Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Without aiming to be a survival guide, romance or autobiography, Sunbathing in Siberia manages to be all of them and none. Told completely from the Trans- Siberian and a series of Russian jets, this is the story of a young British poet, who, after becoming engaged to his translator over 3500 miles east, embarks on a journey into the very heart of Siberia to marry his fiancee. However, in place of the desolate wasteland he expected to find, Michael discovers the side of Siberia little known outside of Russia. After 30 years of British rain, Michael has finally to learn the art of sunbathing, in the last place on Earth anyone would think to take a pair of flip-flops. With little knowledge of post-Soviet Russia, or its language; and without any survival skills, Michael has to adapt to the Siberian way of life. As Russia struggles to find its new identity, Michael too is forced to recreate himself, while finding the tools needed to live with parading nuclear missiles, wild bears, and a host of extreme dangers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

PART I

Aeroflot Flight SU0242. March 29th 2011. London – Moscow

Point of No Return

A Very Long-distance Courtship

Trans-Siberian. March 31st 2011. Moscow – Krasnoyarsk

Transaero Flight UN158. April 26th 2011. Krasnoyarsk – Moscow

Pushkin Square

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

People are People

Knowing Where to Walk

Khrushchev’s Permanent Thaw

The Red Army Strikes

Aeroflot Flight SU0241. April 16th 2011. Moscow – London

Moscow, Fridge Magnets, and Tactical Nuclear Weapons

Easter in the Dacha

Aeroflot Flight SU781. July 20th 2011. Moscow – Krasnoyarsk

PART II

Aeroflot Flight SU778. August 17th 2011. Krasnoyarsk – Moscow

Ira

Superstitions

Domovoi

Aeroflot Flight SU247. August 17th 2011. Moscow – London

London’s Burning

Aeroflot Flight SU781. December 19th 2011. Moscow – Krasnoyarsk

Summer at the Dacha

PART III

Aeroflot Flight SU241. January 16th 2011. Moscow – London

Winter in Russia

The Mormon Invasion

Christmas, Vodka and Snegurochka

Red Tape

Aeroflot Flight SU2571. May 28th 2012. London – Moscow

Red Paint

White Paint

Visas and the Capitalist Mclympics

PART IV

Aeroflot Flight SU1481. August 25th 2012. Krasnoyarsk – Moscow

Summer, Liberty and Leprosy

Propaganda

Line of Sight

What is Good for a Welshman is Great for a Siberian

The Uninvited

Krasnoyarsk 26, the Secret City

Dachnik

The Invited

Aeroflot Flight SU2578. August 25th 2012. Moscow – London

PART V

Aeroflot Flight SU1481. December 12th 2012. Krasnoyarsk – Moscow

Papa in Siberia

Rambo

North Korea Invades

Hypothermia

The Italian Way

Stamps, Stamps, Stamps and More Stamps

The Abominable Snowman

HIRAETH AND THE APOCALYPSE

EPILOGUE – ONE YEAR IN SIBERIA & COUNTING

Acknowledgements

Further Acknowledgements

Copyright

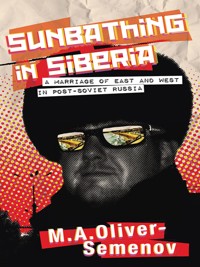

Michael Oliver-Semenov was born in Ely, Cardiff, but now resides in central Siberia. Since ditching his career as a banking clerk in 1997 he has published words and poetry in a plethora of magazines, anthologies and journals worldwide, includingBlown,The Morning Star,Orbis,Ten of the Best,Wales Arts Review,Mandala ReviewandInk Sweat and Tears. He divides his time between growing vegetables at his family dacha, teaching English and writing forThe Siberian Times. http://thepoetmao.webs.com

SUNBATHING IN SIBERIA:

A Marriage of East and West in Post-Soviet Russia

M.A. Oliver-Semenov

To everyone living in Russia,

everyone living outside of Russia,

and everyone in-between.

PART I

Aeroflot Flight SU0242. March 29th2011.London – Moscow

Jaffa Cake: A round soft sponge type thing topped with orange coloured jelly and covered in a thin layer of chocolate. How was anyone supposed to know a Jaffa is an orange when it doesn’t say so on the box? It said ‘Jaffa Cakes’, meaning that Jaffa was either the name of the company or it was an actual fruit in its own right, like a kiwi or a banana. Or it could have even been a totally made-up name like rock cakes, which to my knowledge contain no rocks at all. How was I supposed to know that Jaffa wasn’t a country, or a person? Where I grew up there was a local man called Jaffa; and although I suspected it wasn’t his real name it was the only name anyone knew him by; and besides, people had all sorts of weird names, especially in the food world, like Captain Birdseye and Mr Kipling. It was a basic logical deduction that led me to believe that, much in the same way Mr Kipling had invented a type of cake, Jaffa Cakes were invented by someone named Jaffa.

I was in my late twenties when I discovered that this wasn’t true, that Jaffa was, in fact, a type of orange from a place named Jaffa. I listened to my friends talking about some poor bugger who had admitted that he didn’t know what a Jaffa was. And to my newly acquired middle class, it was something they could laugh heartily about. They couldn’t imagine living in a world where people had no experience of Jaffa oranges being anything other than a slice of gooey jelly placed on top of a cake that came in packs of twelve and was nice enough, and affordable enough, that your mother bought a pack every Friday when she did the shopping.

Why is a Jaffa Cake a Jaffa Cake and not an orange cake anyway? An apple pie is just an apple pie. It’s not as if a pie baked with Cox’s apples is called a Cox Pie, or a Golden Delicious Pie or Pink Lady Pie. Why not orange cake? Because Jaffa sounds posher, I guessed. Though the only Jaffa I ever knew was the fella who apparently, back in 1985, could get you cheap tracksuits that ‘fell off the back of a lorry’. Took me a while to figure out what that one meant too. For many years I wondered why they didn’t just make lorries with better locks or load them with less stuff before they travelled.

This was, of course, a distraction. It was all I could think of to keep myself from going crazy. As I took the last of the Jaffa Cakes from the box in my rucksack and stuffed it into my mouth, my mind slid slowly back into panic. There was one question and one question only, rolling around my brain like a ball in a pinball machine, causing me to shudder every time it hit the forefront of my mind. Although it was madness – real madness – I couldn’t help but wonder: ‘Was she going to eat me?’

Point of No Return

When the doors to the plane were closed and we were taxiing for runway, butterflies began to have twins in my stomach. Or perhaps it was more of a panic attack. It was my first flight alone. I couldn’t hear anyone speak English and all the other people on the plane looked decidedly Russian. Dark thoughts began to enter my mind, pooling like drops of water from a leaky tap. Before I left Wales a helpful friend of mine had shown me an article where a Siberian woman roasted her husband on a barbeque and gobbled him up. There were plenty of other horror stories online about British men deceived by Russian honeytraps, left penniless and passport-less after being beaten and robbed. In these stories vulnerable men were usually lured over by hot women who secretly worked for organised gangs or Russian mafia.

Being of moderate intelligence I wasn’t altogether convinced I would be eaten by Siberian cannibals, but still, I was afraid. It was completely irrational and a bit cowardly, but while I had nobody to talk to and knowing there would be few people who could understand me once we reached our destination, my mind played a few paranoid tricks on me. I even started wondering whether Nastya worked for the KGB and wanted to ensnare me so I could be used to spy on the UK. In hindsight I can see that it was fear of the unknown and nervousness over our impending wedding that caused such silly thoughts, plus I had hardly told anybody the real reason why I was heading to Russia. I didn’t know what I would do if Nastya somehow failed to meet me in Moscow. I also didn’t know the Russian word for help, or any other Russian for that matter.

Over the four hour flight I managed to turn my fear into excitement and reminded myself that Nastya wasn’t likely to eat me or sell me as a sex slave to the mob. During one weekend in Paris, while out walking in broad daylight, we had been stopped in the street by two young people who tried to con me out of my money. It was Nastya who didn’t lose her nerve, grabbing me by the arm and forcefully pulling me through the con-artists to the safety of a café. It was Nastya who had seen me safely back to Gare Du Nord station, knowing that my sense of direction was rubbish. I knew that she loved me. I knew from our first meeting in Paris in January 2010.

We had met at the station and hurried back to our hotel where we made love clumsily as two people do when they make love for the first time. Afterwards, while Nastya had a shower, I sat at the edge of the bed and looked out over Paris at night. I was overcome with a sadness that seemed impossible to get past; I was sad that we had so little time together, that we had to part so soon after we had just met, that we lived so far apart from each other and that it would be a struggle to make our relationship work. Nastya seemed to sense this and, without me even noticing that she had left the bathroom, came and held me. In that moment she kept me from falling into myself. It was the most important embrace of my life. I don’t know how long she held me for but most of my troubles and internal battles left me there and then. Knowing this, it was crazy to think even for a moment that she could wish me any harm, or look at me like I would taste good with potatoes and tomato sauce.

A Very Long-distance Courtship

I was born Michael Anthony Oliver, or Little Mike, which is what my parents and sisters liked to call me when they wanted to piss me off. This only lasted for the sixteen years it took until I left home and then, after inheriting my mother’s genes, I became big Mike; 6ft, slim and with hair that couldn’t decide if it belonged on top of a hedgehog or on Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry. As a conscientious young man I did my homework, left high school, and went on to A-Levels in college, only somewhere along the line something went wrong. I didn’t go to university. Instead I found myself working for five years in a high street bank as a mortgage underwriter and general office clerk. It was there that I earned my new name. This is a hotly disputed point between my parents even to this day, but when I was born one of the two decided to give me my father’s name, word for word, including middle name. For a minute or so they had discussed calling me Mark, but this was thrown aside as my dad already had an estranged son by this name through a previous marriage.

At twenty, well after I had left home, I toyed with the idea of calling myself Archibald Lasalles, after the long distance runner from the 1981 filmGallipoli, starring Mark Lee and Mel Gibson. In school, those who didn’t like football were made to run long distance through country lanes to the Greendown pub a few miles away, and back again within the hour. At the same time, in history class, when we were asked to re-enact a scene from history, I chose to be Archie Lasalles on his final run over the front line in World War I, so the name seemed a good one to keep for myself, though it proved a bit mouthy. After two weeks I ditched it.

When I started at the bank in 2002, the boss who was forever kissing my arse for some reason, called me Chairman Mao, as M.A.O. were the initials I signed letters with. It stuck. I didn’t hate my birth name, Michael is after all the name of some archangel, and a keyring I bought when I was on a school trip at the age of five had said ‘Michael: who is like the lord’, but having the same name as my father had left me feeling as though I didn’t have an identity of my own and without this I struggled to live as a human being separate from him. However, sat on that plane, my birth name, printed on my ticket was one of the few things I had to identify myself as myself.

My sister Mab, who was born Michelle Anastasia Oliver, had suffered the same identity crisis as me; she was after all another M.A.O. After running through every stage of the education system with flying colours she had gone to live in Japan in 2001, to make a living teaching English while learning the fine art of karaoke.

In March 2006, after years of drudgery, self-loathing, boredom and despair caused by working in a bank, I received a phone call from the pub next to work. It was Mab. I left the office early and told my boss I would have a very long lunch. My sister looked confident; she had brighter eyes and was a shadow of the self-doubting person I had known in previous years. After a few pints she pronounced she was going to be a famous writer and poet, and asked if I would care to be her warm up act. Soon after that I quit my job and started writing full time, taking on a few menial jobs to keep the wolves from the door. Three years later, Mab prepared a show named D-Day and invited me to take part in it, alongside a small army of other poets and writers. As an anti-nationalist she had the idea that we would read to a bilingual Welsh/English audience on St David’s Day while ridiculing nationalism. Many years earlier, while explaining to a friend of a friend my frustration at having failed my Welsh A-level, and how hard it was to integrate with the fluent Welsh-speaking society, she had joked that I may as well have learned Russian; in preparing for the D-Day show I remembered her words and considered them further. I decided to deliver my entire performance in Russian.

Using a series of social networking sites I was able to identify many people who had the words ‘Russian translator’ as part of their history or interests. After looking at a few candidates and not having the slightest clue who to go for, I thought best to choose one entirely at random. After a brief introduction and some begging, Anastasia Semenova, a telecommunications engineer with a background in literature and translation agreed to translate my poem for free. Not only had I found a translator but I had also found my future wife.

Every day after work I would switch on my computer just to speak to Anastasia (Nastya to her friends) on Facebook Chat. Nastya, being in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, was seven hours ahead; when it was 5 p.m. for me it was midnight for her. We never had much time to talk but we cherished every minute. At first we found friendship in the fact we had both recently come out of difficult relationships. I had dated a woman from 2006 to 2008, and this union had ended badly. Nastya had lived through a similar relationship, in almost the same time frame. So we confided in each other about how we felt, which felt easier than talking to our other friends because of the very fact that we were two people who hardly knew each other. We were entirely different from one another – perfect opposites – however our friendship strengthened as we were both heartbroken, very lonely, and yet very determined in a pact to steer ourselves away from our past lives and live as independently as we could. This seemed like a fine idea, only the more we talked of independence the more we drew together; and the more we designed our own way in the world the more our desires collided. Although neither of us wanted to be romantically involved with someone else, we couldn’t help but forge a romantic bond. Exchanges of personal philosophies led to an exchange of photographs. Exchanges of photos led to exchanges of feelings. At twenty four, Nastya looked very much like a young Sophie Marceau, and although I was four years older, I still had a brilliant head ofDirty Harryhair to speak for me. Plus I was a cyclist with a cyclist’s frame. Though we had few things in common, besides our ruined love affairs, our fondness for one another grew to the point we couldn’t pass a day without a phone call. By Christmas time, we were in love, although I had also become unemployed, couch-surfing the living rooms and kindnesses of friends and relatives.

We had known each other for nearly a year and yet we hadn’t actually met face-to-face. In November, to pay for our first meeting I took a part-time job working early hours in a supermarket. Nastya decided that our first encounter would be in Paris in the New Year, on January 7th, which just happened to be Russian Christmas Day. As it was winter and a particularly harsh one at that, the snow and ice had limited the Eurostar travel to only two trains a day. News coverage reported hourly how so many hundreds of people were stranded in St Pancras, London, and it was advised not to travel if you didn’t have to. On the morning of the 7th, I left Cardiff for London on the National Express. An hour after we had crossed the Severn Bridge, it was closed due to falling ice. When I arrived at St Pancras, it was heaving, the queue of people went from the ticket office, through ten bendy queue-dividers, right down to the end of the building. I waited for hours and was the last-but-one to board the only train that afternoon.

I arrived in Gare Du Nord at about 8 p.m. Paris time. My French was terrible (still is), and I couldn’t find Nastya anywhere. When I asked a police officer where the main exit was he simply shrugged his shoulders and mumbled something French. Nastya and I phoned each other in desperation, each claiming the other was by the exit of the building, which of course wasn’t true; I was by a small, little-used exit for smokers. After much panic Nastya found me and gave me a huge hug, her big brown eyes full of tears. She had arrived in Paris a few hours earlier and had already studied the underground system. She led me to Line 4 where we took the train all the way to Porte d’Orléans, Montrouge, at the end of the line on the South Bank. She had booked us a double bed for the weekend at the hotel Ibis. Needless to say we didn’t see much of Paris, although we did venture out once or twice to see the Eiffel tower; because it was winter, and an unusually cold one, there was snow everywhere which made it more romantic. It was as if Nastya had brought Siberia with her.

Paris became our meeting point throughout 2010 as Nastya couldn’t enter Britain by any means. In order to obtain even a simple British tourist visa Nastya would have needed to make the equivalent of 30,000 roubles (around £600) a month. At this time she made around 17,500 roubles (£350) a month. I on the other hand was prepared to visit Russia but didn’t have the money. It is ironic that while Nastya held a well-respected job as an IT technician, was reasonably well paid where Russia is concerned, was qualified as a translator and engineer and was a trained pianist, her movements were restricted by global politics and the economics of the day. Whereas I, a poorly-trained unofficial nobody and self-appointed poet, could travel anywhere, provided I had some dosh. Even a full-time, minimum-wage job would have afforded me enough money to visit Russia. However, in 2010, the hotel Ibis in Montrouge, Paris, was our second home on occasional weekends. By our next romantic getaway in Paris we even had our own favourite restaurant, which although we don’t remember its namecanbe found by taking the underground to Boulevard St Michel and walking two streets in from the river in the direction of the Eiffel tower. At the point you are completely lost, the restaurant is on the left.

It was early on in our affair that we decided to marry. Our long-distance courtship was taking its toll on us; I guess all people in these kinds of situations find it hard. Not only that but I couldn’t really say I had a home to go to and because of the global economic crash there was little chance of me finding a regular, decent job in the UK. British immigration law states that I would need full-time employment and a permanent residence in order for Nastya to be allowed to live in the UK. Pigs might fly by the time that happened and so the only option available to us was for me to move to Russia.

It turns out that finding someone who wants to marry you isn’t the hardest part of getting married. For a British citizen to marry abroad one needs a lot of forms. Firstly you must apply for a Certificate of No Impediment to Marry (CNIM). Once you have this it needs an Apostille (this is a stamp from the Foreign Office based in Milton Keynes). A standard Russian tourist visa at the time had to be applied for forty-five days before the intended travel date which prevented me from booking really cheap flights. Once I applied, I had to wait around two weeks for a decision. This was to allow the FSB (Federal Security Service formally known as the KGB) adequate time to investigate me (the application was very long and asked if I had any ‘special skills’ or military training).

When I had my passport back, I thought I was in the clear. Research on several Russian travel websites soon informed me that when I arrived in Moscow I would still need to get everything translated and stamped again. Then all my documents, both original and translated, would need to be presented to an International Wedding Court. Worse than this I read that we could only be married a month or two months after application, which would have been impossible with a single month’s visa; although the same websites stated that the wedding courts would likely accept bribes to make it sooner. Determined that we wouldn’t be separated by bureaucracy, or economics, I left for Moscow with a suitcase full of warm clothes, and a rucksack loaded with Jaffa Cakes.

Trans-Siberian. March 31st2011. Moscow –Krasnoyarsk

The doors to all the wagons of the train opened simultaneously, and a number of heavyset, extremely intimidating female guards stepped out in black greatcoats and grey ushankas (classic Russian trapper’s hat). Our passports and papers were checked and we boarded. The engine itself wasn’t anything like I had expected. I had been hoping for some great big steam engine, instead it was a large industrial one. Like a green brick on wheels.

There are three different classes of tickets on the Trans-Siberian. The first and most expensive is a compartment all of your own. The second is a compartment of four bunks – two lower bunks that convert into beds, and two upper bunks which are always beds – and third class, which I am told is six bunks to a compartment. We had chosen second class. I wasn’t actually aware of the etiquette and so as soon as we entered our compartment I sat on the seat opposite Nastya. This seemed only natural, but not long after I had sat down, a large, muscular Russian man entered and gave me The Look. I was sat in his seat, which would also double as his bed, so I changed sides quickly.

Sat next to Nastya, with our knees pressed against the tiny table in the centre, it was hard to imagine how anyone could travel third class. But people do, and often. In Russia, because of its size, it’s normal for people to commute to meetings via two, three, four or sometimes eight-day journeys. Our compartment, second class, felt like a sardine tin and for the next three days that sardine tin was home. There was a dining cabin on board the train, although eating there would have required leaving our bags with a complete stranger. Having anticipated this situation, we had bought a picnic – some sausage meat, a large pack of cheese, some Brie, a loaf of bread, a pack of pastrami and a few sachets of herbal tea – from a half decent supermarket we had found earlier that morning, which surprisingly sold a wide selection of Western produce.

When it was time to prepare our meals, which involved cutting our bread and cheese on theitsy witsytable, our travelling companion, although large and scary, turned out to be the perfect gentleman and would always leave for a walk up and down the train. I regret not learning his name or plucking up the courage to thank him for his good manners and generosity before he left the train for good. The Trans-Siberian is a popular tourist attraction and so it was normal to find a Brit on the train with an extremely poor grasp of the Russian language. Therefore our companion only communicated through Nastya, and only to make polite conversation or to ask if we would like to share his beer. The afternoon was long – from the small window we could only see pines and birches morning and night – except for a few stations, which all looked alike. There was no shower facility and the toilet made a high-pitched sound when flushed that hurt our ears if we weren’t quick enough to cover them. Anyone who takes that train across the whole of Russia is not only going to have severe cramp by the end of their trip, but is likely to smell as bad as a wet dog that has been rolling in his own poop.

Despite all this, our first day passed without incident. However, as we hadn’t got to know our travelling companion yet, after he procured a 6-inch Bowie knife from his boot to cut his meat in the afternoon, I found it near impossible to sleep that first night. Nastya had brought her own knife to cut meat but it was only an inch long. I knew this would have been of little use in defence against a burly Russian who carried a blade big enough to chop off my head in one fell swoop. Lying there on my bunk above Nastya’s as we were hurtling further into Russia in the dead of night I was struck by fear and panic. With the ceiling of the wagon so close to my head I occasionally reached up, put my palms against it and pressed myself deeper into my bunk, as if this would somehow make me safer. As the hours went by I began to doze slightly, my mind filled with images of Moscow.

As the plane touched down in Sheremetyevo airport, I could see it was going to be hard to dispel the stereotypical view of Russia I had come to know from Hollywood films. A bleak sky mirrored the dirty snow surrounding the airport; the blanket of grey-white absorbing the airport sign’s blood-red glow without a trace of reflection. I was met at Sheremetyevo by Nastya, who had taken the Trans-Siberian to Moscow three days earlier and had arrived that morning. She had already booked us a double bed in a hostel where we planned to stay for two nights. I had arranged to meet an up-and-coming Russian poet in Red Square the following day and we also needed to get documents translated. To give you an idea of the scale of Moscow, it took nearly four hours to travel from the airport to the other side of the city (it takes four hours to travel from Cardiff to Heathrow Airport, via National Express). Moscow could be a country all of its own. It is a vast maze of roads and underground train stations. I had left the UK on a four hour flight at around 1.15 p.m. GMT and arrived in Moscow at about 8.30 p.m. because of the time difference. After travelling across the capital and checking into our hostel it was close to midnight, so there was little time for anything other than sleep.

My first day in Moscow had begun with a trip through the underground to a translation office in order to have my CNIM, Apostille and passport translated. We left photocopies of my documents there and went for my first lunch in a Russian café. The food was worse than anything I could have imagined. The jacket potato I ordered was not potato, but Smash, smothered onto a rubbery potato skin. The sausage was not actual meat, but rather some kind of Spam-like meat substitute. The bacon wasn’t actual bacon but a rolled-out Spam-substitute with bacon colouring. I discovered that all the crap you wouldn’t even feed to a stray dog is sold to humans in Russia; not only that, but many of the products available are also out of date. Even the packets of cigarettes I bought should have been binned months earlier. I assumed this was due to the global economic crash of 2007 but Nastya assured me that the decline in quality of products had begun in the late nineties.

After our delicious Smash potato meal, Nastya lead me through the underground once more to meet the poet Nikitin on Red Square. Evgeny Nikitin is another person I had met online while I was looking to make good connections with Russian poets. He was one of the founding members of the Moscow Poetry Club as well as being the newly-appointed editor for the very famous Soviet and Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Earlier that day, Nastya and I had visited Red Square so that I could take a few photographs. As we stood around admiring the scenery, we had heard screams. When we turned to see what the commotion was we saw people running. From between two buildings what looked like a white wall of ice – or huge cloud of white dust from a Hollywood movie – came pouring out over the Muscovites. It had taken only a few seconds to reach us. The wall was, in fact, a sudden blizzard made of heavy chunks of snow and hail. We fled like everyone else and took shelter in one of the subways.

As soon as Nikitin had joined us, we headed straight for a coffee bar of Nikitin’s choosing, in case another storm hit us. Over English tea with milk he told me the story of his first collection of poetry. It was sold in a shop for contemporary books not far from where we were. In previous months, the militia had requested that this shop be closed down because some of the content of the books they stocked were deemed subversive and because it was also a meeting place for modern poets and political thinkers. The shop wasn’t shut down due to some legal technicality; however a week later it was mysteriously set alight by persons unknown, and all published copies of Nikitin’s collection perished. The shop had since been refurbished and so Nikitin offered to take us there. I wish I could remember the address but it’s probably for the best that I cannot. The shop itself was off a main road, down an alleyway, through a side door, up three flights of stairs, along a corridor and on the other side of a large steel door. When we arrived Nikitin couldn’t show me any of the books he had wished to, as there was a meeting of political thinkers and poets who were clearly in the middle of an important debate. We listened for five minutes before deciding that it wasn’t safe to stay there. Had the militia stormed the building, had they asked for my papers and seen I was British visiting on a tourist visa, I could have been arrested, interrogated and/or deported. Instead Nikitin led Nastya and me back to the main street where we parted company and walked in opposite directions. It was already early evening and the cold was beginning to bite. Before going back to our hostel, Nastya and I went to a mini supermarket to get a few things necessary for a light supper. We were both surprised to find the shop almost completely empty, except for a few cans of a red fizzy drink made in the Caucasus and a few large bottles of water. We left with two bottles of the fizzy red stuff only to be disappointed later.

When we arrived back at our hostel at around 10 p.m. I noticed that there were many militia on our street, an unusually large number of them, and they seemed to be coming from a building across from ours. Nastya informed me that we were actually sleeping across from their headquarters. Militia (pronounced mee-leet-see-ya) are everywhere; they are partly police, partly immigration authority and partly intelligence service. They are the first thing you notice when you step off the plane and they remain omnipresent for the rest of your trip. I had learned from the Russian visa company I used that they have the power to stop and search anyone. It is said that if they find you without your passport and papers to hand, and you do not have sufficient money to bribe them, you can be deported. They are to be avoided at all times. I did not sleep so easy that night knowing there was an army of them across the street.

We left early the following morning, carrying my luggage which weighed around eleven kilos. When travelling in any foreign country I think it’s always best to travel light in order to avoid any unnecessary delays, plus it’s easier to run away if you get into trouble. After picking up our newly-translated documents in the centre of Moscow and purchasing two tickets for the Trans-Siberian we made our way to Yaroslavsky train station, north east of the city centre. This was actually the most frightening part of my journey. Yaroslavsky station was teaming with all kinds of unsavoury people. They swarm around you under the pretence of wanting to sell you something while they take mental notes of where your money is most likely hidden. Not only that but there were around two hundred militia, standing around like demigods, laughing among themselves, automatic rifles loosely slung over their shoulders like harmless rucksacks; some swinging their weapons around like a child would swing a toy. Never have I heard that little voice inside of me shouting so loud ‘Get out of here! Get out of here now!’ We couldn’t get out of there right away though. We were to wait on the platform while the train had its interior cleaned. I needed a cigarette. I took out my tobacco and papers to make a roll up and was quickly scorned by Nastya, who chose that moment to inform me that nobody in Russia smoked roll ups; people would think I was smoking drugs and would likely inform the militia. I looked around. A few people were watching so I finished my smoke as casually as I could and hoped for the best.

We hadn’t had to walk through any barriers to get to our platform. Absolutely anyone could come and stand next to the train. Among obvious passengers there were several babushkas (old women) without luggage, just brown parcels in their hands. They approached everyone on the platform and, one by one, begged us to take their parcels for them. Nastya refused bluntly in a very harsh tone. I knew why, of course. Although they seemed to be normal old ladies, who were trying to get a stranger to do them the kindness of delivering a parcel for them because they hadn’t the money for postage, there could have been anything in those packages. With Nastya’s best Siberian ‘Go away or I will get nasty’ tone and a wave of the hand, they left us to bother someone else. This reminded me of a story Nigel, a friend of mine from Cardiff, had told me weeks before I departed. A Russian friend of his who wanted to attend some sort of conference in Bulgaria was only allowed an exit visa if he would agree to deliver a package for the KGB. However that incident was during the Soviet years, and as I wasn’t actually bargaining for anything myself, I’m confident those Yaroslavsky babushkas weren’t working for the secret service. They had a look of desperation on their faces and were dressed in worn-out winter coats, rubber shoes that looked decades old, and head scarves that didn’t appear anywhere near capable of keeping the cold out. Some had even been close to crying.

By the afternoon of our second day on the train I was too tired to be afraid anymore. I had forgotten to bring a toothbrush and so Nastya asked the wagon guard to bring me a travelling kit. This consisted of a tiny toothbrush, a small sachet of toothpaste, a bar of soap, a tiny folded towel in a sachet, and a pair of paper slippers. On the Trans-Siberian, like anywhere in Russia, it is considered rude and unhygienic not to wear slippers, even if you’re the kind of person who walks in your socks. Regardless of not being a slipper person I was glad of the comforts that were included in the kit and wore my paper slippers every day.

It should also be noted that while on this extremely exciting and frightening train journey I carried two mobile phones. One, an expensive all-singing all-dancing touch screen thing which had more functions than I can count; and the other, a five pound supermarket mobile, which made calls and sent texts. While travelling through four time zones from Moscow to Krasnoyarsk, my flashy phone went all flashy. It told the wrong time constantly, changed the time as and when it fancied, and in general seemed in a state of panic. However, my cheap mobile updated the time when we broke through into a new time zone, welcomed me to my new destination via text, informed me of the new tariffs and offered numbers for emergencies relevant to that area. This is the phone I still use today. It doesn’t sing or dance, or allow me to check emails, or locate my GPS position, but it doesn’t panic; and while you are travelling through Russia and are likely to panic, you need a phone that will remain calm.

Every few hundred miles, the train needed to stop, either at a station to pick up and drop off passengers, or at a docking area to refuel, take on water and fresh supplies of food. These stops are crucial for leg stretching and getting some fresh air because the windows in the sleeping compartments don’t open. Even though the large female wagon guards would dress down while the train was in motion, each time it stopped they would always stand tall, just to the side of the wagon entrance, wearing great coats and ushankas, looking official.

At these stops, some of which seemed miles from anywhere, there were often babushkas that looked no different from those I had seen in the train station, waiting with goods that they hung on strings under their shabby winter coats. I didn’t buy anything from them but was glad and sad each time I saw them. I admired their tenacity and will to keep on going, but was sad that they had to endure what appeared to be a very tough way to make a living. When I awoke on the morning of day three, our travelling companion had vanished. Instead there was a different Russian man on the top bunk opposite mine. This one was much uglier than the first and didn’t seem to care much for our company. Thankfully he got off in the late afternoon in Novosibirsk and wasn’t replaced by anybody. Our next station and final destination was a little less than twelve hours away, and so Nastya and I got to spend the rest of Day Three alone. As I was feeling slightly sick and undernourished we ordered some soup and a plate of chips from the dining cabin, only too happy to take our order and deliver it. When the tiny portions of food were delivered it became clear why they were so happy. It appeared that food from the dining cabin wasn’t any different from café food, in that it was undercooked, and the portions were only fit to keep a starving rat alive a few more hours. However, I was glad for the soup, although it tasted like boiled mayonnaise. Nastya told me this was a throwback from the early 1990s when people added mayo or sour cream to their food to make it seem more than it was.

It was after my hearty and delicious meal that Nastya and I got to live the James Bond/Natasha Romanova experience, and have sex on a train (see Ian Fleming’sFrom Russia with Love). I can’t be too explicit about this as I wish to avoid embarrassing my wife, but what I can say is that sex on a train is great and must be considered by all horny tourists who take the Trans-Siberian. Undressing a gorgeous young Russian woman, while travelling at high speed through the wilderness of Siberia is a huge turn on, and knowing the wagon guard lady might enter at any moment to empty the bin or hoover the floor just heightens the adrenalin level that little bit more. It has to be said that by the end of Day Three, I didn’t care where we were going, which country we were in, or how many big scary Russians were near. This was good because the following day I had to meet my parents-in-law to be, both likely to be big scary Russians.

On the morning of Day Four the train began to slow at 5 or 6 a.m. Krasnoyarsk time and we were woken by the radio. Each cabin had a speaker in the corner by the window, which until then was used only to announce stations, and how long we would be stopped. On that morning they were playing a long romantic song, sung in English, called ‘My Krasnoyarsk’, which was both lovely and appropriate because we were about to stop at Krasnoyarsk. We brushed our teeth quickly, gathered and packed our things into my bags and watched out of the window as the train slowly ground to a halt. The view was unlike any other so far. Krasnoyarsk was a large city surrounded by dachas (wooden houses) and, to the south and west, these were shadowed by snowcapped mountains. For Nastya this view was commonplace since she had lived in Krasnoyarsk all her life, but for me it was breathtaking. As I stepped off the train I saw a large black steam engine parked on a concrete platform – a memorial perhaps for the time when the Trans-Siberian had been more romantic.

Transaero Flight UN158. April 26th2011.Krasnoyarsk – Moscow

Though it cost all the money that had been gifted to us after our wedding, Nastya came with me to Moscow on the Easter Monday. This was unnecessarily extravagant, but she had insisted, and as we had no plans for a honeymoon it seemed like a good idea to be tourists for a day in Moscow. She didn’t want to be without me for a minute longer than she had to. I was glad anyway, because although Yemelyanovo Airport near Krasnoyarsk was apparently international, none of the announcements were given in English. Even Nastya had seemed confused over which plane was ours because there had been two flights leaving for Moscow at the exact same time, going to completely different airports. I knew that if I had been there alone chances are I would have ended up on the wrong flight.

Sat by the window, I watched as we charged down the runway into the early morning sky. Siberia felt so alien to me – all those trees, mountains and little wooden houses. It was hard to picture myself living there, though I had been a guest for a full month already. I didn’t know what the future would hold but I knew I would have to return. We had no other choice. There was so much to do and so many decisions to make. I wasn’t sure if I could make the transition to Siberian life.

Oblivious to my internal struggles, Nastya smiled. She was excited that we were travelling together, or she seemed to be anyway. Before leaving the apartment there had been a moment where she began crying, but she quickly stifled her tears for my benefit. I had done the same the evening before, lying awake on the bed while Nastya slept. My mind simply wouldn’t switch off. As tired as I was, sitting next to Nastya, who was now my wife, it seemed a shame to sleep. I wanted to remember every minute of our last day together. We said nothing to each other the whole time, but swapped occasional knowing glances. When she finally fell asleep, as I knew she would, I thought back over my time in Krasnoyarsk.

Pushkin Square

Stepping off the train onto land felt much like stepping off a ship. My body was undulating from three days and nights of rolling over tracks. It was hard to stand up straight without rocking back and fore. This sensation lasted for a few days. Poor Nastya had it worse as she had come to Moscow by train and returned the same way. We were met at the station by Nastya’s Aunt Olga who drove us to Nastya’s city apartment where she lived with her parents. Driving or being driven in Russia is a totally different experience from driving in the West. The roads are full of potholes, and when I say potholes, I’m talking the kind of pots you grow trees in. All the cars swerve and weave around both sides of the road to avoid falling into them. Not only that but they drive at speed. Russians remember the location of each pothole like Westerners remember the location of speed cameras and tight corners. When we arrived at the apartment I was closer to a state of panic again.

City apartments and residential areas in Russia look more like Beirut that anywhere else. The buildings are tall and rectangular and are constructed from large concrete block or really big red bricks. The block work, while mostly straight enough to keep a building up, was obviously constructed haphazardly. It is not unusual to see a brick wall, which should be the flat face of a building, full of small twists and turns. Build a wall out of empty boxes with your eyes closed, and you’re not too far away from pre-1991 Russian construction. The main courtyards of these buildings are mostly large concrete slabs that also appear to overlap and have big spaces in between for you to fall into. Everything seems thrown together.