Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

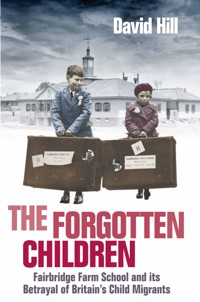

In 1959 David Hill's mother - a poor single parent living in Sussex - reluctantly decided to send her sons to Fairbridge Farm School in Australia where, she was led to believe, they would have a good education and a better life. David was lucky - his mother was able to follow him out to Australia - but for most children, the reality was shockingly different. From 1938 to 1974 thousands of parents were persuaded to sign over legal guardianship of their children to Fairbridge to solve the problem of child poverty in Britain while populating the colony. Now many of those children have decided to speak out. Physical and sexual abuse was not uncommon. Loneliness was rife. Food was often inedible. The standard of education was appalling. Here, for the first time, is the story of the lives of the Fairbridge children, from the bizarre luxury of the voyage out to Australia to the harsh reality of the first days there; from the crushing daily routine to stolen moments of freedom and the struggle that defined life after leaving the school. This remarkable book is both a tribute to the children who were betrayed by an ideal that went terribly awry and a fascinating account of an extraordinary episode in British history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Map of Fairbridge Farm School Village

Preface to this Edition

Preface to Original Edition

Book 1

1. Journey Out

2. Origins

3. A Day in the Life

4. Settling in

5. Families

Book 2

6. The Boss

7. Child Labour

8. Suffer the Little Children

9. Retards

10. The Children’s World

11. Leaving Fairbridge

Book 3

12. Against the Tide

13. Legacy

Notes

Bibliography and Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

Illustrations

Copyright

For Stergitsa and Damian

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The first party of Fairbridge children bound for Molong from Britain in February 1938.

The Fairbridge Farm School, built in an arc around Nuffield Hall.

‘Boys to be farmers.’ A trainee boy harrowing.

‘Girls for farmers’ wives.’ Christina Murray (right) making butter outside the principal’s house above Nuffield Hall.

‘This is not charity, this is an imperial investment.’ The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, in 1934. He launched a fund-raising appeal in London for Fairbridge with a personal donation of £1000. (Photograph courtesy of APL)

Kingsley Fairbridge, the founder of the farm schools. He believed, ‘The average London street Arab and workhouse child can be turned into an upright and productive citizen of our overseas Empire.’

Princess Elizabeth after her marriage, 1947. She donated £2000 from her wedding gifts ‘to assist individual old Fairbridgian boys and girls get a start in life’. The loan fund failed. (Photograph courtesy of Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/APL)

Lord Slim became chairman of the London Fairbridge Society. Slim dismissed Principal Woods when he proposed to remarry a divorcee, but took no action against staff who physically abused the children. (Photograph courtesy of Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis/APL)

David’s party of 1959 in front of the magnificent John Howard Mitchell House in Kent prior to leaving for Australia. Back row, left to right: Mary O’Brien, John Ponting, Richard Hill, Paddy O’Brien, Dudley Hill, Billy King, David Hill. Front row: Myrtle O’Brien, unknown, Wendy and Paul Harris, Beryl Daglish, unknown.

Eight-year-old Ian ‘Smiley’ Bayliff in his new outfit, shortly before sailing with his three brothers to Australia. His parents tried unsuccessfully for years to get their boys back from Fairbridge.

Vivian Bingham arrived at Fairbridge as a four-year-old and was treated badly by her cottage mother, who held her head down the toilet for wetting her bed.

The magnificent first-class lounge of the S.S. Strathaird. None of us had ever seen the luxury we experienced on the journey out to Australia. (Photograph courtesy of the State Library of Victoria)

Once at Fairbridge we ate our meals from metal Illuss and bowls, sitting on wooden benches in front of lino-top tables.

‘The boss’, Principal Woods, a towering influence over Fairbridge for twenty-eight years, with his former missionary wife, Ruth, on the steps of the Fairbridge chapel.

A ‘widow of Empire’, cottage mother Mrs Hodgkinson, who had been Lady Routledge in India. ‘She was imperious, superior, upper class. We were there to do her bidding; slaves and lackeys on tap,’ recalls former Fairbridgian Michael Walker.

Five days on a train across the Rocky Mountains: Fairbridge children who came the long way round via Canada in 1940. A shy six-year-old Peter Bennett is on the left, obscured.

Gwen Miller as a fifteen-year-old trainee girl. She remembers Fairbridge as a ‘cold, heartless place’ where childhoods were stolen and the word love was never mentioned.

Ten-year-old Lennie Magee (right) at the dairy to pick up and deliver milk.

A report on Fairbridge noted that the beds had no pillows and ‘consist of wire mesh, which tends to sag, on a steel frame, with very poor mattresses. There is no other furniture in the dormitories and the floors are bare wood’.

Lunch in Nuffield Hall, with the boss silhouetted on the stage at the head of the staff dining table.

The trainee girls were inspected each morning before work on the verandah of Nuffield Hall by the Fairbridge hospital nursing sister.

The village bell ruled our lives. A kitchen trainee rings the breakfast bell.

On the steps of Nuffield Hall with the local vicar after the Sunday morning church service: the one occasion when everyone wore shoes.

Boys chopping wood.

The moment of the kill. Blood splatters as a trainee cuts a sheep’s throat at the Fairbridge slaughterhouse.

Bringing eggs down to the village from the poultry.

The dairy was the boys’ toughest job, involving milking at 3 a.m. and again at 3 p.m., seven days a week.

Tony ‘Fishy’ Bates and Bob ‘Blob’ Wilson baking the village bread.

Old mutton: preparing lunch in the village kitchens.

Garden supervisor Kurt Boelter, a former German tank commander, working with a trainee boy.

Most of the Fairbridge boys loved the boy scouts and the chance to go camping in the bush.

Waiting to see the village nurse on the back verandah of the Fairbridge village hospital.

Some cherished free time on a Wednesday afternoon: boys from Blue Cottage and neighbouring Canary Cottage play marbles.

John Brookman spent thirty years trying to find his mother. When he finally tracked her down he discovered she had died the year before.

Malcolm ‘Flossy’ Field (second row, second from right). One of the few Fairbridge children who did not come from a deprived background. He migrated to Australia twice in the same year.

Sports afternoon. Some boys played rugby league in bare feet.

A junior Orange High School rugby league team of 1960. David Hill is in the back row, third from the right. His twin brother, Richard, is the first on the left in the back row.

The former World War II Fairbridge Farm School bus, which became a famous sight around the west of the state for several decades.

Fairbridge children cut each other’s hair.

Tuesday afternoon’s cottage gardening. The annual cottage gardening competition was fiercely fought out among the longest-serving cottage mothers.

Fairbridge children were officially described as ‘generally educationally retarded’ and most were forced to leave school at the minimum legal age.

The Governor-General of Australia, the Duke of Gloucester and the Duchess of Gloucester on a visit to Fairbridge in 1946. The Duke became the president of the London Fairbridge Society when he returned to England.

Plan of the Fairbridge Farm School Village

PREFACE TO THIS EDITION

The publication of the book The Forgotten Children caused quite a stir in both Britain and Australia, where some of the revelations from hitherto secret files and from the stories of former Fairbridge children attracted widespread media coverage.

The Fairbridge Farm School Scheme was roundly applauded during the 70 years it sent impoverished British children to farm schools in Australia, Canada and Rhodesia. Fairbridge aimed to create worthy citizens for the British Empire by converting boys and girls from English city slums into farmers and farmers’ wives, and promised opportunities and an education that the children could not hope for if they stayed in England.

But for many of the child migrants, some as young as four years old and never to see their parents again, the story was very different. Many were denied the promise of a better future, and most were forced to leave school at 15 with no education to work full-time on the farm. The typical child experienced social isolation and emotional privation and spent his or her entire childhood without ever experiencing the love of a parent. When the young migrants left Fairbridge at seventeen years of age, they had nowhere to go and no one to go to. The Fairbridge files in both the UK and Australia that have never been made public show that Fairbridge failed in many of its aims and corroborate most of the experiences the former Fairbridge children relate in the book.

Since the book was released, more former Fairbridge children have come forward wanting to tell their stories. These include the allegation that Lord Slim sexually molested a number of the boys while visiting Fairbridge when he was the governor-general of Australia. Slim was a greatly respected and revered war hero, both in Australia and in Britain, who later became the chairman of the Fairbridge Society in the 1960s when he returned to live in England.

When I was researching the book, one of the former Fairbridge boys had told me that the then Sir William Slim had molested him and a number of others in the back of the governor-general’s chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. While I believed his story, the boy did not want the allegation recorded and was not prepared to publicly defend the claim, so I thought it was unfair at the time to include it in the book.

However, since then other boys have told newspapers in Britain and Australia that it also happened to them, including Robert Stephens, who happened to be at the Molong Fairbridge Farm School when I was there.

Robert says that he and a number of other boys of eleven and twelve years old were offered rides in the Rolls-Royce up and down the drive along the Amaroo Road between Fairbridge and the main road about one kilometre away. During the ride he was forced to sit on Slim’s knee as Slim slid his hand up inside Stephens’s shorts.

Other boys spoke of fondling in the back of cars as he toured the farm. How do you explain it? We were innocent kids. I guess we were vulnerable and in a position where no one could really speak out. No adult would believe these things happened, so you didn’t talk about it. You think you are the only one. Like so many things that happened at Fairbridge, they don’t go away. They live with you all your life.

Ron Simpson is now 78 years old and lives in Sydney. He came out to Australia and to Fairbridge in 1938 as a nine-year-old with his seven-year-old sister Mary and is another who now wants to tell what happened to him.

Ron recounts how his back was broken when he was beaten with a hockey stick because he was late getting in the cows for the early-morning milking when working as a trainee boy on the Fairbridge dairy:

It wasn’t even my fault. The cottage mother forgot to pull out the pin, so the alarm clock didn’t go off. The other boys woke me up, and there was a mad rush to get to the dairy and bring the cows in to milk. So we were very late and got down to breakfast at seven-twenty. Principal Woods came over and told me to see him after breakfast.

When I arrived at the principal’s house, I knocked on the door, and he said come in, and I had just stepped in, and he was there holding a hockey stick in his hand. He grabbed me by my shirt collar, pushed my shoulder down, then gave me a tremendous wallop across my lower back. I fell into a big black bath opposite the hallway, screaming in pain. He pulled me out of the bath, then he did the same again. This time I flew through the entrance door and hit every step on the way out.

Ron went back to work with constant and worsening back pain. A month or two later he was chopping wood for the village kitchen stoves when he collapsed and had to be carried in a wheelbarrow by another boy to the village hospital.

I was chopping wood, and as I stooped down to put it into the barrow I felt a terrible shooting pain from my lower back down my legs. I collapsed onto the ground and couldn’t move the lower part of my body. I felt no pain, but try as I might I could not stand. Another boy who was with me lifted me into the wood barrow and ran me down to the farm nurse. She put me into a bed and called for the doctor at Molong, who came and checked me out and said I’d be all right in a couple of days. The nurse treated my back with some liniment, and . . . they got me out of bed in three days, and I was in pain, and I couldn’t sit on my backside. I was sitting on my spine.

Back at work his condition worsened, and the pain continued until one day the local Molong vicar, who was visiting Fairbridge, noticed him crying in pain and unable to sit properly. The vicar asked to be able to take him to Orange Base Hospital. After some months he was transferred from there on a stretcher by train to Sydney Hospital.

Ron still has some of his old hospital records. For more than a year he lay in the hospital bed with sandbags supporting his back, and apart from being visited by Charlie Brown, a former Fairbridge boy who had joined the army, Ron doesn’t recall ever seeing his sister or any other Fairbridge children while he was there. Ron says he told anyone who asked how the injury had occurred, but no one followed it up with any further inquiry.

Eventually, when he was able to walk again, he was returned to Fairbridge and spent the next few years wearing a metal-framed brace around his torso that he only took off at night when he went to bed. After he left Fairbridge, he was found a job on a neighbouring property, and he remembers Fairbridge providing him with a new brace when the old one wore out.

More than 30 years later and after decades of back pain Ron received a message from another Old Fairbridgian that Woods, who was in retirement, was asking after him.

Tommy Cook, an Old Fairbridgian down at Dapto, saw Woods. Woods kept on asking for me and said, ‘If you see Ron Simpson, tell him to please come and see me.’ But I never did. I wouldn’t go and see him . . . Even just before he died, he asked to see me, but I wouldn’t go near the man. I didn’t go to his funeral either . . . I think he just felt guilty about what happened to me.

I just couldn’t go through and say, ‘It’s all right, mate.’ It’s been with me all these years, and it’s a dreadful thing to happen to anyone, to children.

Many of the children spent their entire childhood at Fairbridge with no one to turn to and feeling that no one cared anyway. But there were some good staff at Fairbridge who genuinely cared for the kids and who are still fondly remembered.

Following the publication of the book a man came forward to say that his mother had worked for Fairbridge in England and had for many years remained upset about what she saw.

We all knew her as Matron Guyler who ran the big Fairbridge house in Knockholt in Kent where we were all sent prior to being put on the ship to Australia. We all remember her filling our heads with exciting dreams of what Australia and Fairbridge would be like.

What we didn’t know is that she had never seen the place until she went to Australia on a visit in 1961 prior to her retirement. Apparently she was horrified with what she saw and protested, in vain, to the Fairbridge Society in England when she returned.

Her son Mike, who now lives in Australia, described his mother’s reaction to the visit in an email he sent to me after the book’s first publication:

My mother was horrified by what she saw at Molong, but really she only saw the surface. What she did see were cold, hungry, unhappy children. All the new clothes that they had when they left England were gone. The cottage was dirty and the cottage mother . . . defensive. The thing that most affected my mother was the look in one of the children’s eyes. I don’t know if it was a boy or a girl, but my mother told me that she never saw such a pleading look, and it went straight to her heart.

Michael was not a Fairbridge boy himself but he has been in touch with a number of Old Fairbridgians in recent years. He said his mother was now 98 years old ‘but still talks of her horror at what Fairbridge allowed to happen in Australia’. He said she was living in a nursing home near Epsom in England and asked if one of the former Fairbridge kids might be able to visit her to reassure her that it wasn’t her fault.

I wonder if there is any Fairbridge boy or girl who now lives near Epsom who might be able to visit her and tell her that she was not to blame. I know that she still feels betrayed by what she discovered. (She really has no idea of the full extent of what went on.) Her mind is still pretty good, and I think it would comfort her. Of course I am aware that there are many Fairbridge children for whom there is no comfort, and it troubles me that I have known many of the children who were subsequently beaten, starved, abused and denied love.

The Fairbridge organisations in both Britain and Australia still deny any failings of the Fairbridge scheme, as they did when giving evidence before parliamentary inquiries into child migration in both countries in 1998 and 2002.

A former Fairbridge girl, Claire B, now living back in England, said the book had prompted her to ask for her records from the UK Fairbridge office, where she was told The Forgotten Children ‘was full of tales and lies told by small children’. In Sydney the Fairbridge Foundation said it still wanted proof of what went wrong at Molong, even though much of the evidence came from the files that remain in its Sydney office.

Some locals from the Molong district and even some former Fairbridge children were upset by the media coverage and reviews that followed the release of the book, and a number have been critical of what they perceived as the negative picture the book painted of Fairbridge. The strongest criticisms have come from those who are so upset or disgusted by the book that they have publicly declared their refusal to read it. The chairman of the Old Fair-bridgians’ Association, John Harris, who was interviewed for the book, said he was ‘annoyed’ by the publication. ‘It will be everyone’s own decision whether they purchase the book, and in my case it will not happen,’ he said.

For many of the former Fairbridge children the recounting of their stories is the first time they have told anyone about their experiences. They have revealed in the book what they have been unable to tell even their loved ones and their families. I feared that some would be traumatised when they read about themselves for the first time, particularly about being sexually abused. However, most have said they have now been able to draw strength from reading that many other children at Fairbridge went through similar experiences.

And many of the families of the former Fairbridge children have said how they have found the book useful in understanding their parents. Many former child migrants never talk about what happened to them, which has left their families with little knowledge or understanding of their parents. ‘Thank you,’ said one woman. ‘I’ve never really liked my father, but now I can see why he is like that. I had no idea how much he suffered as a child.’ Now a number of former Fairbridge children have joined together and through the Australian law firm Slater & Gordon are taking action against Fairbridge. Most say that they are motivated not so much by the money but by a desire to see that the wrongs that were done to the children are at last acknowledged.

Following the original publication of this book in Australia a number of former Fairbridge children began a legal class action for the abuse they suffered during their childhood at Fairbridge. The defendants in the legal action included the Fairbridge Foundation, the Australian Government (which was our legal guardian at the time) and the New South Wales Government, whose Department of Child Welfare was responsible for the protection of the children.

The case was bogged down with legal technicalities by the defendants for seven years in the Supreme Court until 2015, when nearly two hundred former Fairbridge children were finally awarded damages of $24 million – the largest ever pay-out of its kind in Australia.

Gratifying though it was, no amount of money can ever compensate for a devastated childhood. The sad reality is that many of the children who spent their entire childhood in an abusive environment have never recovered from the experience.

PREFACE TO ORIGINAL EDITION

In 1959, when I was twelve years old, I became a child migrant. With two of my brothers I sailed from England to Australia, to the Fairbridge Farm School outside the country town of Molong, 300 kilometres west of Sydney. My mum, who later followed us out to Australia, sent us because she believed we would be given an education and better opportunities in Australia than she could provide as a struggling single parent in England.

Britain is the only country in history to have exported its children. Fairbridge was one of a number of British child-migrant schemes that operated for over a hundred years from the late nineteenth century, and altogether these schemes dispatched about 100,000 underprivileged children – unaccompanied by their parents – to the British colonies, mainly to Canada, Australia and Rhodesia. About 10,000 went to Australia. By the mid-1950s twenty-six child-migrant centres were operating in the six states of the country. About 1000 children were sent to the Molong Fairbridge Farm School, which opened in 1938 and closed in 1974.

The child-migrant schemes were motivated by a desire to ‘rescue’ children from the destitution, poverty and moral danger they were exposed to as part of the lower orders of British society. By exporting them to the colonies, it was thought they might become more useful citizens of the Empire. Contrary to popular belief, barely any of the children sent out under these schemes were orphans.

In an age before the state took responsibility for the welfare of poor children, the child-migrant schemes were operated by the Protestant and Catholic churches, and a number of children’s charities, including Dr Barnardo’s. Some of the schemes, including the Fairbridge Farm Schools, were created and operated by people from the upper classes. Such emigration programs enabled Britain to deal with its large population of poor children without addressing the massive social inequality that had created widespread poverty in the first place.

The Fairbridge Farm School Scheme was based on a simple proposition first presented by Kingsley Fairbridge in a pamphlet published in 1908, titled ‘Two Problems and a Solution’. The two problems were, first, how to open up the lands of the Empire’s colonies with ‘white stock’ and, second, what to do to with the large and growing problem of child poverty. The solution was to put them together.

Fairbridge promised that children who were sent to Australia would get a better education and more opportunities than they would in their deprived environments in Britain. His vision was simple: for boys from the slums of the cities to become farmers and girls to become farmers’ wives.

Children were sent to Fairbridge on the condition that their parents or custodians signed over guardianship to the Australian Government, which then effectively delegated responsibility for the children to Fairbridge until they were twenty-one years old. Fairbridge felt it had rescued these children from failed or irresponsible parents, so they did not want children reuniting with their families. They deliberately targeted parents who were unlikely to want to get their children back. But many parents did not fully understand what was involved when they signed away their custodianship, and those who did wish to be reunited with their children found it practically impossible.

By the late 1950s the traditional source of poor British children was declining and Fairbridge was forced to introduce the One Parent Scheme, whereby children were sent unaccompanied to Australia but their single parent followed them out later, found a job, established a home and was eventually brought back together with their children. This was the scheme under which we emigrated.

None of our family knew at the time that Fairbridge had been forced to radically change its rules and introduce this scheme in response to increasing opposition from the British Government and child-welfare professionals. The postwar years in Britain had seen some dramatic improvements in child welfare: the passing of the Children Act in 1948 heralded a more enlightened era, and child migration and large children’s institutions such as Fairbridge were falling out of favour.

Nor did we know that fewer than three years before, the British Government had secretly placed the farm school at Molong on a black list of institutions condemned as unfit for children. Fairbridge was able to mobilise its considerable influence in the upper echelons of the British political system to have the ban lifted, and children continued to sail.

Those of us who went to Fairbridge under the One Parent Scheme were far more fortunate than the Fairbridge children who were already there, and our experience was not typical of the majority of children. We were older when we arrived – my twin brother, Richard, and I were nearly thirteen years old, and our brother Dudley was fourteen. We would each spend fewer than three years at Fairbridge and, most importantly, our mother would follow us out, so we would eventually reunite as a family.

In contrast, children unaccompanied by their parents typically arrived at Fairbridge aged eight or nine years old. Some were as young as four. They would spend their entire childhood and youth at Fairbridge, where they would attend the local school till the minimum school-leaving age, then work on the farm for two years until they turned seventeen. The boys were then usually found work as farm labourers on remote sheep stations; the girls as domestic servants on farms. Many of these children would never see their parents after leaving England, and would spend their childhood suffering emotional privation and social isolation.

Few of the Fairbridge children were provided with the education they had been promised before leaving the UK and half would leave school before completing their second year of secondary school. Many left school without having acquired basic literacy skills and would struggle through life unable to properly read or write.

I had not planned to write a book about Fairbridge. In 2005 I completed a Diploma of Classical Archaeology at Sydney University, as I have for a long time been interested in the archaeology of the prehistoric to classical periods of an area in the eastern Peloponnese in Greece. I have also been involved for many years in the campaign to have the British return to Athens the marble sculptures taken by Lord Elgin from the Parthenon in the early nineteenth century.

Armed with my newly acquired archaeological qualifications, I thought I would first test my skills by conducting a heritage survey of the Fairbridge Farm School settlement at Molong. The old village, which had been home to some 200 people, mainly children, had become almost a ghost town. Having received barely any maintenance, many of the buildings had fallen into disrepair. A number of the cottages the children had lived in had been sold off and moved to other towns to become country homes.

With several other people, I formed the Fairbridge Heritage Association and we set about compiling the historic record of the settlement. The New South Wales Migration Heritage Centre and, later, the New South Wales Heritage office backed the Fairbridge Heritage Project and asked that we also record the oral histories of some of the children who had passed through the farm school.

I conducted about forty audiotaped interviews over the first three months of 2006, travelling to meet former Fairbridge children who lived throughout New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and southern Queensland. In March 2006, at the biennial reunion of Old Fair-bridgians at Molong, I arranged for three camera crews to film interviews that we plan to use in a TV documentary.

During the interviewing process I realised that while a lot has been written and said about Fairbridge, the stories of the children who lived there have never been told – and the picture their stories paint is very different and much more disturbing than the records of academics and historians. It was then that I decided to write a book about Fairbridge from the point of view of those who lived there.

I found myself both disturbed and angry about some of the revelations of former Fairbridge children, many of whom were speaking up for the first time. I wondered why seventy-five-year-old women would talk on the record of regular sexual abuse at Fairbridge when they had never discussed it with their husbands, children or grandchildren. Nearly every woman and most of the men openly talked about physical or sexual abuse. When asked why they were now prepared to tell of their experiences, some said they had never previously had the opportunity to set the record straight. Others said they did not have the strength or courage to speak out before, but now, as they were reaching middle age, found it easier to confront the ghosts of their past. A number who initially had declined to be interviewed heard that others had spoken and then came forward to say they now wanted to tell their story.

There are many others for whom it is still too difficult. One former Fairbridge girl, Susan, who was at the farm school when I was there and whose brother was in my cottage and later committed suicide, phoned to say she wanted the book to be written and wanted to tell her story but that it was still ‘too painful to open those doors that took me years to close’.

In another case, the wife of a man who was at Fairbridge when I was there wrote to explain why her husband would not be telling his story:

There are too many hurtful memories there. He arrived when he was barely seven years old. He really can’t remember any good things to say. He often talks about going to bed in the dormitory alone at seven years old, with the lights out and no one else there; scrubbing floors every afternoon from this age and only having a couple of hours off a week; working in the dairy at 3 am in the cold frosty mornings with no shoes on. Public thrashings, etc. This sort of discipline and loveless routine sets a person up for an untrusting and confused life.

Another former Fairbridge boy, Allan, whom I remembered as an interesting and colourful character, rang and asked me not to send any more letters asking for an interview. ‘I’ve forgotten a lot of it. I don’t want to remember,’ he said. ‘I’m happy now I have my eleven grandchildren around me. Please don’t write to me again – it’s too upsetting.’ I told him I wouldn’t bother him again and asked when his life had turned around. ‘It hasn’t,’ he said. ‘It never turned around.’

Almost all those I interviewed insisted their stories were ordinary and unlikely to be of interest to anyone. Yet every single one is special – even more so because nearly all of them experienced deprivation and disadvantage, and were denied the nurturing, love and support afforded to most other children.

Much of this book is based on my own experiences and the stories of others who spent part or all of their childhood at the Fairbridge Farm School at Molong. I was also able to access rather limited personal files about myself from the Fairbridge Foundation offices in Sydney and the London Fairbridge Society archives, which are now held at Liverpool University in the UK. A number of other Fairbridge children who accessed their personal files from Sydney and Liverpool have kindly made them available to me.

I have been given notes, letters, diaries, photographs, unpublished autobiographies and assorted other material by former Molong Fairbridge children in Australia, New Zealand and England. Altogether, I have used material from over one hundred people who were at Fairbridge from the day it opened in March 1938 till it closed in January 1974.

In addition to the children’s stories, I accessed material from the Fairbridge Foundation in Sydney, the Fairbridge Society archives in the UK, British and Australian parliamentary and government files, the National Library in Canberra and the State Library of New South Wales. I also accessed Department of Education and Department of Child Welfare files from the State Records office of New South Wales.

However, I encountered a number of difficulties when trying to access or use material from the Fairbridge organisations in Australia and the UK.

The Fairbridge Foundation in Sydney is the successor body to Fairbridge Farm Schools of New South Wales, which was responsible for running the Fairbridge school at Molong. When the foundation sold off the Molong site in 1974, it invested the proceeds. It donates the profits and dividends from the investments to other children’s charities. The Fairbridge Foundation supported the Fairbridge Heritage Project and contributed $10,000 toward the recording of the history of the Fairbridge settlement and the hiring of film crews for the interviews of former Fairbridge children.

The foundation is the custodian of the old Fairbridge Farm School files, which are kept in its Sydney office in a number of un-catalogued boxes. The records, which include farm production reports, principals’ reports, staff pay sheets and a limited amount of correspondence, are far from comprehensive. While the foundation allowed me to access the material in some of the boxes, it did not allow me to access the minutes of the Fairbridge Society Council meetings, which are also stored in its office in Sydney. This was despite the chairman of the foundation, John Kennedy, telling an Australian Senate inquiry in 2001 that the files would be made available to ‘bone fide scholars and researchers’.

I wrote to Kennedy in July 2006 asking that the foundation reconsider their decision to deny me access to the minutes. Four months later he told me the board had considered my request and decided that I could have limited access to the minutes, but I would not be allowed to use material that identified any child or staff member who had been at Fairbridge. I said that I already had extensive testimony and evidence from other sources that identified improper and illegal acts by a number of staff members.

In July 2006 I was able to gain access to the London Fairbridge Society files, which are in the Liverpool University archives and include the minutes of meetings of the Fairbridge Society. (I did not seek access to the individual files of Fairbridge children.) Before I was allowed to see the material, I was asked to agree to a number of restrictions that the UK Fairbridge Society had imposed. I had to sign a declaration that ‘I will not in any way by any form of communication reveal to any person or persons nominal information or individual details which might tend to identify individuals or their descendants.’ The rules stipulate that I cannot identify any Fairbridge child for one hundred years and any Fairbridge staff member by name for seventy-five years from the date of the lodgement of the files. I was obliged to ‘agree to abide by the decision of the director’ as to what might identify individuals. In the event, I did not need to use any confidential information from these archives to identify individuals as the names of children and staff set out in this book come from either my own knowledge, from information given to me by those I interviewed, or from a variety of other sources.

While I was in the UK researching at the Liverpool University archives, I was contacted by the chairman of the UK Fairbridge Society, Gil Woods, who had been tipped off about my research by the university and wanted to talk to me about the project. He explained that while Fairbridge no longer operated a child migration scheme it was still active in child welfare in the UK.

I told him that I had come across material in the Liverpool University archives that corroborated some of the more disturbing oral histories and asked that Fairbridge allow me to use this material in the book. Woods agreed to consider my request but said he was concerned that any adverse publicity about Fairbridge would make its ongoing public fundraising more difficult. ‘My highest priority is to protect the reputation and name of Fairbridge,’ he warned.

I found the papers of Professor Geoffrey Sherington of Sydney University very helpful. Sherington co-authored an excellent book titled Fairbridge, Empire and Child Migration with Chris Jeffery and also helped me access his papers (other than personal files), which are lodged with the State Library of New South Wales.

Finally, there are the records from the Department of Education and the Department of Child Welfare in State Records NSW in western Sydney. There are restrictions that prevent the naming of individuals in Child Welfare Department files. While some child-welfare records confirmed the maltreatment of children, it appears investigations by the department were rare as the children had no way of initiating any inquiry. The Education Department has a simple thirty-year restriction, which made their files more accessible. However, I could not find any records that shed light on the reasons why Fairbridge children failed to receive the same standard of schooling as other Australian children in the state school system.

Most of the information about Fairbridge in these files has never been made public. In many cases it reflects very badly on Fairbridge.

It has always been accepted that the Fairbridge Farm School Scheme, as with all the child-migrant schemes, was well-intentioned and that the Fairbridge organisation could not have been expected to be aware of the dreadful experiences of some children.

However, the hitherto secret files confirm that the Fairbridge hierarchy, and the British and Australian authorities, knew about many of the flaws and failures of the scheme, and the maltreatment of children, for decades. They reveal that Fairbridge consistently rejected criticism and resisted reform, even when changes would have improved the welfare of the children in its care.

Most importantly, the files confirm much that’s contained in the former Fairbridge children’s accounts, which may otherwise have sounded too far-fetched to believe.

BOOK 1

1

JOURNEY OUT

One morning early in 1959 two well-dressed and nicely spoken ladies from the Fairbridge Society came to see us in our small council house on the Langney estate outside Eastbourne in Sussex. A few weeks before, we’d had a visit from the local Fairbridge ‘honorary secretary’ and she had now brought down a very important person from the Fairbridge Society in London.

Sitting with Mum, we three boys were wearing our Sunday best. We were very poor: my mother was a single parent with four sons. Our oldest brother, Tony, was twenty and in the RAF. My twin brother, Richard, and I were twelve and Dudley had recently turned fourteen. The three of us were attending the local secondary school but Mum was finding it increasingly difficult to make ends meet, so there was little prospect of us staying on at school beyond the minimum school-leaving age.

The ladies from Fairbridge told us wonderful stories about Australia, and showed us brochures and photographs. The picture they painted was very attractive: we would be going to a land of milk and honey, where we could ride ponies to school and pluck abundant fruit from the trees growing by the side of the road.

They explained that Fairbridge had recently introduced a new plan called the One Parent Scheme whereby Mum could follow us out to Australia and we would be back together as a family in no time.

They were good salespeople. By the late 1950s Fairbridge had become a slick organisation with almost seventy ‘honorary secretaries’ spread throughout the UK, recruiting more children to its scheme.1 For a poor family like ours, the offer of free transport to Australia, then free accommodation and education once we got there, sounded almost too good to be true.

The ladies told Mum that however much she loved us, she couldn’t provide us with the opportunities we would be given at the Fairbridge Farm School in Australia. They gave us brochures, one of which read:

In Britain many thousands of children through circumstances and the bad environment in which they are forced to spend formative years of their childhood are deprived of the opportunity of a happy, healthy and sound upbringing and are allowed to go to waste.

We believe that a large number of these boys and girls (plus a parent where there is one) would have a far greater chance in life if they are taken out of the wretched conditions in which they live, and given a new start in life in the Commonwealth at establishments like our existing Fairbridge Farm Schools.

. . . Here they can exchange bad and cheerless homes set in drab and murky surroundings of the back street . . . for a clean and well kept home, good food and plenty of it, and fresh air, sunshine and myriad interests and beauties of the countryside.

. . . Here they are given the love and care which many of them have never known.2

They told us we qualified for Fairbridge.

We were almost the perfect catch for them: three healthy boys, all above average intelligence, from a deprived background. We were, however, a bit older than the ideal age, as Fairbridge preferred children no older than eight or nine. They felt there was a better chance of turning younger children into good citizens because they’d had less exposure to low-class society.

Ironically, the Fairbridge children who would do better in life tended to be those who entered when they were older, and stayed there for the shortest period of time. The ones who would struggle through life tended to be those who spent their entire childhood in the care of the farm school.

We were like most other Fairbridge children in that we came from a deprived background. Our mother, Kathleen Bow, was born into a modest, working-class family during World War I in Bruxburn, about twenty-four kilometres from Edinburgh, in Scotland. Her father went to war in 1914 and was gassed in the trenches of France before being pensioned out of the army. Her mother worked as a nurse in the Bangor Hospital, to which the wounded were brought, usually from the hospital ships that berthed on Scotland’s Forth River. It was said that many of the men were so terribly wounded that they were brought from the ships to the hospital at night so as not to panic the civilian population.

Mum was illegitimate and when her mother moved to Glasgow to marry a badly wounded soldier she had nursed – her second marriage – Mum was left to be brought up by her grandmother with two children from the first marriage. Mum used to say that she thought her gran was actually her mother, and she only learnt the truth after Granma McNally died when Mum was about fourteen years old.

With nowhere else to go, Mum went to work in one of the big houses in Surrey, in the south of England, living very much ‘below stairs’ as a domestic servant. Within a couple of years she had married local builder Bill Hill and in 1937 she gave birth to Tony, who was to be the first of five sons. In 1940, Billy was born but died of meningitis within months. Dudley was born in 1944.

By the time Mum was pregnant with me and Richard she was separated from her husband and had been abandoned by her partner. At that stage, she was working in a big house in Hertfordshire, but as her pregnancy developed it became clear she would have to leave. She was taken in by a vicar in Eastbourne, Sussex, and lived in the basement of the vicarage till we were born.

So, we were born in 1946, when being a single mother or a divorcee still carried a stigma. Throughout our childhood we were instructed to tell people that Mum was a widow, even though we, along with everyone else in our village, knew it didn’t ring true.

For the first six or seven years of my life we survived on charity, welfare and the small income Mum generated working whenever she had the chance while caring for four children. We lived in three rooms on the second storey of a small terrace house in Dersley Road, Eastbourne. It was a very poor and rough neighbourhood with a sullied reputation. The local council, in an effort to tidy up the street’s image, changed its name from Dennis Road shortly after we moved there.

The three-room flat had a coal-fired stove, which was used for cooking and heating. There was no bath, but in the kitchen there was a large stone sink, which for all our early childhood doubled as a bath for Richard, Dudley and me. We would sit on the draining board with our feet in the water and wash ourselves as best we could. Mum and Tony would bring the tin bath in from out the back of the house, lug it up the stairs, heat water on the stove and take a bath in the tiny living room. We didn’t have a toilet so we paraded down the stairs and through Mrs Symes’s flat on the ground floor below, carrying our potties though her living area and kitchen to the toilet out the back.

In the early postwar years we still had gas street lamps. Every night the gasman came with a long pole to ignite the flame, and he returned early the next morning to douse it. Everyone around us was poor. We were all still issued with ration books full of coupons to go toward paying for food. An old lady across the road used to give us her sweets ration coupons, even though we didn’t have enough money to use them anyway. It was a common occurrence just before payday for a child to go to their neighbour’s house with an empty cup to borrow half a cup of sugar, flour or milk. Seldom did you ask for a whole cupful for fear the neighbour wouldn’t have enough – or that you wouldn’t be able to pay it all back. Shearer’s, the little grocery store on the corner, would run up a slate for each family so they could buy food between paydays, but on more than one occasion they had to halt our credit because Mum was continuing to run up a tab though she was unable to pay anything off.

From a very early age we learnt how to get ourselves to school and care for ourselves in the afternoons, because Mum took any work she could get. From the age of about ten, Tony had to help look after us, and at eleven he got a job at weekends and during the school holidays in the local fishmonger’s. He would come home smelling so strongly of fish that Mum would insist he change his clothes outside our little flat – but we had more fish to eat than any of our neighbours, even if it was the leftovers they couldn’t sell in the fish shop.

Dudley, Richard and I were all doing reasonably well at Bourne Junior School. Tony had already sat for his Eleven Plus exam and won a place at the Eastbourne Grammar School. Dudley and Richard always managed to be in the A classes, but I tended to lag behind in the B classes. Our school, like most in those days, was a dark and oppressive building with equally severe, bleak teachers. School was not much fun, but it wasn’t designed to be.

As all the other kids did, we played in the streets or on one of the many bombsites in the neighbourhood. Eastbourne had not been a major target during the war but it was said that after raids the German bombers would drop off any bombs there that they had left on board, before returning over the English coast.

One of the more popular games played by the kids in the narrow back lanes of the terrace houses was a form of badminton, using an old shuttlecock and hardcover books for racquets. Eastbourne has always been a popular beach resort so we spent a lot of time during the short swimming season up near the Eastbourne Pier. The tourists created job opportunities for Mum, who worked at different times as a domestic in one of the hotels, in beachfront tourist shops, and as a waitress in a coffee shop or in one of the better hotels. Sometimes she came home to tell us she had seen someone famous at work. Once it was the Duke of Edinburgh, whom she had seen at the top table of a banquet at the Grand Hotel up near Beachy Head, while she was working as a waitress on the bottom tables. Another time it was Billy Wright, the then England football captain, whom she served coffee to in the café at Bobby’s department store. We were terribly upset that she didn’t get his autograph, and even more upset when she said she hadn’t known who he was until the other waitresses told her.

When Mum was sick or there was some crisis, we would be put into children’s homes, but would always come back together as a family as soon as things stabilised. As we got older it became increasingly difficult for the five of us to live in three tiny rooms. When we were six years old, Richard and I were put into a giant Barnardo’s children’s home in Barkingside, Essex, while we were found slightly bigger accommodation. It was a tough and traumatic experience. I can remember being teased and bullied by the other children when we tried to write a letter to our mum – it seemed they didn’t have mums to write to.

After some months we were reunited with the rest of our family in a new home. We had a five-room flat in a big, dilapidated old Victorian house in Terminus Place, Eastbourne that had been converted into a number of smaller welfare apartments. I can still remember the day Mum came to get us from Barnardo’s, her excitement on the train trip back to Eastbourne, and our arrival in the early evening to see Tony and Dudley cooking up a pan of bacon and eggs for our tea. There were a number of families living in the grand old house. Years later I would be reminded of it while watching the David Lean film Dr Zhivago: when Zhivago came back from the war he found the large house owned by his father-in-law’s family had been broken up into small apartments for fourteen families.

When I was about eight years old we moved into a new house on a council estate outside Eastbourne. The new village had been built on land reclaimed by the government from the estate of an old aristocratic land-owning family, the Austins. At last we had a home with an indoor bathroom and toilet. It had a large living room, kitchen and coal shed downstairs, and three bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs. There was one fireplace and chimney in the centre of the living room that heated upstairs and downstairs, and also heated the water.

Our improved circumstances were part of the marvel of Britain’s postwar welfare state, initiated by the British Labour Government. It was much maligned in later times, but this phenomenally successful social experiment meant that for the first time all classes of people were assured of basic food, shelter and clothing, and some level of health care and education. Prior to the welfare state most Britons lived and died poor, in a land of appalling class rigidity and social inequality where there was virtually no prospect of social mobility.

By now Tony had left school and was working and paying Mum a big part of his wages, which helped a great deal. We were still very poor but most of our neighbours in Langney village were only slightly better off. In those days you paid for electricity as you used it, by putting a shilling in the meter under the stairs. Often we went to bed early on a Wednesday night because the last shilling ran out or we had no more coal to put in the fireplace until payday the next day. Despite a lack of money, Mum somehow always managed to put food on the table.

Being on the edge of Eastbourne, Langney village was a pretty good place for kids. We lived in a semi-rural environment and spent lots of time playing in the fields or on the ‘crumbles’, a vast stretch of pebbled beach between Eastbourne and Langney, where the pillboxes and concrete tank blocks built in 1940 in anticipation of Hitler’s invasion of Britain were still standing. A little over a mile from the village was Pevensey Castle. On the site there was an outer Roman wall built in 300 AD, a Norman keep and a medieval castle with drawbridge and moat. It was a favourite location for playing and camping with the Boy Scouts, and has remained a favourite spot for me throughout my life.

Television had already been in Britain for a few years but no one in Langney could afford to buy one until the late 1950s, so community activity survived. It seems everyone was either in the Boy Scouts, Civil Defence Corps, the drama club or one of myriad other communal activities. Throughout the year the village would turn out for special and festive occasions, including the annual fete. On Guy Fawkes Night we would all march in a torch-lit procession around the village before lighting a huge bonfire in the park at the bottom of Priory Road and letting off fireworks.

Christmas was especially good as people helped one another as best they could. Mr Fry – who lived down on the next corner, had five kids and drove a vegetable truck for a living – would always leave a basket of fruit on our front doorstep. Mrs Austin, one of the landed gentry who still lived in the big family house on nearby Langney Rise, used to leave a sack of potatoes. She didn’t mind when her son Philip came round to play with us lower-class kids when he was home from his exclusive boarding school.

We finished our primary education in a school built as part of the Langney village, then went on to Bishop Bell Secondary Modern, which was also built to cater for the increasing number of postwar baby-boom children.

By the time Dudley, Richard and I reached secondary school our eldest brother, Tony, was in the Royal Air Force. Britain still had conscription in the 1950s and Tony, who as a boy had been a member of the boys’ Air Training Corps, decided to do his national service in the RAF. He signed up for five years instead of the standard two. Conscripts were paid only a tiny allowance, but by signing up for a longer period, Tony was able to earn enough as a regular to continue to send money home to help Mum. Nevertheless, as the rest of us boys were getting older it was becoming increasingly obvious that Mum would not be able to afford to keep us at school beyond the minimum school-leaving age of fifteen.

Some years before, a woman who lived out the back from us in Dersley Road and who was struggling on her own had sent her three boys out to Australia with one of the child migration schemes. She was able to boast that her sons had done well for themselves: the eldest had become a policeman and where we came from that constituted considerable social mobility.

Several things were weighing heavily on Mum’s mind. There was a recession in Britain in the late 1950s and jobs were hard to get, so she was concerned about our poor prospects if we stayed in England. At the same time, Australia was promoting itself as the land of golden opportunity where jobs were plentiful. Years later she would reveal that she was also concerned about conscription and the risk that we would have to go to war. In the mid to late 1950s Britain was involved in the ‘troubles’ in Malaysia, the Suez crisis, and one of the boys we knew had been killed while a national serviceman in Cyprus. Mum’s family had been split up in World War I, her own family fell apart during and after World War II, and she didn’t want to see further family disruption.

When the day came for us to go around the village and say our goodbyes to all our friends and neighbours, it was very sad. It was the first time I recall having to say goodbye to people I was close to, knowing I would probably never see them again.

Then I was on the train with Mum and my two brothers to Knockholt in Kent. Fairbridge owned a house there, at which children would gather in a group before sailing out to Australia. We were a little anxious about our journey into the unknown, but as young boys we were also excited about embarking on an adventure, sailing to the other side of the world. I remember Mum being filled with sadness when she left us that night to go back home. She would remain unsettled until our little family was back together three years later.

We were all amazed at our magnificent new home in Kent, as we had never experienced such fineness and luxury. We were told that Fairbridge had bought the house with money donated by a woman whose son had disappeared after being parachuted into German-occupied France in World War II with the British Secret Service. It was presumed he had been captured and executed. His mother had wanted the house named in his memory, so it was called John Howard Mitchell House.

It was an imposing two-storey mansion, with an attic and cellars, gardener’s lodge, squash court and stables. There seemed to be countless rooms, including a large library, banquet room, billiard room and bathrooms upstairs and downstairs. Outside there were orchards and vegetable gardens and rolling green fields that seemed to go on for ever.

There was a matron and her assistant, a cook, a gardener and a cleaner who came every day. Between them, they catered for our every need. They cooked our meals, ran our baths, bathed the smaller children, laundered, ironed and laid out our clean clothes, and made our beds. We spent three weeks at Knockholt in beautiful springtime weather. We played all day, as we were not sent to school and not assigned any work.

Ian ‘Smiley’ Bayliff was at Knockholt in 1955 as an eight-year-old, with his three brothers, and remembers it as the best time of his life:

I remember it very, very well. Lovely place, something out of a book. The food was absolutely beautiful, you know. We’d come from a very poor family; we were just as poor as church mice. We were that poor the church mice moved out. So coming down to Knockholt . . . there was food, there was three meals a day – breakfast, lunch, tea – there was afternoon tea, there was room to move – almost had your own bathroom there were so many bathrooms in the place. It was warm; you always had plenty of clothes.

. . . We were there for two months and really loved it and it was the best Christmas of my life. It was sort of what you would expect at a big, rich country mansion.