyond were the suburban deserts of Eltham and Well Hall. To the west, past Woolwich Common and the Royal Artillery barracks are Charlton, Blackheath and Greenwich. To the east, Woolwich merges with Plumstead and the long expanse of Plumstead Common points towards Abbey Wood and Erith.

The area was, and still is, fortunate in possessing a number of those ‘lungs of London’ – namely public parks and woods. Besides Woolwich and Plumstead Commons, there was Shrewsbury Park and Eaglesfield, Oxleas Woods, Jackwood, Castlewood and Crown Woods. Several of these woods and parks lie on the slopes and crest of Shooter’s Hill and had been acquired by a far-sighted council to prevent development and to preserve them for the public. My favourite, Shrewsbury Park, though not quite at the top of Shooter’s Hill, commanded a panorama of London River and the City. On clear days, looking westwards beyond the shining bends of the river, you could see the dome of St Paul’s eight miles away, the tallest building in the City, dominating the horizon. Immediately below lay Woolwich Reach; I remember seeing the splendid sight of the Thames sailing barges, with their brown sails and distinctive rig, plying up and down the river. To the east, the Thames wound its way out towards the estuary and the Channel, with the tall chimneys and bulk of the Ford factory at Dagenham looming in the distance.

Although we moved twice before 1939, I still grew up in an area that was only about a mile-and-a-half square. In fact, the part in which I spent most of my boyhood was even smaller, yet it managed to encompass the myriad experiences of childhood. It is strange, in retrospect, to realise how very limited it was. You never know an area so intimately as that of your childhood. Growing up slowly, moving out, on foot, from the centre, you learn an intricate network of streets and lanes and commons, much as a young policeman learns his beat. But when you move away, grow older, become a car owner, you never know your new district in this detailed way. You drive to work or to the shops along routes that hardly ever vary. You rarely walk for pleasure in towns or in the suburbs. Now, of course, children are no longer able to play in the streets or roam the district, as we once did. Within my boundaries I knew every street, lane and alley, and all their names. I had dawdled, run, chased and been pursued through them. I had walked to school, to the shops and to the parks. I knew every path and track on the commons and in the woods. I knew the names of all the shops, stalls and most of the public houses. As Ratty knew his river bank, so I knew my territory in Woolwich and Plumstead.

TWO

PARENTS &RELATIONS

‘Ere the parting hours go by

Quick, thy tablets. Memory!’

A Memory Picture, Arnold

I want to tell you something of the background of my parents and their families so that you can understand the influence they had upon my childhood. My father was born in 1896 in East Grinstead, a small market town in Sussex, and lived there until 1914. His father, George, was a carpenter and the family had been established in the town for many years.

My mother and father.

They lived at 88 Queens Road, a pleasant three-storey semi-detached house built of a soft red brick, about fifty yards from the cricket ground in nearby West Street. It was a narrow but substantial-seeming house, with a small back garden that ended treacherously in a shin-high wall and a steep drop into the cemetery. The front door, approached by a flight of stone steps, was always kept freshly whitened and rarely used. A passage sloped down the side of the house and led round to the back door, outside which stood the mighty mangle. When I first saw the living room, it contained a gas stove (the house was lit by gas) and a shallow stone sink, a kitchen range and a pantry in the corner by the back door. There was a large, pine kitchen table and dresser and the brick floor was covered with coconut matting. The rest of the ground floor consisted of a long, unlit subterranean passage leading from a corner of the living room and terminating in a lavatory raised high upon a concrete step – a throne indeed. The most fleeting of visits through there was a candle and matches job. Halfway along this passage, a curtained aperture on the right led into a low-ceilinged workshop-cum-storeroom with an earth floor, lit by a semi-basement window. Here were all kinds of objects, the bygones and discards of two generations which I enjoyed turning over. Covered in dust and hopelessly jumbled together were strange jars, sticks, boxes, tools, wire, rusty tins, wood, parts of bicycles, deck-chair frames, broken umbrellas and various kitchen utensils exhausted by years of waiting to be repaired.

On the first floor were two rooms. The rear room was a highly respectable but immensely uncomfortable sitting room, dominated by an oval painted photograph of my grandmother and a studio portrait of my father, a private in the Royal Sussex Regiment. The front room was a kind of parlour with no defined function and hardly ever used. Indeed, the back room itself only seemed to be used on Sunday afternoons for polite teas or if there were visitors. When we used to visit my father’s family, we always sat and had our meals at the kitchen table downstairs but, then, we were ‘family’.

My grandparents on my father’s side are but shadowy figures. My grandmother died in 1932, when I was six, and I only remember a stout immobile figure in an armchair by the kitchen range. My grandfather died three years later, his thick walrus moustache, like the smile on the face of the Cheshire Cat, is the only feature about him which has endured. Considering his prowess as a cricketer, I find it surprising that he left no indelible sporting mark upon me. He was a well-known local cricketer, turning out regularly for East Grinstead, where his bowling was a great asset. He had also played for Sussex Colts but he never actually played for his county.

Myself as a baby with my parents.

While still a boy, he played in a local youth team at a time when the Australians were touring England. Each member of this team was nicknamed after an Australian cricketer and my grandfather, no doubt on grounds of alliteration and a common Christian name, was called ‘Bonnor’. George Bonnor was a bearded giant of a man, 6ft 6in tall, known as ‘the Australian Hercules’, and a tremendous hitter. This sobriquet stuck so fast that it was subsequently attached to all male Bristows. I can remember my father being greeted in the town with ‘Hey up, Bonnor’ more than once. There is a pleasant story about Bonnor. Unlikely as it seems, he attended a supper at which Augustine Birrell lectured on Dr Johnson. After this daunting introduction to the works of a writer of whom he had never heard, Bonnor said, ‘If I weren’t Bonnor the cricketer, I should like to have been Dr Johnson.’ To which Birrell replied that if Johnson had been present that night the great man would have preferred Bonnor’s conversation to that of the literary critics gathered around the table.

There were seven children in the family: four boys, of whom my father (christened John Henry but always known as Jack) was the second, and three girls. All his brothers, George, the eldest, Jim and Harold, married but they produced only one son between them – Alan, George’s boy.

Family group.

Of my uncles, George was a fitter employed at the Arsenal. He and his family lived on the Well Hall estate and we saw them from time to time. ‘Brother Jim’, as my father facetiously called him, lived in a small, un-modernised terrace house in West Street opposite the cricket ground. He drove the town’s dustcart and was also a part-time fireman – but more of Jim later. Harold was the youngest of the family and I saw little of him as a child. He became a joiner and, after marrying, lived a little way out of East Grinstead at North End on the London road. So, we did not always see him when we called at Queen’s Road.

My father’s three sisters were quite dissimilar. Bess, the eldest of the family, kept house after her mother’s death and never married. She was an ardent supporter of the Methodist chapel at the corner of West Street and a source of scarcely-suppressed merriment in a family not renowned for Sunday observance or subtle humour. Sad to say, Bess was a trifle plain with a rather heavy, mournful face. She was, however, undoubtedly a good woman. Alice married Charlie Payne, a member of the Payne tribe related to and living near the Bristows. Alice (Alley) and Charlie lived a couple of doors away in Queen’s Road and we usually paid a brief call on them when visiting no. 88. After her marriage, Alley carried on working at a local solicitor’s office and continued there, after Charlie died, until she retired, having completed fifty years service. Nell, the youngest, was my favourite. She was a tall, rosy-faced, well-built woman, lively and full of fun with a country woman’s earthy sense of humour. I am surprised she never married because she must have had her chances, as they say, but perhaps her sense of humour got the better of her at the critical moment. She left school at fourteen and worked for over fifty years in a babylinen shop in the town. Bristows are nothing if not long-serving! She had a quick, accurate ear for dialogue and an appreciation of the quirks and quiddities of her older relations and the eccentrics in the town. On our visits, she needed little encouragement to regale us with a string of anecdotes from her repertoire.

My mother’s home was Brighton. Born in 1896, she was christened Elsie (though usually known as Else) and was the eldest of seven children, five girls and two boys. They were a close, happy and loving family and lived at 44 Totland Road, a street of small terraced houses demolished after the Second World War as part of a redevelopment scheme. Her father, Harry Potter (to whom I now realise I bear a striking resemblance) was a tailor’s cutter and fated to become, in 1913, one of the first road casualties. Walking in town, he stepped off the pavement to let some women pass and was struck by one of the new motorbuses. He suffered a broken hip and died a few days later in hospital, aged forty-two, leaving a wife and seven children, six of them under fourteen. Being quite unable to provide for her family, my grandmother (known to me as ‘Nana’ – all grandmothers are thus known in our family) was forced to see her children split up. Her two small sons, Charles and George, were despatched to Spurgeon’s Orphanage in Stockwell; three daughters, Phyllis, Gladys and Hettie, went to live with relatives in Brighton while Dorothy (‘Dot’), who was rather a sickly child, stayed with her mother. My own mother, who had left school at fourteen, was already in service and away from home.

Roy’s christening in 1928. I am standing on the left, dressed to kill.

It is a tribute to Nana and to the character of her children that they overcame these disadvantages and made their way successfully in the world. Charles became a self-employed accountant and George a store manager. My mother and her sisters all went out to work and, except for Gladys (‘Glad’), eventually married. Glad joined the Liverpool Police and afterwards transferred to the probation service and worked for many years in Cannock and Eastbourne. Auntie Glad was by far my favourite aunt, a tall, attractive, competent woman; it was always a mystery to us why she never married. I dimly recall whispers or half-heard rumours about a romance long ago with a naval officer that sadly came to nothing, but that was all.

Nana was one of nature’s survivors. She had always been a ‘bit of a lass’. At one period she and Harry had worked for a time in the evenings behind the bar of a club in Brighton. They were a pleasant, happy-go-lucky, gregarious couple with many friends. Nana, although not conventionally pretty, had bright brown eyes, a ready smile and a bubbling sense of fun. She loved a joke, enjoyed a drink, liked a game of cards (though she was a shocking loser) and took an active interest in the horses. Despite the sadness and poverty of her early married life, she was always remarkably cheerful and full of fun – I loved her very much.

I always became excited when Nana was coming to stay with us, for by this time she was my only grandparent. As soon as she came through the door, my first words to her, almost before she took her hat and coat off, were, ‘Will you play cards with me, Nana?’ And she unfailingly did. Together we played endless games of knockout whist, pelmanism, sevens and beggar-my-neighbour, with Ludo and snakes-and-ladders in between for a change. Throughout, Nana remained lively and amusing, and never for a moment did she give me the slightest inkling that she might have preferred to be doing something else.

My mother was a pretty young woman, 5ft 5ins in height, slim and with naturally wavy dark hair. She had an oval face, large brown eyes and neat, regular features. She was quiet, warm-hearted, capable and energetic but perhaps a little too submissive for her own good. Apart from a period during the latter part of the First World War when she worked as a conductress on the Brighton buses, a miserably cold job in the bleak midwinter, she spent her working life in service, first in Brighton but mainly in London until her marriage. You might say she remained in service after her marriage, too, because until her death she waited on my father hand and foot. This was not considered at all unusual at this time, for necessity and tradition meant that wives had to keep the breadwinner in the field. When he returned at night, exhausted by his labours, she had to be there to cherish him and cook for him, reserving the choicest morsels for his plate. This is how it had always been; daughters copied their mothers and so the pattern continued.

With my father and grandfather.

My mother’s time in service had given her, as it gave to so many young women, a distinct refinement. She had seen life in upper-class households at first-hand and she had absorbed certain standards of speech, dress and manners. She had learned how households were organised and managed and she had acquired a wide variety of domestic skills. She tried in her quiet, modest way to introduce a little of the fruits of her experience into her own house, not always without success. Occasionally, when we were alone together, she would talk about her time in service, prefacing her remarks with, ‘I remember once when I was with Lord Joycey . . .’ Sometimes she would come out with sayings she had picked up, such as, ‘You can always tell a lady by her feet and a gentleman by his neck.’ Her background sometimes led to differences with my father, who had not been exposed to her advantages, but he was sensible enough to realise his good fortune in securing such an attractive, competent wife. Theirs was a useful partnership, as he worked hard to secure his place on the lower-middle-class rungs of the ladder of life.

My father was a slim, dark-haired man, the same height as my mother, with an open, pleasant face and a ready smile. I think it is fair to say that my father was regarded by his own family as the one who had ‘got on’ – a view he shared with them. He was not a skilled craftsman like George or Harold, or a member of the dustcart team like Jim, but a white-collar worker. He was a clerk, a dark-suited employee, paid monthly, who started at 9 a.m., worked sitting down, and enjoyed a non-contributory pension. He was a man who wrote a fair hand and kept records, interviewed the undeserving poor, made calculations and handled money. He had not only served abroad during the First World War but he had left East Grinstead and moved to London. Invested with the aura of the big city, he tended to patronise his relations in East Grinstead and referred to them quite shamelessly as country bumpkins.

Because of the nature of his work, he established himself early on as something of an authority upon the life and habits of the London poor. If he stressed their shortcomings, I suspect it was partly to point out what a smart and able chap Jack was. This was acceptable within his family but slight tensions sometimes arose when he met my mother’s relatives. Although they had had an unfortunate start to their lives, they were of a much more formidable mettle than my father’s family. Even at the modest level at which they lived and worked, they were unwilling to be patronised. They considered my mother to have done quite well for herself, though my father’s amour propre would have been wounded if he had known that he was regarded by her family as a bit of a country bumpkin himself. Certainly, when in his mid-twenties, my father was a lively fellow, a young man with a fund of jokes and tales, mainly derived from his army service. Jack, in fact, was rather a lad and my gentle mother always referred to his being ‘the life and soul of the party’.

My father was a slow but steady and reliable worker (a pace bequeathed to all his four sons by their father), and his domestic life revolved round his home, his wife and son. He rarely had a drink and was never a man for pubs and clubs or for the dogs and horses. He was mildly interested in football and cricket and he occasionally turned out for his office cricket side. He was a kind and affectionate father, genuinely fond of children, and he always had plenty of time to spare for me.

Theirs was a successful marriage. I was never conscious as a child of any tensions between them and I certainly cannot remember any ‘words’ or rows. We were, simply, that not unusual institution – an ordinary, happy family.

THREE

AUNTIE WALTERS

‘Come to me, come to me! When the cruel shame and terror you have so long fled from, most beset you, come to me! I am the relieving officer appointed by eternal ordinance to do my work; I am not held in estimation according as I shirk it.’

Our Mutual Friend, Charles Dickens

M