4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

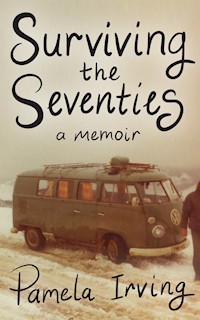

- Herausgeber: Pamela Irving

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Flared skirts, beehive hairdos, stay-at-home mums ... Australia in the fifties and sixties was comfortably conservative. Then along came the seventies ...

This is the story of how one young Australian navigates her way through a decade of upheaval.

It's 1971, past midnight on a cold Sydney winter's night and Pamela finds herself alone in the darkness on the side of a deserted highway with no money and no idea where she is. She's just escaped an abusive relationship and so begins her life as a single parent, living in communal houses, racing across the city between child-care and work and home, saving for her dream of travelling the world.

Drug-dabbling along the Hippie Highway in Asia, battling homelessness in London, living in France and Greece in a rusty old Kombi van, Pamela hones her survival skills. And all the while surpassing Bridget Jones in her selection of unsuitable men.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

About Surviving the Seventies

It’s 1971, past midnight on a cold Sydney winter’s night and Pamela finds herself alone in the darkness on the side of a deserted highway with no money and no idea where she is. She’s just escaped an abusive relationship and so begins her life as a single parent, living in communal houses, racing across the city between child-care and work and home, saving for her dream of travelling the world.

Drug-dabbling along the Hippie Highway in Asia, battling homelessness in London, living in France and Greece in a rusty old Kombi van, Pamela hones her survival skills. And all the while surpassing Bridget Jones in her selection of unsuitable men.

Contents

A stone’s throw out on either hand

From that well-ordered road we tread

And all the world is wild and strange.

In The House of Suddhoo

By Rudyard Kipling

I’m running down the footpath beside Blues Point Road in North Sydney. I’m shaking violently. My heart is beating through my chest. Every cell of my body is bursting with terror. It’s after midnight in the middle of winter. The street is deserted.

I can hear his footsteps gaining on me. I’m wearing shoes with two-inch chunky heels. Not stilettos, thank God, but running shoes they aren’t. I feel his hand clamp my shoulder, and I’m thrown on to the road.

We are outside a block of flats and I break away and run inside up the stairs. He catches me on a landing and pulls me to the ground. I am screaming to waken the dead but the doors of the flats remain tightly closed.

He pulls me back to the footpath. I look around in desperation but the street remains empty. He tries to drag me back to the car but at five feet eight I’m not much shorter than he is, and he isn’t strong enough to carry me.

A car pulls into the parking area, spotlighting the road. Hope pushes terror aside. I scream for help.

I get up and run to the car. My right ankle keeps collapsing. My shoe is loose, trailing flimsy ribbon ties.

I am aware of my assailant running back to his car parked at an angle in the middle of the road, its headlights still shining, the driver’s door wide open.

Chapter 1

“I’ve just had a terrible fight with my boyfriend. I’ve got to get to Epping. Can you take me?” I sob through my saviour’s open window. The startled face of the driver, a conservative-looking man in his mid-forties, stares back at me. “Just wait here a minute.”

He parks the car and disappears into the building. I assume he’s gone to explain to his wife this drama he’s got himself caught up in. When he comes back down, I get into the car and we set off for Epping.

I explain the bare bones of my predicament. “We had a fight. He’s got a terrible temper.”

We continue along for a minute or two in silence. “Would you like to have a cup of coffee somewhere?” he asks.

“No, I’ve got to get to my friends’ place. It’s late. They’ll already be in bed.” Anxiety at waking Hans and Heather so late is rising up in me.

A couple more minutes of silence follow. The car has bench seats, not the two separate front seats of later cars. He pats the seat next to him. “Do you want to move over next to me?”

I’ve never been able to think on my feet but my guardian angel steps in for the second time that night. “Stop the car, stop the car. I feel sick. I’m going to be sick.”

He wrenches the car to the curb and before it stops I am outside on the footpath.

“Thanks for the lift,” I say as I slam the door. My rescuer-cum-molester rapidly turns the car around and speeds off back the way we came.

I’m on the side of a major road and it’s pitch black. I have no idea where I am. There are no cars coming in either direction, but I’m not about to repeat the last episode anyway. I look up and down the road. Shall I start walking? In which direction? Shall I hide somewhere and wait until morning?

As I stand, my mind a blank, in steps my angel again. A taxi approaches from behind. In no time I’m in the doorway in front of the bewildered Hans and Heather, garbling my explanation between tears. Heather has to write a cheque for the taxi driver. Everything I own is back with Ken in his boarding house.

*

Self-preservation kicked in. I went to a CHUMS meeting: Care and Help for Unmarried Mothers. The politically incorrect name of the group mildly embarrassed me then. Now it makes me wince. However, unfortunate labels aside, it turned out a god-send. How had I, this well-raised, well-educated, conservative Adelaide girl ended up in Sydney, a penniless single mother, the victim of domestic violence?

The stories of the other young women in the group fascinated me. They were in their teens, twenties and thirties, and from right across the social spectrum. I started to feel not so alone. I told my own story, how I’d met Ken, a sailor just back from Vietnam, at a summer wedding in Adelaide. He’d been good fun, in party mood after months in Asia on the ship. He had a great smile, beautiful white even teeth and curly dark hair which fell across his brow. Exotic, with an Indonesian father. I wasn’t particularly looking for a permanent partner – I was finishing my course in Medical Technology and had plans to sail to England the next year.

Ken, however, was ready to settle down. His own childhood had been traumatic. His mother had left his violent father and Ken ended up in a Salvation Army Boys’ Home, considered uncontrollable. His two previous relationships had ended with the girls leaving him, and he was determined the same thing wouldn’t happen with me. Our relationship was conducted between Adelaide and Sydney where Ken’s ship, the HMAS Brisbane, was based. It was a novelty to have an interstate boyfriend. We drove back to Sydney together on one occasion – it was a buzz to see the Harbour Bridge as we arrived at dawn. I wore a long white gown with small black polka dots to the Brisbane annual ball. I caught the bus to Melbourne, Ken drove, and together we explored the city. My housemates and I met Ken in Canberra and we drove around admiring the mansions housing international diplomats.

Ken was due to go back to Vietnam the following March, and I planned to go to England that April. I vaguely imagined we’d meet up sometime when his tour of duty finished, and see how things went then. I knew his feelings for me were stronger than mine for him, but I was just going with the flow, letting the universe take care of things. I was living in a share-house with three friends and – what with work, study, relationships and travel – life was good.

He started regularly driving across on weekends with some of his sailor friends. Was it normal to drive nearly a thousand miles each way every couple of weeks just to see your girlfriend? Ken always seemed happy, easy-going, generous… but I started to feel vaguely uneasy.

*

Then my world changed forever. I found out I was pregnant. I waited till Ken arrived the next weekend to tell him. I looked at him as he stood in the doorway of my room, and in an instant I knew I couldn’t stay with him forever. But Ken was the first to drop a bombshell. “I’m not going back,” he said. He’d deserted from the navy.

I listened as he told me of his decision to leave. Efforts to get a shore posting had failed, and he didn’t want to go back to the isolation of Vietnam. He’d told me several times he didn’t want me to go to England. “English guys aren’t that good,” he’d said. I immediately understood the reason he’d deserted was because he feared our relationship would end if he went away.

I went into survival mode. I didn’t consider a termination. Abortions were illegal in Australia back then, and after working in the Royal Adelaide Hospital and seeing the results of illegal abortions, I wasn’t going down that path. The memory of an Italian girl who’d tried to abort herself with a sliver of wood, contracted tetanus and ended up in an iron lung was enough for me. After an illegal abortion, there was always the chance you wouldn’t be able to have more children. I came from a large family and always assumed I’d have kids. I’d been brought up in the Methodist church, and considered terminations murder.

I told Ken we’d have to have the baby adopted as I couldn’t tell my conservative family. Ken took the news of my pregnancy calmly. We made plans to go back to Sydney to live when I finished my course in a few months’ time. Long-term plans weren’t discussed, and I didn’t raise the topic.

Ken’s easy-going manner changed. He seemed critical of everything – his work, my friends, Adelaide and, in particular, me. Through one of my housemates, he’d got a job working as a labourer on a building site. He hated it after so many years in the navy and resented taking orders from his boss who he detested. He helped himself to a box of fancy taps intended for the house which was nearing completion. “Supplementing the income,” he said. I was horrified. I’d never stolen a thing in my life. He had no use for taps, but took them anyway. Eventually he gave them to Hans and Heather in Sydney, for a house they planned to build in Queensland.

I’d just got my driving licence. When we were out driving, Ken would stop the car. “You drive,” he’d order, handing me the keys. There was no point refusing. He’d sit in the passenger’s seat poised like a cobra, watching my every move.

“What’d you do that for? Stop the car. You’re driving like a dick-head.”

He’d insist that I drove in the left-hand lane. “But there are always cars parked there,” I’d object.

“The road rules are you drive in the left lane unless you’re overtaking,” he’d order. Ken was hardly one to follow rules, but this gave him the opportunity to yell at me if I didn’t weave between the lanes quickly enough. This criticism gave him a perverse pleasure.

He’d picked up a spare battery from somewhere and put it in the boot of the car. I had to run an errand while he was at work and the battery, which I’d totally forgotten about, tipped over and spilled acid all over the bottom of the boot. There was hell to pay when Ken discovered it. He knew I was going out in the car, he knew the battery was in the boot but had also forgotten it. Did he always need someone to blame? Or did he get off on muscle flexing? Often I’d be left a list of things to do while he was at work. The abuse would start if I forgot anything. Even my sewing machine had to be put away and all evidence, such as stray bits of cotton, picked up off the carpet before he got home. I was to give him my undivided attention.

The parking area at our Burwood flat was under the building. Huge pillars supported the storeys above. It was always tricky to park the car, dodging pillars and other vehicles. One evening Ken was in the passenger seat as usual, watching my every move. He yelled at me once too often.

“You park it then,” I retaliated. I didn’t see it coming. His fist slammed into my face.

“I hate you,” I screamed as I ran upstairs to the bathroom to wash the blood from my bleeding nose.

To this day I occasionally feel mildly panicked when driving with a passenger.

The easy-going Ken had been an act; the real Ken was into total control. He’d create a scene in shops if he wasn’t served quickly enough, banging on the counter and yelling. I’d stand there wishing the ground would open up. I endured the humiliation of constant criticism in front of his friends. Ken saw me as his possession, bound to him by my pregnancy and financial dependence.

I left two weeks after the baby was born.

Chapter 2

My adoption plans wavered. In the 1960s, most single women who gave birth had their babies adopted. A lot chose to do so – the stigma of being an unmarried mother still stuck firmly. Some were pressured or forced to relinquish their children. A part-Aboriginal woman who I met at CHUMS had a little girl of about four. Her first child, a boy, had been forcibly removed in Papua New Guinea. However, by now it was the early seventies and a lot had changed in a few short years. All the women in the group felt the choice was now theirs. Gough Whitlam’s Supporting Mother’s Benefit wouldn’t be on offer for another year or so, but somehow we managed. My most pressing priority was to get accommodation.

At a CHUMS meeting I met 18-year-old Linda who had a two-year-old, Becky, whose father was in prison. They’d been in a relationship since she was 12. He’d been part of the Darcy Dugan gang, a notorious Sydney bunch of criminals. Darcy had the dubious honour of being New South Wales’ most infamous prison escape artist. In 1946 he was being transported by prison tram between Darlinghurst Courthouse and Long Bay Gaol. As the tram passed the Sydney Cricket Ground, he cut a hole in the roof with a kitchen knife and escaped. The tram can be seen today at the Sydney Tramway Museum, presumably with the hole unrepaired… On the wall of the last cell he escaped from he’d written “Gone to Gowings”.

Linda had run away from home to join her boyfriend in the gang, leaving her frantic family searching for her. Even her detective sergeant stepfather couldn’t find her. Eventually, after Becky was born, Linda rang her mother and came back to her family. However, now she was anxious to move out of the home she shared with her mother and stepfather. She and her mother had too many fights. Linda told me that Darcy was a “real nice guy”. I got the impression Linda was proud of her association with criminals – it gave her some sort of anti-hero status among her friends.

Linda and I didn’t exactly have a huge amount in common; our age difference alone would normally have cancelled each other out as flatmates. However single parents looking for accommodation were thin on the ground and we didn’t have the luxury of shopping around. We found a two-bedroomed flat tacked onto the back of an Italian family’s home in Ashfield. I didn’t want to live in the Inner West. Ken and I had started off living in Burwood in January 1971 when I first came to live in Sydney. Ashfield, the next suburb, was a bit too close to those bad memories. But beggars can’t be choosers. Linda had found a government childcare centre for Becky in Redfern, and wanted a place near the railway line.

Linda also got me a job working with her for Telegene, a company with a band of workers who dressed in brown uniforms and cleaned telephones all over the city. But was it effective? Immediately after cleaning, the next user wouldn’t catch anything. But what about the following person? And we only cleaned each phone once a fortnight. I considered it a service for companies with more money than sense. Linda and another girl used to while away their time in various Sydney parks instead of cleaning the phones. They were never found out. However, I didn’t have to ponder on this too long. After two or three weeks I got a job in a private pathology laboratory in Surry Hills. I’d finished my studies but still had a few months of employment to fulfil the practical side of my traineeship. I would soon have my Diploma of Medical Technology after five long years.

But now it was time to get my baby son back. He’d been in a babies’ home in Adelaide for the past two months. I’d gone back to Adelaide two weeks after Danny was born. Ken had reluctantly agreed. I was in a highly anxious state, in a disastrous relationship. My mother and father, oblivious of the fact they were grandparents, had to be told.

Chapter 3

After the dust had settled, I needed time to decide what to do. Going back to Ken was out of the question. I was confident I could bring Danny up myself – after all, I had a brother and sister considerably younger than me, and knew all about caring for babies. But should I? Would he be better off adopted into a two-parent family? Would I be better off free to follow my dreams? I needed time to think. I used what was left of my precious travel savings and went on a package trip to Fiji. Not quite the long boat journey to England I’d dreamed of…

Danny was to be left in the care of the babies’ home. The administrator who discussed my situation with my mother and me walked with a limp and was very kind. She said because of the disability she’d been born with, she’d decided not to marry, and had devoted her life to caring for babies in need. I wiped away the tear that was rolling down my cheek. She said that because I was such a nice girl I’d be sure to marry and have more children. What a contrast to the attitude to single mothers in the not so distant past.

*

Fiji was different from anywhere I’d ever been. In my 22 years I’d lived in South Australia and visited New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Victoria and the southern part of Western Australia. This was my first taste of the tropics. I stayed on Castaway Island, off the main island, Viti Levu. There was a handful of people my age and we went water-skiing every day. Water activities were part of the deal and we went out in a glass-bottomed boat to see the coral reefs. Some of us were deposited on a reef to snorkel while the boat took the others further afield. I was paired with an older American guy. We adjusted our goggles and snorkels and swam slowly side by side. The first thing we saw was a shark. I did the proverbial walking on water, but at four-minute-mile speed. This was not my first experience of swimming with sharks.

When I was a kid in Adelaide, I sometimes went for a swim on summer evenings with our neighbour Mrs Venn when she got home from working in her little milliner’s shop opposite Brighton railway station. This particular evening was no different. We walked down the road to the steep path which led to the beach and a few minutes later were wading through the shallows over sand banks and out into water deep enough for swimming. The evening was still and warm, the sea like a mirror. Marino beach is at the end of a long, white sandy beach which stretches away to the north for miles up the coast. To the south lie headlands and rocky beaches. Perhaps because of the abrupt change from sandy beach to rocky headland there are sandbars which extend out to sea. We were a long way from the shore before we reached deep enough water. I loved to swim, and was soon practising my breaststroke.

I heard Mrs Venn yell out, “What’s that over there?” She grabbed my shoulder and pointed behind me. I started screaming. About 20 yards away, a large brown fin was cutting through the water straight towards us.

Mrs Venn headed towards the shore, her rotund body ploughing through the water. I was transfixed. I clenched my fists up under my chin and continued screaming. She came to her senses, turned back and grabbed my arm and headed back towards the shore. It felt like we were wading through wet cement.

“Is it still coming? I can’t look,” gasped Mrs Venn. I looked back. The fin was following us in, still the same distance away, ripples spreading out behind in the calm water in the evening light. The strip of white sand was still way in the distance.

An age passed before we collapsed at the water’s edge. Our chests were heaving. When we’d recovered enough to speak, Mrs Venn realised the gold filling in her front tooth was gone. She’d bitten it out in terror. It now lay on the sandy bottom of the sea.

No wonder I had a major panic attack in Fiji. Our salvation, the glass-bottomed boat, was even further away than the sandy Marino beach had been. However, I calmed down when my buddy caught up with me. In reality, it was a very small shark and probably a harmless reef shark. Not like the man-eaters of the South Australian coast where great white sharks like to breed. And to this day I still can’t watch Jaws.

I don’t think I spent my time in Fiji doing much agonised decision-making about whether or not to keep my son. No writing of positive and negative lists. At a very basic level, I felt he was mine. I was the one who had carried him in my body for nine months. And endured the hell of childbirth. Why should I give him away to someone else? He was my son.

*

I’d arrived back in Sydney from Fiji virtually penniless. Before I met Linda and moved to Ashfield, I stayed in the People’s Palace, a very large Youth Hostel-cum-backpackers affair, but for people of all ages. Basic but cheap. In no time I was flat broke and didn’t eat anything for the two days before my first pay from cleaning telephones. When I got paid I went to the Coles Cafeteria and piled food on my tray. However, two days with no food had dulled my appetite and I reluctantly had to leave most of a sponge slice glistening with red jelly.

Linda came with me to the airport to pick up Danny, who was being flown over in the care of an air-hostess. Ken turned up too, which created yet another anxiety-filled episode. It was my own fault; I should have changed the flight time of the plane and kept Ken in the dark. But I’d been brought up to be responsible for, and feel guilty about, everything. As the elder daughter with three brothers and a sister, it was my role to be my mother’s second-in-command. She would never have allotted that role to the males of the family. Back then it was the conservative post-Second World War period and gender roles were well defined. Guilt-ridden at having torn his family apart, I was trying to work something out with Ken. I would never go back to him, but Danny was his son and we both lived in Sydney. Ken could be part of his son’s life. Desperate to salvage something of our relationship, Ken paid for the airline ticket for Danny’s return.

Linda and I, with Danny in his carry basket, got a taxi home, leaving Ken at the airport. Danny was two months older, chubby and smiling. He’d changed a lot since I’d seen him last. Linda gooed over the baby. She was only 16 when Becky was born but it hadn’t put her off babies. I was in a quandary. Ken was Danny’s father but my vague plan of Ken being part of Danny’s life seemed impossible.

My mind drifted back to that night at Ken’s boarding house in North Sydney, the night I’d ended up running for my life in the darkness along Blues Point Road. I’d gone there to talk to him in the hope we could work something out. Our baby would soon be back in Sydney. He had to accept that our relationship as a couple had finished, that we had to figure out where to go from here. It started off pleasantly enough, but suddenly Ken snapped. Perhaps he finally accepted I wasn’t coming back. He was in tears. How could I have led him to believe we’d stay together as a family? All the time I was pregnant, how could I have been plotting to leave him?

I was guilt-stricken. Why didn’t I defend myself? Had a life of feeling responsible for everything made everything my fault? I had never said I’d stay with Ken. He’d just assumed I would. It had never occurred to him that I could leave.

“You had me in tears every day. Didn’t that tell you anything?” I countered in defence.

“I don’t know anything about women, I’ve been in the navy since I was 16,” he said.

That at least was true enough.

In an instant, Ken had me pinned to the bed, his hands around my throat. I felt his grip tightening. I was in absolute terror. I looked into his face. It was the face of a stranger. Utterly cold and determined, his dark eyes piercing mine. A vision of my baby son with a murdered mother, and a father in gaol, flashed through my mind. I struggled in desperation, but the soft bed engulfed me. I couldn’t push myself up. But once again my guardian angel saved me.

“We’ll give it another go, Ken. We’ll give it another go.”

It was the only thing I could have said to stop him. He released his grip. I sat up, shaking uncontrollably. My hands instinctively rubbed my throat. My mind was racing. I had to get away. The toilet was outside the building, a little away from Ken’s room.

“I’ve got to go to the toilet.” As soon as I got outside, I started to run.

When Ken caught up with me in the car and pulled me onto the road, the first thing he said was, “You lied, you bloody bitch.”