13,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Jonathan Ball

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

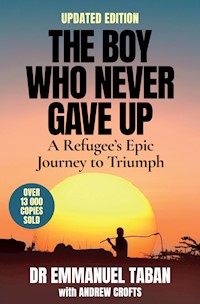

In 1994, 16-year-old Emmanuel Taban walked out of war-torn Sudan with nothing and nowhere to go after he had been tortured at the hands of government forces, who falsely accused him of spying for the rebels. When he finally managed to escape, he literally took a wrong turn and, instead of being reunited with his family, ended up in neighbouring Eritrea as a refugee. Over the months that followed, young Emmanuel went on a harrowing journey, often spending weeks on the streets and facing many dangers. Relying on the generosity of strangers, he made the long journey south to South Africa, via Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, travelling mostly by bus and on foot. When he reached Johannesburg, 18 months after fleeing Sudan, he was determined to resume his education. He managed to complete his schooling with the help of Catholic missionaries and entered medical school, qualifying as a doctor, and eventually specialising in pulmonology. Emmanuel's skills and dedication as a physician, and his stubborn refusal to be discouraged by setbacks, led to an important discovery in the treatment of hypoxaemic COVID-19 patients. By never giving up, this son of South Sudan has risen above extreme poverty, racism and xenophobia to become a South African and African legend. This is his story.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

THE BOY

WHO NEVER

GAVE UP

A Refugee’s EpicJourney to Triumph

DR EMMANUEL TABAN

WITH ANDREW CROFTS

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS

JOHANNESBURG · CAPE TOWN · LONDON

CONTENTS

To my mother, Phoebe Kiden Stephen,

and my father, Bishop Giuseppe (Joe) Sandri.

May they rest in peace.

LIST OF MAPS

Map of Sudan and South Sudan

The first leg of my journey: through Eritrea and Ethiopia

The second leg of my journey: through Eritrea, Ethiopia and Kenya

The third leg of my journey: from Kenya to South Africa

PROLOGUE

‘I will kill you like George Floyd!’

A droplet of spit fell on my cheek and I could smell the breath of the Tshwane Metro Police officer. His angry eyes bored into mine.

Seconds earlier, he and his partner had shoved first my wife, Motheo, and then me into their police van. It was a clear act of intimidation. They had pulled us over after I had crossed a solid white line while overtaking another vehicle. I don’t normally disobey traffic rules but I was in a great hurry to get to Midstream Mediclinic in Centurion, where one of my COVID-19 patients was in the intensive care unit (ICU).

‘Where’s your phone?’ he shouted. Another droplet of spit.

‘It’s in my car,’ I lied. I had secretly slid it over to Motheo, whispering to her to send to a friend the photos and videos I’d taken of the vehicle registration number and the cops’ faces. But they were all over us and she was too shaken to do anything. I saw her lip was still bleeding from when the traffic cop had wrestled her to the ground and into their van.

‘Where’s the phone? I saw it on you!’

The officer got into the van and started to search my body, but to no avail. ‘I will kill you!’ The next moment he grabbed me by the throat and started to throttle me.

Motheo is South African and I am South Sudanese. My particular shade of blackness and the fact that I do not speak Sepedi had fuelled the officers’ antagonism. One of them had called Motheo a whore for being married to a makwerekwere, a foreigner.

I tried to resist but my hands were cuffed behind my back and the officer was much bigger and stronger than me. I struggled to breathe. As much as I tried to inhale, no oxygen would come in.

‘Here it is! Here it is!’ Motheo screamed when she saw my eyes rolling back into my head.

She handed the phone to the officer.

‘What’s the PIN?’

I was still gasping for air.

‘What’s the PIN?’ the officer shouted and grabbed me by the throat again.

In that moment I realised that this was the day I might die. My survival instinct kicked in and I tried again to wriggle free. The officer’s colleague grabbed his arm and he let go. I finally managed to focus on what he was saying and gave him the PIN to my phone. He deleted the photos and videos and even accessed my Facebook app, worried that I might share what had happened on social media. Then he got into the van, asking his colleague to follow him in our car as he drove us to Lyttelton police station.

In the early 1990s I fled war-torn Sudan as a 16-year-old boy after I was abducted by government forces and tortured. After my escape, I made my way south through several African countries over many months, surviving hunger, life on the street, thieves, corrupt border officials and many other dangers to finally make it to South Africa. But today not even my medical degree would save me. I had never been so afraid for my life.

Map of Sudan and South Sudan

1MONEY FROM THE SKY

As a barefoot boy in the dusty South Sudanese village of Loka Round, I was always running. Nothing could slow me down as I hurtled enthusiastically through childhood, but the pile of money that lay before me in the road brought me to a screeching halt. I had never seen anything like it, so I assumed it must be the sort of miracle, the kind of gift from God, that the grown-ups in my life had always been promising. I snatched it up.

The magical appearance of that money in the dust seemed, at that moment, to suggest that my prayers had been answered, just as the grown-ups always told me they would be.

I was about eight years old and unexpected visitors had arrived at our one-room hut, a simple structure made of mud and grass, like all the others around it. My mother had sent me out to buy a loaf of bread so that we would have something to offer our guests. As always, I set out with all the speed I could muster, running as fast as my legs could carry me so that I could get back as quickly as possible with the loaf and show them what a good and reliable son my mother had raised.

The money, however, caused me to stop and investigate. Counting each worn and grubby note, I carefully shielded my find from any predatory eyes that might be watching from the bushes on either side of the track. I realised it was about $20 worth of local currency, enough to buy any number of loaves, and more money than I had ever seen – or would see again for a long time.

I was so happy that my heart soared in my chest. I pushed the notes into the pocket of my shorts and set off once more on my mission at even greater speed, fearful that someone might have witnessed my good luck and would try to rob me. I couldn’t wait to get home and show my mother how the God she told me so much about had decided to bless me.

‘God has given you money, Bobeya!’ she exclaimed when she saw it. My nickname in the family was Bobeya, which means ‘baby’ in my mother tongue, Pojulu, a Bari language. The name stuck, even as the years passed and many other babies were born after me, each one increasing the burden on my mother, who struggled to keep them alive long enough for them to become self-sufficient.

For the next few days I doubled and trebled my prayers in the hope that even more free money would drop out of the sky and land at my feet, allowing me to help my mother feed the many empty stomachs that depended on her. It confirmed everything I had heard in church about the goodness of the Lord.

I was still too young to understand that hoping for an unearned windfall in this way was part of accepting that I was unable to earn money for myself. It was telling me that, in order to prosper, I simply had to pray and then wait for those prayers to be answered. It did not occur to me that there might be another way. Every grown-up I knew was praying for the same thing, and with the same lack of success.

To my disappointment, no more money arrived from the sky. When I thought back a few days later to the night before my windfall, I remembered lying in the dark and hearing drunk people fighting on the road outside our fence. It was not unusual to be woken by such threatening sounds, but it occurred to me that it was probably one of the drunks who had dropped the money in the dark rather than a benevolent heavenly Father.

But still, I reasoned, He had guided me to the spot before anyone else, so maybe He was just moving in ‘mysterious ways’ like they talked about in church. The incident gave me much food for thought, which my young mind was not yet ready to put into any coherent order, leaving me feeling confused and unsettled. I longed to understand things better.

Typical mud huts in Rajab East village on the outskirts of Juba

Now, after many years of travelling, reading and learning, I understand that the sort of long-term poverty I was born into is not inevitable for anyone, and it has nothing to do with God’s will. It wasn’t Him that made us poor. In fact, the Republic of South Sudan, as my country is now known, could be one of the richest countries in the world. We have a God-given abundance of oil, gold and other minerals lying under the ground, and our soil is so fertile that it is almost impossible to stop things from growing in it. Yet it is home to some of the poorest people on Earth, people who still live in mud huts like the one I was raised in, with no electricity or running water, and who seldom have enough nutritious food to prevent their stomachs from aching. My people have eyes, but they cannot see the riches of the country. They have accepted their status as victims of their own mentality.

Sudan’s development as a country was severely hampered by long periods of civil war, first from 1955 to 1972 and then from 1983 to 2005. South Sudan gained its independence in July 2011, becoming the world’s newest sovereign state. The struggle to reach that point, which filled my childhood years, was long and bloody.

Even today, life expectancy in South Sudan is still about half what it should be, partly because of the lack of clean water, basic hygiene, education and effective medical care, and partly because of the country’s murderous political history. A country that should be close to paradise more often looks like hell to those who visit or watch from the outside.

I was born on a mud floor in Juba, now the capital of South Sudan, to a single mother in 1977. My statistical chances of surviving into adulthood were never good. But, like all children, I never realised that there was anything I could do to improve the odds beyond offering up prayers to God when instructed to do so, and hoping for at least one miracle to come to my rescue.

I accepted my own helplessness to influence my fate just as everyone around me accepted theirs, and just as the majority of people in South Sudan still do. Because of that acceptance, and because of the strength and goodness of my mother, my early years were happy despite the poverty and adversity that to me seemed normal.

I was the youngest of the four children that my mother had with my father, Lemi Sindani. My mother, Phoebe, was a hardworking woman whose entrepreneurial skills had to compensate for her lack of education and family support. She made a mistake when she married my father, who proved to be an incorrigible philanderer, and they eventually divorced while she was pregnant with me.

Shortly after my birth Phoebe’s brothers, my uncles, decided that she should move out of Juba and back to the village of Loka Round in Lainya County, where she had been born and brought up. I suspect that they felt a divorced sister would be less of a responsibility for them if she was safely hidden away from the city. One of my dreams, when I grew old enough to understand the true situation, was to make it up to her for all the suffering she went through on our behalf as she struggled to keep us alive.

Loka Round was about 77 kilometres southwest of Juba and consisted of two churches, a school, a small shop, a carpentry workshop, a clinic and a few mud huts. Our family had a compound of around three hectares on which we grew vegetables, nuts, maize, cassava and beans. Everyone worked together to help grow enough food to survive the regular famines caused by the fighting between the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA),1 a guerrilla movement founded in 1983, and the government of Sudan. Under its leader, John Garang de Mabior (1945–2005), the SPLA fought for a secular and multi-ethnic Sudan whose citizens would unify under the one commonality they all shared – being Sudanese.

The graves of my grandfather and my uncle, at the centre of the compound, are now the only things that remain after the village was abandoned and looted in 1986 and the walls of the houses crumbled back into the earth they were made from. My grandfather died soon after our return from Juba, but I can just remember him. He had a limp, and the story told around the evening fires was that when he received a dowry for his eldest daughter, he was supposed to give it to his uncles, who had raised him, but he spent the money instead.

The uncles, who believed that he owed them the money for everything they had spent on him as a boy, were said to have put a curse on him, which resulted in his being knocked off his bicycle by a buck and breaking his hip. As children we were told this cautionary tale to teach us that we should always take notice of what our uncles said to us; if we displeased them and they cursed us we might well end up being punished in a similar way. We listened carefully to the warnings and took them to our hearts.

My grandfather was among the few people from our tribe, the Pojulu, to receive a formal education during the 1960s. In many ways, this set him apart from others. He had two daughters, including my mother, and four sons, Manas, Nasona, Martin and Alex, all with the same wife. In the absence of our father, my uncles played a role in my upbringing, even though it was usually unwillingly.

Having sent my mother back to the village, the family built her a simple one-room mud hut with a grass roof in the same compound as her parents. (Many of the mud huts you’ll see in South Sudan today are still built the same way they were centuries ago.) Inside, the hut was always dark because the windows were small and did not let in much light. It was often smoky from the candles that we burned for light. The wooden window frames never contained any glass, just metal netting to keep out the bugs.

We entered through a doorway so small it forced us to crouch, and the floor was made from dried cow dung. At Christmas the tradition was to mix cow dung with ash, which creates a white paste. A broad white strip was then painted around the lower end of the hut and the paste was also used to decorate the outside walls with patterns. Outside each hut there was a gugu, a round container made from bamboo mesh and cow dung that stood on stilts and was covered by thatch. This was where we’d store mealies and dried meat, mostly goat but also some game.

Cooking was done outside over open fires. There was a borehole at Loka Round Secondary School that supplied water to the whole village. Later we got another, but it was a few kilometres away. We had no sanitation and had to relieve ourselves in the veld, using leaves to clean ourselves. We bathed in a nearby river and also washed our clothes there.

When the weather allowed, most people preferred to sleep on mats on the ground outside, breathing the fresh night air. My mom and I would often lie like that and gaze up at the clear skies above us. Often we would see the planes coming from the south of the continent and heading north. As a young boy I promised her that I would take her to Europe. ‘One day I want to sit up there in the plane,’ I would tell her.

To some it might seem that we lived in the Stone Age, but I remember a joyful childhood in Loka Round. We didn’t have any material possessions, and bicycles were only for the rich – another reason I ran everywhere – but we were very happy kids.

Also living in the compound were my mother’s brother, Manas, his wife, Joyce, and their six children. Manas died of pneumonia when I was still small and he was buried next to my grandfather. Manas and Joyce’s son, Thomas, whose nickname was Yaka, was the closest to me in age and was to become my best and closest friend in the coming years.

Aunt Joyce, who no doubt had her own demons, would often drink during the evenings and would then weave her way home, stopping outside our house and singing loud songs about us, calling us dogs and all sorts of other derogatory things. This would lure my mother out to argue with her in front of anyone who cared to listen. As a widow of one of the brothers, Aunt Joyce’s standing in the family was apparently higher than that of my poor divorced mother.

When we moved from Juba in the late 1970s, my mother started working at the Loka Round Secondary School, where I would start my education a few years later. It was a sturdy stone building with its own playing fields. If it had been allowed to survive it would no doubt have produced many generations of future leaders for South Sudan, but instead it is now just a ruin, the walls slowly being reclaimed by the bush.

My mother got as far as Primary Two (Grade 2) in school, so she could write her name and read a bit, but not much more. We had a Bible in the Bari language that she was able to read to us. Her schooling was cut short by her decision to marry early, whereas some of her siblings went much further. Her one brother, Nasona Stephen, even studied accounting at Makerere University in Uganda and went on to become Commissioner for the Corrections Service in Juba.

The school had been built by the British and included the Episcopal church, where we sometimes went to worship, and soccer fields for us to play on. There was a more basic local village church as well, built from grass and mud, which was where we attended services most often.

My mother was a deeply religious woman. At Christmas, we children would walk from village to village with big drums, spreading the word of God, praying with people and being given nice things to eat. Sometimes we would travel as far as ten kilometres and not get back home till the early hours of the morning. The boys would also go to the local tailor and ask for small pieces of colourful material, which we would then string up in the trees outside our hut. On Christmas Day everyone would gather to feast all night. It was a wonderful time for me because I knew of no other world beyond the village and was simply glad to be alive.

When my mother was growing up in Loka Round in the 1950s, it was a dark and dangerous time. The people who lived in the villages suffered grievously in the civil war that was already raging when the country gained independence from Britain in 1956. From the start the southern states were unhappy about their lack of autonomy, and the fighting went on until 1972 when the South was promised a level of self-government. When the Sudanese government eventually reneged on these promises, the civil war flared up again in 1983.

It must have been particularly frightening for a young woman, for rape was an accepted weapon of suppression and war among soldiers on all sides. When things finally became too dangerous, she, with many thousands of others, abandoned her home and fled south into Uganda in search of safety. It is easy to imagine how susceptible she would have been to any young man who showed her affection and made her promises of marriage and security.

It was in a refugee camp in northern Uganda in the late 1960s that she met my father, who was another South Sudanese refugee from a village no more than seven kilometres from that of my mother’s family. His family, being mostly carpenters and tailors, would have been considered to be of lower social status to hers, which may have been why her family did not much approve of him or of the match. She was still only about 17, however, and easily influenced.

I dare say that any romantic dalliance was a welcome distraction from the tedium and discomfort of living in a refugee camp. Any young couple who were known to have been intimate, however, were expected by their families to marry, so I doubt she gave the matter much thought before committing to a path that would bring her and her children much sorrow. She was an intelligent woman with a keen mind for business, but she was not empowered enough to be able to make wise life decisions.

And so the young lovers married and had my brother Joseph, nicknamed Lotola, followed by my sisters, Agnes and Diana. They were all born while my parents were still living in Uganda, but then they moved to Juba and my mother fell pregnant with me. It was at this point that my mother finally had to admit to herself that she had to get out of the marriage. My father was a truck driver who was always away from home. Like many truck drivers, he often had affairs with other women.

Because my mother took the brave decision in Juba that she would be better off without him, and got a divorce, I never really knew my father and he played no part in my upbringing. To all intents and purposes, I was a fatherless child, and I wanted nothing to do with him. I felt no bond and no affection for him. I relied on my mother for everything.

In his adjudication of the divorce, the village chief decided that once I was born I would belong to my mother, as would my sister Diana, who was the next youngest, while Joseph went to live with our father and was left in the care of our paternal grandfather in their village whenever our father was away working. Agnes went to live with our mother’s sister, Aunt Esther. Without a father who could be relied on to support us we had become a burden that the family had to share out.

Whenever my father did turn up at our house in the village, which was seldom, he would try to show an interest in me, but I didn’t want anything to do with him and would run away and hide in the bush until he had gone. My older siblings would hang around the house in the hope that he would bring some bread or bananas to hand out to them but I just wanted to get away.

My older sister Agnes with her children

Sometimes he would bring us clothes, but I would refuse to wear them, only wanting to accept things from my mother. I guess I felt rejected by him even though I wouldn’t yet have understood what that meant. He didn’t seem a violent or frightening man. Like my brother, he appeared to lack self-confidence and had a strange, lazy way of walking that made him look a little simple. On all these visits he and my mother would always argue about the money he should have been giving her to help with our school uniforms and other responsibilities.

My youngest brother, Kennedy (right), with friends

It was always exciting when Mom gave us new shoes because it meant we were able to run around without being pricked by thorns, but they were only ever slippers or sandals and soon wore out. We also made flip-flops from thick leaves or tyre strips when we could get them.

Mom did everything she could to shoulder her share of the responsibility for her children by selling sandwiches and alcohol in the street market. She worked every day, leaving home in the morning and only returning to us at night, sometimes with a bit of food if she hadn’t managed to sell it all. My sister would try to cook during the day, making a sort of soup using porridge and eggs, and in the evenings she and I would sit and talk with our mother as she told us stories and plaited Diana’s hair.

Our grandmother, who lived in a hut across the compound, was very kind to us. There were always yams (sweet potatoes) and other vegetables for us in her house and she was probably the only person in the wider family who loved us and did not resent having to help us after my mother divorced my father. She used to make medicine from local plants for anything from headache and chest pain to diarrhoea.

As my grandmother’s house gradually melted away in the wind and the rain, the family built her a smaller one on the same plot. At that time, it seemed normal to me that houses had finite life spans, just like animals or people. It didn’t occur to me that we should be using bricks or other more durable materials.

Grandma used to take us hunting for flying termites. Everyone in the village was allowed to mark out the giant termite mounds in the surrounding bush as their property and she would always have four or five of them in her name. When the rains came she knew that the termites would be coming out at night and so she would take us hunting. Under her direction we would surround the mounds, which could sometimes be a metre or more in height. We would then set fire to bunches of sticks and wave them around so that the light would attract the termites out of the mound into our traps. When they come out, their wings fell off and they tumbled to the ground.

We collected the termites in buckets. Once we had enough, we would take them home to dry and store so that we could eat them during the winter, when there would be less food on the trees and in the ground. We would cook them in bicarbonate made from the ashes of pumpkin leaves and mash them into a delicious sort of meatball the size of a small fist.

One year we were out on a night-time hunt with Grandma when she suddenly held up her hand.

‘Shhh!’ she hissed.

We fell silent but heard nothing. Grandma threw a stone towards the sound she had heard and a snake reared up in the light of the flames, rushing towards its hole as we rushed, equally fast and screaming loudly, back home. Snakes were the things we feared the most in the bush.

Every year we would become excited when the grasshoppers arrived because they also made a tasty snack when fried in oil and mashed to a pulp. However, the snakes were just as interested in this food source, and one day a large snake I hadn’t spotted darted in and snatched my catch off the skewer while it was still in my hand.

As well as selling alcohol and sandwiches, my mother also got a job looking after the boarders at Loka Round Secondary School. Her duties covered everything from seeing to the children to making the headmaster’s tea and running his messages. All through my life I have met people who knew her when they were pupils at the school during those years and remembered the kindness she showed them. She used her meagre salary from the school to hire workers from Uganda before the rainy season to dig and level the ground around the compound so that we could plant our seeds for the following year.

We also had about a dozen goats, which had to be taken out into the bush each day to graze. This was a job for us children and we had to stay constantly alert to stop them from escaping into someone else’s crops and causing disputes with the neighbours. We drank their milk, and if a goat became sick we would slaughter it. We had no way of keeping the meat fresh so we would eat the stomach immediately and then hang the rest up to air-dry. The dried meat would be rationed out over the coming months.

Sometimes we would go hunting for small buck or set traps for squirrels and small birds. There were always chickens running around the compound, scratching for worms in the bare earth and laying their eggs in places where we had to search for them, otherwise the snakes would get to them before us. And we could always help ourselves to wild mangoes and guavas from the surrounding trees.

When we had enough fruits to spare we would carry them on our heads to the roadside and sell them to passers-by, waving to the cars to encourage them to stop so that we could conduct our business through the open windows, chattering cheekily, with outstretched hands and pleading eyes.

We didn’t have dogs of our own, but sometimes feral packs would come scavenging around the village. We knew they could be infected by rabies and we would have to run for our lives because one bite would be a death sentence. The adults would then hunt them down and kill them with pangas (machetes) if they caught them. There was no other way to stop them.

As I mentioned, I got on particularly well with my cousin Thomas, whom we called Yaka, and we often got into trouble together. One day we were playing together in the family compound and, for some reason I will never understand, Yaka decided to set fire to our grandmother’s mud hut.

‘What are you doing?’ I shouted, horrified as soon as I realised what he was planning, but it was too late to stop the flames from spreading through the dry grass on the roof.

All her meagre possessions were destroyed in the crackling blaze. We ran and hid until it was dark, the flames had been doused and we had grown hungry. The grown-ups blamed both of us and, as was the tradition, a cross was drawn on the ground which we had to step over so that my grandmother would forgive us. Yaka crossed it willingly, but I wasn’t going to take the blame for something I hadn’t done, and refused to step over. Even then I was showing signs of being stubborn about such matters.

My stubbornness, however, made Aunt Joyce very angry. She didn’t believe my mother and her children should even be living in the compound, and I expect she was sure I had led her son astray. I was thoroughly beaten for the incident and it certainly wouldn’t be the last time that happened. So I started gaining a reputation with some members of the family for being a troublemaker.

The alcohol that my mother made and sold was called ciko. She never allowed us to even taste it, and I wouldn’t have wanted to anyway. Sometimes I saw quite educated people, such as teachers, coming to our house late at night and getting drunk on it. I didn’t like the aggressive noise they made with their singing in the street and the way they fell about and picked fights with one another over nothing. I couldn’t understand why normally dignified grown-ups would want to do something like that. It didn’t make sense. Now I can see that it was their way of dealing with the frustrations of their lives, an escape from reality, but it only ever made their problems worse. No one can work or look after a family effectively if they are drunk all the time.

My mother would also bake bread and sell sandwiches topped with beans. Her every waking hour was spent either working or looking after us. She never had a moment’s rest, and in her heart she must have been lonely despite the fact that there were always people around, most of them wanting something from her.

When I was about six she fell in love with one of the teachers at the school, a man from the Kuku tribe, and fell pregnant with Kennedy. I witnessed the whole birthing process in the hut. It was a traumatic experience for a small boy to hear his mother screaming in pain and to see so much blood. The picture was carved deep into my memory as I watched Kennedy emerge onto the bare dung floor.

When people ask me today why I work so hard, I tell them that when I was born, like Kennedy, I had no mattress to land on, that I immediately hit my head on the hard floor. I want to make sure that my children all have a soft landing when they arrive in this world. In other words, the poverty that our family experienced over the last few generations must end with me.

I assume that the Kuku teacher was just using my mother, because he made no effort to live with us or to be a good father to Kennedy. On the one hand, I suspect my mother hoped she had found someone who would help her shoulder the burden of parenthood. On the other hand, perhaps she just gave in to the temptation of a moment of pleasure and excitement in a life of otherwise unceasing struggle and loneliness. Since there was virtually no health care available in the area, she had no access to contraception. Even a passing dalliance like this would have offered some warmth and comfort to a young woman who spent every hour of every day working or caring for her children.

Table of Contents

Title page

Contents

Dedication

List of maps

Prologue

1. Money from the sky

2. A studious boy

3. Life and death in Juba

4. Abduction and torture

5. Stuck in Asmara

6. On the streets of Addis Ababa

7. Fighting off thieves and snakes

8. A home with the Combonis

9. A single-minded student

10. Becoming a doctor

11. A sad reunion

12. Trying to make a difference in South Sudan

13. A wedding and a funeral

14. Farewell to my father

15 On the front line of a pandemic

16 The second half

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the book

About the author

Imprint page