3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

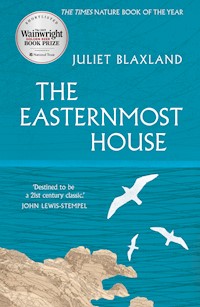

THE TIMES NATURE BOOK OF THE YEAR 2019!Shortlisted for the Wainwright Golden Beer Book Prize!Shortlisted for the East Anglian Book Award 2019!If you enjoyed Raynor Winn's The Salt Path, Amy Liptrot's The Outrun, Chris Packham's Fingers in the Sparkle Jar or Helen MacDonald's H is for Hawk, you'll love The Easternmost House.Within the next few months, Juliet Blaxland's home will be demolished, and the land where it now stands will crumble into the North Sea. In her numbered days living in the Easternmost House, Juliet fights to maintain the rural ways she grew up with, re-connecting with the beauty, usefulness and erratic terror of the natural world.The Easternmost House is a stunning memoir, describing a year on the Easternmost edge of England, and exploring how we can preserve delicate ecosystems and livelihoods in the face of rapid coastal erosion and environmental change.With photographs and drawings featured throughout, this beautiful little book is a perfect gift for anyone with an interest in sustainability, nature writing or the Suffolk Coast.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Juliet Blaxland is an architect, author, cartoonist and illustrator. She is the author and illustrator of twelve children’s books, and a prize-winning photographer. She grew up in a remote part of Suffolk and now lives on a crumbling cliff at the easternmost edge of England.

First published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Dochcarty Road

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9UG

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored or transmitted in any form without the express

written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Juliet Blaxland 2018

Editor: Moira Forsyth

The moral right of Juliet Blaxland to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland

towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-912240-54-8

ISBNe: 978-1-912240-55-5

The Easternmost House is dedicated to all the people who have been physically involved in the making of the British landscape in the past, and to those who still live and work in the countryside or on the land today: farmers, fishermen, shepherds, hedge layers, thatchers, stone wallers, flint knappers, barn builders, farriers, racehorse trainers, grooms, vets, pub landlords, village shopkeepers, butchers, tractor drivers, ‘fellows who cut the hay’, fruit pickers, gardeners, tree planters, landowners, river keepers, ghillies and everyone else not yet mentioned . . .

I am also very grateful to Jane Graham-Maw of Graham-Maw Christie, literary agent, Moira Forsyth of Sandstone Press, publisher, John Lewis-Stempel, author and Country Life columnist, and Giles Stibbe, husband, for their belief in this book before it really existed.

Twitter @JulietBlaxland

#TheEasternmostHouse

‘The great thing about Suffolk is that once you arrive here, you are in a kind of simple environment, a comfortable, gorgeous place, where the people will be delightful and friendly. They don’t go off to wild lives or other distractions with noise and traffic. There is also the way it looks. It’s such a beautiful county. If you live here, you get really used to the unbelievable beaches, the curve of the land, the beauty of the villages.

If you are making a film about England, you can find everything you want, and more, here.’

Richard Curtis, on filming in Suffolk

June 2018

CONTENTS

Influences

Introduction

1 January: The Beach and the Cliff

2 February: Music in Its Roar

3 March: The Timber Tide

4 April: Lanterns on the Beach

5 May: Fur, Feather, Fin, Fire and Food

6 June: A Night on the Dune

7 July: Summer Lightning

8 August: To the Harbour at Sundown

9 September: Harvest Dust

10 October: An East Wind and a Thousand-mile View

11 November: Still Dews of Quietness

12 December: Ring of Bright Water

Tailpiece

The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling up from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot.

Henry Beston

INFLUENCES

I live in a house on a windblown clifftop at the easternmost edge of what used to be the easternmost parish of England. The church fell into the sea in 1666, and this house – itself called The Easternmost House – has possibly only three summers left before it too is lost to coastal erosion. I wanted to describe a year of life on this crumbling cliff at the easternmost edge of England, in all seasons and in all weathers. This ‘year of life’ is in fact the distillation of several years of life. There are stories, and beginnings, middles and ends, but not necessarily in that order.

We live here all year round, and have done so for several years, but I cannot say how many, for fear that to do so might itself tempt fate to render our life here episodic or experimental, and to end it with the destruction of the cliff and our house in a sudden storm.

Two nature-writing classics in particular are the ancestors of this book. The first is The Outermost House, by Henry Beston, first published in 1928, which takes as its subject a year of life on the great beach at Cape Cod. The second is Ring of Bright Water, by Gavin Maxwell, first published in 1959, which is about much more than the otters for which it will always be remembered. In each of these two books, the actual lives lived were the main adventure, and the writing was the offspring of the life. In each, there is also a deliberate attempt to live away from the mass of humanity, and to relate more closely to the natural world. Both also share an unspoken renunciation of the values of an urbanised society, and of materialism for its own sake. I suspect that Henry Beston’s lament that the world is ‘sick for lack of elemental things’ must be even truer today than it was in 1928. Gavin Maxwell’s assertion that places such as Camusfearna in Scotland are symbols of freedom from ‘the prison of over-dense communities’ and the ‘incarceration of office walls and hours’ echoes Beston’s discomfort, but thirty years later. To their perceived horrors of the modern world as it was then, we can add a panoply of new ones: overpopulation, social media, plastic, pylons, sprawl.

Xanadu, Shangri-La, Tir na n’Og, Avalon, Camusfearna, Arcadia. These names are all evocations of an archetype of an idyll, an earthly paradise set in a landscape of natural beauty, sometimes a place of myth or mystery. A suitable dwelling for such a scene might be a temple folly set in acres of rolling parkland, a timber cabin in a forest, a whitewashed cottage in a rugged landscape of rock and sea. But these places exist primarily in the imagination, so they can be changed, adjusted and revisited at will.

The Easternmost House is our real-life version, and throughout this book I will try to make this place as real to you as it is to us, and to convey some of the natural wonders surrounding us in this magical landscape of light and sky and water.

Look to this day!

For it is life, the very life of life.

Look well, therefore, to this day!

INTRODUCTION

I had a rural 1970s childhood. Much of it was spent in what would now be seen as significant physical danger, often in literal and social isolation, sometimes with only animals for company, but all of which was normal for the time and place. My sister was older, earnest and bookish, and the noisier tribe of cousins and friends lived several miles or counties away, so I invented some imaginary brothers for everyday company, and to liven things up. I was also a tomboy, and for a time I privately self-identified as a dun pony.

It was a world in which death and disaster were ever-present. Drownings, broken bones, chainsaw incidents, fires, injuries by farm machinery and rogue elements of buildings, tramplings by beware-of-the-bulls and/or motherly cows protecting calves, were regular, if not quite commonplace.

There were also countless separate dramas involving ponies, including one in which I was caught in a thunderstorm in a wide-open landscape, and had to decide how not to be struck by lightning. With hindsight, I should have led the pony into an isolated church on our route, which would have had a lightning conductor on its tower and offered a little flint fortress of physical protection. But as I was only eleven and operating in a slightly more God-fearing era than now, the leading-the-pony-into-the-church option passed me by. In the event, I took a direct line across the country in the manner of a nineteenth-century hunting print, and just galloped home.

I invented methods for combatting my everyday dangers and demons. The dangers were self-evident, and my demons were the more emotional, invisible side of things, such as having to go reluctantly back to boarding school seven counties away, from the age of ten, or not crying when guinea pigs and dogs and ponies, and eventually people, died of old age.

Having settled into an inescapably odd boarding-school routine of Latin tests and fencing practice during term time (as in sword-fighting, not creosote), punctuated by the rural rhythms of being barked at by tweedy retired colonels in various horse-related contexts in the holidays, by the time I reached my eleventh birthday I would have been perfectly equipped for a life in the Household Cavalry.

I know in reality that for much of the time as a child I was either cold, wet, frightened or mildly unhappy, yet the distilled memory is of one perpetual summer holiday, magically set in the long, hot summer of 1976. This trick of human memory is one of nature’s small miracles, a talismanic nugget to hold on to for life.

I got away quite lightly, in terms of horse-related-injury, but in one teenage incident I suffered a head injury which I believe may have changed my brain and the way I think. I became more extreme and lateral-thinking and drawn to a new world, of Rothko and Miro and Brutalism and Deconstructivism, and curious about anything else that seemed unfamiliar, edgy, incomprehensible or just interesting. Perhaps this set me on a path to the architect and architectural cartoonist that I eventually became. These small but potentially life-changing dramas were considered completely unremarkable in the rural context of that time.

Later, when I lived in London, I realised that my habitual and evidently necessary rural alertness had translated itself to coping with the hazards of city life. Instead of looking out for falling branches, I would cross the road to avoid scaffolding in a high wind. Instead of being wary of being kicked by a horse by assessing its body language, I would scan the mean streets of London for potential murderers and muggers by reading the same uneasy signs. I never did acclimatise to traffic, which appears to me as a river full of crocodiles would to a zebra foal. One day, the scaffolding near our office actually did fall down.

So when I eventually returned to my rural roots and the familiar Suffolk landscape as an adult, living and working – as many country people do – often outside, often alone, often up a ladder, chopping wood with an axe, climbing around an old building, dealing with large and excitable animals, planting trees, tending bonfires, or otherwise being in some degree of danger which rarely arises in an office, I found that what I had always thought of as my tomboy habits actually turned out to be useful training for our life on the cliff.

The haar is an eerie sea-fog which cloaks our cliff and renders the edge invisible. On one such foggy day, when my soldier husband Giles was in a war zone in Afghanistan, I turned for home down our track and saw at the end, near the edge, the ghostly figures of two men. Instantly I assumed they must be Army Welfare Officers. As I passed the farm buildings, I had already imagined that Giles had ‘life-changing injuries’. By the time I reached the opening in the hedge by the metal gate, I had the idea that he had ‘not survived his injuries’. As I reached the end of the track and the cliff-edge, so that the men became bigger and nearer, I could see that they both held clipboards.

We had been briefed about the protocol of such things in a little book, including what happens when something happens to ‘your soldier’. IED. Improvised Explosive Device. Invisible. Lethal. Life-changing. Fatal. So sorry. Not survived. In that short distance these phrases became seared onto my brain as blackly as if they had been burnt on with a branding iron. Now these two harmless grey figures had come to tell me I would now be alone, properly alone, forever.

I had heard from somewhere that people who are on the receiving end of sudden bad news, of a death in a car crash, of a suicide, or of instant widowhood at the hands of an IED, often make it even more difficult for the bearers of the bad news, by not taking in the message. People are in denial. They do not fully comprehend that what has happened, has happened. So, as I trundled up the track towards these misty grim reapers, I rehearsed how I would sit them down and offer them a cup of coffee. I would tell them that I had heard about this bad-news-denial syndrome. I would reassure them that I understood, that death was to be half-expected when you are in the army. That modern soldiers of all ranks have chosen their job, or at least their vocation. That the stiff upper lip has served us well and thank you, yes, I will be fine absolutely. But even these carefully-marshalled thoughts were already beginning to become muddled.

The grey men were by now very close, so I stiffened the sinews and summoned up the blood to speak to them. Or at least try to listen to them. They mumbled a reply, the fragmented gist of which included a grey fog of dull corporate words: ‘Council . . . engagement . . . team . . . assessing . . . the progress . . . of coastal erosion . . .’

Assessing the progress of coastal erosion . . . I could have pushed them off the cliff.

I could have explained about the IED and the emotional haar that had just engulfed me. But distant echoes of wartime grandparents, Nimrod at the Cenotaph, tweedy colonels and all our unfashionable old-school training somehow conspire to suppress any outward show of emotion at times of crisis, so I just smiled sweetly and offered them a cup of coffee as planned. The council engagement team looked mildly surprised at this unexpectedly random hospitality, but chattily enjoyed two mugs of instant coffee each, looking out to sea, and then shuffled off into their logo-ed van with a few cheerfully engaging small-talk remarks about what an odd place to live, etcetera. And what odd people, no doubt, not far away in their thoughts.

Giles was, for the moment, safe. But this house was very much not.

People have often asked what it is like to be an army wife alone on a cliff with a husband away in a war zone and how you avoid being overwhelmed with loneliness and anxiety. I have never been lonely when alone. What makes me lonely is people asking if I am lonely and what makes me anxious is people asking if I am anxious. My antidote to loneliness and anxiety is to have physically and/or mentally engaging projects. In my London days, I used to engage in guerilla gardening and gritty urban photography tours on my bike and spent long afternoons helping with a group of volunteers taking disabled people for rides on very quiet horses and ponies of appropriate size and sweetness. Now, I might build a chicken run, plant a kitchen garden, clip a hedge or rescue a greyhound. Anyone who lives in the country knows that there is also a constant need to engage in what might be called ‘unprofessional mass catering’, for causes or committees, guests or glut-processing reasons.

Reading about the source of the anxiety helps, in this case Afghanistan. The thing about war zones is you never know when they are safe. Soldiers in any war are sometimes safe. They know when they are safe, but we at home do not. Constant anxiety, both here and there, becomes normal and familiar for the whole six months, until the plane lands. The other thing about war zones is that everyone else is going about their civilian daily business not thinking about war zones, so you keep your war-zone thoughts in a separate bubble, much as I imagine you might keep your deeply-religious thoughts or your bank-robbing thoughts in a separate bubble, at least when in the company of people who might not share or understand them.

Conversely, we are sometimes in danger, while those in the war zone think of home as perpetually cosy and safe. I know that when I walk alone on our beach, if something happened to me, I would probably not be rescued, at least not in time. Therefore, thinking back to that list of rural disasters, I deliberately remind myself that it is up to me, and me alone, to be watchful and have imagination about what sort of ‘something’ might happen, and where I place myself, and whether this is a safe place to put my feet, and whether this wet sinking sand is going to swallow me up, and so on. It becomes second nature.

Once, a large branch of a tree narrowly missed crashing down on a person as she rode her bicycle up the drive when I was a child. More recently, a visitor was killed, buried by a cliff fall a few miles to the south of us. When a report appeared in the paper, of people desperately trying to rescue this person and a dog with their bare hands, a detail that was not mentioned but which was visible in the picture, was that the tide was high so the beach was narrow. Now, when I walk on the beach alone, I do a rough mental calculation that there is enough beach to equal the height of the cliff, and I walk beyond the imagined height-line on the beach. If the tide means the beach is narrower than the height of the cliff, I go a different way. In company, I might take more risks with the elements, because I might be rescued, but even so, I think about each situation as an individual, not one of a herd.

As I finished writing this book and naturally returned to the beginning, a full-moon storm had just exposed the sea defences on the beach below us. When we first arrived, these concrete pyramids were at the foot of the cliff, but now they are many metres away on the beach, or more usually under the beach, measuring our ebbing time with invisibly brutal accuracy. By eye, it is clear that the distance from the sea defences to the bottom of the cliff is now twice the distance from the cliff edge to the house itself. The two-thirds on the beach equal the ten years we have been here, so the one-third on the clifftop implies that we might still have five years. Two-thirds of our time here seem to have just vanished into thin air yet I find the literal, visible erosion of time to be oddly comforting.

The last defined purpose of this place was in the war, looking outwards not inwards, scanning the world beyond. A new planning application proposes to knock down the farm building which then served as the radar station. By chance, a photograph I took of that building ended up as the winner of the inaugural ‘Suffolk Beauty’ photography competition, so it is recorded for posterity. Little did I know how prematurely that significant little landmark would be destroyed, and by forces other than the erosion.

The Easternmost House is a portrait of a place that soon will no longer exist. It is a memorial to this house and the lost village it represents, and to our ephemeral life here, so that something of it will remain once it has all gone.

At the beach, life is different. Time doesn’t move hour to hour, but mood to moment.

We live by the currents, plan by the tides, and follow the sun.

Anon/Unknown

The Beach and the Cliff

I have desired to go

Where the springs not fail,

To fields where flies no sharp and sided hail

And few lilies blow.

Where no storms come,

Where the green swell is in the havens dumb,

And out of the swing of the sea.

Heaven-Haven

1

JANUARY

Genius Loci, A Sense Of Place

East of London, east of Ipswich and east of all the rest of England, there sits upon a cliff this little house, this remote house from whose kitchen table I try to convey the spirit and beauty of the place to others. It is a windblown house on the edge of an eroding clifftop at the easternmost end of a track which leads only into the sea. The farm track looks as if it wants to continue for a mile or two, but it has been hacked off roughly by the wind and sea and erosion. There used to be a village here and there used to be several hundred more acres of farmland. This farm used to own the easternmost land mass in the whole of Britain, and the little village used to be at the heart of the easternmost parish: Easton Bavents.

The word ‘east’ appears three times in our Easton Bavents address, four if you add Easton Farm and five if you count the fact that we are in East Anglia. There is much here that ‘used to be’, and it seems sad and unromantic that the actual easternmost point of Britain is now an uncelebrated spot in Lowestoft. Soon, the house we live in will be described as the house that ‘used to be’ right on the edge. The jagged edge is always a warning, of recent erosion, of unknown cliff conditions underfoot, of new chunks of land having fallen into the sea overnight.

The church of St. Nicholas Easton Bavents used to be the easternmost church in England, and it was the presence of the church that made Easton Bavents the easternmost parish. The easternmost land mass stuck out into the sea like a nose, marked on old maps as Easton Ness. The last known vicar here was appointed in 1666, and a storm soon after that destroyed the church. The church of St. Nicholas is now a mile and a half out to sea, further east than the more famous vanished churches of the ‘lost city’ of Dunwich, and without the mythical bells supposedly ringing on stormy nights. The role of churchwarden here is mercifully light on duties, reduced only to a ghostly sense of responsibility to keep the memory of the easternmost church alive.

Within sight from the house and the cliff is a distant postcard view of Southwold, but the cliff is a wild place, bashed about by raw nature. In summer it is like living in a Mediterranean paradise. In winter it can be like living on a wind-lashed trawler. The Suffolk coast is eerie and deceptive like that. This watery landscape looks pretty but it conceals many ways to cast tragedy over the unwary or the over-confident on their summer holidays. The photogenic harbour with its picture-book boats hides its racing tides. The sun-blessed reedbeds hide their disorientating scale and dangerously invisible water-filled dykes. The clifftop path through casual drifts of wild flowers hides lethal cantilevered ledges of sand, unsupported land, hovering over thin air, preparing imminently to crash onto the beach below. Land, sea and sky are unheeding of the line in the hymn, ‘its own appointed limits keep’. Here, the ‘mighty ocean deep’ keeps to no appointed limits.

You can see the house from a long way off if you know where to look. From particular viewpoints, its tiny form is glimpsed on the ridge beyond the reedbeds, sheltering under the wide skies in the distance just to the left of the pepperpot white lighthouse. A line of Scots Pines on another ridge forms the sort of treescape familiar to Pooh and Piglet and Eeyore. Driving along the road about a mile away, you sense but cannot see that the land is about to run out, and the little house stands firm against painterly swoops of light and colour and cloud, in a place where it is never quite clear which is land and which is sea or sky. The house is invisible to all but those who know intimately how it is placed in the lie of the land. Alone, away from the herd, it is only from afar that you really appreciate how tiny this house seems against the vastness of nature’s uncaring dramas and our wide East Anglian skies. From the sea, it appears as a house from an old-fashioned story book.

Imagine you are approaching the house. You could walk past the pier and the beach huts in Southwold and continue north to where there is a sign saying PRIVATE EASTON BAVENTS (perhaps a subordinate of General Principle) and just keep going. By car, you would turn off a winding rural road, into a long farm track with a sign warning of SLOW CHILDREN AND ANIMALS and follow the telegraph poles all the way to the end. However you achieve it, you need to be alert once you arrive, because this is the edge of the cliff, and before you now, only a small sign decorated with a skull and crossbones and the message DANGER CLIFF ERODING, then a vertical drop and the sea.

The views from the danger-cliff are friendly. To the north there is an uncluttered view of open arable land and the beach towards Benacre, pronounced BENakker, not Ben Acre like a character from The Archers. To the south, there are more crops and beyond that, Southwold: pier, lighthouse, brewery, church, water tower. The cliff hides lines and layers of history beneath your feet, but from the beach, the layers are made visible by the erosion, telling part of the story of millions of years of time and our place in it: about 60 million years since the birds evolved, 10 million years since the first humans, two million years’-worth of tiny animals now exposed to our eyes in the cliff, and about 6000 years since this piece of land was walkable from mainland Europe, via Doggerland.

It is odd to think how our ancient ancestors would have experienced exactly the same great rhythms of sea and tide and wind, and the same silence. The sound of the sea crashing on the beach must be deeply embedded into our collective race memory. Will future geologists look askance at the damage wrought by only fifty years of plastic? Will those plastic islands in the Pacific that we read about in despair become layered with airborne earth and guano and seeds and renewal and eventually become real islands lush with their own natural beauty?