Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

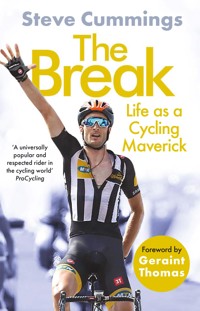

*SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2023 SPORTS BOOK AWARDS CYCLING BOOK OF THE YEAR* The gripping and revealing autobiography of one of Britain's most successful international cyclists of the modern era 'Getting in a break was my one chance of winning. The hard part was working out, again and again, how to make that chance count' Sharp, resourceful and a permanent outsider; for nearly 20 years Steve Cummings determinedly blazed his own winning trail in international cycling. A maverick who defied the dominant teams, to record a sequence of gloriously improbable victories, he has lived and raced with legends of the sport - Cavendish, Wiggins, Froome, Thomas and others - about whom he has strong views and untold stories. This autobiography of one of Britain's most successful international riders of the modern era takes the reader from Steve's earliest days as a junior, pounding across the flatlands of the Wirral, through his love-hate relationships with the British Cycling track cycling squad, to his series of top-level breakaway victories in the Tour de France, Tour of Britain and Vuelta a España and - rather than standout physical talent - how developing his own strategies and training techniques enabled him to succeed against the odds. The Break will be the first full-length account of the life and times of, in the words of ProCycling magazine, a 'universally popular and respected rider in the cycling world'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 500

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Born on the Wirral, Steve Cummings was a track rider for Team GB from 2001 to 2007 before racing for top pro teams including Team Sky, BMC and MTN-Qhubeka-Dimension Data. He achieved two of the most spectacular stage race victories in recent Tour de France history: at the mountaintop finish in Mende in 2015 and through the Pyrenees in 2016, as well as taking a stage in the Tour of Spain. He was crowned both British Time Trial and Road-Race National Champion in 2017, the first rider to ‘do the double’ since Tour de France star David Millar ten years earlier. Recently retired, he is now development director at Ineos Grenadiers.

Alasdair Fotheringham is a British journalist writing mainly on cycling, Spain and Americana music. Based in Spain for the last 30 years, he is a freelance foreign correspondent for The Times and Al Jazeera and on cycling for the ‘I’ newspaper and Cyclingnews. Apart from covering the Tour de France since 1992, he has written four books, including the first English-language biographies of cycling’s greatest ever mountain climber, Federico Martín Bahamontes, aka The Eagle of Toledo, as well as a history of the 1998 Tour de France. Alasdair first met and interviewed Steve during the Spring Classics races of 2007, somewhere in darkest west Flanders.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Allen & Unwin,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Steve Cummings, 2022

The moral right of Steve Cummings to be identified as the authorof this work has been asserted by him in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or byany means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, orotherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyrightowner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectifyany mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 391 1

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 392 8

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.allenandunwin.com/uk

To my mum, Lesley. I’m eternally grateful for everything. You encouraged us but didn’t pressure us. You supported us but didn’t let us forget our roots. You dedicated your life to helping us grow. Every day is a blessing thanks to you. I will continue to try and improve day by day. Thank you for all the wonderful memories. See you soon.

Contents

Foreword: Geraint Thomas

Preface: The Landmark That Wasn’t

1 Doughnuts

2 Dilemmas

3 Contrasts

4 2008–09: Road or Track?

5 Man on a Mission

6 The Wrong Kind of Limits: Team Sky 2010–11

7 No Stress Man

8 Roller Coaster

9 A Human Time Bomb

10 Mandela Day

11 Why I Couldn’t Train with Mark Cavendish

12 The Right Direction

13 A Race Against Time

14 Back to My Roots

15 Bottles, Britain and a New Beginning

Nine Lessons

Palmarès

Plate Section: Photography Credits

Acknowledgements

Index

Foreword

Geraint Thomas

When I first met Steve, I was definitely nervous.

The first time I’d come across him was reading about him in Cycling Weekly when he’d won the Eddie Soens as a junior. That was impressive enough. Then he and Brad Wiggins were about five or six years older than me and what they were doing, road racing and track racing and World Championships and so on, they were the things I wanted to do in my career.

On top of that, when we actually met face to face the first time, I had just moved into the GB senior track team pursuit squad, and even though he was one of the younger blokes in it, Steve was already one of the leaders and driving forces. He was hungry for it – you could just see that in him – and I really admired him and wanted to have the same attitude.

At the same time, I was definitely nervous – not just because of what he’d done as a racer; it was him being a Scouser as well, and you’d hear stories about them too! Seriously, though, when I joined the group, to my relief I found he was very approachable. At the same time, no matter what it was, Steve always had this attitude: ‘I’m doing all this to be successful; why aren’t you?’

Steve wanted everyone around him to have that same outlook and when they couldn’t manage to do that, he struggled with it a bit. In team pursuit you’re reliant on the other guys to be as professional and as good as you, and that goes from everybody rolling out on time together on group training rides to being 100 per cent committed to the racing. Yet he was super-determined and wanted to do everything right too, and fortunately I was of a similar mentality so I ended up being quite close to him.

I think where we had our best times together was at Quarrata in 2008 or so, when we were racing for the same team, Barloworld, on the road, but I was focused on the track and the Olympics too. It was all part of a learning process to be a good road racer, but at the same time I was more of a track rider and the road was more of a tool to get fit for that.

There was a good group of us sharing the flat and then meeting with everybody in the piazza in Quarrata for a coffee before training. It was a nice lifestyle, and serious too; if we had to do five hours’ training, more often than not we’d do five and a half or six. Then in the second part of my time there, it was harder for me, because I’d been part of the British Cycling Academy and suddenly I found I didn’t have the support every day which I’d been used to. I was out there doing it alone. But while I was young and single at that point, Steve was there with Nicky and they really looked after me, cooking me food and so on. In that way, Steve is a very caring guy and having them both around was just what I needed.

In the two years he spent at Sky, the situation was new for them but obviously everybody at the top, be it Dave Brailsford or Rod Ellingworth or Tim Kerrison or Shane Sutton, had Brad as their main concern. I think Steve would probably have felt, ‘Hang on, there are another twenty-five guys in the team too.’ Everybody got dragged a bit into doing the same as what Brad was doing, and that probably wound Steve up.

The main thing I recollect at Sky was seeing him getting pulled this way and that way, while he’s someone who likes to have his plan and go full bore on it. And when that gets chopped and changed five or six times within a few weeks, that’s frustrating – and Steve was asking why it was happening.

Fortunately, there was a golden period for him later on, because there were two or three years where everything clicked for him and there was a time you’d go, ‘Ah, today’s a breakaway day; Steve’s going to win.’ And he would go and just win, stage after stage and then the Tour of Britain on top of that. It was great to see him get the recognition and success he deserved, because I knew he’d worked so hard and was so determined to get there.

Now having him at Ineos has worked out very well for me, because – like I’m writing here – I’ve grown up with him as a racer. He’s somebody who’s been in the peloton with me ever since I started and he’s someone I can talk to about anything on my mind, not just the bike racing.

If you wanted me to pinpoint the main reason why Steve succeeded, it’s the way he sees bike racing, his willingness to try something new, to do something differently. Those are his strongest characteristics even though I think that might have been a problem too when he was younger. He was maybe overthinking things and working out how to deal with that.

But then when it all clicked for him, he’d learned to use his gifts in the right way. There are so many guys out there who are strong, but Steve didn’t just have the legs, he had the brains and the head for it all as well and that was his big advantage. Ever since I first met him, in fact, Steve has always being thinking outside the box.

Preface

The Landmark That Wasn’t

I’ve always liked breaks in bike races. For what they are, visually, for one thing, but also for how they’re created. There’s something about a rider winning alone and ahead of the main field that always looks good. But it feels good as well. You know it’s been born out of strength, for one thing, but there are tactics, foresight, experience and race-reading ability as well. Some more, some less, but they all count, they all contribute, and they all make that kind of winning even more special. At the same time you know a breakaway victory is always a win against the odds, one for the underdog. So it appeals to the romantic in me as well.

To be honest, what I also liked about them was that from a very young age, I was very good at getting into breaks too, either alone or with others. The only problem was I didn’t really have the kind of perspective to appreciate how good I was.

For example, for many people, the first time I took a landmark, trademark breakaway solo win was when I raced the Eddie Soens Memorial Race in Liverpool in 1999. It was a handicap race ridden round laps of Aintree racecourse: it was open to all categories, one of the first events of the British cycling season and traditionally one of the biggest as well.

Growing up on the Wirral, there was no escaping that race if you wanted to show how good you were. It didn’t matter that I was only seventeen. Or that I had never ridden it before. People in the Merseyside area and down at the Eureka cafe – a local Mecca for cyclists that’s sadly closed down now – were always saying, ‘Oh, you’re doing the Soens?’ ‘I’m sure you’re doing the Soens,’ ‘You’ll be doing the Soens, yeah?’ So that was it, then, as soon as I was old enough, it was, ‘OK, whatever, I’m doing the Soens.’

The weather on the day was terrible. Five degrees and rain. But there was still a good crowd gathered round the finish, maybe up to a hundred or so. I wasn’t nervous beforehand, I was looking forward to it. After all, it was my first race of the year. My dad came and drove me over in the car, but he wasn’t normally overly pushy or expectant about races and the Soens that year wasn’t an exception. To be honest, I don’t think I’d have listened to what he’d have said anyway – truthfully, does anyone ever listen to their dad? He preferred to be practical and put me in touch with good people that he thought might be able to help me. But when I got out on to the course, in any case, it didn’t matter who backed me or supported me; I knew I was doing this on my own.

The key move happened when I got into a break of four with my regular training partner, Mark Baker, which was part of the plan we’d created beforehand about dropping all the older guys and getting ahead of the field. But then there was another lad from Preston, Iain Armstrong, who wasn’t in on the plan but who was fine with us two because he’d been up there in the same race the previous year and he knew what he was doing.

However, the man who definitely wasn’t part of the plan in the break was Phil Bayton, a real star veteran, the ‘Staffordshire Engine’ as he was known. Being a mouthy, punky sort of rider I kept on saying to him, ‘Fucking hell, come through and give us a turn,’ – riding on the front of the break or peloton to keep the pace going and allow the other riders to rest a little from their effort in your slipstream – which was more than a bit disrespectful to one of GB’s cycling heroes of the era. But at the time, in my defence, I was so new to the scene I had no idea who he actually was.

Then respect due or no respect due, I dropped them all. I did the last three laps of the Eddie Soens on my own. I don’t think I ever really jumped away. I just killed them, one by one. But as I rode towards victory, for lap after lap, rather than savouring this as the glorious start to my budding career as a breakaway specialist, was I thinking, ‘This is something special’ or ‘At your age it doesn’t get bigger than this’ or even ‘Treasure it, mate, well done’?

No. I was thinking about how many Bosswipes I’d be taking home.

Bosswipes were (and are) good for cleaning your bike – they’re like industrial baby wipes but stronger – and that year in the Soens, the company that made Bosswipes were sponsoring the primes, the prizes that were on offer for leading the race at different points of the event. And I was quite greedy when we were in our break. I wanted to win all of the primes. No mercy. No gifts.

So after I’d won, I remember feeling rich, because I’d made £100 or £200 or whatever. But I remember feeling particularly pleased that we drove away with my dad’s car packed to the ceiling with Bosswipes. Two different types, boxes as big as a breakfast cereal packet, and a huge tub of Bosswipe gel cleaner for your hands, which lasted me for years.

And the win itself? People at the Eureka used to harp on about the Soens for months and how much it mattered like it was the World Cup final or something, but at the time to me it seemed insignificant. Plus I had this thing at the time that if I did something good, I’d put it behind me straight away and move on to the next objective.

The problem was, fundamentally, I don’t think I was rounded enough as a person at that time to appreciate what I’d achieved. Which was a pity because my next win on the road, as a professional, took the best part of a decade to happen. And my first Grand Tour stage win took nearly another five years after that.

What those victories have in common, of course, with the one at the Soens is that my wins were nearly all taken from breakaways – often on the so-called ‘transition’ or ‘medium-mountain’ stages. These are the days in a race when the battle for the overall win is put on hold because the terrain is challenging, but not quite hard enough for the big names to risk attacking and losing more than they gain in the process. These kinds of stages are the best days for the outsiders in the peloton, to shine in breaks. They’re days for the nonconformists and for the dark horses. For the guys, like me, who were pretty good at everything but with no standout talent, and yet who were determined to keep thinking outside the box until we did win. Because we don’t – with no disrespect intended – simply settle for working for a team leader as the be-all and end-all of their career, rather we know we can never go for the win in the Tour de France. But we do want our own share of the glory all the same.

At this point I should make it clear that no two breakaway specialists use exactly the same strategies for winning. Some, like one of Germany’s former top racers, Jens Voigt, apparently do it almost purely through driving themselves through their pain barriers and hurting themselves: if he was famous for that phrase of his, ‘Shut up, legs’, surely must have been for a reason.

But I wasn’t like that, I wanted to win by maximizing my performance in all areas, not just going into the hurt locker deeper than anyone else. You could say I was trying to race with my brain and not my legs. But to do that, to get from the Soens at Aintree racecourse to becoming one of the international peloton’s best-known riders for getting in breakaways (and winning, which is the hard part), took a lot of hard thinking and a lot of trial and error, a lot of finding out what I didn’t want too, as well as hard graft. Until – finally – I paved a way forward that brought me success not just occasionally, but in race after race.

And because it wasn’t all about pain, the lessons I learned in those twenty years can be applied not only in cycling, but in all walks of life. What I want to show in this book is how being a top breakaway specialist can help normal people succeed. Because it’s about making the best of your abilities and how to focus on seizing your opportunity when it comes.

You might even win a few Bosswipes while you’re at it too.

Chapter 1

Doughnuts

Maybe it was to do with growing up on the Wirral in a working-class family, or maybe it was my own personality, but one of the key lessons cycling has taught me is that if you look hard enough, the most unexpected raw materials can help you attain your objective. Like, for example, doughnuts.

This happened just before I won the Soens, when I was seventeen, and I had Mark Baker as my regular training partner. Mark was ideal in some ways as he was an extremely good racer in GB’s National Road squad. But on the downside, his dad bought him all the flash kit right down to the Oakley glasses and Carnac shoes, the works, and every time he said, ‘Steve, why don’t you get these new tyres?’ I had to admit I felt peer pressure. The thing was I was only earning £8 a week on a paper round, which really wasn’t the kind of money that would get me that kind of high-end equipment.

So I put my thinking cap on and hit on the scheme of selling doughnuts at school. And it worked out really well. I’d get a first paper round done super-early, then I’d do a second one, then just before school I’d go to Tesco, where at the time you could buy ten jam doughnuts for a pound. I’d buy fifty doughnuts, sometimes seventy, and by selling them for 20p each I’d make £7 a day. Put together with the money from my two paper rounds, it all went on getting better cycling equipment.

It was never quite enough. If Mark had Oakleys, I’d still have to settle for the Brikos, a cheaper kind. On top of which he’d started racing earlier than me and his bike was lighter than mine. But thanks to Tesco’s doughnuts, when we both got away in the Soens in the winning break that year, the playing field was a lot more level.

It was the same kind of DIY initiative that helped me to my breakthrough win at the ‘schoolboy’ category, aged fifteen, when I won one of that level’s biggest one-day races, the GHS 10 Mile individual time trial. I was riding on a bike that had been put together starting from, literally, nothing. Based entirely on parts begged, borrowed and not quite stolen from friends, the construction process consisted of, ‘Oh, we’ve got this bit, let’s put this bit on to this,’ and ‘Then we can add this,’ and ‘Then we can add this.’ The part of the process that nearly defeated us was trying to fit the crank on to the bottom bracket. So we went round to my trainer at the time, Keith Boardman – and that name should ring a bell with most readers, or at least his son Chris should do – and we cut up a Coke can and made a kind of shim around the bottom bracket axle. Then I put the crank on to make the axle wider, and we drove south to wherever the race was held, with me down to compete using a bike which actually moved thanks to a fixed wheel with an old tri spoke that had belonged to Chris at some stage and a rear disc wheel on loan from The Bike Factory. Somehow, utterly improbably, we had created the bike though, and I ended up winning the GHS Schoolboy 10 Mile Time Trial on it too.

Being resourceful with what you had at your disposal was one area I realized I had to get good in if I wanted to be a good cyclist. Another life lesson was learning about how to turn things you didn’t like into something beneficial. I hated school, for example, and wasn’t a good student, so I’d try to bunk off as many lessons as I could to ride my bike. Particularly religious education.

After I’d won the Schoolboy 10 I think the teachers realized I was doing something relatively productive compared to the rest of the kids playing truant. So I realized that was the perfect moment to have some off-the-record discussions with them, and rather than getting myself thrown out of RE class by making trouble, from then on I knew some teachers would turn a blind eye if I disappeared early on Tuesday afternoons to go ride my bike before it got too dark.

But there’s only so much you can do for yourself at that age, of course. I wouldn’t have won that Schoolboy 10, for example, if it hadn’t been for a kind-hearted big guy we knew locally as Stevie Light. Stevie wasn’t a bike rider, but he just liked cycling and he was good enough to drive me and Mark to races. Others I’d like to thank here and now include Alison France, Jack McAllister (more on those two later), Stan Moly, Danny MacD, Tempo, Big Kev, Chubbie, Woodsie, Bobby Mac, Keith and Carol, Mike and Pat… it’s a long list! Key to my progress in cycling, though, were my mum and dad, who although there wasn’t any history of major sport in the family, both always thought lots of cycling as a hobby.

My dad, Dave, who was a policeman in Liverpool, where they’re both from, was a bit nuts about sport himself. He’d run to work and then ride home. My mum, our Les, was really into running too. She did a marathon when she was forty in under four hours and she was holding down a full-time job as an NHS receptionist as well. For me as a kid, football and cycling were the two things I liked the most. But my individualism started coming out pretty early on, and I left off football even though I loved it – and still do – because I sort of felt I was overly reliant on the team and couldn’t control the way things played out if it was you and ten other guys on the pitch. For me, that was frustrating. Plus I wasn’t good enough.

At the same time, when I was a little kid I was always riding my bike, round and round the block on the housing estate where we lived in Pensby on the Wirral. I must admit, though, that the 1992 Olympics, when Chris Boardman had his breakthrough by winning gold, it went completely over my head. But I liked the freedom cycling gave you regardless, and when I got older, the way it got me to places I’d never been to before like Delamere Forest, the Cheshire Plain, sometimes a bit of North Wales. Then there was the bit of banter with the other guys on the training rides too.

At first, when I was eleven, they wouldn’t let me sign up for Birkenhead North End cycling club because they weren’t insured for kids. But we got round it through my dad joining. Even before that I’d go out with my dad and my elder brother and his mates out from home in Pensby along the Chester High Road – which you wouldn’t dream of doing now as it’s way too dangerous – to the Eureka cafe. I remember the first time I did that I probably only rode eight miles in total and I fell off on the way home and cut my knee because I was so fucked, but I didn’t care. I loved what I was doing.

There was a bit of racing right from the start in my club, when we’d meet up on a Thursday at the community centre, have a cup of tea then go on a club run which normally involved either racing for town signs or riding to a climb, which most or all of us would race up as well. But what really got me into competitive cycling were our camping holidays in France when I was a teenager. I remember how everyone on the campsite would be sitting round drinking beers in their tank tops in some dodgy bar and watching the Tour de France. At that age it felt like not only the whole of France was watching, but all the Dutch and Belgian tourists were too – everybody in the rest of Europe in fact. I didn’t understand the race, but I wanted to understand why all these people were drawn to it, and that way the Tour and road racing got under my skin.

My dad was really encouraging about it all, given I was so committed. He even helped me avoid certain classes at school to go riding, so if I said to him, ‘Dad, I’ve got Spanish today,’ and in fact I’d go out on my bike, he’d turn a blind eye. My mum kind of knew that I was not a good pupil, but as she was always at work throughout the day, it wasn’t such a big deal. My dad, though, worked shifts, and sometimes I’d get his shift wrong, come home from school early and he’d be sitting there on the sofa, asking me what I was doing. But it was fine. I’d say I was going out on my bike and he’d say, ‘Don’t tell your mother,’ and we’d leave it at that.

Dad used to take me down to the cycling club as well in the community centre, which was where all my mates and a few other people I’d know would go and drink and smoke weed outside. Being very glad it was usually dark when club night got under way, I’d try to avoid being seen by my mates going in. But I couldn’t dodge a few embarrassing moments when the old guys in the club would be slagging off ‘those bloody scallies’ who had lit fires outside the fire escape door, and I knew exactly who the bloody scallies were.

There weren’t many young people at the time doing cycling. Sometimes you’d go down to Pensby Park on a Thursday evening and there’d maybe be only five or six riders actually there for racing. But I had the backing of my parents, there was the crowd at the club and the Eureka cafe that I’d go racing and riding with as well, and people from other clubs like Port Sunlight Wheelers were very supportive too.

Up until I was thirteen or fourteen, I’d been on a mountain bike, working my way through the sizes. One high point of that time was getting a really good one, a Diamondback, which I managed to blag my father into buying for me and I cannot for the life of me remember how I convinced him. But there was one guy, Jack McAllister, who’d only met me once at the club but straight away he lent me his wife’s bike to be my first proper road bike, which I used through the winter while I saved up to buy my own. There were a lot of good-hearted people there too, like Jack, who’d take responsibility for me on the training rides because my dad couldn’t get out. Or Alison France, who helped with expenses, while somebody else would provide petrol money. I was really fortunate to have these people around me, and at places like the Eureka, I had a place where I fitted in.

This was very different to school where they might have turned a blind eye to my playing truant, but until I won that Schoolboy 10 race I’d have to tell everybody my age I was going to be a boxer to stop the other dropouts asking me why I wasn’t smoking dope and drinking like they were.

Then by the time I hit sixteen, I really committed to working with Keith Boardman and I’d go out training three or four times a week, twice at weekends. One day off a week and that was it. I used to listen a lot to Keith – he talked a lot of sense – and you couldn’t help but think that he had to be right because of the way Chris had progressed. On top of that he definitely liked a plan and everything had to be objective-driven, so if we were going to do something it had to have a purpose. One slight issue was that Keith was always trying to get me to do more time trialling – Chris’s speciality on the road – but even at that age, although I could see how beneficial time trialling was, I wasn’t so keen on it. Riding up and down a dual carriageway by myself, as you did so often in time trials back then, didn’t appeal to me that much. And some people love the equipment side of it, but to me the idea of being able to make a difference through aerodynamics when I didn’t have a big budget didn’t appeal either. Finally, at that time, I liked being in company when I rode my bike. So we eventually reached an agreement that every road race I did, I’d do a time trial as well and we went on working together, which was great.

Obviously, being from the Wirral and with Keith as my trainer, I knew Chris at the time too, but I didn’t go out riding with him much because he obsessed with getting every tiny detail right and although I completely get that now, at the time, as a teenager, it wasn’t much fun. When I did go out training with him, he was scarily serious. You’d tell a joke to break the ice early on and he wouldn’t laugh, and then you’d think, ‘Fucking hell, we’ve got four hours riding ahead of us here, Chris.’ So although I had and have huge respect for what he’d done, it wasn’t a tremendously appealing prospect.

I was always grateful to get a chance to talk to the pros though. I remember after the Soens win, when I got into the GB Junior team, another star of the 1980s and 1990s, Robert Millar (now Philippa York), came out to a training camp we had organized for us in Spain and I had a chat with him during a training ride. It was so rare for us to be able to get to talk to pros at that time that any information at all about what it was like in that world was like gold dust.

Another pro I came across early on was Max Sciandri, who is half-Italian and half-British. Max was going to become a very close friend, but when I first met him, at the Junior World Championships in Verona in 1999 when he was with FDJ, I was just star-struck. We were all sitting round a table having dinner and he’d just come in from racing one of France’s biggest races, Paris–Tours. We were nudging each other and saying, ‘Oh my God, it’s Max Sciandri,’ and he came over, sat down and said, ‘Hey, how’s it going, guys?’ I was so nervous I was sweating! But he had a really friendly way of doing things: ‘How long did you guys ride today?’; ‘Hey, I went and did the climb, it’s nice.’ Even if I remember at that time his English wasn’t great – ‘What do you call those little pies again that taste of nothing? Oh, yeah, York-s-hire [pronounced Max-style with three syllables] pies’ – it meant the world to me to have just had even a brief contact with him. But I didn’t see him for ages after that, until he started working again for British Cycling and helping them place riders, like me, in pro teams.

Apart from riding under Keith’s tuition, I was broadening my talents in other ways: I started going up to Kirkby Track League up on the far side of Liverpool and that was a scream. The journey itself was always fun, four of us driving up there as we were crammed into this small van with only two seats. So there’d be two of us in the back along with the bikes, slamming around on the corners of the Mersey Tunnel, which is quite twisty. There were some real characters around like Pete and Lee Matthews, and I loved the racing: we did everything – points, Devils… we had different groups too, A, B and C, depending on how you were performing. Normally, if you were a junior you’d be in with the Bs, but I was good enough for the commissaires to put me in with the As. However, they’d never call you by name. It’d be ‘You’re in group A, rider,’ or ‘Watch your line, rider.’ Odd, but I didn’t mind.

Then if the weather was bad at the weekend, and I couldn’t get out on the road, I would head over to Manchester track with Graham Weigh, a big cycling fan who has one of the biggest bike shops in North Wales just over the border from the Wirral, and where I did a bit of work. I’d do the drop-in induction sessions at the Manchester track centre and that was where I got an invite to the National Team Junior training session from Marshall Thomas, the guy running them at the time. That quickly got me an invite to the National Track Championships as a first-year junior, where I did the points race, with Bradley Wiggins as my biggest rival. Apart from being a year older than me, performance-wise Bradley was on another planet. But I qualified for the individual pursuit as well, so I was very quickly moving through the levels.

I’d got one big road win apart from the Soens in the bag too in 1999, when I took the Junior National Road Race. More than the victory in itself, I was proud of how I won, just riding off on my own again, and it made me think about what I could maybe do in the future. But I still couldn’t believe that I could make money out of something I enjoyed so much.

Still, I looked at what that junior title meant I could do, which was to put me in the circle of British junior racers who could get away to race abroad. I wanted to move on and see what was next. And while it opened quite a few doors, I was still quite intermittent in terms of results, so I didn’t develop a big ego from winning it. In the time trials for one thing, there was always Brad Wiggins who was always three minutes faster than me. That always helped put things in perspective.

Chapter 2

Dilemmas

Around this time my formal education experience was petering out. I’d managed to get out of my school in Pensby – it wasn’t exactly full of drug dealers, but the teaching was far from great – and I went to work in a restaurant on the Wirral as a dishwasher. Academically, I was borderline although I did briefly manage to get into a good sixth-form college, at Calday, partly because I’d won the Schoolboy 10 race and they wanted some promising athletes, and partly because Mum had contacts. But although I was doing business studies, sports studies and maths there – and these three subjects I still like – it was a really affluent area and I didn’t feel I fitted in. To make matters even worse, I got glandular fever and that set me back almost a year, so I went to work in a restaurant instead all the way through to the spring of 2001.

Ever since 1999 and the wins in the Soens and Nationals, apart from being on the GB Track squad, I’d been part of the GB Junior National Road team too. The only problem at that point was that it was run on a shoestring, and you’d barely get a jersey if you were part of it. You couldn’t fault some of the staff though for trying their utmost and keeping our feet on the ground. Mike Taylor, the Junior National coach, was one guy I remember for being great as a trainer. He was a charming, wonderful person but he was fantastically straight-talking too, and after I’d won the Soens he’d take the piss out of me: ‘So you think you’re a superstar, now?’ And I remember him calling another GB trainer ‘about as much use as a fucking chocolate fireguard’. Mike had worked with top British cycling names like David Millar, John Herety and Charly Wegelius, and he’d tell funny stories about them, which kept us interested too. As a person he amused me, by doing things like happily swearing away if we were talking in the team, but abruptly stopping whenever anybody’s parents turned up.

Blessed with a strong anti-establishment outlook (which I also appreciated), Mike was honest enough to recognize that as we were operating with such a tiny budget, that meant we had to keep our options open. Apart from the restaurant work, my other business in those days was selling cigarettes when we went to France for race trips. So Mike would say on the Channel ferry when he saw me, ‘What the fucking hell are you doing buying 1000 cigarettes; are you smoking?’ and I’d say, ‘No, no, I sell them,’ to which he’d say, ‘Right, we’ll buy some fucking more then – come on.’

Cycling had, indirectly, introduced me to my future wife Nicky too. Her boss at her place of work was in our cycling club and his son was a year younger than me so we all used to go riding a lot. Then I’d go into their shop a lot as well and ‘run into’ Nicky. She used to swim at county level competitions, so she understood sport, which helped ease things along. At first I’d just joke around, asking when she’d come on a date with me and how ‘you should get rid of that boyfriend of yours.’ And eventually she did get rid of him and started going out with me.

I wanted to be on my bike and pretty much nothing else, and I’d started working hard in the restaurant, doing more than twenty-five hours a week there as well. I’d start training at 7 a.m. then ride straight to the restaurant, grab lunch and eat while doing the vegetables and then head off to the gym afterwards. It was a great time in some ways as the chef and I got on very well and we’d be listening to rap like 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G. all day. But as Christmas 2000 approached it got pretty crazy. I was helping the chef doing overtime and ended up doing fourteen-hour shifts, before which I’d been on my bike. So I was quite relieved when I finally quit in March 2001 and concentrated fully on racing instead.

Could I have gone straight on to the road and left the track behind at that point? Possibly, but at the time you didn’t have that many British pros out there – Chris had just retired and Sean Yates and Robert Millar had long gone, so there was only David Millar, Roger Hammond and Jeremy Hunt at the top level. It didn’t feel like a realistic option. I didn’t know the people to contact or the best way to go about it, and probably I just wasn’t proactive enough either.

I’d also been drawn into the structure that GB track racing seemed to offer so clearly. I’d got used to that structured approach with Keith, but I’d stopped working with him because he thought he’d done all he could to help me. But things gradually got harder with the track too, because I never found anyone to take over Keith’s role until I came across Simon Jones and Steve Peters, and that gap meant that when I went from Junior to Under-23 in 2000, suddenly I got into a real mess. After years of moving forwards, albeit patchily, I found that I didn’t have that sense of direction I so badly needed.

I’d be lying if I wrote that for the first two decades of my life I knew that I was definitely going to be a racing cyclist. But I’d be lying too if I didn’t admit I really needed help to work out how much I wanted to buy into track racing and how much I wanted to buy into road racing.

That help didn’t really arrive for another four years. So it was just as well I wasn’t going off the rails completely. It was more when I hit twenty I had got a bit lost and just did what my mates were doing. My elder brother, who’d left home first, was looking after a pub, which didn’t help, as after going out on the bike, I’d go down to the pub myself.

But after the Antwerp World Championships, when GB offered me some regular funding and things got more serious, in the autumn of 2001 I moved on myself. Things were not easy at home at that point, and my two brothers and I were a handful to say the least. This made things hard to say the least for my mum and dad and at times I wanted to be anywhere else but there. I needed to figure out how to get out.

Fortunately, that opportunity came, thanks to the track. I had got as far as the GB senior team pursuit squad that year, when I first started training with them, but up to that point cycling still almost felt like a hobby. Even getting into the seniors hadn’t seemed like a massive deal, as somebody had said, ‘He’s doing all right, let’s put him in.’ But after I’d been working in a kitchen doing dishes, it was something to enjoy, particularly as the World Class Performance Plan, which later transformed British Cycling, was still in its infancy. It hadn’t been that long, in fact, since people were still doing full-time ‘day jobs’ to be part of the national team. The competition to get into the team was fierce, but there weren’t so many people and the level wasn’t amazing. Suddenly, though, when Dave Brailsford got a much bigger role in the GB team and Simon Jones took over in the track programme, the whole track programme moved up a gear and, out of nowhere, it became a career option.

There were catches. The management knew I was a bit of a lad so they said the only way they’d give me the funding on the GB track programme was if I moved up to Manchester, which meant I lived with Paul Manning in Stockport for six months. When I was with them I was 100 per cent committed, and Nicky used to drive up to Stockport once or twice a week, and because of her things started to settle down more as well.

I talked it over with Simon Jones and Nicky and we moved back to the Wirral and rented a place in Moreton – though we then saved up a bit of money and that later got us a down payment on a house in a nicer part of the Wirral, in Irby.

I’d also had a brutal wake-up call about the effects of alcohol. Another guy I’d train with, Mark Bell, was really strong as a racer, but at that time he had a drink problem so you’d not see him for a week or a month at a time. During the Commonwealth Games in Manchester in 2002 I went to his flat, and it was in an awful mess. That really planted a seed in my head about drinking and I basically stopped then. It got to the point where I had to stop seeing Mark too. I didn’t want to do that, but he’d got into a vicious circle and I couldn’t do anything more for him. Besides, I was heading towards my own personal moment of crisis too.

*

One morning in 2004, British Cycling boss Dave Brailsford summoned me into his office at the Manchester Track Centre, sat me down and gave it to me straight: ‘The problem I have with you,’ he said, ‘is I can’t figure you out. When you want you’re the best rider out there we’ve got, but I don’t see it enough. I need you to be consistent. I need you to buy in.’

I didn’t know what to answer. At that time, my cycling life consisted mainly of racing regularly all year with Britain’s senior team pursuit track squad and I had been doing that since 2000. But inside myself, I didn’t have any sense of direction, and it didn’t help either that when that conversation happened, I had just lost three people I was quite close to in a very short period of time. My grandmother had died and then Dan Baird, a young friend of mine who lived up the road, died, and that was a big shock. Finally, a good friend of my dad’s, Doug Phillips, a really special guy who used to go to the track, died too. It was very tough because they all meant a lot to me.

My personal crisis had got to the point where I had been in France on a road race that year – something we did as a way of building up our resistance, or endurance as it’s known in cycling, for our track racing – and rather than strengthening my resistance, somewhere in the middle of the event I had broken down and started crying. Basically, I hated it all.

*

How did I get out of this situation and move on? Probably the biggest element to all of my moving ahead was what I learned from Steve Peters, who was working with British Cycling as a psychologist, even though he’d trained as a psychiatrist. Just when I had lost the plot and had had that conversation with Dave Brailsford about buying in, Steve came into the velodrome in Manchester and began sitting me down for chats. And apart from helping me get over the people I’d lost, he also helped me enormously with what was essentially a fear of failure.

Up until then, I’d never really committed to anything on the track, because no matter what, when I say I’ll commit to something I’ll do it. So when Steve asked what my biggest fear was, I said ‘that I wouldn’t be able to do it’. But over the course of several sessions, he gently outlined to me that if I didn’t try, then I’d never be able to get there. That was like a switch that flicked to ‘on’. After that, every time my leg went over the bike I was determined to give it 100 per cent. There was no more fucking around.

In fact, I went to the opposite extreme. I then became so scared of not getting the best out of myself, it was like I was on a mission. Failure is defined as not being able to do something, but after my work with Steve I didn’t care if I could do it or not. All I cared about was getting the best out of myself; I had to do that, and if I failed, I failed. But if that was good enough, then great.

Steve worked closely alongside Brailsford, of course, who also kept tabs on me. Dave told me I was to ring him every Monday morning at 9 a.m. and tell him what was going on, how I was, what I’d been up to. Not just training, everything.

But I didn’t actually need to call Dave. From that point on, I drove myself so hard and it was so fucking intense that at times it was ridiculous.

Imagine your degree of commitment to something as a kind of continuum, where one end of it is a completely intense, obsessive attitude, and the other is you’re not buying it at all or doing anything – you don’t give a fuck. The first key to anything consistent, like Dave wanted me to be, is to find whatever is sustainable, the right balance for varying periods of time, depending on the objective, and in a way that meant I stayed happy. So I would go right to the obsessive end of the continuum, take the fewest of a few steps back and boom! That’s what’s became sustainable for me.

As I stepped up our game and I became a senior member of the squad, I grew much harsher and demanding with everybody, including myself. I developed the same attitude that the most dedicated racers have, guys like Rohan Dennis, the former World Time Trial Champion. If somebody’s not as committed as he is, Rohan gets very upset about every single question, such as the famous occasion when it wasn’t clear if the right skinsuit for his TT was available.

I was intense. I used to call my team-mates out. Like Rohan I had legitimate frustrations at times, but they’d overspill and came out in ways that weren’t effective at getting results, like questioning their commitment. But it was partly because my communication skills weren’t great at the time, and partly that you know young guys come in thinking it’s an adventure or a bit of a joke, and I wanted to try to get them to see how much I was relying on them and we, the team, needed them. We’d worked exceptionally hard at getting it right and the squad had got bronze in Sydney’s Olympics, and then we got silver in Athens in 2004, but we kept on getting stuck on silver, silver, silver, pretty much always to the Australians. The whole question was, what more did we need to do?

*

On paper, the team pursuit looks pretty straightforward. Four people in each team line up on opposite sides of the track; they race each other for 4 kilometres in a single line, and the first team to get three of its riders to complete the distance is the one that wins. But in fact, it’s so simple that no detail can be overlooked, from the speed that you start, to following your team-mate’s back wheel at exactly the right distance, through to getting your changeovers and the communication between all four of you to be as smooth and effective as possible. You have to be incredibly concentrated, particularly as it’s the fastest endurance event in track racing and you know the smallest error can blow it all apart.

The velodrome itself is key too, because – for example – on every track there’s always a slightly different point where it’s best to do your changeover, and it is only with time where you feel where it is and can be sure that your changeovers are in tune with the nature of the boards. There are lots of advantages to getting your changeovers right, but one is you’re not dropping into the line again in the straightaways. Instead, using the steepest points, you’re flung back down where you want to be thanks to gravity and don’t have to accelerate to regain contact with the line.

Getting back in is crucial too, and that changes a lot with each track. In Manchester, say, where you’re so used to that, it’s automatic, and in any case it is a lovely big bowl. But some tracks have such long straightaways, it almost feels like you’re going uphill in the middle and your cadence can drop off quite a lot. And the banking is so tight, you get flung round really hard.

A key point of a good change in a team pursuit is what’s called ‘delivery’, which is how you get out of the front of the line and away from the team. In my mind, the last three pedal strokes before you do that are critical and that’s when you really have to push away from the team, giving them a positive momentum. But if you’re slowing up at the end of your effort, just before you do that push-away, then that has an opposite knock-on effect down the line, and then suddenly all the team is backing up, which is a disaster.

Then when you move out of the line, it is all about being able to produce a smooth arc as you do so. If you go up and down too fast, then you can scrub your speed off, and while doing it smoothly looks like a little bit of showboating – Bradley’s very good at it – you do keep that momentum.

There are ways of checking each rider’s delivery style: time splits on the turns each rider takes sometimes partly expose that positive or negative effect. Say somebody will do 14.4 seconds but then somebody will do 14.9 seconds, that’s a huge difference, because you want an evenly timed split. However, it could perfectly well be that the third guy does an amazing turn of 14.5 seconds and ‘redelivers’ the team successfully again. But if we wanted to get that right, we found the best way was by putting timing devices at every ten metres around the track and that gave us the full profile of what was happening on each lap for each rider. (For the record the main riders at the time – 2003 or so – were Paul Manning, Chris Newton, Bryan Steel and me because Bradley and Rob Hayles were often off being road pros then, at FDJ and Cofidis.)

It was all painstakingly hard work. But it also shows how incredibly detailed an approach we took to try to improve, and with time we turned the changeovers in particular into an art form. Some things though we deliberately kept very simple, like communication between each rider, just yelling out ‘hold’ for hold your speed, or ‘change’ because you could feel the rider ahead was slowing down. Knowing what needed to be straightforward and what needed to be broken down into really detailed parts to make sure each bit worked right is one way of saying that it was all about the bigger picture. And in fact one of the most useful skills I learned through Steve Peters in that era was gaining perspective, as in ‘it’s only a bike race, no one’s going to die.’ When you’re young, it does feel like life and death, and that’s all you want to do, so that was particularly useful!

But Steve also helped with another technique called visualization, about what to do if you start to panic, and splitting the race into sections. My changeovers were already that practised that I could do them without thinking, and with the visualization, whenever I did a good one in training, I’d store it up and think, ‘That’s how I do it.’ At times it felt like there were a million other things to learn to handle, even if it was actually quite simple. You’d feel like you could be able to do another half lap, but then coming towards it, you might start thinking you were tying up. There was having to remember every time that your entire turn doesn’t finish when you swing out from the lead position, but when you rejoin the line. Thanks to Steve Peters, getting that sort of perspective and visualization on such techniques was really useful, because while there was a lot of sports science involved, it was always backed up with feelings.

It was never all about us, either. There was also the degree of crowd support: in Los Angeles, the crowds weren’t ever good there, while in places like Manchester and Australia in the Commonwealth Games they were great. Then at the Olympics in Athens, where I was part of the squad that took silver in the team pursuit, the velodrome design was really cool, because it was on the edge of the Olympic areas and it was open-sided. So at night in particular and for the finals everybody would come past and look and you felt like the world was watching.

But in terms of visualization that’s not such a big deal. You’re in the zone, you do your work and you come out. And at that point in my career, having got through my phase of nearly going off the rails then getting ultra-committed, I was definitely fast getting to a point of I’ve been there, bought the T-shirt, now let’s go and do something else.

*

Even in the final moments before a World Championships like Los Angeles in 2005, where we finally got that win we’d been looking for for so long, I didn’t have any special structure to my personal countdown before I got on the bike. As a track rider, the thinking was that you had to be really fresh when you started your race, something I’m still not convinced about, but which meant there was a lot of free time. So I basically would go around talking to people. Anybody. I didn’t want to sit in my room unless I deliberately wanted to sit there and think hard about the good changes, the good start… again, visualization. But then when that was done, I’d go and find anybody and have a chat and a bit of a laugh; just to keep my mind occupied.

Even when the final warm-up began and the ‘rules’ were simply visualize and don’t fuck around, sometimes I’d relax even a bit more that way and end up talking to soigneurs before we began our ride. It was all a long way from other people who’d absolutely have to do twenty minutes on the rollers in silence as their way of dealing with the pressure. You’d respect that, and you’d know you’d never talk to Bradley, for example, because he wouldn’t ever want to chat at all. But my way was five minutes on the rollers, put some chamois cream on if I had to and get a bottle, try to get a bit warm. I wasn’t that scientific – I was what I called ballpark scientific, which to me meant use the science, follow the outline of the proposed warm-up and in the last five minutes don’t talk to anybody because it’s a distraction, but don’t get preoccupied, stay very relaxed, and use your feelings as well. Above all, you have to look at it as just another effort, doing what you’d been trained to do. And with that outlook, at the end of the day it was all about going to see what you could do. There might have been a few fist bumps and talking ourselves up in the last minutes. But not much more.