9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

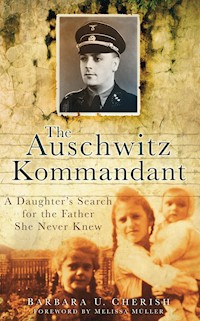

Barbara Cherish's upbringing in Nazi-occupied Poland was one of relative wealth and comfort. But her father's senior position in the Nazi Party meant that she and her brothers and sisters lived on a knife edge. In 1943 he became commandant of perhaps the most infamous of all the concentration camps: Auschwitz. The author tells her father's story with clarity and without judgement, detailing his relationship with his family and his unceasing love for his mistress, as well as the very separate life he led as a senior officer of the SS. Captured by the US Army at the end of the war, he was held at Dachau and Nuremberg before being extradited to Poland. He was tried in the 'Auschwitz Trial' at Krakow, found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and executed in January 1948. A unique insider's view of the dark heart of the Third Reich, it is also a heartbreaking tale of a family torn apart that will open the eyes of even the most well-read historian.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Dedicated especiallyin loving memory tomy father, Arthur Wilhelm Liebehenscheland my mother, Gertrud Baum Liebehenschel,with love and gratitude for the gift of lifefrom one of ‘The Other Children.’

‘History is in the mind of the teller,

Truth is in the telling …’

Contents

Foreword by Melissa Müller

Preface

Prologue The Photograph

Chapter One Party Member # 932766 & Family Man

Chapter Two Oranienburg

Chapter Three The Last Embrace

Chapter Four Auschwitz

Chapter Five Austria

Chapter Six One Son Captured, Another Born

Chapter Seven Betrayed and Banished as Refugees

Chapter Eight Berchtesgaden

Chapter Nine Leaving ‘The Other Child’ Behind

Chapter Ten Journals of a Prisoner

Chapter Eleven The Trial

Chapter Twelve A New Family, A New Identity

Epilogue The Journey Home

The Journey Continues

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Copyright

Plates

Foreword

Growing up without a father is a burden. If the memory of a father is reduced to a single photograph a child is forced to hide, even deny, this is too much for them to carry. The photograph that Barbara Cherish has kept closely guarded since childhood shows a seemingly cultivated man with a mild gaze, wearing the uniform of the SS. A relic of a time supposedly past, but yet still carefully concealed, it depicts Arthur Liebehenschel, appointed by the National Socialist regime, made commander at Auschwitz during the winter of 1943–44, transferred to Majdanek, and executed in Poland in January 1948 as a war criminal.

Out of grief, yet with shame, and with a longing that never faded but hurt more each year, Barbara follows the trail of her missing father. Years of searching through archives and talks with members of the family and contemporaries allowed her to discover important, so far unknown facts, and to listen to the opinions of others, as well as her father’s own words, his letters and diaries, his official correspondence, his hearings and statutory declarations.

Thus we are confronted with a human tragedy that forces us to think carefully before forming a judgement. The simple categories of good and evil do not necessarily fit when we consider Arthur Liebehenschel, just as they may not always apply to the many others who chose to believe in National Socialism initially, but yet still remained faithful and obedient, once the regime no longer hid its criminal intentions. It is always possible that her father questioned the system. He may have suffered more and more, but yet still followed orders with the inevitable consequence of being found guilty. Did he have a choice? Is there a time at which the father of a family could have turned to follow his conscience rather than his desire to provide security? The tribunal in Krakow pronounced their judgement. His daughter does not presume to do so again. We readers should be open to Barbara Cherish’s nuances, and show appreciation for her life experiences, her courage, her frankness, her love.

Melissa Müller is the author of Until the Final Hour: Hitler’s Secretary tells her Life and Anne Frank: the Biography.

Preface

Soon you will be at an age where one looks at everything through clear and different eyes. Do this and judge in peace and fairness for yourself, when in a distant time you are moved toward that direction …

from a letter written by my father, Arthur Liebehenschel,as he awaited trial on charges of war crimes in Dachau, 1945

Last night I dreamed of Papa again … can’t really say ‘again’ as I only remember one other dream of him.

He looked like he does in the favorite photograph I have of him. Early forties, handsome, with smooth black hair wearing his uniform. But in my dream he was thinner, his stature seemed smaller and his gentle and somewhat humble appearance was enveloped in an aura of defeat. I felt his loneliness.

He had been released from prison, found ‘not guilty’, and had been searching to find me and my sister Brigitte. We were at some kind of small airport making reservations to go home. He talked with us in a quiet manner but it seemed to me he didn’t know that I was his daughter. Through our conversation he was beginning to realize who I was. I pulled him over to the side and asked if he knew who I was and if he liked who I had grown up to be? He answered yes, and that he felt very drawn to me and he thought I was pretty. Then he affectionately embraced me. We joked and he was even laughing – not serious as he appears in all of his photos.

Brigitte and I convinced him to come home with us and he picked up his small worn duffel bag, which was the extent of his belongings. I kept thinking to myself, ‘I finally found him but I must be dreaming!’ … only to awaken and find that I was.

Prologue

The Photograph

It must have been his photograph which triggered the dreams that would eventually follow years later.

One afternoon remains so vivid in my memory that I can close my eyes and revisit the experience. I was still in my twenties and I’d hidden his picture at the bottom of my dresser drawer. It had always been my secret, the photo and what it represented. Studying his picture wasn’t unusual for me, but for some reason, that particular moment stands out, although it was one of so many.

Holding his picture, wishing to reach through to the image and touch his face, I gazed at the soft dark eyes looking off dreamily into the distance. They conveyed such a thoughtful sadness. As I studied his features, familiar yet not so familiar, I longed to hear his voice. Was it stern yet kind? I felt the old yearning along with that sense of being lost.

I desperately wanted to reach back in time and draw him out of the photograph and back into my life. He had been part of my life for such a short time. But there was also something dark, even evil in the photo that always haunted me.

I heard footsteps in the outside hallway and hurriedly, guiltily replaced the beloved photo beneath my clothes in the dresser.

It may have been that same night when I had one of the few dreams I’ve had of him: two arms extended through the heavens. Long black gloves covered the hands. They were reaching for me and I felt a paralyzing, terrifying evil power that wanted to pull me to the other side. I tried to avoid them, but couldn’t resist their strength. The black gloves portrayed his dark side, but the instant our hands touched, I sensed an overwhelming force of love and peace and I believe he was communicating with me.

Once, long ago, I was instructed to forget his name and everything about him, denying any connection between us. The more I thought about him, the more questions I had. If I could just step into his photograph and look around, trying to fathom reasons why he rose to the top, why he was ever associated and had volunteered to join such a sinister organization? He became a major part of Hitler’s human machinery, and this in itself both horrified and fascinated me. It was the source of my greatest shame.

But the secrets of our lives, those we find most significant, don’t allow us much respite. They keep rising to the surface until we acknowledge them. He was my secret, the most disturbing factor of my hidden past, the cause of my quest, but he was also the focus of my search for the truth about myself.

I vividly remember that night so long ago. I was already asleep when my oldest sister Brigitte gently woke me and gave me the photo, pressing it secretly into my hand whispering her emotional farewell, ‘I will always love you. Don’t ever forget us.’

It was early December 1956 and I was thirteen years old, accompanied by my recently adoptive parents and a three-year-old brother, facing a whole new future. With my biological mother hospitalized, and without my father’s presence, I had been placed as a foster child with the Poune family who decided to adopt me after three years.

We left Nuremberg for the seaport of Bremerhafen, traveling by train arriving several days later. I always loved riding on trains and it was thrilling to actually experience the encounters of the sleeper and dining cars. Courteous porters wearing tight-fitting dark blue uniforms with round pillbox-type caps were eager to assist us. Crisp white linen tablecloths decked the dining car just like the trains portrayed in my favorite old black and white films.

When we first reached the seaport of Bremerhafen where the USNS Henry Gibbins was docked, the ship appeared ominous through the misty gray fog and cold rain – almost threatening, like an enemy warship. I recall the fascination because never before had I been this close to such a vessel.

We boarded the army transport ship, our floating home for the next two weeks, cautiously walking up the long gangplank hauling our carry-on luggage, wondering how many people before us had done the same. Launched in 1942, she had seen service in the European Theater during the Second World War, and under an order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 she carried 1,000 Jewish refugees from Italy to New York.

After the war, the Gibbins transported war brides from Europe to the United States. Later she was renamed The Empire State IV serving as a training ship for the New York Maritime College. However, this December 1956 she was once again returning servicemen and their families to the United States.

It was foggy and raining as we set sail, waving farewell to the people on the dock while an American military band played The Stars and Stripes Forever. Despite the weather, the scene was breathtaking. But as we pulled out of the harbor I was torn by clashing emotions that overwhelmed and confused me. I felt optimistic excitement about the new country I was headed for, but also there was sad hesitation about allowing myself to feel excited and happy. I was leaving behind my entire past, everything and everyone I had ever known, abandoning the child I had once been.

Like many others in my circumstances, I had already lived a lifetime of upheaval and hardship. I realized I would never see my biological family again, and in my mind I replayed the bittersweet scenes of my mother, my two older sisters with me, and all we had lived through together. I found myself yearning for the mother I had to leave behind, but foremost remained the many unanswered questions surrounding the mystery about the father I never knew. As any 13-year-old I didn’t dwell on these thoughts and soon they were forgotten, although only temporarily. Through the romantic eyes of this young girl I was about to experience a true life adventure on the high seas.

Being a military ship, it was far from what one could call a cruise. However, captured through my own far-fetched schoolgirl imagination, the Gibbins became a beautiful sailing ship and surely the captain had to be a handsome swashbuckling pirate. Somehow that fantasy was rudely shattered early each morning when we were awakened by the loud gong of the reveille, and a deep voice could be heard shouting throughout the ship’s corridors: ‘Reveille and it’s time to get up!’ Each morning I grabbed my pillow and covered my ears, but soon it became a familiar routine and if we wanted breakfast we had to jump up and get to the dining room. There, our waiter named George greeted us at our assigned table with a friendly smile as he served the delicious food prepared in the ship’s galley.

Every day was a new adventure for me. We children on board even decorated a Christmas tree in the lounge. I was wearing my favorite aqua and white striped knit top with a hood when I went off exploring the corridors by myself, but soon realized I had ventured too far when I stumbled upon a large group of sailors. A little frightened, I hurried back to our cabin as one of them called after me, ‘In a few years you’re going to be a beautiful young lady!’ In the tiny bathroom of our modest stateroom I looked at my reflection in the mirror wondering what it was he saw?

The sea was furiously turbulent throughout our voyage as we hit one fierce storm after another. The tremendous force of the huge swells battered the ship so severely that part of the massive bridge section was torn off. I heard rumors that this was the Gibbins’ last ocean voyage because she was not seaworthy to make another Atlantic crossing. However, she would continue to operate as a transport ship until 1959.

We were tossed up and down relentlessly by the waves and it seemed we would be swallowed up into the deep. At such times it was difficult to walk around and we were not allowed on deck. I never became seasick but my new Mom spent a great deal of the voyage in her bunk unable to eat, while my new little brother was extremely seasick hooked up to IVs in the infirmary.

We safely weathered these storms, but the rough seas made it a much longer voyage than anticipated. Everyone on board was hoping we would arrive in New York before Christmas.

Finally, on 21 December, the USNS Henry Gibbins, who had once again bound across the briny deep, entered the port of New York and I became initiated into the Royal Order of Atlantic Voyageurs. We children received a colorful document pictured with sea serpents and mermaids, proclaiming our official Atlantic voyage, signed by the guardians of the deep, King Neptune and Davy Jones.

On deck, in awesome absolute stillness, we all caught sight of the magnificent Statue of Liberty, an unforgettable experience sensed with unusual pride by me, even at the age of thirteen. Historic Ellis Island, called The Gateway to America, which millions of immigrants had passed through, had closed its doors only two years prior to our entry. We had to wait for a few hours to come into port while the Queen Mary, who had priority to dock, processed her passengers to disembark. Finally, we were allowed to leave our ship and immediately entered the large nearby immigration building.

I clearly recall waiting anxiously in several different lines with my new parents going through all of the customary immigration procedures. My new Dad and brother being American citizens were processed through quickly. My Mom and I were detained by customs and patiently went through their routine of bureaucratic red tape. Ursula looked pale and much thinner than when we first boarded, still not feeling too well, and I sensed she was nervous, keeping her red sweater jacket wrapped securely around her. I was holding on to my adorable little blond-headed brother’s hand, still weak, looking bewildered and shy, yet his chubby little cheeks gave way to a faint smile as he looked up at his big sister for assurance. For some reason I was focusing on his polished little white oxford shoes, thinking he too must feel insecure sensing our apprehension. Still in the line for immigrants I nervously clutched my German passport, yet feeling like an American. I was wearing my favorite blue jeans with the turned-up cuffs that were lined with red flannel plaid material with matching plaid shirt, white Bobbie sox and brown-and-white saddle shoes.

But it was especially alarming and I was terribly fearful when the inspection official asked to look through my small, brown leather suitcase. I nodded, but my trembling hands were perspiring. With a great sense of relief, I observed that he barely glanced through the contents.

Had he looked further toward the bottom, under the layers of clothing, he might have found an old album in which I had hidden that very special photograph my sister Brigitte had given to me weeks earlier. The old photo was of my father, and the unmistakable design of his particular uniform carried staggering implications about the officer whose identity I would not be willing to reveal for years to come. The photo surely would have divulged my background and I feared that I might end up rejected, or even worse, sent back – deported – by myself.

After long hours of anxiously waiting, and with my greatest fears laid to rest, my new family and I passed the final inspection. The process was complete and we were allowed to enter New York City. The skyline loomed in the distance, those tall buildings including the Empire State Building, which I had heard so much about.

The first and lasting impression I had as that young girl in my new country remains clearly defined in my memory. I was filled with intense excitement, everything seemed so vast and overwhelming, yet it also felt safe as though I had always belonged there.

Another part of me – the part I would try so hard to silence – was confused and sad. From here on out there would always prevail a secret, inexplicable longing for those kindred souls I had left behind, and they would have to remain mere ghosts from my secret past.

It was cold and already late afternoon by the time we took off on the New York turnpike. As we drove toward our final destination in upstate New York, my eyes followed the road with great curiosity, as around each turn I imagined a whole new life beginning to unravel. Without any warning it started to snow and with a sudden shiver of excitement I remembered that it was almost Christmas – my first Christmas in America!

I was the youngest daughter of Arthur Liebehenschel, one of his ‘other children’. It was a term he had given those of us who were from his first marriage. From my adoption at age thirteen, I had to cast off my old identity and found myself living a life of secrecy. I now had a new identity to hide the shame of my father’s name, and it was only the beginning for a child who had no preconceived idea of what it would be like having to live a life of secrets and lies, shrouding the truth of her past.

That December of 1956, as I came to America from Germany, I was leaving behind that child, who during her brief existence had already lived a whole lifetime of human experiences. I left behind a childhood in foster homes and my biological family, with the lingering grief over my mother’s hospitalization in a mental institution. I also resigned myself to bury the many unanswered questions concerning my absent father.

I learned at an early age that I must please in order to belong, so I knew it was necessary to shed the first thirteen years of my life, erasing that part of my identity as if I had somehow died or never existed. This began the secretive cover-up, the inner turmoil that would become part of my everyday life, and the mystery that surrounded the family I had been born into.

As an adult, I spoke English without an accent. I became an expert at personal subterfuge. I hid the facts of my life, deftly evading questions and always covering up the truth. My two children knew very little about my past.

But I lived with an inexplicable sadness and longing to know who I really was. I carried this burden silently within me, and it would be four decades before the child I had left abandoned on the shore of that distant continent would eventually reappear and search for her true identity.

I’ve heard that it often takes a crisis to make us look deeply within ourselves, to face what we find with total honesty. It took the death of my older sister Brigitte, diagnosed with breast cancer, and the end of my twenty-eight-year marriage, to finally thrust me into the mirror. I had to understand myself, to achieve that self-knowledge that begins the path of growth and discovery. This quest had to begin with knowing my father, for it was he who had fostered the shame that had lead me into hiding.

My sister Brigitte, after a year of chemotherapy and radiation, preceded by a radical mastectomy, was told that the cancer had gone into remission. But seven years later, the cancer returned even more virulently than before.

At the same time, I watched helplessly as my husband sank deeper and deeper into an alcoholic haze. Gone was the handsome, responsible man I had loved and married. In his place was a distant stranger. Adept at concealing ugly truths from years of practice, I kept my two children from knowing just how serious their father’s drinking problem actually was. I retreated into devoting my time caring for Brigitte. I watched in despair as my sister, who had been the strongest one in the family, grew weaker and smaller and more dependent.

She didn’t know it, but we each – for different reasons – were helpless during that painful time. I felt as though everything was crumbling around me. A sick feeling in my stomach constantly plagued me, reminding me that this was not a bad dream. This was reality.

On the afternoon of 30 December 1988, two days after her fifty-sixth birthday, I left Brigitte sleeping and kissed her goodbye about 3 p.m. At 9:30 that evening, her husband Heinz called to tell us she was gone.

On a beautiful crisp day in January 1989, I stood on a boat that would take Brigitte’s ashes to their final destination. Thirty-two years earlier my first ocean voyage had taken me far away from my beloved oldest sister. Once again I found myself on a ship taken out to sea, but this time to say my final farewell to Brigitte. I looked out over the ocean as the water displayed blues of every hue while a biting wind pierced through me.

As the relentless waves tossed the boat up and down, the shoreline vanished and reappeared with an almost hypnotic rhythm, lulling me into memories of Brigitte: as a beautiful sixteen-year-old with gleaming black hair, pirouetting across the dance floor at the Eva Weigand Ballet School; as the determined young woman who courageously rescued me when I was a starving child; as a vivacious woman sitting with me on the beach at Sea Cliff not far from here, sipping champagne with strawberries as we watched the sun sink beneath the horizon.

Heinz and their son Kye cast Brigitte’s ashes along with some rose petals over the side of the boat. I watched the trail they left until they were carried away by the waves, quickly disappearing, leaving nothing but the reflection of the early afternoon sun bouncing off the blue water. Suddenly I felt terribly alone.

A frightening realization suddenly gripped me. I could no longer hide in the shadows, feeling safe and secure behind Brigitte’s urgent need for me. I had to face what was left of my own life.

I would make one final effort to save my marriage, but to no avail. It was the second loss in a very short time. Our divorce was final in March of 1991. Twenty-eight years together, and now my husband and I parted, each leaving the Ventura courthouse in tears to go our separate ways.

I can still hear his last words to me when I moved out of our new home on Riviera Court. As I walked out into the snow and climbed into the moving van he called out to me, ‘Have a nice life!’ But divorce is death. I’ll never really get over it.

Now, at age forty-seven, I began my self-search with the photograph. As I reached for it I heard – or rather felt – a voice deep inside of me command: ‘This is a part of who you are. You must get it back.’ It wasn’t my own voice, but rather one with authority and conviction, a voice in touch with the deepest part of my soul. I had never heard this voice, but it wouldn’t be the last time it spoke to me. Perhaps it came to me at that moment because for the first time in my life no one could control me or force me to deny who I really was.

I looked at the picture in my hand, fragile from years of secretly grasping it, and an overwhelming need to protect it propelled me into action. I rummaged through other pictures I had, searching for a frame, something that would give his photo the importance I thought it deserved. At that moment I wondered about the significance of ships in my life because I chose a silver frame which held a sketch of a sailing ship.

I again studied his soft eyes and gentle expression. What was he looking at as he gazed intently into the distance? Like all photos of soldiers, the image projected strength and pride in the uniform. But this was not just any uniform. If you looked closely, you would see the forbidding death’s-head insignia of a German SS officer. It was this insignia and what it stood for that had been the evil haunting me for so long.

The SS officer in the photograph was my father, one of Hitler’s elite, Arthur Liebehenschel, Second Kommandant of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp during the Second World War.

And so it was, that the special photo which my sister Brigitte gave to me when I was just thirteen before coming to America – the photo of the handsome man whose features resembled mine – the Nazi officer wearing the black uniform – the same photo I would keep secretly hidden and wouldn’t share with anyone all these years was, as Brigitte told me, my Papa.

Whenever I took the photo out of my dresser, gazing at his face, tracing his features with my fingers, I saw in his eyes my own eyes, in his nose, my nose. What permitted him to rise to the top of such a loathsome organization? Was there something so dark and sinister inside him that could also exist within me as well? If so, I had never known it. Wouldn’t any child of an SS officer ask the same questions?

His photo reassured me that I had once belonged to a family who bore a resemblance to me. It was my only tangible evidence that I had actually had a father. He left my mother, my siblings and me when I was only nine months old, as he was deeply in love with another woman. Life’s lessons and maturity allowed me to forgive him for that. When I looked at his photo, I didn’t see the officer, but the man – I didn’t see the Kommandant, but my father.

The near collision of the two events which tore my life apart – Brigitte’s death and my divorce – compelled me to acknowledge that I had no personal history to rely on. It was time to get to know my father and thereby know myself. Though I never actually knew him, he has shaped my life profoundly.

My search was never with the intention of exonerating him.

Chapter One

Party Member # 932766 & Family Man

I remembered that Brigitte had recorded some audiotapes of our family’s history shortly before she died. Until now, I had had no desire to listen to them, not wanting to revive the pain of losing her. But now I was ready.

I had married young, at age nineteen, and since my twenty-eight-year marriage had come to an end, I found myself alone for the first time in my life. At my small apartment I picked up the telephone, and with a trembling hand dialed the number of Brigitte’s son, Kye. Without telling him the reason for my request, I asked him for the tapes. He readily agreed to make me copies. I hung up the phone and immediately felt that I had made an important decision.

Because I had no plan beyond listening to the tapes, I had no way of knowing that I had just taken the first and easiest step in what would be an eight-year quest before I would eventually find some of the answers I sought. This journey would be filled with frustration, disappointment, emotional turmoil, conflict and countless dead ends.

It was later that year in 1991, on a hot, sunny afternoon, that the search for my father actually began. With a mixture of excitement and trepidation, I sat down alone to once again listen to Brigitte’s melancholy voice as she spilled out her recollections of our family’s history of which I’d known only the most rudimentary of facts. She brought into sharp focus some memories that had grown faint throughout the years, but mostly she revealed details about my family that I’d never heard before.

I took notes as I listened to the tapes, writing on a large yellow note pad with a pencil that would soon be worn down to a short stub. And then it was not until some time later that I finally retired the old typewriter and replaced it with a computer.

My father was born on 25 November 1901 as the illegitimate son of Emma Ottilie Liebehenschel and Anton Heinrich Weinert in Posen, Poland. It was not unusual for these ethnic Germans, known as ‘Reichs-Germans’, to live in Poland. His mother named him Arthur Wilhelm Liebehenschel because Anton was already a married man and denied paternal responsibility, even refusing to give him his name.

Anton, a teacher as well as a railroad official, soon deserted them, leaving Emma to raise her only son by herself. Arthur held a deep, loving bond with his mother, who worked hard as a seamstress in order to survive. His adoration for his mother often was expressed throughout his writings. As a seamstress, she worked diligently to keep her child, but barely making ends meet.

There never was any mention or evidence of his own father, and one senses through this a deeply hidden void, creating more hurt than resentment. His father abandoned him before he was even born and never acknowledged him as his son, even in later years.

In Arthur’s journals, he spoke of a stepsister Helene whom he wished he could have met, but never knew. Little is known about his actual childhood but he mentioned several times in his journals that it was a difficult one and the good memories were those of his beloved mother.

The First World War had ended with Germany defeated in August 1918 and disarmed by the Treaty of Versailles. That was under the Weimar Republic, in power from 1919–1933, which tried to establish a democratic parliamentary regime. From testimony given by my father on 7 May 1947, he stated:

My mother came from a family of Inn Keepers from East Germany and my father was a Railroad Official, a low ranking civil servant working as Secretary of the Railroad in Posen, Poland. He was a teacher by profession. His background stemmed from a line of mill workers in Prussian Silesia. I was raised in a religious atmosphere. My father was Catholic but I was raised solely by my mother who was a devout Protestant.

I have fond memories as a child of our neighbors, the Polish family known as Glowinski to whom I owed much in that time. Their family consisting of ten children was very prosperous and life was much easier for them than for my mother and me. I spent a great deal of time with these people and was often given generous gifts.

I was an only child. My father lived to be seventy-four and my mother died at age fifty-one. I had been a member of the Lutheran Church.1

After finishing high school Arthur studied public administration and economics. As a young man he joined the ‘Freikorps’ (Free Corps) where he served as a ‘Border Guard-East’ from January 1919 to August of that same year. This newly formed illegal military authority came into power after the defeat of the First World War, consisting mostly of idealistic activists who had been members of the armed forces; many of these men later also became members of the Nazi Party. It was brought into being by those who were of Hitler’s generation who shared his enthusiasm to defend Germany from the Bolsheviks.

In October 1919 Arthur joined the army – the Reichswehr – at age eighteen. It was known as the ‘100,000 Men Army’ as this was the maximum number allowed after the First World War. The military seemed to offer some measure of security as well as the chance for a patriotic young man to serve his country.

In 1920 the National Socialist German Workers Party, known as the ‘Nazi Party’, derived from ‘Nazional’, had a mere sixty members. Adolf Hitler was the head of this new political party, the NSDAP. He promised, among other things, to return Germany’s colonies to her, which had been lost at the time of defeat. War reconstruction and payments to the Allies were among the great economic pressures. With the country in such turmoil and politically unstable, Adolf Hitler became the dominant figure. His hypnotic speeches had an extraordinary effect on the people.

In the Reichswehr my father was in the Infantry for two and a half years and then became Master Field Sergeant in the Medical Corps. His rank in this army was ‘Sanitaets Oberfeld-Webel’ at the time of his marriage to my mother, Gertrud Baum, on 3 December 1927 in Frankfurt-Oder.

I unfortunately have little information about my mother’s background or childhood. Hers, too, was not an easy life – the sadness reflects in all of the photographs which I have of her. She was born in Zuellichau, Poland on 3 October 1903, a small pretty woman with hazel eyes. My parents, both ethnic Germans, met when she was working as a secretary for a college professor in Zuellichau. Evidently she worked closely for a number of years with a Dr Rudolf Hanov, the author of a book on the history of a local students’ group. It was published in 1933 and he dedicated this book to her:

Dedicated to Frau Gertrud Liebehenschel, the former Gertrud Baum, for her longstanding loyal assistance. In fond memory of our collaboration toward matters concerning the subject of Burgkellerei – by Dr. Rudolf Hanov.

My sisters remembered that our mother often spoke highly of this old friend and wondered if they had been romantically involved at an earlier time.

Still living in Frankfurt-Oder on the Polish border, my parents’ first child – my oldest brother Dieter – was born to them on 2 September 1928. At the time, my father had also been attending secret underground meetings and became very involved with the Nazi movement. As with so many other people, he was overwhelmed by the powerful speeches of promises to reunite Germany and to return the people’s dignity and economic welfare.

By the end of 1929 unemployment had risen to three million, and inflation was rising making circumstances even more favorable for Hitler and his party. On 30 January 1933 the forty-three-year-old painter from Austria was appointed Chancellor of Germany.

After twelve years of duty in the Reichswehr, father was discharged as Master Sergeant, a non-commissioned officer, on 3 October 1931. Throughout the following months after his discharge he remained unemployed. In 1932 my father went to work for the Finance Office in Frankfurt-Oder.

After my brother Dieter was born, Brigitte arrived four years later on 28 December 1932, followed by my sister Antje, who was born 7 April 1937. It was extremely cold that year, and Brigitte remembered my mother saying that there had been little money for coal. They had no heat and ‘could scrape the ice off the inside walls’ of their small apartment. To keep the new baby warm, Mother and Father placed her between them in their bed, but were afraid to move for fear she might be smothered during the night.

One of the first major breakthroughs during my research came when I finally received word from the Berlin Document Center that all existing reference material had been moved to the National Archives in Washington DC. Grateful that I could now correspond in English – and after the usual bureaucratic red tape – I located the transcripts taken at Nuremberg of Father’s pre-trial interrogations.

I received the transcripts on microfilm, which I took to the local library to view. As I threaded the film onto the ancient machines, I was filled with a strange mixture of happiness at receiving this tangible piece of evidence and fear of what I might learn.

As I read, a knot formed in the pit of my stomach. Some of the testimony was damning – not only from witnesses, but also from my father himself, who was clearly lying about what he knew. I left the library, my head reeling. Was my father really responsible for the murder of hundreds of prisoners as the witnesses claimed?

As with most of the documentation that I would accumulate throughout the next few years, these transcripts were in German and I began the diligent, lengthy and incredibly emotional task of translating my father’s testimony into English. It was as though I found myself back in time at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice with my father, and I can almost see him on the witness stand. In my mind’s eye, I am experiencing these dramatic hearings. I wonder if his obvious lies are due to the oath he had pledged to Hitler, promising obedience, loyalty and of course the code of secrecy. Here was his testimony about the beginning.

Transcripts of Pre-trial Interrogation at Nuremberg: U.S. Military Chief of Counsel for War Crimes/SS Section Taken Of: Arthur Wilhelm Liebehenschel – by E. Rigney Date: September 18, 1946 – 10:00–11:30 a.m.

Q: Did you ever belong to any other political party before 1930?

A: No.

Q: Did you ever belong to any other political organization other than the Union?

A: No.

Q: When did you join the NSDAP [Nazi Party]?

A: 1932.

Q: Did you ever hold any leading or subordinate office within the NSDAP?

A: No I joined the SS.

Q: We’re now talking about the ‘Party’. Did you ever hold any official position in the party?

A: No.

Q: Never?

A: No.

Q: What other formation within the party did you belong to?

A: I joined the general SS.

Q: Since when?

A: Also since February 1, 1932.

Q: With what rank did you start in the SS?

A: I started as private in the SS.

Q: I’d like to go back to the question of the ‘Party’. You said you held neither rank nor a position in the ‘party’ itself. Did you ever hold any official functions in the party?

A: No.

Q: Did you have personal friends that were members of the party?

A: That I don’t know. I had virtually nothing to do with the party itself. The SS was automatically assigned to the ‘party’. We had little or no involvement with the party. We paid our dues.

Q: So the answer then to my question from a logical point of view would be: ‘Yes’ that your friends within the SS were also members of the party?

A: As you wish.

Q: What was the general reason that you joined the SS?

A: This is how it was at that time: Since I was unemployed after twelve years, one needed to seek an occupation, but there was no employment for some time. I wanted to have some activity; something to keep me occupied. That is why I joined the SS. At that time the SS was still seen as a military branch with decent people.

Q: That’s a matter of opinion. We are not here to discuss our ideas.2

Later, when Dieter and Brigitte had whooping cough and Antje was just a tiny baby, mother was afraid Antje would also become infected. Therefore, they were sent on a train with identifying name tags to Zuellichau, to Oma, our mother’s mother. Oma lived alone in a large old house in the city, as our grandfather had died in June of 1936. Dieter and Brigitte found her apartment fascinating. It was quite dark inside as the bedroom had no windows. The heavy overstuffed furniture was of old craftsmanship. The large dining table was beautifully carved wood covered by an old-fashioned, long-fringed tablecloth that nearly reached the floor.

Brigitte recalled how Oma was very strict, but a wonderful lady. She stood for no nonsense concerning picky eating habits, something Brigitte was known for. My sister preferred eating snacks between meals and Oma warned her that if she didn’t clean her plate, she’d have to wait until the next meal. My sister showed her rebellion by taking a newspaper under the table and proceeding to eat it piece by piece.

Oma could not get angry when she found Brigitte pouting and peering through the long fringes of the tablecloth. But she too was headstrong and made no attempt to offer any snacks! I suppose there was a lesson learned, but who was the teacher?

It was 6 January 1929 and Hitler appointed Himmler ‘Reichsführer SS’. Himmler was placed in charge of the original SS troops, the black corps which were the elite guards, a select group of young men eighteen to twenty years of age, pledged to protect Hitler with their own lives.

Himmler, as most of the youths of that era, including my father, seemed to be driven by a strong belief in complete order and discipline. History tells us that after the war many Nazis testified ‘they were only following orders’. In the interesting book Hitler’s Elite by Louis L. Snyder, the author cites that historians who have researched the psychological aspect of this behavior, have called this conduct the ‘obedience syndrome’. The foremost golden rule was to respect authority and to obey law and order.

Adulation of the government and complete subservience to authority was the sign – and expected of all model citizens. It was not only taught within the home and family, but even the educational system of that time was indoctrinated by teachers spreading the philosophy of Georg Hegel. Disobedience was considered betrayal to the Führer and the Fatherland.

At the onset of Nazi rule, Himmler was involved with the earliest concentration camps, which had been constructed at Dachau near Munich, then Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen by Berlin. These ‘correctional institutions’ were soon turned into death camps. Later, the Reichsführer would be the one to make life exceedingly difficult for my father.

My father joined the general SS as a private in February 1932 and became ‘Party’ member # 932766. He became a part of this elite and powerful organization, which Himmler built into a private army and police force by using highly specialized training. In 1933 the ranks of the SS had a membership of 52,000 men, escalating Himmler’s power, and soon he had complete control of the German people. The Death’s Head Units of the SS (Totenkopfverbande) were established and its members were primarily employed as concentration camp guards.

At the time I joined the SS, I automatically and also voluntarily, became a member of the NSDAP [Nazi Party], in which I never held any official offices. In accordance with the propaganda of the SS at that time, I informed my superiors in 1938 that I had relinquished my faith and religion and was no longer affiliated with the Protestant Church. In actuality, however, I remained a member of my congregation and continued to pay my dues. I never officially acted out my separation from the church. I hid the truth from the SD to avoid their punishment.3

The young and most able were formed into a specialized battle unit in 1940. The ‘Totenfkopf’ Division became part of the Waffen SS (Military Division). These troops were not involved with the concentration camps. Those members who were wounded or elderly, unfit for the front, were – as in my father’s case – put in charge of the concentration camps.

My father took the oath of ‘nobility and honor’, the same oath taken by the military forces:

I swear before God this holy oath, that I should give absolute pledge to the Führer of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, the Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht, and as a courageous soldier will be ready at all times to lay down my life for this man.

With Hitler in power, Joseph Goebbels, the ambitious Minister of Propaganda, waged his skillful campaign by showing the Führer kissing babies, children bringing him flowers and playing with his animals, and showing him on newsreels in theaters to convince people of his fondness for children and his goodness of heart. These clever lies built Hitler’s national image, and fooled most of the public.

It was during this time of desperate economic decline that to many – those who chose to join the Nazi Party or the SS – it was merely a job. In a bleak time of unemployment, hunger, bankruptcy and despair, Hitler had come along with the answer to regain economic strength. One has to wonder how many people would have chosen to participate in Hitler’s ‘workers’ party’ had they known the extremes of the end result, as we know it today.

Those people, however, who were not sympathizers of the Nazi Regime, were threatened to enlist against their will. In order to keep their jobs many became non-active but paying members.

It is easy to comprehend why my father made the choices he did at the time. He must have sensed renewed hope with the Nazi regime and was readily caught up to Hitler’s ideas of a more prosperous Germany. The army had been his career for twelve years and he was drawn toward the strict military discipline of the SS. Joining this organization seemed the right thing to do at this point in his life. Brigitte recalls him as ‘a gentle man who saw only good’.

When Father started his career in the administrative part of concentration camp duty, the camps were set up more like penitentiaries for political prisoners. Later they became the death camps, as we know them today. Did my father realize the horrific implications connected with this organization when he joined? I will never know the answer to this nagging question. Later my father confessed to my brother Dieter and sister Brigitte that, had he known in the beginning what he knew then, he would not have taken the path he did. He also did not want his son Dieter to join the SS.

In the beginning of Nazi rule there were some positive things happening for the general good of the country’s economy. The economy was slowly improving with numerous jobs created through the construction of the Autobahn, which was completed in 1937; factories were booming and building construction put thousands of people to work. Every family consisting of two or more children was subsidized twenty Marks per child, which was finally putting food on their barren tables. Even special care benefits were given, like free summer camp for children from poor families. Because of this upward movement, people were obviously fooled and convinced that Hitler, who seemed to be liberating them from their crisis, was the suitable leader for Germany.

Since August 1934 Father was no longer working for the Finance Office, but became adjutant and head of staff personnel of the 27th SS Regiment, serving for the Kommandant in the Lichtenburg Concentration Camp. At the same time he was Section Chief of the Politische Abteilung at Columbia Haus in Berlin. Columbia Haus was a concentration camp, which held prisoners under interrogation at the Gestapo headquarters. It became infamous for the torture methods used there.

When we lived in Prettin, on the river Elbe, he was part of the unit SS-Wachtgruppe ‘Elbe’. Here he was the adjutant to the Kommandant of the Lichtenburg Concentration Camp. From July 1937 he was department head and part of the staff of SS-Obergruppenführer Eicke until 1940. It was here in Prettin that my sister Antje was born in 1937.

The ancient Lichtenburg Camp had once been a monastery which was built during the fourteenth century, in the time of the Renaissance. In the years 1575–81 Prince August of Sachsen occupied the three-winged structure and it became his palace. Before it became a concentration camp it was used as a penitentiary for political prisoners. My parents lived across the street and my brother recalls how he used to squeeze through the large iron gate at the entrance. He made it a habit to always wander off and would be found playing inside the courtyard.

Dieter started grade school here, and Brigitte’s memories are of the tinker man, who came around with an old small rickety truck. He would trade old newspaper or tin foil with the neighborhood children in exchange for small gift items. Once Brigitte had saved a huge stack of newspaper and in return she was given a blue ‘pearlized’ glass necklace. It was her special treasure she would keep for many years.

It was also at this time, by orders of the SS, that a complete genealogical history of my parents was documented. It traced back to the year 1800 and proves their ancestry stemmed from ‘pure Aryan’, non-Jewish blood. This was absolutely mandatory for all SS and party members.

My father became gravely ill at this time, diagnosed with an infection of the heart muscle. Doctors gave him little hope, but having a very strong will for survival, he miraculously pulled through and recovered. Apparently his heart was left damaged and he was to suffer from this the remainder of his life.

As a result of the weak heart disability he was permanently reassigned to administrative office divisions, within the framework of concentration camps. Incapable of performing his duty regularly during the three-year period of his illness, he was, however, paid 250 Reichsmark monthly by the SS.

At some time throughout his career my father was awarded the ‘Orden & Ehrenzeichen’ (Medals & Decorations) of the Wartime Cross of Merit I & II. He was also given the SS dagger and ring.

Transcripts of Pretrial Interrogation at Nuremberg: U.S. Military Chief of Counsel for War Crimes/SS Section Taken Of: Arthur Wilhelm Liebehenschel – by E. Rigney Date: September 18, 1946 – [continued]

Q: Now we come to your first office position within the SS, after you left the Finance Office in Frankfurt-Oder in 1935, is that correct?

A: It was 1935.

Q: At that time you started a position in the SS. What was the position?

A: Head of Personnel and Adjutant of the 27th SS Regiment.

Q: Where?

A: In Frankfurt on the Oder.

Q: Who was your superior?

A: Lt-Colonel Gerlich.

Q: Until when was Gerlich your superior?

A: Until the end of February 1934.

Q: How long did you work for the 27th SS Regiment?

A: Approximately until March 1935. Then I became ill.

Q: How long were you ill?

A: Almost three years. I had severe pneumonia, a relapse, and also an infection of the heart muscle. I was unable to work for almost three years.

Q: Were you in the hospital?

A: Yes several hospitals.

Q: What did you live on for three years?

A: I received a salary of 250 Reichsmark from the SS.

Q: Monthly?

A: Yes.

Q: What was this equivalent to, as far as rank?

A: At that time it was not about rank. It was simply a legal settlement according to individual status.

Q: When did you resume your duties? In 1938?

A: In 1938 I started working for the SS Main Office (Hauptamt).

Q: Under what title?

A: Department Chief.

Q: In which section?

A: In the Department of Weapons and Equipment.

Q: How long were you at the Main Office in Berlin?

A: Until I was transferred to the Economic Administration Department in January of 1942.

Q: What were your functions within the Main Office?

A: There, I was in the section for Weapons and Equipment.

Q: What was your duty?

A: My tasks were checking the books of various units, keeping files and count of weapons and equipment.

Q: Were there any other tasks within the Main Office, leading or subordinate duties?

A: I was only assigned to do office duty, as my health would only allow.

Q: I didn’t ask you if you did office work. I asked if you performed other duties within the SS Main Office?

A: No.4

Father’s health was slowly improving and he was promoted to Chief of the Political Department at the SS Main Office, Columbia Haus in Berlin. My family moved from Prettin to # 45 Hoeppner Strasse, Berlin, Tempelhof. Father’s superior officer at that time was Captain Weinhoebel who was later killed at the front.

In 1938 my family moved once again, this time to Sachsenhausen. It was our first actual home, a small two-story house, a definite step-up from previous apartment living. It was located in a housing tract for SS officers.

Rudolf Hoess was the Protective Custody Commander at this time at the camp Sachsenhausen, and would later become the first Kommandant of Auschwitz from 1940–43. He and his family lived next door to us in Sachsenhausen. My sisters were never fond of him or his family. Their two sons ‘were mean and cruel’ according to my sisters, who were always invited to all the boys’ birthday parties. My parents insisted they attend but usually against their wishes.

Across the street was a beautiful forest of mixed trees, pines, birch and others, a wonderful playground for the neighborhood. The Hoess children used to tease and chase Brigitte in this forest. One day they chased her, causing her to run so fast that she fell and badly cut her knees. Bleeding and crying she headed home. Father comforted her and told her after he washed and bandaged her knees that he would teach her to ride her new two-wheel bicycle. He held on to the seat, assuring her ‘Brigittchen you can do it!’ while she peddled faster and faster. Soon she no longer heard his voice and when she turned around and saw him waving to her from a distance, she realized she had been riding on her own. She had forgotten all about her painful scrapes; however, the scars that were left on her knees would always remind her of those wicked Hoess boys!

Our home was only a short distance from the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, which had been established in 1933. Among the captives were political opponents, churchmen, communists, homosexuals and Jews. Many of the Jews had been sent here after the 9 November 1938 twenty-four-hour street violence known as ‘Kristallnacht’. This was the destruction of synagogues, the breaking into of thousands of Jewish shops, and the demolition of dwellings and homes. Countless books on philosophy, history and poetry were burned. Those arrested were released two to three months later, but many had already perished.

For some time the Sachsenhausen Camp was also set up as an extensive Brick Works. Prisoners were forced to work to meet the availability of building materials for the many elaborate projects planned for the rebuilding of the empire – the Reich – according to Hitler’s dreams, and were carried out by his architect, Albert Speer.

After the war the Sachsenhausen Camp, like numerous others within the area, was established as a ‘Special Camp’ by the Soviets. Over 60,000 civilians were incarcerated there, intended for long-term imprisonment. Among them were low-to mid-ranking Nazis, members of the German Army, Soviet concentration camp prisoners who were accused of being traitors, and even victims of totally arbitrary arrests. These people included over 2,000 women, who were required to perform forced labor for the development of the Soviet Union.

In 1946–7 in this camp alone over 12,000 died of hunger and disease, and were buried in mass graves within the camp’s perimeter.

Our grandmother from Zuellichau came to stay with us for a few months while we lived in Sachsenhausen. She was not well and our mother was going to look after her. Bedridden with a heart condition, she unbelievably ‘smoked like a chimney’. Brigitte was her favorite and when Brigitte went in to visit her early one Sunday morning, Grandmother was still sleeping. Brigitte wondered why her arm was hanging down to the floor. Brigitte told Mother, ‘Oma must be feeling better because she’s still resting this morning.’ Yes, Oma was resting … but forever.

Antje was two. She also found Oma lying very still in her bed that morning. She climbed on top of her and with the chocolate bar from her nightstand, she went on to feed Oma and herself the sweet, rich chocolate bar. When they discovered her she was sitting on Oma’s chest, whose entire face was covered with chocolate and only Antje’s large expressive eyes were recognizable, looking back at them with sheer delight.

As was the custom, Oma was laid out in the parlor in her coffin and Brigitte was made to kiss her goodbye. Into adulthood, the traumatic memory of Oma’s cold body remained to haunt her.

It was about this time that Antje really started talking and could not say ‘Brigitte’. One day she looked at her and called her ‘Gitscha’. She was Gitscha to all of us until she passed away in 1988.

By 1939 the threat of war was imminent, due to Hitler’s aggression toward Germany’s bordering countries, and before long the Second World War would rage throughout Europe in earnest. Any desire my father had for a normal family life was soon shattered by the overwhelming demands of war.

Chapter One: Party Member # 932766 & Family Man

1.Trial Testimony May 7, 1947, Auschwitz Archives.

2.Nuremberg Interrogation from National Archives microfilm, publication M1019 [roll 42] dated 18 September and 7 October 1946. Records of the United States of Nuremberg War Crimes Trials Interrogations 1946–49.

3.Trial Testimony May 7, 1947, Auschwitz Archives.

4.Nuremberg Interrogation from National Archives microfilm.

Chapter Two

Oranienburg

The year was 1939 when my father was relocated and the family moved to Oranienburg near Berlin, a short distance from Sachsenhausen. Here in my imagination, I can picture the man in the photograph as he walked the streets of quaint, historical Oranienburg; as he sat at his desk, working on the endless stacks of paperwork of the Third Reich; at home as he hung the glittering tinsel on the family Christmas tree while my mother looked on. And I see my siblings as happy children totally unaware of what fate their tragic future held.

German troops marched into Czechoslovakia on 15 March, and Hitler announced, ‘Czechoslovakia ceases to exist!’ Poland was invaded and occupied by German forces in September of that same year. The war had begun.