13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

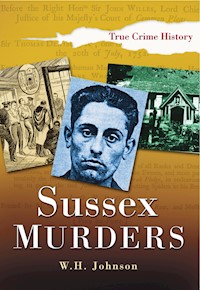

Contained within the pages of this book are the stories behind some of the most notorious murders in Sussex's history. Based upon contemporary documents and illustrations, Johnnie Johnson re-examines some of the crimes that shocked not only the county but Britain as a whole. Among the gruesome cases featured here are the mystery man who shot his wife and three children in a house in Eastbourne, the Chief Constable who was bludgeoned to death in his own police station; the fearsome gang of smugglers who tortured and buried one of their two victims alive and threw the second to his death down a well; and the waiter who danced away the days while his lady friend's body lay mouldering in a trunk in his lodgings. All manner of murder and mystery is featured here, and this book is sure to be a must-read for try crime enthusiasts everywhere.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Sussex

MURDERS

W.H. Johnson

First published in 2005 in Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© W.H. Johnson, 2010, 2012

The right of W.H. Johnson, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8435 8

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8434 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The Murders of Chater & Galley

Harting Coombe & Lady Holt Park, 1748

2. Sally Churchman’s ‘Snuff’

Broadbridge Heath, 1751

3. The Body in Gladish Wood

Burwash, 1826

4. The Dismemberment in Donkey Row

Brighton, 1831

5. Fagan’s Last Case

Ringmer, 1838

6. All for a Roll of Carpet

Brighton, 1844

7. The Onion Pie Murder

Gun Hill, 1851

8. The Enys Road Murders

Eastbourne, 1912

9. When Two Strangers Met

Portslade, 1933

10. The Dancing Waiter

Brighton, 1934

11. The Arundel Park Case

Arundel Park, 1948

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My grateful thanks go to: Alan Skinner of Eastbourne for his photography and his driving; John Dibley for his energetic pursuit of details of the police career of Francis Fagan; John Kay for his 1986 article in Ringmer History 4, which was the basis of the chapter on the Ringmer case; Paul Williams for his Murder Files service which, as ever, has saved me much research time; Jonathan Goodman for his compelling talk on the Brighton Trunk Murders at the Police History Society’s 1993 conference; Simon and Stephanie at The Wheel at Burwash Weald for the nineteenth-century photograph of the pub; Gordon Franks for sending the material relating to Henry Solomon; Andy Gammon for so willingly and speedily providing a photograph of the Law Courts at Lewes; Vivien Burgess for her help with the illustrations; the staffs of the East Sussex Record Office and the West Sussex Record Office; the staff of East Sussex Libraries service and particularly those at Lewes and Eastbourne; the staff of the Brighton History Centre; and all those who initiated the Brighton Police Museum.

None of the above is in any way responsible for any flaws, misinterpretations or inaccuracies in the following pages.

INTRODUCTION

Each of the murder cases dealt with in this book occurred in Sussex but they could have taken place anywhere at any time. Only one achieved national notoriety; others had no more than a fleeting local fame. Several of them have not previously appeared in book form, although, if only for a brief season, they filled column inches in the press and have since been forgotten. But they deserve to be better known.

All of these cases have their highly charged, dramatic moments, which is one of the fascinations of murder. In these pages, John Holloway goes about his awful work in the cottage at Donkey Row; in Gladish Wood, two men, one a grieving father, carry a corpse at dead of night; and at Sherry’s, Toni Mancini dances the hours away, keeping the secret of his lover’s fate to himself. And there are poignant moments, too, as when we catch only the most fleeting glimpse of Mrs Probert, listening to the judge pass the dread sentence on her husband or when we sense betrayal of trust as at Gun Hill, where poor William French goes home looking forward to his supper just as, years earlier, James Whale at Broadbridge Heath had trusted his young wife and her hasty pudding.

For most of us, distanced from such events, there is some challenge in trying to analyse the motives of those who murder and the risks they take in the commission of their crimes. The deaths of Galley and Chater, both old men, serve as an example of eighteenth-century organised crime protecting its empire, but this vile crime is also a more universal illustration of how some men enjoy cruelty for its own sake. Even so, in some of the cases, any satisfactory conclusion is difficult to arrive at: could we ever come to an understanding of the events leading up to the deaths of five people in a house at Eastbourne? What can have lain behind the actions of the man known as Robert Hicks Murray?

There are other mysteries, too, unsolved cases, some with outcomes that after so many years still leave doubts. How Joan Woodhouse met her end in Arundel Park is still a subject of debate; at Ringmer pond there remains the question: did she slip or was she pushed? And what about the weakly youth, Fred Parker? Ought he to have hanged? How much blame attached to him for the brutal killing of an old man?

What is it that leads us to want to know more about these people, some of them, though not all, wicked and cruel beyond belief? Can it be that in studying them, their motives, their situations, we learn something more about ourselves and our own lives? Is it that through them we can sometimes address our own darkest thoughts, peering over a precipice into a pit where we vaguely discern some meaning from their disturbing deeds?

Perhaps it is simpler than that. Whatever murder is, there is no escaping the fact that it frequently offers a compelling narrative. I hope that the chapters that follow will demonstrate this.

The front cover of a 1749 pamphlet which recounted the sorry tale of William Galley and Daniel Chater.

1

THE MURDERS OF CHATER & GALLEY

Harting Coombe & Lady Holt Park, 1748

There is a myth that tells of a Merrie England, of some Golden Age when the English countryman, that Noble Savage, dwelt in peace and harmony with his neighbour. Perhaps in the great cities, the Londons, the Bristols, there was vice, corruption, brutality, but, so the story goes, in the pastures and sheepfolds, in the villages and market towns, the idyll was undisturbed.

Not so. Not in any century. And not in Sussex nor in its adjoining counties. Yet the romantic gloss of the old tales remains. We hear of gallant highwaymen, though these were few. We learn of daring pirates (naturally our own and not the dastardly French) and, most romantic of all, daring smugglers. But none of these bears much scrutiny and all that is required to dispel the legend of smuggling is to recount the last days of Daniel Chater and William Galley, victims in 1748 of what must rank among the vilest murders in the calendar of crime.

For centuries a brisk smuggling trade operated between France and the south coast of England. It developed into a highly professional, greatly sophisticated commercial venture, employing thousands of people – an estimated 20,000 in Sussex – at different levels, from the young farm lads who loaded and lifted the incoming and outgoing goods to those who led teams of pack horses by hidden ways from one safe house to another, from barns to midnight churchyards. There were the armed escorts, men with cutlasses and horse-pistols and heavy batons, all fit and ready to take on the military or the riding-officers who might dare to hinder their progress. And truth to tell, not all wished the trade to end, for how else could they have cheap tea, spirits and tobacco?

Such operations, carried on all over the southern counties, could never have succeeded without an intelligence web to support them, and such systems cannot operate without money to corrupt the forces of law. Out of this huge industry massive fortunes were made. Small wonder, then, that the great corrupt framework on which smuggling depended was held in place by the most ruthless treatment of any who might seek to bring it down. This great criminal conspiracy was sustained by a merciless violence. The murders of Chater and Galley were supreme examples of the smugglers at their worst. But it was these murders that were to break the Hawkhurst Gang, the leading group among the loose confederation of smugglers across Kent, Sussex and Hampshire.

It was this murder that seemed to coincide with the belated determination on the part of the authorities to bring the smugglers to book for they had become far too powerful. Parliament had commissioned a report in 1745 into ‘the most infamous practice of smuggling’, for it appeared that the smugglers were now a law unto themselves. ‘The smuglers [sic] will, one time or another, if not prevented, be the ruin of this kingdom.’ At last it was recognised that the general peace of the country was endangered by bands of men who ignored the law and those who endeavoured to implement it.

In August 1747, only months before the murders, a correspondent in Horsham writes, ‘the outlawed and other smugglers in this and the neighbouring Counties are so numerous and desperate that the inhabitants are in continual fear of the mischiefs which these horrid wretches not only threaten but actually perpetrate all round the Country side’. Even so, some of the smugglers were regarded as local heroes by many; they were cult figures; they were famous, bold; they defied authority.

For example, they carried out an audacious plan in the autumn of 1747. On 4 October, men from the Hawkhurst gang, led by Thomas Kingsmill, met in Charlton Forest near Goodwood to concoct a scheme with a group of Dorset and Hampshire smugglers. Two days later, at eleven o’clock at night, after a second meeting at Rowland’s Castle, thirty smugglers mounted guard in the area leading to the Customs House at Poole while another thirty, armed with axes and crowbars, broke in. Imagine the nerve of it! They smashed the locks, wrenched off the bolts, hammered down the doors and made off with thirty hundredweight of tea valued then at £500. It was rightfully theirs, they claimed. The tea and thirty-nine casks of brandy and rum which they had, weeks earlier, bought in Guernsey had been seized at sea by a revenue ship on its way to the Dorset coast and lodged in the Customs House. But wasn’t it really their property? And how dare the customs service take it from them! Their mission accomplished, the men rode off triumphantly, each carrying five 27lb bags of tea.

Smugglers break open the Customs House, Poole, 1747.

Later in the morning, many villagers along the way turned out to greet the gang of mounted rascals as they passed, to wave and cheer them as they rode unhindered along the road. And it was at Fordingbridge, where they paused for breakfast and adulation, that Jack Diamond looked into the crowd and spotted the shoemaker, Daniel Chater, a man he had worked with on the harvest some time past. Diamond shook the old man by the hand and gave him a small bag of tea. It was the first step towards Chater’s murder.

By the time the local authorities had roused themselves there was no sign of the smugglers but their coup echoed throughout the south. The Government might make noises about the smuggling trade, about its pernicious effects, but it seemed as deep- rooted as ever, quite beyond control. And local people were tight-lipped, many of them grudging towards the authorities, others mindful that if they told what they knew they would suffer, for the smuggling gangs showed little mercy to those who passed on information about them. Nevertheless, the authorities went about their business in the hope that something might emerge. And it did. Daniel Chater did not keep quiet about the bag of tea he had been given by Jack Diamond. Perhaps he bragged that he knew one of the great men, said that he was an acquaintance of one of those who had been to Poole. Even the dissolute great attract admiration.

But by February of the following year Jack Diamond was arrested and lay in Chichester Gaol. Whether he was there as a result of Chater’s boasting and blabbing is unclear. After all, there was a reward of £500 on the head of each man who had broken into the Customs House, so perhaps this had led to Diamond’s arrest.

Customs service officers now called on Chater. They had heard that he had spoken to Diamond at Fordingbridge in the company of the other smugglers, had been told that he had received a packet of the contraband tea. That being so, Chater was told, he was required to identify Diamond formally and then to swear before a magistrate that he had been carrying tea and had been armed. At some later time he might be required to appear in court as a witness.

Chater had not known that it might come to this. He had never been prepared for such an eventuality, to swear to the identity of a lawbreaker. He was aware of the possible consequences of giving information of this nature and we can imagine his reluctance to play the part asked of him. But what were the alternatives? He would be prosecuted, would himself be sent to gaol. He would be safe enough, Chater was reassured. He would have the backing of the law, he was told. He would be given some protection.

The laxness of those who wished to use Chater as a prosecution witness in a major case of organised crime is astonishing. Witness protection was paramount and past experience ought to have been enough to warn those responsible that Daniel Chater was in very real danger. As it was, Chater set out on the biting cold morning of Sunday 14 February, protected by one unarmed man, an equally aged minor customs official, William Galley, with no previous experience of protecting a witness. Perhaps had these two men, who were to meet such horrific deaths, taken care to plan their journey they might not have fallen into the clutches of such wicked people as they did. But they did not know their precise route and they strayed by chance across the paths of their murderers.

The plan was that they should travel to Stanstead and there hand over a document to Major William Battine, a magistrate and the Surveyor General of Customs for Sussex. But at Havant they were lost. Stanstead? In an age when few travelled far they probably asked directions several times and possibly received as many differing answers. But Rowland’s Castle seemed a reasonable proposition and, wrapped up in their greatcoats, with an icy wind blowing, they made their miserable way northwards. At the New Inn at Leigh they stopped off for a drink to warm their bones.

Perhaps the warmth of the pub cheers their spirits, for Chater shows the important letter he is carrying to other customers. And Galley, perhaps not wishing to be outdone, may emphasise his significant role in looking after a man who is likely to be a star witness in an important forthcoming trial. But they cannot help chattering, either of them, and they bid farewell to their audience and continue on their cruel and bitter winter journey.

Sometime after midday it is time for another halt, for they have been on their way for several hours and are yet again chilled to the bone. At Rowland’s Castle they stop off at the White Hart and call for a tot of rum. Would that they had never called here. Would that they had never bragged about their mission to the widow, Elizabeth Payne, who has the licence here. They talk and she listens, and then they tell her that it is time for them to be going. But no, she tells them, they cannot leave, not yet; their horses are in the stable and the ostler has just gone off with the key. He’ll be back shortly, she says, so why not have another drink? What else can they do? So they charge their glasses once more. And as they drink and await the return of the ostler, more customers come in. They join the two travellers, have drinks with them, talk about this important business they are on. Then Galley senses something is wrong. He is unhappy, wonders if they aren’t giving too much away, wonders if Chater is not talking just that bit too much. And why has the ostler not returned? One man, named Edmund Richards, has actually drawn a loaded pistol and pointed it at those drinking and said, ‘Whoever discovers anything that passes at this house today, I will blow his brains out.’ The other customers are now told to leave. What can this mean? But along comes the Widow Payne, telling them all to cheer up and have another drink.

Out in the yard where he has gone to relieve himself, Galley meets one of those who have been with them for the last hour or so. This is William Jackson of Westbourne. They have words. Galley says that he thinks that the witness is being interfered with and he pulls his warrant card out of his pocket. He is acting ‘in the King’s name’, he says. He is a King’s officer, he tells Jackson, and writes down his name in his note book. But Galley has no authority here. Perhaps he is already drunk. ‘You a King’s officer?’ Jackson shouts at him. ‘I’ll make a King’s officer of you. For a quartern of gin I’ll serve you so again!’

Galley (1) and Chater (2) are put on one horse by the gang of smugglers near Rowland’s Castle.

Certainly an hour or so later both Galley and Chater are dead drunk and are carried off to bed. The letter that Chater has flourished so proudly is taken out of his pocket and destroyed.

Down in the taproom, those whom the Widow Payne so cunningly summoned earlier in the afternoon now discuss what they are to do with the two men asleep upstairs. They are dangerous company, smugglers all of them, and vicious too. William Jackson, the worst of characters, mistrusted even by those he works with, sits alongside Edmund Richards, ‘a notorious wicked fellow’. And there is also ‘Little Harry’ Sheerman and William Carter, as well as ‘Little Sam’ Downer, William Steel and John Raiss. They are discussing desperate measures. They are agreed that these men cannot be allowed to live. They are at one in that. Yet, remember, an Act of Indemnity has been passed by the government. This Act makes smugglers vulnerable to informers. Anyone, any smuggler, even one in custody, could, if he named past accomplices, receive a pardon and a reward for all his past offences. The gang in the taproom know what their immediate intentions are but they do not know that, within the year, two of those around the table will name names, will betray the others sitting there.

Now all are agreed on everything but how to dispose of the two fellows sleeping off the afternoon’s rum intake. Should they be instantly murdered? Steel suggested that they should get rid of them, and throw the bodies down a local well, but that proposal was rejected. It was too close to home, the others said. What about keeping them permanently locked up? But that was impractical. The wives of Jackson and Carter had turned up and felt at liberty to offer their own opinion on how the matter should be determined. ‘Hang the dogs,’ they urged the menfolk, ‘for they came here to hang us.’

Eventually it was determined that they needed to be taken away from Rowland’s Castle, as far away as possible. And so now, swathed in long mufflers and wearing heavy greatcoats, six of the group prepared their horses. Only John Raiss stayed behind as he had no horse.

Jackson and the others went to the room where Chater and Galley were still asleep. They were aroused by shouts, punches, whips cut into their backs. Jackson raised his topboot and drew his spur across the foreheads of both befuddled men. Still feeling the effects of the rum they drank earlier, the two wretched men stagger out of the bedroom, go down to the taproom and are pushed out into the freezing air of early evening. Blows still rain down on them. They are punched, the two old men; the heavy weighted ends of whip handles fall on their shoulders; they are kicked and cursed and sneered at. They are already bewildered and frightened, these two men who had set off as innocents that morning. No one says that they wept, but they assuredly did. There is no indication that they cried out for mercy, but there can be no doubt that they did.

Of course, their attackers are themselves drunk and they encourage each other in their brutality. Later, during the night, the effects of alcohol will wear off, but their ill-treatment will not lessen. They will continue throughout the long hours of the night and into the following two days to demonstrate not the least ounce of pity or human sympathy. What they perpetrate cannot be excused as the consequence of too much drink. At no point does it seem that anyone of this group had even a moment’s reflection that what was happening was at the frontier of human cruelty.

Galley and Chater are placed up on one horse. Their ankles are tied under the horse’s belly. And they are tied to each other by the legs. And off they set towards Finchdean, with Jackson’s voice calling out almost as they leave the White Hart yard, ‘Whip the dogs! Cut them, slash them, damn them!’

So they make a slow trail across the frost-hard roadway, the gang members taking it in turn to follow Jackson’s injunction. And who can stop them? Who can even know what they do in this empty, wooded, winter-dark countryside? Who can call out at the sight of the terrified victims, whimpering, flinching, striving to escape the blows? What sorts of men are these who cannot feel the slightest pity? When they pass through Woodhouse Ashes, the shoemaker and the customs official fall from the horse’s back and their captors now suspend them beneath the animal’s belly. But then, tiring of this sport, they untie the two and then set them up once more on the horse’s back and give them another beating for their pains. And Galley’s coat, torn now from the blows from the whips, is taken off his back. He will feel the blows even more keenly now. But let him not call out in pain as they pass through Finchdean. Let him not dare. Neither of them must make a noise now, and the pistols are out and levelled at them. And later they slip from the horse again, again find themselves upside down, their bound heels in the air, their heads trailing on the ground.

The two men fall off their mount at Woodhouse Ashes.

Now they are transferred. Galley is shoved up on to Steel’s mount, sitting behind the rider, and Chater is similarly behind ‘Little Sam’. But this does not save them. They are still beaten with the heavy whip handles. When they reach Lady Holt Park, Galley slips to the ground. In his pain the stricken man begs them to do away with him. He can bear this no longer. But they ignore his pleas and lift him up once more behind Steel. Yet again, as they cross Harting Down, he falls off the horse, and this time he is slung over Richards’s horse, and held in place by Carter and Jackson. Galley pleads with them again. ‘For God’s sake, shoot me through the head,’ he shouts. But his captors laugh and Jackson squeezes the old man’s genitals.

It is past midnight now and they have trailed along these roads and lanes and downland paths for six hours. They have called at only one house, an old friend’s place, where they ask if they can stay for a while, but he sizes up the matter, sees the two captives, divines what it is that they intend, and he turns them away.

Shortly after this, in Conduit Lane, Galley slips sideways on the horse, calling out that he is falling. ‘Fall and be damned,’ ‘Little Harry’ Sheerman tells him, and it may be that he pushes Galley so that he falls heavily. When they go once more to remount him they find that he is lifeless. So what now? The body is heaved up on to the horse’s back and the party trudges on.

They make for Rake. Here, at the Red Lion, the owner, William Scardefield, very unwillingly lets them in. He sees Chater, ‘whose face was a gore of blood, many of his teeth beat out, his eyes swelled and one almost destroyed’, and what may be a corpse. They have been in a fight with customs men, Scardefield is told. Some of their men have been killed and others wounded. They explain that somehow they have taken a prisoner or a witness and Scardefield wonders what they intend to do with him. He fears the worst but agrees to allow them to put the man in a hut while Galley’s body is hidden temporarily in the brewhouse. And after some time for further discussion and a drink, Galley’s body is once more thrown across a horse. Scardefield leads the party to Harting Coombe, a mile away. Here, in woodland and by lantern light, the body is buried by Carter, Downer and Steel.

The smugglers prepare to dig a hole in which to bury William Galley.

Then through the hours from dawn until late at night the gang sit drinking in the Red Lion, pondering their next move. From time to time they check that Chater is still in the hut but how can he not be? He is shackled to a post. That does not save him from their taunts, their threats, their kicks. They have not softened in their view of the helpless old man. Occasionally they give him food, but he vomits over himself, a hapless victim. Over the hours not one of the gang has considered if what they are doing can in any way be justified.

But Chater is a problem. Not their exclusive problem, the men tell themselves. After all Jack Diamond is a Chichester man and this whole business is about him. They have done their share, these Hampshire men, why not bring in the Sussex men? And so Jackson and ‘Little Harry’ Sheerman go off to Trotton with Chater in tow, still being beaten with whips across the face and neck as they go along. They have gone to seek out that old smuggling rogue, Richard Mills. He will understand the problem.

The Red Lion at Rake, drawn by C.G. Harper.

And he does. ‘Major’, for that is how he is known, locks the prisoner in a lean-to shed where normally he dries out turf for fuel. Here, on the freezing Monday night, Chater, exhausted and afraid, is placed on a pile of turf and chained to a beam. From time to time, ‘Major’ Mills comes in to taunt him as an informer, telling him that he will not live long. And ‘Little Harry’ and ‘Little Sam’ stand guard and add to the jeers and the blows.

Several of the gang returned to their homes in the course of the Tuesday, fearful perhaps that their absence might arouse suspicion, but on the next day they made their way back, this time with John Raiss, to the Red Lion, where they were to meet ‘Major’ and his acquaintances on the Wednesday evening. At this gathering were several Chichester men: John Cobby, William Hammond, Benjamin Tapner and Thomas Stringer; Daniel Perryer of Norton, ‘Major’ Mills and his sons, Richard and John, and, from Selborne, Thomas Willis. What should they do? How should they kill him? Should they load a gun and level it at Chater’s head and then tie a piece of string to the trigger? Then they could all pull on the string together. That would make them equally guilty. They would not then inform on each other. But that would mean the game was over, and there is no doubt that they were enjoying the game, the suffering, the power. At least it was agreed that the Sussex men should have the responsibility for getting rid of Chater. ‘We have done our parts and you shall do yours,’ Jackson told them. It was decided that Chater should be thrown down Harris’s Well at Lady Holt Park. After all, the well was dry and never used. The body could lie there for ever and no one would ever suspect that a corpse lay there.

Daniel Chater in chains

The gang returned to Trotton, where Chater lay in the lean-to. Tapner lunged forward with his clasp-knife and cut him across the eyes and nose ‘so that he almost cut both his eyes out and the gristle of his nose quite through’. But that was not enough for Tapner, who then slashed him across the forehead. ‘This knife shall be his butcher,’ he shouted, but ‘Major’ Mills was rather more cautious. It was his house, after all. ‘Pray don’t murder him here. Carry him somewhere else before you do it.’

At the well, after another ride in the dark, Tapner placed a short cord round Chater’s neck. No long drop for him, no sharp, sudden breaking of the neck. He would strangle slowly. Then he was made to clamber over the protective fence and pushed to the edge of the well. The rope was tied to the fence and the desperate old man was pushed over, though, because of the shortness of the rope only his legs dangled in the well. And for the next quarter of an hour, half-sitting, half-standing, he choked. And then, before he died, the rope was taken from his neck and he was suspended by the ankles, held upside down over the well by Stringer, Cobby and Hammond. Then, at last, they let him go, head first. Even so, the wretched, still fearful old man did not immediately die. They could hear him sobbing and groaning at the bottom of the well. They threw down two wooden gate-posts and then large flints. Eventually they silenced him. Chater’s suffering had lasted from the Sunday afternoon until the early hours of Thursday.