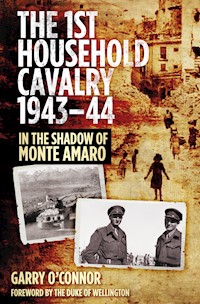

1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The mettle of the famous First Household Cavalry Regiment was tested to the maximum in action in the mountains of Italy in 1943–44. This book explores a largely undervalued and forgotten part of a costly and complex struggle. We directly experience what it was like to be there through the words of those who were. In late 1943 1st HCR was sent to Syria to patrol the Turko-Syrian border, it being feared that Turkey would join the Axis powers. In April 1944, 1st HCR was shipped to Italy. The Italian campaign was at that time well underway. During the summer of 1944, 1st HCR were in action near Arezzo and in the advance to Florence in a reconnaissance role, probing enemy positions, patrolling constantly. The Regiment finally took part in dismounted actions in the Gothic Line – the German defensive system in Northern Italy. Based upon interviews with the few survivors still with us and several unpublished diaries, there are many revelations that will entertain – and some that will shock. The 1st Household Cavalry 1943–44 is published on the 70th anniversary of the actions described, as a tribute to the fighting force made up from the two most senior regiments of the British Army and, in the words of His Grace the Duke of Wellington who has kindly provided the foreword, 'to gain insight into why such a war should never be fought again'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

DEDICATION

To the memory of John Ewart, and to all Household Cavalry men, past and present

The history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many and varied are those who helped in the writing and production of this book and to all of these my thanks and gratitude. Second to the diarists themselves and their families, and here in particular to those I have not mentioned in my introduction: the Astor family, for permission to quote from Lord Astor’s diary; and my thanks to Lord and Lady Carnarvon for permission to quote from The Carnarvon Letters 1943–1944, compiled by The Earl of Carnarvon.

This book would not have been possible without the generous cooperation of the Household Cavalry Regiment; my thanks to Harry Scott, the regimental Adjutant, and to Colonel Stuart Cowen the Commanding Officer, Major Paul Stretton, the Household Cavalry Regimental Secretary. I thank also John and Janine Lloyd, and Carl Johnson at the Household Cavalry Archive, Combermere Barracks, Windsor; the National Archives, Kew; the Ministry of Defence; the Imperial War Museum; the National Army Museum.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by His Grace The Duke of Wellington

Abbreviations

Introduction

Chapter One:

Prelude – The Terrible Saga of the Death of Cavalry Horses

Chapter Two:

Dramatis Personae – Our Main Witnesses

Chapter Three:

Cairo Days

Chapter Four:

Setting Sail for Naples

Chapter Five:

The March up the Hill

Chapter Six:

Arrival at Palena – Baptism of Fire

Chapter Seven:

A Miniature Stalingrad

Chapter Eight:

The Bitter Mountain

Chapter Nine:

The Fortunes of War

Chapter Ten:

The Slaughter Continues – The Winning Defenders at Cassino

Chapter Eleven:

Epiphany – But Others do Time

Chapter Twelve:

Femina Morta

Chapter Thirteen:

Games with a Goose

Chapter Fourteen:

U.S. Sangri-La Versus A Squadron RHG

Chapter Fifteen:

The Last Battle

Epilogue

Appendix:

List of Officers who served with the Regiment in Italy

Select Bibliography

Plates

By the Same Author

Copyright

FOREWORD

by His Grace The Duke Of Wellington KG, LVO, OBE, MC, DL

This book pays fitting tribute to the surviving officers and men, to those no longer with us, and indeed all members of the Household Cavalry Regiment, for the values and traditions it celebrates. Full of vivid detail and humour, it will appeal to everyone interested in war and conflict, to serving personnel the world over, but also to those keen to read accounts of the British Army in Italy in World War Two. I was commissioned as a second lieutenant (or Cornet) in the Royal Horse Guards in 1940 and served in the First Household Cavalry Regiment during the African and European campaigns. I am delighted that the book includes my own contribution, and I was fascinated to read for the first time the diaries and accounts of my fellow officers of our engagement in the Italian campaign of 1943–1944. I had no idea such vivid records were being made on a daily basis. The book binds together material from these diaries, interviews with the author, official and historical accounts and personal letters to home, and shapes a gripping narrative of the campaign we fought through ravaged and starving Italy, which had in 1943 changed sides, and was then subjected to cruel and savage Nazi reprisal. Here, therefore, largely told and taken from the mouths and recorded words of the few survivors who are in their nineties, among which I figure, as well as those who have gone, is the chance to share again our youthful adventures in the line, our hazards and tribulations, and gain insight into why such a war should never be fought again.

ABBREVIATIONS

1HCR

1st Household Cavalry Regiment

2i/c

Second in command

AA /Ack Ack

Anti aircraft

A/C

Armoured Car

ADC

Aide de Camp

AEC

Army Education Centre

AOC

Air Officer Commanding

AOC

Air Operations Centre

APM

Assistant Provost Marshal

AP

Armour Piercing

AT

Anti tank

Carp L

Carpathian Lancers

CB

Counter Battery

CIH

Central India Horse

CMOs

commanders

CO

Commanding Officer

COH/CoH

Corporal of Horse

COH

Corporal of the Horse

COMNS

Communications

Cpl

Corporal

Det Pol Eng.

Polish Engineers

DF

Directed Fire

DIV

division

DPO

Divisional post office

FA

Field Artillery

FANY

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

GHQ

General Headquarters

GSO

General Staff Officer

Infm

information

IO

Intelligence Officer

LAD

Light Aid Detachment officer

LG

The Life Guards

MC

Medical Corps

MG

Machine gun

MP

Machine pistol

MO

Medical Officer

MP

Machine pistol

MP

Military Police

NCO

Non Commissioned Officer

OP

Observation Post

PW

prisoner of war

POW

prisoner of war

RCM

Regimental Corporal Major

RSM

Regimental Sergeant Major

Recce

Reconnaissance

REME

Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

RHG

Royal Horse Guards

RHQ

Regimental Headquarters

RQCM

Regimental Quartermaster Corporal Major

SCM

Squadron Corporal Major

SO

Signals Officer

Sqn Ldrs

Squadron Leaders

Tp

Troop

Tpr

Trooper

TSMG

Thompson Sub machine Gun

UC

Unclassified

WO

Wireless Operator

WT

Wireless telegraph

YR

Yeomanry Regiment

INTRODUCTION

Nothing better sets the scene for the Second World War probing and pursuit, reconnaissance role of the 1st Household Cavalry Regiment, a composite of The Life Guards and The Royal Horse Guards – the British Army’s two most senior regiments – than this entry in Lieutenant M.H.A. Fraser’s diary:

May 8, 9, 1944. The Bosch really are devils. I was one of the first patrols to enter Palena after the Bosch left it on the night of May 7th/8th so found it almost exactly as they left it. About 80% of houses are useless, many have walls standing but others also are completely flat. Much of this is due to shelling, but before they left the Germans blew up many of them with mines. The mess inside the houses is terrible. It looked just as if the Germans had walked into them, turned everything upside down, taken everything they wanted and then pushed off. Several houses reek of dead bodies under the rubble.

The Germans, tenaciously defending from the heights of Monte Amaro, or Bitter Mountain, of the Maiella Range in central Italy, had not gone far, and were to make it as uncomfortable as they could to stop the Regiment moving forward.

Previous to landing at Naples, the Regiment had since late 1943 been leisurely encamped in Egypt in the heat of the desert, training and taking part in mock battles. In April 1944 it embarked to go into the line in the inhospitable Apennines, where, advancing through the ‘scorched earth’ of the German retreat, it had to abandon its armoured cars and proceed on foot.

The Regiment became caught up in a very different type of conflict than in its earlier engagements, and these now involved civilians and townships, and a largely unseen enemy. The aim of the following pages is to show what this conflict was, and how the officers of the Regiment magnificently fulfilled their duty while observing the highest rules of behaviour and commitment,

Hearing them talk in their own words, we get under the skin of these young officers, learn what their characters are, where they come from, how they look, speak, act – and how they feel about the death of their comrades, the dangers they face, and the conditions they live through. Their insights and dramas multiply in depth and interest. They inhabit a very small corner of the total war, a very personal one, full of charm and humour, yet they are in the shadow of untold horror and destruction. Even here, they find unexpected touches of comradeship and coincidence – as well as danger.

Compared to the mass engagement and carnage of millions in the various theatres of the Second World War the account is very human and personal. They are generally cheerful and genial figures, from ‘Wispy’, their Commanding Officer, down through the ranks: as ‘Porchey’ (Lord Porchester) says of John Ewart, he ‘is laughing as usual’– ‘Happy Warriors’, as Evelyn Waugh subtitled his Officers and Gentlemen. We discover and engage with them at a moment just before the tipping point of the war, both in Italy and Europe at large, leading to victory.

To the end this cohesive unit, in the midst of the chaos and uncertainty of war, strives to preserve its curious, not to say eccentric but certainly unique, identity.

First, by way of introduction, is a curious and heartening tale, which is more than tinged with sadness: that of how I came to be involved in this project, to begin with by listening to the memories the officers had to share with me; and second, by reading the tens of thousands of words of their accounts and diaries, with a view to thinking how a book could be made out of them that might appeal not only to serving and former officers and men of the Regiment, but also to members of the armed services generally, and readers interested in ‘living history’ from the last survivors of the Second World War.

John Ewart was one of the very young lieutenants involved, and until he died at the age of 87 on September 6, 2012, a landowner and businessman residing just outside King’s Sutton on the Northamptonshire–Oxfordshire border where I live with my wife Vicky and family. While Vicky and I had met John many times socially, he was of our parents’ generation, and was a man of many interests; businessman, farmer, landowner, and long-standing County Councillor, as well as keen foxhunter and yachtsman. He was very patriotic, a Tory and a devout Roman Catholic who regularly attended the local Catholic Mass in our beautiful Anglican church in the village.

John had always been an avid reader, especially of biographies, history and books about politics, and had read several of my works. In his mid-eighties he had given up hunting and sold his estate in Devon and lived permanently at Astrop House, his Georgian manor with grounds designed by Capability Brown, which he bought in 1952.

One day he invited Vicky and me, his daughter Lavinia and Charles, her husband, and his niece Victoria, a researcher, to dinner to meet two more ex-lieutenants of his age, Herbert du Plessis and Malcolm Fraser, who served with him in the 1st Household Cavalry Regiment in 1943-44. All three, we had been briefed earlier, had kept diaries during that period, although, for the reason that they might fall into enemy hands and give away vital intelligence, such a practice was forbidden under military law. If discovered the diarists could have been arrested and tried by court martial.

Herbert and Malcolm, as well as John, exchanged with us fascinating memories of that campaign and subsequently I received Malcolm’s diary, which had been transcribed, as well as a memoir by Herbert based on his own diary. John was very keen to know what I thought of the material and if I could make a book out of it. He had meantime amassed a challenging and far-ranging collection of books about the Regiment and the Italian campaign from the time he joined until the end of the European war in May 1945, as well as regimental memorabilia and histories.

We then set out, with Victoria his niece doing the research, to see if any of the other young officers at the time who were in HCR – and especially in 1st or A Squadron – had written diaries or letters, or were still alive and would be happy to be interviewed. Victoria tracked down addresses of those few more who were still with us, or, if deceased, their relatives, to ask if there might be any material we could draw on.

John, Victoria, and I held frequent meetings to discuss the project and we soon amassed, in the farm office at Walton Grounds, King’s Sutton, a veritable treasure, a rare enclave of living history, which had not been brought to public view before.

I still felt unsure how to approach and shape the material we had gathered. John was most reluctant at first to have his own diary, which he kept only from joining the Regiment up to October 1944, typed by his devoted secretary, Heather Rawden, and it was only after repeated requests that he consented.

By extraordinary coincidence, three more diaries concentrating just on that one year came unexpectedly to light after I had written the synopsis. The first was that of Lieutenant John Shaw, suggested to me by Lieutenant-General Sir Barney White-Spunner, author of Horse Guards, his magnificent account of The Life Guards and The Blues and Royals. The second was the prison diary of Ian Van Ammel, whom I interviewed before his death in July 2012. The third, that of Gavin Astor, came our way only at the very last moment, in November 2012, by when the book was well underway.

In addition, His Grace The Duke of Wellington, then Captain Marquess Douro, generously provided a written account of his earlier desert campaigns and agreed to be interviewed. I also interviewed the Marquess of Anglesey, then Lieutenant Earl of Uxbridge.

I cannot do justice to the unflagging and generous enthusiasm of John Ewart, who drew on a wide network of friends and colleagues and put heart and soul into the creation of this book. It was very much his book from the beginning, from his approval of the synopsis and his dedicated overseeing of all stages as it progressed, until the time of his death in early September. All during the winter of 2011–12 he was in and out of hospital, and it was touch and go whether he would survive until the summer. Even so, he was determined that the book should be written, and overjoyed when we found a publisher in The History Press. His next concern was the launch of the book, for which an unbelievable amount of organisation was mustered even before I began to write.

He was always very concerned that I should have complete freedom with the material and take any liberties that I might want to make it engaging and appeal to the widest possible readership. Quite often I would answer when he queried something he feared might be a bit risqué, ‘We can’t leave that bit out, it’s what will help sales’ – while of course I was not entirely sure I was right, but he trusted my instinct and experience. And what he wanted, being a businessman, was for the book to sell as many copies as possible. He would ask, ‘How many copies are going to be printed?’– again even before I’d started.

I must emphasise that this is wholly my own work, in that I must be held responsible for the choices of inclusion or omission and the errors, judgments and opinions that are to be found here. Victoria Ewart and I have done our best to ensure factual accuracy, to respect copyright, and consult those whose material we have drawn on, or interviewed, and obtain permissions where necessary. There are acknowledgements as well as a bibliography at the end of the book.

I was very glad that I could show to John in rough form the work in progress only a fortnight before he died, and he was able to browse through and enjoy it for several hours. I believe he was very happy knowing that it would be finished – in time for the launch!

To him therefore my heartfelt thanks, and hopes that this book fulfils his dream and expectation, and embodies his warmth, his love of life and generosity, his honesty, and – one thing utterly out of date today – his modesty.

I have generally kept to the original spellings, punctuation and vocabulary, changing them only when they might result in misunderstanding or obscurity.

CHAPTER ONE

PRELUDE – THE TERRIBLE SAGA OF THE DEATH OF CAVALRY HORSES

In World War II it usually took months to go to and come back from war. Today a soldier can go out on patrol and kill someone or have one of his friends killed and call his girlfriend on his cell phone that night and probably talk about anything except what just happened.

Karl Marlantes, What it is like to go to war

The composite regiment of Life Guards and Blues, now called 1st Household Cavalry Regiment, had set out with its horses to Palestine in January 1940 travelling across France through Marseilles and then crossing the Mediterranean, during which the horses ‘had a miserable time and suffered very badly’, according to the Duke of Wellington in conversation with the author, then listed in records as plain Lieutenant A.V. Wellesley, and known among his circle as Valerian. ‘This was the last time horses were ever used in the British Army.’

The horses – quite extraordinary to think in this day and age – but in 1939 we had three regular regiments of cavalry with horses and eight yeomanry regiments, I believe about 10,000 horses and 15,000 men. The Greys and Royals were already in Palestine. This was the time of the Arab rebellion, and they had done very well in the operations particularly in the rural areas and it was felt if we were going to use cavalry at all it would be best to send them to the Middle East. They decided in May or April the Regiment, plus the remains of the rest of the cavalry regiments less the Greys and Royals who were already in Palestine, and all the horse yeomanry regiments, should go to the Middle East. They left via France from Marseilles and landed in Palestine.

They were optimistic the war would last a short while before they went. This was 1940, the ‘phoney war’, and there had been no engagement with the Nazis. They did not think they might never see their sweethearts or families again, and even if at the back of their minds there were fears, they did not dwell on them.

Aged 25, Lt Wellesley, was a young man of gentle aspect but as you might expect from the great-great-grandson of the General who had beaten Napoleon, was not given to morbidity or introspection. Wellesley was third in line to the title of Duke. Like his illustrious ancestor he would speak his mind directly.

I sense at once in his presence seventy-two years later, when he was 97, an awareness of the cost of war, perhaps echoing the former Duke who said, ‘Well I thank God! I don’t know what it is to lose a battle, but certainly nothing can be more painful than to gain one with the loss of so many of one’s friends.’ His Grace’s own similar words are ‘Every day we had to deal with what came our way, and we didn’t stop to dwell on our problems. You were never sure what would happen the next day, which of your friends would be gone, forever. It was all part of the job.’

Valerian Wellesley did not travel out with the horses. He went two or three months later, with the first reinforcements. He took a draft of 37 men on the Empress of Britain from Liverpool. They sailed over two months to get to the Near East because by that time the submarines were very active.

The great thing about the Empress was that she was equipped for leisure cruises before the war so whisky was 1d a glass, and it was far from being ‘dry’. We had around 2-3000 men – reinforcements for all the regiments out there, not just the cavalry. We sailed out into the Atlantic and virtually across to the West Indies, and returned and came back to Freetown on the West Coast of Africa where we refueled.

Lt Wellesley was in charge of the guard policing the vessel, whose passengers included 50 Queen Alexandra nurses, ‘No improper behaviour on the deck – or in the lifeboats’ was his responsibility, which meant, ‘I couldn’t get up to anything myself.’ No one was allowed ashore here, but the Empress was solicited by hawkers on little native boats in the harbour peddling sex and combustibles.

East now into the South Atlantic, docking at Cape Town, where everyone went ashore. The people in Cape Town were wonderful to us, and we spent 3 or 4 days there. There was an elderly cavalry captain from WW1, who was ship’s commandant, who said to me, ‘Look I want you to go and liaise with the Cape Town police and go round all the night spots and make sure no one is left behind because we have to sail at 5am tomorrow morning.’ So I did this and had to visit every brothel and club with the Cape Town police who were quite a tough lot. As a young officer I was rather shocked by some of the behaviour. I reported back to my ship’s commandant at about midnight and said I couldn’t find anyone, so he said well done, everyone was on board, and we sailed up through the Suez Canal to Port Said. It was pretty awful in the Indian Ocean, incredibly hot and before the days of air conditioning. Just one man died of heat stroke – maybe two. Then from Port Said we went by train up to the Regiment.

Wellesley took his thirty-plus intake to Tulkara where 1HCR had its base. On the night of arrival his Squadron Leader arranged a little ‘welcome’ party. They were having dinner at a long table in the open air when ‘suddenly there was a lot of firing and it seemed as if we were being ambushed.’ High jinks abounded: they were part of the ethos, so they got their own back on the commander by lacing his gin with a chemical that turned his urine bright green.

Valerian shot duck on Lake Haleh, later drained by the Israelis but then inhabited by a race of Arabs said to have webbed feet and to be immune to malaria. He took part in exercises. ‘I was in a Forward OP when the rest of the Regiment was in the Jordan valley, Plain of Esdraelun, a resounding Biblical name. The whole of the 4th Cavalry Brigade, which included 2000 horses, advanced as an exercise. I watched this enormous force advance and charge – such an amazing sight which never happened again, for this was the last of the great cavalry exercises.’

Early in 1941, Valerian, who had patrolled on horseback, heard they were to be mechanized, and that all the horses over 15 years old were to be put down in our camp areas and the remainder would be sent to horse transport companies in Egypt. Later, many went to Greece for the campaign there and were lost to the Germans. In December at Beisan in the Jordan Valley he was told they were to be issued with wooden-bodied Morris 15 hundredweight trucks – an armoured car regiment without the armour – so functioning, as they were to in Iraq and Syria, as motorised infantry.

The tactics were not easy to define. When our horses left us we were told our future role was that of an Armoured Car Regiment – a role we welcomed. In general terms the main role of our A/Cs is armoured reconnaissance. Assuming that a formation such as a division is advancing in a mobile operation, it will be preceded by an A/C formation whose duty is to cover and protect forward units, report on enemy movement, probe for weak spots in enemy defences and if possible push aside enemy forward units. In a static situation an A/C Regiment’s main task is forward observation to give early warning of enemy movement and intentions. In a withdrawal an A/C Regiment may be asked to cover withdrawal of, say, our own infantry, or other formations and delay and harass forward enemy movement.

On one especially sad and gruelling day, Valerian had to separate the horses which were older than fifteen from the others.

We shot them with a revolver or with a humane killer with a bullet in it. You drew a line from the ear to the eye and where it met that is where you put the bullet. The bullet in this case was either from a pistol or a humane killer. I think I used my pistol because there were not enough humane killers around.

It was a horrible business I had to do with 14 old horses in my troop. Those lovely old black horses had taken part in all the great state occasions of the last ten years, including the 1936 Coronation. There on a bleak Palestinian hill they were left to be eaten by wolves and jackals. As I look back it was one of the most horrible moments of my life.

Then we spent that winter in Beisan in the Jordan valley until February, when we got these ancient and wooden-bodied Morris trucks and we did our best to do manoeuvres. Suddenly we were on a big exercise. The Germans had managed to infiltrate a certain Dr Grobba into Iraq and he effected a coup d’état in which Raschid Ali, a pro-German soldier, took over, and suddenly the British Government woke up to the fact that in Iraq they had a hostile regime who no doubt could be a great nuisance to us with regard to our position in the Middle East, and also astride oil reserves, so they looked around and couldn’t find anyone to send over apart from the 4th Cavalry Brigade that was in the Jordan Valley. Everyone thought at the time, even the legendary leader Colonel Glubb Pasha, that British power in the Middle East was about to collapse. The first target of the Axis plan was the tactically important RAF base at Habbaniya, where flying boats from England used to land on their way to India.

The base was a huge complex of power plants, workshops, water supplies, native cantonments and armed services and civilian messes that had cost millions — a self-supporting town of over 10,000 inhabitants, of which 2,200 were fighting men. Built by British contractors in the desolate Iraqi desert next to a huge and choppy expanse of water, with streets named Kingsway and Cheapside, and even a Piccadilly Circus, in March 1941 its garrison faced the 9,000 men and 50 guns of Raschid Ali’s besieging army.

They decided to send us across the desert to Iraq to relieve the base where British families had fled from Baghdad, where hundreds of these subjects had earlier taken refuge. The first thing the renegade force did was to try and take over the base, which they failed to do, as the RAF levies were very gutsy, showed complete contempt for danger under fire, and fought them off. We were dispatched in our wooden trucks across the desert to relieve the siege.

The levies, locally raised forces, mainly Assyrians but also Kurds and Yazideees, were fanatically pro-British, and worshipped the King and Queen. They lived in small huts, performed war dances and each had an average of six children. The Germans had use of airfields in Syria, which was occupied by French Vichy troops fighting on the German side. The forced ‘march’ to relieve the garrison was unforgettable.

The searing heat of well over 100°F in the shade seemed to bounce off the black volcanic rock which covered much of the desert and, combined with clouds of dust and a shortage of water, made this journey in old open 15 cwt Morris trucks a pretty testing one. To my considerable annoyance my dark glasses blew off in a sandstorm, which to begin with caused me great discomfort.

Our daily ration of water for the journey for six men was approximately one gallon. These were carried in Chargules, which were canvas bags that theoretically allowed a small amount of water to evaporate and this kept the contents cool when hung from the side of the truck. Initially we didn’t think much of them as they leaked quite a lot but our old line cavalry reservists, who had served in India, assured us that when covered in mud and sand they worked quite well. This proved to be the case as they got a coating of sand as we drove along in clouds of dust.

They travelled for four days at something like a hundred miles a day until they reached Rutbah Wells inside Iraq and within striking distance of Habbaniya and Baghdad. Here they were bombed ineffectually by a single German ME 110 fighter-bomber, living proof that the Germans were using bases in Iraq and Syria.

One evening Valerian spotted several coveys of sand grouse, flying into a water hole: ‘So I dug out the 16 bore gun I carried throughout the war in a saddle holster, and made my way there. I managed to shoot a brace, which I carried back in triumph intending to have them for breakfast. Alas, such was the heat they were putrid by the morning. I should have gutted them immediately.’

On the way, at Mafraq, the force was joined by Colonel Glubb Pasha’s Arab Legion, provided by King Abdullah to support the British. As Wellesley stood watching refugees with their household goods and livestock coming in a steady stream down the road from Baghdad, a voice at his elbow said, ‘Sad sight, isn’t it?’

Beside me stood a short man in khaki drill with medal ribbons and impressive badges of rank with which I was not familiar. He had a pronounced cleft in his chin and on his head he wore an Arab Khuffiah. I realised I was talking to the great Glubb Pasha, commander of the Arab Legion.

Behind him was a group of what 1HCR called ‘Glubb’s girls’. They spoke a while until he moved off into the desert. While memories of Lawrence of Arabia had faded in the Arab world, Glubb was the present legendary figure who hated his sobriquet ‘the second Lawrence’. Arabs called him ‘the Father of the Little Chin’, because his jaw had been partly shot away in the First World War and his teeth had grown together to look like a beak. He was not one to chat, Wellesley noticed, but so revered was Glubb that dozens of Arabs, often sheiks, just liked to spend time in his presence in silence.

The Legion consisted of Bedouin tribesmen from the Badia desert, warriors with black ringlet hair and lean, dark, hawkish faces, who wore long khaki drill-robes festooned with belts of ammunition. Each carried a rifle, an evil-looking dagger and a pistol, while their headdresses were red-and-white check Khuffiahs.

The Legion’s task was to protect the long and open flanks from marauding tribesmen and dissident bands of rebels, notably that led by Fawzi Kawachi, a well equipped force of some 500 men. Fawzi operated with French support from Syria. Fawzi was a well trained leader who had served as an officer in the Turkish army in the Great War and commanded, as an able tactician, an effective mobile force. He was a cruel and barbaric foe: he poured petrol over his captives and burnt them alive, or stripped them and turned them loose in the desert to die. Fawzi was to prove, Wellesley said, ‘a real thorn in my flesh’.

When they arrived in Habbaniya the Regiment found the besieging Iraqis had fled to Baghdad, so there was no resistance. That same night, relief came to the men in the Wadi. Near the lake, Valerian never forgot the sight of ‘hundreds of men tearing off the clothes they had been wearing for the best part of a very hot and exhausting week and racing stark naked, like a crowd of excited schoolboys, into the cool waters of the lake’.

The RAF had a troop of old Rolls-Royce engine A/Cs equipped with First World War Vickers machine guns. They were used by the RAF for internal security purposes in the lawless tribal areas of the desert near Habbaniya. This troop during a routine patrol managed to get two armoured cars stuck in soft sand. Fawzi Kawachi and his band captured and removed one of these cars.

A troop of B Squadron 1HCR, sent to recover the other car and rescue the crews, was unable to move it, and Valerian went with his troop with a LAD (light aid detachment recovery vehicle) to get the A/C out and reinforce the B Squadron troop, as Fawzi was expected to return.

Valerian’s troop combined with the B Squadron troop to extricate the A/C from the soft sand and took it back to Habbaniya. On their way an RAF Gloucester Gladiator looking for its RAF armoured car, saw them and strafed the recovering party before the pilot realised his mistake, killing a man in B Squadron.

That in Fawzi Kawachi Valerian had an identifiable enemy, a very personal figure who nearly obliterated him, was to be shown not long after, when Fawzi and his dangerous irregulars escaped the fall of Baghdad to the relieving British force and moved to Abu Kemal on the Syrian frontier.

Valerian, with A Squadron under Major Eion Merry, set out in pursuit. Unfortunately, they had none of ‘Glubb’s girls’ with them to decipher intelligence. They had reached the Euphrates from high ground, which squeezed them close to the riverbank, when Valerian looked towards the crest of the hill on his left and saw