11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

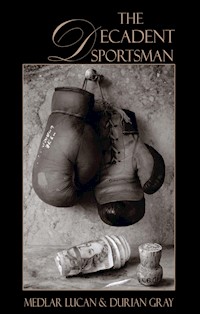

A decadent history of sport with an alternative olympic games. From their offices above a boxing gym in Old Havana, Medlar Lucan and Durian Gray have set aside their congenital lethargy to begin a glittering and fantastical new project: The Decadent Sportsman. "We are inspired in part by the magnificent wastefulness of the preparations for the London Olympic Games, exactly the kind of futile extravagance that Caligula or Nero would have adored, and in part by the pungent odours of sweat and bruised leather that waft up through the ventilation grillles in the floorboards from the boxing ring below." This orchid-scented duo bring their wit and monstrous imaginations to play across the entire history of sport, with chapters ranging from the Greek athletic ideal and its perversions to the Nazi Olympics of 1936 and the use of drugs, alcohol and visionary states of being. The book also includes the full text of their proposal to the IOC for a new and more impressive Alternative Olympic Games, with events such as voyeurism, dentistry, Russian roulette, cocktail mixing, posing, couture, hairdressing, mendacity, bohemianism, architectural patisserie, and the roasting and carving of meat.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

To Walter and Maria Schnepel

Artists, Patrons, Bearers of the Decadent Light

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We salute the noble souls who have helped us in the writing of this book: most particularly Piers Pottinger, William Martin, Sir Anthony Weldon, Tom Guest and Tony Ortega of The Village Voice.

We thank those authors, publishers and literary agents who have kindly granted us permission to quote from their works: Egidio Gavazzi (Desiderio di Volo), Nigel Spivey (The Ancient Olympics), Gustav Temple (The Chap Olympiad), Random House Publishers for W by Georges Perec and Waterlog by Roger Deakin, and David Godwin Associates for Haunts of the Black Masseur by Charles Sprawson.

We greet again all those – agents, publishers, authors – whom we have asked for permission to quote, but who have not found it possible to reply. Silence is tricky to interpret, but we take it as a sign of assent, and thank them in their absence. Those whom we have failed utterly to reach, we invite to contact our publisher, George (‘the Terminator’) Barrington, or, if you are passing through Havana, to drop in at El Periquito for a glass of rum. Señora Carmela, our patron and bankruptcy administrator, will be pleased to give you a memorable evening.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Quote

Foreword

Introduction: Mens insana in corpore immundo

1 The Fornicast

2 The Hydrophile

3 The Duellist

4 The Rider

5 The Gymnast

6 The Sculptor of Flesh

7 The Fighter

8 The New Olympian

9 Mind Games

Authors

Copyright

‘the human body, that exquisite engine of delights’

Norman Douglas, Siren Land

‘…in spite of the tennis the skull alas the stones…’

Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot

FOREWORD

His Excellency Oscar Luz Morada, Cuban Minister for Sport and Mental Health

In Cuba we take sport seriously. We won an honourable 16th position in the 2012 Olympics, ahead of Spain, South Africa, Mexico, Denmark, Poland, Fiji, Brazil and many other capitalist and imperialist powers. Our athletes are beautiful and strong. Their strength comes from the people. We cultivate the health and athletic skills of our workers, in accordance with the vision of our great Leader Fidel, who was himself a keen gymnast in his youth. In Cuba today all our children spend holidays in sport schools among orange and lemon groves on the Island of Youth. We have swimming pools and baseball stadiums. We have football fields. We have 19,000 boxers and many boxing rings. We send our trainers to work in more than 50 countries.

It is a privilege to have such distinguished personalities as Mr Lucan and Mr Gray sharing their love of sport and art with our people, especially our young people. These two gentlemen have left magnificent careers in England, deserted the fashionable salons of New York, Paris and Milan, and scorned the pages of high-society magazines – why? They do not say. But by their choice to live in Havana they show solidarity with the people of Cuba. They have made the Gimnaseo de Boxeo Guillermo Horta a headquarters of revolutionary artistic thought.

As Minister of Mental Health I must also pay tribute to Mr Lucan and Mr Gray for something else. By their example they have demonstrated that it is possible to live a deranged, eccentric, strangely sexed existence, yet still contribute to our society. The contribution is oblique. It is unusual. But it is real, for they bring hope and glamour to the world’s marginals, lunatics, freaks and oddballs – that estimable portion of the human race who feel that conformity is a prison, and who suffer the consequences.

I have read many pages of this beautiful book. I hope to read many more. I recommend it to all those who wish to be free. And to all those who wish to understand the corruption of the capitalist world and its much-vaunted spirit of competition, which leads inevitably to exploitation and slavery. Such criticism from within is more precious than diamonds. As the old Cuban saying goes, there are fifteen ways to make a cigar but only one way to smoke it.

Havana, 27 August 2012

INTRODUCTION: MENS INSANA IN CORPORE IMMUNDO

At first sight, the idea that two such hothouse orchids as Medlar Lucan and I might concern ourselves with Sport seems incongruous in the extreme. The only sort of running either of us has done is that of a bath full of unguents and rose petals; the only time we have vaulted a bar was to get at an exceedingly rare bottle of absinthe we had spotted at Ludovico’s in Venice; and the only time we employ ‘Higher – Faster – Stronger’ is as a mantra in our search for the perfect narcotic.

This is not to say that we are entirely indifferent to sport and sporting events. I have a clear memory of the seminal moment in 2005 when it was announced that London had been chosen as the site for the 2012 Olympic games. Medlar and I had been living in Cuba for several years and we were listening to the news as it came crackling through in Spanish on the radio of our 1961 Pontiac Bonneville while cruising the muddy streets of Baracoa. Both of us were jubilant. Not because we have any particular affection for London. Quite the contrary. The city is nothing more than a collection of undistinguished villages which draws in more and more vulgar spivs every year. No, the reason for our jubilation was the prospect of witnessing a massive expenditure by the capital on an extravagantly pointless event which would have had any heavily bemedalled despot clapping their hands in delight. If ever you are looking for evidence of a nation in decline, the single-minded desire to host a major international sporting event is it. Small wonder that the word ‘ludicrous’ is derived from the Latin for a game.

At the time of the announcement, of course, conditions were such that the whole project had at least a slim chance of success. The moment was opportune. A buoyant economy. No sign of recession. Imagine, then, our increasing delight as the global economic crisis turned what seemed to be a bold venture into one of supreme foolishness. (It was also at this time, by coincidence, that Medlar was spending more and more time in Greece, the birth canal of the Olympics, watching with fascination as that country sank into a mire of debt). The stage was set for us to sit back and enjoy a performance of hubris and futility by a decayed imperial power which, like Norma Desmond, refuses to believe it is a has-been and embrace its own decline. “Oh, to be a Decadent in such an age when downfalls are everywhere and every inch of common air throbs a tremendous prophecy of greater catastrophes yet to be.” This is not exactly what Walt Whitman wrote, but I like to think it is what he meant.

But the question remains: Why this book? What possible link is there between Decadence and Sport?

Before Medlar and I arrived in Havana in early 2000, we would have answered this question with an unequivocal: “There is none”. However, our first lodgings in the Cuban capital happened to be a suite of splendidly decrepit rooms on the piano nobile of a crumbling 19th century town house which also housed a fine old Havana boxing club. Up through the floorboards each day drifted the perfume of youthful sweat and leather, the sweet dull sound of padded fist against flesh accompanied by staccato grunts. Each time we passed the massage room on our way out of the building we caught a glimpse of the hardened bodies of young athletes glistening like dark armour stretched out on the tables. Some were injured and receiving treatment. Undoubtedly, there is no more beautiful sight than that of a polychromatic bruise or a bead of blood against dark skin. I was immediately transported back to the time we spent in New Orleans, and in particular to the Fencing School there. It was not long before Medlar and I, irresistibly drawn into the atmosphere of the boxing club, found ourselves acting in an unofficial capacity with regard to its young denizens. We became self-appointed… what? ‘Spiritual advisors?’ That might be too strong a term, although ‘sports psychologists’ or ‘motivators’ would be simply hideous. The correct title does not occur to me at the moment, although we now perform a similar role for a Women’s Gymnastics team. More of that anon. Let us return to the subject of bruising.

Pain, the Athlete and the Decadent

One area where the Athlete and the Decadent meet and embrace is on the field of pain. The Athlete confronts pain, courts it, risks it, whether from pushing the body beyond its natural limits, or through violent contact with other bodies. The Decadent likewise embraces pain, seeks it out, whether it is self-inflicted, inflicted by others or on others. Both Athlete and Decadent seek to break through the barrier of pain; the one to gain self-overcoming, the other to find transcendental pleasure. Are not all Athletes masochists at heart?

Ever since my boyhood I have known that writing about and describing the nature of pain is exceptionally difficult, as slippery as the depiction of any ecstatic moment. Some would say that pain destroys language, stops up the voice, makes writing impossible. (Nietzsche could only write by anaesthetising himself with ferocious medicines). Or else it causes the body to revert to the noises and cries which only emerge when language gives out. This is why certain crazed physicians have developed dolorimeters and sonic palpometers to measure pain scientifically. It is noteworthy that the medical profession knows next to nothing about the one thing it deals with daily. This is a bit like the Catholic church admitting that it does not really understand what Sin is. (I can assure you, dear reader, that the Catholic church understands everything there is to understand about Sin). So, in a spirit of investigation, I set myself the task of carrying out some research into the matter of describing pain, which I am sure will make a major contribution to our body of knowledge.

Early on in my searches I came across a very exciting-sounding article on this subject. It was entitled Camp Sports Injuries: Analysis of Causes, Modes and Frequencies. I wondered what might count as a ‘camp sport’, let alone a ‘camp sports injury’. Drag queen cage slapping, perhaps? Or feather duster fencing? I imagined the dislocated wrist, the handbag cut, the agony of the broken fingernail or smudged lipstick. In reading the article I found out that it was concerned with injuries sustained by 7 to 15 year-olds in an American summer camp. Here was precisely the sort of academic research for which Medlar and I are particularly well qualified. I lost interest however when I realised that the point of the article was to suggest ways in which such injuries might be prevented.

Next I turned my attention to pain indexes, or indices (depending on whether one protects oneself with Durexes or Durices). Despite the difficulty of giving an accurate account of pain, some have attempted to go even further and to categorise it, to ascribe a value to different levels of pain. One such is the Schmidt index. Designed by entomologist Justin O. Schmidt, it purports to describe and rank the pain experienced from insect bites and stings. Hence:

1.0 Sweat Bee. Light, ephemeral, almost fruity. A tiny spark has singed a single hair on your arm.

1.2 Fire Ant. Sharp: sudden, mildly alarming. Like walking across a shag carpet and reaching for the light switch.

1.8 Bullhorn Acacia Ant. A rare, piercing, elevated sort of pain. Someone has fired a staple into your cheek.

2.0 Bald-faced Hornet. Rich, hearty, slightly crunchy. Similar to getting your hand mashed in a revolving door.

2.0 Yellowjacket. Hot and smoky, almost irreverent. Imagine W. C. Fields extinguishing a cigar on your tongue.

2.2 Honey Bee and European Hornet. Like a match head that flips off and burns on your skin.

3.0 Red Harvester Ant. Bold and unrelenting. Somebody is using a drill to excavate your ingrown toenail.

3.0 Paper Wasp. Caustic and burning. Distinctly bitter aftertaste. Like spilling a beaker of hydrochloric acid on a paper cut.

4.0 Tarantula Hawk. Blinding, fierce, shockingly electric. A running hair drier has been dropped into your bubble bath.

4.0+ Bullet Ant. Pure intense brilliant pain. Like fire-walking over flaming charcoal with a 3-inch rusty nail in your heel.

This index is of course absurd, a mixture of hyperbole and the surreal, accompanied by a numerical value which relates to nothing at all. It fails to convey even a vague sense of the nature of pain. This is because it is obviously not rooted in personal experience. How can Herr Schmidt possibly know what it feels like to fire-walk with a three inch rusty nail in his heel? Besides, the whole point about fire-walking is that the walker feels no pain. No, this won’t do.

A more engaging read is the McGill index which goes to the opposite extreme, attempting to furnish a broad, common vocabulary for levels of pain. Sufferers are presented with a list of adjectives to choose from:

Flickering, Pulsing, Quivering, Throbbing, Beating, Pounding

Jumping, Flashing, Shooting

Pricking, Boring, Drilling, Stabbing

Sharp, Cutting, Lacerating

Pinching, Pressing, Gnawing, Cramping, Crushing

Tugging, Pulling, Wrenching

Hot, Burning, Scalding, Searing

Tingling, Itchy, Smarting, Stinging

Dull, Sore, Hurting, Aching, Heavy

Tender, Taut (tight), Rasping, Splitting

Tiring, Exhausting

Sickening, Suffocating

Fearful, Frightful, Terrifying

Punishing, Gruelling, Cruel, Vicious, Killing

Wretched, Blinding

Annoying, Troublesome, Miserable, Intense, Unbearable

Spreading, Radiating, Penetrating, Piercing

Tight, Numb, Squeezing, Drawing, Tearing

Cool, Cold, Freezing

Nagging, Nauseating, Agonising, Dreadful, Torturing

Reading this index reminds me of a weekend house party which Medlar and I attended recently in Montevideo. It is more of menu than a description. One could imagine arriving at one of Berlin’s more recondite establishments and ordering ‘some no. 4 followed by no. 10 and a side order of no. 20.’ But again, this index is too inconsistent. How can pain be simultaneously ‘annoying’ and ‘unbearable’? The problem with these indexes is that they are all terribly negative. They fail to register, or even acknowledge, the extent of pleasure which can be derived from pain.

In response to the inadequacy of existing indexes, my own efforts in this area have resulted in the Lucan and Gray Colour-Coded Index of Decadent Pain, based largely on E. M. Cioran’s idea that the limit of every pain is an even greater pain. The index reads thus:

Blue – this is the level of pain which evokes the involuntary gasp, the uncontrolled whimper, a point at which the body speaks directly without the will of the speaker. Medlar is very keen on the distinction between pain which causes an inhalation, as if the body wants to take in the intensity to control it, and pain which causes an exhalation, as if the body wants to expel the sensation. For the Decadent of course the former is by far the preferable course of action. Anyone who has felt the spiteful bite of the cane will recognise this.

Green – tears and sweetness. Often this level of pain is accompanied by other physical sensations such as the scent of rotting lilies or a feeling of sanctity. This pain can be administered by somebody close to you, or else a stranger. It results in feelings of deep-seated gratitude towards the perpetrator. The narrator of Venus in Furs writes: “The blows fell rapidly and powerfully on my back and arms. Each one cut into my flesh and burned there, but the pains enraptured me. They came from her whom I adored, and for whom I was ready at any hour to lay down my life”.

Black – dark pain. Depression and fear and anxiety. It becomes a companion and tormentor, one which never leaves your side. You may attempt to befriend it. You may even take it as a lover, in the hope that this will transform it in some way. The horror of this pain is that it has no source and no cause.

Red – the scream. This is that pain which one feels of such intensity that it leaves one teetering on the edge of the abyss, quite uncertain as to whether or not one will plunge headlong into unconsciousness. It is that liminal state across which the spirit wanders back and forth, like a brain-damaged boxer.

Purple – the moment of sublime beauty. The moment when pain becomes so intense that it surpasses all understanding and perception. It is no longer something that happens to the body; it is the body. This is the point where pain is both closest and furthest away. In other words it is where pain threatens to become transcendent, or even sublime. To misquote Antoine Artaud:

The purple horror

Of exceeding oneself

In that extreme pain

Which will no longer be pain in the end.

That is what I never stopped thinking.

White – this is the rarest and most exquisite of the stages. The moment should be looked out for and yet any anticipation of white pain will change its nature. The body has to be taken unawares. Often it lasts little more than a second or two and it precedes a loss of consciousness. At first there appears to be no pain at all. There is a moment of great calm, like the eye of a storm, before an explosion of hurt where the body, the mind, and the soul disappear. The degree of pain experienced is such that it fills the entire universe.

The more perceptive reader will have noticed that as an ensemble these colours constitute the spectrum of a bruise on the skin of a red-haired woman. In my experience red-heads are not only peculiarly susceptible to livid bruising, which the more intriguing among them rejoice in, but also their particular bluish-white complexion acts as a perfect setting for the myriad colours of subcutaneous bleeding.

But let us consider further this connection between Sport and Masochism. With regard to the latter, some of the most spectacular and ruthless masochists in history have been Christian saints and mystics. In certain respects they are quintessentially Decadent characters. St Margaret Mary Alacoque remarked that ‘None of my sufferings has been equal to that of not suffering enough’. One of Eckhart’s pupils, Blessed Henry Suso, designed and wore a special undergarment lined with 150 sharpened nails that constantly pierced his skin; a sort of super-cilice. He also wore gloves lined with sharp tacks intended to prevent him from picking off the lice and other insects that fed on his body. And when it comes to a description of Saintliness, we can do no better than to return to E. M. Cioran. According to this latter-day Nietzsche, Saintliness cannot exist without the voluptuousness of pain and a perverse refinement of suffering. Furthermore, he sees sanctity as a special kind of madness; ‘…while the madness of mortals exhausts itself in useless and fantastic actions, holy madness is a conscious effort towards winning everything’.

Our contention is that the Athlete, whose sport is often referred to as a ‘vocation’, is consumed by this form of holy madness. According to Cioran, next to the mystic, the Saint is the most active of men. The Saint is also the source of all tears. He writes: ‘As I searched for the origin of tears, I thought of the Saints… To be sure, tears are their trace’. And how closely associated are tears with sport! How often do we see our Athletes dissolve into tears before our very eyes after their moment of extreme exertion! (Medlar once had a mistress who responded in the same way). What was formerly considered a reprehensible and self-aggrandising display is now compulsory in the sporting world. Tears must accompany triumph and failure alike. Superficially they are said to bear witness to an outpouring of emotion experienced after testing the body to the limit. However, my sense is that the tears of the Athlete are related to a reconnection with the decadence of Medieval religiosity and a deep-seated sense of the Loss of Paradise. I find this thesis compelling and cogent, although there are some senior theologians who think it over-stretched.

Mention of Medlar’s erstwhile mistress leads me seamlessly to another gilded couch upon which the Decadent lies down with the Sportsman: breathlessness. Any of us who have engaged in auto-erotic asphyxiation will recognise the sensual attraction of that state where the Athlete, at the end of a contest, is gasping for breath, desperate to revive an oxygen-starved system. This is very close to the ideal conditions for an orgasm of great intensity. The condition of extreme breathlessness links the Athlete to de Sade, who in Justine describes a scene where Thérèse’s master, Roland, foresees pellucidly his destiny – dancing at the end of the hangman’s rope. In order to face this fate with equanimity, he needs to know whether the accounts of erotic stimulation which accompany hanging are true or not. And he tells Thérèse that she has to help him in this. She relates the outcome thus:

We take our stations; Roland is stimulated by a few of the usual caresses; he climbs upon the stool, I put the halter round his neck; he tells me he wants me to curse him during the process, I am to reproach him with all his life’s horrors, I do so; his dart soon rises to menace Heaven, he himself gives me the sign to remove the stool, I obey; would you believe it, Madame? nothing more true than what Roland had conjectured: nothing but symptoms of pleasure ornament his countenance and at practically the same instant rapid jets of semen spring nigh to the vault. When ’tis all shot out without any assistance whatsoever from me, I rush to cut him down, he falls, unconscious, but thanks to my ministrations he quickly recovers his senses.

“Oh Thérèse!” he exclaims upon opening his eyes, “oh, those sensations are not to be described; they transcend all one can possibly say: let them now do what they wish with me, I stand unflinching before Themis’ sword!”

In our relentless pursuit of scientific knowledge, Medlar and I have approached the Universidad de la Revolución with a proposal to carry out controlled experiments on some undergraduate volunteers comparing the breathlessness of Athletes at the end of a sprint with that of male or female subjects at the moment of orgasm. Our findings will be published in a suitable journal as soon as we have them.