Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

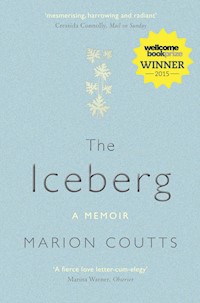

THE WINNER OF THE 2015 WELLCOME BOOK PRIZE SHORTLISTED FOR THE SAMUEL JOHNSON PRIZE, 2014 SHORTLISTED FOR THE COSTA BOOK AWARDS, 2014 (BIOGRAPHY / MEMOIR CATEGORY) SHORTLISTED FOR THE DUFF COOPER PRIZE LONGLISTED FOR THE GUARDIAN FIRST BOOK AWARD, 2014 In 2008 the art critic Tom Lubbock was diagnosed with a brain tumour. The tumour was located in the area controlling speech and language, and would eventually rob him of the ability to speak. He died early in 2011. Marion Coutts was his wife. In short bursts of beautiful, textured prose, Coutts describes the eighteen months leading up to her partner's death. This book is an account of a family unit, man, woman, young child, under assault, and how the three of them fought to keep it intact. Written with extraordinary narrative force and power, The Iceberg is almost shocking in its rawness. It charts the deterioration of Tom's speech even as it records the developing language of his child. Fury, selfishness, grief, indignity and impotence are all examined and brought to light. Yet out of this comes a rare story about belonging, an 'adventure of being and dying'. This book is a celebration of each other, friends, family, art, work, love and language.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Let It Go

It is this deep blankness is the real thing strange.

The more things happen to you the more you can’t

Tell or remember even what they were.

The contradictions cover such a range.

The talk would talk and go so far aslant.

You don’t want madhouse and the whole thing there.

– William Empson

Contents

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

Section 4

A Note on the Author

SECTION 1

1.1

A book about the future must be written in advance. Later I won’t have the energy to speak. So I will do it now.

The others are near. I can touch them, call them to me and they are here. We are all here, Tom, my husband, and Ev, our child. Tom is his real name and Ev is not really called Ev but Ev means him. He is eighteen months old and still so fluid that to identify him is futile. We will all be changed by this. He the most.

The home is the arena for our tri-part drama: the set for everything that occurs in the main. We go out, in fact all the time, yet this is where we are most relaxed. This is the place where you will find us most ourselves.

Something has happened. A piece of news. We have had a diagnosis that has the status of an event. The news makes a rupture with what went before: clean, complete and total save in one respect. It seems that after the event, the decision we make is to remain. Our unit stands. This alone will not save us but whenever we look, it is the case. The decision is joint and tacit and I am surprised to realise this. Though we talked about countless things – talk is all we ever do – we did not address it directly. So not a decision then, more a mode, arrived at together.

The news is given verbally. We learn something. We are mortal. You might say you know this but you don’t. The news falls neatly between one moment and another. You would not think there was a gap for such a thing. You would not think there was room. The threat has two aspects: a current fact and an obscure outcome – the manifestation of the fact. The first is immediate and the second talks of duration. The fact has coherent force and nothing, no person or thought or thing, escapes its shift. It is as if a new physical law has been described for us bespoke: absolute as all the others are, yet terrifyingly casual. It is a law of perception. It says, You will lose everything that catches your eye. Under this illumination there is no downtime and no off-gaze. For its duration, looking can never be idle. Seeing is active: it is an action like aiming or hitting.

Yet afterwards – more strangeness – we carry on in many ways as before, but crosswise to what might be expected, we are not plunged into night. It is still day, but the light is unnatural. The glare on daily life is blinding. Everything is equally illumined, without shade.

These are early days. Our house becomes porous. I am high and bleached and whited out. We are air and the walls are air. On hearing the news, our instinct is to tell it. Once known it cannot be unlearned; once told, not rescinded. So we start to speak, and the family, we three, are dissolved in fluid and drunk up by others. People appear, they come and go. They are always to hand. Ev is in his element and we are in ours. As I say, these are early days. Maybe it will always be like this.

1.2

It is Ev’s first day at the childminder’s. I arrive at nine, anxious and grave and trying not to show it. This is our first official separation. The mother of one is a volatile mix of niche knowledge and inexperience. I am a zealot. I have rolls of data to proclaim about his protocols: his beaker, when he likes to nap, his poo, his play, his pleasures, the snacks that are allowed and the snacks that are forbidden. I am not going to let anything stop me.

The childminder lives around the corner. She is much younger than me and canny. She has heard all this before. She knows to be patient and let me play myself out. When I am done, she will take the child. I eye her up and scan the house for flaws as I recite my speech. Is that a very sharp edge? That stair-gate looks shaky. The kitchen could be tidier. I know she has dogs; where are they? Why am I putting him in a house with dogs? We both understand that my rhetoric is symbolic, the words a verse-chorus lament to mark the movement of the child out of my orbit and into another: out of the home and into the world.

In mid-song I am interrupted. Tom arrives. I am surprised to see him and pleased. Lately we have been seriously upended. A week ago, while we were staying at the house of friends, he had a fit. We don’t know why. He never had one before and the shock took us straight into hospital in the night. In the wake of this we have been unnerved, though slowly calming as he has been fine since and anyway, there is Ev to think about. Soon we expect some test results from the hospital. I imagine a letter about high blood pressure or diet, some readily managed condition, normal, nothing beyond us, nothing outwith the stretch of mid-life or span of circumstance. If you were to ask me, that’s what I would say. But really I am not imagining anything. I am thinking about Ev.

Tom greets me directly and takes my sleeve, pulling Ev and me out of the yard away from the toys and into the street. It’s good he is here. He recognises the importance of my mission and is come in solidarity to support me. I am an airship on its maiden voyage packed with mother adrenalin. The band is playing. Ascent is the most dangerous moment. I have already left the ground, my skin taut with the child and his real and imagined needs. The three of us cluster a couple of doors down alongside a white house with a low lilac wall. Number 36. Alpines, succulents and tiny sedum rooted in the shallowest scattering of earth are planted in gaps along its brickwork. Ev wriggles in my arms and I am still talking. Ev is so relaxed. He likes her. He will be happy here. Tom stops me. He says he has had a phone call. He has a brain tumour. It is very likely malignant.

Did I understand it before I heard it or did he finish the sentence before I understood? Conflagration: my ship is exploded. A fireball. Tears fall as burning fuel. There is no time for anything to be saved. There is no time for anything to sink in. There is no time. The word is the deed. The deed is done before knowledge can release its meaning. It is the quickest poison.

I am crushing Ev and my crying escalates. When did it start – before, or after? I don’t understand. It seems I was crying before I heard it. Ev starts to wail and this brings the childminder on to the street and frightens the other child in her care, Ev’s new friend-in-waiting. He runs to the gate and looks at us blankly. What are they doing? The ceremony is over. Ev’s rite of passage is abandoned. Tom gives him into the arms of a stranger and we flee.

Did I go back and pick him up at four? I don’t remember how he came home but somehow at the end of the day he is back with us. By his face I see he is content in the new world he has inherited so precipitately: dogs, children, a yard outside to play in, plastic toys stained with rain. It is strange. He is entirely unblemished. Not a mark on him. He is unharmed, happy even. When we left the house that morning we were blithe. We were not conscious of death. We knew it existed, but not for us.

That day, the first near-coherent thing I say after many hours is to Tom. I cannot lose all of you to all of him. I will not.

Right from the start see how I set myself up. Let us see how this thing goes.

1.3

The day of the diagnosis delivered by phone we abandon Ev and start walking. Impact has fused us and made us mutual. We are a four-legged creature and we operate manually. Our instinct is to keep in motion. We head south. We talk, but we don’t look at anything. The suburbs are good for this kind of inattentiveness. This is what they are for.

After some hours we arrive at Dulwich Picture Gallery. We did not aim to come here and I don’t know where else we have been. But now that we are here, Tom needs to look at a painting. When the phone call came he was in the middle of something and there is a picture he wants to look at. Though we both try to recall it, we never again remember which. Perhaps this is the first thing to be noted. That time is continuous. For him the action of looking at a picture is instinctive. It is his work and so familiar, so unremarkable an action that only much later do I wonder at it. There is a particular painting still to be considered. Time hasn’t stopped even now. But it spools new. I can feel it – not faster, not slower but with an undertone, a tiny subjective pulse.

Tom’s mind is busy. He has a brain tumour but he still has a mind. Where is his mind? Where it was this morning. The brain tumour is in it but the brain tumour is not it. Yesterday and the day before, the day before that, and all the days for however long since, the tumour was already there but we did not know. A thing first hidden in the site of consciousness later becomes knowledge.

We are novices. We have very little information and so repeat what we have. One phrase goes back and forth between us. The tumour is in the area of speech and language. The tumour is in the area of speech and language. There is tumour and there is area. They sound separate, like two entities, one collaged on the other. I do not consider the idea that the tumour might one day take the mind. That thought comes later. Mind trumps tumour. Art trumps everything. Tom goes into the gallery.

In blankness of mind I remain outside. In the garden is a skeletal cypress, blanched sepia and white as if struck by lightning and still erect in its death agony. I stretch out on the grass under this tree and look straight along its length to the point of sky touched by its tip as if it might be showing me something. Some time elapses that I can’t describe at all and I am still there when he returns.

Four days later, Ev starts to talk. His sounds have been buffering at meaning for weeks, but now they emerge as his own handiwork and he sets them gently one beside another in lines. I am surprised by this development but everything in this time is unfamiliar: other people, preparing meals, the view outside the window, the first thought in the morning when I wake, Ev’s face. It is all something I must get used to, and so his talking is just another thing that has occurred that runs along in parallel to the main.

Children are born into language. They understand the nuances of speech at birth and Ev has been listening to our ceaseless chatter for months in the womb. He has been read to and sung to and laughed at. He knows the pattern of our voices and by its cadence he knows too that something is happening. My face signals it, and the sudden sparks of urgent conversation, the gaps that follow. Ev is spared the violence of knowledge but all the rest he experiences with us. We will learn to be articulate about this together. We are at the beginning.

The impact on our house feels physical. It is as if we have reconfigured the internal architecture or moved the position of the house subtly by degrees with respect to the sun so that the light falls oddly within it. But in the midst of this derangement, Ev’s vocabulary as he presents it to us is superlatively normal. He has no words for fear. He says Daddy to mean either of us, kee for monkey and Oh no! at all upsets. Ssss serves for snake, the letter S, and any linear thing like a belt or bit of his railway track. He says click for light and sta for monster, gakator for tractor and soon has a small handy clip of words like digger, apple, spoon, butter, cardi, eye, toast, brush. Seem means machine. He can do two, three and four.

And in a way that is entirely normal too, we poke him and spur him on. This is what you do with children, goad them for your own enjoyment. Make a noise like a volcano, we say. Make a noise like a firework. Make a noise like a dinosaur. His eyes are merry. A small, sweet, plosive sound comes from his lips, after each entreaty the same noise, a breath out and a consonant mixed with spit.

1.4

It is my birthday. One week on. We go to a restaurant and take a table in the sun. Radiant September. When they are very young we do not regard our children with much clarity at the best of times and at the table I can scarcely fix Ev in my sight. He is the size of a cat; a thing of gold fur and whitened sunshine. His hands paw and pat the textures of the food as he draws each substance one by one into his mouth: sour, sweet, char, salt, pulp, oil and leaf. It is thrilling to sit with him so grown up. We are here to mark my birthday and something else besides. We make a toast, the least frivolous I will ever make.

To us. To the time that is to come.

When we get home Moses turns up to deliver the sofa. We ordered it from his shop before the diagnosis and here it is after. We can’t say no, though it is ridiculous. A second-hand sofa? No, it wasn’t us. Regime change. All deals are void. Keep the money but take it away please. But here he is manoeuvring it up the stairs before we can do anything about it. We have guests and five of us sit flattened, glasses in hand, on the other two sofas in the room where it is to go. When Moses sets it down, it looks as if it has always been here. We decide that it may stay. More guests can come to sit shiva. It will make room for more sitters.

1.5

To make sense of what is happening, we need to say it aloud. Only then will we hear the news mouthed back by others and reshaped into words – ohs and ahs, expletives, hisses, clicks and long out-breaths. Maybe, coming back to us in this way it will sound different; better, worse, I don’t know. Maybe more comprehensible.

So this is what we do. We make an email list of our friends. Concentrating is hard and even remembering who these people are is an effort. We go back to the things we know, the building blocks of our past. Our wedding was nine years ago and at the heart of the list are the wedding guests. We liked these people then and mainly we like them still. Slotted on are new friends met since, lists from subsequent parties, lone figures and friends from more recent, interlocking spheres of the social. We do not edit but add. It is construction work and we are going for solidity: mass, weight and number. Some, who provide their own reason and context or inhabit a singular niche unconnected to the rest by profession or inclination, get left off at first by accident. How on earth did we forget them? We are aware that new friends might be made and added, though it feels fraudulent to make friends who know us only in our changed state. We should whisper, This is not who we really are. The list is a net: personal, professional, loves and links, close and near, from getting warmer to very hot. Family is here too. Their names are on the computer: itemised, digitised and alphabetical. Now is their hour.

So far only a few people know. The first thing to understand is that endless retelling is overwhelming. It is boring, draining, dispiriting. A tumour is hard to speak of and harder still to hear. I don’t have anything else to talk about, but even after the first few attempts, my words sound dulled. It makes a poor recitation. Everyone who hears us wants all the details and the details will be the same: a fit – hospital – a scan – a tumour – cancer – surgery – treatment – uncertainty. The framing of the sequence can be stressed to suit different audiences or the whole might need retelling again from the beginning. Hearing can be veiled by not listening. And our friends and families have their own responses that must be attended to. That is our responsibility. We owe them. We don’t want to overburden them or frighten them off. This is our disaster. They are just being called upon to witness.

And where does the stress lie? We don’t know. The facts are not many – surgery followed by radiotherapy followed by chemo followed by monitoring. The way the facts fall depends on how you tell it. Is it a story of disaster directly or a version of survival? What route does it take? Is it a story of duration? We don’t want to give people the wrong idea but what is the idea? The thing is an ugly knot of accuracy and projection, dead weight and measured hope. Tied up in there somewhere are the statistics. Tom is beginning to describe it. I can barely speak. So together we write them a message in the form of an email.

14 September 2008

Dear Friends

We have some troubling news that you should know. A small tumour has been detected in Tom’s brain. It’s not known yet whether it is malignant but that is possible. It needs taking out and he’ll be operated on in about a week.

We don’t know yet what any of this means, in terms of further problems or none, or possible side effects from the operation. It’s a very uncertain time for us.

After the first shock, we are strong as we can be. This is largely because Tom is at the moment very well, looks well, is lucid, thoughtful, writing, working, preparing. Ev is fabulous as usual.

At the time of the operation and after, we may need some help. We don’t know yet what form this might best take, it could be practical, or just to have our friends in contact, to be phoned up, thought of, emailed, visited.

We will let you know when we have a date for Tom going into hospital.

With love

In the study we bend over the computer, tight under the lamp. Tom presses Send. It is serious, this action. By agreeing to its terms and conditions we elect to turn everything pertaining to us a different shade. Once the news has gone out we cannot disavow it or pretend it is not happening. I cannot say I am prepared. I don’t have a coherent idea what Send means.

I don’t have to wait. Messages come back immediately. What were they doing, these people? All hunched over screens so late at night, at home, at work, as if primed and ready to consider Tom’s brain? News, News, News, News: the word scrolls down in bold text, multiplying in the subject box like a black manifesto printing over and over. Now we are visible. We can be found. The sky has rolled back, revealing the perpetual plains below ceding into darkness. We are isolated and illuminated. From a distance, I can look into our house and see the small family inside it. How easily we may be overrun! How defenceless we are! It is pitiful.

At first, before I understand how it works, I analyse the replies forensically, sifting the words and weighing them. I am searching for signs. It is the most basic superstition, like reading tea-leaves or looking for pictures in a fire. I make instant judgements based on how the words fall and I react in proportion to how dear I hold the friendship. How much do you love us? Do you know us really? How canyou protect us? I cannot help myself. I might easily hate those who fall short or whose response is lacking. We are in mortal danger and we want to bring our people near, to gather and shield us, stroke us and sing to us. Isolation is death. We will be picked off. That is certain. But email is too crude for divination. The little fonts in stubby lines cannot take it. Words merge and swim about, scarcely readable. Quickly, mercifully the judgements fall away. I have it wrong! This is not about us but about them. We are simply refracted and talked about at second-hand.

There are no rehearsals for these responses. Some have had prior experience in death but whatever they do with us is a first take. All must improvise. Some talk firmly about themselves in long and looping, myopic paragraphs. Some remit their love directly. Some are blessedly, seriously practical. Some are brilliant: full of anecdote and funny. Most are short and this is cleverest. Some come out wrong, missing a connection of word or tone, like an unfinished puzzle or an arrow fired off into a hedge. There are straight-up reminiscences, protestations of love and notes on shock. There are brief, businesslike missives. Thank you for keeping me informed – this is perfect and suits very well the sender, like a pair of smart breeches or brogues. Some are hapless. Some do not reply at all and nor do we think less of them. Sending is all and lack of response never deletes them. This is not a group from which you unsubscribe.

We get poems and photos, links to sites, mad advice, offers of dinner, invites, suggestions, jokes, clichés and generosities. Courage in all its forms, liquid and solid, is pressed upon us, pressed and patted, poured and shaped to suit us. But over and above the offers of help and love, precious and determined though they are, is the fact that we are public knowledge. Our signal has been heard. By each response a friend is activated. Our message had a single note. Here is its returning chord.

It goes without saying that I am crying all through this time, except in front of Ev, before whom there seems to be nothing to cry about.

1.6

A new future has been handed to us. Now that it is here, it is impossible to recall what we were expecting before. Ev was born eighteen months ago, so it would have been a lot. But there is no question. The exact texture of past desires cannot be recalled. It is gone.

Ev made more sense to me before as part of a continuum. I study him. He is evident, but the memory of his birth and the circumstances of him coming into being are not. I am reminded that he was born by emergency caesarean. Like a piece of magnetic tape he self-erases neatly. Ever-replacing, refreshing and renewing, he grows older. In the new future, he is coming with us.

Eighteen months later here we are again. It is the same hospital and the schedule of the new future is written on its headed notepaper. Brain surgery as fast as it can be booked, followed by combined chemoand radiotherapy for the six weeks until Christmas. The chemo is called temozolomide. Six months’ more chemo in twenty-eight-day cycles will swallow up the first half of next year, the whole long arc comprising just one round of treatment, one line of attack against the tumour. Each stage will follow the previous one unless we decide to abandon and bail out. It is voluntary. We could do it at any time. But we do not, we sign up.

Tom feels extremely well. Energised by the attention. The surgery is upon us soon, so in the month between diagnosis and operation he and I lose weight. It is best not be overweight for brain surgery and I do it in straight physical alliance. Like giving up smoking, it’s easier with two. The kitchen is where we spend much of our time at home and cooking and eating together is both the maintenance and decoration of our days. To differentiate ourselves now would be unthinkable.

I do not have what are called food issues. In normal life I do not weigh myself. I do not have what are called body issues. Mainly I think I look good. I know this might be seen as strange for a western female in her forties but this is one of the points on which I differ from the norm. I don’t diet. I don’t restrict my intake. I am a size 10 or 12 depending on who is manufacturing. Weight is not something I spend time on.

Tom is much heavier than me. He has two issues around food, or three. He likes it. He is greedy. He eats too much. His diet in the past has been more extreme than mine. In his twenties he would eat Vesta ready-meals. He has eaten at KFC. Of his own volition he would buy a coronation chicken sandwich. I would never do this. His formative food experiences were parlous: an elite public school in the 1970s, forced to eat eggs, both yolk and white, and sauces and slop as was the English way, milk puddings and gammon. Fricassee.

I take charge of the shedding of weight. Here is an area of authority that can be mine. I am focused but not mad and our kitchen diktats are basic and sensible, the ones that everyone really knows. In the kitchen I can expand my theories and believe in their efficacy. Working with colour and smell and taste I will make food that is delicious. In impotence, here is something I can actually do. It is a form of control.

As a new convert I am an extremist and at first my cooking is gross. Leaving fat and pig and seasoning all aside, I make vegetable stews strained of taste and colour. But quickly, it all becomes strangely viable. Small plates, small plates, is the new mantra. I will write a diet book with just this theme. People write books with fewer ideas. It would need padding with cod-science, recipes, edicts, praise, colour photographs and homilies, but basically it would be saying: learn to cook, food you like, not fried, plates 8 cm diameter, not piled high. And don’t come back for seconds. On the back of the book there would be an 8 cm dotted line template of a plate to cut out. Remember – don’t pile so high so that the food slides off! That should make it clear enough. But then I might have to mention cancer.

Everyone should eat off side-plates. Ours are melamine, a set handed down from my grandmother in off-kilter, food-referent colours: mushroom, aubergine and turmeric plus a cracking kingfisher blue. No salt, no bread, no fat, no dairy, no seconds. This is written on a Post-it note on the fridge. But neither is the word No an absolute. We don’t like absolutes. We eat well. The last one, no seconds, seems to be key.

We have less than a month before the craniotomy and we get thin fast. People keep coming up to Tom having heard he has cancer and saying But you look so well. This makes him laugh. What they mean is, You are thin! Well is the euphemism of choice. I head straight for eight stone. One night in the gloom of a restaurant my armpits look like white caverns in the sockets of my dress. I only feel really hungry, dizzy-hungry, once, and that was a clear marker. We must eat. And so we do.

Ev is on another track heading in the opposite direction. He goes at food with intellectual interest and straight joy in taste. It is bonny. If I had known how much pleasure I would get from watching my baby eat I would have thought it an argument for more babies. It is such a treat I can’t take my eyes off him and I mask my keenness in case it makes him suspicious that there is something more at stake. So I eat with him, or look out the window or pretend to read the paper. He spoons up lentils, snuffles through tomato sauce with basil and surges his pasta round in it, he dips bread in spinach soup till soup and bread are one and sucks it. He holds broccoli like a cudgel and stuffs one, then two, three, four trees into his mouth. He eats liver! He eats bananas and garlic and stir-fry! We goggle at him. We win and he wins. We all triumph together.

All this differential feeding, fat and lean, exists side by side in the same kitchen. It takes organisation and the organisation is down to me. It comes at a cost: of time, focus, not doing much else apart from the barest bones of my work. But then nothing much else is getting done anyway. Everything is at a cost now. Roasting a sweet potato is priceless. Baking fish in foil is an elevated act. To eat is to partake in the grace. And what could be sweeter than feeding those you love?

1.7

25 September 2008

Dear Friends

Some further news about Tom. He’s due to go into hospital on 29 September to have the tumour in his brain removed. He will be in the National Neurological Hospital at Queen Square. The operation will be on the Tuesday. All going well, he should be home by the end of the week.

At the moment nothing can be predicted in terms of recuperation and further treatment. But it’s important to us at this time that our friends stay in contact, so please do phone, text, email, visit, and so on, in the coming weeks. If we don’t always get back to you at once, don’t worry. We hope to see you soon.

With love

Before dawn on the morning of Tom’s operation we make a mistake. We have met the surgeon, Mr K, and he is confident, so we are confident. We trust, but we do not know. The consequences are opaque in all this. So we decide to bring Ev into the hospital. As benediction and blessing, all three of us will be present momentarily, like a single stable entity, a stool or tripod. Tom must not go off alone.

It is very early, directly continuous with night. When we arrive, Tom’s face has been mapped with marker pen circles and crosses. Thick stickers of green foam dot his cheekbones, temples and forehead. The markers will guide the computer to gauge the entry. The circles are to cross-reference the location of the tumour and point the lie of the head. On the surgeon’s table a head is a still-life object, like a cabbage or a clay pot in a painting by Zurbarán, picked out in light against darkness. It must not move.

Tom looks high and mad. He is present but not with us. We cannot make this work or laugh it off as funny face paint. Ev hates face paint, refuses it always. Even without the stickers and the black arrows, Tom’s eyes would betray him. Their daylight blue has been tamped into a thicker colour, studded with points of light that glitter in the warm half-dark of the ward. This is brain surgery. We are at altitude and we haven’t enough air. Not everyone gets to do this. We are celebrants to this fact. It is strangely festive.

Tom is Nil by mouth so as breakfast gets under way we go into a small guest room. A plaque marked with a picture and a date seven years ago names the room in memory of the donor who went this way before. I have brought Ev’s yoghurt and fruit mixed in a pot, his pink spoon. Tom tries to feed him but he won’t eat. Stupid. Why would he eat? I cannot eat. Tom cannot eat.

It is quiet. No one disturbs us. We could just run away, get the bus and go home or hide out somewhere else. That is the odd thing about hospitals. If you are mobile and have autonomy you can just run. I wonder how many do? If only we could. Belief holds us here; belief in technology, systems, institutions, in the whole apparatus of advanced Western Medicine. We are taking a bet and our belief is that this is the best bet. We stay.

The room is a place for patients to be private and receive guests but there is nowhere to sit and it is full. It has likely been a storeroom since shortly after the plaque went up. Hospitals abhor a void and all good intentions operate against entropy. Excess chairs are piled against the walls and the interior is navigated through stacked tables, wheelchairs, a zimmer frame, a nest of buckets. A noticeboard with nothing on it hangs near the door. Guests seek comfort elsewhere. Here there is none. The lighting is ranged in fierce strips on polystyrene tiles and the walls are two-tone beige separated by a peeling dado. An intense rectangle of back-lit sky at the window affirms that night is on its way into morning. We are getting near.

Ev is frightened. He squirms in Tom’s arms. It was a bad idea to bring him. He smells fear on my skin. Is Tom afraid? It doesn’t seem so. He is the chosen one, in a solo dream that ends where he does and goes no further. We cannot penetrate it. What are we doing here? Marking the interval between something bad that has happened and something bad that may yet happen. We are always marking things. It is our habit. But we could spend every minute of every day marking and it would never be enough. These daily acknowledgements always have the same aim – like the ill-lit photographs I take today – to achieve permanence, to fix ourselves fast in each other’s eyes. With Ev changing from day to day, this is wilful. Still we try.

We are three. The consciousness of one of us is being interrupted. His self-hood is in jeopardy. How will he be? Will he still be mine? What about knowledge of love? That’s the main thing. Where does love lie in the brain? Is it marked with a black cross? Will Tom love me and love the boy like he loves us now? If he cannot, how will that affect my love and the boy’s love for him?

I don’t want to stay though I am afraid of what will happen after we go. Time versus resistance seems an equation for stasis but strangely stasis is not what we have but something else, some other kind of empirical motion. We have brought Ev right into the heart of it and he resists to the full. He knows there is nothing for him here. But some improvised ceremony is called for, and this is it, held among the ramparts of spare furniture. It is now 7 a.m. on a Tuesday in early autumn. Soon I must leave. Soon I must take Ev away. I am not being given a chance to get used to this.

1.8

Tom is having a craniotomy. We who can’t be of any assistance here can only lower our eyes and walk the streets like penitents until it is done. After his broken benediction at the hospital I drop Ev at the childminder’s. Normality is his best respite. The early light has morphed into a seamless, gunmetal grey that seals the sky from edge to edge. I go back to the hospital without him. Vivien will be my companion but I am destitute, homeless and bodiless. I haven’t got this organised, what to do while waiting for the outcome of my husband’s brain surgery. There is no protocol. I can do whatever I like.

What I like is to be near. So we decide to stay close, never far from the hospital walls. It is a new attachment. I don’t know this area. The neurological hospital is in a part of London I’ve never had reason to cross, and through a narrow passage off Southampton Row just below the square runs a queer alternative grid of parallel streets. Under different circumstances perhaps I might have discovered it, as it seems to have a range of offerings. The Adult Ed Centre provides courses and big plates of strong dinner. There are gardens for office workers and invalids. Lamb’s Conduit Street has a well-heeled mix of bespoke suits, esoteric bag shops, high-end delis, coffee and books. If it were Ev who was sick, I would know the area more than enough. Great Ormond Street is next door.

For something to do I buy a scarf to curb my shivering and hold my coat shut against the wet. I choose it like a lady’s favour from a bin of coloured woollens. This one, to be worn on the neck in honour of the day. It is a soft, very pale blue. With it laid against my green coat I am the brightest thing in my vision. Everything else is wet ash. We have no agenda but to wait. We try to go to the bookshop to be indoors and have tea but I cannot sit so tame among the other drinkers so we leave. Around the corner is Coram’s Fields. I picture Coram as I learned about him at school, a progressive thinker, energetic in breeches, red face, white shirt and wig. The board on the gate says No adults unaccompanied by minors. Such a radical idea. We have entered childless but the spirit of Ev is fully with me and no one is here to stop us. This is because it is pouring: a full London pelt. We take cover in the stone gazebo and sit tight, framed by its columns in formal misery. Damp seeps into my legs. Outside the semicircle of our shelter the rain rebounds a foot high above the paving.

After a time, a decent interval as judged by a layman for the cutting and sewing up of the head, we return to the hospital. My scarf has stopped working and I am shaking hard. I leave Vivien on the stairs and as I walk to the door of the Recovery Room I hear a voice. Tom: a man chatting, not even with difficulty but just as exact, as excited as ever, his voice boomy and familiar, and this is a moment like no other. What is it like? Like more than the sum of all the things I have ever anticipated. More. My treat. My gift. Whatever else happens, there will have been this.

The swing door bursts out like a big hello and Mr K, the surgeon, is before me. His eyes fire up to see me and as we conference in the doorway he holds the door ajar with his foot. Water drips from my hair on to my face, from my coat on to the floor and pools around my boots. Mr K is very happy with it. Tom is very happy with it. I am very happy with it.

1.9

Twenty-two thick staples of metal run from below the jaw-line up into the shaved area behind the ear on the left side. From the front you notice nothing, but from the side a blooded silverine line fringed with scabs marks out a wound measuring 12 cm. One week after the operation it has healed well, with no trouble. We have been called back to the hospital to take the metal out and to hear the result of the biopsy. The biopsy is the moment we must submit to, I know that. The result will take us forward in whatever way we go forward but just now the situation with the staples is preoccupying me. The staples are getting in the way. We lean against each other on a pair of green chairs by the entrance to the ward and wait.

There is a machine to do this unpicking and it’s a simple tool from a kit a carpet-layer would use. From where we sit, crossways to the bed bays, we can see that there are only two nurses on duty, the German nurse and the one called Donna. Donna has been at various times the nurse assigned to Tom and the relationship has not been good. She is easily embarrassed, whether by him or by every patient she sees, there is no way of telling. It seems unfortunate, cruel somehow on her that she has elected to be a nurse. Her character might come over better as something else, although I’m not sure where her talents lie. She is readily flustered. Items get dropped: urine, blood samples, swabs.

Donna is self-conscious about her body in motion as if aware that she does not do the work well. To cover for this she moves slightly too fast, ever exiting the latest incident. She has been known to pretend not to hear. Her hair is distressed and blonde and fixed up at the back with a stabbed mass of Kirby grips. If she could see herself from behind she would not wear her hair like this.

The choice today is between Donna and the German nurse and whoever is free first will be assigned to Tom. Having watched Donna at work, the idea of her unregulated hands on the hardware to unpin his head makes me hot and weak. I want to cry. I have to stop her.

Charlie the charge nurse comes in. We saw him once in civvies in the lobby, dressed in battered shades of brown and grey and carrying a plastic bag. He looked like a man in a pub. His face is deeply lined, a current or ex-smoker, and in a bar you would not notice him at all. But on the ward he is the only one worth watching. He is the top steward on the cruise ship and he carries his authority carefully and ever so gently separate from himself, as you would a bowl of water. Casual efficiency is ingrained in his manner. He does not hurry but the ward is his domain and he notices everything in it.

He is busy. I have to be quick, seize the moment and step in. Tom’s stitches, I say to him, are they going to be done soon? When one of the nurses is ready, yes. No way to finesse this. He must know what she is like. Can I just ask that it is not Donna? He has grey eyes the colour of Herdwick wool and he turns them on me. Yes.

Charlie is as good as his word. The German nurse takes out the staples very deftly, starting from the bottom, one by one. The bloodied metal brackets clang on to her tray. They look like insects, stuck with matter and bits of hair. In Africa, army ants are sometimes used to do the job of sutures. Here they are simple metal staples. It is no trouble. We wait some more.

We have started to notice a pattern. There are spaces where we are delivered news. They tend to be spaces rather than actual places: generally improvised, porous, makeshift and vulnerable to intrusion. It seems that the delivering of news, however catastrophic, is not regarded as an endpoint in itself but has the status of a transaction done in the open like a piece of knowledge passed from hand to hand on the way to or from somewhere more pressing. Physical interventions – the removal of the staples – are given a site. Yet beyond a single fit, Tom has no symptoms by which we might know he is ill, so knowledge for us is everything. The disease is invisible, and talking about it is the way we feel its charge. Yet we are never presented with sites that might hold a theoretical explosion or contain its profound impact: the dissolution of the floor, folding in of doors and walls, sudden drops in pressure, the creation of a vacuum, the appearance of a void. So all our news, great and terrible, is imparted in liminal spaces. In between. I can name them: the telephone, a pale green transit room opening out on two sides on to adjoining clinics, a swing door, a tiny office crammed with chairs, computers, files and a shredder. This last had a door that could be shut, so it counts at least as a room.

After the removal of the staples and a further half hour waiting, this is where Tom and I; Mr K, the surgeon; and Charlie, the charge nurse meet so that Mr K can give us the biopsy results. The room is so small that once we are seated, in order for anyone to leave we all must rise again. The legs of the four swivel chairs are entangled. No one can exit independently, as the chair-mass blocks the door. The window cannot be opened. A large rubbish bin takes up priority space.

There is no preamble. The biopsy results are as bad as they can be. Grade 4 – glioblastoma multiforme. This is the new name we are given. I hear a short suite of words – aggressive – early – small – encapsulated. Even in the delivery of wholly violent news I notice Mr K’s voice is emollient and slightly hesitant as if to soften the blow, making me think the news might actually be worse in reality even than this. More words are said but the air in the room has fused with the air inside my body, making it difficult for breath to come or go.

This should not be Mr K’s job. All praise to the surgeon. He is the one with the good hand and as the bad messenger he is not in his element. His manner and words are functional and in no way sweet as the high art of his knife. We who are good at words would be better than him at this but in this foursome we are suddenly wrong-footed. Something new and strange has happened. We are the victims. I don’t know yet what this means but the ground we stand on has gone.

I have to get out in order to think. The news is the whole matter of the meeting so once it is delivered there is little else to say. We rise as a quartet and for a moment the four of us are locked together in an awkward folk dance of non-specific crossing and shaking of hands, symbolic bows of the head, murmurs of thanks and goodwill. What has just happened? We leave.

By heart I know that our route entails a series of right angles, starting with a turn left out of the little room. Thereafter we turn right, out of the ward, out of the hospital, out of the square, out. We walk side-by-side, mute and fused by heat and common danger. My eyes are filmed with fluid that doesn’t fall but hangs as a vertical screen. Through it I see the streets are very crowded but I don’t notice anything again until we get to the river.

1.10

9 October 2008

Dear Friends

The struggle continues. The biopsy showed that Tom’s tumour was malignant. The surgery went very well but he will need a course of radiotherapy, beginning quite soon, and going on for six weeks (that is, going into St Thomas’s each day, for a short blast, for five days each week). Tom is otherwise making a good recovery from the operation. He looks and feels well.

The next couple of months of treatment are going to be pretty difficult. So we say again, it’s important to us at this time that our friends stay in touch. Please do continue to write, phone, text, email, visit us, and so on.

With love

In September, though deaf to all but our own noise, I pick up the sound of the outside world collapsing. The value of money being wiped off the international markets makes no noise in itself. Loss has local impact. But to the accompaniment of smashing glass and metal, chairs hitting pavements from the fifteenth floor and the collective hum of all the air-cons in America, the big ones go down: Lehman Brothers, AIG, Merrill Lynch, Washington Mutual. Conversely the media goes up like a great big helium balloon. They are making up the deficit in talk. What could be more thrilling than the collapse of the financial systems of the West?

In Clapham after dropping Ev off with a friend I stand on the pavement and stare at a cash machine as if it is a threat. I am there so long someone asks me if I am planning to use it and if not, would I mind moving. My head feels fuzzy and ever so heavy. I would like to rest it on the pavement. I know that our problems are insoluble with money but I wonder if I should be clearing out my bank account.

I leave my pounds where they are. A dream like a brackish stream is going by. I had assumed, like many of my kind, that we would live happily forever. Our future was moored together. We weren’t going to divorce, that was clear, and we weren’t going to die until we did, in the far distance: old, not without pain but not until a time that made sense, discreetly one before the other or the other way round, leaving a gap, in which whosoever it was who was still living could wonder, drift, mourn, prepare and cease in their turn.

1.11

So what did you do when death came to your house?

We continued in the same way as before.

What is that, a failure of the imagination? Are you in denial?

This is not wholly true; we continue in the same way as before but in parenthesis. My thinking has switched its grammar. The present-continuous is its single operational tense. Uncertainty is our present and our future. Unlike an abstract or esoteric linguistic problem to be puzzled over, this has the force of a wholesale conversion experience. You are alive, this is your life becomes You are alive, this is your life. Once the nature of the threat is known the defences are brought out at high speed and within multiples of days they are fully rolled out. As well as the surgeon, Mr K, we are assigned an oncologist, Dr B. We are booked to see the neurologist, Dr H. We meet the chemo nurses and Tom is fitted for a radiotherapy mask. We wait for the regime to begin.

But the surface of us appears to be very much the same and this is an early stage intimation of a radical marvel – the flicker between the steadiness of the quotidian and the crash-consciousness of its ending. To call it even a flicker is an overstatement. The difference between the two states is imperceptible and total. One mindset cannot be attentive to both in the same moment, yet it must. We are in mortal danger and we fall about laughing at what Ev comes up with. We are forever dropping our guard and picking it up. Dropping and picking up are indivisible. They are the same act. The two states are so fused that the switch is not apparent.

Everything living bears the fact of its own dissolution. This is a given. But for us it has become tangible. The universe as experienced is not universal. The universe as experienced is personal. It turns its face towards the individual. It presents an individual form. This individual form is ours. All that adheres will be lost.

Yet there are social and domestic pleasures. And they continue. Decisions that needed to be made two months ago still need making. What shall we eat? Where shall we go this evening? I paint our bedroom, not a pressing decision, but what colour should it be? The job has a clear outline, a beginning and end. It is an act of defiance. I crouch on the floor to paint the skirting and hide my face in cornice and cupboard. Low at the carpet where no one will ever look is a long clean edge of white paint at the join of skirting and wall. The line does not waver. I cut corners but I am experienced and I have a good straight hand. The colour of the wall ends up green or perhaps blue, both shades notoriously difficult to assign but the one I choose is deep and saturated. It will soak up all the sunsets that reach us and retain them hard against the retina like a battery.

There was always so much to be done. And now there is so much more. As Ev gets older the generalia around him multiplies: baby stuff, friends, park, all kinds of play. Tom coming home from hospital brings oxygen back to the house and Ev is invigorated. We see a lot of friends. They all want to come round to verify his continuing existence. Salute the brain. They are reassured. He is the He of He. I welcome them but when they come it’s true I remain in tension until they go. I am without conversation and without insight. I have occasional flashes of wit but free-floating, not tied to anything and my words come out impetuous and sudden, like a small child’s vomit.

Tom is mending beautifully from the intrusion into his head and we have a string of gorgeous days. Then, one morning ten days in, he has a violent fit. Somehow, though it seems obvious in retrospect, we were not warned that this might happen. It is more disastrous for me than for him. I get to see it. Though it brings an immediate backwash of physical and mental exhaustion, he recovers himself. I do not. I learn something. Here, we commence. We stand at the beginning.