7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Maddy's husband, the poet Michael Donaghy, died suddenly at the age of fifty, leaving her to bring up their young son alone. After the shock of his unexpected death, the funeral and public mourning of this well-loved and respected writer, Maddy had to help her son deal with the loss of his father and come to terms herself with being a lone parent. In this extraordinary account, she describes how grief and bereavement had re-opened the wounds of her past - the loneliness and emotional neglect of her childhood - which must be acknowledged and healed if she was to truly find her way back into life. She learned that there are gifts in pain and tragedy, if you have the courage to look for them. And she came to understand just what the incredible love of her husband had brought her, and how hard it was to lose that. Written with warmth and humour as well as searing honesty, this book takes an unflinching look at both what it means to grieve, and what it means to love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Great Below

A journey into loss

Maddy Paxman

The Great Below

A journey into loss

Published by

Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court

South Street

Reading

RG1 4QS

UK

www.garnetpublishing.co.uk

www.twitter.com/Garnetpub

www.facebook.com/Garnetpub

blog.garnetpublishing.co.uk

Copyright © Maddy Paxman, 2014

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by

any electronic or mechanical means, including information

storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing

from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote

brief passages in a review.

First Edition

ISBN: 9781859643785

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset bySamantha Barden

Jacket design byArash Hejazi

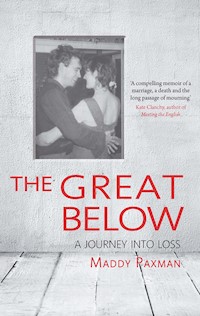

Cover imagesEmpty white interior of a vintage room without ceiling from grey grunge stone wall and old wood floor © cluckva, courtesy of Shutterstock.com and photo from the author’s private collection

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected]

‘From the Great Above she opened her ear to the Great Below.’

From The Descent of Inanna, translated from the Sumerian by Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer.

‘He says the best way out is always through.

And I agree to that, or in so far

As that I can see no way out but through . . .’

Robert Frost, ‘A Servant to Servants’.

For Michael, who I wish had been able to read this, and for Ruairi, who I hope one day will.

Preface

My husband, the poet Michael Donaghy, died on Thursday 16 September 2004, having suffered a brain haemorrhage the previous weekend. He was fifty and I was four years younger. It was one of those bright, crisp autumn days in a whole week of beautiful days. I stood at his feet and held on to his dear familiar toes, as if still trying to ground him, while the nurse removed the breathing tube. In the process she accidentally scratched his throat, which made him utter a choking cough; it was the first time since he became unconscious on Sunday that I had heard the sound of his voice and the last time I ever would. ‘Sorry, Michael, so sorry!’ she said.

For a moment, it wasn’t clear to me what had happened; I asked: ‘Has he gone?’ and she said yes. He quickly began to turn blue, as I had been warned. I laid my head on his chest where I could hear his heart still beating strongly; it continued to do so for what seemed ages and I thought how much Michael had worried about his heart and yet here it was, almost outliving him with its sturdy rhythm. ‘Silly bugger’, I told him quietly. But then the sound came to an end and he was still. His skin colour began to return to pink. My sister was weeping quietly but I felt calm, almost euphoric.

We had been given a quiet curtained-off space in an empty ward for the end game. The ward sister, whose shift had officially ended at lunchtime, had stayed on with us into the evening to be with us through the death, like a midwife for the end of life. (In the old days it was the same women who guided people into life and out of it: both assisting at births and laying out bodies for burial.) This, on a busy neurosurgery ward where many patients do not survive, was the most generous of acts; we felt held, contained, but never hurried.

In a version of an age-old ritual I had helped to wash Michael’s body in preparation; they let me cut his toenails and I noticed that, ironically, the terrible athlete’s foot which had recently been giving him such trouble had completely cleared up. The nurse gave him a shave, a job she said she liked, but nothing could be done about his hair which was still matted with blood from the operation that had cut open his skull, and was now stiff with sweat. Finally we dressed him in a fresh hospital gown; printed in yellow and red with the words ‘For hospital use only’, it reminded me of a hamburger wrapping.

I would have liked to have candles or anointing oils but Health and Safety forbade them. So instead we had a little interlude of poetry and song to send him on his way. I recited ‘The Present’, one of his poems, from memory, getting the last line slightly wrong. Then I sang a song that I used to sing to him when we were young and first in love: ‘To Althea from Prison’ with words by Sir Walter Raleigh set to an Irish melody, a song about how the spirit can be free even when the body is in chains. For good measure I ended with a funny song Michael had made up for our eight-year-old son, Ruairi, which begins ‘You’ve got to keep a chicken on your head . . .’

Outside the light was fading and inside the ward lights were dimmed, so the room had a grey peacefulness about it as we said goodbye. I’ve thought a lot about those final moments: how we made the choice which modern medicine has created for us, whether to continue to keep someone artificially alive or let them go. In effect, we finished him off like a wounded animal. What an awesome and awful task to have to perform as a doctor or nurse, no matter how used to death you have become. The final checks – pulse, temperature, a torch flashed in the eyes to see if the pupils are at all reactive – still no contraction, clearly brain-dead. And then we unplug him.

At the very moment of his dying a close friend of his called the hospital; she had heard him call out her name quite loudly inside her head. Another friend reported feeling a sudden sense of peace, the fretful anxiety of the past few days lifting like a cloud. One of our son’s teachers later told me that she had felt suddenly breathless at that particular moment, and had a sense that it might all be over. Several of Michael’s friends told me of dreams they had that night; one dreamed that she and he were lying flat on the ground in New York, making ‘snow angels’ by flapping their arms to make the imprint of wings. He told her: ‘I used to worry a lot about this, but it’s really fine.’

Afterwards he lay on the bed, seeming no more dead or alive really than he had been moments before, than he had been for four days. I wondered how I would possibly be able to leave, to take the last sight of this man I had loved for twenty-one years, who had been my soul-mate, best friend, co-parent, latterly husband, and also my burden. But as I sat on, my thoughts turned to Ruairi who was with a close friend, and it was like hearing a call from life to come, pay attention. ‘Let the dead bury their dead.’ I paused at the curtain, looked back once, left.

Chapter 1

The haemorrhage happened on Sunday morning, 12 September 2004, although it had probably been developing for a few weeks previously, during which Michael had had a couple of strange fainting spells. We had spent the past week in Spain, where he was teaching a residential poetry course, and I was trying, not with great success, to hijack it into a family holiday; combining work and leisure is never a wise gambit but it was often the only way I could persuade Michael to go away.

The course was held in a beautiful villa in a small town perched above a valley full of lemon and almond trees, up in the mountains inland from Alicante. Things got off to a bad start when I realised on the plane that I’d forgotten my driving licence and we would be unable to hire the car we’d booked; we had instead to take a long, winding minibus trip up to the village, which made both Michael and Ruairi travel-sick. Thereafter we were effectively stranded there for the week in 40-degree heat; I lay in the shade reading and Ruairi spent the day jumping in and out of the freezing ‘infinity edge’ pool, or looking for small lizards in the cracks of the stone walls. One night I dreamed that while roller skating he had rolled off the side into the pool, and I could see him lying there at the bottom with his eyes open. I knew I needed to save him, but I too had roller skates on and was afraid if I jumped in I might sink. Later, seeing Michael unconscious in hospital would remind me of this dream, as though it had been a premonition.

Michael was working practically all the time; the programme was very full, including evening sessions, and even when off-duty on residential courses you have to socialise with the students. He had been feeling very unwell – sick and groggy – ever since our arrival and one morning almost passed out while teaching. We put it down to intolerance of the heat; despite growing up in stifling New York summers, he had suffered severe heat-stroke on a trip to Mexico City a few years before. Our hosts suggested he see a doctor, but he had very recently been to see our GP in England, and was I think slightly anxious about the language barrier. Besides, as he was someone who never felt in the peak of health, with a constant stream of amorphous and shifting symptoms, it was hard to take all of this very seriously.

We spent hardly any time together that week, and when we did there was an undercurrent of griping anger and frustration. Despite the kind attentiveness of our hosts, I was bored and lonely; he was sick and stressed. It’s strange and sad to think now that in our last week together we were so far apart, in the way that only a warring couple can be. I remember just one evening when, alone together on the terrace after dinner, our old connection seemed to flower and we held hands and looked out in wonder at the thousands of stars hanging over the dark valley. In the distance you could hear sounds of fireworks from another village – a wedding or fiesta – but we stood there together in the quiet of suspended time. In some ways I think of this as our last moment of peace, a brief taste of eternity.

As we left the villa on our last day I picked a very ripe fig from the tree behind the house – one of only two left on the tree. It had the most astonishingly intense flavour and sweetness, and suddenly I understood all those fairy-tales and myths where you eat the forbidden fruit and are forever enchanted. Something in me demanded more, immediately! There was, however, only one more fruit and it was hanging way out over the ravine where I would probably kill myself trying to pick it. I left with the taste of a new experience, a new sensuality, in my mouth that seemed almost a glimpse into another way of interacting with the world.

The irritable mood between us persisted through the journey home and the business of unpacking and doing laundry, the burden of which always seemed to fall on me. The morning after we got back Michael was due to play an Irish music gig with an old friend, and though he woke up feeling worse than ever he was determined not to let them down. I suggested he go back to bed for a while and that I would call him when it was time to leave. I was hanging out the washing in the back garden when he yelled down in panic through the open bedroom window that he couldn’t move his left arm and leg. My first reaction was ‘What NOW?’ and I’m not proud of the way I dealt with him that morning – brusque and irritated when he was obviously quite terrified. Of course, had I known what was coming I hope I would have found it in me to be kinder.

To be fair to myself I had lived for years with what I think of as poet’s hypochondria. Many poets are rather sickly creatures, prone to severe health anxieties and often taking to their beds – one I know even sees the doctor regularly for his hypochondriasis. A poetic explanation might be that the practice of their art keeps them too close to the higher realms for them to feel truly comfortable on earth. Then again, maybe they just spend too much time navel-gazing, being possibly the most self-absorbed of all artists. An old girlfriend of Michael’s warned me that the first thing he said every morning was ‘Ouch!’ and it’s true that something always hurt: a toe, an eyebrow, an internal organ. I look at it now as his body’s attempt to ground him on earth – saying ‘Hey! Here I am!’ He was capable of developing the most astonishing symptoms under emotional pressure, once sprouting a large egg-shaped lump on his back after we had had a row. Yet despite all this I hardly ever saw him take a day off work, let alone miss a reading. He once travelled to Glasgow to give a performance with a fever of 104 degrees and a swollen spleen that the doctor thought might indicate hepatitis. The show must go on.

Only a few months earlier he had set off on a reading tour of the US with what turned out to be a seriously inflamed gall bladder. He ended up in hospital having an emergency procedure to unblock the bile duct, but got up the next day to give the reading he was booked to do. One night in New York – I had tagged us along on the early part of this trip as well – I sat up keeping him company while he endured the excruciating pain in his guts brought on by an unwise glass of wine and it suddenly dawned on me that my husband, for all his anxiety and complaining, was incredibly stoic when it came to pain.

All this made it impossible to know when he was really ill and when it was just hypochondria as usual. Over the past couple of years there had been a succession of trips to A&E with suspected heart attacks, which are a common cause of anxiety in middle-aged men, especially if, like Michael, their father had died that way. He was finally diagnosed with a slightly unusual heart rhythm – ‘right bundle branch block’ – which was not life-threatening, but the slightest strange sensation in his chest would trigger a spiralling panic reaction; I often caught him anxiously holding a hand to his chest or surreptitiously taking his pulse. I found it very hard to take any of his symptoms seriously, even when he was strapped up to monitors in a hospital bed; I just felt cross and put-upon. After a couple of these false alarms I even stopped going with him to the hospital, just packing him off in the ambulance alone.

I’m not sure why I always felt so angry when he was ill; perhaps it made him seem even more dependent on me than usual. I have had my share of illness and when I am sick I want plenty of attention and nurturing, which Michael was largely incapable of giving. He was broadly sympathetic, but assumed you just wanted to be left alone to sleep, whereas I wanted meals in bed, company, above all someone to take over my role as chief cook and bottle-washer. When I was little, there were rewards for being ill and I exploited this discovery frequently; it was practically the only time when I felt I got my mother’s full attention. I would be tucked up in her big bed and assiduously mothered with bowls of bread in warm milk, read to or allowed to watch TV, treated with kindness and sympathy; whereas any kind of emotional difficulty on my part usually sparked a cold fury and withdrawal. Perhaps I felt that by being ill Michael was stealing my thunder, my rightful place in the sickbed?

That Sunday morning, the beginning of the end, I think I was both furious and frankly terrified. Here was I, struggling to keep things together and look after Ruairi, and Michael was starting yet another round of weird dramatic symptoms. He was correspondingly enraged with me for not taking him seriously and being so unsympathetic. Wearily I called out the ambulance, which arrived in record time. The paramedics didn’t appear unduly concerned about the fact that he was paralysed all down his left side; they refused to be drawn on causes but seemed to regard it as a temporary condition which would wear off. They carried him downstairs, loaded him into the ambulance and drove him to the hospital, not even turning on the blue light. I decided to finish hanging out the last load of washing before following on in the car with Ruairi; I can see now that I was acting pretty strangely in the circumstances.

When things go badly in hospitals they tend to go wrong in small increments; often no one thing is the tipping point into catastrophe but little by little the delays and misjudgements pile up. My experience of hospitals, particularly this one, over the years is that you arrive in Accident and Emergency thinking with relief, ‘Now I’m safe; I’ll be looked after.’ But then you are left languishing in a corridor or cubicle or waiting-room in what appears to be a hospital empty of medical staff: no information, no treatment, no one around to ask. If there are medical personnel in view they are always busy tapping into computers, or talking to each other and ignoring you. However serious or minor your problem, it seems the real action is always happening elsewhere and you must wait your turn. Although I know the Health Service is underfunded and overstretched, I can’t help feeling this is fundamentally a problem of management: a misunderstanding of the needs of anxious patients for reassurance and to be kept in the picture.

You would think that a fifty-year-old man brought in by ambulance and paralysed down one side of his body would be treated as a serious emergency, but it was at least two hours before we were seen by the first doctor. Many things were working against us that day. It was a Sunday morning in September, when all the new young doctors were starting their jobs – sweet and eager, they all looked about fifteen. There was, I later learned, a surge of ‘high priority’ cases who came in at the same time as Michael – though I would have thought he merited the same designation. There was also, amazingly, no consultant on duty, just one on call by telephone, which I still find extraordinary – allowing a large hospital emergency department, at the busiest time, to be run by less experienced and even junior doctors. Additionally, there are no radiographers in hospitals at weekends, owing to a national shortage: they too are on call and can be paged to come in, but of course that takes time (and costs money, no doubt). All in all we could hardly have chosen a worse moment.

This particular hospital, which is our local one, has always shown reluctance to use diagnostic technology. Years ago I was sent home bleeding internally from an ectopic pregnancy, because the single ultrasound scanner was being used on another ward; I almost died. On the other end of the scale, when I broke a toe I was lucky to be seen by an agency nurse who ordered an immediate X-ray. The doctor I saw afterwards told me they didn’t usually bother with this procedure, since there was nothing that could be done anyway. I pointed out to her that it made quite a difference to know whether I would be incapacitated for six weeks if it were broken, or a matter of days if it were only a sprain.

The atmosphere in the A&E was far from comforting. This was a large, busy inner-city hospital still coping with the fallout from Saturday night. After a few basic checks by a nurse we were abandoned in a grim curtained cubicle, from which I had to make constant forays through two locked doors: to the hospital shop for things to keep Ruairi entertained; and to make mobile phone calls outside the front entrance. Michael was unable to get up or even sit up, so when he needed to pee I had to ask for a bottle and hold it steady for him while he leant against me for support. (I remembered doing something similar once early in our relationship, when he was too drunk to get up the stairs after a party.) A violent patient locked in a room next to our cubicle and guarded by police regularly hammered on the door howling: ‘Let me out – I’m a DOCTOR!!!’ The ladies toilet was covered with blood and no one came to clean it all day despite my reporting it several times.

The angry tension between Michael and me continued, although I tried my best to override it. I knew I wasn’t behaving well but I think now that we were both acting out of fear: what if he’d had a stroke and was going to be disabled long-term? He certainly would not be a patient patient, and my life – and Ruairi’s – would be over. Eventually a young woman doctor came and took a medical history, then carried out a series of reaction tests that might indicate a stroke; she said it was probably a Transient Ischaemic Attack (a small stroke) and would resolve over the next day or so. She left saying she would pass him on to the ‘medical team’. You get caught up in this mysterious language in hospital – wasn’t she ‘medical’? I later learned that in her notes she had described Michael’s left-side paralysis as ‘weakness’ and wrongly stated the cause of his mother’s death as a heart attack.

As yet nobody seemed to be taking this very seriously, so consequently neither did I. At this point I was even thinking I might still make it to my book group that evening, leaving Michael safe in hospital. Accordingly I went to the shop again to buy him some reading matter he might like; I chose a science magazine with an article about how we are all made of stardust. Guilt comes with the territory of grief because when someone has died there is no longer a chance to put things right or say sorry. I regret now not being a better advocate, not making more of a fuss to get him properly diagnosed. But deep down I don’t believe that it would have made a difference to the outcome – his time was well and truly up. I sometimes think that our arrival in the A&E on that particularly chaotic day was essentially to speed him on the journey, because even if it’s remotely possible that he could have been kept alive by prompter treatment, it might well have been to a life worse than death.

We waited another two hours in the cubicle, during which time Michael repeatedly struggled and failed to move his left leg. If I lifted it up into a bent position for him he could, with tremendous sweating effort, thrust it straight. Ruairi became understandably fractious and bored; I was still trying to find someone to come and pick him up, but everyone I rang was out or otherwise occupied. The next doctor we saw, also young and female, asked the same questions about medical history and ran the same series of reaction tests; after four hours Michael was no better or worse, but no one seemed to know exactly what had happened. It made me long for the American system of over-investigating everything for fear of legislation, or at any rate for the wonderful fictitious urgency of doctors in TV hospital dramas like ER.

This second young doctor clearly fell in love with us as a family, or at least with the delightful man and the adorable child, who never failed to pull out the charm when it was called for, no matter how grim they were feeling. Once when Michael had a chest infection we called out the duty doctor for a home visit – bed-bound and hardly able to speak for coughing, Michael croaked ‘How are you?’ ‘I rather think I should be asking you that question’, she replied.

As I left the hospital later that evening, I would come across this young doctor crying and obviously quite traumatised on our account, being comforted by a senior colleague. It can’t be easy to lose a patient, especially if you are new at the job. Why are patients who come into A&E with potentially very serious conditions not seen by at least one senior doctor with good diagnostic experience? These young doctors were charming and cheerful as they filled in all the requisite boxes on the forms, but how could they be expected to know that the man in front of them might be about to die? Someone with more years on the job might have been quicker on the uptake.

The second doctor decided to send Michael for a chest X-ray and a CT scan, though it took three more hours for the appropriate technicians to arrive at the hospital. During this time a friend came to take Ruairi away; he arrived at an awkward moment and flung open the curtain when I was trying to help Michael pee, which led to a spillage. There really is no dignity in hospital. In the confusion, Ruairi was scooped up and did not really say goodbye to his dad – yet another regret of mine, as he would only see him again as an inert figure strapped up to tubes and machines. But it is really no use to think this way; it isn’t the final moments that count, but the lifetime of love that preceded them. And you don’t say goodbye to someone every time as though it might be the last, although we do have a family rule, passed down from Michael’s father, that you should never part in anger just in case.

From this moment on, things started to take a severely downward turn. I am composed of a strange mixture of optimism and pessimism (inherited from the personality extremes of my father and mother), so although I constantly anticipate and fear disaster there is a part of me that assumes things will turn out all right, no matter how bad they seem. It is still broadly my philosophy of life – that everything is for the best – but I’ve learned that sometimes things do have to get really terrible before they get to be OK. That afternoon things just kept getting worse and worse . . . and worse.

I had to help the nurse wheel the trolley through to the X-ray room. Where were all the porters? I had already assisted her in changing Michael’s soaked sheets and, although it makes one feel better to be doing something, I wondered how our hospitals would function without relatives, and what it would be like if you were there alone. When my mother was taken into A&E a couple of years ago I waited with her the nine hours it took for a bed to become available so that they could admit her. In the next cubicle a very old lady of a hundred and something lay dying alone. She had been brought in by staff from the nursing home where she lived and lay on the trolley weakly calling out ‘Nurse, nurse . . .’ in a frightened voice. Of course nobody came, so finally I went to her bedside and held her hand for a while, telling her everything was going to be all right. Is this really how we should die?

Michael and I were left alone in the X-ray waiting-room and it was at this moment that the tension between us finally broke. Michael suddenly began to howl in fear; I howled too and we clung to each other, weeping. Two smartly-dressed African ladies in the waiting-room stared at us in obvious astonishment, which turned our tears to laughter. Michael reached over and patted me on the chest with his fist repeatedly and urgently: ‘That’s where I am – love, love, love! Remember . . . love!’