Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

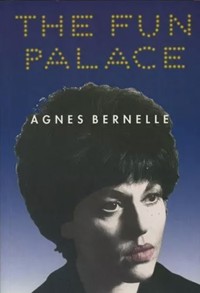

Agnes Bernelle, one of Ireland's best-loved stage performers, was born Agnes Bernauer in Berlin in 1923, the daughter of a renowned Jewish-Hungarian theatre impresario. In this sparkling, intimate memoir she recounts her early years in Germany, her family's flight to London after Hitler came to power, her anti-Nazi broadcasts to the land of her birth, her turbulent loves and family life and the blossoming of her career in film and theatre – from wartime refugee cabaret to the West End. In 1943 she married Irish Spitfire pilot Desmond Leslie, cousin to Winston Churchill, on the first day of peace. Inventive and resourceful, Agnes performed impromptu cabaret in Barcelona, befriended cat burglars, summered in Cannes and received the affections of, among others, Claus von Bulow and King Farouk. In 1956 she became the first 'non-stationary nude' in London theatre. Her original satirical cabaret, based around the work of Brecht and Weil, became the first solo show at Peter Cook's Establishment in Soho, and later had a three week run in the West End. In 1963 Agnes and Desmond moved finally to Ireland, where they found themselves facing into a troubled decade.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1996

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE FUN PALACE

An Autobiography

Agnes Bernelle

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

For my children, Seán, Mark and Antonia, and my grandchildren, Luke and Leah

Contents

FOREWORD

Agnes Bernelle claims to have been born in Berlin in 1923. Berlin one can believe: but seventy-three years old? Nonsense; she can’t be more than twenty-four, and a young twenty-four at that, a mischievous twenty-four. Enthusiastic, indefatigable, amorous, ambitious, loyal, resilient, funny, incredibly tolerant (except of intolerant people), forcefully feminist, instinctively rebellious, perennially skint yet imbued with ineradicable style, she emanates sheer Youth though every sentence in this book like a heron flashing its wings against a rainbow. But she must be the age she says, for she brings to us what seems a full century’s worth of inimitable anecdote: theatre, politics, social contretemps, the joys and miseries of an ‘open’ marriage, of life in Weimar Germany, Hitler’s Germany, England in World War II, the Riviera and (of course) Ireland. How many of us know how exiled German theatre-folk practised their art in London during the 1940s? Or have heard of the way young actresses were slotted into the war effort by the U.S. military? Or can guess what it was like to try to finance stage-shows and films in the post-war years of austerity? Agnes knows: she was there, and she did it. She met Marlene Dietrich when Marlene was a young mother making sandwiches in a Pimlico kitchen. She remembers her own mother escaping by the skin of her teeth from recruitment as a Nazi agent-provocateur. She tells how at the last minute she rejected a paradoxically indecent leotard for Salomé’s ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’, thereby becoming the first nude-in-motion on the censored British stage. In short, The Fun Palace is the widest-ranging, most instructive, most appealing theatrical/personal memoir one could possibly imagine, and it doesn’t even get past 1963. I want to read all about Agnes in Dublin (and elsewhere) since then: and so, I guess, will every one of her hundreds and hundreds of friends, in the ‘profession’ and out of it. Let’s hope there’s a second volume, soon.

JOHN ARDEN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My gratitude for help and/or encouragement is due to: Paschal Finnan, Jonathan Williams, John Arden, Crióse Brogan, Maurice Craig, Brendan Ward, Nuala O’Connor, Victor and Alma O’Reilly, Charlotte Bielenberg, Hans Christian Oeser, Ann Ingle, Lorraine Brennan, Barry Egan, my publisher Antony Farrell, Amanda Bell, Brendan Barrington, Bernard and Mary Loughlin and their staff at the Guthrie Center at Annaghmakerrig.

THE FUN PALACE

‘Everything is so dangerous that nothing is really frightening.’

GERTRUDE STEIN

I

It’s curious—but I never could remember leaving Berlin.

I can’t remember what time of day it was, or from which station we left—for surely we left from some railway station, one didn’t fly much in 1936—and did we take much luggage, and who came to see us off? How did we feel as we settled down in the railway compartment when the guard’s whistle made us into exiles with one sharp blast?

And yet I can recall almost everything else about that journey. The ship tossing and shaking us across the sea towards England, the immigration authorities at Harwich early next morning checking and rechecking our entry visas. My first English breakfast on my first English train. I can see it all even now, from the small glacé cherry on my first dining-car grapefruit, to the large sooty roof of Liverpool Street Station. I shall never forget arriving in London—but I never could remember leaving Berlin.

I was born there in 1923. My layette cost my parents several million Deutsch Mark, not because they were millionaires, though at that time they might well have been, but because I arrived in the middle of the Big Inflation, when banknotes issued in the morning weren’t worth the paper they were printed on by the afternoon, and my father, who owned and ran several theatres in Berlin, paid his employees in groceries collected at dawn from the city markets. It was an uneasy lull between world wars, marked by the collapse of the German Empire, the hasty establishment of the Weimar Republic, and the abortive Spartacist uprising.

Of course, I knew nothing about all that as I slept in my frilly cot in our apartment in Schöneberg, a residential district of Berlin much celebrated in song, which featured in one of my father’s musicals, Maytime.

We lived in a house overlooking the Viktoria Luise Platz—a small, pretty square which was not square at all, but round, and was, for a long time, the outside world for me. Unlike the private squares in English cities it had no railings, and was freely accessible to children less rich, and less protected, than I was. They swarmed all over it, playing hopscotch, cops and robbers and marbles. I envied them. I envied them their marbles in particular, and since I could afford to buy them rather than to win them from the other children, they became the currency by which I bought my way into their company.

We occupied only one floor of the house we lived in, which was not unusual then in Berlin. The residential houses were large and ornate, with massive entrance doors which, not like our own, were often flanked by caryatids, groaning under the weight of first-floor balconies. Our house had a lofty entrance hall with checkerboard marble tiles and a huge gilded mirror on each side. A long narrow corridor ran the length of the twelve rooms we occupied on the first floor. It was perfect for bicycling from my bedroom at one end to my playroom at the other. The bedrooms all had tiled stoves in the corners, which my parents had left standing, even though central heating had long since been installed.

The reception rooms could be made into one large continuous area by sliding their connecting doors into the wall, which was great for parties. The oval drawing-room had six tall windows, and after the many winter colds I caught during my over-heated childhood, my mother would muffle me up to my eyeballs, my hands in woollen mittens, my legs in itchy leggings, open all six windows wide, and take me for walks around the grand piano. I hated to be so mollycoddled and longed to be down in the square making snowmen with the local kids.

Apart from such minor irritations I think I was happy most of the time. I had been a late and much wanted child, and my parents could afford to deny me very little. Until I was three I had a pretty nurse called Ettie, whose cornflower-blue eyes regarded me with uncritical affection. I became used to being doted on, and to having my own way in everything. If I didn’t want to walk home from the park, I would sit on the pavement and howl. If I didn’t want my mother to go out in the evening, I would try to grab and tear her dress when she came to kiss me goodnight. If I didn’t want to eat my spinach, I would bring my fist down hard and make it fly all over the room, protesting loudly that I didn’t know right from wrong yet, and therefore should not be punished. In truth, I was a monster.

My parents had no option but to retire Ettie, who promptly replaced me with an illegitimate child of her own. They brought in a strict governess; she arrived in a green hat and was called Fräulein Basner. From the beginning I detested her.

One of my most vivid memories is of her first evening with us. Through two translucent glass panels in my bedroom door I could see the shadowy figure of Fräulein Basner unpacking her clothes and hanging them in a closet outside. I was standing up in my cot, howling for her to come back in and read me another story. She took absolutely no notice.

A picture of my older brother on his pony was hanging above my bed, and now whenever I come across it in an old photograph album I know again the awful frustration and rage I felt so many years ago when I turned my tear-stained face to it in noisy supplication. I don’t know if I really expected Emmerich to get off his horse and help me to attract Fräulein Basner’s attention, but she did not respond to my yells, and so began the taming of this particular shrew.

Although at the very beginning she was nearly dismissed for spanking me, Fräulein Basner stayed with us until I was too old to have a nanny. We soon became devoted to each other, and the formal ‘Fräulein Basner’ became the more affectionate ‘Bäschen’. When she left us, at the age of fifty, she would not look after any other children. Instead she advertised for a husband, and married a trombone player from the Potsdam Municipal Orchestra. We danced at her wedding, and lost touch with her when the war came.

In 1954, when I went back to Berlin for the first time, I got a message across to East Berlin where I had been told she was living. Returning late from a visit to the theatre, I found Bäschen sitting in the lounge of my hotel with a basket of eggs on her lap. She had been waiting there for many hours. How she got across that border I never found out. We had a tearful reunion, and I invited her for a proper meal, but she had to get ‘across’ before midnight, and only took the time to tidy my room in the hotel before she left. I never saw her again.

Christmas was always a great event in my parents’ house. All our extended family and many of our friends would come for dinner.

A tall tree was put up in the drawing-room, with real candles and a great deal of angel hair (lametta) hanging from its branches in long swathes of silver. Around the room were small tables stacked with presents for everyone and on every table was a plate of goodies: nuts, raisins, honey cake and marzipan.

I was usually too excited to sit obediently through Christmas dinner, which we had on Christmas Eve, as is the custom in Central Europe. We had carp with parsley sauce, or goose with chestnut stuffing, and a sweet made of poppy seeds—which I hated. After the grown-ups’ coffee and brandy, the long-awaited moment came at last. My mother disappeared behind the double doors, which had hidden the drawing-room all day, and the sounds of ‘Stille Nacht’ came wafting through from our hand-cranked gramophone. The doors opened slowly and we rushed in to find our presents.

One particular Christmas I made straight for the tree, for underneath its branches I could see a wondrous object: a miniature Citroën complete with headlamps, indicator, number-plates and fat rubber tyres. I jumped into it and grabbed the steering wheel. In vain I looked for the ignition key.

‘How do you start the engine?’ I asked anxiously.

‘You don’t, Mädichen,’ said Uncle Carl Meinhard, whose present it was. ‘You have to pedal it.’

Pedal! I had to pedal it!!! I didn’t even try.

My parents were embarrassed. Carl Meinhard was my father’s partner, and a very generous man. He had had this tiny Mercedes specially built for me in the Citroën factory, a replica of their latest model, no less.

‘Aren’t you going to say thank you to Uncle Carl?’

I hesitated for only a moment, then went to my table, took a marzipan orange and handed it to Uncle Carl.

‘Thank you,’ I said in measured tones.

‘Well thank you, my dear,’ said Uncle Carl, ‘but look here, this isn’t a real orange.’

‘It isn’t a real car either,’ I replied.

I am told I would never play with it, and eventually it was given away.

When I was five, my parents put me into a small Montessori school in the Palais Goldsmith-Rothschild on Unter Den Linden. This school had been started privately by the Baroness Rothschild to prevent her children from having to go to ‘common’ schools, and coming into contact with ‘common’ germs. Her family paediatrician, who was also ours, had selected a small group of sufficiently ‘germ-free’ tots of whom I was one, which suited my doting parents.

Each morning I was driven to school in a black limousine by a chauffeur in a smart, buttoned tunic, knee-breeches and a peaked cap. I fondly believed that the car belonged to my father, whereas it really was the property of the chauffeur. This was no affectation on my father’s part. He needed a car and a driver in his busy life, but owning a car privately was not yet in fashion in Berlin in the twenties.

In the Montessori school I quickly learnt to read and write. The method is good, provided the school is consistent in its application. After one year my mother came to check on my progress. She found to her dismay that we, the original pupils, were being left more or less to our own devices, abandoned in favour of a new ‘germ-free’ class. This was not strictly the teacher’s fault since the school was required by law to take in new children every year. The problem was that there was just the one teacher. ‘Mann kann nicht mit einem Toches auf zwei Hochzeiten tanzen (Don’t try and dance at two weddings if you have only one bum)’ remarked my mother, who was always strong on proverbial wisdom, and as I was not receiving instruction she removed me from the school.

On my first day at home, I was upset and worried because I did not want to go to a bigger school. Not even the arrival of my father’s barber, Herr Kyrieleis, could placate me. He usually managed to thrill me by moving his ancient razor up and down a leather strop as a prelude to covering my father’s face with an excess of soapy lather, but on that day I could not be consoled by such trifles.

Bäschen produced a volume of Hauff’s Märchen to cheer me up. Cheer me up indeed. There was no question that these tales were meant for children, but they were horrendously violent. The Struwwelpeter, a favourite with German children, was bad enough, but to play the flute on the bones of one’s murdered brother or to have one’s head hammered to the mast of a sinking ship with a rusty nail—this did not seem to me to be a suitable literary diet for a child. I called for an eraser and spent the morning rubbing out the words of each offending story until hardly any print was left. After that I felt better and began to think more positively about the ‘other’ school.

The ‘other’ school, though it accepted children of all denominations, was run by a Jewish lady, Fraülein Zikkel, and was certainly regarded as Jewish by the Nazis, who later closed it down.

Sending me there, a Protestant, continued a family tradition of religious reversals. A generation earlier, my Jewish father had attended a Benedictine school in his native Budapest. There was no better school in all Hungary, and my grandmother decided that only the best was good enough for her little Rudie. I don’t know what strings she had to pull, or what charms she brought to bear upon the holy monks, but her little Rudie was accepted, the only Jewish boy in the entire school. Of course, at first he was taunted by the other boys, but my grandmother was a resolute woman. On the first occasion that presented itself—a nature walk—she whacked one or two of them with an umbrella and settled the matter once and for all. There was never any trouble after that. My father fitted into monastic life and was often found on his knees before the holy shrine, serving mass along with the other altar boys.

This kind of ecumenism has been the hallmark of my family. My earliest religious affiliation was to Martin Luther. Someone had given me a picture of him, double chins and all, and I stuck him to my bedroom wall and gazed at him adoringly for years to satisfy my inborn need for an idol.

In any case, my parents would have found it hard to give me meaningful religious instruction.

My Jewish father’s child by his Catholic wife is a Protestant; and while I, his child by his second, Lutheran, wife, eventually became a Catholic, I suspect that if I had not been brought up a Protestant I would have become one sooner or later. This state of affairs has never particularly bothered any of us, and I can’t help feeling that God, whatever religion He is, must prefer it to sectarian strife.

My formal education was not extensive. I never went to university, alas, but because I have lived in several different countries, held different nationalities, and been involved with several different religions, I have been loyal to the communities I have lived in and the associations I have joined. Thus I may be forgiven for refusing to feel German, though I was born in Germany; or Hungarian, though my father came from Hungary; or English, though I was brought up in England; or Irish, though I am living in Ireland now. Nor do I count myself as ‘Aryan’, like my mother, or Jewish, like my father, nor even a ‘good Catholic’, though our cook tried her best to make me into one.

My mother, Emmy, was born in 1887 in Wittenberge, which lies on the railway line between Hamburg and Berlin—as she would always emphasize, because she was the daughter of a railwayman. One of five children, my mother was pretty and ambitious. By the time she was twenty she had decided that life in a small provincial town was not for her. At that same moment, my father, who was seven years her elder, was negotiating the purchase of his second theatre in Berlin. It seemed unlikely that they should ever meet.

My grandparents did not approve when my mother left for Berlin. For a young girl to take such a step was unheard-of in those days. What would the neighbours say? Emmy arrived in the big city with one small bag, wearing the smart new outfit she had made herself. It did not take her long to find a position. The Bernauers were looking for a nanny for their son, and in that responsible but lowly position, my mother entered my father’s household.

She always tried to hide this fact in later years. When my father wrote his memoirs at the end of his life, she made him take out any references to their original relationship. I have always thought the story touching and romantic, and hope that wherever she is now she will forgive me for revealing it here.

My half-brother, Emmerich, was only three years old when his mother was struck down with typhus at the age of twenty-seven. She caught the disease on a second honeymoon in Spain. On her deathbed she called for Emmy. ‘Promise me,’ she whispered, ‘that whatever happens you will never leave my child.’ My mother, who was holding little Emmerich in her arms and weeping, vowed to bring him up as her own.

Not long after Henny Remilly’s tragic death, my grandfather, who considered his daughter’s presence in the house of a widower unseemly, demanded her return. Emmy arrived in Wittenberge and true to her promise had Emmerich in tow. What indeed did the neighbours say—returned from the city in disgrace with an illegitimate child? My grandparents must have been relieved when Emmy took the boy back to Berlin.

It was then that she took control of my father’s household. Calmly and efficiently she executed all the duties of a wife bar one. Pretty as she was, my father did not then regard her in any romantic way. Freed from the bonds of a too-early marriage, he threw himself into a bachelor’s life with gusto. Ladies came and went. Actresses and other beautiful women frequented his parties and, more often than not, his bed. My mother loved him secretly for many years.

When Emmerich was old enough, Emmy became engaged to an old admirer, a Berlin lawyer named Paul Nordmann, who had been waiting patiently for many years. She gave in her notice to my father. To her dismay he did not make a comment. A week went by. One morning she saw a familiar overcoat hanging in the hall and heard male voices in the study; presently she was called inside.

‘I thought I had been invited to Berlin to talk about your marriage to Paul Nordmann,’ said her father, ‘and now I am told that you are marrying Direktor Bernauer. He has just asked me for your hand’.

They had a fairy-tale wedding, and went on a fairy-tale honeymoon—my brother went as well—then came home to Viktoria-Luise-Platz to live happily ever after. But did they? Poor Emmy, not for long did she enjoy the ‘good life’ with her Rudolf for which she had waited so patiently. Her prince, though charming, was also a Jew, and in the beer gardens of Munich a man called Adolf Hitler was beginning to make his name.

My father had barely reached his teens when his parents decided to leave Budapest and move to Berlin. He waved goodbye to the holy monks and entered the Friedrich Gymnasium, where he learnt to speak and write flawless German. At university he studied philosophy and history of art, and because there was little money at home, he took a part-time job selling Meyers Konversations Lexikon—the German equivalent of Encyclopaedia Britannica—from door to door. At night he penned lyrics for the satirical cabarets, which were flourishing at the turn of the century in Berlin. These verses were set to music and later published in a collection called Lieder eines bösen Buben—Songs of a Bad Boy—from which I draw material for my shows and records to this day.

When after a year my father had failed spectacularly to sell a single set of encyclopaedias, he threw in his hand. Deeply embarrassed, he first bought a set for himself, so he could report at least one customer to his employers. This set was destined to travel across Europe and has come to rest on my bookshelves in Dublin.

My father, much influenced by the poetry of Heinrich Heine, also wrote lyrical verses in his youth. Grandfather Joseph surreptitiously sent his early poems to a literary magazine and was, if anything, more thrilled than his son when they were printed.

Joseph Bernauer emerges from my father’s descriptions as a gentle and caring man and does not appear suitably cast for his role as a sales representative. Not long after his forty-fifth birthday, he fell off his bicycle and injured his liver. A year later he lay dying of cancer. This was the end of father’s dreams of an academic career—he left the university of Berlin to provide for his mother and younger sister Gisela.

Attracted to the theatre from his student days, when he took part in crowd scenes, he decided to go on the stage. It seems almost unbelievable that a theatrical career was ever considered a safe way of earning a living, but the system of theatre in continental Europe made this enviable assumption quite natural. There were, and are even today, many steady jobs for performers, directors and designers in Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Every provincial town has its state theatre, most of them with artists on long-term contracts.

Whenever I think of the fate that forced us to emigrate from Berlin, it is not the country I regret leaving, or the possessions we had to abandon, but always the loss of this theatrical system, which was originally my birthright, and which might have provided me with a far more comfortable and rewarding career had I been able to stay there. After all, my parents had christened me ‘Agnes’—Agnes Bernauer, after a classical play by Friedrich Hebbel—in the reasonable assumption that one day it would say on a German playbill ‘AgnesBernauer, played by Agnes Bernauer’.

As an actor my lucky father first worked for the great Otto Brahm at the Deutsches Theatre in Berlin. There he made friends with Carl Meinhard. In 1901, when they were barely in their twenties, they put together a light-hearted entertainment which could be performed on special occasions in the homes of well-to-do members of the German bourgeoisie. They gathered together a small, but talented, company, ‘the Bad Boys’, and when they found that there was no suitable material available they wrote their own songs and sketches. My father invited Dr Wulff, the editor of Lustige Blätter, the German equivalent of Punch, to contribute some humorous pieces and to issue invitations for the try-out. His reputation would ensure a good attendance. And so it did, but in a most unexpected way. Instead of the bankers, factory owners and businessmen the Bad Boys had planned for, Dr Wulff had invited the entire artistic and cultural élite of Berlin, in the hope of showing off his own masterpieces—which turned out to be so bad that most of them had to be cut during rehearsals. The Bad Boys and their actors and actresses were thrown into a panic. They were only too well aware that failure on this night could mean the end of their careers, since everyone who could give them work was right there to witness it.

They need not have worried. That night saw the birth of a new style of cabaret entertainment—an hilarious satire of the German artistic and literary world. This required an eagle eye, a sensitive ear, a razor-sharp wit and above all an audience intelligent and informed enough to understand all the allusions. In his ambitious recklessness, Dr Wulff had provided the Bad Boys with just such an audience. The reception was tumultuous. The original plans for the show were soon abandoned. Since neither Meinhard nor Bernauer wanted to give up a serious career in the theatre, they held their Bad Boys evenings only once a year, at midnight, for invited guests.

These guests could be separated into three categories: those who would telephone before the show to ask if it was perhaps their ‘turn’ to be parodied; those who delighted in the distorted image of themselves presented on stage by the mischievous company; and those who wrote offended letters, asking if they were of so little importance that the Bad Boys had not found them worth holding up to ridicule.

The Bad Boys continued to prosper and my father became an actor in Max Reinhard’s Ensemble at the Berliner Theater, which seemed to fulfil his ambitions at the time. As a director he was not ‘called’, but ‘chosen’. Meinhard, always the entrepreneur, had gathered together some stars of the Berlin stage to send on tour during the silly season. They were waiting for a famous director to arrive from Vienna. In the meantime Meinhard asked his buddy, my father, to sit in at rehearsals for a few extra marks and to provide a focal point for the orphaned company until the great man could take over.

A short time into the first rehearsal the leading man stopped in front of my father. ‘You don’t like what I’m doing!’ he said. ‘No—I mean yes, of course I do,’ stuttered my father. ‘No, you don’t. I can tell by your face. I wish you’d tell me how you would have me play this scene.’ My father was mortified, but this was only the first of many such interruptions. The company would stop, whenever my father put on one of his faces, to take advice and direction from him. By the end of the week they refused to work under the famous man from Vienna, and by the end of rehearsals my father had become their official director.

In 1908 Carl Meinhard and my father rented the Berliner Theater and set out on a long and fruitful partnership in theatre management. Over the next ten years they bought the Komödienhaus, the Hebbel Theater and the Theater am Nollendorf Platz, which they managed, putting on plays ranging from classical drama to light-hearted farce. With so many theatres to finance they needed a great deal of money, and since there were then no grants or subsidies, my father hit on the idea of writing and producing his own musicals. This would keep the cash ‘in the family’, and instead of paying out royalties to other authors, he could use the money to subsidize two of their theatres which showed only serious drama. Thus Maytime, The Chocolate Soldier, The Girl on theFilm and countless other operettas were born, while the theatres given over to classics and serious modern plays went from strength to strength under father’s direction.

The Meinhard/Bernauer venture closed down in the year I was born. They leased their theatres to other people and dissolved their partnership. Father was then only in his forties, but considered that he had worked long and hard enough in the theatre. After all, he had started in management exceptionally young. He used to frighten me, and I suspect he frightened my brother before me, with the assertion that no one who had not ‘made it’ by the time they were twenty-three, would ever come to anything. I know he died, when I was thirty, with the firm conviction that I was, and would always be, a hopeless failure.

My father brought me up to be a gentleman. He could not help it, of course, since he himself was one of nature’s gentlemen. His word was his bond, and he rarely had to sign a contract in all his long years running his theatres. He was the biggest single influence in my life. He often told me he had no regard for family ties and that he loved me not because I was his daughter but because I was his friend. If I misbehaved he sent me little notes telling me how much his ‘friend’ had disappointed him. I have been told by analysts that this put a strain on me but neither of us was aware of this danger at the time and I adored him without reservation, and would do anything to live up to his concept of me as another son. He consulted me at an early age on matters concerning his work and allowed me to sit in on script conferences. Construction and storyline were all-important in those days, and I have never quite rid myself of the urge to reconstruct a script—anyone’s script—that seemed to me to be too shapeless or too long.

A dedicated movie fan from the age of five, I knew the titles and the casts of every German film in the twenties and early thirties. After his retirement, when my father began directing ‘talkies’ in Berlin, he would not only ask me for my casting suggestions but would often act on them. Film stars who appeared in father’s films could not have known that they had been chosen by a nine-year-old.

Father never lost his academic bent, even though he had not finished his university courses. An afternoon with him in the Pergamon Museum was an experience to be treasured, but best of all were the morning sessions in his dressing-room. He had lost most of his hair at an early age. Being vain, he grew his side hair to a special length and slowly and carefully plastered it, strand by strand, across the top of his head until it formed a shiny dome. Whom he wanted to fool that way I do not know. I think he did it just to please himself, and it certainly pleased me, for it prolonged our magic mornings, when he taught me more than I would ever learn at school.

He was a very honest man, but at times he took his honesty to ridiculous lengths. Fleeing from the Nazis, he would not cheat them by smuggling out some of his cash, and went to London with nothing but his gold watch to pawn. He was also a very human man with human foibles. His biggest weaknesses were cards and women. He loved to play cards in Berlin’s theatre club until the early hours of the morning. Not until I was almost grown up did I begin to understand some of the odd results of this obsession. Those little blue stickers, for example, that would drop to the ground from beneath our chairs and tables at certain times: if this happened on some hot summer afternoon when my mother was entertaining friends, she would turn pale and hastily place a foot on them. I must have been the only person present who did not know that these pretty little tabs came from the bailiff and had to stay until my father’s gambling debts were paid. He must have always paid them, for no one ever came to cart our furniture away, at least not until we had to sell it during the Nazi era.

Against all my expectations, the ‘other school’, which I had dreaded so much, was a great success. I enjoyed the more challenging way we had to work there and learnt to socialize with other children, which was wonderful, because I was, technically, an only child. Brother Emmerich was seventeen when I was born and within a few years he would go to work and later marry Edith, whom he met when they were both fifteen.

Emmerich joined the Ullstein Group as a journalist, and as such he broke new ground. If he was asked to do a report on brewing he would get a job in a brewery. If he was asked to write about the building trade, he would become a labourer on a building site. It was always exciting to wait for him to come home in the evening in dirty overalls, and it was thrilling to be allowed to stay up late and celebrate when he became editor of the Vossische Zeitung—at the age of twenty-three! It was even more gratifying when father gave him a telling-off for refusing to cut his toenails. But none of this could keep me entertained for long and until I went to the new school I had to find my own amusement.

I spent many hours dressing up. My mother had the most exquisite beaded gowns. Her youngest sister Martha, for whom she had found a job as a seamstress with one of her own couturiers, Gerson Prager Hausdorff, one of Berlin’s grandest fashion houses, had ended up marrying the son and heir.

Both sisters now got their clothes at knock-down prices, and after they had worn them a few times in public I was allowed to play with them. Dressed up like that I would stand in front of the tall mirror in my mother’s sitting-room, play my little gramophone, and pretend I was the singer on the discs. I sang along with the recorded voices of pop singers and opera stars alike. Did I say ‘pretend’? I was all of them.

I also had a splendid tent, hand-painted with galloping horses and Indian braves. Since we had no garden, I put it up indoors and retreated into it with a pile of cushions and an even bigger pile of books. When I had raced through my own books I would go into my father’s study and borrow his. My mother always smiled approvingly when she caught me disappearing into my tent with finely bound volumes of Dickens or Tagore, and I doubt if she realized that the edition of the Arabian Nights she brought to my bed when I had the measles was not the children’s classic she had read but the unexpurgated version.

This was not the only erotica in our house. Illustrated copies of the amorous adventures of both Casanova and Don Juan were hidden away where I could easily find them, providing me with a liberal and most imaginative sex education, which I shared generously with my friends. When Bäschen was busy somewhere else, they would join me underneath my bed, armed with torches, to leaf excitedly through the forbidden pages.

Of course there were more innocent pleasures to be had. My very best friend Vera Calmann—one of a long line of Veras in my life—lived in a flat above the Scala, the great variety theatre of Berlin. Vera’s father was manager, so we children had the run of the place. We could plonk ourselves down in the front row and watch the programme as often and as long as we pleased. We saw some of the finest international variety acts over and over again. My favourite by far was the girl in the sky-blue satin shorts, who sidled coyly across the stage between acts, carrying a numbered card and wearing a fixed and manic smile. I dreamt of growing up to be just like her.

The conductor of the Scala was a matinée idol, the suave and handsome Otto Stenzel. Poor Vera had to sit through endless shows with me so I could ogle at gorgeous Otto and his Brylcreemed hair. I am sure I am not the only one of my generation who recalls it all with such nostalgia—the Scala, Otto Stenzel and the ‘Number Girl’. How sad I was, when the war was over, to find them gone. The Scala had received a direct hit and I could find no trace of it.

My parents took me to plays and operas from an early age. The most lavish production I saw was Verdi’s Aida in the open air, on an Italian beach. The vast sandy strand was a perfect setting for the story, played out against a midnight sky. There were real elephants on the stage.

I spent the next few years entertaining my parents’ dinner guests with a parody of Aida’s famous aria in Act One, which I decided was much too long and repetitious. Wrapped in my mother’s chiffon scarves, I would wring my hands, which were covered with her rings, and roll my eyes to heaven. ‘O Patria Mia,’ I would warble, ‘non ti vederai piu—non piu ti vederai, patria mia …’ until I was snatched up by Bäschen and carried off to bed.

I was forever acting and dressing up, and wanted to try my hand at production. Beginning modestly, I staged Lebende Bilder—living pictures, picking my ‘cast’ from amongst my schoolmates, and we put on a show for my ninth birthday. The sliding doors between our two drawing-rooms opened to reveal scenes of well-known fairy-tales: ‘Sleeping Beauty’, ‘Mother Goose’, ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’. I appeared as Snow White with seven of my dolls dressed up as dwarves.

My next attempt was more public. I was ten years old and now in the Rückert Lyceum, a high school for girls. On a day in mid-summer, the school hired a barge to take us all out on one of the many waterways that surround Berlin. We would stop for lunch in one of the secluded waterside inns and enjoy the entertainment laid on by the senior forms. I did not see why the juniors should not make a contribution. I found a verse play in a children’s annual that seemed suitable. It was about one Abu Hassan, a jolly rogue, who, together with his wife decides to con his sultan and sultana. Weeping profusely and making ‘much ado’, they go to the palace and each in turn claims that the other has ‘expired’, pocketing a handsome purse every time. A dilemma arises when both sovereigns arrive at their humble abode to find out which of them is dead.

I dressed my actors in my mother’s Gerson Prager Hausdorff glad rags, and the sultan and sultana in particular were a splendid sight. There was no curtain at the inn, which I had failed to foresee, and when my actors, playing dead, arose to make room for the next scene, they had to drag their shrouds behind them. This made the play more hilarious than even I had anticipated. My success at that time was chiefly accidental, and I could not have foreseen the effect it was to have years later on my professional career.

In 1978, when I wanted the rights for Günter Grass’s stage play Onkel Onkel for my first attempt as director at the Project Arts Centre in Dublin, I wrote to Kiepenheuer, Grass’s publisher in Berlin. Would they consider me, an untried director, worthy of this privilege? Imagine my surprise when I received permission almost by return of post. The head of the publishing house, Dr Maria Sommer, wrote asking me if ‘Agnes Bernelle’ could be ‘Agnes Bernauer’, her erstwhile fellow pupil in Berlin, whose production of ‘Abu Hassan’ had given her so much pleasure during a school outing that she had chosen theatre publishing for her own career.

In 1930, when Joe May directed a film called Eine TolleBallnacht for UFA, the biggest German film company, he needed a little boy. When he did not find what he was looking for, he rang my father and asked if I could play the part. I was to wear a sailor suit. My hair was fairly short with the then-fashionable fringe and Uncle Joe said it would have to do. I was thrilled and felt that now at last I was a true professional. My one and only scene was with a well-known German comic, Jacob Tiedke, who was the butler. The unfortunate young woman who played my nanny could not act and so the scene was re-shot with a more experienced actress and I had two days of filming instead of one.

UFA invited me to the première of the film. There was a seduction scene in it, played between Robert Thoeren and my ‘screen mother’, Nora Gregor, on a couch. Compared to sex scenes in today’s cinema, it must have been extremely tame, but when it appeared on screen, my mother told me to cover my eyes. I did so obediently but was nevertheless aware of what was going on. After the screening we were all asked to go on stage to take our bows and were given large laurel wreaths with satin sashes, our names marked on them in golden letters. It was a German custom on opening nights.

Not long after my film début, Paramount in Paris wanted a ‘boy’ just like me, with a sailor suit and a fringe. They offered a five-year contract which my father turned down. ‘If you want to be an actress later on,’ he told me, ‘you will benefit from growing up in a normal way.’ I cried for days. I often wonder if my father would have acted the same way if he had realized how close the Nazis were and how slim my chances were of growing up in a ‘normal way’.

II

It was always an enormous thrill when my maternal Grandfather Erb came on a visit to Berlin. He had a long bushy beard and when he came to pick me up from school the children took him for Father Christmas. On the rare occasions when Bäschen went to visit her mother in Koenigsberg I was allowed to stay with him and Grandma in Wittenberge. I loved their little house with the dark, narrow stairs, the heavy Germanic furniture with the white doilies on the arms of the chairs, the grandfather clock in the corner and the Victorian children’s books on the shelves; I loved their breakfast of sausages and cheese, eaten from small wooden boards in the shape of pigs. I loved going upstairs to Aunt Bertha’s flat to eat the caramel sweets she made for me. I even loved the small enamel bowl on the old washstand that had to be filled by hand for my morning ablutions. And most of all I loved cycling through the little town with my cousin Rudie, something only big children were allowed to do in Berlin.

Once my grandfather took us to a fun-fair on a large meadow outside the town. I had never been to such a place before and found it enchanting. There were dodgems, coconut shies, shooting galleries, roundabouts and even a bearded lady, but most delightful of all was the Fun Palace, an extraordinary building, the like of which I have never encountered since.

First you had to go up what was called a ‘shimmy stair’, a wooden stairway divided down the middle. As you set your foot upon it the two halves began to move in opposite directions, one up and the other down. It took a while to get up this busy staircase; giggling and panting you finally arrived on a wooden walkway which ran around the little building like a balcony. Lulled into the false belief that all you had to do now was walk along it to get to the other end, you soon found yourself stumbling, falling and crying out in surprise, as the planks collapsed beneath your feet and flicked you up and down. Other lengths of flooring were even more slyly deceptive. You expected them to move, but they failed to do so and just when you were sure you had nothing more to fear they gave a sudden heave and tilted you on the floor. On finishing the course you entered a small chamber containing a single seat constructed like a garden bench; instead of wooden slats it was made of metal rollers. As soon as the door shut, leaving you in the pitch-dark, the metal rollers began to roll. It is impossible to describe the sensation. It was as if the earth was moving away from under you. Without even time to scream, I found myself sliding down a huge chute, made, I believe, of canvas, with people before and behind me. This was delightful and quite the best part of it all. I wished I would never reach the bottom, but reach it I did, to be collected by Grandfather and taken home for tea.

I have never forgotten the Fun Palace, because all my life I have been subtly reminded of it. Perhaps I have just about arrived at the top of the chute. Going down will be exhilarating and rewarding, I feel, but I hope I shall not get to the bottom too quickly and too soon—and will there be an old gentleman with a white beard awaiting me?

When I was nine years old, my grandfather travelled to the Rhineland and the Schwarzwald region to visit the towns and villages of his youth. His ancestors had crossed the Rhine from France during the persecution of the Huguenots by Louis XIV. Grandfather was born in Karlsruhe, but moved around a great deal because he was a railway carpenter. He met Grandmother during a time up north and settled with her in Wittenberge. He had never been back to his birthplace, and now he wanted to see it once more. He must have had a premonition. My mother, brother, sister-in-law and I went with him to visit some of his remaining relatives in Pforzheim and Karlsruhe, and later spent a few weeks holidaying in Glashütte, a small village at the edge of the Black Forest.

I had a great time that summer, especially in Glashütte, where I made friends with the children of local farmers and was allowed to take part in the haymaking and its attendant jollities. I also rallied the other children who were staying in the only village inn and founded a ‘literary club’. This involved the compulsory wearing of pale-blue ribbons and equally compulsory meetings in a shed to listen to me reading excerpts from my ‘works’—romantic novels I had taken to writing around that time. I must have been an insufferable bully, since I cannot imagine that any of those unfortunate children enjoyed wasting their precious holiday time on such rubbish. My playmates, the boys in particular, went on strike about wearing my ribbons, but none of them ganged up to throw me into the village pond.

All these activities came to a sudden end when Grandfather suffered a stroke. He had always been healthy and hearty, and only days before we arrived in Glashütte he had walked to the top of the Feldberg, a fairly steep ascent. ‘I should never have let him do it,’ wept my distraught mother. I was taken into a darkened room to say goodbye to him. He was as white as the sheet he lay on, and made horrible rattling noises as he gasped for breath. He was gone before the morning. It was my first encounter with death.

After Grandfather’s funeral in Wittenberge, I retreated more and more to my favourite place, our balcony at Viktoria Luise Platz, and spent a great deal of my solitary leisure time there.

From this balcony I watched with awe as the great airship Zeppelin, followed closely by the bulkier Hindenburg, flew over Berlin. On this balcony an older playmate told me about bombs, a new and alien concept to my world. The thought that human beings could aim such horrifying instruments of death and mutilation at others, that they could drop these obscenities on sleeping cities, was chilling to me even then. I have never been able to divorce the concept or the reality of bombs from the memory of this moment on my beloved balcony. It is an irony of fate that in the war that followed it was that sturdy structure and not this more fragile being which was destroyed by bombs.

It was from this balcony also that I watched the long columns of voters setting off to put Hitler into power and I spent many hours grieving there, not only for my Grandfather Erb, but also for my Uncle Berzi Gonda, who died of a sudden heart attack when I was ten. Who would bring me yellow feathers for my dolls from his factory now? Who would give me a banana every time we met? Had I but known it, his early death saved my favourite uncle from untold suffering. His wife, Aunt Gisela, and one of his daughters ended up in Belsen. My aunt, a spirited woman, remarried there, but both she and her new husband perished. My cousin Ilma miraculously survived five years of suffering, and just before the end of the war, when she and other living corpses were about to be driven into a Polish lake, she heard gunfire and saw the camp guards jumping from the train. American soldiers came out of the bushes and liberated the prisoners just in time.

Whereas my Jewish relatives on my father’s side were either killed or tortured in the camps, members of my mother’s ‘Aryan’ family married men in Nazi uniform. I think my mother had expected more sympathy from her family for her Jewish husband, who had always been there to help her brothers and sisters educate their children and to take them travelling abroad. After the war she quickly forgave them and spent a great deal of time sending food parcels to those of her family who had survived. Alas, there weren’t all that many. My favourite cousin Rudie had fallen during the last week of the war; brown-shirted Ernst Weise was killed long before; my Uncle Franz, Rudie’s father, who had escaped the draft because of his age, was taken to Russia and put to work in a factory; he never returned. My mother’s family, more fortunate than my father’s during Hitler’s time, paid dearly for their privileges afterwards.

When my father retired he bought a villa in a place called Abbazia in Istria, which was then part of Italy. Until 1933 we spent several months there every summer. Our journey to Abbazia from Berlin each year came very close to resembling a royal progress. Our party usually consisted of my parents, myself, my nanny, my brother, his girlfriend Edith, assorted female cousins who were brought along to find rich husbands on the Riviera di Levante, our cook, three cats, the luggage and my hand-cranked gramophone. Those members of my family who were not travelling came to see us off at the station, bearing gifts.

Once when the train broke down after puffing and panting over the Brenner Pass, our party got out onto the small platform of a mountain halt, wound up my gramophone, and started a merry dance in which most of the other passengers joined.

I vividly remember watching from the wide luggage net, above the seats, into which I had climbed. I always spent the best part of any journey in one of those nets, and refused to come down until we arrived at the tiny station above Abbazia where we would be met by the local taxi and whisked downhill to our house.

Originally Abbazia—renamed Opatia when it became part of Tito’s Yugoslavia—was an Austrian possession, much loved and frequented by the imperial court of the Hapsburgs. Claimed by Italy at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, it now sported the flags and emblems of Mussolini, but its spirit of gaiety and opulence was largely unchanged and many members of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy had managed to hold onto their villas. My father, though respected at home as an artist and impresario, must have been a parvenu by their standards, but he was graciously accepted once he became the owner of the charming Villa Belvedere, so called because of its wonderful view across the bay of Istria.

My first call upon arriving was always to the garden, a sweet-smelling Eden bursting with delicately scented shrubs and flowers. I would climb high up into our fig tree and pretend I was Jane of Tarzan fame.

I know, of course, that we are given to idealizing the past. ‘The good old days’ we all remember so well were often nothing of the kind, but Abbazia really was a dream! Tall palm trees lining every path and exotic blooms everywhere.

A picture in an album shows me howling in the water, but I learnt to swim happily enough a few years later in the silken Adriatic sea. And what a thrill it was the first time my instructor took me ‘off the hook’ and I discovered I was swimming on my own.

Each day we walked through the small resort to the Lido, a specially imported sandy beach, which had been cleverly laid out between the rocks. The way down to it led through a little park where a band used to play. While I gathered the pistachio nuts that had fallen on the path, munched ‘caramelli mandoli’ (sugar-coated walnuts on a stick), Bäschen fell in love with, and became engaged to, the leader of the band. After that I could hear her every morning doing slimming exercises in her room.

Poor Bäschen—all that noisy huffing and puffing may have helped her to lose weight, but it did not, after all, get her to the altar. Her Italian lover died of flu the following year. I don’t remember sharing in her grief. Selfishly I was too glad she would not be leaving me.

When my brother was twenty-one, my parents gave a ball for him at Villa Belvedere. Almost ill with excitement, I watched the preparations being made. Small as I was, I did my best to help out in the garden. I swept the marble dance floor, supervised the Chinese lanterns, helped to decorate the tables set out on the lawn, and fussed around the specially installed bandstand.

At six o’clock they said I should go to bed and have a nap. I didn’t want to miss a moment, but they assured me that no guests would come till after dark.

‘And you will wake me up at midnight Bäschen, promise?’

‘Of course, of course—now go to bed.’

When I awoke the sun was up. The last guest had left hours before. The debris of the ball was all over the garden. I did not help with the clearing up.

Villa Belvedere was usually filled with summer guests. My father, who loved writing plays but hated writing them alone, always had one or other of his co-authors to visit. My mother invited her family, all of whom brought me toys: a garden swing, a huge teddy bear on whose lap I could sit in my rocking chair, a wooden cannon with exploding shells which I could train on unsuspecting guests—but none of these possessions could outdo the Christmas orange I was given once in Abbazia.

My favourite among my summer friends was Tutzi, orphan grandchild of the verger of the little church that stood next door to our house. She would come across in her faded cotton dress to play with me, and I would listen eagerly for the soft patter of her bare feet outside my veranda. One year I was getting over a tonsil operation rather slowly and my parents felt that the warmth of an Italian winter would do me good. I looked forward to Christmas with Tutzi. It would not be quite as grand as usual—none of the family were with us—and the house, the tree, and everything would be a little smaller, but there should still be enough glamour left to dazzle her. But Tutzi had no time to come. There was a great deal to be done over Christmas in the little Protestant church and Tutzi had to lend a hand. She worked from early morning until late at night and I hardly saw her.

To make up for it she had me invited to the special children’s service a few days after Christmas. Full of suppressed excitement I presented myself at the parsonage door and was taken into the church by a well-scrubbed Tutzi in her Sunday best. I had never seen her wearing shoes before! We sat down at the back of the church, sang Christmas carols in Italian, and listened to the words of the gospel: ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me …’. After the sermon all the children were asked to come up to the front, one by one. The pastor had a large basket by his side which was brimming with golden oranges. Each child was told to take one—even me. As I tiptoed back to our pew I thought my heart would burst. I held my precious present tightly in my hand. It made me feel I really did belong.