Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

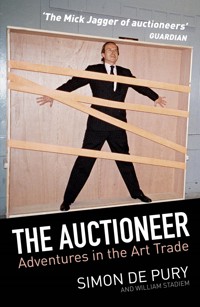

In the glamorous and secretive world of art, Simon de Pury is the ultimate insider. Having elevated the auction into performance art, he is the most famous of all auctioneers. He has been chairman of the global auction house Phillips de Pury, challenging the duopoly of Sotheby's and Christie's. Before that, he was director of the Thyssen Collection, one of the world's greatest private art collections, then the chairman of Sotheby's Europe. For his style, his longevity and his unprecedented success as an auctioneer Simon has been called the Mick Jagger of the art world, but he is also a major collector and dealer in his own right, and a consultant to heads of state and heads of corporations. The Auctioneer gives us a brilliant behind-the-scenes look at the multi-billion-pound international art dealing world - where on a single night a major auction can rack up sales totalling more than £100 million; artists rub shoulders with some of the wealthiest and most powerful people on the planet; and sometimes the buyer really should beware.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain by Allen & Unwin in 2016

First published in the United States in 2016 by St. Martin’s Press

Copyright © Simon de Pury 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral right of Simon de Pury to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 76011 344 5E-book ISBN 978 1 92557 526 2

Internal design by Steven SeighmanCover image: Photograph of Simon de Pury © Courtesy Phillips

To my children: Alban, Charles, Loyse, Balthasar, and Diane Delphine

CONTENTS

1. My Nude Portrait

2. Going Contempo

3. Artopolis

4. L’Artiste

5. The Apprentice

6. London Calling

7. My Role Model

8. The Auction House Wars

9. Simon de Monaco

10. Our Man in Geneva

11. A Royal Courtship

12. Me and the Baron

13. The Merry Wives of Heini; or, The Making of a Collector

14. Foreign Intrigues

15. If I Had a Hammer

16. Teams of Rivals

17. The Women

18. My Oligarchs

19. Courting Medicis

20. The Cutting Edge

Acknowledgments

List of Illustrations

1

MY NUDE PORTRAIT

If anybody needed a rebound, it was I. Professionally, my plans to turn the auction-house duopoly that was Sotheby’s and Christie’s into a triumvirate that included myself had gone up in the terrible smoke and ash of 9/11. I couldn’t have had a greater financial partner than the French luxury-goods tycoon Bernard Arnault, or a greater business partner than my former Sotheby’s colleague turned co-gallerist Daniella Luxembourg. Alas, both the real world and the often unreal art world had been upended in the fall of 2001 by al-Qaida and by the resultant financial terror that shook the confidence of even the most deep-pocketed and geopolitically indifferent collectors. Arnault had gone, and Daniella was going. An incurable optimist, I refused to believe that the ship everyone else said was sinking faster than the Titanic could not be righted and sailed gloriously into the sunset. O Captain! The art world groaned and collectively crossed the street to avoid me, to them a dead man walking, whether the thoroughfare was Madison Avenue, Bond Street, or the Ginza.

Romantically, things were just as disastrous. My wife, Isabel, and I had parted ways. For our decades of marriage I had viewed Isabel as the most intellectually brilliant of women. I next was involved with Louise Blouin MacBain, a female tycoon by whose entrepreneurial gifts I had been smitten. Her power and success, not to mention the Marie Antoinette splendor of her lifestyle, were aphrodisiacal. Her gilded aura surely played into the ambitions I had in wanting to challenge the giants Sotheby’s and Christie’s. But that love affair had gone the fiery way of the Twin Towers, and now I was adrift. I had always found solace, as well as inspiration, in art. Now, at low tide, I found it in an artist.

Anh Duong could surely be said to be the distaff trophy of the art world, and in falling for her, I may have been a victim of the same megalomania that had drawn me to the likes of Bernard Arnault and Louise MacBain. A similar siren call had lured Odysseus to near disaster. The Greeks, as ever, had a word for it. Unfortunately, I didn’t have anyone left on my putatively sinking ship, now christened Phillips de Pury, to tie me to the mast to prevent me from succumbing to whatever fatal attractions the world had in store. Please forgive my delusions of grandeur, which actually did have some foundation in reality. I had been blessed with a fabulous wife, four fabulous children, and a fabulous career, having held two of the plum jobs in art, first as the curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, the greatest private assemblage in the world, only rivaled by that of the Queen of England, and then as chairman of the colossus that was Sotheby’s Europe. I couldn’t help but think big; it was an occupational hazard. And now all the hazards were coming home to roost.

Luckily for me, Anh Duong’s remarkable beauty and talent didn’t add up to her being a femme fatale. Anh was a true exotic, half Spanish, half Vietnamese, born in Bordeaux, educated to become an architect in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts. Instead, she became a ballerina and then a top model, gracing Vogue covers and Yves Saint Laurent and Christian Lacroix runways. She eventually stole the heart of Julian Schnabel, away from his fashion-designer wife, Jacqueline. And now she was about to steal mine, away from nothing at this point but shell shock, loneliness, and the battle fatigue of the challenge of saving Phillips de Pury from its predicted oblivion.

What surely excited me the most about Anh Duong wasn’t that she was a top model, but rather that she was an intriguing artist. She had been encouraged by Schnabel, who became famous for his huge paintings set on broken fragments of ceramic plates. Many consider that Schnabel has one of the biggest egos of any living artist. He boasted about being the next Picasso the way Cassius Clay used to boast that he was the greatest thing since Joe Louis. So the fact that this ego allowed Anh to develop as an artist meant that there was something special there. Schnabel bought her an easel, brushes, and paint, and she began to play around. Eventually she developed a style evocative of Frida Kahlo. Her trademark was her self-portraits, often nude or in transparent lingerie.

Anh and Schnabel had broken up when he went on to marry his second wife, Olatz, a Spanish actress. Anh lived in her studio on West 12th Street, near my new Phillips de Pury offices on 15th Street, where I had beaten a hasty retreat when our disastrous auction efforts had necessitated fleeing from the skyscraper rents on 57th Street. This was well before Manhattan’s Meatpacking District had become the new SoHo, and I like to think I helped plant the seed of cultural gentrification here. I had met Anh at a dinner at Pastis, then the neighborhood canteen, and suggested quite flippantly across the table that I would like to commission her to do my portrait. Equally flippantly, she agreed. Was this a modern version of the old seduction ploy of inviting the object of your affections to come up and see your etchings? I don’t think so. I wasn’t even thinking romance, at least not consciously.

Anh had been developing quite a reputation as a portraitist. She had recently painted the major contemporary collector Aby Rosen, a global realty mogul who had moved to New York from Frankfurt and would eventually buy both Lever House and the Seagram Building, two of New York’s greatest architectural trophy properties. Anh had painted Aby in his boxer shorts. She was currently painting the model Karen Elson, legendary for her pale skin and flaming hair, wearing nothing at all. I wondered what she had in store for me.

These portrait sessions tend to be very long and very intimate. I remember that when Heini Thyssen commissioned Lucian Freud to do his portrait, it took over 150 hours of sittings, over the course of fifteen months in 1981 and 1982.

I wasn’t sure what I wanted in Anh’s portrait, other than that it not take as long as Freud’s of Heini and that it not be in the nude. I requested that I wear my uniform of a double-breasted Caraceni suit, a tailoring obsession I had contracted from my former boss, Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, who was a devoted Caraceni man and had sent me to Milan for my first fittings, after which I was totally hooked. The tailor of kings and the king of tailors, Caraceni had dressed the crowned heads of Italy and Greece, when they still wore crowns, as well as Gianni Agnelli, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, and even couturiers like Yves Saint Laurent and Valentino. I liked being in such heady company, and really didn’t want to be captured for posterity any other way. Matching the suit’s navy color, I wore my habitual navy tie and white shirt and carried my other trademark, my red leather diary from Smythson of Bond Street. Auctioneers are notorious for their superstitions. One of mine was to eat an apple before every sale. Another was always to be bearing something red. Anh was very tolerant of these fetishes.

As we began our sessions, what drew me most to Anh was her striking, observant eyes. They put me on the spot and created a particular tension, which is essential to making art. The other thing that lured me in was that her taste in music mirrored my own. There had to be music in these sessions, and Anh’s mix was an eclectic mélange of opera, classical, rock, pop, French chansons, and movie soundtracks. Every tune touched a chord in me. Ever since childhood my three obsessions have been art, music, and soccer. With Anh two out of three was as good as it would get. Over the course of our sittings something just happened. Anh gave me a sculpture of herself. I ended up buying her Karen Elson portrait for myself. Despite its full frontal nudity, Anh wasn’t the slightest bit jealous. This was art, not sex. Such was Anh’s immersion in la vie bohème, Chelsea version. But art is sexy, as sexy as anything, and eventually something started between us.

Enter Eric Fischl, an artist I have always greatly admired. I saw him as the continuation of the great American realist tradition, the spiritual descendant of Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper. In the eighties, no one was much bigger than Eric. He was up in the stratosphere with Schnabel and Ross Bleckner. The three of them were a juggernaut, the “Boone Boys,” all discovered and represented by the queen of that decade’s SoHo art firmament, Mary Boone, a modern-day commercial Cleopatra, who, most fittingly, was of Egyptian descent. When I was running Sotheby’s in Geneva, I had invited Eric, at the height of hot, to come to Switzerland to be part of my monthly lecture series. Jeff Koons, Karl Lagerfeld, and Philippe Starck were fellow invitees, proof that I was not behind the curve in the emergence of contemporary art and style as the next big thing.

Given the vagaries of the market, Eric has never gotten any bigger than he was in the eighties, nor has Mary Boone. Eric had become famous as the Degas of American suburbia, painting transgressive images of his alter ego staring at his naked sleeping mother in bed while picking her purse (Bad Boy) or that same alter ego masturbating into a backyard swimming pool (Sleepwalker). Eric was anything but bitter, but to pretend that schadenfreude did not exist in art the way it does in Hollywood would be a very Pollyanna-ish perspective. That his works sold in the high six figures rather than the seven he used to sell for or the eight of some of his fellow boy wonders was no one’s tragedy. In fact, to me it was nothing but sheer opportunity. A dealer loves nothing more than an undervalued artist. The fact that I couldn’t afford Eric in the eighties stoked my desire to buy him at bargain prices in the new millennium.

In 2002 I saw a Fischl at a Mary Boone show that I just had to have, in the same way I just had to have Anh’s Karen Elson, and ultimately just had to have Anh herself. The piece was called Living Room, Scene 2, painted in a Mies van der Rohe house-turned-museum in Krefeld, Germany; Eric turned it back into a house and hired actors to do for German suburbia what he had done to that of his childhood in Arizona. Living Room depicted a wealthy couple in their sleek abode with their proudest possessions: a Gerhard Richter, a Warhol, and a Bruce Nauman. That painting spoke to me as a collector and, especially, as a dealer. I went to Mary and bought it on a handshake.

Alas, that handshake quickly went the way of all flesh. Mary called to tell me that she wanted to bail and void the sale. She had gotten another offer from the hot and rising Seattle Art Museum and wanted to take it. Microsoft’s Paul Allen, Mr. Seattle, was a huge benefactor of the emerging art scene in that Nirvana of tech. Mary liked the idea of bringing the mountain to Mohammed. Of the many superstars Mary had represented in her eighties glory days, only Eric and Ross Bleckner had stayed true blue. Schnabel had moved on, as had David Salle, Georg Baselitz, Barbara Kruger, and Brice Marden. Jean-Michel Basquiat was, sadly, dead.

My first reaction was to be incensed and refuse to succumb to Mary’s perfidy. No way, I insisted angrily. A deal is a deal. But no one on earth is as persistent as Mary Boone. She wanted her deal as much as I wanted that Fischl. She came up with a compromise: Back off on Living Room, and I will personally get Eric to do your portrait. They’re very rare, Mary said, selling hard. He only does them for his closest friends, like Steve Martin.

Forget it, I told her. I already had one portrait in the works by Anh. How many portraits did I need? Who was I, Louis XIV? Certainly not after my recent debacles. Instead, Mary was making me feel like Rodney Dangerfield, the great comedian whose trademark was “no respect”. Besides, who wanted a one-man picture of me from Eric Fischl? That would be so boring compared to a real Eric Fischl, whose hallmark is the intense tension between two individuals on the same canvas. To me, Eric was right up there with Lucian Freud in creating that tension. Give me my Living Room or give me death, I declared to Mary and hung up.

Then I began having second thoughts, but not noble thoughts, like Let Mary have what she wants. We’ve both been up and down, and she deserves a break. No, I wasn’t that altruistic or noble. Instead I saw a great opportunity to do Mary a big favor and do myself one as well, by turning this portrait into a real Eric Fischl and not some tribute to myself. My brainstorm was to get that trademark tension by having not only me in the portrait but another person as well. And that other person would be Anh Duong. And Anh Duong would be in the nude. As I previously noted, Anh is one of the only true bohemians I know. She has no false modesty, no prudery. There’s nothing Swiss about her, like the high-propriety people I grew up around.

Anh had done so many nude self-portraits that I didn’t even bother to ask her first. Instead, I pitched the concept to Mary, who loved it. Then I called Eric and pitched it to him, and he loved it, too. Only then did I pitch it to Anh, who said all systems go. Anh had done nudes for other artists, such as Peter McGough, a close friend of Schnabel’s from the eighties, who created the daguerreotype-style Anh Duong, 1917, painting her like a pinup of the Jazz Age. Besides, Eric Fischl and Anh were good friends, and she loved his work.

So out to Montauk we went one summer weekend for our rendezvous with naked destiny. Eric lived in Sag Harbor with his wife, April Gornik, an acclaimed landscape painter. He had fled SoHo and the druggy excesses of being a millionaire artist of the eighties for the relative rusticity of the east end of Long Island, before the hedge-funders moved in. Eric was anything but an effete artist. He was a sporty guy, having traded art for tennis lessons with his pal John McEnroe. He had been a security guard in a Chicago museum in his early years.

Unlike Anh, who worked from life, Eric worked solely from photographs and memory. Eric’s hardcore policy was that I would have no say whatever in the portrait and that I could not even see it until it was done. I had expected that Eric would give very specific instructions for what he wanted from us. Instead, he didn’t tell us anything. “So what do you guys want?” he asked. Anh and I were both clueless. She had undressed and was standing around aimlessly in the nude, while I was standing around aimlessly in my Caraceni suit. Finally, Eric broke the ice by starting to snap an endless series of photos, sort of like the David Hemmings character in Blow-Up, but minus any stage directions, like Hemmings gave to Veruschka. Somehow I noticed a rocking chair on the wooden floor of the studio. I went and sat in the chair. Then Anh, by instinct, came over and sat on my knee. Eric climbed up a ladder and began shooting from above. “My God, I feel like Helmut Newton,” Eric exclaimed. At that moment, I had a flash that this particular angle, this overhead shot, was what would end up as the portrait.

The whole session lasted an hour and a half. Anh redressed. Then we had tea, very demurely, with Eric and April and drove back to Montauk, where we were staying with friends. My relationship with Anh lasted ten months. Our romance ended before the painting was delivered. I had warned Anh that we might not last forever, but Anh had no regrets. What she did, she did for art. That was her philosophy. When I did see the painting I was pleased. It was no portrait. It was a real Eric Fischl. The psychological tension fairly screamed from the canvas, so much so that I wondered if I had ever understood how tenuous my relationship with Anh must have been. I look completely alone, notwithstanding Anh’s sultry naked presence on my knee. There was a total disconnect between us. The work was proof of how artists like Eric can see beyond the medium.

I own the painting, but I never show it to anyone. I feared my friends might have written it off to a midlife crisis, or worse. In 2012, Mary Boone had an Eric Fischl portrait exhibition at her new gallery in Chelsea and asked to borrow it. I said yes, with some trepidation. She hung me, or rather the Fischl, on the first wall, all by itself. It was the first thing anyone saw on entering the gallery. Anh came to see it. She burst out laughing. Mary’s exhibit got a scathing review in The New York Times. The critic savaged the exhibition for painting the 1-percenters. I got defensive for Mary. Didn’t every artist throughout history paint the princes of his time? What were the Medicis if not 1-percenters?

I felt bad for Mary, and I felt bad for Eric. He remains on my list of the ten to fifteen major artists who are under-appreciated. The critic had singled out my portrait for special flaying, describing it as “a blasphemous Pietà”. This was my brilliant idea, and poor Eric was getting all the blame. As for the other portrait, the one that started this whole thing off, Anh did finish that one, too, just before we broke up. It was not her best work. Our initial split was anything but cordial, and I wondered if bad art was imitating bad life. Eventually, we both were able to look back in laughter at how art illuminated the naked truth about a relationship that might have been better left unpainted.

2

GOING CONTEMPO

Contemporary art is the New Old Masters. That’s because there aren’t any more Old Masters for dealers and auction houses to sell. They’re all in museums. The same is becoming the case for Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, which are increasingly rarely found in private collections. And as time goes by, even twentieth-century modern art gets a bit long in the tooth. The Abstract Expressionists, Jackson Pollock et al., seem Old Masterly. In 1998 Christie’s changed the art game altogether by changing the rules, or at least the terms, redefining contemporary as work created, not after World War II ended in 1945, but after the1960s revolution ended in 1970. Even though rival Sotheby’s tried to hold the line at 1945, 1970 became the new “sell after” date.

And sell we have. Thanks to longevity and procreativity, the supply of contemporary artists is infinitely elastic and, notwithstanding occasional episodes of market remorse, has been matched by demand. That demand is best symbolized by the Michael Douglas “Greed is good” speech in the 1987 film Wall Street, inspired by the convicted arbitrageur Ivan Boesky. As Wall Street has gone, so has the contemporary art market. Who, some old-time purists may ask, other than barbarians at the gate would be attracted to such creations as Damien Hirst’s ashtray of cigarette butts, which I had sold at Phillips in 2001 for what was then a world record price of $600,000, a record that has been broken since then by 137—and counting—other works of his.

Or the Jeff Koons Woman in Tub, depicting a headless woman in a bubble bath clutching her breasts as she is attacked from below by a snorkel-wearing intruder. Christie’s sold that for $1.7 million in 2000, after which they dressed half of New York’s unemployed actors in Pink Panther costumes to hype the upcoming sale of the Koons sculpture of the same name. The hype paid. Pink Panther sold for $1.8 million, surprising even Christie’s, whose high estimate was only half that amount. I was the underbidder, for a private collector, on the PP, as well as for the $420,000 Fool, by Christopher Wool. Soon after those underbids, a journalist approached me and asked, flat out, “Aren’t you crazy?” I laughed and told him that I was the fool not to get Fool. The ever-soaring prices have proved me right—and not foolish.

Greed was good, indeed. And so it has remained. Here’s a case in point, one of many greedy nights to remember in the world of top-dollar art. It was spring 2013. Christie’s didn’t feel like an auction house. It felt like a gambling house. The electricity in the muggy May air in Rockefeller Center was akin to that of a big night at the Casino in Monte Carlo. The players, or collectors, if you must, were there from all over the world, high rollers from Russia, Asia, and the Persian Gulf, as well as the home-team Americans. By evening’s end, I realized that my instinct that this would be a huge night had not been exaggerated. A staggering total of $495 million in contemporary art had been sold. Fifteen world records for artists had been broken. It was the biggest art auction in history—to that point.

The largest sale of this enormous evening was the $48 million for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Dustheads. The times were changing, and fast. Just a year and a half earlier, as chairman of Phillips de Pury, the only rival to the Christie’s-Sotheby’s duopoly, I had stood on the podium and auctioned another Basquiat for a then-record $16.3 million. And now I had not just been doubled, but trebled. I had thought that I was pretty hot stuff. I loved setting records. Records are a dealer’s, an auctioneer’s, lifeblood. I was hot, all right. But, as it turned out, things were just warming up. The world that seemed to be crashing in 2008 was having a dramatic V-shaped recovery, if not renaissance. The stock market seemed to be invincible, on rocket fuel, and as stocks went, so did art, and at far greater multiples of propulsion.

In today’s pecuniary scorecard of greatness, the price of an artist’s work is often taken to be the measure of the man. What else could serve as a common denominator for the diverse tastes of Wall Street, Russia, China, and Arabia? By that quantifiable standard Jean-Michel Basquiat is the Van Gogh of contemporary art. These two tortured geniuses have been posthumously elevated into the pantheon of cultural capitalism. I do hope Jean-Michel is smiling down on me from that pantheon, for I am proud to have played a role in making the market for him as adulatory as it has become. It all started just a few years ago, when Phillips de Pury set three world records.

The first, in 2007, was the $8.8 million for Basquiat’s Grillo (“cricket”, the insect, not the game, in Spanish), a monumental-sized (over thirty feet wide) tribute to his Puerto Rican maternal roots. I had been mesmerized by this painting nearly a decade before when I was chairman of Sotheby’s Europe. An Israeli dealer, Micky Tiroche, owned it, and promised to let me sell it one day. I had assumed it was all promises, promises—art hype. Amazingly, Micky came through, and I stepped up my own auction game to do him proud, making the huge sale to a phone buyer at our New York auction. So many of these monster sales are over the phone, with the buyers, famous though many be, insisting on anonymity in their extravagances.

In 2008, I set another record of $11 million, in the New York auction of Basquiat’s own Winged Victory, Fallen Angel. This one was from his annus mirabilis, 1981. This was before he met Warhol and their deep friendship began, at the dawn of his discovery and embrace by the illuminati, yet the works from this year were the cream of his crop. My auction of this piece, sold by an Italian and bought, again, by a mystery phone bidder, was immortalized by the director Tamra Davis, wife of Beastie Boy Mike D, in her documentary Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child. Alas, my stellar performance on the podium would end up on the cutting room floor.

But the only way for Basquiat was up. When in 2009 Sotheby’s beat my last record, the competitive adrenaline pushed me to try even harder. This led to the 2012 sale of Untitled, a portrait of a haloed black man with a flaming red skeleton. This, too, was from that vintage year 1981. Its owner, Robert Lehrman, was a low-key collector in Washington, D.C., a town not known for its embrace of the avant-garde. A lawyer and heir to the Giant Foods supermarket fortune, Lehrman had bought two Basquiats back then for $5,000 apiece.

He had sold one for a normal profit before art became like big game hunting; now was the time for an abnormal profit. The market was euphoric. Was the exuberance irrational? Time will tell, but the exuberance continues to snowball. Having sold in 2008 an interest in Phillips de Pury to the Mercury Group, the leading Russian luxury-goods conglomerate, I was flush enough with oligarch wealth to compete with Christie’s and Sotheby’s and give Mr. Lehrman the guarantee he required. That was the amount he would get even if Untitled sold for below its estimated sales price of between $9 million and $12 million. It was a high-risk strategy, but this was a game of no pain, no gain. I was used to rolling the dice.

Contrary to popular belief that an auction is a roomful of waving paddles and multiple bidders, for Untitled there were only three bidders, and none of them were in our packed auction room in Chelsea. Some auctions are filled with battling bidders, but not this one. This was quality over quantity. Still, there was immense excitement. If the Romans came to the Coliseum to see blood, the New Yorkers came to Phillips to see money. The anonymous collectors were all represented telephonically by Phillips experts, but they were all watching the auction online, and it was my job as auctioneer to make them as desperate to bid, and bid high, as if they were right there below my podium.

Although it may have seemed that in selling to my employees, I was preaching to the choir, in truth I was working as hard as a missionary trying to convert a tribe of headhunters. My gospel was one of transcendent inspiration mixed with eternal value. I knew precisely who the bidders were. I knew who was on those phones. I’d get one bid, and I would look at my experts, beseeching them and their clients to step up, and step high, or else they might lose the treasure. The signs were simple, an arched eyebrow, an extended stare, a change of tone; whatever, the challenge was to deliver the message of a great headmaster with Oscar-worthy finesse: You must do better. It was essential to convey my bullishness. I was high on Basquiat.

Also contrary to popular belief, most of these eight-figure auctions are not drawn-out affairs. Short and sweet, they can last anywhere from one minute to a dozen. This one lasted six minutes. When I banged the gavel and smiled at the phone bank, the price was $16.3 million. The high estimate had been shattered. The record was mine. The crowd breathed a collective “wow”. Loud applause filled the room. It felt great. But I knew it wouldn’t, couldn’t last. And I was glad. That was what made the business so exciting. You could never rest on your laurels. You could never get bored.

The new-record $48 million Dustheads had been sold—over the phone—to a thirtyish Malaysian bon vivant named Taek Jho Low. Nobody knew what he did for a living. Some said oil, some construction, others arms. He was a Wharton grad, and he must have learned something, and learned it well. We were in the Wharton age, when MBA was more likely to be the title of the super-collector than OBE, “von”, or “de”. Inherited wealth was being dwarfed by tech wealth, by oil, by hedge funds. These were where the new players at the auction houses—and at the casinos of the world—were coming from.

The talented Mr. Low was one of the few major collectors I didn’t know. Where had he been keeping himself, I wondered, as I put him on my “to meet” list. I looked around Christie’s auction room. The paneling gave it a much warmer, library-like feel than Sotheby’s clinical white chamber, which was more like an operating room. But wasn’t that what was going on, operating, at the highest level? I knew just about every face in the room, certainly every face connected with a hand that might raise and bid. I had to. In art, knowledge—of the art, and of the buyers—was power, and knowledge meant business. Ignorance could only be measured in misery and failure, never bliss.

Five rows in front of me, right in front below the podium, was Laurence Graff, the poor Stepney-born London diamond merchant who had become the new Harry Winston. Graff had proven to be as astute in art as he had been in jewelry. The two were very closely related, objects of beauty. Tonight his quarry was Roy Lichtenstein’s 1963 Pop riff on Picasso, Woman with Flowered Hat. It was being sold by Revlon’s Ron Perelman, with an estimate of $28 million. I had just had tea with Graff, resplendent in Savile Row bespoke, looking like the king of diamonds that he was. Graff was in New York for the sale with his stunning half-Brazilian, half-English fellow jeweler girlfriend, Josephine Daniel, thirty-plus years his junior and mother of two of his children.

At tea Graff had told me he was fond of Lichtenstein. How fond I would now see, as he went mano a mano with Brett Gorvy, Christie’s young (fiftyish) chairman, who was representing an anonymous phone buyer on the hotline bank beside the podium. Notwithstanding his high office, Gorvy, in contrast to Graff, was soberly and unobtrusively dressed—like a banker, a lawyer, some sort of fiduciary. The idea was that in this service business you should never steal the thunder of your clients. Where Gorvy did dazzle was in his seriousness and dedication. The Graff–Gorvy competition was like a tennis match, round by round, with Graff bidding less with his nearly imperceptible hand gestures than with his eyelids. Up and up it all went, until Graff broke Gorvy with a bid of $55 million, nearly double the estimate.

The gallery swooned. All the top dealers in the world were there, following the action. First and foremost was Larry Gagosian, the unflappable Beverly Hills–Armenian silver fox who had become the Duveen of his generation. If Gagosian was the new Duveen, the Nahmads, Syrian Jews who had empires in both London and New York, were the new Wildensteins. Several Nahmads were in attendance. Conspicuously absent was Hillel “Helly” Nahmad, the thirty-something owner of a distinguished Madison Avenue gallery, envied playboy/serial dater of supermodels, and an art Pied Piper who had turned his Hollywood friends, like Leonardo DiCaprio, on to the joys of contemporary art. Alas, Helly had just been arrested in Los Angeles on charges of involvement in an international high-stakes gambling ring, for which he would ultimately serve several months in jail, after which he returned to art, where he remains at the top of the game. On this night, the family showed up, and Helly was not discussed. The art show must go on.

Then there were the Mugrabis, also Syrian Jews, who had emigrated to Bogotá, where they became fabric merchants and had built their collection by buying up huge lots of paintings whenever the art market crashed. They had the world’s largest trove of Warhols, over eight hundred strong, not to mention more than a hundred Basquiats, plus many important pieces by Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince. They owned giant warehouses in Geneva and in Newark. Saying hello to father Jose, and sons David and Alberto, I mused at how the art market seemed to be dominated by these men with Levantine roots. I guess they shared some kind of genius trading gene. The only one of these gilded Middle Easterners missing tonight was London’s Charles Saatchi, the advertising mogul who became the Iraqi Cosimo Medici of the Young British Artists, as responsible as any collector for the contemporary fiscal fireworks I was witnessing tonight.

Observing the scene from one of Christie’s skyboxes, which are often obscured with semitransparent curtains that protect the identities of Garbo types and Arab princes, was Christie’s big boss, François Pinault, the French tycoon who also controls Gucci, Bottega Veneta, and Stella McCartney, but is most famous to Americans for being the father-in-law of movie star Salma Hayek. Pinault is totally hands-on. At Art Basel, he once disguised himself as a porter wearing workman’s overalls just to get an early look at what would be for sale. Such is Monsieur Pinault’s competitive drive, his passion to win. That I had dared to challenge this giant, backed by his archrival Bernard Arnault (LVMH, plus Dior, DKNY, Marc Jacobs, you name it), in the auction wars of the new century had seemed to many like suicidal madness. Whatever, François waved down a warm hello.

We had seen each other a few nights before at the “kids’ auction”, a charity sale to benefit the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, dedicated to bird and wild-animal sanctuaries around the globe. Save that tiger! While only $31 million was raised, compared to the $500 million tonight would bring, the publicity value was worth the difference if it got young people to follow their beloved stars’ burgeoning interest in art. In addition to Leonardo and Salma, Tobey Maguire, Bradley Cooper, Mark Ruffalo, and Owen Wilson were all in avid, camera-ready attendance. Larry Gagosian showed his appreciation by paying over $7 million for a Mark Grotjahn, winning even more of Young Hollywood’s hearts and minds, as if he needed any, by proving he was “with the program”. Larry is the program.

An auction is only as big as its buyers, and tonight boasted what on the old New York Yankees was known as “Murderers’ Row”. In addition to Graff, there was the Emperor of Los Angeles, Eli Broad, who nearly singlehandedly transformed the movie capital into an art capital, godfathering the city’s main museums and building a classic one (and more) of his own. Eli, now in his eighties, has the energy of a teenager. His fountain of youth is art, which sends him and his wife, Edythe (they’re known as E&E), Gulfstreaming around the world on what has become an infinite loop of glamorous yet serious art events, all of which started with Art Basel, in the city of my birth and own conversion to the religion of art.

I was highly flattered that I had made Eli Broad’s impressive short list of candidates to become the director of LA’s MOCA (Museum of Contemporary Art). When he had interviewed me in 2009 in his South Beach hotel suite at Art Basel Miami, I was preoccupied with my own business of Phillips and passed with regret. I recommended my friend and fellow candidate, the brilliant art dealer and SoHo gallerist Jeffrey Deitch, as the ideal man for the job, and was thrilled that Eli eventually chose him. Jeffrey’s appointment, his turbulent three-year reign at MOCA notwithstanding, was testament to how far outside the box Eli Broad is willing to think, hiring someone far off the conventional curatorial/art-history-academic/nonprofit career track. Jeffrey’s shows at MOCA, such as his “Art in the Streets” graffiti exhibition, were beyond original and reflected the innate originality of his staid-seeming patrons the Broads.

For all their billions, the Broads are as plain as their collection is grand. It’s all on their walls, not on their backs. Talk about insurance salesmen. Trained as an accountant, Eli made one fortune in tract homes, another in insurance, before he got hooked on paintings. It all started with a Toulouse-Lautrec poster and a Braque print that Edythe brought home. She passed on a Warhol soup can, because she thought Eli would shoot her for its $100 price tag. The Broads are living proof that you don’t have to be fancy to be a collector.

The Broads’ opposite number was there as well. Peter Brant, the polo-playing playboy billionaire, published Art in America and Interview. He produced the films Basquiat and Pollock. He had a great new foundation/museum in Connecticut. He genuinely loved art. Befriended by Warhol as a young heir and converted into a patron at an early age, he turned his Bulgarian-born father’s paper company into a vast empire that enabled Brant to pursue his multiple passions of art, horses, and distaff pulchritude. Tonight his oft-embattled wife, Stephanie Seymour, supermodel and Axl Rose ex, who greatly disappointed the tabloids by reuniting with Brant, was not in attendance. But Peter Brant never needed a prop.

Even with the tens of millions changing hands tonight, Peter was setting the stage for a still bigger auction coming up in November by consigning to Christie’s his massive orange Jeff Koons balloon dog sculpture. The estimate was from $35 million to $55 million, which would belittle even tonight’s record Basquiat sale and set a new high for Koons. There were four other Koons balloon dogs, each in a different color, and the owners constituted an oligarchy of their own: Brant, Broad, Pinault, Greek tycoon Dakis Joannou, and hedge-fund overlord Stevie Cohen, whose troubles with the SEC had kept him, just as legal woes had kept Helly Nahmad, off the floor tonight.

Speaking of exclusion, I was still sorting out my emotions regarding my major life change in leaving Phillips de Pury that past December. The Russians at Mercury had bought out all my shares in the company in 2012. Now I was gone. I had changed the once-stuffy auction house into the cutting-edge beacon of contemporary art, and, as was my historical wont, decided to move on to new challenges. But I was gone, and so was my name. When Joseph Stalin eliminated his rivals, they ceased to exist, and were known as “non-people”. So it seemed to go with the new de-Pury-less Phillips. I had given it my best shot, taking on the two giants, and while my David had not slain the double Goliaths, I had certainly shaken their firmament. A non-person I could never be.

Sure, whenever I saw a podium, I wanted to be on it. I witnessed the joy of my friend Tiqui Atencio, who had put the Basquiat Dustheads on the block. Tiqui, an elegant Venezuelan who has the greatest home and gives the wildest parties on the French Riviera (and that’s saying something), is no stranger to exuberance. When the $48 million hammer dropped, she leapt out of her chair and threw both arms high in the air, as if her team had just won the World Cup. I missed sharing that moment of triumph. The call of the gavel was the call of the wild. That’s why I kept my hat in the ring, even minus the auction house, by doing charity auctions around the world, often once a week.

I watched Christie’s Finnish auctioneer, Jussi Pylkkanen (a spelling-bee showstopper), run up the millions. It wasn’t that hard. For someone worth billions, as were so many of these auction-house habitués, raising a bid by a million was play money. Meaningless. There was no pain involved, only the pleasure of high rolling. Again, this was the casino effect. Was the casino rigged? That’s been the cry of reforming legislators in New York for years, trying vainly to outlaw the so-called chandelier bids, in which the auctioneer raises the ante by pointing to a vague rich someone in the back of the room. That someone could be a chandelier. That someone doesn’t exist. It’s within the auctioneer’s discretion to make up bids throughout a sale, just to keep a slow auction rolling, up to whatever confidential minimum reserve price has been agreed upon by the seller and the auction house. By the way, it’s all completely legal and is likely to remain so.

Remembering the eighties, when a million dollars would create a huge sensation, I watched these big bidders spread around the room. Christie’s knew better than to seat two rivals anywhere near each other. The seating chart at these auctions was just as fraught as those at the “power” art-crowd restaurants, from La Grenouille in New York to Harry’s Bar in London to the Kronenhalle in Zurich to the China Club in Hong Kong. I figured that there were 25 to 35 people in the world capable of spending, and prepared to spend, over $100 million on a single piece of art. Another 100 to 125 could, and might, spend $50 million. The pyramid got increasingly wide from there. Works selling for $1 million, once front-page news, are never even mentioned now. At the base of the pyramid is eBay, with, at last count, 85 million collectors bidding and buying in what is the world’s largest flea market. Of those 150 or so highest rollers, all of them seemed to be here, in body or spirit, tonight.

I thought how I’d do this auction, how I might get even bigger numbers—you know, the nobody-does-it-better syndrome that is an occupational hazard of the auctioneer. Big art demands big egos. But as much as I hate to confess it, I had to admit to myself that Jussi was doing an amazing job. In all honesty, what I wasn’t feeling was seller’s remorse, or auction envy. My biggest emotion was extreme exhilaration, the thrill of an exploding market that I was figuring out how to reposition myself in. Contemporary art had become the Gold Rush of the millennium, and I was one prospector who could never be deterred from the thrill of the chase and the endless eureka moments that came with it.

3

ARTOPOLIS

As an art dealer, an art collector, an art obsessive, I would like to think, without being overly chauvinistic, that someone as mad for art as I am could have only come from one place. That place is Basel. A lot of cities in the world have great art—Florence, Paris, St. Petersburg come quickly to mind—but in no other city does art flow in the veins of its citizens as it does in my Swiss home. Today, you say the word “art”, and the first urban free association is Art Basel, whether it’s taking place in Basel itself or in Miami, Hong Kong, or wherever else the world’s preeminent art fair may be cloned in the future. Say “Basel”, and you think Art Basel; say “art”, and you think Art Basel. But Art Basel is a very new phenomenon, dating back only to 1970, while art in Basel has been going on for centuries in this little, perfect city on the Rhine, where France, Germany, and Switzerland all meet. Basel is the perfect intersection of culture and wealth, a fertile crescent of art collectors.

Basel is home to Switzerland’s oldest and finest university, the Harvard of the Rhine, where Erasmus and Nietzsche both taught. The University of Basel goes back to 1460. Deeply connected to it is the Kunstmuseum, which goes back to 1661 and is the world’s oldest public-access art museum. And then there are the pharmaceutical companies; that’s where the big money is, and that’s where collections get started. Novartis, Hoffmann–La Roche, Syngenta, and many others are all right here. Put simply, the chemistry here is literally perfect for great art collections to form. There’s a basic art instinct in that Rhine water, and the Swiss business gene has created the ways and means to harness money to culture and build something beautiful. Those are my roots.

I was born in Basel in 1951. My father was a lawyer there for Hoffmann–La Roche. His family was from Neuchâtel, that picturesque castle town a hundred kilometers from Basel. My father was a baron, though that was a title he kept in the closet. (Just for the record, I’m one, too, and I keep my title in the closet as well. Self-effacement runs in the family.) Our ancestors had been governors of Neuchâtel for centuries and had been ennobled by Frederick the Great of Prussia, in effect for their role in keeping Frederick’s Protestant faith vis-à-vis the Catholic one of France. Because of its proximity to these frequently warring powers, Neuchâtel was something of a political football. Having enough of this game of nations, my ancestor David de Pury left the scene altogether and moved to Lisbon, where he became banker to the King of Portugal. However, when he died, he left his Portuguese fortune to Neuchâtel; hence his statue in Neuchâtel’s main square, Place de Pury, and hence my royal welcome when I wed my first wife in the castle that is the emblem of the city.

I do have ties to America. In 1731 David de Pury’s son Jean-Pierre petitioned the English king to establish a settlement of six hundred Neuchâtel peasants, in search of a better life, on the swampy banks of the Savannah River south of Charleston, South Carolina, then the Paris of the New World. The de Pury colonists sailed from Genoa. Adding an extra “r” for good measure, they called the town they founded Purrysburg. Alas, despite the Protestant work ethic of the settlers, malaria and other diseases of the Low Country, as that area is known, rendered Purrysburg a ghost town not long after the American Revolution, though not before George Washington put the town on the map by having breakfast there. They couldn’t brag that “George Washington slept here”, which is the ultimate American validation, like “By Appointment to Her Majesty”. But it was close.

The lost colony provided ever-historic-minded South Carolina with a host of Swiss names that became entrenched in that state’s founding Huguenot (French Protestant) aristocracy. In the 1980s, a Neuchâtel-Purrysburg exchange was initiated by descendants of these South Carolina grandees, and I was invited to help commemorate Purrysburg’s 250th anniversary. The celebration of this gone-with-the-wind settlement was so romantically nostalgic that I couldn’t help feel a little like a Swiss Rhett Butler.

As a boy in Basel, however, I felt more like a Swiss Oliver Twist. When I was ten, I became a drug orphan. That wasn’t as grave as it sounds. But I was indeed cut adrift when my father was given the career opportunity of his lifetime, to transfer to Tokyo and run the Hoffman–La Roche business there. What was a small ten-man operation when my father arrived in 1961 grew under his leadership to a giant corporation employing over ten thousand people. My three siblings, two brothers and a sister, were all older than I, and on their own. I had to be sacrificed on the altar of my father’s brilliant career and was placed with family friends.

I had been a terrible student in the famous Humanistisches Gymnasium that had been founded by Erasmus. Despite being tall, I was awkward and awful at sports, always the last to be chosen. I still loved soccer, if only vicariously. I loved art even more, which amazed my parents, and doubly amazed my “step-family”, the Bonhotes, headed by an executive from Father’s pharmaceutical rival Ciba-Geigy. The Bonhotes were as acultural as my parents had been culture vultures. Once when Mrs. Bonhote asked me where I had been that afternoon and I told her I had gone to a Klee exhibition, she thought I had gone to look at a show of keys. Key in French is clef, pronounced Klee. Maybe Mrs. Bonhote thought I had a future as a locksmith. She was living proof that while Basel was a great art town, not everyone there was bitten by the art bug.

My personal infection had started on childhood trips with my mother to Florence, where I had been transfixed by the Uffizi and the Bargello even more than by the gelati that had been the reward for most normal kids for putting up with the art. Adding fuel to the fire was my first trip to Paris, staying with an uncle on Île Saint-Louis and being unleashed at the Louvre. Maybe if Euro Disney had been around, I might have been distracted into a totally different life path, but it wasn’t, nor were Disney’s Davy Crockett episodes available on European television. We were stuck with Old World culture, and insulated from the small-screen pop-culture seductions of the New.

So art was my “thing”. I adored school excursions to the Basel Kunstmuseum the way others would adore going to movies. The father of one of my friends had inherited part of the art collection of Basel’s first great collector, Raoul La Roche. My friend’s house was completely banal, but the art was heavenly. I would be transfixed by the Picassos, the Legers, the Braques, the Grises, the way my friend, who was indifferent to his father’s art, would devour comic books.

Eventually, I went with this friend to Paris, a four-hour train ride from Basel, to visit the amazing modern house designed for La Roche, who was not one of the drug La Roches but a banking La Roche, by his best friend, Le Corbusier, which housed most of his collection after he died in 1965. La Roche, who began collecting the modern art of his Parisian friends in 1918, when he was only twenty-nine, became a role model for my young self, something unusual to aspire to. My older brothers, both brilliant students, were stars at a young age. One was a theologian, the other a lawyer. I had no hope of competing with them. So I looked for another path, a road not taken.

During my lonely adolescence, an event occurred in Basel that illuminated why, when it came to art, this town was different from all other towns. The year was 1967. I was sixteen, deep into my obsession with Anglo-American pop music. I liked American Pop Art as well. One of my art buddies had an American mother. She introduced me to Rauschenberg and Warhol, who I thought were cool and captured the essence of an America that existed in my dreams and in my ears. Andy Warhol created one image, Jimi Hendrix another. Marilyn, Elvis, Campbell’s Soup, “Purple Haze”. I later learned that American boys of my generation escaped the confines of their lives by reading National Geographic. I escaped mine with art and music. While the idea of becoming the next Raoul La Roche was beyond adolescent fantasy, I collected my Beatles, Stones, Beach Boys, and Bob Dylan albums the way my friends’ families would collect their art.

No family in Zurich had better art than that of my school friend Ruedi Staechelin. Ruedi’s grandfather, Rudolf, had one of the world’s preeminent collections of French Impressionists (Monet, Renoir, Sisley) and Post-Impressionists (Van Gogh, Gauguin). Ruedi himself would also go on to work at Sotheby’s. In April 1967, a disaster befell the Staechelin family. They were the owners of Switzerland’s biggest charter airline, Globe Air. One of their planes, a Bristol Britannia en route from Bangkok to Basel, crashed in a thunderstorm near Nicosia, Cyprus, killing 126 mostly Swiss vacationers. Both pilots had violated the limits on hours, and one of them had insufficient training on the aircraft. The Staechelin family was being sued to death. They didn’t have enough insurance to pay the victims. The only way they could survive their financial crisis was to start selling their art. This was my first exposure to fiscal dire straits. Money troubles for rich Swiss were a rarity in a country as famous for its banks as for its cheese and watches.

First the Staechelins sold a Van Gogh to Walter Annenberg, just before he became Nixon’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. But one Van Gogh would not a legal firestorm quell. They had to sell more, and Annenberg was the Qatari of his day, an insatiable collector with pockets as deep as the Mindanao Trench. Next on the block were two of the world’s most valuable Picassos, then on permanent loan to the Basel Kunstmuseum. Both were masterpieces: 1906’s Pink Period Two Brothers and 1923’s The Seated Harlequin. When word got out about the Annenberg acquisition, the people of Basel went up in arms—and not only because Annenberg was an American, and a nouveau riche American whose own father had gone to prison and made his fortune not printing Gutenberg Bibles but peddling The Racing Form, the bible of horse racing and betting.