Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

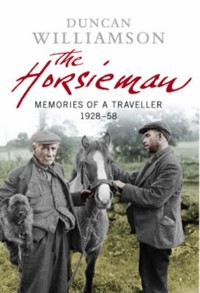

Duncan Williamson was the son, grandson and great grandson of nomadic tinsmiths, basket makers, pipers and storytellers. In this book, he describes his life as a traveller with verve, candour and intimacy, recounting a childhood spent on the shores of Loch Fyne, work on the small hill farms in the summer, walking with barrows and prams and later with horse and cart, the length and breadth of Scotland. He recalls camping with hundreds of traveller families from the 1940s to the 1960s, his marriage to his cousin, Jeanie Townsley, and all the various traditional skills and arts which must be perfected for a man to maintain his family adequately. The Horsieman is the story of traditions long vanished - of traveller trades, of building tents, of routes travelled and traditional camping sites, of stories, songs, music and cures which have been the heritage and tradition of travelling people in Scotland through the ages. Set mainly in Argyll, Tayside and all stations in between, Duncan Williamson's story is told with great warmth and humour and in the inimitable style of one Scotland's master storytellers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 714

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE HORSIEMAN

With over ten books to his name, Duncan Williamson was one of the last true, traveller horsemen and the best-known of Scotland’s storytellers. This autobiography tells, for the first time, his original story; how the Scottish traveller survived hawking his wares, dealing with local farmers and tradesmen, becoming a family man, creating the world of an unparalleled tradition-bearer. Duncan Williamson died in November 2007.

Linda Williamson, born and brought up in the woodlands of America’s Midwest, was educated at the universities of Wisconsin and Edinburgh, and received a PhD in ethnomusicology in 1985. She married Duncan Williamson in 1977 and they have two children. A devotee of Indian philosophy and literary editor of several collections of Scottish stories, she now lives with her son in Edinburgh.

This eBook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Duncan Williamson 1994 Preface copyright © Linda Williamson 2008

First published in 1994 by Canongate Press Ltd This edition first published in 2008 by Birlinn Ltd

Illustrations by Neil MacGregor Map of Duncan Williamson’s route by John Fardell

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-84158-692-2 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-527-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

CONTENTS

MAPS

PREFACE

1 JOCK AND BETSY AND THE KIDS

2 THE SOLDERING BOLT

3 MY MOTHER’S PENSION

4 SANDY WAS AN ORIGINAL TRAVELLER

5 GIE ME A HAUD O YIR HAND!

6 THE HOOLET’S NEUK

7 WHAT THE FAIRIES ARE PLAYING

8 A TRAVELLER HERITAGE

9 BEGGARS, THIEVES AND STRANGERS

10 SILVER AND THE SHAN GURIE

11 BY GOD, LADDIE, YOU’RE GAME!

12 DO YOU BELIEVE IN EVIL?

13 THE SECRET OF TRAVELLER TRADE

14 A GREAT HORSIEMAN

GLOSSARY

PREFACE

The Horsieman is the story of Duncan Williamson’s life on the road as one of Scotland’s travelling people from 1928 to 1958. Composed in late 1980 and early 1981 with the help of a grant from the Scottish Arts Council, the narrative was recorded over thirty hours on to twelve reel-to-reel tapes. These tapes, an oral history testament, were transcribed and edited by myself, Duncan’s second wife. Our working title was Horse Dealing and Traveller Trade, an exposition of how traveller families in Scotland survived by their wits and traditional skills. The language is racy and laconic, colourful and spirited as Duncan was still very much part of the travelling fraternity in 1980 – working as a general dealer in close touch with many hundreds of traveller friends and relations.

The opening chapter, a brief account of Duncan’s early family life, recorded at the request of his publisher, Stephanie Wolfe-Murray, in 1993, differs linguistically from the balance of the book. The narration held more English, less Gaelic and traveller cant; a transformation to which I contributed, that story told below. To help the reader with comprehension, a full glossary of Scots, traveller cant and Gaelic words finishes the book. Supplementing the text of The Horsieman are maps of travel routes, camping places, villages and farms where the tapestry of Duncan’s life was woven. In the plate section, sketches taken from Duncan’s notebook of poems and song show his drawings of traveller tents and the tools of traveller trades, skills now nearly lost and forgotten; we give hearty thanks to Neil MacGregor for helping with these. An oral historian in his own right, Neil has been a constant support throughout the work.

According to Duncan, there could be no real story without a song; and every chapter of The Horsieman closes with a poem, traditional song or ballad which Duncan wrote or sang. Wrapped up in these songs is a deeper story, of the writer who is responsible for all of the storyteller’s words in print: a newcomer to Scotland in 1974, I followed in small footsteps behind the indomitable Hamish Henderson as a collector of songs and ballads for doctoral work in ethnomusicology.

The tattie howkers are rained off today and they say I will find Duncan Williamson here in this potato field near Crieff. Inside a tent on his knees singing ballads to his traveller friends I meet him, a widower aged forty-seven. He always said it was the Broonie, the spirit of a generation and Duncan means ‘brown head’ in Gaelic, because a year and a half later I marry him, in 1977. Living the life of the Scottish Travelling People, we are tented in a gelly – in summer months on Loch Fyne in Argyll, in winter months returning to Fife, up the Ceres Road from Cupar to Tarvit Farm. By 1980 our second child Tommy is in his second year, Betsy is aged three, and from August to September my mother has been to visit us at Duncholgan near Lochgilphead, staying in our extended gelly, made a third longer at the back to accommodate Granny from America. With heavy rainfall and high winds, Argyll is harsh in the winter and Duncan has few prospects for hawking, dealing in scrap metals. His buyer, Davie Band in Perth, is just over the hill and down the road from Glen Tarkie in north-east Fife. So, how wonderful to receive the letter from Mr and Mrs Bell on Kincraigie Farm above Strathmiglo who say ‘yes!’ Duncan should come again to help with farm work in exchange for the cottage beside the bothy at the back of the steadings. Great! Our first solid roof and floor, and farewell to life on the road, a decision we make for the sake of our weans, Betsy and Tommy, after all.

The Scottish Arts Council have awarded us a bursary (September 1980) to write Duncan’s life story. His traditional folk tales are finding their way into the archives of the School of Scottish Studies through fieldwork recordings by various university students and doctoral candidates like myself; one literary agent and author armed with a handful of my transcriptions is trying to get an Edinburgh publisher interested in Duncan’s mine of stories. Fife, close to Perth and the capital, is a good place to put down roots. We begin work on the autobiography the first week resident in Kincraigie.

Duncan knew in his heart his traveller life was over. His American wife, a thirty-one-year-old academic, had weathered nearly five years as a nomad but the hardships and uncertainties were taking a toll on her health, and with two kids growing like weeds he needed to provide a secure home. Davie Bell, laird of Kincraigie, had been host to his first family of seven since the 1940s. And here in Fife Duncan had become a tradesman, a real horsieman in the fifties. But normal settled life was never going to happen; we would not take charge of our lives, for the world was already keenly aware of the master storyteller, whose recordings had been whirling through the Edinburgh offices of the School of Scottish Studies, stretching into the bowels of the storytelling revival. What began as occasional recording sessions for students from America, Japan, Germany and all the isles of Britain, Canada and beyond soon became a weekly feature of Kincraigie life. Grampian Television, Central ITV and BBC Two camera crews found their way to the rocky hill at the back of the farm where lived the extraordinary tradition bearer who could tell stories for days on end showering guests with his renowned Celtic hospitality. Duncan’s life story was shelved for ten years while the Broonie, the hedgehurst, the unicorn, fairies, silkies and woodland elves sprang from his breath into the minds and imaginations of pilgrim storytellers ‘from the Alaskan North to the Antipodean South’, writes David Campbell, ‘all making tracks to Kincraigie Farm.’ Publicly recognised as Scotland’s living national monument, news spread like wildfire over a short space of ten years and such accolades as ‘the greatest living English-speaking storyteller’ were commonplace.

From this period comes my favourite horse story of Duncan’s.

I heard this many many years ago when I was just a kid back home in Argyll. It is a very old story. Now once upon a time there was this knight. And he had this horse, oh, what a beautiful horse! It was snow white. And the knight thought the world of it, took it with him to all the battles and every place he went all over the country. And everybody admired this horse. Then one day when he was older, the knight took his horse home and put it in the field next to his house.

Now down in the village there was a bell. And whenever anyone wanted to spread news, because there were no newspapers in these days, if anybody wanted to tell something, they went out in the street and pulled the bell. The bell went; ding dong ding dong ding dong. And all the people gathered round about. A man told what was going to happen, if there was anything going on in the village, if anybody was hurt or anything important! But years passed and things changed, and the bell was never used. It was forgotten about, just like the poor old horse. But the old horse was still in the field only getting very, very little to eat. The knight was now very old and he had completely forgotten about his horse. Then one day the gate leading to the field was left open. The old horse got out.

And he was that weak he could hardly stand. So he just barely managed to wander down the street, right by the knight’s house, down through the village till it came to the old church where the old bell was. And all of the old church was covered over with ivy. The old rope that was hanging from the bell, all the creeping vines had gathered round it and the rope was nearly covered – you could hardly see it but the bell could still ring! So the old horse searched about for something soft, because he had no teeth to eat. And the first thing he saw was the vines hanging to the bell. He started pulling them and the bell started to ring: ding dong ding dong, someone has done a wrong.

And all the villagers listened. Some of the old folk in the village who remembered . . . when the bell used to ring when someone had done a wrong, or if somebody had done something good, all came out. Some on crutches, some with staves, old women, old ladies well up in their years, in their seventies and eighties, and they gathered all round the bell. And they stood and they looked.

The old horse was pulling the ivy off the bell rope. It was going, ding dong ding dong, someone has done a wrong. And they saw the old horse. One old man stood up.

‘I remember that horse,’ he said. ‘That was a beautiful animal. It had no other way to come and tell us that its master had starved it nearly to death. Look at it! Its bones are sticking out; its ribs are sticking out of its side, and its hip joints. Look at its tail! It’s never been combed for years, neither has been its mane. Its master has done it wrong after all these years, and he will have to be punished.’

So all the people of the village gathered and went up to the knight’s big house, knocked at his door and told him to come out. The old knight came out. He said, ‘What do you want?’

They said, ‘We want you! You’ve done a wrong.’

And the knight said, ‘I’ve never done a wrong in all my life. I’ve been a knight to the king all the days of my life.’

The old man said, ‘You have done a wrong – you’ve neglected your old horse.’

‘My horse?’ says the knight.

‘Yes,’ said the people of the village. ‘Your old horse came down to the village and rang the bell himself, told us that you had done a wrong.’

‘Well,’ says the knight, ‘if that’s true, he’ll never be neglected again.’ So the knight took his old horse back up to his big house. He put him in a warm stable and looked after him, saw that the horse had plenty to eat and plenty to drink for the rest of his days. And that’s the last of my story.

It was a special privilege to be able to look after Duncan in the last five months of his life. We spent the previous thirteen years apart, since 1994 when The Horsieman was first published, but I never forgot the knight and his steed, or the Broonie! His songs and stories remained an integral part of my own travels, my own story. In July 2007 he taught me the verses of ‘The Golden Vanity’ closing chapter five below. And asleep in the room at the end of Duncan’s house, I dreamed the Night of Peace, our Christmas tree alight with candles under canvas in the woods of Tarvit Farm. On Hallowe’en night after a sweet fireside ceilidh in song with his Ladybank neighbours, Duncan suffered a stroke, and eight days later in hospital my husband died. Now, a soulful legacy, storytellers mourn their loss. Colleague Hugh Lupton pays last respects to Duncan Williamson, a tribute to his artistry:

Everything he heard, saw, touched, smelt, tasted and felt added flavour to the bubbling stew of stories he kept in his memory. He’d lived an extraordinary life to the full. He’d known how it was to be starving hungry, to be kept awake all night by seals with tooth-ache, to fit a cast-off horseshoe, to guddle for trout. He’d experienced loss and love and the pleasures of good company, he’d trodden the roads of Scotland over and over . . . all this fed into his stories, giving them substance, sympathy, humour, a grounding in real places and all the insights that come from a life of hard graft and sharp, humane observation. He might be telling a Jack tale, a silkie story, a joke, but in his imagination it always rested on a solid core of real lived experience that made the story true. Also, through his vast inner store of ballads and poems, through his knowledge of Gaelic and cant, he had a rich and rare vocabulary and a deep feel for the music of language. He was quite simply, the greatest bearer of stories and songs in the Scots and English language.

Excellent recordings of Duncan Williamson’s soulful tenor, his ballads and songs, may be heard on the CDs produced by Mike Yates (Travellers Joy), John Howson (Put Another Log on the Fire) and Pete Shepherd (FifeSing). Available from Music in Scotland Ltd are two volumes of Traveller’s Tales, including ‘Closing Our Camping Grounds Down’ by Duncan, also known as ‘The Hawker’s Lament’.

From the Celtic otherworld, the rest is left to our horsieman. May the reader find below something of the profundity and gentleness of the man, as Helen East remembers, ‘who did his utmost to make sure we have his stories.’

Linda Williamson

November 2007

CHAPTER ONE

JOCK AND BETSY AND THE KIDS

Some travellers stuck more to one area. But Johnie Townsley, my mother’s father, travelled all over. He walked along with a handcart and went to Inverness, Elgin, right down into Ayrshire and down to Dumfries. He travelled all through Fife, Angus and Perthshire – no, not in the wintertime, just in the summertime. But you see, he was a piper and a horse was no good to him. He played his bagpipes in the summertime, by the shooting lodges, big houses, hotels and that. And then he came back home to Argyll and settled down for the winter. In the summertime he took off again with his family.

My mother’s mother was old Bella MacDonald. She told me that her grandfather, Roderick MacDonald, used to travel with a pony through the paths to the farms, taking the shortcuts over the hills. Roderick carried his gear, a bundle tied to each side of the pony’s back with a couple of kids sitting on, and he led the pony all through Argyllshire and Perthshire. Taking carts through these roads was no good, because the wheels broke and the paths were too narrow.

On my father’s side, my grandfather Willie Williamson, born 1851, never travelled at all once he had children, since long before the 1914 war. And I remember my father telling me that his grandfather on his mother’s side, John MacColl (whose father was from Ireland) travelled with horses with sackets on their backs. They were pack folk, like the way the cowboys went with pack mules.

John MacColl was born in Kilberry in 1812. His father was a tinsmith, but John liked to work as a coppersmith. He used to go with a one-wheeled barrow, like a wheelbarrow but it had no sides. My mother told me that he travelled the footpaths from place to place because the roads were very bad in these days. He took all the shortcuts across the hills and across the mountains carrying these big sheets of copper on his barrow. And my mother told me how he came to this farm away in the back highlands of Argyllshire.

The farmer said to him, ‘John, that’s an awfae bundle you’ve got on that barra. Would ye no be better wi a bit pony tae pull that bit cart tae youse, instead o pushin that thing across the mountains and across footpaths?’

‘It might be all right,’ he says to the farmer, ‘but I couldna get gaun across my paths across the hills wi a pony.’ But he took the pony from the farmer anyway, bought it from him and he threw away the barrow, tied the bundles on the pony’s back. He walked with this wee piebald pony through the moors; let it carry his stuff.

But travellers were very poor before they had ponies. They couldn’t do much for themselves, and they couldn’t carry very much. For the want of carrying more it made them poorer still. Their camping stuff was as light as what they could carry on their backs. It was okay if they had a big family, see what I mean, two-three boys or two-three lassies. Like our family when we went on the move in the summertime. Every one of us carried something of the equipment. But if we’d had a pony, if my father had had a pony, then we could have been a bit better off. Some carried the sticks for the tent, some carried the tent canvas, some carried the cooking utensils and some carried the bed clothes in our family. Everybody had their own thing.

After travellers managed to see the sense of having a horse, getting a pony, buying a cart and harness, they went further afield. They could travel farther. Some Highland families left and travelled into other ‘countries’, Perthshire, Fife and Angus, the ‘low country’. But while it started the travellers and made some of them a wee bit better off, there were some who never bothered with horses at all. They still maintained it was too much bother, especially in Argyllshire among the Townsleys, my mother’s people. They bothered very little about horses because they were afraid of burkers, or body-snatchers. These travellers could lift their barras over a fence, lift their wee handcarts or perambulators over into a wood or take them up an old road where they couldn’t take a horse and cart – well away from the main roads at night-time. This was handy to them. They didn’t keep ponies, because they didn’t want to be close to the road when the coaches passed. Before the days of motor cars they believed all coaches were driven by burkers, who took your body and sellt it for research.

My father John Williamson was born in 1892. He came off the Williamson and Burke families (Nancy Burke was his paternal grandmother) who originally came also from Kintyre, whose forebears came from the Isle of Islay. After my father and my mother were married in 1910, they travelled on foot after that around Scotland in the years before the beginning of the First World War. My father was called up in the Army and joined the war in 1915. After he served his time he came back from the Army, and he had two sons Jock and Sandy by then. And he settled in Furnace on the shores of Loch Fyne.

On Loch Fyne, in Furnace wood, my father raised thirteen children. Sixteen were born, but three died in infancy, one when she was just a newborn baby, and she was born in a hospital. Everyone else was born in a tent, apart from Susan, whom my mother had among the heather! I was born by the shoreside. It was early spring. And he put all of us to school in Furnace and took care of us to the best of his ability. My father didn’t have a regular job because in these days a tinker was looked down upon, as someone that was socially unfit to work among the common folk. But my father being settled in the one part, and putting us to school, the stigma of being a tinker naturally passed by as most of the folk came to know and understand us. We were called and accepted by the local community as ‘the Williamson family’. My father was respected because he’d served his time in the war, and he had come home and registered the marriage to my mother (1916 in Kilmichael Glassary) and had settled down. When a traveller did these things and showed that he tried to make himself part of the community, he gained a little respect from the local folk.

My mother and father ran away together when my mother was only fourteen years old. And my daddy was seventeen. Betsy Townsley was my mother’s full name. And she was born in a cave in Muasdale. My daddy was born in an old mill away up Tangy Glen. And the old mill was owned by two old brothers. One of the brothers was blind and they ran the old mill. They left this shed open with some straw in it for the runaway marriages of Kintyre. It was like Gretna Green! And when two people ran away together and spent a night in the mill they were officially married.

But my mother and father lived in the wood together in Furnace. It was a big oak wood in the middle of the Duke’s estate. And people tried to get us moved on from that wood, but my grandfather was born there, my mother’s father. And of course the old duke, Duncan Campbell in Argyll, my father was a great favourite of his. Because I remember he came with his old car on a Sunday with a big bunch of lollipops, all those different colours you could ever see!

And he said, ‘Well, Mr Williamson, I will pay the doctor’s bill the next time. Are the children around?’ And he wore these plus fours, we call them knickerbockers; and big old brogue shoes, a Balmoral Bonnet and sometimes the kilt. He sat down there and took off his old shoes and we watched him! My daddy strapped the razor on his belt, a big open razor. We wondered what he was going to do. And the old duke took his foot up, put it on my daddy’s knee. And his old foot was full of bunions and corns. He was an old man, in his seventies at that time, when I remember him. And Daddy very carefully shaved the skin of his foot, shaved the bunion and the corn with the open razor. And this took away a lot of pressure from it, at the head, the little corn on his foot. Daddy cut it in with his razor and shaved it all right round, and he clipped the nails of his toes with the razor. The Duke wouldn’t go anywhere else! But he would come once a month or so, drive his car down. And people would say to the Duke, ‘Oh, these tinkers, they’re cutting your trees.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘let them cut my trees. They’re my trees!’

And of course we used to steal a few apples from people’s gardens and we stole a few vegetables. And if we came across a nest of eggs by a hen, we took them! Because the wintertimes were very hard. The summertime was nice because we would run about with our bare feet, and Daddy would take us on a camping trip then. He’d burn the old barricade, the tent we lived in during the winter, and take us on a trip down to Lochgilphead, around Kilmartin among the standing stones. And we would play ourselves there and have fun. We’d thin the turnips on our knees and have a wonderful time because Daddy and Mammy were always there. They would work hard, have a wee dram at the weekends, sing songs and Daddy would play the pipes.

Then he would say, ‘Well, children, you’ve had your holiday. It’s time to go home.’ And then we would go back to Furnace again, back to the same place. There’d be nothing there, just a piece of ground, hard baked. We built a new barricade tent every autumn in the same place. No grass would ever grow there. Father even used the same holes in the ground, where he’d put the sapling sticks in with the snottum. And he was thirty-seven years in that one little camping place! All his family grew up there. He put them all to the little school in Furnace, so they could learn to read and write.

These summers in the 1920s started early. You got beautiful weather in the month of April. On the tenth of April this year Daddy burned the big barricade and packed all the things he would need for the summer. He got the weans ready, there were six by that time. And my mother was busy expecting. She must have been nine months on the way.

He said, ‘Well, Betsy, we’ll get the length of Lochgilphead, which is sixteen miles. And if you take ill with the baby down there, maybe they can get you into hospital or something.’ She had never been in hospital in her life. Old Granny used to do this, be her midwife. That was my mother’s old mother, Bella MacDonald, the old storyteller and fortune teller. But father never went far that day, only about three-quarters of a mile on the first day of the journey. He pitched three little tents, one for the girls, one for the boys and one for himself and my mother just at Furnace shore. And the next morning Mother took ill. That was the eleventh of April, 1928. I was born in the little tent, and Daddy took the other children along the shore for a walk while my granny took me to the world.

I always tell people, ‘I was born before my granny!’ And my mother took me wrapped in a shawl later that day, for she wanted to show her new baby to all her old friends. And some of the old people kept a diary of my mother.

They said, ‘Betsy, which one is this?’ Some of the old ladies in the village, maybe old spinsters she visited who never had any children of their own, or maybe some with their children grown up, said, ‘Well, Betsy, which is this one?’ My mother was only a young woman at that time.

‘This is my seventh,’ she said.

Now the villagers of Furnace knew the time had come, that Daddy had burned his barricade and we were going for our summer’s trip. ‘Oh,’ they said, ‘there’ll no be many eggs stolen again for a while!’ And of course, every one of my mother’s friends knew my mother was pregnant. And they probably wished the baby would be born in Furnace, like some of the other ones.

But this particular day a dear friend of my mother’s died, the same day in 1928 I was born. Duncan MacCallum. He died with TB, tuberculosis. He was a great shinty player. His brother Archie had heard that my mother had had a wee baby. And his mother and my mother were great friends. He cycled from Furnace down nearly a mile to the shore to the tents. And he told my mammy and daddy that young Duncan had died. Somebody had spread the word, somebody was out on the road that morning and had said, ‘What’s wrong? Johnie’s walking with the weans. Oh, Betsy’s haein a wean.’ And the word spread back to the village. Betsy had never got to Lochgilphead. Betsy had the baby at the shore, at Furnace shore. And Archie took his old bicycle and cycled down. My granny by this time had tidied me up and rolled me up in a bit of cloth or something, whatever it was, and had tidied up my mother. And Archie came to the fire at the front of the tent. Father had a wee fire there with the door of the tent pulled down for my mother to have a little privacy.

He said, ‘Duncan has died.’ Duncan was only twenty-four.

And my mother said, ‘What’s that? Duncan has died!’ Because she knew Duncan had been ill.

And he said, ‘Have you a boy or a girl?’

She said, ‘It’s a wee boy.’ And my mother cried out, ‘Well, I’m going to call him Duncan!’ And she called me Duncan MacCallum Williamson. And Duncan MacCallum had died two hours before I was born. And she said, ‘Well, we’re going to call him Duncan after Duncan MacCallum.’ And of course Archie was really chuffed, really proud. And they were good people. Soon my mother was up and she walked to old Katie MacCallum, young Duncan’s mother and showed her the baby – me! And Mother told her she was going to call it after Duncan. They were quarry workers who stayed in Furnace. And of course they were so pleased that Duncan’s name would be carried on for years.

My father stayed for a week at the shore after I was born. By then my mother was a little stronger – she was a strong woman after having all these children. And we shifted. She took me and showed me off to all her friends, all round Minard. My father stayed there for a few days. Oh, that was the idea! Handsel the baby, give the baby a silver coin, a sixpence or threepenny piece or a shilling. My mother would collect several shillings, a lot of money! She’d say, ‘Oh, Mrs such-and-such, this is my new baby!’

‘Oh, I’ll have to give the wee baby something.’ And she collected seven or eight shillings in a day. In 1928 that was worth a fortune to you. And they made their way to Lochgilphead. And he had friends there, and this was Betsy with her new baby! I was a kind of pension to her for the first three months of my life. And Father cut a little hay, tied a little corn, and worked on a few farms till the days got shorter. Then he made his way back to Furnace again, put up the barricade once again and sent the children to school – Sandy, Jock, Bella, Betty, Willie and Rachel. My mother took care of the baby, walked back to Furnace and showed me to the rest of the old friends who had never seen me yet.

And then the cold winter nights, Granny went into her little compartment, tent, in the barricade, and it was storytelling. I was very young then, but I remember my granny well. There were wonderful stories told round the little fire. I remember my daddy sitting around the fire in the middle of the floor, just a stick fire in the middle of the tent, a hole in the roof and the smoke going straight up through the hole. A little paraffin lamp, the cruisie turned down, home-made by my father.

Granny would tell a story, Father would tell a story. Maybe a few travellers passing by would stop and put their tent over in the ‘Tinker’s Turn’, a place across the burn from the wood where we stayed. My father’s cousin Willie Williamson, old Rabbie Townsley and some of the old travellers, Sandy Reid and others would come in. They would also tell stories and have a little get-together. Our tent was a stopping place for travellers who came down to Argyll, and there was always time for a story.

Now Granny would stay with us all winter in that big barricade with her little compartment. Her son Duncan was there as well. He helped my father to get firewood, and they’d go fishing together, catch a few salmon and snare a few rabbits. Granny went hawking with my mother through the houses in Furnace and Minard. But also some days Granny took off on her own and it was our love to go with her. Granny was wonderfully good to us. Whatever she got, something tasty, she would always share it with us. In the summertime when the days got warm, my father would dismantle the tent, the big barricade; and Granny would move her little tent away from our big one to have some privacy of her own. Just because it was so warm.

Now Granny was an old lady, and every old traveller woman in these bygone days never carried a handbag. But around their waist they carried a big pocket. I remember Granny’s – she made it herself, a tartan pocket. It was like a large purse with a strap, and she tied it around her waist. It had three pearl buttons down the middle, no zip in these days. Granny carried all her worldly possessions in this pocket.

Now, Granny smoked a little clay pipe. And when she needed tobacco, she would say, ‘Weans, I want you to run to the village for tobacco for my pipe.’ And she’d give us a threepenny bit, a penny for each of us and a penny for tobacco. The old man used to have a roll of it on the counter, and he cut off a little bit for Granny for her penny. We came back and our reward was, ‘Granny, tell us a story!’

She sat there in front of her little tent, and she had a little billy-can and a little fire. We collected sticks for her, and she’d boil this strong, black tea. She lifted the can off, placed it by the side of the fire and said, ‘Well, weans, I’ll see what I have in my pocket for you this time!’ She opened up that big pocket by her side with the three pearl buttons. I remember them well, and she said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you this story.’ Maybe it was one she’d told three nights before. Maybe it was one she had never told for weeks. Sometimes she would tell us a story three-four times; sometimes she told us a story we’d never heard.

So, one day my sister and I came back from the village. We were playing and we came up to Granny’s little tent. The sun was shining warm. Granny’s little can of tea was by the fire: it was cold, the fire had burned out. The sun was warm. Granny was lying, she had her two hands under her head like an old woman, and her little bed was in front of the tent. By her side was the pocket. That was the very first time we’d ever seen that pocket off Granny’s waist. She probably took it off when she went to bed at night-time. But never during the day!

So my sister and I crept up quietly and we said, ‘Granny is asleep! There’s her pocket. Let’s go and see how many stories are in Granny’s pocket.’ So very gently we picked the pocket up, we took it behind the tree where we lived in the forest and opened up the three pearl buttons. And in that pocket was like Aladdin’s Cave! There were clay pipes, threepenny pieces, rings, halfpennies, pennies, farthings, brooches, pins, needles, everything an old woman carried with her, thimbles . . . but not one single story could we find! So we never touched anything. We put everything back inside, closed it and put it back, left it by her side. We said, ‘We’ll go and play and we’ll get Granny when she gets up.’ So we went off to play again, came back about an hour later and Granny was up. Her little fire was kindling. She was heating up her cold tea. And we sat down by her side. She began to light her pipe after she drank this black, strong tea. We said, ‘Granny, are you going to tell us a story?’

‘Aye, weans,’ she said, ‘I’ll tell you a story.’ She loved telling us stories because it was company for us, forbyes it was good company for her to sit there beside us weans. She said. ‘Wait a minute noo, wait till I see what I have for you tonight.’ And she opened up that pocket. She looked at me and my little sister for a while, for a long time with her blue eyes. She said, ‘Ye ken something, weans?’

We said, ‘No, Granny.’

She said, ‘Somebody opened my pocket when I was asleep and all my stories are gone. I cannae tell ye a story the nicht, weans.’ And she never told us a story that night. And she never told us another story. And I was seventeen when my granny died, but eleven when that happened. Granny never told me another story, and that’s a true story!

Life was very hard for us as a travelling family living on the Duke of Argyll’s estate in Furnace in Argyll, because it was hard to feed a large family when times were so hard. We ran through the village and we stole a few carrots, stole a few apples from the people. Some of the local people respected us, some didn’t want their children to play with us. We were local people too, but we were tinkers living in a tent in the wood of Argyll. And of course we did a lot of good things forbyes, because we helped the old folk. My brothers and I sawed sticks and we collected blocks along the shore for their fires and we dug a few gardens. If there was a little job for a penny or two, we would do it for them. We did things for the people that the other children would not do. And we gained a good respect from some of the older folk where we lived. As the evening was over boys would get together, and we’d climb trees and do things, but we never caused any trouble or damage. But some of the people in the village actually hated us.

I went to the little primary school in Furnace when I was six years old. It was hard coming from a travelling family. You went to school with your bare feet wearing cast-off clothes from the local children that your mother had collected around the doors. And of course you sat there in the classroom and the parents of the children who were your little friends and your little pals in school had warned them, ‘Oh, don’t play with the tinker children. You might get beasts off them, you might get lice.’ You were hungry, very, very hungry in school. You couldn’t even listen to your school teacher talking to you, listen to her giving you lessons you were so hungry. But you knew after the school was over you had a great consolation. You were looking forward to one particular thing: you would go home, have any kind of little meal that your mother had to share with you, which was very small and meagre, but she shared it among the kids. Then you had the evening together with your granny and your parents. The stories sitting by the fire, Granny lighting her pipe and telling you all those wonderful stories. This was the most important thing, the highlight of your whole life.

We were the healthiest children in the whole village. We ran around with our bare feet. We lived on shellfish. We didn’t have the meals the village children had, no puddings or sweet things. We were lucky if we saw one single sweet in a week. But we hunted. If we didn’t have food, we had to look for it. And looking for food was stealing somebody’s vegetables from somebody’s garden or guddling trout in the river or getting shellfish from the sea. We had to provide for ourselves. Because we knew our parents couldn’t do it for us. Mammy tried her best to hawk the doors, but you couldn’t expect your mother to go to the hillside and kill you a hare or a rabbit. And you couldn’t expect your mammy to go and guddle trout. So, from the age of five-six-seven year old you became a person, you matured before you were even ten years old. And therefore you were qualified to help raise the rest of the little ones in the family circle. You could contribute. Because you knew otherwise you wouldn’t have it. You didn’t want to see your little brothers and sisters go hungry, so you went to gather sticks along the shore, sell them to an old woman and bring a shilling back to your mother.

The epidemic of diphtheria hit the school in 1941. Diphtheria then was deadly. Now you had to pay a doctor’s bill in these days. And by this time there were nine of us going to the single little school, all my brothers and sisters going together. But because there were so many children actually sick with diphtheria, they closed the primary school. Now we ran through the village with our bare feet. ‘Little raggiemuffins’ they called us in the village. Our little friends, five of them went off to hospital with diphtheria. Two of my little pals never came back.

My mother had good friends in the village, but some people wouldn’t even talk to us. One particular woman, a Mrs Campbell, had two little boys. She was one who wouldn’t even look at you if you passed her on the street. She wouldn’t give you a crust. After the school had been closed, I walked down to the village this one day in my bare feet. She stepped out of the little cottage.

And she said, ‘Hello, good morning.’ I was amazed that this woman should even speak to me. She said, ‘How are you?’

I said, ‘I’m fine, Mrs Campbell. I’m fine, really fine.’

She said, ‘Are you pleased? Are you enjoying the school closure?’

I said, ‘Well, the school’s closed. We’re doing wir best to enjoy wirsels.’

She said, ‘Are you hungry?’

I said, ‘Of course, I’m hungry. We’re always hungry. My mother cannae help us very much.’

She said, ‘Would you like something to eat?’ Now I didn’t know, I swear this is a true story, that her two little boys were took off with diphtheria and sent to Glasgow to hospital. She said, ‘Oh, I have some nice apples. Would you like some?’ Now an apple to me was a delight. She said, ‘Come in, don’t be afraid!’ And she brought me into that house for the first time in my life, into the little boy’s bedroom. And there was a plate sitting by his little bed full of apples. He was gone. And she took the apples from that plate and gave them to me, three of them. She said, ‘Eat you this, it’ll be good for you.’ I didn’t know what she was trying to do. Because I was too young, only thirteen. And she was trying to contaminate me with the diphtheria because her two little boys were taken away. Because none of Betsy Williamson’s children ever took diphtheria. And that school was closed for five weeks. And everyone was saying, ‘Oh, have you got a sore throat?’

Then they began to realise, why were the travelling children so healthy? And they used to say, when my mother walked round the doors of the village, ‘What was Betsy Williamson – oh, Betsy Williamson must have superior powers. She must be collecting herbs or something in the woods and looking after children.’ You see what I mean? And some would say, ‘Oh, she must be some kind of a witch.’ And things were never the same after that, never the same.

We were nine children going to school. But if you were a mother with only three, and you lost two with diphtheria; and your neighbour next to you, all her children survived, you would feel very, very envious. You’re going to feel very broken-hearted that some children should survive and some children should not. And that woman who gave me that apple, she never, never spoke to anyone again as long as she lived. Not even me, not my mother, nobody. She never spoke to anybody at all, she went kind of crazy out of her mind. She lost her two little boys and went completely crazy. Her man about four years later fell over the quarry and was killed. Some said he threw himself over.

When my brothers and sisters and I were in the school we had to stand torment from the children and static, the teacher saying we were little tinker children. She didn’t pay as much attention to us as she paid to the rest of the kids in school. We weren’t even second class. We were just there – she had to teach us because we were there. She couldn’t have cared a damn whether we were or not. But we did not stay off school. Some of the local kids stayed off, when they took flu and sneezes, colds. But even though we were not feeling very well and we were hungry, we still went to school. The only reason we went was to get 250 attendance marks, each of us, so that we could get away with our daddy and mammy for the summertime. We got two attendance marks per day, and we did about five months in school, from October through till February. The more we attended school, the sooner we could get away. Once our Daddy knew we had got our attendance quota, he knew we could take off. He burned the big barricade and packed up the few things which we children could carry. Each one of us carried something. And this is what we looked forward to all year. We weren’t interested in getting our education in school. Education began when we left school: hunting, guddling for trout, camping by the seaside, cooking shellfish and having a long summer to go with our parents, go hawking with our mother round the doors and going round the fields with our father cutting a little hay. It was an exciting time.

We travelled all Loch Fyneside, down to Lochgilphead, down to Tarbert, up Kilmichael Glassary, round by Oban. We had the time of our life. Father would get a little job in a farm and we put our tent in the field. In these days the fields were full of rabbits and the burns were full of trout. But one thing Father was against was the standing stones, the Pictish stones. We were allowed to look at them, admire them. But we could not even put a hand on them. He wouldn’t even let us touch them. We were not allowed. It was a belief that had passed down from his generation, from his parents as a kid; he was taught to leave these things alone.

But I didn’t believe my father, so I climbed one of the stones. Right up to the top of the standing stone. I sat there in the sun. The camp was beside the stone. He wouldn’t put the tent too close to it, just within looking distance, about thirty yards from the stone. He admired the stones himself. I’ve seen him standing there with his hands at his back for hours looking at that stone. What he had in his mind I wouldn’t know. Looking at it for hours on end, staring and imagining. But then I sat up on top. Oh, I was the king of the castle, you know!

He said to me, ‘Boy, would you come down off of there!’

I said, ‘Why, I’m no doing any harm!’

He said, ‘Come down off that stone at this moment or something bad’s going to happen to you.’ This was the month of June. It was a warm summer. Father was cutting a little hay with a scythe. ‘Come down from there, boy,’ he said, ‘at once! And don’t you ever try that again.’

But anyway, I obeyed his order and I came down from the stone. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘when I get my hands on you, I’m going to put my belt across your backside.’ So I was a wee bit afraid. I wandered away. And the young corn was coming up. I sat down in the corn, next to the field where we stayed. And then I must have lain down, because I got sleepy. And the sun came up . . . and I was sun struck. They searched far for me. They thought I had fallen in the River Add that passed by. They thought I was lost. They shouted and cried. But I heard nothing. I was struck with the sun. And for two long months, June and July . . . it was the beginning of August, time to leave and go back home to Furnace again, get the tent built up and get us back to school. But my mother hurled me in a little pram. I can’t remember that; she only told me later. I was completely lost for exactly two-and-a-half months. Struck with the sun, and I was about seven years old.

Then, just before we came home to Furnace my brothers George and Willie were catching gulls. They never hurt them, but caught the white gulls that flew around. They had a piece of bread on a string. They tied it and scattered bread all around. The gull would come down and swallow the piece of bread tied to the string. There were no hooks or anything, so it wouldn’t hurt them. As the gull swallowed the piece of bread, within seconds he pulled in the fishing line and caught it. You petted the bird, looked at it and then set it free.

So I was lying out there in a little pram my mother had for me. I couldn’t walk, was completely lost, brain burned out with the sun. My legs were paralysed. My father and mother blamed it on the standing stones, the curse of the standing stones. The boys were catching gulls, and I saw this gull with a piece of line in its mouth. My two brothers were pulling the gull in, nothing to hurt it, pulling . . . And I opened my eyes. I looked up and saw them catching this gull. Pulling it in, and that’s when I came back to my senses. After two long months. George was two years older than me, Willie was two years older than George. Nine and eleven they were.

Father had said, ‘These stones belong to your people, your people a long time ago. They put them there for a purpose, so that you would remember them. These stones are there for you to remember your people by, not to deface them, not to climb them, not to touch or do anything on them. Respect and love them, that’s what the standing stones are for.’ And Father would always make sure he would camp not far from some of the great standing stones. He would have no fear of burkers, no fear of ghosts or spirits that many people had in these days. He felt safe, as if that giant stone were looking over, guarding us children. The stone was looking over us. In the summer. And we always went back to the same place in the summertime.

Years later I was to spend time under the Pictish cairns by myself. But it was the lesson Father had said to us, ‘They’ll never hurt you, they’ll never touch you. Leave them alone, they will guard you, you will feel no fear. You won’t be afraid.’ Respect and love for these stones had been taught to him down through the ages. It was magical.

The end of October, that’s harvest time. Father would finish the corn cutting, and that’s when we went back to school. We came back a week before the end of the October holiday. You had to build the barricade tent, help Daddy get the sapling boughs for the frame, patch the covers, collect stones for the base to hold the covers tight. We had to build a winter home for ourselves in the wood. And Father needed all the help he could get. We had to go to another wood, cut saplings, build the barricade all over again. He couldn’t do it on his own. It took two weeks, and we came home in the middle of October. He knew once he had the tent up and everything fit for us, then we could go back to school.

He said, ‘Now, weans, it’s up to yourself. If you want a holiday next summer . . .’ I remember getting up in the mornings in winter. Mother and Father lying sleeping in their bed and we going to the burn, washing our faces, with our bare feet. No tea, no breakfast, nothing and we went to school. All because we needed that 250 attendance. But my daddy and mammy knew they were giving us an education we were never going to get in school, because they knew we were never going to go off to any high school or things like that. They knew what they were teaching us was going to stand us good in our lives to come. Now we could leave home: I ran away from home first when I was thirteen and by the things I learned travelling with my father and mother around Lochgilphead, I was able to cope with my life. I knew the farmers, I knew how to work on the farms, I knew how to cut peats. If I hadn’t done that 250 attendance in school, I would never have got the experience – freedom to learn from my parents.

But there was also the law that children were taken away from their parents if they did not attend school. If we had left school without the 250 attendance, we would have been arrested. It was law. The School Board would have come along, the Cruelty Inspector.

He said, ‘Have your children been in school?’

If Father had said, ‘No, they’ve never been in school.’

‘Okay, then, just a moment.’ The Inspector walked to the first old traditional phone box. He phoned up a taxi. And then you were gone! You never saw your parents again, never. There were hundreds of children taken off, some went to Australia, some to Canada, some went around the world, no one ever saw them again. And parents were never informed. They were taken to Industrial Day Schools – not only traveller children. But they were worse against the travelling children. If you were in a settled community you would be able to attend school some days in the weeks through all the school terms. But the travelling people travelled to find work, and never sent their children to school most months of the year. And anyone over the age of five without the attendance quota was taken off – you never saw them again. I had cousins who were taken away, whom I never saw again. My Aunt Nellie’s lassies.

Well, my father loved and respected his children, and he wanted to teach us to grow up to be natural human beings, learn the basic things of life he had learned as a child. He taught us about the standing stones, how to work in the fields, and gather stones. Oh, he couldn’t read or write himself, and he wanted us to be able to have these skills. But the teacher couldn’t care less whether we learned to write or read. And we didn’t wait till the school broke for a holiday. Once we got the attendance quota, we were off! Sometimes it was March, sometimes February. And this was the basic thing; Father knew the moment he took us off the school, we learned how to put up a tent, how to pick good dry grasses for our beds, how to gather firewood. When he got a little job, we went along and helped him with it. All the kids went and helped their parents every way; girls went with their mammies hawking round the doors.

We used to go up in the hills. Well, there’s a shortcut that takes you from Minard over the hill to Kilmichael Glassary, a twelve mile cross. And there in the middle of the hill is a sheep farm known as the Tunns. Old Duncan Stewart and his brother Hendry and sister Annie owned the farm. And we stayed there for a week, sometimes a fortnight. Mammy scrubbed the stairs and Daddy helped with the hay, cutting it with a scythe and building up little stacks. The Stewarts kept a couple of cows, and they had mostly sheep. And we would have the time of our life! There were fruit trees in the garden, and we cleaned old Annie’s garden. And she would bring us each big bowls of porridge. We slept in the byre, sometimes if the nights were cold. And she would sit there and milk the cow in the morning, ‘zing, zing, zing’ into the zinc pail, us lying in the stall among the straw, warm as pies, you know what I mean! And the big River Add ran beside us. We could guddle trout or poach an odd salmon. Daddy would dig the garden, cut the hay and trim the trees. He clipped the sheep with old Duncan and Hendry. Mammy scrubbed the kitchen floor. And they looked forward to this!

Old Annie would say, ‘Och, Betsy will soon be coming.’ And Annie Stewart kept a diary on every child that my mother had. And the sad thing was, even though Annie loved us all, Mother never called one of her children after her. And she always wanted one of Betsy’s kids to be called after her, old Annie Stewart. Mother called the children Susan, after another farmer’s wife, and Nellie, after someone else. But never ‘Annie’. Annie was her dearest friend. And Annie always looked forward to Betsy coming in the spring to clean the stairs and scrub the landing, help to clean up the kitchen and things like that. Because in these days things were really rough. It was a sheep farm away out in the countryside. And of course Hendry and Duncan waited until my father came before they started clipping the sheep. He helped them because he was a great clipper himself, rolling the wool, bagging it and doing all these things. But we never caused any problems around the farm, no way in this world.

It was a highlight for us visiting the farm, but it was always a highlight for them! Mother gave them the news. Because it was eight miles to Minard. Mother walked round the doors of the villages with her basket and she would talk to Mrs MacVicar or Mrs such-and-such and say, ‘Somebody’s ill’, and ‘somebody’s died’ and ‘the gamekeeper this’ and everything. She would bring the news to Annie. And she and Father would sit in the kitchen, have a wee drink together. They would have a wee talk and a wee ceilidh.

Mother would tell the news about Lochgilphead and Loch Fyneside.