Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

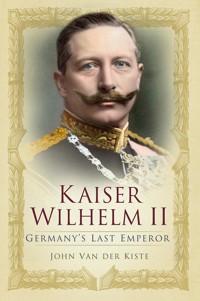

Drawing on a wide range of contemporary sources, this biography examines the complex personality of Germany's last emperor. Born in 1859, the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria, Prince Wilhelm was torn between two cultures - that of the Prussian Junker and that of the English liberal gentleman.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 563

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1999

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KAISER WILHELM II

Germany’s Last Emperor

Also by John Van der Kiste

Published by Sutton Publishing unless stated otherwise.

Frederick III: German Emperor 1888 (1981)

Queen Victoria’s Family: a Select Bibliography (Clover, 1982)

Dearest Affie: Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s Second Son, 1844–1900 (with Bee Jordaan) (1984, new edition 1995)

Queen Victoria’s Children (1986; large print ISIS, 1987)

Windsor and Habsburg: the British and Austrian Reigning Houses 1848–1922 (1987)

Edward VII’s Children (1989)

Princess Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia, 1876–1936 (1991)

George V’s Children (1991)

George III’s Children (1992)

Crowns in a Changing World: the British and European Monarchies 1901–36 (1993)

Kings of the Hellenes: the Greek Kings 1863–1974 (1994)

Childhood at Court 1819–1914 (1995)

Northern Crowns: the Kings of Modern Scandinavia (1996)

King George II and Queen Caroline (1997)

The Romanovs 1818–1959: Alexander II of Russia and his Family (1998)

The Georgian Princesses (2000)

Gilbert & Sulivan’s Christmas (2000)

KAISER WILHELM II

Germany’s Last Emperor

John Van der Kiste

First published in 1999

Paperback edition first published in 2001

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Van der Kiste, 1999, 2001, 2013

The right of John Van der Kiste to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9928 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Preface

1.

The Young Prince

2.

Marriage and Responsibility

3.

The Young Kaiser

4.

‘A Great Ruler and a Sensible Man?’

5.

The Quill and the Sword

6.

The Approaching Storm

7.

The Kaiser at War

8.

The Squire of Doorn

Genealogical Tables

Notes

Bibliography

Preface

Some twenty years ago I wrote my first full-length book, a biography of Kaiser Friedrich III. For several years I had been fascinated by the personality of this enigmatic, little-known, tragic ruler and his wife, Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter. I was equally intrigued by the personality of their eldest son Wilhelm, Friedrich’s successor, and just as much by the different, even contradictory, perceptions of him in almost every book I read. During his reign Wilhelm was spoken of indulgently as the man who wanted to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral. One of the shrewdest judges of character of the time, his uncle King Edward VII called him ‘the most brilliant failure in history’.

After Wilhelm’s abdication, the most hated man in Europe, he was later rehabilitated; alongside the demon Hitler, he seemed mild indeed. Nobody, Winston Churchill wrote in an admirably understanding essay in the 1930s, should judge the Kaiser’s career without asking the question, ‘What should I have done in his position?’ The future prime minister – who was to offer Wilhelm a safe haven in England a few years later – saw him as a solitary human figure raised by an accident of birth to be the ruler of a mighty nation, placed far above the status of ordinary mortals.1 When he died in June 1941, the historian G.P. Gooch paid tribute in the Contemporary Review to ‘an unsubstantial ghost’, whose patriotism was beyond challenge and intentions excellent, ‘but he never realised his unfitness to rule’. He called the Kaiser one of the vainest of men, but a good husband and to whose name no scandals clung; he also said Wilhelm was ‘entirely free from the virus of anti-Semitism’.2 This judgment, verging on the hagiographical, presented the image his surviving relatives wished to perpetuate. Broadly in line with Churchill’s verdict, it stood more or less unchallenged for about another four decades. In June 1974 the Monarchist League placed an announcement in the In Memoriam column of The Times: ‘His deposition made Nazism inevitable.’3

Was this the full truth about the Kaiser, the ruler who was partly English by birth, sometimes ardently pro-English in his sympathies, yet a personification of Prussian militarism at its worst? Was he just the handicapped child who became an expert shot and horseman, the grandson who adored and revered Queen Victoria though he occasionally made fun of her, the virtuous, God-fearing, faithful husband and devoted father? Or was he the cruel and disloyal son who alternately mocked his mother and accused her of treason; the bisexual philanderer who indulged in illicit liaisons behind his doting wife’s back and terrified his sons when he was at home; the warlord who spoke of cutting down his enemies without mercy in speech after speech while seen by his entourage and family as a weak and cowardly figure behind the bombast and bluster?

As a subject for biography he has been well, even indulgently, served by the sympathetic scholarship of Michael Balfour in The Kaiser and his Times (1964). Balfour saw in him a sovereign who claimed to be a leader while ‘in fact he followed others and allowed himself to be moulded by his environment instead of impressing his personality upon it’. Instead of blaming him for the catastrophe of ‘the Kaiser’s war’, he asks, ‘should not one blame instead the system which could assign so onerous a post to someone who had so little chance of filling it with credit?’4 Tyler Whittle’s similarly impartial The Last Kaiser (1977) was hailed by some authorities in Germany, alongside J. Daniel Chamier’s Fabulous Monster (1934), as evidence that only English writers had the necessary imagination and freedom from prejudice to recognize him as the ‘tragic hero’ that he was.5 The Kaiser was lucky to have such faithful guardians of his reputation, but since then a darker picture has emerged.

By this time the ‘Fischer controversy’ of 1961 had broken the patriotic self-censorship policy by accepting the significance of the Kriegsrat of December 1912 and thus established beyond reasonable doubt that Germany’s aims in the First World War had been broadly similar to those pursued under Hitler, and that she bore a major share of responsibility for causing that earlier conflict. It followed that the central figure at the apex of Wilhelmine Germany, while not the autocrat he fondly imagined himself to be, was himself therefore somewhat responsible. The pendulum of condemnation that pointed the finger at him for being at least partly to blame for starting ‘the Kaiser’s war’, which had moved away from him in a period of impartial reflection, was swinging back. By the 1970s the tougher, more penetrating scholarship of John Röhl, whose recent discovery of other papers, notably the original diaries of three of the Kaiser’s confidantes, helped to pave the way for a more honest if less kindly portrait of the Kaiser. Count Robert von Zedlitz-Trütschler, the Kaiser’s court marshal from 1900 to 1912, had published selections from his diary as long ago as 1923. Though the full version has never been discovered, these edited extracts were so damning that one commentator referred to them as the vengeful courtier’s ‘spitoon’, thus leading one to wonder what had been withheld. The Kaiser’s head of the naval cabinet, Admiral Georg von Müller, left journals published posthumously in two volumes in 1959 and 1965, but he had doctored them carefully himself in the 1920s and the editor had also prudently removed certain passages from the final edition. Finally Captain Sigurd von Ilsemann, the Kaiser’s adjutant in exile, left two similar volumes published in German a little later, from which several damning paragraphs were omitted at the request of the Hohenzollern family immediately prior to publication. ‘It always makes me quite ill to hear the Kaiser speak in this manner. What would the judgment of history be if the public were to learn of such talk?’6 read one such entry, referring to an anti-Semitic tirade, for July 1927.

The turning point came in 1977 when Professor Röhl and Nicolaus Sombart jointly directed a seminar at the University of Freiburg on ‘Kaiser Wilhelm II as a Cultural Phenomenon’. Two years later Röhl and Sombart and a group of other historians gathered at Corfu to debate and present papers on the Kaiser, his influence on Germany’s policies, and his relationship to contemporary German society. No biographer of the Kaiser can fail to acknowledge the great debt to their pioneering studies which resulted from these. As well as Röhl’s researches, mention must also be made of the magisterial two-volume work by Lamar Cecil of the character whom he calls ‘an exceedingly foolish man, so that to explain – and sometimes merely to relate – what he did or said reduces a biographer to the greatest perplexity,’7 and of Hannah Pakula’s biography of the Empress Frederick, the most detailed and penetrating account yet of this much misunderstood, tragic figure. Significantly, the new primary material in these books, while adding much to our understanding of the Kaiser, reinforces the impression that Balfour’s and Whittle’s assessments erred on the side of generosity.

Strangely, some contemporary German historians took it upon themselves to argue that ‘everything worth knowing’ about the Kaiser and his Court had been discovered long ago, that a preoccupation with such matters was dangerously retrogressive and ‘personalistic’, and to emphasize the monarchical aspects of Wilhelmine political culture was to be ‘historicist’ and to weaken the relevance of historical study to an understanding of contemporary politics.8 Such arguments may be the natural corollary of Marxist historians who dispute the effect of monarchs on the events and society of their time, but not of those who would rather accept Thomas Carlyle’s verdicts that ‘history is the essence of innumerable biographies’, and that ‘the history of the world is but the biography of great men’ (and also men whose greatness is disputed).

By any standards the contradictory, baffling, larger-than-life personality of Kaiser Wilhelm II is one that cries out for continued study. The eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort was one in a succession of modern German figures who sought to raise Prussia to preeminence in, if not total domination of, Europe, in a line that began with Bismarck and could be followed through Wilhelm II to Hitler and Köhl. On the threshold of the millennium, one would do well to remember the former Kaiser’s words in a letter to his last surviving sister (3 November 1940), looking forward to ‘the U.S. of Europe under German leadership, a united European Continent’, and compare them with the writings (May 1940) of Herr Clodius, Deputy Director of the German Foreign Ministry, of a vision for a new Europe which he called ‘a Greater Germany’, and those of German Chancellor Helmut Köhl (September 1995) in a speech to the Council of Europe, calling for ‘the political union of Europe’ and affirming in his view that ‘if there is no monetary union then there cannot be political union, and vice versa’.9

With regard to the use of English and German names, I have followed the modern style of reader recognition rather than consistency. Therefore the subject of this book is Wilhelm rather than William, and his father Friedrich rather than Frederick, while his mother is referred to by her English rather than German names. To avoid confusion between the German and Austrian sovereigns, Wilhelm and his predecessors are ‘Kaiser’ throughout, while Franz Josef and his successor Karl are ‘Emperor’.

I wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen to publish certain material of which she owns the copyright; and the kind permission of Ian Shapiro, at Argyll Etkin Ltd, and of Dale Headington, at Regal Reader, for the use of previously unpublished manuscript material. My friends Karen Roth, Shirley Stapley, Theo Aronson, Roman Golicz, Robert Hopkins and Robin Piguet have been unstinting in their advice, encouragement and supply or loan of various materials for research. The staff of Kensington & Chelsea Borough Public Library have again been kind enough to allow me the run of their incomparable reserve biography collection. Last but not least, thanks are due to my mother, Kate Van der Kiste, for reading through the draft manuscript and recommending countless improvements in both content and clarity, and to my editors, Jaqueline Mitchell and Alison Flowers, for helping to see the finished work through to publication.

CHAPTER ONE

The Young Prince

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia was born on 18 October 1831 in the Neue Palais, Potsdam. He was the first child of Wilhelm, second in line to the throne of Prussia after his father, King Friedrich Wilhelm III, and eldest brother, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, and Augusta, daughter of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar.

Wilhelm and Augusta had been married in June 1829. For some time he had been in love with Princess Elise Radziwill, a member of the Polish aristocracy deemed of insufficiently noble birth to marry a Hohenzollern of Prussia. Having declared solemnly that he would never give his heart to another, the Prince obediently proposed to Augusta, who accepted him with a dutiful lack of enthusiasm that matched his own. He was a Prussian soldier through and through, while she had been brought up at the liberal court of Weimar, devoted to music, literature and art. Those who knew her well predicted, all too accurately, that her life in philistine Prussia would not be happy.

Husband and wife had little in common, and by the time of their son’s birth they had developed such a mutual aversion that they were leading almost separate lives. It was impossible for them to stay in the same room for long without quarrelling. Though the heir apparent, Wilhelm’s elder brother and his wife Elizabeth, had not managed to produce a child, Wilhelm and Augusta showed no undue concern with ensuring the succession. Seven years later, in December 1838, a daughter named Louise was born, and Augusta declared that she had fulfilled her marital duty. In June 1840 King Friedrich Wilhelm III died after a reign of forty-three years. His eldest son succeeded him, taking the title of Friedrich Wilhelm IV. As heir apparent, Wilhelm assumed the title of Prince of Prussia and his eight-year-old son became heir presumptive.

Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, or ‘Fritz’, as the family called him throughout his life, was a lonely child. His unimaginative father only took a perfunctory interest in him, adamant that he should grow up to be a good soldier but little more. A conventional upbringing was supervised by nurses and governesses until the age of seven, when he was entrusted to a military governor and tutor. Always closer to his mother, he took after her in many ways, particularly in his love of reading and later a liberal outlook on the issues of the day. When he was eighteen he astonished the reactionary General Leopold von Gerlach, who had told him how he envied the young man his youth ‘for he would no doubt survive the end of the absurd Constitutionalism. He was of opinion that a representation of the people would become a necessity, and I endeavoured to make it clear to him that Constitutionalism did not necessarily follow upon the absence of Absolutism.’1

In August 1845 Queen Victoria of England and Prince Albert visited the Prussian royal family at Aachen and were guests of honour at a special banquet. Thirteen months later Augusta was invited to stay with them for a week at Windsor. Acquaintance soon ripened into mutual friendship, and with it Albert’s vision, inspired largely by his Uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, and mentor Baron Christian von Stockmar, of a Prussia allied to Britain, at the head of a united, constitutional Germany. Who better to reign over this Greater Germany than their friend’s son Friedrich, as King or even Kaiser, and his consort – their beloved eldest child ‘Vicky’, Victoria, Princess Royal?

In May 1851 Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition, a tribute to the industrial and artistic skills of peacetime Britain and her empire, opened in London. Taking their pride of place as guests were the Prince of Prussia, who had come with great reluctance, his wife and son. The ten-year-old Princess Royal was something of a child prodigy. Almost as soon as she could read she was fluent in French and German as well as English, and she shared her father’s intellectual, artistic and political interests. She acted as a very knowledgeable guide as she showed Friedrich around the exhibits. By the time he and his parents were back in Berlin, he was as firm in his Anglophile inclinations as his mother. While he could hardly have been in love with the vivacious youngster who had escorted him around with such enthusiasm, he must have realized that a tentative future was being planned for him by the elder generation.

In September 1855 Friedrich was invited to Britain again, this time without his parents, to stay with Queen Victoria and the family at Balmoral, their Scottish Highland home. He had parental permission to propose to the princess, now a very forward fourteen year old, and probably did not dare to return home without having done so. On 29 September they all went out riding with the young couple lagging behind. Friedrich picked a sprig of white heather as an emblem of good luck, telling Victoria nervously as he presented it to her that he hoped she would come to stay with him in Prussia – always. On the day after his departure, Albert wrote to tell Baron Stockmar of the week’s events, adding that the young people were ‘ardently in love with one another, and the purity, innocence, and unselfishness of the young man have been on his part equally touching’.2

As the bride-to-be was still so young, there was no question of an immediate official announcement of the engagement, though disapproving tongues wagged in Berlin and the news leaked out within a few days. In a leading article (3 October) The Times attacked the engagement as ‘unfortunate’, calling Prussia a ‘wretched German state’, and the Hohenzollerns ‘a paltry German dynasty’. When the betrothal was announced to the courts of Europe in April 1856 a rising young conservative politician, Otto Bismarck, then Prussian representative at the German Bundestag in Frankfurt, summed up the prevailing view in Berlin in a letter to General Gerlach: ‘If the Princess can leave the Englishwoman at home and become a Prussian, then she may be a blessing to the country. If our future Queen on the Prussian throne remains the least bit English, then I see our Court surrounded by English influence. . . . What will it be like when the first lady in the land is an Englishwoman?’3

The wedding was scheduled to take place in January 1858, two months after the bride’s seventeenth birthday. In Berlin the Court had taken it for granted that their future King would lead his consort up the aisle there. Queen Victoria had decided otherwise, as she informed Lord Clarendon, her Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (25 October 1857): ‘Whatever may be the usual practice of Prussian princes, it is not every day that one marries the eldest daughter of the Queen of England. The question therefore must be considered as settled and closed.’4 Three months later to the day, Monday 25 January 1858, families and guests gathered in the chapel at St James’s Palace where Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, just promoted to the rank of major-general of the Prussian First Infantry Regiment of Guards, led his trembling bride, radiant in a dress of white silk trimmed with Honiton lace, to the altar. After a two-day honeymoon at Windsor Castle for the couple, ‘two young innocent things – almost too shy to talk to one another’5 in the bride’s words, they returned to Buckingham Palace to join the family again, and then to Gravesend for their departure on the yacht Victoria and Albert to Prussia.

They entered Berlin on 8 February, a bitterly cold day. Wearing a low-cut dress without any wrap or coat for extra warmth, the quietly shivering Princess immediately disarmed Queen Elizabeth of Prussia, who had had no enthusiasm for her nephew’s ‘English marriage’. She asked the girl if she was not frozen. ‘Completely, except for my heart, which is warm,’ was the tactful answer. They settled in the Berlin Schloss, a shock for a young woman so used to English standards of comfort and cleanliness. There was a constant stench of bad drains, no bathrooms or running water, the beds were infested with bugs and long-disused rooms were knee-deep with dead bats. The Princess’s in-laws were an unwelcoming, unprepossessing crowd, from the prematurely senile King, the embittered Anglophobe Queen Elizabeth, the ever-bickering regent and his wife, to the loud-mouthed, heel-clicking princes who unashamedly regarded their wives as second-class citizens, brood mares and nothing more.

By early summer the Princess was expecting a child. Neither of the prospective grandmothers seemed to be pleased, Queen Victoria rather ungraciously calling it ‘horrid news’ which made her ‘feel certain almost it will all end in nothing’.6 The Princess was unwell throughout autumn and winter, but her physician Dr Wegner refused to believe there were grounds for concern, as did Queen Victoria’s own physician, Dr James Clark, when he was sent to examine her. He insisted blandly that everything would revert to normal once the baby was born. Only her experienced midwife, Mrs Innocent, had any idea of the horrors in store. Arriving in Berlin soon after Christmas 1858, she took one look at the expectant princess and feared that they were ‘in for trouble.’7

Precisely what happened at Unter den Linden at the childbed of Princess Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia will probably never be known. Amid all the conflicting accounts of events, only one thing can be said with certainty – that the doctors and physicians were retrospectively involved to a considerable degree in covering up a mismanaged birth which nearly cost the lives of mother and child. The assertion that Queen Victoria distrusted most of the German doctors and sent Dr Eduard Martin, a German accoucheur who had however proved his ability by attending her own last pregnancy in 1857, is less likely than the theory that Prince Wilhelm took Baron Stockmar’s advice and engaged the services of Dr Martin, at that time chief of obstetrics at the University of Berlin, as the man best qualified to assist. There was evidently some professional jealousy between both men, and Wegner, more courtier than physician, hesitated to jeopardize the sensibilities of his royal patient by conducting the necessary examination8 – even at the risk of letting nature take its course by allowing her and her child to die. Mortality in childbirth was not uncommon, and it was unlikely that his professional reputation in Berlin would have been damaged if this had been the outcome.*

When the Princess’s labour began shortly before midnight on 26 January, Dr Wegner, Dr Clark, at least one other German doctor (though no names have been mentioned in subsequent reports and accounts), the midwife, Countess Blücher and Countess Perponcher, a lady of the bedchamber, were on hand, and the father-to-be was also present. Countess Blücher, an Englishwoman married to a German, was a confidante of Queen Victoria, Princess Augusta, and one of the few women in Berlin whom Princess Friedrich Wilhelm could trust implicitly. It was evidently thanks to the Countess that the mother-to-be had a badly needed crash course in the ‘intimacies’ of childbirth that Queen Victoria, with her disgust for anatomical details, had never been able to bring herself to impart to her daughter. Wegner scribbled a note summoning Dr Martin at once, but it was given to a servant who posted it instead of delivering it by hand – whether out of carelessness or for more sinister reasons was never established.9 As a result it did not reach Dr Martin’s residence until 8 a.m. the next day, after he had already left on his rounds. Two hours later he was getting into his carriage for the university lecture hall when he received the note with the rest of his morning mail. Simultaneously another footman appeared, summoning him to the palace at once.

To his horror Dr Martin found Dr Wegner and his German colleague or colleagues in a corner of the room while the distraught Prince Friedrich Wilhelm held his semi-conscious wife in his arms, having put a handkerchief into her mouth several times to prevent her from grinding her teeth and biting herself.10 One of the doctors told him resignedly, in English, that it was no use, ‘the Princess and her child are dying’.11 At the sound of voices the Princess opened her eyes, and from her expression Dr Martin was convinced that she had understood. It was thanks to his grim determination that the mother lived, as did the son to whom she gave birth minutes later. Statistically the odds had been heavily against him. That same year, 98 per cent of German babies born in the breech position, as this one was, were stillborn.12

‘In truth I could not go through such another’,13 Dr Clark wrote to Queen Victoria later that week. The young mother wrote to Queen Victoria that Dr Wegner had showed ‘a great deal of tact, discretion, feeling during the whole time . . . but I do not know what I should have done without Sir James’, while as for Dr Martin, to whom she had initially taken a violent dislike, he was ‘an excellent man & I feel the greatest confidence in his skill’, but she could never absolve him completely from blame for the ‘bungling way’ in which she was treated.14 Wegner claimed the credit for bringing her and her son through the whole business, which he hardly deserved. Exhausted by her ordeal, she was confined to bed for a month. By the time she had recovered, it was too long after the event for her to realize who had genuinely saved her life. Some sixty years later, a war-weary continent might have had good reason to rue the doctors’ devotion to duty, at least where their part in saving the baby was concerned.

At 3 p.m. 101 salutes were fired to announce the arrival of a new prince, third in line to the throne of Prussia. Newspaper editors in their offices had been alerted to the potential tragedy nearby by a messenger sent by the despairing doctors. Only as the echoes died away did they realize that Her Royal Highness Princess Friedrich Wilhelm’s obituary could be put on hold. Meanwhile, crowds stood around in the falling snow, patiently awaiting the news. In his excitement the war veteran Field-Marshal Wrangel strode out on to the palace balcony to tell them optimistically that the infant was ‘as sturdy a little recruit as heart could wish to see!’.15

Dr Martin’s grim report, written a fortnight later, was closer to the truth when he called the baby ‘seemingly dead to a high degree’.16 All the doctors concentrated on trying to save the mother. Her child was handed to a German midwife, Fraulein Stahl, who repeatedly smacked the tiny bundle until his lungs began to function and he started crying. Wrapped carefully in his layette, he was then presented to his paternal grandparents and a circle of courtiers who admired him and congratulated the shattered father on having ensured the succession for another generation.

Three or four days after the birth Mrs Innocent drew Dr Martin’s attention to the baby’s left arm, hanging lifelessly from the shoulder socket. The father was told at once. When he asked the German doctors, they reassured him that the damage was only temporary paralysis which would improve with a little gentle massage at first, followed by exercises at a later stage.

What was the effect of the child’s disability on his subsequent character? In his own memoirs, written and published sixty-seven years hence, he noted with admirable sang-froid that his arm ‘had received an injury unnoticed at the time, which proved permanent and impeded its free movement’.17 Even when he was an adult it remained about 6 in shorter than the right. Adorned with heavy rings, the hand was perfectly formed and looked healthy apart from an ugly brown mole, but it was too weak to grip or hold anything heavier than a piece of paper. It would just go into his coat pocket, where he could keep it out of sight. Throughout his life few photographs showed his left arm clearly, let alone the hand; from an early age, the art of concealing it from the camera lens became second nature to him. At meals he could not manage an ordinary knife and fork, but his bodyguard always carried a special combined one, while the person sitting next to him discreetly cut up his food. As if to compensate, his right hand had an iron grip, something he would often exploit as an adult when greeting people for the first time with a vice-like handshake, sadistically turning the rings on his fingers inwards first so as to add to the other person’s discomfort. If these men or women were English, he laughed heartily at their winces as he made jibes about ‘the mailed fist’.

The injuries were not confined to an undeveloped hand. His neck had also been damaged at birth – as the arm and hand muscles and nerves were all torn from the vertebral column in the neck during the final stages of delivery, his head was tilted abnormally to the left, and the cervical nerve plexus was subsequently damaged. The hearing labyrinth of the left ear was defective, resulting in partial deafness from childhood and lifelong problems with balance, probably as a result of damage to part of the brain closest to the inner ear. Throughout adolescence and early manhood he suffered from alarming growths and inflammations of the inner ear, and at the age of forty-seven he underwent a major operation which left him deaf in the right ear as well.18

A theory that lack of oxygen in the first few minutes of life caused some degree of irreversible brain damage can neither be proved nor ruled out. In the case of a child whose closest antecedents numbered at least two cases of severe mental instability, it was a worrying possibility. Perhaps one can attach undue importance to the fact that the boy’s great-great grandfathers, Tsar Paul of Russia on his father’s side, and King George III of England on that of his mother, had been considered insane in their latter years, as well as the fact that the then King of Prussia, the boy’s childless great-uncle, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, was likewise so mentally enfeebled by this time that he had little perception of events around him. Nevertheless the theory of brain damage, or insanity, if not a disquieting combination of both, cannot be disregarded. Not for many years was King George III’s ‘madness’ more correctly ascribed to a combination of senile dementia and porphyria, an inherited constitutional metabolic disorder which, recent evidence suggests, may have been passed down to the Princess, and in turn to her eldest daughter and possibly this eldest son as well. When Prince Friedrich Wilhelm and his father were told of the baby’s disability, the unsympathetic grandfather remarked coldly that he was not sure whether congratulations on the birth of a defective Prince were in order.19

‘What epithet history will attach to his name is in the lap of the gods,’ the Prince Consort wrote rather ponderously to his daughter in March; ‘not Rufus if your wishes come true, not The Conqueror, perhaps “the Great”? There is none with this designation . . . we have had “the Silent”, but that should not mean that your son will be a chatterbox.’20 As an adult Wilhelm would have surely felt ‘the Great’ was an appropriate designation, but as Kaiser of Europe’s most aggressive military power he would never be able to lay claim to that of ‘the Conqueror’, and rarely would a monarch be less deserving of ‘the Silent’. ‘Chatterbox’ proved more prophetic.

With the resilience of youth, the Princess put a brave face on her son’s deformity, emphasizing his positive qualities in a letter to Queen Victoria (28 February); ‘Your grandson is exceedingly lively and when awake will not be satisfied unless kept dancing about continually. He scratches his face and tears his caps and makes every sort of extraordinary little noise, I am so thankful, so happy, he is a boy. I longed for one more than I can describe, my whole heart was set upon a boy and therefore I did not expect one.’21 Some weeks later she ruefully mentioned to her mother what she thought was the cause of the child’s disabilities – a severe fall on a slippery parquet floor in the Schloss the previous September, when she caught her foot in a chair, ‘to which I attribute all my misfortunes and baby’s false position’.22

Christenings of royal Prussian children generally took place when the baby was three weeks old, but in this case it was delayed because of the mother’s delicate state of health. Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Victor Albert, the last two names in honour of his grandparents in England, was baptized on 5 March. To their disappointment they were unable to attend, and the Queen was represented by Lord Raglan, the Crimean war commander. Proud as she was of her son, the Princess felt anguish ‘to see him half covered up to hide his arm which dangled without use or power by his side’.23 For a time she was much preoccupied with the best course of action for his arm. His English nurse Mrs Hobbs rubbed massage oil on it faithfully, telling the sceptical mother that she was sure it was working, although neither really believed it. Another British doctor, Sir Benjamin Brodie, was asked by Queen Victoria to examine the child and discuss the matter with Sir James Clark. He recommended that the right arm should be tied up occasionally in order to force the Prince to use his left, but managed to convince everyone except the Princess that it was gradually improving and would eventually reach normal length. The suggestion, she pointed out patiently to Queen Victoria, was nothing new, as the arm had been tied down to his side and leg for an hour a day. He did not mind it in the least, but lay on his back on the floor or the sofa kicking his legs in the air, ‘laughing and crowing to the ceiling as happy and contented as possible’. To her he seemed unaware that he had another arm as there was evidently so little feeling in it.24

The Princess doted on babies, and within a few days of his birth she had started breast-feeding him, to the revulsion of her mother-in-law. Knowing Queen Victoria’s views on the subject were at one with hers, she wrote to the Queen asking for her approval in putting an end to ‘this odious habit’. Much to the young mother’s disappointment her baby was promptly handed over to a wet nurse, whose milk irritated his bowels and caused regular stomach upsets. Some years later Augusta, by then Empress, told her grandson – by this time only too eager to hear anything against his mother – the cruel lie that she could not face feeding him herself because she found his injured arm repugnant.25 The parents adored their firstborn child, and Prince Friedrich Wilhelm carried him proudly around the palace, showing him off to anybody who was around. To an aunt he wrote that ‘in his clear blue eyes we can already see signs of sparkling intelligence’.26 The Princess wrote to her mother that he was ‘really a dear little child, he is so intelligent and lively & cries so little, but as he is so forward, great care must be taken not to excite him’.27

Not until September 1860, by which time he was twenty months old, did Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort have an opportunity to see him. Now he was not alone in the nursery, for in July after an easy labour Vicky had given birth to a daughter, whom they named Charlotte.

On 2 January 1861 the prematurely senile King Friedrich Wilhelm IV died, and the regent became King Wilhelm I. Aged sixty-three, he was sure that his reign would not last long. That August Wilhelm, now second in succession to the throne, made his first trip abroad when he and his parents spent a few weeks at Osborne on the Isle of Wight. This, he would later write, was the scene of his earliest distinct recollections, especially the Prince Consort dandling him in a table napkin.28 As the only one of Queen Victoria’s grandsons whom ‘Grandpapa Albert’ ever saw, he would always have a special place in the indulgent, ever-forgiving Queen’s affections. Within four months the tired, careworn Prince Consort was dead. His grief-stricken eldest daughter had only just recovered from a serious attack of influenza and she was unable to join her widowed mother. Her husband left for England immediately and was one of the chief mourners at the funeral.

Wilhelm’s next journey to England was in March 1863 for the wedding of his ‘uncle Bertie’, Prince of Wales, to Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Clad in Highland costume, Wilhelm – now ‘Willy’ en famille – cheerfully made an exhibition of himself. On his way to St George’s Chapel, Windsor, he threw his Aunt Beatrice’s muff out of the carriage window. Beatrice was only five years old at the time, and in no position to exercise any authority over him. Queen Victoria’s youngest child, she was and always remained her mother’s ‘Baby’, a name her nephew soon picked up. When she told him petulantly that he must address her as aunt, he snapped back, ‘Aunt Baby, then!’ Bored during the long marriage service, while most of his relations were shedding emotional tears, he pulled the dirk from his stocking and threw it noisily across the chapel floor. When his young uncles Arthur and Leopold remonstrated with him, he bit them in the legs.

Such high-spirited mischief was seen again eight months later, when the family were back at Windsor and the artist William Powell Frith was engaged on an official group portrait of the wedding. Willy was fascinated to watch the picture taking shape, but could not resist teasing the painter. ‘Mr Fiff, you are a nice man, but your whiskers ——’. His Aunt Helena came and put a hand over his mouth, but he struggled free and repeated himself more loudly than ever. She stopped him again, blushing but unable to suppress her laughter as she led him to another corner of the studio and lectured him on good manners. As he could hardly order ‘the royal imp’ out, to keep him quiet Frith let him paint his own daubs on one very small part of the vast canvas. All was well until his nurse came in, saw his face and cried out in horror. He had been wiping his brushes on it, richly decorating himself with uneven streaks of bright colour. Assuring her that he could fix it at once, Frith grabbed the child firmly with one hand and rubbed turpentine into his face with the other. Some got into a scratch on his skin, and he screamed as he struck the artist as hard as his good fist would allow, before hiding under the table and howled until he was exhausted. Thereafter he proved such an uncooperative sitter for his appearance in the picture that the artist never captured more than a vague likeness.29

Little did Prince Wilhelm know that his nursery years were unsettling times for his parents. They had both been shocked, and his mother temporarily shattered, by the unexpected death of the Prince Consort in December 1861 at a time when they sorely needed his advice and moral support. King Wilhelm I intended to reform the Prussian army, and his Landtag, the Prussian parliament, would not accept his proposals for strengthening the regular forces and weakening the reserve Landwehr, or land army. Asserting his prerogative, the King dismissed his ministers and dissolved the Landtag. New elections strengthened liberal representation at the strength of the conservatives, and the new assembly refused to vote additional funds for the King’s reforms. By the summer of 1862 the matter had reached constitutional deadlock, with neither sovereign nor ministers and elected representatives prepared to compromise. In September the King told Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm with regret that he was going to abdicate; God and his conscience, he solemnly averred, would not allow him to do anything else. Totally unprepared, not to say deceived by the actor in his father, the Prince begged him to reconsider. In fact the offer was sheer bluff, for the King’s trusted admirer and confidant, General Albrecht von Roon, had telegraphed Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian ambassador in Paris, recalling him to Berlin immediately to head a new government, as the only man ruthless enough to take on the Landtag, defy the constitution and carry the King’s reforms through. Bismarck duly obeyed the call and was appointed minister-president of Prussia.

Neither the Crown Prince nor Princess had any illusions about the man who was just beginning nearly thirty years of rule over Prussia. The Crown Prince’s distrust had been awakened by the minister’s own report of a meeting in London with the Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and his Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord John Russell, and Bismarck’s statement that he found the English constitution alien to his philosophy as it allowed for ‘great and permanent encroachments on the prerogatives of the Crown, especially in military matters’. This despatch, he told his wife, ‘foretells what might be in store for us if that man were sooner or later to control the destinies of Prussia’.30 To the Crown Princess he was ‘a most unprincipled and unrespectable character – a brouillon and an adventurer’.31 Bismarck’s statement in a speech to the chamber of deputies made his philosophy clear: ‘Germany does not look to Prussia’s liberalism, but to Prussia’s might. The great questions of the times will not be solved by speeches and majority decisions, but by iron and blood.’32

By the time they came to England for the wedding of the Prince of Wales in March 1863, they were seriously considering asking Queen Victoria if she could persuade King Wilhelm to allow them to live for half of every year in England.33 Returning to Prussia, they realized that such a gesture would look like running away. They struck a blow against the forces of reaction when the Crown Prince made a speech at Danzig in June 1863 publicly disassociating himself from a measure announced by Bismarck and endorsed by the King curtailing the freedom of the Prussian press. The King was beside himself with rage, and when the Crown Prince refused to apologize or retract his statement he threatened to have his son imprisoned in a fortress, but Bismarck knew that martyrdom would be counter-productive. ‘Deal gently with the young man Absalom’ he advised, choosing to give the heir a severe reprimand and ordering him not to make any similar pronouncements in future. The matter was dropped – but neither forgiven nor forgotten.

Wilhelm was aged four at the time of the ‘Danzig incident’. Though much too young to know what his parents were going through, the tense atmosphere doubtless communicated itself to him. Within a few years he would be taking sides himself in what almost amounted to civil war within the family, and it would not be on the same side as that of his parents.

At the time he had other problems on his mind, none greater than that of the machine supposed to rectify the damage done to him at birth. First used in April 1863 when he was aged four, it comprised a belt round the waist to which was affixed an iron bar passing up the back, with an object looking like a horse bridle attached. Into this the head was strapped and turned as required, the iron being moved by a screw. When the head was held firmly in the leather straps it was forced to turn to the left in order to stretch muscles on the right side of the neck, and prevent his head from being drawn down to the right. This was to be worn for an hour a day, and if there was no discernible improvement within a month or so, the doctors would recommend an operation which involved cutting some of the sinews of the neck. Dr Wegner assured the Crown Princess that it did not matter if her son walked around while wearing the machine, thinking there was no need to keep it secret, and the man who made the instrument was sure to talk about it throughout Berlin. Horrified at such insensitivity, the Crown Prince and Princess told him firmly that they would forbid anybody else from seeing him wearing it.34

In the end the neck operation was not carried out, probably because it was such a risky procedure and the doctors thought twice about experimenting on such an illustrious patient. To risk turning their slightly handicapped future King into a complete invalid or even worse was something to be avoided at all costs. Even so, it is doubtful whether the machine had any positive effect, other than making the boy more determined than ever to overcome his disability. The very sight of it caused tantrums and made him difficult to control. More useful were the exercises prescribed to make him hold himself upright and try to use his left arm more. A sergeant would arrive every morning to take charge of him, and if he did not feel in the mood to do his exercises he would announce that he was about to say his prayers or recite poetry instead.35

Despite this, Wilhelm and the other children had relatively happy childhoods. By the time he reached his fifth birthday he and his sister Charlotte, or ‘Ditta’, after his attempts to call her ‘sister’, had a brother Henry, born in August 1862. During the next ten years the Crown Princess would have five more children, of whom three survived to maturity. By the standards of the day it was not perhaps a large family, but that she should have had seven more after being extremely fortunate to come through her first experience of childbirth was little short of remarkable. In an age when the dictum that ‘children should be seen and not heard’ ruled, and that they should spend little time with their parents, the Prussian royal children were fortunate in belonging to such a close-knit family. Among Wilhelm’s happiest memories of these early years was being allowed to sit with his mother while she painted in her studio. A gifted artist, she was equally adept at sketching, and painting in oils and watercolours, and she liked him to read aloud as she worked on her art or embroidery.

The Crown Prince saw much more of his children than he had seen of his own father at a similar age. Though he was a war hero to his sons and daughters after he returned from fighting in the short and victorious Prusso-Danish War of 1864 – a war which brought him into collision with his brother-in-law the Prince of Wales, furious at Prussia’s cavalier treatment of his wife’s country – his military duties, parades, manoeuvres and inspections were not so intensive that he was denied time to be with his family while they were growing up. Part of the reason was that Bismarck and the King deprived him of responsibility as a result of his speech at Danzig. Therefore, the Crown Prince had every opportunity to pass on his great interest in ancient and medieval history and archaeology to his sons. Wilhelm was spellbound by a massive volume, German Treasures of the Holy Roman Empire, so vast that his father had to place it on the floor as he turned its pages, explaining the illustrations to his son, and conveying his hopes of restoring the German Empire which had existed in medieval Europe.

At other times he would take the children on visits to relatives, to museums and galleries, or on long walks in the countryside. He taught them to swim, row and sail on the River Havel, and when they were older he took them hunting. That Wilhelm became a good swimmer and proficient at rowing despite his weak arm says much for his determination. He could be forgiven for showing signs of pride, something Queen Victoria frequently counselled against, warning the Crown Princess to ‘bring him up simply, plainly, not with that terrible Prussian pride and ambition which grieved dear Papa so much and which he always said would stand in the way of Prussia taking that lead in Germany which he ever wished her to do’.36

In January 1866, at the age of seven, Wilhelm left the nursery and moved into the schoolroom. Captain von Schrotter of the guards artillery, later a military attaché in London, was appointed his governor. A sergeant was engaged to teach him to play the drum, and a schoolmaster from Potsdam to teach him reading and writing. Six months later Georg Hinzpeter was chosen as his civil tutor. Nobody had a greater influence on the boy’s character than this severe bachelor of thirty-eight with a doctor’s degree in philosophy and classical philology, and not always for the good. His educational system, comprising twelve hours a day of study and physical exercise, was ‘based exclusively on a stern sense of duty and the idea of service; the character was to be fortified by perpetual “renunciation”, the life of the prince to be moulded on lines of “old Prussian simplicity” – the ideal being the harsh discipline of the Spartans’.37 The Crown Prince and Princess were so impressed with him that Henry was also committed to his charge two years later.

It was part of Hinzpeter’s policy never to give the boys any praise, approval or encouragement. For breakfast they ate dry bread, and at tea they were only allowed bread and butter. When their cousins were invited to join them for tea, they had to be perfect hosts and offer them appetising-looking cakes without eating any themselves. As Wilhelm recognized, in retrospect if not at the time, this regime was easily explained: ‘The impossible was expected of the pupil in order to force him to the nearest degree of perfection. Naturally, the impossible goal could never be achieved; logically, therefore, the praise which registers approval was also excluded.’38 Hinzpeter did his work well, but with brutal efficiency. Humourless, with no understanding of a child’s nature, he incurred the distrust of Ernst von Stockmar, son of the Prince of Wales’s former tutor and former secretary to the Crown Prince and Princess. Fearful of being accused of interference if he spoke his mind too strongly, Stockmar had had his doubts about Hinzpeter on first sight and was tempted to warn them prior to appointing him that ‘he wants heart and is a hard Spartan idealist’.39

Hinzpeter’s supervision extended beyond the schoolroom. Every Wednesday and Saturday they visited museums, galleries, factories, foundries, workshops, farms or mines, so they could see what was involved in the work and manual labour and talk to the workmen. It was part of his idea to teach the children something about social inequalities and the conditions of the working class. At the end of every such excursion Wilhelm had to go up to the man in charge, remove his hat and make a small speech of thanks. When they visited mines and factories he was fascinated to see at first hand the nation’s growing industrial strength, and in later years he claimed that this had given him some insight into social and labour problems. On the other hand, museums and art galleries bored him, despite his feeling for history, and as an adult he veered between the philistinism of his paternal grandfather and a half-hearted attempt to play the dilettante.

On their walks Hinzpeter encouraged Wilhelm to express an opinion about everybody they met. He should never be afraid of expressing his views, the tutor told him, and he should not allow himself to be dominated by anybody, even his most responsible advisers. Such motivation did not prove helpful in the long run. When he was almost eight, his mother wrote to Queen Victoria of her son’s failings: ‘he is inclined to be selfish, domineering and proud, but I must say they too are not his own faults, as they have been hitherto more encouraged than checked’.40

Hinzpeter also helped Wilhelm to overcome his fear of riding. When he watched a groom lifting the Prince gently on to the back on a pony and leading it on the rein, it looked like an admission of defeat. Ignoring the weeping boy’s protests, he made him sit on the pony without stirrups, and told him to take the reins in his right hand. When he repeatedly fell off the tutor patiently put him back, and after several weeks Wilhelm found he could keep his balance. Soon he was developing horsemanship skills which would have been praiseworthy even in a boy with two good arms. He wore a golden bracelet on his left wrist through which the rein could be passed,41 as his hand appeared to hold the reins but had no control over the horse, which was specially trained to respond to knee pressure. For a future sovereign to be afraid of horses was not necessarily a disgrace, as his near-contemporary, the Tsarevich of Russia, later Tsar Alexander III, was a bear-like individual whose physical strength and vast frame belied a terror of riding long before he became too heavy to mount anything other than a carthorse. Yet as second in line to the throne of the most military minded state in Europe, Prince Wilhelm needed to learn equestrian skills. But if Hinzpeter had refrained from forcing him to master what had seemed impossible, his charge might have grown up a more balanced character.

The prince had already begun to overcome his disability in another way, while at Balmoral with his parents in August 1866. Walking into the ghillies’ room one afternoon where they were cleaning their guns, he tried to pick up a weapon but it proved too heavy for his good arm. As he was about to throw a tantrum one of the men, without saying a word, gently put a small light rifle that had been the Prince of Wales’ first gun into his hand, and showed him how to use it. This was the kind of encouragement to which he responded best.

On 27 January 1869 Wilhelm celebrated his tenth birthday. He was invested with the Order of the Black Eagle, and allowed to wear the uniform of the first infantry regiment of the guards. Apart from his brother Henry, he had few childhood companions. One of the exceptions was Poulteney Bigelow, fifteen-year-old son of the American minister in Berlin, who was invited to play with the princes at Potsdam in the summer of 1870. He found them good company, especially when they were freed from their tutor’s watchful eye. It was fun to kick footballs along the roof of the Neue Palais, until too many broken panes of glass attracted Hinzpeter’s attention, or playing by the river and sailing a model frigate presented to one of their great-uncles by their mother’s great-uncle, King William IV of England. With hindsight, Bigelow believed that this vessel was ‘the parent ship’ of the future Kaiser Wilhelm’s navy.42 They corresponded with each other until the latter’s death. The American ‘was an uncommonly amiable fellow; amongst us boys he held a place of high esteem because, coming as he did from the “Wild West”, he was able to tell us tales of murder about trappers and Red Indians, and acted as experts in our games of Red Indians’.43

Real life war games would soon intrude on the boys’ consciousness. In July 1870 France and Germany were at war. Within weeks Emperor Napoleon of the French was defeated and abdicated, his empire in ruins, and out of the ashes the new German empire was proclaimed at Versailles in January 1871. It was a promotion which gave no pleasure to the newly elevated but intensely touchy King Wilhelm of Prussia, now German Kaiser, who did not hide his irritation at having to exchange his splendid time-honoured crown for another. Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm sent home captured colours and eagles from the front, and the keys of surrendered cities to his sons. Hinzpeter pinned a large map up on their wall, and together they placed flags on pins to show troop movements and advances as news came back of each triumph. The princes were at Homburg when they heard of the great German victory at Sedan. Cheers in the street and a torchlight procession by the excited townspeople woke them from their sleep, and they got up excitedly in their nightshirts to watch, not realizing that everybody could see them on the balcony. When Hinzpeter gave them an angry lecture the next day for such undignified behaviour they were astonished.

In June 1871 victorious troops from Potsdam made a spectacular entry into Berlin through the Brandenburg Gate. Wilhelm was allowed to take part, riding on a small dappled horse between his father and Uncle Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden. A few weeks later the Crown Princess took her children for a long holiday in England, leaving her husband to recuperate from a viral infection contracted partly through feeling rundown after the war.

There were now six children in the family, the three youngest being five-year-old Victoria, three-year-old Waldemar and baby Sophie, just a year old. With the birth of a fourth daughter, Margrethe, in April 1872, the family was complete. Unlike their Hohenzollern cousins, the children were small and rather weak. In the nineteenth century parents, royal and otherwise, were proud of fat children as they believed that when their infants were sick, the more weight they had ‘to draw on’ the better. At about 5 ft 2 in the Crown Princess was hardly taller than her own mother, though the Crown Prince stood almost a foot above her. Always sensitive to criticism of the children from her in-laws, the Crown Princess was furious with her husband’s cousin Prince Friedrich Karl, who did not hesitate to voice his unsolicited personal opinion that a one-armed man should never be allowed to become King of Prussia.44 The boorish Friedrich Karl and his equally unpleasant father Karl, the Kaiser’s brother, had always viewed with contempt the Crown Prince, firstly because of his bouts of ill-health in childhood and their belief that they would provide more robust monarchs of Prussia, and secondly because of his more liberal, artistic leanings. At Court they were among the most outspoken opponents of the Anglo-German connection, and an unfriendly rivalry between both lines of the family would always simmer just below the surface.

Crown Prince and Princess Friedrich Wilhelm and their children spent every winter in Berlin, the summer in Potsdam and a holiday in July or August, if possible, in England or occasionally perhaps in Holland, where the bracing sea air was considered healthy for them. At home the children took breakfast with their mother and father, and the younger ones came to their parents’ room at 7 a.m. while they had their cup of tea and toast in bed before getting up. Though she was always busy, recalled her second daughter Victoria, the princess never neglected the family. ‘Every moment that she could spare away from the various duties which devolved upon her was spent with us.’45

The Crown Princess was keen to remove her eldest son for a while from the martial, celebratory atmosphere of post-war Berlin, as she feared it might have the wrong effect on him. In January 1871 she had written to Queen Victoria that her son had the Prince of Wales’s ‘pleasant, amiable ways – and can be very winning. He is not possessed of brilliant abilities, nor any strength of character or talents, but he is a dear boy and I hope and trust will grow up a good and useful man.’46