1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

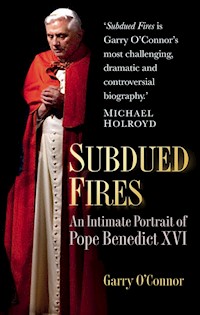

Omaha Beach, June 6, 2004. A delegation sent by John Paul II from the Vatican to commemorate the 60th anniversary of D-Day is headed by Joseph Ratzinger, a former Nazi youth who, while resident in Rome for the previous 23 years, is known as 'The Panzer Cardinal'. Ratzinger insisted on being at the commemoration. Garry O'Connor's biography begins here. And what is revealed from that point is an extraordinary figure, a man who a year later would be Pope, something no one predicted, at the age of 78. How did 12 years of Nazi rule affect the young Ratzinger? Did it inform his stand on religious persecution; famine and poverty; war and its consequences; climate change; stem-cell research and biological engineering; marriage and the family; abuse by priests; abortion, contraception, women priests, homosexuality, declining ordinations and Church attendance in Western Europe? And is it relevant to his astonishing resignation in February 2013? There is no one better qualified than Gary O'Connor, author of the international best seller, Universal Father: a Life of Pope John Paul II, to tell this remarkable story.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Prologue: Unlikely Bankroller

PART I

THE BOY FROM BAVARIA

1 Shadowland or Fairyland?

2 The Pied Piper of Lower Bavaria

3 Hiding in Cassocks from the Long Knives

4 The Dying Fall: Kirchenkampf

5 The Traunstein Idyll

6 Religious Czar and Two-Way Kardinal

7 Did They Resist Intimidation?

8 Complete Innocence and Sexual Continence

9 High Interior Exaltation

10 A Contrast of Two Adolescents

11 Example to the German Bishops

12 More Dissolving Battalions

13 Strange Meeting If True

14 Frisch Weht Der Wind Der Heimat Zu

15 A Conflicting Message

PART II

THE COVERED-UP CHURCH

16 Theology First, Life Second?

17 Rapid Advancement

18 The Panzer Kardinal

19 Election as Pope: The First Year as Benedict XVI

20 12 September 2006

21 Year Three

22 Chill Winds: Family Matters in 2009

23 If You Keep Quiet I Won’t Say Anything

24 The Mimetic Double of Celestine V

25 Is the Light Dark Enough?

26 The Interpretation of the Time

27 The Greatest Drama of the Pontificate

28 Il Grand Refiuto

Select Bibliography

Plate Section

About the Author

Also by Garry O'Connor

Copyright

Acknowledgements

I have to be brief. I have been writing parts of this book from the time in 2005 I finished Universal Father. I must acknowledge with deep gratitude all those who have helped or contributed to its writing and production. It was only commissioned in mid-February 2013, and went to press on 15 March. First of all, I thank my friends in, and members of, the Church, as well as other friends of a definitely non-religious ‘denomination’, too numerous to list at the present time. Without their comments and opinions, as well as information about Pope Benedict over the years, I would have got nowhere. I thank Michael Holroyd, for reading a draft; my agents Julian Friedmann and Tom Witcomb, and their German reader Julia Reuter, who commented on drafts and some early chapters, and to Jackie Bradley for help in various ways. My thanks are due to the Press Association for pictures and their captions.

I thank the many writers of source material I have drawn on, especially Peter Seewald for his interviews with the Pope; as far as possible, I have referred to as many sources as I could in the text, and listed them in the Bibliography. I must stress that the opinions and interpretations I place upon them are entirely my own.

I must especially thank all those involved in this extraordinary effort of publishing. My good fortune was to have Martin Noble edit the final text over an extremely short time, which he did with his usual enhancing and perceptive skill. At The History Press, most of all I thank Shaun Barrington, who has engaged with the book at every stage of its development with boundless enthusiasm and energy, and with whom I have enjoyed working enormously.

Last, but not in any way least – and really they should be first – to Vicky and my family, whose opinions and attitudes I have done my best to incorporate.

Foreword

6 June 2004

Omaha Beach, Normandy, scene of the first landings of the Allied invasion of mainland Europe in 1944, which is to lead, together with Russia’s advance from the East, to the overthrow of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. Steven Spielberg has replicated with graphic impact the carnage unleashed on the beachheads in his film Saving Private Ryan.

The Vatican delegation, sent by John Paul II to commemorate the invasion, is headed by Joseph Ratzinger, an alleged former Nazi youth who, while resident in Rome for the previous 23 years as Prefect for the Congregation of the Faith (CDF, formerly the Holy Office, formerly the Inquisition), is known generally in the media as ‘The Panzer Cardinal’, or ‘God’s Rottweiler’.

This is the German sheepdog breed which goes back to Roman times, famed for its savagery, brutality and ugliness, but today in Ratzinger’s native state of Bavaria legally subject to muzzle and leash control.

The 77-year old, white-haired cardinal, small in build, stooped, gracious and mild in manner, hardly lives up to this description. For many years, since 1981, he has been the papal enforcer of worldwide Church discipline, often at the cost of outrage and hostility, and the Pope’s closest colleague.

Ratzinger is in Normandy from his own choice, and while ever the patriotic German, he finds his presence here painful. Born in Upper Bavaria, near to the border with Austria, he looks more to the old cosmopolitan Austro-Hungarian Empire, with its former border only a few miles away from his home, than to the narrowly nationalistic Prussia of Frederick the Great.

As a gesture of reconciliation he has insisted on being at the scene of the Allied landings, symbolic of the beginning of the end of Hitler’s power.

What does Ratzinger, standing in that beach-hood ceremony in Normandy, remember from his own childhood – passed often in mortal peril in the darkest years of his country’s history?

He believes, and has said, that it is crucial to remember the past. He remembers, and as such is an apt testifier to the Greek word for truth, which is aletheia* – literally ‘not-forgetting’.

His own memories are of a rich and warm childhood in a pious, respectable, even rigid household. A safe childhood. But there are significant omissions which were to have an important effect on the future, both his own and the world’s.

† † †

The life story of Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI (April 2005–February 2013), is a supreme example of the evolution of an outstanding intellect, combined with an unusual power of survival and the ability to reach the very pinnacle of achievement at the age of 78.

Here was an extraordinarily person of mature belief, who recognised and attempted consistently to apply in all his written works, speeches and actions the values of objective and clear thought, and of the careful use of evidence, maintaining these as the outstanding and lasting qualities of what it meant to be human.

Yet it cannot be denied that he has sometimes shown prejudice and even irrationality, indicating something unresolved and hidden in his character; when checked and aware of how he has caused outrage he has carefully tried to adjust and adapt, even backtrack on it. Ninety per cent of the time he applied his thinking dispassionately to the problems of living faith, as well as the eschatology, of mankind, and much of what he said, and some of his Church reforms, have been apt and effective. But over them there has always been a shadow cast – that of the past.

Did he as a man, during his reign as pontiff and one of the most important figures on earth, stand as an example, not only for Catholics everywhere, and for adherents of other faiths – but also for the majority of secular and scientific non-believers in Western Europe, and the United States? This is one question I will attempt to answer.

† † †

For a long time Ratzinger was, as Prefect for the CDF, in the shadow of Pope John Paul II. He and the former Pope did not always see eye to eye – for instance he declined to endorse the Pope’s view of the Third Millennium as ‘a spring of the human spirit’. He opposed the 1986 World Day of Peace: ‘This cannot be the model,’ he commented. He said the restrictive side of his job was to help the Pope with the necessary “‘Nos” when the Pope [John Paul II] had a natural inclination to say “Yes”.’ This prompted the Pope to respond, ‘Maybe I should have been more assertive.’

When Ratzinger became Pope Benedict he remained ambiguous and mystifying, except in theological matters of faith, and never showed the world who he was until that turning point of his pontificate in 2010 when the sexual abuse crisis threatened to overwhelm the Church. Like his predecessor, he admitted to and underlined the fact that everyone has a good side and a bad side, but on the whole – except for occasional mishaps and unconscious, or unintended, lowering of his guard – the range and many-sidedness of his character never emerged in daylight.

He always refused requests for interviews, including my own, and he has only opened up to one journalist, after a tryout with John Paul’s Italian chronicler, Vittorrio Messori, namely his fellow Bavarian Peter Seewald, suggesting he had a need to control what emerged in his own words in the way of personal confession, keeping it very much to the minimum, while the exchange of more general views are almost on a fifty–fifty basis with his interrogator.

I take one word from him, his excellent and humble description of his Jesus of Nazareth – as a part guide to what I am attempting – a ‘proposal’ for looking into the inner man, who may be divided into three: Joseph; Ratzinger; and Pope Benedict.

Perhaps ultimately there was always some residual fear in him, which again makes it important to show or try to examine where it came from, and how it influenced him: ‘What is this need to see a person?’ wrote Pope Paul VI when he became pope. When evaluating a pope’s thought and influence just as a pastor and teacher it is perhaps not so important, but attempting a portrait of a figure on the world stage whose public utterances influence millions, and can cause both disasters and unexpected miracles, one cannot but look closely at the person.

Benedict pointed again to the contradiction in every human being in 2009 when he said in his book Paul of Tarsus that the inner contradiction of our being is not a theory. ‘As a consequence of this evil power in our souls, a murky river developed in history which poisons the geography of human history… Blaise Pascal, the great French thinker, spoke of a “second nature” which superimposes our original good nature’ – and Benedict concluded that ‘the power of evil in the human heart is an undeniable fact.’

This ‘second nature’ has, to a debateable degree, been evident in the Vatican during the 32 years that Ratzinger has been there, first as cardinal then as Pope Benedict. The question to be asked is: to what extent has he stopped the Vatican encroaching upon the power of the good, or encouraged the good that would check and dispel it? Given the recent scandals and disclosure of thefts, sexual impropriety, corruption, the tendency of the Vatican to operate like a royal court, with all the ensuing gossip, bitchery, vanity and secrecy that goes with it – it might be thought the overall spectacle (in spite of the many good men) has changed little since the time when Cardinal Newman described Rome: clear from the top of the hill – down below full of malaria and swamps. Will the river of faith in global consciousness, if not to many millions of devout followers who don’t want to notice it, always have a constant murky streak?

I am not going to presume to say what should be done by his successor, now that Benedict has so bravely stepped down. It is not for nothing Benedict has earned his title of ‘the Pope of Surprises’.

† † †

Those critical of Benedict have tended to overlook the fact that the man is primarily an intellectual visionary and idealist, and as such a great inspiration to the body of the Church as its teacher and mentor, rather than to the world outside. This visionary aspect of his character, as deep and many-layered as that of some of the great visionaries of mankind, has been ignored. It has flowered late in life.

Perhaps we should look to literature and art for similar late flowerings of vision, to the example of Sophocles, in Greek theatre, writing Oedipus Rex at a comparable age – not only a great play and the first example of detective fiction, but a seminal work for Freud and modern psychology – and leaving its sequel unfinished when he died at the age of ninety; or to Rome and the world of Italian Renaissance art, in which Michelangelo worked in his eighties designing St Peter’s Basilica.

Ratzinger’s own vision has been much quieter and more restrained than either of these – less a heaven ‘full of the sound of clashing swords’ in W.B. Yeats’s trenchant phrase, rather the muted harmonies of a pretty Bavarian landscape. It is expressed through the carefully chosen words and concepts of an intellectual. Some critics wrongly claim that this, strictly speaking, is not a vision at all, or if so, hardly realised; and it is too soon to assess how much, or the degree to which it holds together consistently, or will last as a positive influence.

Yet whether it came in written form, simplified in his many lucidly simple homilies and encyclicals, or through measures, less convincingly, attempted in governance of the Catholic Church, there was still an aspiration to transcendental scale and cosmic relevance. It is far too early to ask, ‘Was this the right vision for the Catholic Church?’ My intention is to show as far as I can how that vision came about, and what it did or did not reflect of the inner man.

† † †

No one can deny that largely, even with the new advances of globalisation, we live in an age of double standards and precarious peace. The disrepute into which the Catholic Church fell as a result of increasing public knowledge of abuse cases from 2010 onwards, which began and even were evident much earlier, reduced trust and prestige to their lowest ebb. Tens of thousands left the Church, numerically compensated by new members joining mainly through the increasing birth-rates in Africa and South America, so the Church could save face in the statistics but not cover the decline in morale, especially in Europe and North America.

First I have to return to that earlier period of his past when similar double standards in much more extreme operation were the rule rather than – as some apologists of the flagrant abuses and present dark trends maintain – a series of unrelated episodes and unhappy exceptions.

* From the root ‘Lethe’ meaning forgetting, as in the mythological river in Hades; aletheia, with its prefix a-, means ‘against’ or ‘not’ forgetting.

Prologue

Unlikely Bankroller

… Our natures do pursue

Like rats that ravine down their proper bane

A thirsty evil, and when we drink, we die.

William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, I, ii

Spring 1919. In the late-eighteenth century, neo-Roman nunciature or embassy of the Roman Catholic Church in Munich the stick-thin archbishop, the Vatican’s legate or nuncio, to all observers gentle and pious, knelt at prayer in the chapel.

Aged 43, six feet tall, with beautiful tapering hands, large and luminous dark eyes, the pallor of his skin had an eerie transparent effect, as if projecting from the inside a cold, white flame. A Roman by birth, from a family of Church lawyers, he had arrived in Munich two years earlier, and impressed the war-weary Bavarians with his vigorous efforts to organise relief.

But now the city was in turmoil. Law and order had broken down. Left-wing mobs were on the rampage in the fashionable districts. The rump Reichswehr, the regular force allowed by the Versailles peace treaty, stayed in their barracks. The 20,000 strong newly recruited Free Corps, a right-wing, paramilitary force of mainly demobbed soldiers, had not yet arrived on the scene, to restore order and carry out savage reprisal.

There was an unholy banging on the embassy door. On the steps outside stood a bloodthirsty, armed contingent of Red revolutionaries. They had already killed those who resisted, and had taken aristocrats from the racialist Aryan Thule Society as hostages.

Eugenio Pacelli, the papal ambassador, rose to his feet. He had a lavish domestic entourage, but no security guards. Sister Pasqualina Lehnert, a beautiful South German nun, accompanied him everywhere. Later to be known as La Popessa (the popess) when Pacelli became Pope Pius XII, the wartime pope, it was Pasqualina who opened up the door.

The revolutionaries stormed into the embassy. Some demanded car keys and straight away stole the official vehicle.

Pacelli stood his ground and confronted the invaders. Haughty and dignified, he spoke with calmness and courage, telling them they had broken diplomatic law. The leader stepped forward and pressed the barrel of a rifle against his chest. Pacelli reeled. He tottered on his feet. Pasquelina ran to his aid, shouting at the insurgents to leave him alone.

Ultimately the Communists left him unhurt, but he suffered a terrible collapse, the first of many nervous collapses. A later generation, when psychological terms became current, would call it a trauma, and say that what he had suffered from was post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. The invasion of his sanctuary and psyche by a Jewish-led Bolshevist mob produced a psychological wound from which he never fully recovered. It gave rise to bloodcurdling nightmares from which, it was alleged, he would awake screaming for the rest of his life.

† † †

Enter Kurt Eisner, a middle-class Jewish theatre critic from Munich’s bohemian Schwabing district. Short of stature, small, wire-rimmed spectacles perched on his nose, he sported a heavy grey beard, a black cloak, and huge broad-brimmed black felt hat in the style of Lenin. Eisner had brought mayhem to Munich the previous November, 1918. Released from Cell 70 in Stadelheim gaol after a sentence for organising strikes to end the war, Eisner sneered at political convention.

Eisner wasn’t exactly a Marxist but a way-out Democrat given to theatrical gestures. When immediate social breakdown and anarchy threatened the Social Democratic Party’s control of Munich he organised a brass band and banners, summoned a crowd, exhorted it to occupy the army barracks and seize the Bavarian State Parliament.

He met no resistance from the diminished defence force allowed by the Versailles treaty, and was endorsed both by the revolutionary ‘Workers’ and the ‘Soldiers’ Councils’. Then, as leader, calling himself an Independent Social Democrat, and supported by the Majority and Independent Social Democrats, he proclaimed the Bavarian kingdom a Republic, the ‘People’s State’.

All sides condemned Eisner as a pacifist agitator, a Jew, a journalist, a bohemian and, worst of all – as they were in Bavaria – a Berliner. He had, even more nefariously and treacherously, published the secret and incriminating documents, collected by Felix Feuenbach who was his secretary, blaming the Germans for starting the war. Food supplies dwindled because the Bavarian peasantry withheld their support. Eisner’s ‘government’ quickly foundered, while the Allied powers requisitioned the trains.

On 21 February 1919, Count Anton von Arco-Valley, an aristocrat and 19-year- old Munich student, shot Eisner twice at point-blank range in the street, killing him instantly. Murder and recrimination followed, with huge demonstrations at Eisner’s funeral. Munich sank more and more into unregulated mob rule.

While on paper there was a legitimate Bavarian government of Majority Social Democrats, it couldn’t command authority. The Workers and Soldiers’ Councils distributed arms, and then a Soviet-style putsch seemed in the offing. Writers such as the playwright Ernst Toller – ‘coffee house anarchists’ – proclaimed Munich University open to all applicants except those who would study history!

Armed clashes between the ‘Red Army’ and Social Democrats became frequent. More militant Communists squashed the airy-fairy idealists to proclaim a Bolshevik Bavaria. They contacted Lenin in Moscow. ‘Have you nationalised the banks yet?’ enquired Lenin politely (and astutely). They followed his advice, and took hostages from the aristocracy and middle class.

The ‘Goddess Reason’ reigned in Munich’s Catholic churches; radical priests of a persuasion that would later be termed ‘Liberation Theology’ joined the insurrection. Soon they were training a ‘Red Army’ of 20,000; many were boarded in churches and monasteries, where weapons were stored. It seemed Bavaria was about to spearhead the Bolshevisation of Europe.

Pacelli had, before his shocking experience, already visited a leading Bolshevik faction which had supported Eisner’s seizure of power and made their headquarters in the former Bavarian royal palace. He wrote to his Vatican superior, in order to keep the Pope in Rome informed, that what he found was ‘chaotic, the filth completely nauseating…’ Once the home of a king, it resounded ‘with screams, vile language, profanities… An army of employees was dashing to and fro, waving bits of paper, and in the midst of all this, a gang of young women, of dubious appearance, Jews like all the rest of them, hanging around in all the offices with provocative behaviour and suggestive smiles…’

This female gang’s boss was their leader, Levine’s, mistress, a young Russian woman, a Jew and a divorcee, while Levine, aged about 30 or 35, was also ‘Russian and a Jew, Pale, dirty, with vacant eyes, hoarse voice, vulgar, repulsive, with a face that is both intelligent and sly.’ In this and from other statements and actions Pacelli displayed a physical repulsion which reinforced an inherited anti-Judaism present in his heart and in his theological conditioning. It was to pave the way for his reluctance in the future to denounce – or even allow through his silence – the persecution of, and the atrocities committed against, Jewish people.

When he had recovered from his nervous collapse Pacelli quickly took a hand in helping to reassert full Catholic and legitimate democratic authority in the Bavarian capital.

† † †

There was an even stranger and darker sequel to the break-in at his embassy.

Some weeks later, unannounced, an unknown young man rang the embassy door bell and asked to see the papal legate. He had, he told the gatekeeper Pasqualina, a letter of introduction from no less a personage than General Erich Ludendorff, a hero of the Great War. He was admitted at once.

Pasqualina ushered the respectably dressed young man into Pacelli’s study, and stood outside to listen to what followed. He told Pacelli he was an Austrian by birth who had fought in a Bavarian regiment and been decorated for bravery. Recently he had served as a Bundingsoffizier, an instructor to combat dangerous ideas among the rank and file. And now he was forming a new party called the Deutsche Arbeiter Partei (German worker’s party), or DAP. They badly needed money.

Pasqualina heard him say (as she wrote in her 1959 autobiography, which was not allowed to be published until 1983) that he was a Catholic and his new party were determined to stop the spread of atheistic Communism. ‘Munich has been good to me, so has Germany,’ he told Pacelli. ‘I pray to Almighty God that this land remains a Holy Land, in the hands of our Lord, and free of Communism.’

While Pasqualina listened to the young man’s impassioned words, what she did not see in her listening post was the mesmeric effect of his deep blue eyes and hypnotic personality.

These, as a later supporter wrote, transfixed you and pierced right into your very soul. Another disciple, Julius Streicher, editor of the Munich Der Stürmer, said of his own first encounter with this charismatic figure: ‘I had never seen the man before. And there I sat, an unknown among unknowns. I saw this man shortly before midnight, after he had spoken for three hours, drenched in perspiration, radiant. My neighbour said he thought he saw a halo round his head, and I experienced something which transcended the commonplace.’

The spell he cast was spiritual, the power that of an evangelist. Pacelli, who was hardly in the first flush of youth, allegedly fell entirely under the spell too, and was to remain so for many years. As Adolf Hitler left, Pasqualina saw Pacelli hand over a considerable sum of Vatican money.

‘Go quell the devil’s works,’ Pacelli told him. ‘For the love of Almighty God!’

Was this the start of an emotional subservience, almost a co-dependency – or at least a compliant response – by the high-ranking Catholic cleric to the future dictator of Germany?

Why this should ever be so was a mystery. Although in the words of one of his cardinals when he was pope, Pacelli was ‘weak and rather timid. He was not born with the temper of a fighter,’ this was by no means the whole story.

It was to have catastrophic consequences for the Catholic Church in Germany and for the whole world.

PART ONE

THE BOY FROM BAVARIA

What is the story of mankind?

What are good and evil?

What awaits us at the end

of our earthly existence?

Benedict XVI

An undated photograph of the Ratzinger family; Maria, Georg, Maria mère, Joseph, Joseph père.

1

Shadowland or Fairyland?

‘Co-operators in the truth.’

Ratzinger’s motto when consecrated bishop

A plaque on the wall of number 11 Markltplatz, Marktl am Inn, near the Austrian border, where on the other side of the River Inn, just less than forty years earlier, Hitler had been born, marks the birthplace of Joseph Ratzinger on Easter Saturday, 16 April, 1927.

That he was baptised on Easter Sunday with fresh holy water blessed the night before, which gave the child special protection, sets a tone which permeates most accounts, including Ratzinger’s own, of the very Christian atmosphere of his birth and early years. ‘I love the beauty of our country, and I like walking. I am a Bavarian patriot; I particularly like Bavaria, our history, and of course our art. Music. That is a part of life I cannot imagine myself without.’

Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, exactly repeats the sentiments and hobbies of many Bavarians who enthuse about, and are very proud of, their homeland. For example, the 18-year-old Hans Frank, later the first Nazi Bavarian Minister of Justice, wrote in his diary on 6 April 1918, ‘We Bavarians, members of a genuine Germanic race, have been armed with a powerful sense of free will; only with the greatest reluctance and under duress do we tolerate this Prussian military dominance. It is this fact above all that constantly renews for us the symbol of the great, unbridgeable dividing line made by the mighty Main River, which separates South Germany from the North. To our way of thinking, the Prussian is a greater enemy than the Frenchman.’

‘We remain anchored in our own Bavarian spirit because it is our cultural identity,’ wrote Ratzinger in similar terms, in his memoir, Milestones. ‘Our experience during childhood and youth inform the lives of each one of us. These are the true riches which we draw on for the rest of our lives.’

The Pope’s Bavarian background has been highly and romantically idealised by both he himself and commentators on his life. The Italian writer Alessandra Borghese calls him ‘the happy produce [sic] of a land such as Bavaria: Catholic from the start, firm in her faith, serious in her ways, but also warm in her feelings, fond of good music and thus of harmony, and always giving such colourful expression to life.’

Borghese rejoices in the link between Bavaria and her native city, Rome: ‘happiness and openness, love of conviviality are shared qualities… Benedict is often told Munich is Italy,’ she asserts.

Joseph’s parents by chance (or ‘providence’) were named Joseph and Maria (Mary in German and Italian). His mother, a miller’s daughter, the eldest of eight who had a tough upbringing, worked as a hotel pastry cook in Munich, while his father, from a slightly higher social bracket, came from an old family of poor Lower Bavarian farmers.

Joseph senior served two years in the Royal Bavarian Army before training for the police during the First World War at Ingolstadt. We learn nothing about this. He and his son would often go hiking when he was ‘on extended sick leave’, when he would tell Joseph ‘stories of his early life’, although Joseph does not tell us in Milestones what these were. He worked as a constable, or inspector, or commissioner (he is referred to as all three).

Joseph’s parents met through an announcement in the press that he was looking for a wife. Forty-three-year-old Joseph, in March 1920 – calling himself ‘a low-level civil servant’, according to Bavarian State archives – placed an advertisement in a Catholic newspaper for a wife, a girl who knew how ‘to cook and also sews a bit’, and who shared his faith. Today he would presumably have had to go through a dating agency, or post his details on the Internet.

As a policemen with poor pay he added that he would not ‘be displeased if she had some money of her own’. At the age of over forty, advanced in those days, he then wrote to his superior officers requesting permission to marry.

It would seem from the first he was unable to support fully a wife and family, similar to many a policeman today. Maria, still unmarried at the age of 37, came forward.

This was four months after the first advert, when, with little or no success, he had upgraded his CV to ‘mid-ranking civil servant’. This is not mentioned in Milestones as an important milestone, but in the Bavarian State archive. She had no money of her own but she did work. They married on 9 November 1920.

Joseph senior was grey-haired with a moustache, not a handsome man but rather scraggly-looking, and tenacious; he was, Joseph said with hindsight, ‘very strict, perhaps too strict’. He thought differently from the way one was supposed to think, and with a ‘sovereign superiority’.

Maria, on the other hand, was from all accounts cheerful and good-natured. She sang hymns to the Virgin Mary while washing up, which incurred her husband’s disapproval. His parents had ‘two very different temperaments… a difference which made them complimentary’. Both valued thrift, honour, and led a life of frugality, which enabled Joseph senior to put money aside and save for a home for his retirement.

Up until that time when they owned a house they lived in local constabularies manned by Joseph senior – ‘above the shop’, as had happened with Margaret Thatcher, although in Ratzinger’s case, and as the father was an important local functionary, the ‘copshop’ was a grander if more decaying establishment.

† † †

Karol Wojtyla, Pope John Paul II, mentioned that his birth sign, Taurus, was indicative of his personality. Joseph’s birth sign was that of Aries, the Ram, representing in its symbolic aspect sacrifice. The popular trait of this star sign promises a gradual and deliberate rather than a spontaneous rise in life, but also a potential leadership complex, which has to be reined in. The combination of an Arien and Taurean, John Paul II, who later became Pope Ratzinger’s close colleague, made for an excellent match. At the same time, interpreters of the sign warn of a tendency to temperamental outbursts much to be avoided (or not shown).

Joseph’s uncle Georg, Joseph’s great-uncle, had been a priest and theologian, a Reichstag deputy and member of the Bavarian parliament. He championed the rights of peasants, and, noted for his richness of thought and animated exposition, and frequent changes of political allegiance, he had once written attacking the political economy of Adam Swift.

Georg was also fiercely anti-Semitic in his writings and thought, blaming Jewish financial power for undermining traditional German values of discipline, modesty, family integrity and the Christian faith. (This is not mentioned in Joseph’s memoir, Milestones, published in 1998, nor in Peter Seewald’s biography, Benedict XVI .)

‘Jews were part of the alien world of Munich rather than rural society,’ writes Nicholas Boyle. ‘Georg’s long and severe involvement with urban and economic affairs must have made him a somewhat suspect character… If Josef is said to have had “no friends as a boy” it must in part have been because he was repeatedly uprooted and learned to put his trust in no one but the family and the church.’

To have had an avowed intellectual anti-Semite in the family presumably, too, was not a bad credential for survival in the Nazi era, for if necessary, Nazi investigators dug deep into family history. Not that there was any need for or use made of this.

Cultivating an uncritical, detached picture of Joseph’s early life runs the risk of being accused of concealing other sides of the story by not bringing attention to them. Today’s world is curious and questioning. In 1996, as cardinal, he praised Georg’s work supporting peasant rights, and against child labour. ‘His achievements and his political standing also made everyone proud of him,’ Ratzinger told Seewald. But from what he tells us and what we know we can never properly form a picture of the father and the family, as we can do in the case of Karol Wojtyla. He tells us what he feels he ought to tell us, in view of his position, to form the correct idea of him that we should have.

Just before Joseph was two, his father was posted to Tittmoning, a small and picturesque baroque town that bordered Austria. Joseph had only just survived an attack of diphtheria, which made him unable to eat. They lived once more in the town square, in what was formerly the seat of the town provost. A proud house, Joseph recalled, ‘from my childhood land of dreams’, although the reality was more often than not that of his aged mother hauling up coal and wood two flights in a dilapidated dwelling with crumbling walls and peeling paint.

On 15 March 1929 Hitler launched an impassioned appeal for the German Army to think again about its rejection of National Socialism, and its support of the Weimar Republic. Even so, the Nazis still floundered – until the Germany economy suddenly collapsed.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 changed Hitler’s fortunes. Then, and only then, did Nazism seriously begin to catch fire in the hearts and minds of the German people.

In 1931 Cardinal Michael Faulhaber visited the town to confirm some children. According to legend, Joseph, who welcomed the cardinal with other children by singing songs, was so enamoured of the blood red of the cardinal’s cassock, and his black, chauffeur-driven Mercedes limousine that he shouted, ‘One day I will be a cardinal too!’

Georg, his elder brother, calmed him down by saying, ‘I thought you said you wanted to be a house painter.’ He had already expressed this desire – perhaps from consideration of the state of the Tittmoning house’s interior decoration.

The dwelling also housed a special holding cell for prisoners, who were fed from the frugal family table. On the other hand, Joseph senior’s uniform was not exactly short on ceremonial flourish. He wore, for formal parades, not only his green uniform, polished belt and buckle, sabre and revolver, but also the distinct and rather comical Bavarian policeman’s helmet.

Whenever the father went out on night patrols, Maria prayed with her children that their father would come home safely. During his day duty on the beat Maria used to man the telephone in the office. It was a very ordered, institutional life from which, in some form or other, the children were never to deviate in the future.

By the end of 1932 his father had been posted again, this time to the less idyllic village of Aschau, where the authorities rented for him and his family part of a pretty farm house a local farmer had built for himself. They lived in second-floor rooms and had running water but no bath. In front of the house stood a roadside cross, and in the garden there was a pond into which one day Joseph fell and almost drowned, leaving him with a lifelong fear of drowning.

The ground floor was occupied by the office and an auxiliary policeman, an ardent atheist and Nazi, who outside in the garden performed military exercises with his wife. This policeman attended Catholic Mass to spy on the priest and make notes on the sermon with a view to inform, in case it was seditious. To do this he had to genuflect before the Stations of the Cross, which caused some merriment in the family.

Joseph, who had attended kindergarten, began primary school in Aschau. He noticed how his father more frequently, as time went on, had to ‘intervene’ at public meetings in disturbances caused by the violence of the Nazis. As usual, he does not say what actually happened, and what form his father’s intervention took. When he became an altar boy, he witnessed the Nazis beat up his parish priest. Again, there was no resistance in the Ratzinger family.

It was during this time Jews began to leave, or were driven out of their homes and businesses. Or maybe it was the Communists who suffered. Erich Röhm’s Brown Shirts, the SA or Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment or Assault Division), were now a self-proclaimed, auxiliary police force.

We take Ratzinger’s word for it that from the start his family were conscientious objectors to Nazism, although there is no other proof of this than his word. But at heart, while unwilling to conform, they were quietists rather than active or clandestine opponents during the rise of Nazism, and later against the Reich.

On Sunday Joseph senior smoked a Virginia cigarette and read the anti-Nazi Gerade Weg. The parents never discussed the declining political situation, as they did not want, so Joseph later wrote, to involve the children. Yet to think of the many millions of children who were to perish later, as a result of the acquiescent attitude of many millions of Germans, is mind-boggling.

‘Man lives on the basis of his own experiences,’ said the Polish John Paul II, who was Ratzinger’s direct predecessor in the papacy. Joseph’s experience in childhood was that you didn’t discuss such matters. Joseph senior and Maria weren’t people who came forward to assert their views. They were Mr and Mrs Bavarian Everyman. They didn’t discuss politics, certainly not in front of the family. They questioned a bit, but not too much. Their religion gave them faith in modest circumstances and they took heart and found security in finding them similar to those of their saviour. Obedient to the Catholic catechism, they surrounded their family with an atmosphere of love and attention. The two boys were intellectually very able and academically very clever, so the daughter took on a subsidiary role as they did everything they could to further the boys’ education, trying to make sure nothing would get in their way.

This was the early stage, when and where the resistance was needed. As the Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller wrote in a poem which became world-famous:

When the Nazis came for the Communists

I was silent.

I wasn’t a Communist.

When the Nazis came for the Social Democrats

I was silent.

I wasn’t a Social Democrat.

When the Nazis came for the Trades Unionists

I was silent.

I wasn’t a Trade Unionist.

When the Nazis came for the Jews

I was silent.

I wasn’t a Jew.

When the Nazis came for me

There was no one left

To protest.

From early on in his life, the colouring of Joseph’s speech probably came from his mother’s South Tyrolese idiom, which ‘mixed with the dialect of Upper Bavaria and the accented colouration of the vowels, later became virtually his trademark’. The accent was provincial. The mindset of his early years, too, was markedly Bavarian, by which I mean baroque. This cultural influence over his thought and character went deep, but more important was the unconditional love of his parents and the refuge his family supplied.

With his Bavarian background, and first eighteen years spent in Nazi Germany, he shared a culture with Hans Frank which had a very different outcome, yet still exerted a deep influence over his thought and character.

The ‘true riches’ of his childhood and youth had a dark side, and it could possibly be that, in the future, sometimes in drawing on that past he lacked sufficient self- knowledge to be clear what exactly he was drawing on.

2

The Pied Piper of Lower Bavaria

Unfortunately, the narcissistic personality … formed in the earliest years is heavily endorsed by our society with its emphasis on imagining ourselves. The vast, technically empowered world of advertising stresses day and night the importance of being with the ‘right’ people, in the ‘right’ clothes, in the ‘right’ car, in the ‘right’ job etc. I must be forever improving my image, learning more and more to see myself in the image of the good life.

Sebastian Moore, Must I Tell You Who I Am?

Four years before Joseph was born, in 1923, when his older brother Georg was in early infancy, there happened in Bavarian history an extremely important event, which must have involved Joseph senior, as a Bavarian state policeman, in some way, possibly a very personal way – although we have no record of this. The momentous event took place in Munich, which was not very far away.

It would serve, even at this early time, to bolster up for the family and for the future Pope, the Catholic Church, both as a symbol and as a shelter and insulation from the traumatic experiences of their fellow Germans.

In the long term how strong and secure it would prove to be was another consideration.