13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

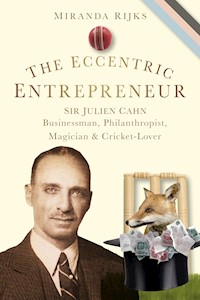

Sir Julien Cahn was possibly the most successful eccentric in 1930's Britain. A complex man with diverse interests, Cahn's visions influenced cricket, business, politics and medicine. Having built the largest mass-market furniture empire in England, incorporating the well-known Jays and Campbells, he used wealth to fund his extraordinary hobbies: as a cricket fanatic he established the internationally renowned Sir Julien Cahn's XI, outplaying national teams during lavish world tours; as an accomplished magician he built a magnificant art deco theatre and cinema at his home, Stanford Hall, and staged illusions so spectacular that he was invited to perform at London's Palladium Theatre. Despite being a Jew in the 1930s, Cahn managed a rapid ascent up the social ladder, and even found himself embroiled in the buying of honours scandal. Yet his largesse was legendary, supporting medicine and agriculture, and as Chairman of The National Birthday Trust Fund he was instrumental in developing the first human milk bank and introducing anaesthetics in childbirth. In this fascinating life story of Cahn, Miranda Rijks goes beyond penning a simple biography, and paints a vivid picture of life in upper-class Britain: a world of wealth and splendour that is barely conceivable today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

SIR JULIEN CAHN

Businessman, Philanthropist,

Magician & Cricket-Lover

MIRANDA RIJKS

‘The opportunity of a lifetime should be seized in the lifetime of the opportunity.’

Sir Julien Cahn Bt.

First published 2008 This edition published 2011

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved © Miranda Rijks, 2008, 2011

The right of Miranda Rijks, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7218 8MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7217 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

1 A Precocious Child

2 The Power of Philanthropy

3 Luck, Largesse & Laughter

4 Seizing Opportunities

5 Bodyline & Baronetcy

6 One Big Family

7 Upstairs & Downstairs

8 Grand Illusions

9 The Last Tour

10 An Untimely End

11 After Effects 204

Thanks

Bibliography

1

A Precocious Child

On the afternoon of 20 October 1890, a day before his eighth birthday, Julien Cahn was walking along Waverley Street, Nottingham, with his governess. A horse and carriage swept past, the rush of air rustling the austere governess’ skirts, the whiff of horse dung pungent to her nostrils. She stopped abruptly and turned to her diminutive charge.

‘Julien – you are a young man now. You should stand on the outside of the pavement and I should stand on the inside.’

Julien queried why.

‘The man should always protect the lady from passing carriages,’ she explained.

Julien thought for a moment. ‘No, that can not be right!’ He paused. ‘We can always get another governess but there is only one Julien!’

A small boy with dark hair and hazel eyes, Julien was the son of Albert and Matilda Cahn. His heritage was typical of the émigré Jew. Albert Cahn was born in 1856 in Russheim Germersheim, Rheinpflaz, a small village near Mannheim in the Rhineland area of Germany, reasonably close to the border of France. For several generations, Albert’s family had played a prominent role in the tiny Jewish community. During the 1860s and 1870s, Germersheim became an uncomfortable place for a young ambitious Jew. Prompted by the indigenous anti-Semitism in Germany, young Albert decided to emigrate to England, leaving his family behind. Over the years, Albert never forgot his origins or his faith, and when he eventually died, he left money to maintain his parents and grandparents’ graves. There are no records indicating when Albert moved to England, but by 1881 he was employed as a provision merchant and lodging at 26 Edward Street, Cardiff.

On 4 January 1882, Albert married Matilda Lewis, the eldest daughter of Dr Sigismund Lewis of 155 Duke Street, Liverpool, in an orthodox Jewish ceremony under a simple chuppah at her parents’ house. He married well. Sigismund Lewis had studied medicine in Berlin and practised in Hamburg before settling in Liverpool during the 1850s. He was an eminent, erudite and kindly doctor, single-handedly providing health services to the Liverpool Jewish community and later appointed honorary medical officer to most of the community’s welfare institutions and schools. He was also medical officer to Cunard and various other steamship companies for forty years. His good works towards the poor and the Jewish community were well recognised both in Liverpool and in Berlin. Sigismund married Eliza Goldstucker and they had seven children: two boys and five girls, one girl dying in infancy.

The Lewis family lived well. When the children were still young they moved to Duke Street, an area that had been home to the first merchants of Liverpool. By the mid to late 1800s many of the wealthiest merchants had moved to more salubrious areas further up the hill, leaving behind the large terraced houses for the newer middle classes. In the 1860s 153–155 Duke Street had been Mrs Blodget’s guest house. When she sold up, Dr Lewis purchased number 155, a handsome, wide, three-storey brick terraced house.

It is not known whether Matilda had a good relationship with her parents, or whether they were pleased with her marriage to Albert Cahn. However Sigismund must have been closer to his daughter Gertrude, for when he retired he moved to Southampton to live with her, eventually dying there in 1899.

Albert and Matilda set up home in Cardiff to allow Albert to continue his employment as a grocer. Exactly nine months after their wedding, following an extremely difficult birth, their only son, Julien, was born. It was thanks to the doctoring skills of her father that Matilda survived the birth. However, much to their chagrin there were to be no more children.

Albert Cahn was ambitious. He did not see his future in the greengrocery trade. He wanted a business that he could grow and leave as a legacy for his son. In 1885, he decided to set up a furniture business. Unconstrained by geography, he selected Nottingham as the ideal location, for being in the centre of the British Isles, it provided him with the widest possible distribution for his future sales. He moved his small family into a modest detached house at 12 Clipston Avenue, Nottingham.

Upon arriving in Nottingham, Albert was given the opportunity to run a cycle manufacturing business, C. Battersley & Sons. But he was not to be distracted from his main ambition and soon established his own, new business called the Nottingham Furnishing Company alongside Battersley’s. Success came quickly and by the mid-1890s Albert moved his family to the more grandiose surroundings of 11 Waverley Street, Nottingham, a large imposing house located on a wealthy residential street close to the centre of Nottingham. This was an area the Cahns felt comfortable in, surrounded by their middle-class Jewish friends. By 1899, Albert was only involved in furniture and was the proud owner of the thriving Nottingham Furnishing Company and the Derby Bank of Furniture. A contemporary described Albert Cahn as, ‘A man with extraordinary brainpower that astounded one very often’. Many years later such words were also uttered to describe his son.

Religion became the cornerstone of Albert and Matilda’s life together, both at home and in the wider Jewish community where the couple played an important role. Young Julien could not escape from an upbringing fully immersed in Judaism.

Immediately upon arriving in Nottingham in 1883, Albert Cahn sought out the thriving Jewish community. Within a year, he had become President of the newly formed, Nottingham-based Hebrew Philanthropic Society. There were a number of Hebrew Philanthropic Societies located regionally around the country. Albert had been inspired by the Liverpool Hebrew Philanthropic Society, an organisation that had been successfully assisting the Jewish poor, sick and needy since 1811.

A devout and charitable man, Albert was a natural organiser and leader and became a highly respected member of the community. By 1889 he was elected President of the small Nottingham Synagogue. His greatest input was as Chairman of the Building Committee formed to oversee the construction of a permanent, modern synagogue on Chaucer Street, the premises having been bought for £1,000.

In spring 1889, the foundation stone was laid for the Chaucer Street Synagogue. Albert Cahn presented a silver trowel to Mr Samuel, who laid the first stone with the ritual formalities. A vote of thanks was passed to Mr Cahn the President.

The synagogue was opened on 30 July 1890. The ceremony was beautifully described in Eight Hundred Years – The Story of Nottingham’s Jews by Nelson Fisher:

On a glorious summer day, three open carriages came into view. Rev Dr Hermann Adler (acting chief rabbi for his father) and Rev A Schloss sat in the first carriage each holding a scroll of law. Mr Albert Cahn and Mr Theobald Alexander, President & Treasurer also each holding a scroll sat in the second carriage. The synagogue was Moorish in design, seats in the body for 180 and 100 in the gallery. On behalf of the subscribers, Mr J Samuel presented a golden key to Mr Cahn with which to open the synagogue. Of handsome design, the key was inscribed with the initial words of the Ten Commandments in Hebrew, whilst in English there was a brief inscription setting forth the occasion of the presentation. Mr Cahn, in response, acknowledged the great kindness of his gift and his thanks that he had been spared to witness the accomplishment of their labours that day. He trusted that blessings would be showered on all connected with the Synagogue, which he concluded in formally declaring open.

Similar to his son, Albert Cahn was not only generous with his time, but also with his money. After the ceremony a reception was held by Mr and Mrs Cahn at the Masonic Hall, Goldsmith Street.

In 1892, Cahn became Chairman of the newly formed Chovevi Zion Association, a rapidly growing European Zionist organisation. This movement, which was the predecessor of political Zionism, was sponsored by Jews living in Europe and the USA, whose common interest in Jewish life, stimulated by the persecution of the Jews in Romania and Russia, led them to believe that it may be a good idea to create a Jewish country. The principal ideas were to foster the ‘national idea’ in Israel, promote the colonisation of Palestine and assist those already established, to make people aware that Hebrew was a living language and to better the moral, intellectual and material status of Israel. Critically, members of the association pledged themselves to ‘render cheerful obedience to the laws of the lands in which they live, and as good citizens to promote their welfare as far as lies in their power’. Although Albert may have wished for a secure country for Jews at large, he was utterly loyal and grateful to England, his adopted homeland.

Albert and Matilda kept a strictly kosher home, where milk was separated from meat and the Sabbath and all Jewish holidays were stringently adhered to. Albert did not dress in the garbs of the Orthodoxy as he wished to assimilate in England, but the beliefs and rituals in the home were never forgotten. As a child, Julien had no choice but to conform to his parents’ expectations and behaviour. He dutifully sat through the Friday night Sabbath meals, chanting his prayers in Hebrew. He attended Saturday services at the synagogue and Sunday morning cheder classes where the children were taught all about the religion and studied Hebrew. But from a very young age he began to question it.

Julien and his mother adored each other, but such adoration did not make for an easy childhood. Matilda smothered her only child with affection, indulging his whims and inadvertently encouraging his eccentricities. She was undeniably a rather strange woman. When guests came to her house in Waverley Street she would lock the door of the downstairs cloakroom so that they were unable to use the facilities. She had an obsession with health and cleanliness and did not want other people using her toilet. Matilda was viewed by many (particularly the servants who cared for her in her latter years) as a miserable woman who spent most of her days complaining and bossing staff around.

Julien’s childhood was uneventful and provided no precursory suggestions as to the successes he would achieve in adulthood. He attended a small private school in Nottingham for a few years, with the future Sir Harold Bowden, but thereafter was educated privately by a succession of governesses and tutors. Julien and Harold (of Raleigh Bicycles) became lifelong friends, bonded initially by being joint bottom of their class. In their adult years the men would spend happy hours fishing together on the lakes at Cahn’s future home, Stanford Hall. How ironic to consider that they were both to become the leading businessmen of their era. Bowden was sent to Clifton College to complete his education, but Matilda preferred to keep her son nearby. For the rest of his childhood Julien was tutored at home.

Home education allowed him plenty of time to indulge in his hobbies, childhood hobbies that were to mature into lifelong passions. Hours were spent reading The Boy’s Own Annuals and magazines, gaining inspiration for the magic tricks that he tested out on his mother. Magic was a common interest for young boys growing up in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. The popularity of amateur conjuring can largely be attributed to Professor Hoffmann, who published a book called Modern Magic that was serialised in the pages of Every Boy’s Magazine from 1876 onwards. Julien read each edition avidly. Every month he would wait in eager anticipation to find out the latest secrets of the professional tricks exposed by Hoffmann. Many of these were tricks performed by the world-famous Maskelyne and Devant. John Neville Maskelyne, born in 1839, is considered to be the founding father of the modern British magician. He was a prolific inventor of magic tricks and presented his illusions as magical sketches. By 1893, he was joined by David Devant. Maskelyne and Devant’s, just north of Oxford Circus, became the place for family entertainment. Between them they presented many famous illusions. Albert and Matilda took Julien to visit a Maskelyne and Devant show for his tenth birthday. The experience had a profound influence on him. He watched in amazement as the magicians took seemingly endless supplies of eggs out of an empty hat and passed them to the children to hold. His mouth fell open as a lady mysteriously walked through a wall and a donkey simply vanished in mid-air. For weeks afterwards Julien tried to work out how the magicians extracated themselves from a secure wooden box. Many of the illusions presented by these masters were to form the foundation of tricks that Julien performed thirty years later. As a young boy, whenever he had any spare pocket money, Julien would buy apparatus from the local magic shop and practise the magic tricks, patiently and diligently until they were almost perfect. But it was the grand illusions performed by Maskelyne and Devant that mesmerised him the most.

As he became older, Julien’s interest in magic diminished and was replaced by a passion for the game of cricket. When he was old enough to slip out of the house unnoticed, he would spend happy afternoons sitting under Parr’s Tree at Trent Bridge (an ancient elm named after George Parr, a famous Nottingham cricketer who regularly hit the ball into the tree) listening to the observations of his hero, Arthur Shrewsbury, and watching him play. Julien adored everything about the game. It is not known how or when he began playing himself. But he must have practised the rudiments of the game as a boy, for when he launched his own team in 1902, he included himself as one of the key players.

In the 1901 census, Julien Cahn, then aged 19, listed his profession as ‘Clerk to Piano Importer’. His father had every intention of employing his son in due course, but first he wanted him to gain experience in the ‘real world’, starting in a lowly employed position and working his way up. When Charles Foulds, owner of Foulds Music – a highly respected chain of music shops selling instruments and music – offered to employ Julien, Albert was delighted. Julien could learn the rudiments of retail and salesmanship and then, when he had proven himself to an objective outsider, Albert would welcome him into the Cahn family business, the Nottingham Furnishing Company. In fact, Charles Foulds was to become a firm friend, mentor and business associate to Julien. When Foulds Music teetered on the brink of collapse during the inter-war years, Julien came to the rescue, recalling with fondness the experience he had gained in his early years. He set up a piano division within Jays and Campbells, installing Charles Foulds and his son Arthur on the top floor of Talbot House to manage it along with the single Foulds music shop that still remains as a successful family enterprise today. Charles was heavily involved in music promotion and Julien was to become a key benefactor.

A love of music sustained Julien throughout his life. The first record of his involvement can be seen in Allen’s Nottingham Red Book of 1903, an annual book that lists all civic information, where it is noted that Julien Cahn was the Treasurer and Secretary of the Nottingham Aeolian Society, set up for the cultivation of the mandoline. No one recalls him playing the mandoline, although he did play the viola, badly. Some years later, he even had four songs published by Cary & Co., highly reputed music publishers. Julien composed the music and his friend Harry Farnsworth wrote the words, giving the pieces sentimental titles such as ‘England, Dear England’ and ‘My Heart is Faithful’. They did not become memorable hits, but do still lie in a published tome within the archives of the British Library.

Many years later, Julien Cahn talked about his early career with his eldest son, Albert Junior. ‘I had to sell pianos once. It doesn’t matter what you sell, if you can sell, you can sell.’

In 1902, Albert decided that it was time to offer his son a job. Julien had shown a particular aptitude for figures, and Albert needed someone to keep a discrete eye on his bookkeeper. Officially, Julien joined his father’s business as a junior furniture salesman, but it wasn’t long before he was spending all day on commercial rather than direct-sales activities. In fact, Julien had no particular desire to work for his father, but there was one significant advantage of working at Nottingham Furnishing Company versus Foulds Music. At the furniture business he could get hold of his father’s workers.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries it was commonplace for businesses employing a dozen or more workers to assemble their own cricket team. Play normally took place in the afternoon of an early closing day. This was particularly so in cricket-obsessed Nottingham. One of the big attractions for joining his father’s furniture firm was the chance to organise a group of men into a cricket team. At the tender age of 19, Julien Cahn cajoled sixteen of the Nottingham Furnishing Company’s staff to come together to play for the newly formed Nottingham Furnishing Company Eleven. During that initial year of 1902, the team enjoyed just two matches. Playing against the Liverpool Victoria Friendly Society on 21 August on the YMCA ground in Nottingham, they lost their first match. But a week later they played their second game on the Forest ground against a team put together by the Nottingham provision merchants, Furley’s. Cahn’s team scored their very first win.

Buoyed up by the success of his second game, Julien spent the next few months refining the team. He culled half of the 1902 players and went on an active recruitment campaign to find better cricketers to improve the chances of his XI in 1903. Not wanting to limit himself to the employees of the Nottingham Furnishing Company, he poached players from elsewhere. By the next season he had a posse of thirty-five men to call upon. As the team no longer comprised just Nottingham Furnishing Company employees, he was obliged to change the name of the team and so the players now found themselves part of the newly formed Notts Ramblers. Between 21 May and 3 September 1903, the Notts Ramblers played eight games, winning four and losing four. They played a number of local teams including Notts Unity ‘A’ team. This team comprised the founding members of the Nottinghamshire Cricket Association, one of the oldest cricket clubs in the country and still in existence today. Unsurprisingly, Cahn’s team lost.

Even in those early years, Julien Cahn’s personal averages were poor. In fact, in 1903 his averages were the worst in the whole of his team. But his inability to play well did not deter the young Julien. Intensely competitive by nature, his ambitions were clear from the outset. He wanted to have an outstanding team. Year after year he was determined to increase the number of matches played, attract better players and play against stronger sides. In 1904 the Ramblers played fifteen matches, winning nine, losing four and drawing two. This was a particularly auspicious year, for it was the first year that a member of the Vaulkhard family was to join the team. W.H. Vaulkhard was to become a firm friend and cricketing confidant, and it is believed that he was the man who originally suggested that Cahn should run his own cricket side. Later on, during the 1920s, recognising the cricketing talent of Vaulkhard’s four sons, Cahn was to mentor the boys and groom them for his team.

The Notts Ramblers grew rapidly in size year on year. In 1905 they won eleven of the fourteen matches they played, losing one game and drawing two. By 1907, they were playing against recognised teams and travelling around the country for games. Cahn had some notable players, including Goodall, a famous local architect, and Stapleton, the Nottingham reserve wicket-keeper. In 1907, the Nottingham Furnishing Company team was resurrected and they played a single game against Lenton United. The Furnishing team was, for that year only, Julien’s second team. By 1908, they were relegated to Cahn’s third team – for this was the year that the Julien Cahn’s XI was born. The Ramblers played nine games, Nottingham Furnishing played one game and Julien Cahn’s XI played one game against J. Holroyd’s XI.

Although the team created in his name lost their first game, this did not deter Julien. He concentrated on accumulating a smaller, more select group of players. The occasional friend or relation appears in the players list, such as B. Serabski in 1908 (one of Julien’s closest lifelong friends), but this was rare. Julien wanted only the best players. In 1910, the Ramblers played sixteen games, Julien Cahn’s XI played three games and the Furnishing XI just one. His players were now regularly scoring centuries. There were impressive performances against impressive teams. Matches took place against teams from Lincoln, Buxton, Uppingham, Spalding, Sheffield, Eastbourne and North Warwickshire, to name but a few. Over the next couple of years, Cahn’s teams travelled as far afield as Folkestone.

By 1911, cricket was the most significant part of Cahn’s life. He personally played twenty-five games and Vaulkhard played twenty-one. Cricket certainly seemed to be more important than work. Bearing in mind that some of these fixtures were two-day matches, Julien must have been out of the business and playing cricket for over six weeks.

During these years Albert was subtly encouraging Julien to become more involved in the business, take more decisions and be responsible for its growth. Julien rose to the challenges offered by his father and began to enjoy business life. He spotted an enormous opportunity in the development of hire purchase and persuaded his father to allow him to create credit terms for the business. He took control of the advertising and promotions of the company. Most significantly, he encouraged his father to begin acquiring other furniture businesses, the largest and most important being Jays. As long ago as 1910, as was evidenced in a typical advertisement carried in the News of the World, Jays were promoting themselves as ‘England’s largest and best credit furnishers’. By our modern standards, the adverts were polite and quite charming. They went on to state, ‘We have furnished over 250,000 homes on our famous system. May we furnish yours? Our furniture will give you pleasure and comfort for a lifetime.’ The Cahns’ furniture business was growing fast and by 1914 was one of only nine multiple-shop firms in existence in the UK.

The start of the First World War resulted in the instant demise of Julien Cahn’s cricket teams but business activities were deftly positioned to fill the void.

By his early thirties, Julien had taken over the reins of the Nottingham Furnishing Company but he was still living at home with his parents at 11 Waverley Street. While it was not uncommon to remain at home until marriage, Julien was certainly no young groom. Even Matilda recognised that it was time for her son to wed. The Cahns employed the services of a traditional Jewish matchmaker and before long Julien had been introduced to the young and exuberant Phyllis Wolfe.

Julien Cahn married Phyllis Wolfe on 11 July 1916 in the Bournemouth Synagogue. Phyllis was the daughter of Abraham Wolfe, who was born in Sunderland, Durham, in 1865. In 1881, he had been a boarder at 20 Alexandra Grove, Headingly Cum Burley, York, and was employed as a clerk in a loan office. Abraham Wolfe had three brothers, Jonas, Walter and Alec Wolfe. After marriage and the birth of four children (Jonas, George, Phyllis and Roland, the latter who died in childhood), the Wolfes moved to Bournemouth. When she married, aged 20, Phyllis had also been living at home with her parents at 61 Wellington Road, Bournemouth. Youthful and naïve, she had no idea that she was to embark on a life of wealth, status and excitement.

2

The Power of Philanthropy

Julien and Phyllis began married life at Papplewick Grange, a grand house for newly weds, situated in the delightful village of Papplewick, near Hucknall. It was a large and comfortable family house, with eight bedrooms and five bathrooms, a 30ft entrance hall, drawing room, dining room, study and library. The first few years of their marriage were happy and rather uneventful.

But by the early 1920s things were to change. Julien was to experience emotional turbulence such as he had never known.

After five years of marriage, Phyllis gave birth to their first son. Tragedy was to beset them during those late winter months of 1921. The baby died at birth. The infant’s name was never officially registered, but he was referred to as Roland, named after Phyllis’ younger brother who had died before his fifth birthday. Julien was particularly devastated by the death. Here was a man who had escaped the First World War unscathed, a man who had an easy life and was in command of every aspect of it. For the first time he was faced with an event over which he had absolutely no control. The repercussions of Roland’s death would affect him in both positive and negative ways for the rest of his life. While it propelled him to take a deep interest in infant mortality and to spend considerable sums of his fortune on improving conditions in childbirth, it also had a negative effect on his relationship with his future sons. He never became emotionally close to the boys.

Later that year, on 8 June 1921, aged just 66, his father, Albert Cahn, died suddenly of a heart attack. Matilda and Julien were devastated. The wealth he left them did nothing to appease their grief. By the time of his death, Albert was a rich man, leaving an estate of £260,397 gross (equivalent to £7 million today), net £189,505. The Nottingham Guardian carried the headlines: ‘Over a quarter million left by Jewish merchant!’ Although the financial legacy he left to his son was considerable, so was the responsibility. Julien was now solely in charge of one of the largest businesses in Nottingham. In previous years, he had always discussed his problems with his father, and was grateful for the wisdom and insight Albert provided. With the loss of his father, Julien’s life had, quite suddenly, become serious.

During these difficult years Julien Cahn’s bizarre habits became increasingly evident. As his wealth and status increased, so he began to care less about hiding his eccentricities. The most obvious was a compulsion to turn around in a full circle whenever he walked through a doorway. The reasoning behind this was never known. While many believed such behaviour was due to superstition, Julien was much too rational to be superstitious. This behaviour must have been a form of obsessive compulsive disorder. It caused various problems, most commonly when the person walking behind Cahn inadvertently found themselves walking straight into him, nose to nose. He even turned around 360 degrees when he got out of the rear of a car, typically leaning back in to pick up his Financial Times as he did so, in order to disguise the habit.

Eager to comfort her bereaved husband, Phyllis quickly became pregnant again and in February 1922 gave birth to the simply named Patience Cahn. Julien was to fall deeply in love with his daughter, a girl who inherited his dark features, a child whom he overly indulged for the rest of his life. Meanwhile, the pressures in Julien’s life continued to mount. He had moved his mother from her home in Waverley Street to Papplewick Grange.

Matilda Cahn was a demanding woman, controlling of all those around her. While most observant Jews didn’t work on Saturdays, they nevertheless visited the synagogue, said their prayers and socialised with friends and family. But Matilda refused even to get out of bed on Saturdays, announcing that it was the Holy Day, the day of rest – a commandment she took quite literally. Servants were expected to bring her food and drink in bed. Despite her difficult manner, Matilda had been devoted to her husband. After his death she lost interest in life. Within a year she was seriously ill and by the middle of 1923 it became apparent that she was dying of cancer. Towards the end of her life, she was so mean and bitter towards her carers that the regular nurses refused to help her and instead Julien found some nuns to administer to her needs during her final weeks. For a woman who professed to be so committed to Judaism, this was tragically ironic. She died at Papplewick on 1 December 1923, aged 63.

Phyllis’ life became easier after the death of her mother-in-law. She was now the lady of the house, a young woman with a zest for life. The staff adored her. She loved horse riding and the outdoors and had a coterie of young female friends with whom she played raucous games of bridge. She rarely interfered with the workings of the house and left all domestic decisions to the butler, an attitude that had been frowned upon by her late mother-in-law. She was loud and fun with a mischievous sense of humour that shone through, despite her deference to her older husband.

Julien had married well. Such willingness was important to him for he had a plan, and Phyllis’ compliance with it was essential for its success. In the years following his father’s death, Julien Cahn laid down the foundations for his climb up society’s ladder. His strategy was multi-stranded. It included the obvious – using his wealth to achieve recognition – and the less obvious – indulging in the ‘right’ pursuits. Hunting, philanthropy and the development of certain critical friendships were key ingredients. That he and Phyllis actually enjoyed these activities simply added to the rapid achievement of his aims.

Phyllis and Julien shared a passion for fox hunting. The Cahns were fortunate to be living in Leicestershire, the home of some of the best hunting territory in the country.

After the birth of Albert Jonas in June 1924, Phyllis was eager to return to horse riding and was thrilled when her husband was appointed Joint Master of the Craven Hunt based in Berkshire. This was the first time that Julien had used his money to buy himself status, but it was a subtly undertaken move, quite acceptable to his contemporaries. The hunt wanted a Master with funds and they wanted a Master who respected the ways of the countryside. Julien fulfilled both criteria and he rapidly garnered a good reputation among his hunting colleagues. The annual hunt ball was held at the Corn Exchange in Newbury. It was a fine occasion for the Cahns to show off their wealth and status. However, the location was far from convenient for the Leicestershire-based Cahns and Julien wanted to impress those closer to his home.

For several hundred years hunting was an integral and important part of social and rural life in Great Britain. In the late 1800s an estimated 50,000 people were involved in fox hunting, with about 150 people attending each meet. Whatever your opinion of hunting today, in the early twentieth century hunting was considered the natural and most humane method of managing and controlling foxes, hares, deer and mink in the countryside, and it was often the method particularly favoured by farmers. Hunting created a social mesh, bringing together communities and classes. It was considered such an important part of life that all of the local papers reported upon the local hunt’s activities. The weekly Loughborough Echo carried at least a paragraph or so on its local hunt, the Quorn. A change of Masters was deemed sufficiently newsworthy to be noted in the national papers. Each time Cahn took up a new Mastership it was reported in The Times. In light of this, it would be dangerous to judge the Cahns and their hunting compatriots by the standards of today.

During the first half of the twentieth century, to put the letters ‘MFH’ (Master of Fox Hounds) after one’s name provided immediate elevation in society. Only those who were truly the ‘pillars of society’ were Masters and upon attainment of such an honour, doors opened among the upper classes. A prerequisite for being an MFH was wealth. Perhaps the title could have stood for ‘Money Forthcoming Here!’, for that was what the Masters were required to do – fund the hunt.

There was never a shortage of candidates for vacant Masterships. So how did Julien Cahn, a little-known Jewish retailer, become a Master? The hunt committees sought gentlemen (or women, although there were few female Masters) of sophistication, possessing considerable intelligence, great tact and diplomacy – gentlemen who wanted to carry on the ‘Englishman’s best tradition’. If they lacked kennel experience or did not live in the county of the hunt (both categories into which Julien fell), they had to be ‘inspired by real keenness and enthusiasm, impelled by public-spirited anxiety to further the interest of sport and possess . . . an abiding love of the fox-hound’. It was his personality and commercial skills that endeared Julien to the hunt committees. He was gifted with all the attributes that Lord Willoughby de Broke considered a Master should have. Julien had tact, administrative talent, the ‘power of penetrating character’, the desire to take on responsibility and all other attributes that ‘form the essential equipment of a successful public man’. Skill in public relations was essential for the role, as the Master needed to gain the allegiance of landowners, great and small, to gain permission for riding over their land. Although most Masters were expected to have been ‘reared in the atmosphere and tradition of country life’, Julien must have managed to persuade the committees that he had a passion for the sport and while he was not brought up in the country ways, he had fully adopted them in adult life. He was certainly persuasive and deeply competitive. Another key attribute of the Master was ‘thick skin’. This Cahn seemed to have in abundance. Superficially at least, he cared little what others thought of him.

Mr Bromley Davenport, himself an MFH and MP, wrote:

No position, except perhaps a Member of Parliament’s entails so much hard work accompanied by so little thanks as that of a Master of Foxhounds. A fierce light inseparable from his semi-regality beats on him; his every act is scrutinised by eyes and tongues ever ready to mark and proclaim what is done amiss. Very difficult is it for him to do right.

The hunts were run as businesses, therefore commercial acumen in the Master was much sought after. Masters of the hunts would take on all financial responsibility and management. Should the hunt have any outstanding debts, the Master would have the responsibility for settling them. He also undertook financing and managing the breeding and rearing of hounds and keeping a stable of horses. The annual cost of running the hunt was considerable as it included payment of servants, horses, kennels-men, whippers-in and horses. It has been said that Sir Julien spent up to £50,000 per year on hunting in today’s money. Rather a large sum for a sporadic hobby.

Fortunately for Cahn, by 1925 the Burton Hunt was struggling. Based in Lincolnshire, which was somewhat nearer to their home, Papplewick Grange, the Burton Hunt’s subscriptions were down, the sport was bad and the Master, William Barr Danby, had resigned due to old age. So, when the committee learned that Julien Cahn was interested in the Mastership there was universal relief. Although he was yet to achieve his knighthood and subsequent elevation in society, Julien’s financial wealth and astute business acumen were renowned and he was welcomed with open arms. As is recalled in A History of the Burton Hunt – the first 300 years: ‘For nine seasons he used this income to the benefit of the Burton, but in return ran it as he wished.’

A considerable part of Julien’s enjoyment of fox hunting came from the dressing up. As fox hunting became fashionable, so the traditional hunting costumes became all the rage: a red coat, traditionally called ‘pink’, tight pants and riding boots. Dapper as always, Julien had all the necessary accoutrements. His tailors were engaged to produce his outfits and his boots, saddles and bridles were made to order, the leather buffed to a mirror-like sheen before every meet. In later years, Charlie Rodgers, Julien’s head groom, assisted by Wallace Addy, an assistant groom and great favourite with the housemaids, was responsible for ensuring that spurs and tack were polished, coats cleaned, hats brushed and smoothed. Everything had to be spotless, although five minutes into the hunt all was mud-splattered and filthy. Nevertheless, the dressing up and accessories added much charm to the whole exercise. Cahn frequently chose to be photographed in his hunting pink and the only portraits of him that exist today are of him in his hunting attire.

Phyllis Cahn, in her long skirts, was a confident horsewoman. She enjoyed riding, was proficient and, as was the custom at the time, rode sidesaddle.

In 1926, the year before their youngest child, Richard, was born, Julien Cahn, the Burton Hunt’s new Master, was received with ‘rapture’, his wealth, cricket and philanthropy preceding him. The previous Master introduced him as: ‘A Master who knew exactly how things should be done and intended to do them.’

Although the hunt was in financial difficulties, this did not deter Cahn. He was confident that, financially, he could turn the Burton Hunt around. He had sufficient funds to indulge in the hunt and right from the beginning intended to be its benefactor. Upon joining the Burton Hunt, he asked for a Master’s guarantee of £500. The Master’s guarantee was the sum of money that the Master expected to receive in return for running the hunt. Should the cost of running the hunt exceed that sum, the Master was personally required to foot the difference. For the first time, the Burton Hunt had asked tenant farmers and others whose land they hunted over for a subscription. Nevertheless, the money raised was £600 down on the previous year and a loan of £200 had to be taken out. On receiving his guarantee, rather than pocketing it, as was common practice, Cahn returned it to start a wire fund.

The wire fund was established to mitigate the dangerous effects of wire fences that were being erected across the countryside. As large estates were cut up, farms were purchased by tenants and smallholdings increased, so fields were divided by wire rather than the traditionally expensive to maintain wooden fences or hedges. Understandably, it was deemed more economically viable by many farmers to use wire.

Of course, wire fences were of great danger to the huntsman and it was in their interest for the wire to be removed. Julien described barbed wire as ‘a death trap’. Having put his guarantee of £500 towards the wire fund, he then gave another £150 in 1930. The money was used to cover the expense of removing wire at the beginning of the season, replacing it with rails or fences and then reinstating the wire at the end of the season. He used his administrative skills and powers of persuasion to set up a Wire Committee. Each member looked after two parishes and purchased the necessary timber for fencing. Julien was vociferous in his complaints if wire was left up. So as to encourage the growth and maintenance of hedges, in line with many hunts, the Burton Hunt instigated hedge-trimming competitions, with prizes being given to farms with the best-kept hedges.

While Julien claimed to enjoy the thrill of hunting, this was not strictly true. In fact, he was profoundly nervous of the pursuit. In a similar vein to his concern over getting hit by the cricket ball, he mitigated his risks of injury when hunting by employing a groom who would ride in front of him, warning of difficult places and cutting down branches if required. When they approached a difficult ditch, Julien would dismount, the groom would jump the horse over and Julien would remount on the other side. It has been commented that Cahn paid a great deal of cash not to jump fences in some of the best hunting counties in England. While his riding skills must have been mocked, few would have been openly critical for he spent a fortune ‘subsidising everyone else’s fun’.

Hunting was one tactic Cahn pursued for social acceptance; another method was philanthropy – a gesture altogether more flamboyant and instant in its results. Although he was a ruthless businessman, Cahn was also a generous benefactor. And he quickly realised that giving things away had other more important consequences over and above the feel-good factor. It brought him public gratitude, publicity and respect among the great and the good.

Over the years, many of Cahn’s philanthropic gestures were of a medical nature. His first public donation was not. It was the construction and donation of some almshouses in Hucknall, provided as homes of rest for elderly industrial workers. It is likely that Cahn gave these as much for the benefit of the local community as for the benefit of his friend, Sir Harold Bowden. On 10 February 1926, the Duke of York visited Nottingham as President of the Industrial Welfare Society. He was shown around the Raleigh Cycle Company’s works by Sir Harold Bowden. Afterwards he took lunch with the Bowdens and the Cahns and then visited the Hucknall almshouses donated by Julien. This was an enlightening experience for Cahn. He was invited to hobnob with one of the most important people in the country thanks to a donation.

Cahn’s second act of public philanthropy was medical in nature. Dr Henry Jaffé was Julien Cahn’s doctor and a close friend. From 1921, he and his colleague Rupert Allen specialised in caring for children with rickets, working in light treatment clinics in Nottingham. The UV rays emitted by the quartz lamps were believed to cure many skin conditions and be beneficial in cases of nervous excitability, sleeplessness and loss of appetite. A leaflet about the Hanovia Quartz Lamp (a typical lamp found in sun-ray clinics) explained that ‘irradiation simultaneously stimulated all the defensive processes of the body’. It was believed that the body was strengthened and so energised by the light that it was able to throw off the disease. As such, people believed that the light cured numerous illnesses, from gangrene and tuberculosis to rickets and anaemia. The medical profession and Cahn alike genuinely believed in the health-enhancing properties of this equipment.

During the mid-1920s, Cahn funded Jaffé and Allen to run a sun-ray clinic at 32 Heathcote Street, Nottingham. The services were offered at very low prices and sometimes free to those in need. However, in 1927 Cahn decided to withdraw his patronage, due partly to increased expenditure and partly because he wished to give his money to other causes. This was not a popular move. In a letter to the Mayor of Nottingham, the Revd Henry Canon Hunt of Nottingham Cathedral wrote that Cahn had received so many appeals asking him not to withdraw his support that he consented to keep the clinic running and had offered to hand over the apparatus to anyone who would carry on the good work. In March 1928, Julien Cahn gave over his clinic at 32 Heathcote Street to Nottingham City Council as a gift, on condition that the treatment was made fully available to poor people. Cahn equipped the clinic with the necessary apparatus and refurbished it with new furniture. Julien Cahn received much positive publicity and accolades about his donation in the local Nottingham and Leicestershire press.

After the deaths of his parents and firstborn son, Julien felt the need to resurrect his hobby of cricket to relieve some of the pressures of his daily life. Hunting was sporadic and occurred only in the winter months. The First World War was over and he had the money, even if he didn’t necessarily have the time, so in 1923 cricket began to feature once more in Cahn’s life.

While the Notts Ramblers and the Nottingham Furnishing Company teams were never to play again, the Julien Cahn XI was reborn in the summer of 1923, initially in a modest way. That first year they played only four mediocre matches. However, the numbers of matches played and the calibre of the players increased rapidly year on year. In 1924 they played twelve games, in 1925 twenty-one games and in 1926 thirty-four games. By 1927, the Cahn XI comprised outstanding individuals, playing an ambitious programme of fixtures around the country.

It seems extraordinary that a man could have such passion for his sports, participate in them, but show no skill or talent for them. Most incompetent players would accept their inability and minimise their participation to that of a spectator – but not Julien Cahn. A nervous horseman, he was nevertheless Master of the Hunt. An unskilled cricketer, he captained the leading private team of the twentieth century.

From these early years, Julien Cahn had ambitions to be part of the powerhouse of cricket, first in Nottingham and then at the Marylebone Cricket Club, Lords. By the mid-1920s he was already recognised as a man of stature, a major Nottingham employer and a donator of philanthropic gifts. On 18 February 1925, he was made a member of the Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club Committee, most probably elected by Mr Swain and Mr Goodall, two committee members who had played against his team in earlier years.