Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

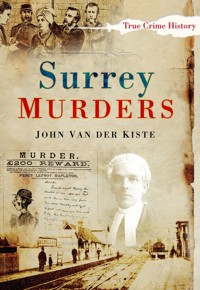

Surrey Murders is an examination of some of the county's most notorious and shocking cases. They include the 'Wigwam Girl', Joan Wolfe, who lived in a tent built by a Cree Indian Soldier before being brutally slaughtered; the infamous stabbing of Frederick Gold by 'the Serpent', Percy Lefroy Mapleton; the poisoning of the entire Beck family with a bottle of oatmeal stout, laced with cyanide; and the sailor butchered at the Devil's Punch Bowl, later immortalised in Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby. John Van der Kiste's carefully researched, well-illustrated and enthralling text will appeal to all those interested in the darker side of Surrey's history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 299

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Surrey

MURDERS

JOHN VAN DER KISTE

First published in 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© John Van der Kiste, 2011, 2012

The right of John Van der Kiste, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8393 1

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8392 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Also by John Van der Kiste

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

1. Murder at the Devil’s Punchbowl

Hindhead, 1786

2. Death on the High Street

Godalming, 1817

3. ‘You will know who did it’

Walton Heath, 1834

4. ‘What was done was never intended to be done’

Frimley, 1850

5. ‘This fatal rencontre’

Englefield Green, 1852

6. ‘Some slight excess of duty’

Haslemere, 1855

7. ‘Gave Katherine warning to leave’

Richmond, 1879

8. The Brighton Railway Murder

Near the Merstham Tunnel, 1881

9. ‘He spoke so kind to us all’

Godalming, 1888

10. Behind the Locked Door

Thames Ditton, 1903

11. The Body at River Row

Wrecclesham, 1904

12. The Merstham Tunnel Case

Merstham, 1905

13. The Deadly Bottle of Stout

Croydon, 1907

14. Death of an Unknown Tramp

Blindley Heath, 1910

15. The Hotelier and the Wireless Engineer

Byfleet, 1924

16. The Poisonings at Croydon

Croydon, 1928–9

17. The Cutt Mill Murders

Farnham, 1932

18. The Wigwam Girl

Hankley Common, 1942

19. The Doctor, the Pie and the Fruit

Milford, 1949

20. The Chertsey Shopkeeper

Chertsey, 1951

21. Death on the Towpath

Teddington, 1953

Bibliography

ALSO BY JOHN VAN DER KISTE

A Divided Kingdom

A Grim Almanac of Cornwall

A Grim Almanac of Devon

A Grim Almanac of Hampshire

Berkshire Murders

Childhood at Court 1819–1914

Cornish Murders (with Nicola Sly)

Cornwall’s Own

Crowns in a Changing World

Dearest Affie (with Bee Jordaan)

Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz

Devon Murders

Devonshire’s Own

Edward VII’s Children

Emperor Francis Joseph

Frederick III

George V’s Children

George III’s Children

Gilbert & Sullivan’s Christmas

Kaiser Wilhelm II

King George II and Queen Caroline

Kings of the Hellenes

More Cornish Murders (with Nicola Sly)

More Devon Murders

More Somerset Murders (with Nicola Sly)

Northern Crowns

Once a Grand Duchess (with Coryne Hall)

Plymouth: A History & Guide

Princess Victoria Melita

Queen Victoria’s Children

Somerset Murders (with Nicola Sly)

Sons, Servants and Statesmen

The Georgian Princesses

The Romanovs 1818–1959

West Country Murders (with Nicola Sly)

William and Mary

William John Wills

Windsor and Habsburg

AUTHOR’S NOTE & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book of Surrey murders is bound to come up against the conflicting boundaries of the old county and the new. In this account of twenty-one cases of unlawful killings committed between 1786 and 1953, I have taken ‘old Surrey’. This therefore includes the cases of Kate Webster in 1879, the Croydon poisonings in 1928–9, and the towpath murders at Teddington in 1953, which all counted as Surrey in their day although since 1974 they have fallen within the domain of Greater London. Two of the murders listed in this book are unusual in that the victim was never identified, and in one of these the main suspect was eventually acquitted. In five others the killer was never brought to justice, though in one of these the murderer escaped trial by committing suicide and in some, the police had a reasonably clear idea as to who the guilty people were.

Particular thanks are due to my wife Kim for her constant support, encouragement and assistance with reading through the draft manuscript; Hannah and James Cosgrave, Lois, Tim and Lara Caister, for assistance with photography; Nicola Sly for being always ready to help with advice and information whenever needed; Surrey Police Association, and John Cooper, for permission to reproduce images of copyright material; and as ever, my editors at The History Press, Matilda Richards and Beth Amphlett, for their continued help and encouragement.

Every effort has been made to obtain permission to reuse material which may be in copyright, and I would be grateful if any holders of relevant material whose rights have been inadvertently infringed would notify us, so that a suitable correction can be made to subsequent editions.

1

MURDER AT THE DEVIL’S PUNCHBOWL

Hindhead, 1786

One of Surrey’s earliest and most well-known murder cases concerned the fate of a man towards the end of the eighteenth century. Yet one element of mystery remains to this day: the name of the unfortunate victim.

On the evening of 24 September 1786 a sailor walking along Portsmouth Road stopped at an inn, probably the White Lion, at Mousehill, Milford, near Godalming. While enjoying a drink he made the acquaintance of three fellow sailors, Michael Casey, 42, Edward Lanigon, 26, and James Marshall, 24. Perhaps he recognised one of them as an old shipmate, or maybe he was on his own, and being an outgoing soul, relished some company before returning to sea. He had some money on him at the time, and while he would have been safer finding a coach to take him back to port before rejoining his vessel, he preferred to stop at an inn and pass the time with fellow patrons first. Sadly for him, they turned out to be anything but trustworthy.

Being in a generous frame of mind, he treated them each to a drink. Once they had finished, all of them walked to Thursley, where they stopped at the Red Lion, the last watering hole before a steep climb up the Devil’s Punchbowl, for more drinks. Again, he stood them all drinks. The inn was quite busy and several other people there at the same time later remembered having seen the four men together. Two of them were about to take the same road themselves.

Once the four men had finished, they set out on their way. The first sailor’s fate was almost certainly sealed by now. Casey, Lanigon and Marshall had probably been looking out for such a person. They may have decided beforehand to lie in wait for somebody whom one of them would pretend to greet as an old shipmate, lure into conversation and then help his companions to get their hands on his money. After having journeyed on foot a while, they reached a secluded spot and the three opportunists attacked their unwitting benefactor. They knocked him to the ground, stripped and robbed him, then mutilated him with their knives, butchering him so savagely that his head was almost severed from his body. Having taken his money and anything else of value, they dragged his body and tipped him down the slope of the Punchbowl.

The Red Lion, Thursley.

Assuming that he would not be found until they had had time to escape to another part of the country, or even overseas, the murderers made off in the direction of Liphook. However, they had been spotted by two other customers from the Red Lion, who noticed them disposing of the body. In order to make sure they did not suffer a similar fate, they remained under cover until sure the three other men had gone. They went to make certain the victim was dead and then returned to Thursley to report their terrible discovery.

A group of men got together and went in pursuit of the killers. The latter were soon apprehended at yet another hostelry, the Sun Inn at Rake, near Petersfield, where they had presumably gone to celebrate and spend their ill-gotten gains. A soldier, Thomas Doe, overheard their conversation, which gave them away at once, and arrested them. They were brought before Mr Justice Fielding of Haslemere, taken to the house where their victim’s body was lying, probably the Red Lion, and ordered to touch it. One of them was particularly reluctant to do so, as he was convinced that if the corpse was touched by its killer, it would immediately bleed. They were then committed to Guildford Gaol on a charge of willful murder of a person unknown, and taking from him goods to the value of £1 7s 6d.

The coroner then held an inquest in which he charged Casey, Lanigon and Marshall with ‘wilfully and with malice aforethought’ having struck ‘the said man’ with iron and steel knives valued at a penny each. They were tried at the Lent Assizes in Kingston, on 5 April 1787 on two indictments: for the willful murder of an unknown man, and for stealing a green jacket, a pair of blue trousers, check handkerchief, a hat covered with oilskin, two check shirts, a blue jacket, a pair of buckles, a black silk handkerchief, a blue shag waistcoat, blue trousers and other sundry items. All realised that there was nothing to be gained from pleading anything but guilty. The judge sentenced them to be hanged, and their bodies were to be left suspended in chains at the place where the murder was committed. Two days later the sentence was carried out on the summit of the hill.

Mary Tilman, a local woman, was among the large crowd who watched the execution. Her memories of the proceedings were passed down through the family and written down some years later. She recalled that once the executioner was satisfied the men were dead, they were cut down and put in irons (which did not fit properly) and then taken back to the Red Lion at Thursley. A blacksmith then came and ‘made the necessary alterations’. She was among those who went to the blacksmith’s premises to watch, and the crowds were so great that she was pushed against the bodies which lay on the ground, accidentally stepping on one of the heads. They were soaked in tar as a preservative, fixed into iron frames, and left to hang in chains for some time from an iron wheel at the top of a 30ft-high wooden post. The hill stood some 900ft above sea level and their bodies must have been visible from some distance as a grisly warning to others.

The Gibbet Cross at Hindhead.

Since then, the site has been known as Gibbet Hill. A memorial stone was placed at the spot where the murder took place, but it was moved by the turnpike trust to the side of a new stretch of road opened in 1826. For a while there were two stones, the original in its new position and a new one on the site of the killing. The latter had gone by about 1890, and in 1932 the original stone was restored to the old site. The inscription records that it was erected ‘in detestation of a barbarous murder committed here on an unknown sailor’ with the date and names of the murderers, and a text from Genesis 9:6, ‘Whose sheddeth man’s blood by man shall his blood be shed.’ A further inscription added to the base of the stone a hundred years later notes that the stone was renovated by James John Russell Stilwell of Killinghurst, a descendant of James Stilwell, who had originally erected the stone there shortly after the murder.

The unnamed victim was buried in the graveyard at the Church of St Michael and All Angels at Thursley. The grave lies to the north-west of the church, under a tombstone paid for by public subscription. An engraving to represent the murder surmounts an inscription which reads:

When pitying Eyes to see my Grave shall come,

And with a generous Tear below my Tomb,

Here shall they read my melancholy Fate,

With Murder and Barbarity complete,

In perfect Health, and in the Flow’r of Age,

I fell Victim to three Ruffians’ Rage;

On bended Knees I mercy strove t’obtain,

Their Thirst of Blood made all Entreaties vain

No dear Relation; or still dearer Friend,

Weeps my Hard Lot, or Miserable End

Yet o’er my sad Remains (my Name unknown)

A generous Public have inscribed this Stone.

The killing has never ceased to cast its spell over successive generations, and was immortalised in literature little more than half a century later. In The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, published in 1839, Charles Dickens wrote of two of the characters visiting Gibbet Hill and walking around the Devil’s Punchbowl:

Smike listened with greedy interest as Nicholas read the inscription upon the stone which, reared upon that wild spot, tells of a murder committed there by night. The grass on which they stood, had once been dyed with gore; and the blood of the murdered man had run down, drop by drop, into the hollow which gives the place its name. ‘The Devil’s Bowl’, thought Nicholas, as he looked into the void, ‘never held fitter liquor than that!’

2

DEATH ON THE HIGH STREET

Godalming, 1817

George Chennell was a much-respected tradesman in Godalming. From his premises in the High Street, he ran a shoemaking and leather business, and also kept a small farm nearby. A widower for some years, he and his housekeeper, Elizabeth Wilson, lived over the shop. He generally retired to bed at about 9 p.m., and Mrs Wilson an hour later. His son, also named George, was in his mid-30s and lived nearby. Separated from his wife, he tried to make a living at farming, but failed, and spent much of his time drinking in the Richmond Arms nearby. He usually took meals with his father at the latter’s house, but he often got into violent arguments with his father and used threatening language against him and Mrs Wilson. The elder Chennell was a mild and inoffensive gentleman, while his son had a reputation for being impulsive, aggressive and never satisfied.

At about 8 p.m. on Wednesday 10 November 1817, Charlotte Austin of the Little George, and George Woods, a baker who also lived in High Street, saw Mr Chennell Senior and Mrs Wilson as usual. They were probably the last people to see them alive. At about half-past seven next morning their severely battered bodies were discovered in the house. Mr Chennell lay upstairs on his bed in a room facing the street, while the housekeeper was lying on the kitchen floor downstairs. They were both dead. Both had had their throats cut and their skulls fractured. The warden, James Weale, checked the till in the shop area on the ground floor, which had been forced open and was empty. He found six £1 notes and 15s 6d in the dead man’s pockets.

Suspicion immediately fell on the younger Mr Chennell and his drinking companion, William Chalcraft, who had sometimes worked as a carter for the murdered man. Aged about 50, he had a wife and six children, but was separated from them. They were usually supported by the parish, while Chalcraft, like the younger Chennell, spent most of his wages at the bar. The younger Chennell’s lodgings and pockets were searched; two £1 notes were found, with bloodstains on them, as well as 15s 6d in silver. Both men had been seen in the alleyway next to his father’s house on the night before the murder at about the time it was thought to have taken place.

Guildford High Street, c. 1830.

That same Wednesday evening, Chalcraft was at the Angel Inn with one of his friends, Sarah Hurst. William Coombes, a waiter, saw them whispering together, and overheard her say sharply to him, ‘Hold your tongue, Chalcraft, I want to hear no more of it.’

Both men were arrested on a charge of murder and held in custody at the Little George. Sarah Hurst was similarly apprehended as an accomplice, as she had been seen alone in the alleyway, pacing up and down, evidently keeping a look out. When first questioned, she seemed to be trying to protect the male suspects, even implicating others in the crime, among them her own husband. While she was held in Kingston Gaol she had several fits which, it was said, ‘might have hurt her intellects.’ The Under-Sheriff, Mr Smallpiece, visited her at this time and reported that she was ‘very wild in her manner, and confused in her ideas.’

The trial of Chennell and Chalcraft was due to take place in the spring assizes of 1818, but had to be postponed because of the illness of a key witness. Both prisoners therefore spent about nine months in Guildford Gaol until the trial opened at the Guildhall on 12 August. As the doors opened, a large crowd of spectators surged through to come and watch the proceedings. Many more waited outside in the high street, ever hopeful that a few more might be allowed in. It was a hot day and the courtroom was so packed that at one point Mr Sergeant Lens, the judge, halted proceedings so that every possible window could be opened. Some of the witnesses’ testimony could be heard through the open windows by the crowds outside.

Mr Gurney opened the case for the prosecution, remarking in his opening address that ‘the horrid crime of murder had its graduations of atrocity,’ and in this case ‘it was aggravated when committed by the strong upon the feeble and unresisting.’ A servant had been attacked by the master, and an aged father by the son. Charlotte Haynes, landlady of the Little George, gave evidence to the court that on the night of the double murder, old Mr Chennell and Mrs Wilson had kept to their usual routine. The wall between both properties was so thin that she could hear everything which went on next door. Mrs Haynes had not been well that night and retired to bed earlier than usual, at about 9.50 p.m., but did not go to sleep until about 11 p.m. She did not hear Mr Chennell go to bed during that time, or indeed anything out of the ordinary, a fact which the prosecution seized on to suggest that the murders had probably been committed between 9 and 9.50 that evening. This was corroborated by another witness, an unnamed male passer-by, who said he had heard a scream, followed immediately by the sound of something or someone falling, as he walked past the house at about 9.30 p.m. Several other witnesses testified to seeing both the accused in the alleyway next to the house at about 9.15 p.m.

Mrs Hurst was also seen, pacing up and down. By this time she was no longer being accused as an accomplice, though she was a witness for the prosecution, albeit a rather unreliable one. Mr Gurney warned the jury that she was known to be ‘an infamous character’, and should not be believed unless her evidence could be confirmed by the testimony of others. She had been seen on the night of the murder following Chalcraft home, while Mr Chennell Junior went back along the High Street and back to the Richmond Arms, where he had been seen earlier that evening. He claimed that he had left the inn for a very short time at about 9 p.m., ‘to look after a woman’, returning so quickly that a tobacco pipe which he had left on a table was still alight. This testimony was not corroborated by witnesses from the Richmond Arms. One, the landlord James Tidy, said Chennell had been away for nearly three quarters of an hour, and on his return he had not continued to smoke his old pipe but was given a new one.

The two £1 notes in Chennell’s possession, one stained with blood, formed an important part of the evidence. He claimed that his father had given them to him on the Sunday. However, while he was drinking in the Richmond Arms earlier on the evening of the murder, he did not have enough cash to pay for drinks to the sum of 8½d. After 9.45 p.m. it was noticed that he had considerably more cash on him. Mr Gurney pointed out that although £6 15s 6d had been found in the dead man’s pockets, a till had been forced and was found empty and one of the banknotes was stained with blood.

Next, Isaac Woods, Constable of Godalming, produced the murder weapons. The first was a shoemaker’s hammer, sharp at one end, round and blunt at the other, and it had been used to inflict the head wounds on both victims. It had been found in a tub by John Keen, Keeper at Guildford Gaol, when he examined the murder scene on the Tuesday. Dr Parsons of Godalming considered that the head wounds, rather than those to the throat, had caused death in both cases, as their throats had been cut after they were dead. Constable Woods then held up a knife which had been found by Mrs Wilson’s body, still stained with blood. The knife and hammer were both identified as being the property of the deceased.

John Keen then gave evidence. Having taken Chalcraft into custody, he said that had found spots of blood on the right sleeve of the accused’s smock. It was not suggested in defence that any such spots could have been picked up when Mrs Wilson’s body was discovered by Chalcraft and John Currington on the Tuesday morning. When Currington, who worked as a farmhand for Mr Chennell Senior, arrived for work at 6.30 a.m. he found Chalcraft in the storeroom at the rear of the premises, adjacent to the stables. The door was open and Chalcraft was sitting with a corn sieve in his hands. Currington thought this was unusual as the door was not normally unlocked until his master was up. The key was kept inside the door of the front kitchen, and whoever collected the key had doubtless seen the bloodied and battered body of Mrs Wilson, lying on the floor near the door.

Currington prepared the horses for the day’s work, then returned to the back kitchen of the house for breakfast, while Chalcraft went home to eat. Neither went to the front kitchen. At about half-past seven Chalcraft returned, then he and Currington brought the horses out into the street. Currington told the court that he was surprised to see no sign of movement in the house. He and Chalcraft went indoors to check if everything was all right, but it remained quiet and nobody appeared. Chalcraft then went down the passage and through the cellar to the front kitchen. Currington then thought he heard him open the door into the room, and then shout up the stairs, as if calling for his master. Then Chalcraft came down the passage, saying nothing, and both men went outside, where Chalcraft rapped on the window of Chennell’s room with his long horse whip. They then went back indoors, both went down the passage together, opened the front kitchen door, and discovered Mrs Wilson’s body.

The prosecution claimed that if Chalcraft had entered the room the first time, when he was heard shouting up the stairs, he must have stumbled over her body. Chalcraft swore that he did not, but Gurney insisted he surely had, though what bearing this had on the question of his guilt was never made clear. Chalcraft gave his evidence in a clear voice, without hesitation. He claim he had not seen Chennell Junior since the Friday before the murder and had gone to bed at 9 p.m. on the night of 10 November. The witnesses, including Sarah Hurst, were either lying or mistaken when they said they had seen him in the alleyway that night.

George Chennell then repeated his account of his movements to and from the Richmond Arms that night, reading much of his evidence from notes he had made. He persisted in his claim that he had picked up the same pipe on returning to the inn. He had not seen Chalcraft since the Friday.

The judge’s summing up lasted about two and a half hours, and proceedings were completed shortly before 9 p.m. At the end of a long hot day, the jury took only three minutes to find the prisoners guilty of murder.

On the morning of Friday 14 August, a large crowd gathered outside Guildford Gaol, and just before 9.30 a.m. a wagon fitted with a platform and steps drew up at the main entrance. Chennell and Chalcraft emerged a few minutes later to step on to the wagon for their final journey to Godalming. The executioner sat in the wagon with a turnkey on either side of him. The Revd John West of Stoke-next-Guildford sat with his back to the horses, Chalcraft to his right and Chennell to his left. As the procession reached Godalming, it halted on the Lammas Lands, meadows on the banks of the River Wey. The gallows had been erected there within sight of Deanery Farm, which Chennell had once run but without much success. Crowds of thousands were thronging the slopes of Frith Hill, while many more packed the meadows around the gallows. Chennell ascended the steps without hesitation, but Chalcraft was seen to be trembling. Both were blindfolded and the rope was placed around their necks. Although they were given the opportunity, neither of them was prepared to confess to the murder. Chalcraft prayed and both repeated their assertion of innocence, but it was not enough to save them from their fate.

After they had been left hanging for an hour, their bodies were cut down, put into a wagon and driven through the streets of the town, back to the house where the murders had taken place. They were then carried into the kitchen, and left exposed to the gaze of thousands who formed a constant procession that day to come and view them. Afterwards they were given to Mr Parson and Mr Haines, two Godalming surgeons, for dissection.

3

‘YOU WILL KNOW WHO DID IT’

Walton Heath, 1834

John Richardson was the steward to a farmer and landowner, John Perkins of Bletchingley. One of his regular jobs was to attend the Epsom Cornmarket, which was established in 1833 and held every Wednesday. He often had to carry large sums of money with him as he went between Epsom and Bletchingley. He knew that in doing so he was taking a risk, and had a genuine fear of being robbed, possibly even murdered, on his way. Anyone who walked through those parts of the countryside, particularly Walton Heath, was liable to be attacked by highwaymen and footpads. In November 1833 Mr Hart, a Reigate solicitor, was held up by a gang of four armed men who had grabbed the head of his horse and threatened to shoot if he did not hand over his valuables. He knew that he was in no position but to accede to their demands. Ever since then, Richardson always ensured that he was accompanied on all his journeys, and he never travelled without carrying two loaded pistols. Whenever he drove, he had a pistol in one hand and his reins in the other, the second pistol being in his pocket.

On the morning of Wednesday 26 February 1834, he left Bletchingley in his gig for the regular Epsom market run. For once he did not have a companion in attendance, so he took the road with extra care. As he was riding across Walton Heath, he noticed two figures wearing smock-frocks. One was tall and thin, the other was much shorter. The wind was blowing strongly across the heath that day, pressing the men’s garments closely to their bodies. Under the smock of the taller man, Richardson thought he could make out the outline of a pistol. He whipped up his horse and hurried to report what he had seen to the toll-keeper at Tadworth, advising him to keep a careful eye out for both men as he suspected they were up to no good. On arrival in Epsom he went straight to the King’s Head for his market business, but he still could not forget the sight of both men. He mentioned it to Mr Butcher, an auctioneer and builder, and told other people he met during the day that ‘if you hear of my being robbed or murdered, you will know who did it.’

The Spread Eagle Tavern, Epsom.

During the day he was known to have received £23 3s from a Mr Stokes of Ewell. The money was made up of one £10 note and two £5 notes, three sovereigns and three shillings. After close of business he dined at the inn and had a glass of wine with a colleague at another Epsom public house, the Spread Eagle. He then returned to the King’s Head, his gig was prepared for him and he left for Bletchingley, both pistols at the ready as usual if needed.

By now it was 6 p.m. and darkness had fallen. He hurried along the road skirting the northern edge of the Downs, and entered a narrow lane at Buckle’s Gap leading to a deep hollow, Yew Tree Bottom. The road out of the hollow went up a short but steep hill, and here he got down to walk his horse to the top. There were steep banks on each side, which closed in the darkness around him as he made his way slowly up the hill towards Banstead. As he reached the brow of the hill, two figures came out from the side of the road. One seized the horse by its head, while the other demanded money. Richardson fired the pistol in his hand, but unfortunately missed his target. Before he could reach for the other in his pocket, one of his attackers returned fire and Richardson fell to the ground. The attackers took his money and one of the pistols, and ran off in the direction of a small wood, Rose Bushes, towards the Ewell to Banstead road.

John West, a carrier, had been a little way behind him. He jumped from his cart and gave chase, but before he could reach the brow of the hill, the men had disappeared. He made his way to the place from where he had heard the faint cry of alarm, and found the horse and gig at a standstill near the top of the hill. Richardson was lying on his back in the middle of the road, his head facing down the hill. When West reached him he was still just alive, but when he tried to raise the wounded man he sighed deeply and drew his final breath. The ball from the murderer’s pistol had grazed his left arm and passed through the body from one side to the other, missing the heart, but perforating the lungs. West placed the body in his cart and took him to the Surrey Yeoman at Banstead.

At the post-mortem, the ball was found lodged against the blade bone of the right shoulder. A magistrate, Mr Gosse, came to try and examine the scene later that evening, though there was little he could see by candlelight on such a dark night. They obtained good descriptions of the two men from the tollkeeper at Tadworth, as he had seen two men that morning and they matched the descriptions given by West.

The grim news was broken to Mrs Richardson and the children by the Revd Kendrick, rector of Bletchingley, and his wife, and the funeral was held on 2 March at Ashtead Church.

Several other people thought they had seen the culprits. Mr Smith, licensee of the Swan Inn, Leatherhead, said he thought the murderers were probably the same pair who had committed several highway robberies during the previous six months. He and his wife had been stopped at around 6.30 p.m. in June 1833 while travelling in a gig along Reigate Road, and the men who robbed him fitted the description given of Mr Richardson’s killers. When they were threatened, Mrs Smith had begged the men not to hurt them, whereupon the taller of the two assured them they would not, ‘but you must give us everything; let us have your watch first.’ Mr Smith handed them his gold watch, worth £40, and then the tall man demanded his money, which turned out to be seven sovereigns and 16s in silver. Other men came forward to say that they had been robbed on the same road by the men as well.

A pistol was discovered at the scene of the crime on the afternoon of 1 March, and a general meeting of the local magistrates was called that same evening. They decided to offer a reward of £100 for information leading to the arrest of the attackers. John Perkins, Richardson’s employer, added the same amount. The magistrates said afterwards that they had several clues to the identity of the men, and hoped to have them in custody within a day or two.

After making enquiries, on 3 March two police officers, Jefferson and Burridge, went to Sevenoaks, where they apprehended James Hill and John Reeves, arrested them on suspicion of murder, and took them for questioning by the magistrates. Hill denied that he had been in Surrey when Richardson was killed, while Reeves said he had not been near Epsom or Banstead. Both were remanded in custody for four days. It was suspected that they had been involved with a gang responsible for several robberies in Kent and Surrey. Another man, Charles Cottrell, was arrested in London. When he was taken into custody at a house in Bridport Street, Hoxton, he had marks of blood on a handkerchief found in his possession. He swore that the policemen would not take him alive, but rushed towards a table on which there were several knives, though they managed to stop him from doing any harm to himself. Some years earlier he had been implicated in the robbery of a Surrey clergyman’s house, when the servants were locked in a coal cellar.

A broadsheet headline published after the murder of John Richardson.

Nevertheless, there was insufficient evidence to charge any of these men with the murder of John Richardson. If they were the guilty men, they were fortunate in escaping their just deserts. If they were innocent, the killers had succeeded in making good their escape.

4

‘WHAT WAS DONE WAS NEVER INTENDED TO BE DONE’

Frimley, 1850

In 1850 the Revd George Edward Hollest, aged 56, had been vicar of Frimley for seventeen years. Frimley, part of the parish of Ash, was a small village consisting of about fifty houses. The Church of St Peter had been built in 1826, though Frimley did not become a separate parish until 1866. As a young man Hollest had studied at Cambridge University, and was one of the best players in the cricket team. In the village he was much loved and respected by the local community. He, his wife and two sons, aged 15 and 14, lived at the Parsonage, about 300 yards from the church, and employed a manservant and two maids. The Parsonage was a solid brick-built house standing in its own grounds at the western end of the village, with the nearest neighbours being about 100 yards away.