Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

All I am is a fisherman. That's all I'm guilty of, Your Honour. On 31 May 2010 eleven holdalls were discovered along the shore near Freshwater on the Isle of Wight; when opened they contained £53m worth of cocaine – the biggest haul ever found in UK waters. A local fishing crew was accused of waiting in the Channel for the bags to be thrown from a passing cargo ship in an operation allegedly masterminded by a local scaffolder. The Freshwater Five is a true story that cuts to the heart of the British judicial system. Did five men really attempt one of the world's biggest drug smuggling operations – or were they simply in the wrong place, at the wrong time? Why did the police hastily alter key surveillance statements, why were logs blacked out or mysteriously left empty – and why was crucial evidence never disclosed at trial? All five men fiercely denied the allegations, but a jury rejected their version of the events. This is the story of what actually happened as told by the skipper of the crew. It's a story that reveals the human misery of brutal prison sentences and a story that leaves the reader with one question: Does the British legal system really dispense justice?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

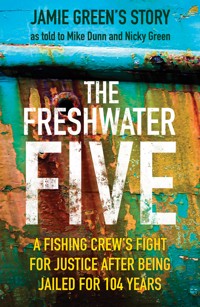

Front cover: the Galwad-Y-Mor (©Nicky Green)

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mike Dunn and Nicky Green, 2021

The right of Mike Dunn and Nicky Green to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9455 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1 The Arrest

2 Hooked

3 ‘Mor’ the Merrier

4 Russian Roulette

5 Nikki’s Sentence

6 Held at Gunpoint

7 ‘You’re up to Running Drugs’

8 Hard Labour

9 Vic

10 Ships in the Night

11 Black Objects

12 Prison

13 Torn Apart

14 Did You Do it?

15 Ghost Plane

16 Don’t Upset the Police

17 Altered Statements

18 Coopering

19 They’d Never Lie

20 Mr Anything-is-Possible

21 Tied up in Knots

22 It’s Impossible

23 Spoilt

24 Who’s that Man?

25 The Verdict

26 5 Men, 104 Years

27 Rigged

28 Terrorists

29 Innocent from Every Angle

30 The Missing Log

31 Fighting Back

32 Named and Shamed

33 Handcuffed in the Pulpit

34 Victims

35 Proving Our Innocence

36 Failures

37 The White Ember

38 Non-Disclosure

39 The Promise

Support the Fight for Justice

About the Author

Chapter 1

THE ARREST

I never saw the violence coming; I never saw the first arm lash out. I just felt a numb pain shivering through my body as the blow connected across my exposed throat and neck.

I never anticipated the rugby tackle, either, the one that must have sent me crashing to the floor. I was hauled down in seconds, everything suddenly upended, nothing making sense. What the fuck?

I heard angry, menacing voices barbed with threats. Someone barked: ‘You … don’t move.’ I tried to tilt my face upwards but an oversized palm instantly pressed heavily into my right cheek, grinding down, bone against bone, until the left side of my face felt like it was being forcibly squashed into the wooden decking below. That hurt.

My heart started pounding so ferociously it felt ready to explode at any moment; I gasped frantically for air but my rapid, panic-fuelled gulps weren’t enough to calm me down.

‘What the hell?’ I yelled. ‘What’s all this?’

I could sense tightening grips around my ankles and arms and I could feel a crushing weight in the small of my back, like three or four sumo wrestlers had decided to pin me down. Their combined weight made movement impossible. I tried desperately to wriggle clear but the more I squirmed, the heavier the pressure on my back and the tighter the grips on my immobile limbs. Shit, these guys mean business.

There must have been around twelve of them. Moments earlier, I’d watched them approaching, blokes dressed casually in jeans with designer shirts hanging over their arses, and I thought to myself ‘bloody yachties, why do they always come down the wrong pontoon?’ I even shouted over: ‘You can’t come down here, this is private.’

Dan and I had finished off at the Galwad and were just messing around, having a giggle. Vic was around somewhere although I didn’t care where. I’d had enough of him. Scott had already headed off to the restaurant with a basket of lobsters. I’d told him to pick out the best because Maisy had booked a table. Her boyfriend’s parents were over and she wanted to impress them. Dan had just kicked the fish pen back into the water and we were heading back to the quay as the blokes walked towards us.

I remember turning to Dan, just behind me, and muttering: ‘Just look at these tossers.’ I even gave them another warning: ‘Hoy, you can’t come down here, this is for the fishing crews only.’ But they kept on walking – and that’s when the arms suddenly lashed out and, within the blink of an eye, I was poleaxed on the pontoon floor.

‘Fuck off,’ I yelled. ‘Who the hell are you lot?’

One of them – the one still pressing his hand down into my cheek – lowered his head closer. I could feel his stale breath pouring over my face and into my nostrils as he spat: ‘Police … you’re under arrest.’ As he said that, I watched legs and boots running past me. They were going for Dan, too.

Next, I felt my arms being bent back and cold steel pressing against my wrists. I was being cuffed. There was nothing I could do, I was practically paralysed and totally at their mercy. So I carried on cursing and swearing because it was the only resistance I had left. ‘What the fuckin’ hell is this shit all about?’

Once they were happy I couldn’t take a swipe at them, I was dragged back up to my feet. Two of them were now gripping the back of my arms, real tight, until it felt like their hands would leave permanent indentations in my skin. ‘You’ll find out soon enough,’ someone said, as I was half dragged along the pontoon towards the main quay area, just in front of where the Wightlink ferry to Lymington gets moored. For a fleeting second, I got a clear glimpse of his face and thought: ‘I know you, don’t I?’ But I couldn’t think why, or where from.

Once we reached the quay area, I was hauled over to a bench, close to the toilet block – where the old, grey waste-oil tank used to stand, close to the Wheatsheaf pub. I got the impression the police wanted me out of sight; it was a Bank Holiday weekend, around 9 p.m. on Sunday night, and there were plenty of pissed-up holidaymakers and day trippers milling around, some of them with pints in their hands, others holding kids or queuing in cars for the next ferry back to the mainland.

Another copper came over – it was a warm evening by now and he was wearing dark shorts. His legs looked pasty white and ludicrous. It just added to my suspicion that the whole thing was a joke.

‘Mr Green?’ he asked, although it was pretty obvious he knew damn well who I was.

‘Yeah?’

‘You’re under arrest for importing class-A drugs.’

That really ignited the touch paper. ‘You having a laugh or something?’ I replied. ‘You wankers are pissing in the wind. What the fuck’s your game then?’

I carried on swearing and cursing and shaking my head from side to side, wriggling manically, desperately hoping – I guess – that my cuffs would miraculously spring apart.

‘We’re SOCA – the serious crime agency,’ he replied. He was stood, towering above me, yet even then I still looked up to his eyes just in case there was a hint of mischief in there somewhere. ‘Do me a fuckin’ favour,’ I replied. ‘Tell me straight, is this is a bloody joke?’

‘No,’ he replied. ‘Importation of drugs – cocaine.’

‘What?’ I yelled. It suddenly dawned on me there was absolutely no sign of Dan – or Vic for that matter – and, as I looked over towards the quay, I could see the Galwad was now ablaze with lights. The blokes who had upended me on the pontoon were crawling all over the deck. ‘What are those dozy twats doing on my boat?’ I screamed. Deep down, a part of me wanted an audience; I was hoping the holidaymakers would hear my cries and come over to see what all the fuss was about.

The copper clearly sensed I was playing up. Within seconds, a couple of his colleagues turned up and I was frogmarched into a nearby car and shovelled on to the back seat. The doors were clicked shut; one of them sat next to me, the other in the front.

We sat there for at least a couple of hours. Eventually I packed in swearing and cursing and trying to cause a commotion and instead fell quiet. Why did they suspect me of this? Was it because I’d been out on the Galwad? There’d been a plane – I’d seen a plane – first through the gaps in the Needles, then – again – as we came back into the Solent. Was that something to do with it? And there’d been boats, out on the horizon. What were they doing there? I needed to relive the last thirty hours in my mind. What had happened, what on earth had I done, to suddenly be in this mess?

Immediately my mind focussed on Vic, or rather the two strangers he’d turned up with. I hadn’t been expecting them. I couldn’t even remember their names – one was called Dexsa, or something stupid like that. Were they somehow involved in this? If so, why? And how? It was impossible to make any sense of it, especially as Vic had done nothing but puke up the entire time.

OK, he was clearly no fisherman. But he’d been with me throughout and vomited to the point of begging me to make calls in the hope he could somehow get off the boat. The more I dwelt on that, the more convinced I was that he’d been simply trying to get work here illegally. What’s that got to do with cocaine?

Just as all this was whirling around in my mind, a penny suddenly dropped. I realised who the bloke on the pontoon was when they all jumped me. I knew I’d seen him before and now I realised where.

He was one of the armed police officers who’d held me and Nikki up at Lymington. I can still see his fuckin’ revolver poking out of the holster hanging lopsided against his hip.

Now, it was beginning to make sense. My name was on their system and someone had it in for me.

Chapter 2

HOOKED

I was hooked from the age of 8. Even when I was an angry, rebellious teenager who just wanted to get pissed and have a punch-up, fishing reeled me back in, time and again. Hell, I even studied it at college where, for once in my life, I actually shone academically. I was good at something.

Grandad Cyril introduced me to fishing when I was still at primary school. We’d go sit on Ryde pier, rod and line fishing for hours on end. He wasn’t a fisherman by trade – he was a signwriter on the trains – but angling was his hobby and he taught me all the basics: how to set up a rod, what worms to use and all the different types of bait, and where we could land a bit of mackerel. He taught me about patience and he taught me how to be skilled. Sometimes I’d be transfixed by the speed of his hands, all gnarled and lined with age and yet incredibly quick and deft as he changed bait or reeled in a catch.

Sometimes we’d get a few pollock off the pier but the real fuck-me moment would be if one of us caught a seabass. I can still hear us whooping and cheering when that happened. I can still see his toothless, cheesy grin. The thrill never left him despite his age. I was a teenager when he passed away and that’s when I inherited most of his gear. By then, a few of my mates had also picked up fishing and we’d go down the beach in the evenings and spend all night with the old tilly lights casting their yellowy glow over the water. Happy days.

I’d always been outdoorsy right from childhood. School wasn’t for me – I preferred to go rabbiting and ferreting. Sometimes I’d skip lessons altogether and go fishing with a family friend, Charlie Bishop, who used to do a bit of small boat fishing with nets. My old man, who was a builder but also loved fishing, would occasionally join us, too.

I’d be about 15 years old by then. Another of my dad’s pals, Jeff Williams, had a slightly bigger boat – a 27-footer that could handle rougher weather – and I’d go out with him in the winter months. It was Charlie, though, who persuaded us to get our own boat. He could see how captivated I was and one day, after we’d all been out, he turned to dad and I and said: ‘Look, I’ve still got an old boat I ain’t using over the other side of the island. Why don’t you paint it? I’ll give you some nets, and you can go dabble with it during the summer.’

It was only a 16-footer and although it looked a bit shipwrecked and abandoned under the cliffs, we pulled it out and gave it a nice shiny coat of blue paint. Then we’d drag it over the beach and get it out on to the water. Next, we made up some pots from old scrap reinforcing bars off dad’s building sites. We’d cut them up, weld them back together to make a D-shaped pot, which we’d wrap in netting. Then we’d create an entrance so the lobsters could climb in to get to the bait, and add some concrete at the bottom to weigh it down.

I guess I was learning the basics and something new nearly every day but I’d no idea where it was all leading until a careers’ advisor came to our school. I was in my last year and we all had to see him one by one. ‘So, Jamie, what do you want to do when you leave?’ he asked.

I was going through a cocky know-it-all stage at the time and was convinced career advisors could do sod all for me. ‘I want to be a fisherman,’ I replied, half smirking and thinking: What you going to do about that, then?

‘Ah, right’ he replied, and scribbled down some notes. Tosser. I thought no more about it, then, to my astonishment he returned about two weeks later and collared me outside our classroom. ‘Jamie. Jamie Green. I’ve got a college course for you.’

‘You what?!’ He explained there was a specialist YTS fishing course in Falmouth I could join. ‘It lasts four months, you’ll get £25 a week, and you’ll get digs arranged and paid for.’ Bloody hell.

I’ll never forget the look on my parents’ faces when I went home and announced: ‘I’m going to college!’

‘Get out of here, Jamie! You having a laugh with us? What college, where? Is this for real?’

‘Down in Falmouth. They’re even going to pay me!’

My parents were thrilled and I absolutely loved it. For the first time in my life, I was thriving in a classroom. I learned about boats, how to build them and how to strip out an engine, rebuild it and then keep it running. I’d always liked meddling around with old cars so the mechanical side of the course came easy. I learned about radio communications, areas to fish and what sort of fish you’d find and where. They told us how to make pots and nets and showed us proper knots and splicing for rope, as well as wire. Then we learnt about radars and mapping and handling weather and survival – even basics about business management. I gave it my all and ended up with a City and Guilds Distinction and some of the highest marks in college. It had never been like that for me at school.

I came back fired up and determined to build my own boat. My dad was up for it; we had pals who were building small fibreglass boats so we’d go along and watch how they did it. Our first proper boat was the Lizzy-Jo. We bought the shell, got it on a private slipway that we hired, then my old man employed a boat builder to customise it. I’d give him a hand and although I was only his gofer and labourer, I watched closely what he was doing.

I quickly understood the concept of fibreglassing, how to glass in the bulkheads and how to balance the right mix of resins, hardener and catalyst. Get that wrong and it’ll go off real quick. We needed a boat with a stable platform to stack pots and a winch to haul them in; a boat that could get us out 6 to 7 miles quickly and handle rough weather.

I already knew, though, there were better areas to fish beyond that. Areas where we could land the really big stuff. We’d often get visiting Channel Islands boats stopping off overnight on the island. Their crews would come in for a beer and I’d quiz them about where they fished and the areas they liked. What they said stuck in my mind – there was a whole world to exploit further out there.

I also realised there was good money to be made from building boats, registering them and selling them on at a profit. It was becoming increasingly hard to get fishing licences and we were able to sell Lizzy-Jo to a bloke who simply wanted the licence for a trawler he owned. We very quickly started building Lizzy-Jo 2 and by the time we’d sold that, we had enough money to build a catamaran – and get out beyond 6 miles.

I built the John Edward from fibreglass in 1996 and, compared to both Lizzy-Jos, it was the dog’s bollocks. Naturally, I stretched the rules. I couldn’t help myself. I wanted the catamaran to be bigger than was permitted. To get its licence, it had to measure 40ft, but I wanted longer. So I built long, pointed nose cones at the ends that could be hinged or bolted on – and detached when it came to physically measuring the length of the boat. I double-checked the rules, which clearly stated if attachments were detachable, they wouldn’t be included in the structural measurement.

It was measured and passed, and that seriously pissed off my rivals, who kicked up a right fuss. Sure enough, the authorities came back, saying: ‘We need to measure your boat again.’

‘What do you mean? You’ve measured it once, what you need to measure it again for?’

‘We need to double-check the length of it.’

I wasn’t having that but the silly bastards turned up in Yarmouth and actually tried to seize the boat off me. I had a massive row with some pen-pusher down on the quay; in fact, I got so angry I almost threw him into the water. The next I knew I was being served with a whole load of notices: I couldn’t go fishing, I couldn’t go out, I couldn’t use the boat, I couldn’t do this, I couldn’t do that.

That was a red rag. ‘Right,’ I bellowed. ‘I’m taking the bow sections off completely, then you can’t stop me.’

So that’s what I did. The boat looked ridiculous but it measured 40ft and was therefore legal. We’d go off into a head sea and the water would come crashing over the front, straight at us. But I carried on and everyone got the right hump about it. They couldn’t deny the John Edward was built to the maximum size permissible for its licence and, even with no nose cones, it remained quick and stable. It could handle loads of weather and it could carry loads of pots. Best of all, nobody else had anything like it.

The John Edward wasn’t perfect but it was a giant step forward. It had no facilities for overnighting, although sometimes we’d rough it and kip on two benches, down below at the back. It was always too damp and noisy down there to get any proper sleep, though.

I was in my own little bubble, earning a living, we had good times and we had some shit ones. Fishing goes in cycles like that. It was the mid-1990s, I was in my mid-20s and I had absolutely no inkling for anything else. I knew there were bigger and better areas to fish out there – but I hadn’t worked out how to reach them.

I hadn’t yet clapped my eyes on the Galwad.

Chapter 3

‘MOR’ THE MERRIER

The Galwad Y Mor was the world to me. I loved the fact its name was Welsh for The Call of the Sea. That sounded right. This wasn’t just a boat, this was my life – the tangible proof that my business was doing OK, that my family had food on the table, that we could pay our bills and afford wages for a crew. I’d even taken out a £100,000 mortgage to buy it. That’s how much it meant to me. I had a business plan and the Galwad was the embodiment of it, the heart and soul of everything I was and wanted to be.

I’ll never forget the first time I clapped my eyes on the Galwad. I didn’t own it then but I instinctively knew this was a boat I was destined to have. It was distinctive, with broad, horizontal stripes all the way round – dark Oxford blue immediately below the hand rails, then a vivid sky blue down to the water line. The top railings and wheelhouse were brilliant white and at the back, above its registration number, SU116, proudly stood the name Galwad Y Mor, printed in a posh, old-fashioned bright-red typeface.

I watched it sliding along the Solent and kept on watching it until it was no more than a distant dot on the horizon. That boat had everything I needed to expand my business – to take us into waters we couldn’t reach – areas beyond the shipping lanes and closer to France where nobody else from the island went and where we could land bigger and more profitable catches.

Better than that, though. I knew something more: the Galwad was a boat that was just like me. It broke all the rules. It stuck two fingers up to authority. I loved it even more because of that.

I’d watched it being built by a family on the mainland in Lymington and I knew it was bigger than the 12m it was actually licensed for. In the old days, boats used to be officially measured from the pin on the rudder (its rudder stock) to the bow. Builders literally stretched the rules by extending the length of their boats some 4ft beyond the rudder stuck so the bodywork stuck out at the back.

The Galwad was built around 1988 and when measured she reached a mighty 44ft. It was a monster! The rules were eventually changed so licences would only be issued to boats that measured 12m overall – but those already on the register had the right to remain.

To my knowledge there were only three boats left in the United Kingdom that could cheat the system like this – and the Galwad was one of them. In the business it’s known as Grandad’s Rights. Once a boat is over 12m, the rules state it can only fish outside 6 miles from the island. The Galwad was considerably longer – yet nobody could stop it fishing right up to the beach, or absolutely anywhere else it wanted!

That boat was everything I stood for: a great, big, floating ‘fuck off’ to the rules. That’s why I went after it. That’s why I begged the bank to give me the £100,000 mortgage. I mean, banks on the Isle of Wight aren’t exactly falling over themselves to lend you money to build a bloody boat. It’s not like going to Newlyn or Grimsby where fishing is the bedrock of the entire community. The Isle of Wight is more about tourism and yachties than sweaty fishermen like me.

There aren’t many of us left on the island fishing for a living. Go into a bank and say ‘I want to build a boat’ and their first reaction is to look at you like you’re ravin’ mad or something. But I showed them my turnover figures, my profits and costs, I talked to them about my business and how a new boat could help us expand big time. It wasn’t easy for them – but they got it. They could see where I was taking my business and they knew I’d be out until Christ knows what time, seven days a week, to make it happen.

I also knew it would seriously piss off all my rival fishermen on the island. Even when I was arrested the local boats went straight to the fisheries office in Poole and tried to get the Galwad kicked out to 6 miles.

‘It’s too bloody big that boat, get it out,’ they bleated. But the fisheries officer was stumped. All he could say was: ‘Sorry, there’s nothing we can do about it, it’s under 12 metres from when it was built.’

Yes. That’s why I bought the Galwad. It empowered me.

I’d just got into fishing as a livelihood when the Galwad was being built. But I was always at the mercy of the weather and how far out I could safely go. Winter would be too rough, which meant we’d be grounded and couldn’t earn. My boat then – which I built – had no accommodation and no real cooking facilities. It had deck tanks to store product but they could only hold a ton and a quarter. Then I’d be full and we’d have to head back.

The Galwad, however, held 7 tons. It even had a vivier tank that pumped sea water through constantly, keeping the crab and lobsters alive and fresh – allowing me to stay out for as long as I wanted. It also had accommodation for five, a little shower and a proper galley. There was no toilet but that was a minor detail for us. We were used to either pissing over the side or crapping in a black plastic bucket.

Strange to think this detail would actually be debated in court years later as the police tried to shit all over us.

The Galwad went on sale in 2008 but I couldn’t raise the money quickly enough and lost out to a fisherman up in the Shetlands. I knew the new owner’s name, though. I got his number and rang him every couple of months or so, saying: ‘If you ever want to sell, give me a call.’

Finally, in November the following year, he said, ‘yes’, so I headed up to Scotland, putting my own boat on the market in the hope I’d get a swift sale and have the cash to help pay for the Galwad. We haggled, the boat had deteriorated and needed work, but we finally agreed on £120,000. I thought that was fair-ish – he’d wanted 130 grand to start. Plus, a high side had been added that would protect us against crashing waves and help us work out on deck in bad weather.

I managed to sell my boat in time but I still needed the £100,000 mortgage to make up the difference. It didn’t frighten me, though, because I knew it was my future. This was everything I wanted: if we put in the graft, we’d earn the money. I knew we’d be all right. I had the confidence.

I’m sure every skipper – when they’ve changed boats for something bigger and better – has that moment when he thinks ‘I’ve made it.’ That’s what I was thinking as we headed back to the island in the Galwad for the first time. ‘I’ve had to duck and dive but I’ve got here. I’ve taken on finance, I’ve put my neck on the line but I’m out here. I’ve done it, I’m up and running. This is going to be our year and we’re going to earn a bit of serious money.’ That’s what I was thinking.

Usually, you’re apprehensive steering a new boat for the first time. You have to get a feel for it, develop confidence and understand how it’s going to handle, especially in weather. You have to get to know one another.

I instinctively knew the Galwad. We were connected already. It even had its own satellite phone – clapped out but even so, a step up from what I was used to.

I’d still got some money left over so I installed an Olex unit almost straight away. This was relatively new technology at the time but I knew, if I could master it, it would not only track my course, it would enable me to see 3D images of the seabed. This was massively important for me and cut to the core of everything I was aspiring towards.

On my other boats, I’d made do with an entirely inadequate echo sounder. Whenever we went to fresh grounds, we were practically fishing in the dark with no accurate picture of what was beneath us.

The Olex could change all that. Its monitor would let me build an image of the seabed below so I could see all the lumps and bumps. It enabled me to find hotspots other fishermen wouldn’t know about, to open up grounds that would be good to fish. The craggier the seabed, the better. The unit had a basic, default template of what it assumed the seabed would look like. By repeatedly steaming up and down and over and over the same area, the Olex kept updating what it saw below, adding the new information to the template. The more I kept going over a piece of ground, the more accurate the picture on the monitor became until it looked entirely different from what it had started with.

The combination of this new-fangled device and the Galwad really was my dream ticket. The Galwad enabled us to have longer trips; the Olex empowered me to chart the seabed so I could physically see for myself the areas to go for. It was everything I wanted but it was also a lot to learn. I didn’t know anyone with an Olex so I had to teach myself how to use it.

I desperately wanted to master everything it could do. The more I could understand it, the more information it could give me – and that could be invaluable. I knew it could transform my business so, when we were out at sea, I’d spend as much time as possible in the Galwad’s wheelhouse playing with the Olex – while my crew were doing all the manual work on deck.

Looking for new ground was an all-consuming obsession, even before the Galwad. Fishermen always have to be on the move. You can’t stay in the same places because once you’ve taken the cream off a new area, you’re then fishing down and you don’t get a good enough return. You always want fresh ground, then – after roughly two weeks there – you move on. The question was always the same: ‘where next?’

The Olex would help me answer that by giving me a fuller insight into the ground and, because the Galwad enabled us to stay out longer, it gave me more time to map out an area while the lads got on with hauling in pots and shooting new lines.

The Olex I bought back then in 2009 was a bit like mobile phones were in their infancy – cumbersome and not very user-friendly. Today, they’re streamlined, even more hi-tech and there isn’t a credible boat on the water that doesn’t have one.

My previous boat – the one I’d sold to help pay for the Galwad – was a catamaran and had no such electronic luxuries. It was more like a raft, banging up and down on top of the water. In weather, it’d literally shake your fillings out. If we hit a 40ft block of water, it’d be like driving into a brick wall. I’ve had lads out there petrified the boat would fall apart.

The Galwad was a completely different animal. It would roll, but its movements were a lot more conventional. It could handle steering straight into the waves without frightening my crew to death. It was steady rather than fast and could cruise comfortably between 5 and 8 knots.

It was still early days in a new boat, though, and we didn’t always win. Winter 2009 was closing in and sometimes we’d come back almost empty handed. They’d be the worst days because the crew would still want paying and the restaurant would want its lobsters. Then there was the time when we had to call out the lifeboat.

We’d gone out to recover some pots. The weather was atrocious; when we eventually reached them, the back line, as we call it, had wrapped up on the seabed. The only option was to break the rope but when we did, it immediately shot straight back up and wound itself into the Galwad’s propeller.

We were basically screwed. There was nothing we could do to untangle it; the Galwad was rolling around uncontrollably and the lifeboat was our only option. It was late at night, hell, it’s still embarrassing to even think about it; fishermen aren’t supposed to call for help.

We were 30 miles out, the weather was really shitty, so I phoned the coastguard. What a humiliating conversation that was. They had to scramble a crew and there’d be no glory in it for them. Just a wretched all-nighter. It took them about an hour and a half to reach us, and then six hours to tow us back. By the time they rounded the Needles all of them, bar two, were spewing their heads off.

There were many other times, though, when the weather was blowing its arse out but instead of turning round – as we’d done before – the Galwad enabled us to carry on. We’d come home round the Needles with a really good catch on board – maybe 2 tons of crabs and some decent lobsters – and I’d feel my chest pushing out and a little grin spreading across my face as Yarmouth came into view. I’d be proud of the crew and proud of what my family had achieved. There really was no finer feeling than that. That’s what it was all about.

Chapter 4

RUSSIAN ROULETTE

I know what it’s like to be hit by a cargo ship. I’ve never been so terrified in my life.

It still gives me shivers to think about it. A lad and I were out on the catamaran, fishing a lump of ground north of Cherbourg, close to the Westbound shipping lane. I was knackered and said, ‘Take the wheel for a few minutes will you, while I get some kip.’ I was so tired I didn’t clock that he was barely awake himself.

I got down to my bunk and was slowly dozing off when suddenly I heard a high-pitched screech – so loud I can still hear it to this day. Everything plunged into darkness, the engine pitch switched from its familiar, contented hum to a piercing whine and I could sense the boat was no longer moving in the direction it was supposed to.

The screeching got worse and worse until the catamaran’s skin was reverberating with the sickening sound of metal rubbing angrily against metal. It was like being stuck in a horror movie: I felt as though I was inside a waste-collection lorry that was about to clamp its enormous metal jaws shut at any moment and crush everything inside into a tiny ball of mangled fibreglass and metal.

I leapt off my bunk and clambered straight out the back door on to the deck at the rear of the boat, ready to take my chances and leap straight out into the Channel’s freezing, black water. Something was seriously wrong, I’d never experienced or heard anything like it before but, as I hoisted myself on to the deck, I instinctively looked up.

It was like the world had been blanked out: all I could see was the arse end of a huge cargo ship, utterly obliterating the horizon as it towered over us, leaving behind a huge churning mass of boiling water that was tossing us around like we were a leaf in a hurricane.

I looked to the front of our boat: its crumpled nose told me instantly what had happened. The cargo ship had clearly pinched the front of the catamaran, pulled us around 90 degrees and then slammed us back into its rear end as it ploughed on. We were lucky, though. This particular ship had rounded cheeks at the back, so when we collided, the impact was slightly cushioned. If we’d hit it in the middle, we’d have sunk – probably without trace. Although the cargo ship pushed us down in the water as it carried on past us, it also let us go, dragging us further around in the process.

I found my mate, who was stood in a daze, barely moving, his jaw God knows how many fathoms below the water. Even in the dark, I could see his skin looked as white as a sheet. ‘How the fuck did that happen?’ I yelled, but he was too shell-shocked to speak.

Then I scrambled around lifting hatches to make sure we weren’t sinking. Chunks had been ripped off the front but – as I desperately tried to push them back into jagged holes and gaps – I realised there was no sign that we were going under. The relief in that moment was overwhelming. It felt like we’d miraculously survived a bomb blast – and, as my senses clicked back into place and the adrenalin started to surge through my veins, I noticed the cargo ship slowly disappearing from sight and yelled: ‘You didn’t get us, you bastard!’

Deep down, I knew it hadn’t got the faintest clue we were even there. That was the scariest bit.

It didn’t half teach me a lesson. I was irresistibly drawn to the Channel’s shipping lanes. There are two of them – Westbound and Eastbound. In many ways, they’re a bit like a giant M25 of the seas, an endless procession of huge, hulking ships – like great, big, articulated lorries – ploughing up and down, weaving in and out, slaloming with each other and pushing their heaving engines ferociously as they carry colossal crates and cargo, usually between mainland Europe and the entire American continent.

Between the two lanes is a 5-mile stretch of sea, a bit like the central reservation on a motorway I suppose. I call it the separation zone and it’s somewhere very few fishermen are prepared to enter, mainly because their boats aren’t big enough to reach that far – and they don’t want to run the risk of smashing into a passing container ship like we had.

The alarm bells always rang in my head whenever I saw one of these big beasts in the area. I’d see them approaching as we’d be heading north to south, pulling pots, and I’d watch them closely, thinking, They’ll see us in a moment, they’ll have someone on watch, they can’t miss us, surely?

It was a bit like a game of cat and mouse but the rule of the sea is simple and universal: they have to give way to fishing boats. So long as they see us, that is.

Sometimes my nerve would crack and I’d get on to Channel 16 – a communication frequency every boat tunes in to – and, even though I wouldn’t know the cargo ship’s name, I’d say something like, ‘This is fishing vessel Galwad Y Mor, this is my position (my latitude and longitude) – you are to my starboard side, 1.5 miles off, travelling at a speed of 15 knots. Please give way, we are a fishing vessel in the process of retrieving crab pots. Please respond on Channel 16.’

They have to give way to us. It’s the law. Sometimes they come back straight away, saying: ‘Hi mate, yeah we see you, you’re fine, we’ll come across your bow.’ When they make that contact, you know it’s all OK and you can breathe freely again. But sometimes they don’t come back to you at all and you’re thinking, Has this fucker seen me?

Then you have a right dilemma. You still carry on hauling the pots because that’s the business and there’s money at stake, but you definitely slow down a bit and get back on the radio. If that fails, you finally call the Solent coastguard. ‘Fishing vessel Galwad Y Mor here, I’m in position such and such, I’ve got a vessel 1.2 miles away from me, travelling this course, can you please try to raise him.’

Usually, when you call the coastguard like that on Channel 16, the cargo ship hears the call and suddenly bursts into life, mid-conversation. They’ll come in over the top of the coastguard, insisting: ‘Oh, fishing vessel Galwad Y Mor, yeah, we’ve seen you, there’s no problem.’

The last thing they want is the coastguard on their backs because they can get done for it. But even then, there are no guarantees.

Sometimes you get no response at all, even after you’ve alerted the coastguard. There have been times when I’ve stopped trawling, and I’m about to order Scott to cut the string of pots because we need to get out of the way quickly or else we’d be done for.

Cutting the rope is the last thing I want to do because that’s going to cost us time – and me money – to get it back later. It’s better, though, than seeing your buoys getting severed off their lines and watching months, if not years, of hard graft sink irretrievably.

It’s my call and sometimes we’ve been so close, the nippers have been on deck hooting and hollering at the cargo ship, even picking up crabs and hurling them in a bid to get noticed. Sometimes we’ve looked up to actually see the container crew waving back at us, smiling and laughing without a care in the world!

Christ, your old heart is racing and going ten to the dozen, and you’re cursing when that happens. It’s even worse in the middle of the night, or in a storm, or when there’s a dense fog out there and you can’t even see the end of your own boat. When it’s like that, I’m on the radio all the time, calling the coastguard and leaving absolutely nothing to chance.

Once you’ve actually experienced being hit by one of these bastards, you swear you’ll never let it happen again. In fact, I made damned sure it never did, especially once I’d got the Galwad.

After all, why would I take such an insane gamble with a boat I’d waited a lifetime to buy?

No, I’d never play Russian roulette with the Galwad just when it was about to turn my life around. I’d never take it out in a fierce storm and steer it perilously close to 66,500 tonnes of heaving steel ploughing past me at 20 knots.

Never.

Chapter 5

NIKKI’S SENTENCE

Sometimes I close my eyes and try to recall the good stuff: the laughs and the happiness and the love but it always ends the same way. A dark shadow creeps in and spreads and spreads until all that’s left – in cruel, vivid detail – is the moment my wife was told, ‘You have six months left to live.’

You what?

We were sat in a little office inside the island’s main hospital at Newport. Nikki’s oncologist was stood behind a desk stacked high with grey wire-mesh files stashed with piles of paper. It dawned on me that each piece of paper was a declaration of who got to live and who got to die.

The oncologist looked weary and uncomfortable and I wondered why she didn’t sit down like us. In front of her was an open report and she kept running a pen down the pages, pausing at certain points as if she were digesting some important information. Her face rarely looked up.

‘If we do nothing, you’ve got six months.’

She sounded calm, like it was a matter-of-fact sentence devoid of emotion. Silence filled the room; I turned to Nikki – her cheeks, usually bright and rosy, had instantly turned sickly white, her face frozen as the devastation sank in. Before we could react and protest and say surely there’s been a mistake, the oncologist continued.

‘However, if we get you straight on to chemotherapy then you might survive another year beyond that.’

You what?

It was January 2010. Four months later I was arrested. Back then, though, it was Nikki getting sentenced.

We walked out in a daze, holding hands ferociously, like we were desperately clinging on to the rest of our lives. In fact, I turned to Nikki and said: ‘Sorry luv, but I need to go back and hear that again.’

I found the specialist standing in one of those bleak-yet-functional hospital corridors, extra wide so trollies carrying bodies to operations and wards could be pushed down them. She was leaning against a grubby whitewashed wall, pock-marked with black smears where the trollies had no doubt scraped against them. She looked exhausted. Maybe telling us had knocked the stuffing out of her as well. I wasn’t in the mood for pleasantries, though.

‘What’s going on?’ I asked. ‘Are you telling me my wife has terminal cancer and the good side might be eighteen months if she takes the treatment, and the bad side is six months if she doesn’t?’

‘Yes, that’s correct.’

How could it be? My Nikki was indestructible. She had more balls than me. In fact, I called her ‘Stormin’ Norman’ because nothing – absolutely nothing – got in her way.

I first spotted Nikki when she was working in the Mary Rose pub in Ryde High Street. I was about 19 and a pisshead. I’d gone in with some mates, saw her behind the bar, and said to one of them: ‘Who’s that then, she’s a bit of all right, ain’t she.’

‘That’s my cousin. She’s called Nik,’ came the reply.

I kept finding reasons to drink in the Mary Rose after that and chatted to Nikki a few times as she pulled pints or cleaned up the bar. Eventually, I plucked up the courage to ask her out. Maybe it was some kind of sick omen, but two of our first ‘dates’ were spent in court. First, her cousin was up for fighting. He was given four years – a really big sentence on the island at the time. Then, not long after, I got into a ruck and had to go to court myself. ‘What you doing next week, Nik? How d’you fancy coming to court with me!’ Romantic, eh?

A year later, we got married. I was a different person by then – thanks to her. I’d been nabbed too many times, always for laddish stuff, half pissed and fighting with nippers from other towns. That’s what we did. At weekends we’d head for a nightclub somewhere on the other side of the island and half the time we’d end up in a ruck with the local lads.

Nobody got really hurt, it was all mouth and posturing, but sometimes one of us would get dragged off by the Old Bill. I got fined, then I got nicked for a more nasty punch-up. Nikki and I were serious by now, the fishing was taking over my life and I suddenly thought: Jamie, you can either carry on getting nicked – or sort yourself out.

So that’s what I did. I grew up a bit. I realised I was happy with Nik; I didn’t need to be getting pissed all the time and getting into rucks. If I’d carried on I’d have been banged up just like my old man and I didn’t want that.

Nikki was a catch, all right. She wasn’t tall, about 5ft 1in, with short, dark hair, and beautiful, deep eyes that melted me every time. She adored horses and had worked full-time at one of the racing stables in Newmarket before coming back to the island. Just like me, she was outdoorsy – she loved walking dogs – and, just like me, she didn’t give a damn. She wore jeans and jumpers, not dresses and frills; she was her own person, bubbly, feisty, and everyone else could sod off.

We really clicked. I could talk to her, tell her everything – moan to her about the bloody crew – and it just felt natural. I’d tell her about my battles with rival fishermen and the authorities and she completely got it. She was as much anti-establishment as I was but she was no pushover, either. If she thought I was wrong, she’d say so; if she wasn’t happy, I’d know.

Being with her kept me out of trouble, even slowed me down a bit until I started seeing things with a bit more perspective. I didn’t go off on one all the time, and I didn’t go out to get into trouble. Unless a mate was involved; if one ended up in a ruck, then we all did. Some things never changed.

It wasn’t long before Nikki and I moved into a little flat in Ryde together. By the time we got married she was six months pregnant and Maisy was born in 1989. I was working flat out with the fishing, building the boats and trying to earn as much as I could to support Nik and the little ’un. We had hard times, of course, but mainly good ones. It was all part of life; I was with someone I loved, I had my first kid and everything was all right.

Around 1995 we moved over to West Wight where my parents opened a fish shop to sell the catches we were bringing back. Trade was good and customers would often say, ‘Why don’t you open a restaurant as well? It’d be great to eat fresh fish here.’

Eventually, that’s what happened. Downstairs was the fish shop and upstairs got converted into the restaurant. The business was called Salty’s, which was my old man’s nickname, given to him by my sister – who insisted his goodnight kisses always tasted salty!

Our second daughter, Poppy, had now arrived and once we’d moved over to West Wight, Nikki started working in the shop. It wasn’t long before our son, Jesse, was born.

Throughout it all, Nikki never lost her love of horses. As our girls grew she spent a lot of time teaching them about ponies until it eventually became serious and Poppy ended up on the UK showjumping circuit until she was about 16. We had four ponies and they’d regularly go off competing.

That’s pretty much how it was – until our world suddenly capsized around us. Nikki had found a lump in her right breast and got referred to hospital, where she had a biopsy. I went with her that day and was still pretty much ignorant of where it was all heading. My Nikki’s indestructible. There were no anxious conversations between us. I genuinely thought everything would be fine. She was in no pain, we were laughing and smiling with life, the fishing was good and Poppy was having a great time with the ponies.

Indeed, I was out fishing when Nikki went back to the hospital with her mum for the biopsy results. I’d just gone round the Needles when I gave her a call to check all was good. ‘How’s it gone?’

There was a short silence that told me everything. Then Nikki’s voice, trying to be strong. Trying to be Stormin’ Norman. ‘It’s not good. He’s saying it’s alive, the tumour is active. They’ll have to go straight in and operate within two weeks.’

Oh.

‘Ok, look, I’ve just passed the Needles, I’ll be home soon.’

I put the phone down and steered the Galwad back into Yarmouth. Nikki’ll be all right.

She could have had the breast removed immediately, and maybe should have done. But it was nearly Christmas and she insisted: ‘I’ll get it done in January. I don’t want all this drama over Christmas and New Year. Let’s just enjoy ourselves.’

It wasn’t until a couple of weeks after the operation that we were told how long she had left to live. The results had come back and it was like being handed a sentence in court. In fact, I still wasn’t taking it in, even after I’d gone back to the oncologist and asked her to repeat what she’d said.

I was hearing words but they weren’t landing anywhere. Metastatic. That was one of the words. The cancer had gone metastatic.

Nik was still outside in the hospital foyer waiting for me. I was the one falling apart. I remember her saying, ‘If you don’t pull yourself together, Jamie, I won’t have the fuckin’ treatment.’

I was more angry and frustrated that something so evil had picked on her. Why the fuck did she get it when there were plenty of other bastards out there who drank and smoked all their lives yet got fuck all? That’s what I was really angry about. Why were the scumbags allowed to carry on living?

We decided to tell the kids as soon as we got home. Jesse was a young teenager by then and the two girls were a bit older. We sat them round the kitchen table and repeated what the oncologist had said. There were tears and hugs and then questions. I remember Jesse kept saying, ‘You’ll be all right, Mum, it’ll all be OK.’

Yeah, that’s right, Jesse. Mum’s Stormin’ Norman.

The girls were a bit more subdued. I think they had a better idea of what was in store. They realised. Nik, predictably, remained her usual self. She couldn’t stand people fussing over her, especially when they started asking, ‘Are you all right?’

‘Of course I’m all right, I’m here aren’t I?’