Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spellmount

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

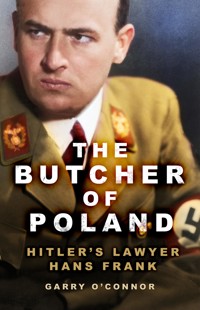

The life of Bavarian Hans Frank, one of the ten war criminals hanged at Nuremburg in 1946, has not received the full attention the world has given to other Nazi leaders. In many ways, he warrants it more. His life symbolised Germany's hubristic and visionary ambition to an alarming degree, much better than anyone else's, perhaps because he was an intellectual of the highest calibre. An early supporter of the Nazi Party, Frank ultimately became Hitler's personal lawyer and later served as Governor General of Poland during the Second World War. He was a fervent advocate of Nazi racist ideology and became the primary – if not the archetypal – symbol of evil, establishing a reign of terror against Polish civilians and becoming directly involved in the mass murder of Jews. The Butcher of Poland is a harrowing account of Hans Frank, the man who formalised the Nazi race laws.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Garry O’Connor:

Subdued Fires: An Intimate Portrait of Pope Benedict XVI

The 1st Household Cavalry 1943–44:In the Shadow of Monte Amaro

The Pursuit of Perfection: A Life of Maggie Teyte

Ralph Richardson: An Actor’s Life

Darlings of the Gods: One Year in the Lives ofLaurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh

Olivier: In Celebration (editor)

Sean O’Casey: A Life

William Shakespeare: A Life

Alec Guinness: Master of Disguise

The Secret Woman: A Life of Peggy Ashcroft

William Shakespeare: A Popular Life

Paul Scofield: The Biography

Alec Guinness, the Unknown: A Life

Universal Father: A Life of John Paul II

The Darlings of Downing Street: The Psychosexual Drama of Power

Cover illustration: Hans Frank, circa 1940. (brandstaetter / TopFoto)

First published 2013

This paperback edition published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Garry O’Connor, 2013, 2024

The right of Garry O’Connor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75249 862 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART ONE

1 Saving Germany from Self-Accusation

2 In the Superior Range

3 Gretchen

4 The Mission

5 Mephistopheles Unveiled

6 Sexuality

7 Bürgerbräu Cellar

8 Marriage

PART TWO

9 Mein Kampf

10 Bad Blood

11 Not Far from the Vienna Woods

12 Kirchenkampf

13 ‘A Humble Soldier’ and Il Duce

14 Faustus at the Feast

PART THREE

15 To Poland

16 Warsaw – ‘From Which Everything Harmful Flows’

17 Anni Mirabili of the Reich, 1940–41

18 Himmler Reacts

19 Redemption – The Real Gretchen

20 The Sex Life of King Stanislaus

21 L’Uomo Universale

22 Managerial Problems

23 The Prince Archbishop

24 Vogue La Galère

PART FOUR

25 Walpürgisnacht

26 To Nuremberg

27 The Butcher’s Conversion

28 Governor Faust Takes the Stand

29 Punishment

Appendix: Definition of the Term ‘Jew’ in the Government General

Notes

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Many have provided insights and ideas which have been helpful in the writing of The Butcher of Poland, or, as it was called before the final, uncompromising title, The Ultimate Doctor Faust, The Penitent of Nuremberg, and Poland is Nowhere, but especially I must thank Ian Hogg and Nigel Bryant for theirs. Thanks are due to Bill Traherne- Jones who read the book in draft, to Annette Fuhrmeister who also helped with the German, Julian Friedmann, Julia Reuter and Michael Holroyd, all who read the book in various drafts. I thank Claus Hant for meeting me and talking at length, and for the depth and fascination provided by the lengthy and revelatory notes to his novel Young Hitler.

Had I not stumbled upon Niklas Frank’s In The Shadow of the Reich, I wouldn’t have become involved with the subject, and I can’t emphasise enough what an extraordinary and inspirational memoir this is. I thank him very much for his contact with me over writing my book in its early stages, and the corrections and insights he gave me. Two other works I must mention which are crucial to understanding the Nazi mentality and German historical guilt are Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader and Gunter Grass’s Peeling the Onion. I would also like to thank all those at The History Press who have aided the production, especially my editor Shaun Barrington, who, as with the two previous books of mine The History Press have published in 2013, has been tirelessly enthusiastic and helpful.

To tell you the truth, they think whatever you want them to think. If they know you are still pro-Nazi, they say, ‘Isn’t it a shame the way our conquerors are taking revenge on our leaders! – Just wait!’ If they know you are disgusted with Nazism, the misery and destruction it brought to Germany, they say, ‘It serves those dirty pigs right! Death is too good for them!’ You see, Herr Doktor, I am afraid that twelve years of Hitlerism has destroyed the moral fibre of our people.

German lawyer at the Nuremberg Trials, 1945 in conversation with US Army psychiatrist, Dr Gustave Gilbert

I am absolutely convinced that Adolf Hitler was just a name representing the total worldwide collapse of ethics in the twentieth century. It began in 1914 with the First World War, when everyone killed everyone and there were no longer any moral standards. Revenge was the order of the day, every excuse justified.

Whitney Harris, leader of US prosecution team at the Nuremberg trials

Introduction

This is a cautionary tale that can never be told too often. Hans Frank’s colourful and sensational life has up to now only once been revealed in its vivid and dramatic colours – by his son, Niklas, in his book In the Shadow of the Reich (Der Vater, Munich, 1987; English version Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1991), with a different emphasis from what follows. Niklas Frank’s coruscating and shocking account, bravely honest and compelling in judgement, and entirely unforgiving, is an autobiographical stream of outrage, related in the first person by the son who was brought up in his father’s shadow and had to deal with what his father had done, and his reputation. This cry of rage was followed by two further books, both as yet untranslated into English: Meine Deutsche Mutter (My German Mother, Munich, 2007) and Bruder Norman! Mein Vater war ein Naziverbrecher, aber ich liebe ihn (Brother Norman: My father was a Nazi criminal, but I love him, Munich, 2013). The trilogy, in ‘discharging Niklas’ heavy burden’, has been described in the German press as ‘taboo-breaking, tragic and painful’.

Otherwise, apart from a factually meticulous and exhaustive life in German by Dieter Schenk, untranslated into English, and a primarily academic account of his legal career by Dr Martyn Housden, an English historian, Frank’s life has in the English-speaking world tended to be overlooked or overshadowed in the lurid and overpopulated gallery of Nazi criminals – swamped by the tens or hundreds of books written on his confrères in evil that even today continue to flood the market.

Frank’s life has for me one particular fascination: I believe no one has remarked on it except for the subject himself. In an extraordinary and rather eerie way it reflects the universal story of Faust. It was of course Hitler who, as Mephistopheles, was behind this weak Faustian central figure, and pulled his strings, first in Bavaria, then in Poland. So it is Hitler as much as Frank who shares the ghastly limelight as ‘The Butcher of Poland’.

It provides a new twist to, or development, of the Faust theme and legend, and it has many points of contact with Sophie’s Choice and Schindler’s List, although without the inspirational central figure of the latter. It would more than lend itself to be being filmed. The force of destiny, the good angel, the alleviating spirit which finally prevails in the face of unimaginable evil is Poland itself, and the Polish people. The story is unremittingly dark, yet hardly darker than Doctor Faustus, Marlowe’s great play. The raging doubts and weakness of Frank’s character, and the sacrifice of his soul to eternal damnation are seen to be constantly at play, and provide the dynamic of the drama.

I have come to this subject in a curious way. First, I have known three actor friends and subjects of biography who have had a connection with the Third Reich: two of these gave memorable film performances as Hitler. First, Alec Guinness enacted his crisis and torment in Hitler:The Last Ten Days, in 1973; the second, Derek Jacobi, was cast as the Führer in Inside the Third Reich, in 1982. Ian Hogg, the third, played Alois, Hitler’s father, in Hitler: The Rise of Evil, a Canadian production. All three had in common the fact that they contributed to a knowledge of what made Hitler tick, what his inner life consisted of, and how it was ever possible that he became the destroyer and supreme tyrant of the last century.

There is a more intimate or personal touch which, from a family point of view, brought me slightly closer to the subject. Maggie Teyte, the operatic soprano who was my great aunt, when her career was in its heyday in the 1930s, took part in a triumphant London Philharmonic tour of Germany with Sir Thomas Beecham, who at the time was her lover.

Hitler, who wooed all celebrities, especially musical celebrities, who could be seduced to his mission, told Beecham, ‘I should have liked so much to come to London to participate in the Coronation festivities (of George VI), but cannot risk putting the English to the inconvenience my visit might entail.’

Beecham’s subtle reply apparently left Hitler looking bewildered: ‘Not at all. There would be no inconvenience. In England we leave everyone to do as he likes.’

Maggie Teyte was also introduced to Hitler. She told me in the 1970s, ‘he was an awful little man and he smelt.’ She refused to sing for him. This reminded me of a story about C.J. Jung, whom the Führer tried to summon to analyse him: Jung refused to leave Switzerland to meet him and take part in his charade. Yet others, like the Mitford sisters, queued up to meet him and found him charming.

Hitler played a great part in the life of Hans Frank, spiritually and emotionally a greater part than anyone else. It stimulated Teyte’s imagination for, later, when she came to prepare a concert version of Gounod’s Faust, she said, ‘Hitler really started it all. I could just see him – reaching out, twisting, destroying. He was the real Mephistopheles. I always thought he should be the centre of the opera – not that milksop Marguérite or that weakling Faust.’ So for her, as for Frank, the Satanic or Mephistophelian figure in Germany was always Hitler.

It will hardly come as a surprise, then, that the main thematic influence on what follows is Thomas Mann’s great flawed masterpiece, Doctor Faustus, which I have read and drawn on in the Penguin Classics translation by H.T. Lowe-Porter. Mann sees the origin and roots of Nazism in the formation of character, personality and actions of its leader, as deeply embedded in German cultural history. To give one example, the following statement of the novel’s narrator, Serenus Zeitblom, is an indication of the main concern of Mann’s fictional investigation:

In a nation like ours, I set forth, the psychological is always the primary and actual motivation; the political action is of the second order of importance: reflex, expression, instrument. What the breakthrough to world power, to which fate summons us, means at bottom, is the breakthrough to the world – out of an isolation of which we are painfully conscious, and which no vigorous reticulation into world economy has been able to break down since the founding of the Reich. The bitter thing is that the practical manifestation is an outbreak of war, though its true interpretation is longing, a thirst for unification (Doctor Faustus, p. 297).

Thomas Mann might well have put his finger on the deep cultural roots of Nazism in Doctor Faustus. There is a further consideration, however, often neglected by those who write up the crimes of the Third Reich and their perpetrators and hold them wholly and solely responsible for what they did, which of course they were. This other factor, which it is wrong to overlook, is the dynastic importance of German families and German family life.

In Western culture the interrelation between gods or God, the spiritual aspect of life and the responsibility of man, especially in the working out and influence of the family on history as well as the personal fate of individuals, find repeated and profound expression in the deep-rooted family drama. These emerge in such seminal works as the Oresteia trilogy of Aeschylus, Sophocles’ Theban plays, which depict the life of Oedipus and his family, and then in the body of works by Shakespeare, Racine, Chekhov, Ibsen and, closer to our age, O’Neill, Miller and Tennessee Williams.

Likewise, in the drama of the Third Reich’s birth and rise to power, the importance of the families who were its progenitors has largely been overlooked, forgotten or deliberately whitewashed in the fear that so many of their components and features are common to the universal human family. For example, in the Canadian film, all the scenes depicting Hitler’s family life and in particular his crucial and influential relationship with his cruel father, were cut prior to being broadcast.

In Heinrich Himmler’s family, where three brothers, Gebhard, Ernst and Heinrich all joined the SS, the impeccable middle-class professional, teaching, religious, patriotic background of the family, stretching far back into the past, was a formative influence that was duplicated thousands if not millions of times in German families in 1900, the year both Heinrich Himmler and Hans Frank were born.

What is described in the following pages by its adherents and followers as a heroic epic, namely the two Hitler putsches – the earlier failure in 1923 and the ultimate seizure of power in 1933 – were great days for the mainly very young participants; to be compared, for example, to the formation of the Irish Free State, to the birth of Israel, or the emergence of an independent India after the turmoil of the Raj withdrawal, and the civil war in which hundreds of thousands died – and to the present-day events in the Middle East in which the same constituents seem all too prevalent. The fact they all led to very different ends is not the point I am trying to make here.

During the First World War German boys who were left at what was called ‘the home front’ saw war as ‘a game in which, according to certain mysterious rules, the numbers of prisoners taken, miles advanced, fortifications seized and ships sunk, played almost the same role as goals in football, and points in boxing’. A game that provided a whole generation of boys far more profound excitement and emotional satisfaction than anything peace could offer.

Here was one of the strongest roots from which the vision of Nazism grew. In fact, this underlying vision of Nazism experienced war, not by what happened and was experienced by soldiers of the front, but more crucially for the future, in the battle games of German schoolboys playing at home and school. It was, then, that generation born like Frank in 1900 and after, who became keen and ambitious in their early twenties, fuelled with the romantic heroism of boyhood and with the emotional and sexual drive of early manhood (and an unexpressed sexual and power drive seeking expression and fulfilment), which became the engine in the powerhouse of National Socialism.

But it was not only the younger generation. Fathers, mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers were all behind it, too. For instance, in June 1936, when Heinrich Himmler was made head of the German police in the Reich ministry of the interior, his parents and brothers, all of whom had received the highest possible educational grades and qualifications as upholders of German society had, according to Katrin Himmler (the daughter of Heinrich’s younger brother Ernst), no reservations about the all-powerful position of the SS and the police:

In their letters [to Heinrich] his parents express their admiration for the ‘magnificent black columns that are your creation’, as his father wrote on the occasion of the SS parade on 9 November in memory of the fallen ‘heroes’ of the Beer Hall Putsch. Heinrich had secured seats for them for both the 1934 and 1935 ceremonies. Gebhard and Ernst used meetings with Heinrich to put the case for further promotion within the SS. And they too, thanks to their brother, had the opportunity now and then to meet those who wielded power in the Reich (Katrin Himmler, The Himmler Brothers, p. 163).

They were not the exception but the rule. The collective general crime of almost all Germans of that time was that they not only lacked the courage to speak, as Primo Levi asserted, but they lacked the desire to do so. They embraced Hitler’s apparently invincible totalitarian regime.

Once established, ‘The pressures it can exercise over the individual are frightful. Its weapons are substantially three: direct propaganda or propaganda camouflaged as upbringing, instruction and popular culture; the barriers erected again pluralism and information – and terror …’ (Levi, The Drowned and the Saved, p. 35ff).

The Canadian film Hitler: The Rise of Evil, shown in Britain on Channel 4, in which Ian Hogg played Alois, Hitler’s father, was an attempt to bring a more balanced view of Hitler’s origins. It showed Alois bullying and beating his son. One scene had Adolf setting fire to his father’s beloved beehive out of revenge, and his subsequent brutal chastisement by Alois; during this, Klara, Adolf ’s mother, tries to intervene and in turn is hit. Another time, Alois humiliates Adolf in front of his work colleagues.

These scenes were either cut or reduced to a tiny glimpse as part of the producers’ or distributors’ urge not to portray Hitler as too human a figure, or, as he emerges in those early scenes, with his inability to make relationships and his obsession about sketching buildings, as a sufferer from autism. While never mentioned in the film, this is how the producers and actors thought of the young Adolf – as a withdrawn victim of paternal violence.

Before Derek Jacobi played Hitler, he had played Dietrich Hessling, a Teutonic louse, in the television series Man of Straw, adapted from the satirical novel written by Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann’s brother, which exposed to ridicule the pre-First World War German family. In Hessling’s slavish worship of the Kaiser, Mann mocks the habit of obedience, the unbending adherence to rigid family values, which gave rise to Nazism.

When he came to play Hitler, Jacobi’s take on the role was Hitler the actor, Hitler the performer, Hitler as written up in that multi-faceted portrait of him by Albert Speer, his Minister of Armaments. So here again was the revelation of a very different aspect of the dictator’s mind and actions.

Derek told me of an incident when filming on location in Munich. They had roped off a central platz where he had to make a speech. All the young children around wanted his autograph. Then, for a key speech, they employed a crowd of local students as extras. They stood there as he spoke and were told to react and applaud at the end. ‘I made the speech. I came to the end. They clapped. Silence. And then slowly they all raised their hands in the Nazi salute. I shuddered. It was so inbred. A reflex …’

The most expanded character study of the dictator was that of Alec Guinness in Hitler: The Last Ten Days. Guinness spent many months getting inside the evil character, so many that his behaviour upset his wife and friends – but he said this didn’t depress him so much as obsess him.

He showed Hitler first and foremost as the artist manqué, which of course he was, who sacrificed his vocation to save and rebuild his country. Guinness’ Hitler had a sense of humour, he was an anti-bourgeois misfit, and a puritan. So Guinness explored this inner life, and it is an irony that this puritan, anti-smoking tyrant was beaten by leaders who were all heavy smokers and not noted for temperance.

The film was banned in Israel for showing Hitler in too human a light, which is perhaps another irony. It was also heavily reduced on the cutting room floor in order not to provoke too much empathy for the man, and to conform to the reigning demonisation. It thus never made the impact the director and star hoped.

In the authoritative endnotes to his novel Young Hitler, the contemporary German writer Claus Hant provides convincing evidence that Alois was a petulant know-all and miser, a brutal, choleric type with few friends who often, when coming home drunk at night, would beat his wife or young son with a hippopotamus hide whip similar to the one Adolf carried setting out as a party leader. According to Hitler’s sister Paula he got a beating every night. Only when his father died in 1903, when Adolf was 14, did relative peace come to the family.

Four years later his mother Klara was operated on for breast cancer. Contemporary witnesses, as cited by Hant, confirm that Adolf was particularly self-sacrificing in taking care of his mother:

When she died later that same year, three days before Christmas, the young Hitler was overcome with profound anguish. The Jewish physician Doctor Bloch, who treated Hitler’s mother until her death, recalled later in exile in America that ‘he had never in his career seen anyone as filled with grief as Adolph Hitler’. Karl Krause, his butler, recalled in his memoir: ‘he had a photo of his mother on his night-stand, it was on his writing desk, in the library, and in the study.’

Significantly, indicating his vulnerability over any exposure of what happened in his family past, as well as his own unresolved and repressed or suppressed feelings over it (as well as changing his family name from Schicklgruber to Hitler), Hitler eliminated all traces of his past. To erase the truth, not just the details of his parentage, he even went to the point of murder, and the demolition of town and building. He hardly spoke of his father beyond the briefest of mentions.

Joachim Fest, a biographer of the Führer, concluded that ‘to veil and transfigure his true person was one of the main endeavours of his life. Few other figures in history have stylised themselves so forcibly and concealed their true selves with such seemingly pedantic consistency’ (Young Hitler, p. 345, note 102).

Finally, I should mention that I have taken a liberty in two sections, where the sources are so many, the citations themselves hearsay, speculative dialogue or verbatim report, to use this dialogue, add to it, and knead the narrative into what is known as ‘faction’. My precedent for this is the practice of Peter Ackroyd in his monumental Charles Dickens. Elsewhere Ackroyd has made the claim, with which I heartily concur, that ‘Biography is convenient fiction’.

PART ONE

1

Saving Germany from Self-Accusation

‘The Russians,’ said Deutschlin sententiously, ‘have profundity but no form. And in the West they have form but no profundity. Only we Germans have both.’

Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus

President Woodrow Wilson, a good Presbyterian, put forward plans to reform the United States by taking business out of the hands of businessmen, and turning it over to the politicians. Now, in 1918, with the brief of changing the wider world after World War One, to make Europe a safer and saner place to live, he had selected a cohort of distinguished American scholars, men like himself, an ex-President of Princeton, who derived their ideas from books, to eradicate evil forever from the conduct of governments. He had the whole civilised world for his classroom. ‘Open covenants of peace openly arrived at’ stood at the heart of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points to which the Germans had agreed as the basis for the Armistice on 11 November 1918.

At Versailles, in May the following year, the Germans found themselves not so much an active participant in peace negotiations, as passive recipients of what became known as the diktat of Versailles imposed on them. Wilson, dressed in black, lean in figure and face, eyes magnified by shiny lenses, presided. Président Clemenceau of France, aged 78, a diabetic with grey silk gloves hiding his eczema, made it clear revenge would be his agenda: ‘The hour has struck for the weighty settlement of our accounts.’ But while in the West it had lost, Germany had been winning the war in the East and still had an army of 9 million men under arms. Count von Brockdorff-Rantzau, Germany’s negotiator to whom Clemenceau addressed these words, did not deign to rise from his seat to read a bitter reply. Wilson’s response to this strengthened the perception of his growing anti-German animus: ‘What abominable manners! … It will set the whole world against them.’ So much for peace.

The Diktat, signed finally on 28 June 1919 by the German Social Democrat Government yielding to overwhelming force, described by Robert Lancing, Wilson’s Secretary of State, as Germany ‘being forced to sign their own death warrant’, provoked fury not only in Germany. Maynard Keynes, British Treasury representative at the Paris Peace Conference, resigned. He thought the economic reparations forced on Germany by the ‘Damned Treaty’ were a formula for economic disaster and future war. In a letter to a friend he called Wilson ‘the greatest fraud on earth’; to Lloyd George, British Prime Minister, he wrote, ‘I am slipping away from this scene of nightmare.’

Keynes returned to his alma mater, King’s College, Cambridge. Here, he penned a blistering condemnation of the Conference, as much to re-enlist himself, it seemed, with his cultural peers in the Bloomsbury set – they disapproved of his Realpolitik engagement. His The Economic Consequences of Peace reverberated with coruscating force around the world. It was written to warn how the effects of imposing a ‘Carthaginian peace’ on Germany would contribute directly, as the French historian Etienne Mantoux said later, to the future war Keynes sought above all to avert.

For all his academic aestheticism, his attachment to the pacifist sensitivities of his Bloomsbury peers and sponsorship of the arts, especially the theatre, Keynes was an economist. He knew, as Thomas Mann said, ‘the economic is simply the historical character of this time, and honour and dignity do not help the state one bit, if it does not of itself have a grasp of the economic situation and know how to direct it.’

Like the subject of this book, Keynes was a man of two worlds. Not so that master progenitor of twentieth-century evil who, in August 1914, aged 25, had fallen on his knees at the outbreak of war and thanked God. This was the moment he termed, in high-sounding phrases, of ‘unity and integrity’, the moment that National Socialism was begotten, when Germany was freed from a world of stagnation which could go on no longer, an appeal to duty and manhood, an opportunity for heroism. But above all, it was a means of achieving a life in which state and culture could become one. This book is about Hans Frank; but without some consideration of Hitler, we cannot know Frank, so I hope the reader will forgive what may seem like digressions both here and in what follows, but, it is hoped, will not prove to be so.

Adolf Schicklgruber, although born on 20 April 1889 in Braunau am Inn just over the Bavarian border in Austria, was bursting with the consciousness that his adopted land was to become the dominating world power. He was convinced the twentieth century would be Germany’s century: that after Spain, France and England in previous eras, it was Germany’s turn to lead the world. War would be the means, an understanding of power combined with a readiness for sacrifice.

Defeat and Hitler’s wartime experiences drove home that earlier flash of subjective truth. His dangerous role in the war was that of a volunteer dispatch runner; he was an infantryman but was close to officers in command who were ready to use men as cannon fodder. He had already lived the life of a down-and-out in Vienna from 1908 to 1912 before he moved to Munich. On the very edge of society, scratching a living by whatever means he could, he had written or worked on plays and novels and even a musical drama in the style of Wagner. He painted pictures which he tried to sell and while the general misconception is that he gained his political insights from newspapers and magazines, in time he became more famed for burning books than reading them. The truth is that he was obsessed with books and read voraciously. His roommate in Munich, Rudolf Hausler, complained he read until three or four many mornings. Not only did he have a photographic memory, but the range of his reading was immense, from the Divine Comedy, Goethe’s Faust and William Tell, to Carl May’s Wild West stories for boys. Much later, Hans Frank recalled that Hitler claimed to have had works by Homer and Arthur Schopenhauer with him in the First World War trenches. Ernst Hanfstaengl, at one time close to the Führer before becoming an opponent, stated that ‘Hitler was neither uneducated nor socially awkward … My library came to experience his voracious appetite for books.’

At the front Hitler had found himself engaged in fighting ‘man-to-man’ and overcome the instinctual aversion to killing, confirming his social-Darwinian worldview that life was a continual savage battle. Combat was for him a great formative event. The community of comradeship, in the absence of homeland and family, grew to be overwhelming. The Bavarian or ‘List’ Regiment comprised 3,600 men when first deployed. Four years later, by the time of the armistice in November 1918, 3,754 of the troops that had served in the regiment had been killed. So few of his comrades survived that it is not surprising Hitler came in time to believe Providence was on his side. Wounded twice, he received six medals and decorations, including the exceptional Iron Cross 1st Class, usually only won by officers. But he was not officer material in the opinion of his military superiors, despite this bravery, and never rose above corporal. Complimented later on this promotion, Hitler admonished his superior Max Amann: ‘I would ask you not to do that, I have more authority without stripes than with stripes.’ It enabled him later to separate himself from the career officers who were seen as the architects of German defeat. It would become commonplace to state that at heart and soul, together with all his ex-servicemen followers, he never stopped being a soldier. Some psychologists have claimed the traumatic but positively experienced war motivated him subconsciously and that this created a ‘repetition compulsion’ that stayed with him.

After being blinded by gas at the front line at Werwick in October 1918, Hitler was taken to the Bavarian Field Hospital stationed near Brussels to be treated. Then, exceptionally, he was separated from his fellow wounded and sent 1,000km to a small hospital in Pasewalk, near the Polish border, which specialised in treating ‘war neurotics’. The authorities were determined to separate these from other serving men lest they spread the infection of hysterical or psychotic behaviour to other men and affected morale.

No documentation exists of how or with what he was treated, though various testimonies were collected by the US Secret Service which confirmed that what Hitler called his ‘blindness’ caused by the gas poisoning had an unadmitted, psychopathological dimension. It was undoubtedly at Pasewalk that Hitler experienced a transformation – whatever the effect of the assumed mustard gas, both physical and psychological – from an unexceptional introverted ‘armchair scholar’ and practical joker, lax in attitude and with eccentric ideas, into a visionary with a burning mission. It was there, hearing of the unrest and armed uprising in Munich, that he became seized with certainty, in the form of supernatural, ecstatic visions, of a victorious Germany, in the course of which his eyesight was restored. Such delusion, reported the Frankfurter Zeitung on 27 January 1923, ‘eliminates any complexity, and that alone makes a huge impression in the spineless times we live in. These people are certainly not lacking in activity, but rather in the sense and value of the goals by which their will is achieved – which is why they are so dangerous in their obsession to the nation as a whole.’

Before this transfiguration Hitler had believed himself to be a genius; now he ‘knew it’. Before, he had believed divine Providence protected him; now he was utterly convinced. Likewise, his convictions became ‘absolute truths’. It was this transformation, this unshakable certainty in his own power, which gave him unlimited authority and empowered him to represent his views with an unparalleled fanaticism.

Not surprisingly, then, he kept quiet about what had happened to him in Pasewalk, only given a mention in Mein Kampf, never refeering to it as ‘paranormal’ again for political reasons, nor that he had been diagnosed as a war neurotic. This became another secret for, as he often said, ‘a secret known by two people is no longer a secret.’

He left Pasewalk Hospital on 11 November 1918. The news of the German Army’s surrender brought on the sickening sense, as he later described it in Mein Kampf, of selling out, of a stab in the back that gave him both a personal and national sense of utter collapse. The total despair served only to bolster his visionary or hallucinatory summons to free Germany from bondage.

It was a conversion as powerful as any in religious history, a spiritual shock and re-orientation of such enormous proportions it transformed Hitler’s whole personality. Unlike Nietzsche, he never believed God was dead. God was alive and well and infused him with power, took him away from his early failure and depression, and gave him a feeling he was the new Godhead. Hysterical blindness and autism may also have contributed to his certainty that Providence had chosen him to perform the mission of liberation. He was, from now on, to be guided ‘with the certainty of a sleepwalker along the path laid out for me by Providence’. His sight, so he claimed, came back the next day.

It was the prohibition, the disbanding of the German Army, which spurred him into action in 1919. He had to recreate that moment in 1914 when Germany had been conscious of its military power; when she united in it, and exulted in it. Had not the Treaty of Versailles robbed Germany of its decisive character, denied the activities that were its very life-blood, Hitler would never have come to power. ‘The exercises, the receiving and passing on of orders, became something which [Germans] had to procure for themselves at all costs,’ wrote Elias Canetti, the Nobel Prize-winning author:

The prohibition on universal military service was the birth of National Socialism … The party came to the rescue of the army, and the party had no limits set to its recruitment from within the nation. Every single German – man, woman, or child, soldier or civilian – could become a National Socialist. He was probably even more anxious to become one if he had not been a soldier before, because, by doing so, he achieved participation in activities hitherto denied him.

So, for Hitler, the prohibition of the army by the Diktat of Versailles became the prohibition of the specific and sacrosanct practices he could not imagine life without. Every man’s sacred duty became the re-establishment of this faith of his fathers. Hitler could whip up resentment and a desire for revenge against the world, could rally support for his vision, by repeating and repeating the slogan Diktat of Versailles with unwavering monotony. The paranoiac could probe the nation’s wound and keep it bleeding, proclaiming the phrase at mass meetings with terrifying and coercive force.

So he joined up again as soon as he could, enrolling in the remnant German Army as a press officer and propagandist in what was now a politically motivated force. From now on, from that moment of rebirth or conversion, Hitler was to act with a kind of genius. He was able to make things happen exactly as he had foreseen and wanted them to happen. Here was a satanically inspired Mephistopheles who, in the future and among his legion of servile subordinates, would find many fanatic followers, and one young Faust in particular, close to his mind and will, ready to sell his soul for lavish reward.

2

In the Superior Range

Hans Michael Frank, Nazi Germany’s top lawyer, was born eleven years after Hitler in Karlsrühe, Bavaria, on 23 May 1900. He was christened a Catholic and, as he said himself, adhered to the liberal doctrine of being ‘an Old Catholic’. This meant he belonged to a breakaway body of the Munich Church which, led by the famous theologian Ignaz Döllinger, didn’t adhere to the nineteenth century edict of papal infallibility, and was in some ways akin to the Anglican Protestant Church.

On the face of it, his childhood was not all that extraordinary. He had a younger sister, Elizabeth, and a brother, Karl junior, nine years older. Magdalena, his mother, was an independent-minded, sensual, irrepressible woman of old Bavarian stock, but neither particularly intelligent nor spirited. The daughter of a small food shop owner in Munich, she was obliged to work and did not attend any schools. She married the much older Karl Frank to find a better life, but was bored after some years.

Karl senior was an outwardly respectable middle-class lawyer originally from the Rhineland; according to his grandson Niklas, he was ‘a very uninspired mediocre character and a bad lawyer because he was not very bright’. A photograph of him with Hans aged 12 shows a bald man in his fifties, wide and bushy browed, sporting a walrus moustache. He is formally dressed, and has his hand on Karl junior’s thigh. Hans has dark hair parted on the left and is wearing a brass-buttoned sailor suit. In another photo we see a younger Hans in Bavarian top hat with boots and knotted scout tie, his doll-sized sister in headscarf and rural waistcoat and skirt, standing next to him. A solid, ordinary middle-class Bavarian boy, one might think – in appearance at least.

All was not as it seemed on the surface. Magdalena, increasingly bored, fled the marital home and set up house in Prague with her lover, a teacher, not really an intellectual but more a dealer in foodstuffs and coal. Elizabeth and Karl Junior joined her there. Judging by the accounts we have of Hans’ early years, his mother was around him perhaps to the age of 10. He was a quiet lad, of an obstinate frame of mind. He preferred studying to frivolous games with other boys. Magdalena was especially proud that, on his first day at school, he took a newspaper with him and could already read it.

By the age of 10, Hans had moved in with his father running a law practice in Munich, and there he went to the famous Staatliche Maximiliansgymnasium attended by many eminent Germans, including the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Werner Heisenberg and future pope Joseph Ratzinger. Hans excelled at everything; he was an all-rounder, although apparently keen on outward form and display more than inward commitment. As one of his school friends described it, he accumulated information in order to show off.

He lived with his father in a second-floor flat in Munich’s Barerstrasse, where they kept chickens which sometimes ran free. The desertion by his mother must have told heavily on him, judging by what he was to say later: ‘The mark of the man is to be unconditionally the master. Weak men are worse than women, for when they are weak they are cripples.’ Presumably he referred to his father, who had been unable to hold on to his mother in the family home. The absence of this feisty woman would seem to have made him a lonely, introverted boy, studious and quick to engage with and embrace a higher purpose in life, as well as devote himself to dedicated and intense study – with the caveat given above, that such learning was for display more than for intellectual nourishment.

He formed some homoerotic friendships at school, none of them lasting. He passed through fairly usual phases, first with a platonic attachment to an older art and music teacher known as Ernst Sp., a ‘free spirit’ who encouraged him to breed tropical fish, and started to give him ‘thirsty glances’ before the First World War separated them. At school one playground companion was Karl Sch., the same age, believed to be homosexual. They went hiking together in the countryside around Munich. ‘He played an important role in my life,’ said Hans; they wrote each other letters with amusing wording and thought they were clever.

The father’s presence exacerbated the brooding resentment of the son, who each lunchtime would meet his father in the pub near his office in Schelling Strasse. We are unsure at this stage whether Karl senior had already been disbarred a first time for embezzlement, but we do know it happened later. There is a description of him as a freelance lawyer working from this public house on Schelling Strasse. For cash-in-hand he would write letters, advise and even take on cases on a very ad hoc basis. He seems to have had friends who helped him find briefs. In 1945, in his prison cell at Nuremberg, Hans spotted a newspaper report that Dr Jacoby, ‘a Jewish lawyer in Munich, who was one of my father’s best friends, had been exterminated at Auschwitz’. One thing is certain: Karl was a deceitful, crooked lawyer, whose conduct instilled or provoked in his son a strong need to profess rectitude and honour, although this tended rather to fluctuate. How relative this would become to circumstances and opportunity will in time grow clear.

It seemed Karl senior gave Hans, without the latter knowing it, early master-classes in corruption. The old man had, so his grandson Niklas wrote, ‘a way of getting experienced women into the sack: somehow or other he would sweet-talk them into it with his clever chit-chat about being a lawyer, at the same time he was taking off his skivvies.’ The Creszentia Breitschaft affair happened later, when Hans was on the threshold of fame; but it was indicative of the whole process of the Frank modus operandi. As Niklas said, ‘Anyone who got involved with the Frank family was caught like a fly in a Venus flytrap.’

The way ‘Zenzi’, as she was known in the family, fell victim to the swindling lawyer is a grotesque farce that could have been written by Bertolt Brecht, another Bavarian, born in Augsburg two years before Hans. An unscrupulous ‘procuress’, Fran Elise Lutze, used to steer unmarried or widowed women of some means between 40 and 50 towards the dapper legal rogue. Zenzi owned a railway-station restaurant in Lentkirchen, and she fell for Frank senior. They began an affair, and Frank set financial terms on marriage: meantime, as the liaison went on Frank took money from Zenzi with the promise he would marry her if she paid for his divorce from Magdalena, Hans’ mother. Not only had she to pay 1,200RM, but also a regular 50RM a month. And this was not all he extorted from her. By this time, having joined in the deception too, Hans got his father’s mistress to loan him 500 marks to help him move house. Even though he was by now a Reichstag deputy, Hans also asked for more:

My dear Frau Breitschaft, I ask you for a great favour. Constituents of mine in Silesia have suffered enormously in consequence of the ban on the publication of two newspapers, the Schlesischer Beobachter and the Schlesische Tageszeitung. I, too, have suffered serious personal loss. Would you help out just one more time? You know, of course, that you are my only creditor, and also that all banks are closed to us. Grant me a final one-year loan of 1,200 reichsmarks. I shall then pay it all back in regular monthly instalments. You would be doing us a huge service. The battle is difficult, but Germany must be free! Can you send the money – 1,200 reichsmarks – directly to my address at the Reichstag, Berlin? This will be the last time.

Father and son milked the poor woman for all they could. Karl senior found another mistress, a Fräulein Donauer. Ultimately, after he and his son conspired together to steer themselves through the dreck (mud), Zenzi, reduced to physical and verbal threats and then bankruptcy and joblessness, won a token law case against them.

This was but one of the family skeletons serving to harden Hans’ relatively young heart. There were more. Yet alongside this dark, early material of personal corruption, the idealist, infused with the same biological mysticism of Germany’s future leader, had long been sketching paths of his own future glory.

Just before his eighteenth birthday, Hans began to keep a diary in which his sense of race, of nationhood, loomed ominously large. On 6 April 1918 he wrote:

Today I mustered in as a recruit [in the army], one of the generation born in 1900. Having been declared fit for active service in the infantry, I was assigned to the imperial regiment. Today, for the first time in my life, I learned from personal experience how crude the executive mind of the Prussian military system really is, that compulsive outgrowth of pedantic discipline in the spirit of Frederick the Great. We Bavarians, members of a genuine Germanic race, have been armed with a powerful sense of free will; only with the greatest reluctance and under duress do we tolerate this Prussian military dominance. It is this fact above all that constantly renews for us the symbol of the great, unbridgeable dividing line made by the mighty Main River, which separates South Germany from the North. To our way of thinking, the Prussian is a greater enemy than the Frenchman.

His regiment was the 1st Bavarian König Infantry, stationed at Marsfeldt Barracks, and he was about to experience war for the first time. But Hans already seemed to lead a charmed life. Germany laid down its arms and he started classes again at the Maximiliansgymnasium. Perhaps it was the schuld (guilt, but the German word has a double meaning, viz debt) of his personal family circumstances, as much as the Kaiser’s defeat, that inclined him to idealism and purity – and to hold forth in airy rodomontade:

People of Germany, return to your roots, as long as there is still time. Preserve your ideals. With all your might, pull yourselves up out of this swamp of speculation and materialism that threatens to seduce and engulf you. Return to Nature, return to your own soil. Only there will the healing process you so badly need come to fruition.

He was not quite eighteen. Into this frothy outpouring a note of bitterness has already crept. He wrote of ‘A nauseating and unfortunately typical scene in a café. A Frenchman – surrounded by flirtatious German females entertaining him with their foolish giggling. Is that not a derision of our people, our nation? Unconscionable!’

In fact, a combustible contrast to idealism – the cumulative repression of feelings of hatred (towards his father, possibly also towards the mother he loved but who had not found a way to stay with his father), towards the victors of the war, and envy – were already building up in Hans. Ressentiment, resentment, a concept defined by Friedrich Nietzsche, had been the obsession of Max Scheler, the Munich-born philosopher, who had, even before the Great War, defined it as a universal, negative condition of man, both in its personal and historical contexts. In the Bavarian capital city, ressentiment was set to become a dominating feature.

His undoubted sharpness of mind notwithstanding – he had an IQ of 130 or more, ‘in the very superior range of intellectual abilities’ – manifest at the age of 18, Hans showed these feelings of nothingness, the release from which was soon to dominate several powerful, disaffected political movements. While Scheler believed in the unique significance of human emotions, especially love, and the importance of heroic or saintly models for the development of the moral life, Frank, like a small but significant minority of Germans, was increasingly caught up in a widespread moral and ethical vacuum and seeking other mentors. He found himself questioning the existence of God and decided that the Almighty, who most decidedly had shown himself not to be on the side of the Germans, had some important questions to answer: ‘How futile is the question, whether there is a God, since after all there is a soul, which leads us, a flame from the everlasting fire. But can anyone answer the question, where is this God?’

In the context of Germany in late 1918 to early 1919, this questioning young German wanted and was looking for a heroic model; instead of God, he found Napoleon:

Once again the story of Napoleon’s life, which I am reading now for the third time, touches me profoundly. Whence comes this compelling urge in me to pattern my life after this man’s? It must be truly glorious to rise in dizzying flight to such heavenly heights, no matter how great the fall that must follow … The desire to experience these heights burns like a fire within me. But my path shall go, not like that of Napoleon, over the bodies of those cursing and seeking to destroy him, but instead past the milestones on the way to the liberation of humanity. A united and free World Reich will then be the ultimate creation of the Germans.

On 19 December 1918 he writes (temporarily reinstating the Almighty): ‘Lord God, send us now the man who will bring us order … I wish for our nation men who can once again restore it to universally acknowledged prominence, while keeping it firmly anchored within. We must succeed in this!’

He was by no means pessimistic: on 2 January 1919 he writes, ‘With shining eyes I look to the future.’ Then he backpedals – maybe, he thinks after all, he is up to it: ‘Our nation today is incapable of leading a state able to flourish. Shall I be the one to lead the revolt of the slaves?’

Hans was not an exception in the Germany of his day. In many ways he was the intelligent German norm. Heinrich Himmler’s background was even more normal and not subject to the vicissitudes of Frank’s family life. He and his two brothers, all talented scholars, had the most sheltered but at the same time stimulating early years. Their parents took care to ensure their sons, who had the best gymnasium educations on offer in Munich, ‘were suitably prepared for their future professional and social positions, and this demanded not only an all-round education in the humanities, which was chiefly their father’s responsibility, but also the secondary virtues that were so highly valued in those days’.

Heinrich was a meticulous recorder of all details of life, a fervid family correspondent, and attentive to all aspects of social respectability. As his grand-niece records:

The ties between Heinrich and his family, which remained stable and unbroken, are misrepresented both in historical and biographical research as well as in the family folklore – perhaps because they all wanted to keep their distance from such a criminal character as Heinrich Himmler, to see him as a ‘one-off ’, as someone abnormal that they and their normal environment had nothing to do with.

But Heinrich had no overpowering belief in himself, for all his skill in organisation; he was denied robust good health, and never thought of himself as a supreme leader: he sought a Messiah.

Not so Hans Frank, who entertained much more grandiose ideas. Was he destined to become the German Napoleon? Was he to be the one to lead – or was it to be another?

3

Gretchen

A woman is loved by a proper man in three ways. As a dear child that one has to scold and perhaps punish in its irrationality, that one protects and cares for because it is delicate and weak and because one loves it so much. Then as a wife and as a faithful understanding comrade who fights her way through life at one’s side, ever loyal and without hampering the man’s spirit and putting him in shackles. And as a wife whose feet one kisses and who, through her feminine softness and childlike, pure sanctity, gives one the strength not to weaken in the hardest struggles, and grants one at ideal moments of the soul the most divine bliss.

Heinrich Himmler

There was for Hans Frank, even in the Napoleonic mind-set he favoured, a redeeming angel. He had met, and fallen in love – to the intense, romantic degree of which he was capable – with a fellow student. But she wasn’t a Josephine. The chrysalis Doctor Faustus had found his Gretchen: Lilli Gau, if that was her name. Later we learn her married name, which was Wertel. We imagine her, tall, slender, blonde-haired, with blue-black eyes, a lovely line of lips, a soft maidenly bosom. In fact, later descriptions confirm she was tall and beautiful. Cupid’s dart struck into the heart of 18-year-old Hans.