Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

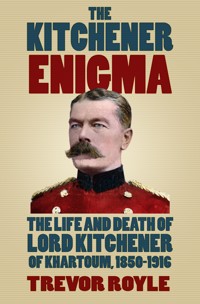

In this critically acclaimed biography, now fully updated, Royle revises Kitchener's latter-day image as a stern taskmaster, the ultimate war lord, to reveal a caring man capable of displaying great loyalty and love to those close to him. New light is thrown on his Irish childhood, his years in the Middle East as a biblical archaeologist, his attachment to the Arab cause and on the infamous struggle with Lord Curzon over control of the army in India. In particular, Royle reassesses Kitchener's role in the Great War, presenting his phenomenally successful recruitment campaign – 'Your Country Needs You' – as a major contribution to the Allied victory and rehabilitating him as a brilliant strategist who understood the importance of fighting the war on multiple fronts.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 751

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Preface and Acknowledgements

Prologue

1 An Irish Boyhood

2 A Sapper in the Levant

3 Egypt: Riding the Desert Sands

4 Sudan: Planning for Victory

5 Omdurman: The Making of the Legend

6 Symbol of Empire

7 The Great Boer War

8 India: Commander-in-Chief

9 Egypt Again: Proconsul

10 War Lord: Raising the New Armies

11 The Need for Shells

12 Strategy on Three Fronts

13 Erosion of Power

14 An Unpitied Sacrifice

15 The Kitchener Legacy

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is being republished in 2016 to commemorate the centenary of the death of Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum. It was first published in 1985 under the title The Kitchener Enigma and I have used the opportunity to make corrections, where necessary, to the original text. I have also reduced the length of the book and, more importantly, have recast the chapters dealing with Kitchener’s role in the First World War to take advantage of the advances in scholarship that have taken place over the last thirty years. In this respect I am particularly grateful to have had sight of recent work undertaken by George H. Cassar, David French, Keith Neilson and Peter Simkins, whose Kitchener’s Army: The Raising of the New Armies 1914–1916 must be the definitive account of the formation of the largest British Army in history.

The suggestion to republish my book came from Michael Leventhal and I am grateful to him and the staff at The History Press for all their help and encouragement during the editing and recasting process.

Debts remain from the first edition and my first is to the members of the Kitchener family who provided me with access to previously unpublished letters and papers relating to Kitchener’s private life. Mrs Anne Edgerly, Kitchener’s great-niece, allowed me to borrow her collection of private letters written by Kitchener to his sister Millie between 1870 and 1899. The late Earl Kitchener lent me Sir George Arthur’s notebooks and a selection of miscellaneous papers relating to his great-uncle. My thanks to him and to his sister, Lady Kenya Tatton-Brown, for their support and generous hospitality.

For help in researching Kitchener’s childhood in Ireland, I must thank, first and foremost, my good friend the late Colonel Eoghan O Neill, to whom the original biography was dedicated. Through him I was introduced to three historians who gave freely of their time and experience to help me uncover some of the facts about the Kitchener family’s residence in Ireland. They all have my thanks: Dáithi Ó hÓgáin, University College Dublin; Donall Ó Launaigh, National Library of Ireland; and Padraig Ó Snodaigh, National Museum of Ireland. Father J. Anthony Gaughan allowed me to use material from his extensive research into the local histories of Limerick and Kerry; Bryan MacMahon of Listowel and John Savage of Tralee helped in similar fashion, as did Seamus McConville, editor of The Kerryman. Dr K.P. Ferguson of the Military History Society of Ireland, and Irish labour historian Sean Hutton provided me with many useful leads in understanding Kitchener’s attitudes to recruiting in Ireland during the First World War, and at a crucial stage in my examination of the Redmond Papers I was helped greatly by the insights provided by my good friend Owen Dudley Edwards, erstwhile Reader in Commonwealth and American History at the University of Edinburgh.

The late Sir Philip Magnus-Allcroft, a distinguished earlier biographer of Kitchener, commented on some of my findings and offered kindly encouragement, for which I am most grateful.

For their insights into the sinking of HMS Hampshire I owe thanks to John R. Breckenridge, who organised the underwater surveys of the wreck in 1977 and 1983, and to his associate Dr Larry McElroy, who gave me sight of his written research findings. Ex-Stoker F.L. Sims, the last living survivor of the Hampshire’s crew, allowed me to interview him: many of his comments on the disaster are contained in Chapter 14. He has my thanks.

Others who discussed with me aspects of Kitchener’s life or who helped in other ways and to whom I owe thanks are: Derek Bowman, Dr Paul Dukes, Chris Graham, Callum Macdonald, Neil Mackay, Sorley MacLean, John Montgomery, Hayden Murphy, Walter Perrie, Lindsay Phillips, Dr Jill Stevenson and Francis Stuart. With the passing of the years some are no longer with us but their help and encouragement remain strong in the memory.

Libraries and their staffs must come high in the regard of any self-respecting author, and here I was not lacking support and helpful suggestions. Alan Taylor, formerly of the City of Edinburgh’s library service and now a distinguished author, was always sympathetic and painstaking with my many requests for books and papers, and as ever the staff of the National Library of Scotland provided me with books and manuscripts in their customary professional way. I was equally well provided for at the Public Record Office, Kew (now the National Archives), which holds the principal Kitchener manuscript collection, as well as the Admiralty and War Office papers and other private collections quoted in the text. I should also like to thank the staffs of the libraries at the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum, the National Maritime Museum and Kirkwall Public Library, whose librarian, the late John L. Broom, provided me with useful newspaper cuttings relating to the loss of HMS Hampshire.

The author and publisher would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce their photographs in this volume: National Army Museum (pictures 1, 12, 13, 20, 23, 26 and 28), Illustrated London News Picture Library (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 14, 15, 16, 21, 25, 30, 32, 33, 34, 36, 45, 46, 47 and 48), Mansell Collection (4, 7, 9, 22, 24, 29, 35 and 44), Imperial War Museum (10, 37, 38, 39, 40 and 41), BBC Hulton Picture Library (11, 19, 31, 42 and 43), Punch (17, 18, 27 and 49).

PROLOGUE

To most people, those who knew him by virtue of their service with him, or those who recognised him only by his beckoning finger and imperious wartime command to serve their country, Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl of Khartoum and of Broome, was an enigma.

Given to being both anti-social and a stern taskmaster, he found it difficult to express his innermost feelings and frequently retreated behind a public persona consisting of cold unblinking eyes, a luxuriant moustache and a taciturnity that defied encroachment. Yet Brigadier-General Frank Maxwell, VC, whom Kitchener called ‘The Brat’ and who was his ADC and confidant from 1900 to 1906, was moved to write to his father that ‘He [Kitchener] really feels nice things, but to put tongue to them, except in very intimate society, he would rather die.’1

Kitchener discouraged close acquaintance, even with those who served on his staff, yet he was given to sentimental gestures to those whom he admired or to those who had given him their loyalty. In August 1915, at a time when the nation was beginning to accustom itself to the big losses of the First World War following the Battles of Neuve Chapelle and Festubert, Kitchener lapsed into tearful silence on hearing the news of the death of Julian Grenfell, the much admired poet son of his friend Lord Desborough.

Kitchener was also a man who believed that he was defrauding the Almighty if he were not doing his full duty, but that belief in hard work also carried with it the fear of failure. ‘I wish you could tell me more what I’m doing wrong,’ he asked Lord Derby, his Director-General of Recruiting in 1915. ‘I feel there is something more I ought to do for the country. I am doing all that I can and yet I feel that I am still leaving much undone.’2

His ambition, which his detractors thought undisguised and vainglorious, took him to become Sirdar, or Commander-in-Chief, of the Egyptian Army; Governor-General of the Sudan; Commander of the British forces during the Boer War; Commander-in-Chief of the army in India; and British Agent and virtual ruler of Egypt. In turn he became one of the best-known symbols of Empire yet, when he was invited in August 1914, it took all the persuasion of his Prime Minister to make him Secretary of State for War.

In his private life he enjoyed collecting porcelain and antique furniture, practised flower-arranging, enjoyed inspecting a well-set dinner table, and amongst connoisseurs was considered an expert in chinoiserie and medieval armour. He turned his home at Broome Park in Kent into a personal monument to his many successes; nevertheless he shunned publicity and kept his personal life so private that only his sister Millie and a few chosen friends were privy to his innermost thoughts. Even his death was shrouded in mystery and rumour.

Given so many contradictions it is perhaps in the nature of this paradoxical man that it should have been someone who generally disliked him, David Lloyd George, who came closest to making the most pertinent remark about Kitchener when he compared him to ‘one of those revolving lighthouses which radiate momentary gleams of revealing light far out into the surrounding gloom, and then relapse into complete darkness’.3

Even though Kitchener lacked the common touch of Field Marshal Lord Roberts, who was known by the homely soubriquet of ‘Bobs’, the British public worshipped him: yet all the hero-worship of earlier years was to pale into insignificance with the appearance of his famous recruiting poster during the early months of the First World War. Drawn by Alfred Leete, a self-taught artist from the West Country who had left school at the age of fifteen to pursue his chosen career, the design first appeared on the front cover of the magazine London Opinion on 15 September 1914.

It was a brilliant concept, and one of the simplest and most effective designs created by any artist of the war. It was quickly taken up by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, an all-party group headed by the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, Andrew Bonar Law, the Leader of the Opposition, and Arthur Henderson, the leader of the Labour Party. The committee first met on 31 August 1914 and was responsible for producing a series of recruiting posters designed to pull at the heartstrings of Britain’s manhood. Other powerful posters with emotional slogans were ‘Take up the Sword of Justice’ depicting the loss of the Lusitania, and ‘Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?’ with its uneasy mix of domesticity and belligerence; but none had the simple directness or brought home the propaganda message more clearly than the creation of Kitchener as a messianic recruiting sergeant.

Later in 1914 the poster appeared in a number of guises but the centrepiece was always Leete’s original interpretation, the pointing finger and behind it the bushy moustache. Their owner was not averse to being depicted in that way if it served the army’s purpose, although he insisted on the addition of ‘God save the King’. Since 1913 the War Office had employed the Caxton Advertising Agency to brighten up its recruiting campaigns and on the outbreak of war Sir Hedley Le Bas, Caxton’s owner, was quick to recognise the value of Kitchener to the cause:

I knew the solid advantages of that wonderful name and personality, with the power to move people and inspire them to patriotic effort. The right to use the name made the enormous task of finding a new army all the easier. We who managed details of the publicity campaign had a name to conjure with – a good will already created. So in all the appeals put out Lord Kitchener’s name was our great asset and was never absent from them.4

And that good will counted for much. With the exception of Winston Churchill in 1940 no other British war leader has excited so much public enthusiasm for the country’s call and in the early part of the First World War Kitchener was looked upon as the personification of the nation’s will to win. Later the Prime Minister’s wife, Margot Asquith, who had once lionised Kitchener, remarked unkindly that he might not be a great man but at least he was a great poster.5 Her throwaway remark was repeated gleefully by Kitchener’s enemies and after his death in 1916 his recruiting poster seemed to mock its original intentions. When it was revived in the 1960s it was little more than a crude advertising symbol, also the motif of Carnaby Street and ‘Swinging London’. With the cheapening of the poster Kitchener’s star had also fallen and by the time his features were appearing on coffee mugs and badges, on T-shirts and posters, the famous moustache had become a joke, a relic of Britain’s long lost past.6

Yet Leete’s poster is also full of contradictions. The face is clearly Kitchener’s, but Kitchener’s crudely depicted as a younger man – in 1914 he was sixty-four, greying and heavy featured. Even the eyes are wrong, beetling and too closely set together, although Leete was careful to give them a cold arresting quality to increase the poster’s impact. Only the moustache is Kitchener’s, the instantly recognisable and bristling hallmark of the stern warrior. Any evaluation of the poster is bound to be unrewarding when it is compared to the photographs of the man himself. As a young man Kitchener was more than a little vain of his appearance and his photographs from that period show him to be handsome, if somewhat reserved. His eyes, piercingly blue and set far apart in a large face, were especially noticed. ‘His head was finely shaped, and the eyes, blue as ice, were in early life of singular beauty,’ wrote his colleague Lord Esher. ‘Sandstorms and the Eastern sun ruined them in later years.’7 Standing 2in over 6ft, Kitchener used his height to advantage to stare haughtily over the heads of those who stood before him. His large square frame, angular build and commanding presence set him apart from an early age and in later life his face was made distinctive by its high colour, the ‘sunburnt and almost purple cheeks and jowl’ making a ‘vivid manifestation upon the senses’ of the young Winston Churchill at the end of the campaign in the Sudan.8

None of us can escape the legacy of our appearance. From his youngest years Kitchener’s looks attracted much comment: he was considered by many to have been almost too handsome for his own good in his youth, yet he allowed himself in later life to become a prisoner to his moustache. In the manner of the times Kitchener was invariably photographed looking fixed ahead, seeing only what he wanted to see, oblivious to all distractions. But there is a curious indecision and gentleness in the eyes. It is the face of a man who did not want to be forgotten.

Notes

1 Maxwell, Frank Maxwell VC, 89

2 Grew, Kitchener and Empire, I, 13

3 Lloyd George, War Memoirs, II, 751

4 Sir Hedley Le Bas, ‘Advertising for an Army’, Lord Kitchener Memorial Book

5 The claim was made by Philip Magnus in Kitchener, 289, but in her autobiography More Memories (1933) Margot Asquith insisted that the comment was made by her daughter, Princess Elizabeth Bibesco

6 The phenomenon is discussed in James Taylor, Your Country Needs You, Glasgow, 2013 and is dismissed as ‘an urban myth’

7 Esher, Tragedy of Lord Kitchener, xvi

8 Churchill, My Early Life, 176

1

AN IRISH BOYHOOD

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born on 24 June 1850 at Gunsborough Villa, an unpretentious shooting lodge standing some 3 miles from Listowel in County Kerry in south-west Ireland. Later in life he was noticeably reticent about some of his family background, but whenever it was hinted that he came from Irish stock Kitchener would demur and repeat the Duke of Wellington’s disclaimer of his own birth in Ireland that ‘A man can be born in a stable and not be a horse’.

Like many other English families who settled in Ireland, the Kitcheners were always anxious to emphasise the purity of their English origins. These can be traced back to the reign of King William III when they were churchwardens of the Church of Holy Cross in the parish of Binsted on the Hampshire downs. In 1666 a Thomas Kitchener left Binsted to become an agent to Sir Nicholas Stuart of Hartley Maudit, whose estate was at Lakenheath in Suffolk. His grandson, also called Thomas, had three sons, the eldest of whom, William, became a successful tea merchant in London: this was a period when London was emerging as one of the world’s great commercial centres and the city’s merchants prospered accordingly. William also extended the family’s fortunes by rising in society. He became a member of an ancient guild, the Clothmakers’ Company, and his sister Elizabeth married a brother of the foreign editor of The Times, Henry Crabb Robinson, whose diary and correspondence threw much interesting light on the lives of his friends and fellow writers Wordsworth, Coleridge, Lamb and Hazlitt.

William Kitchener married twice, for the second time in 1797 to Emma Cripps, by whom he had three sons, the youngest being Henry Horatio Kitchener, the father of the future field marshal. He was born on 19 October 1805 at the family home at 8 Bunhill Row in Moorgate and he was named for Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, whose death at the battle of Trafalgar took place two days later. The young Henry Horatio Kitchener was also to follow the profession of arms but he foreswore the navy for the army, being commissioned in 1830 into the 13th Light Dragoons. In 1845, as a captain, he married Frances Ann, the daughter of the Reverend John Chevallier of Aspall Hall in Suffolk.

If the Kitchener family was solidly and unprepossessingly English, by comparison the Chevalliers were glamorous and romantic. Of Huguenot stock, they had owned the handsomely proportioned Aspall Hall, near Stockmarket, since 1702 and down the years they also owned the living of Aspall, a benefice that allowed the eldest sons of the family to continue living in landed ease. Frances’s grandfather, Temple Chevallier, was a scholar of Magdalene College, Cambridge; her uncle, Temple Fiske Chevallier, was a noted astronomer and a pioneer of science in education; and her own father, John, was a qualified physician who interested himself in agrarian improvement and the care of the mentally ill as part of his duties as the rector of Aspall. He married three times, his third wife, Elizabeth Cole of Bury (Lancashire), presenting him with five children, of whom Frances Ann, or Fanny, was the youngest. In their turn, five children were born to Henry Horatio and Fanny: Henry Elliott Chevallier (1846), Frances Emily (Millie) Jane (1848), Arthur (1852), Frederick Walter (1858). Horatio Herbert, being born in 1850, was therefore the third child and second son: from his father he borrowed Nelson’s Christian name but throughout his life the family knew him as Herbert. In his adult years Kitchener was to be much taken with his Chevallier connection and the family followed his career closely. Whenever he could, he visited Aspall while on leave and when he came to be raised to the peerage in 1898 he took as part of his title the name of his mother’s childhood home.

Shortly after their marriage Fanny accompanied her husband to India, where he reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel. However, shortly after the birth of Chevallier, their first child, her health wilted and Colonel Kitchener decided to bring his family back to Britain where he transferred on half-pay to the 9th Regiment of Foot (later The Norfolk Regiment). Being put on half-pay was not an unusual experience for the Victorian army officer but it was a setback as it did not count towards an officer’s career; also, if he remained on the half-pay list for more than two years compulsory retirement followed. After chasing appointments in Whitehall during the course of 1848, Colonel Kitchener finally decided to leave the army. He sold his commission early in the following year and determined to seek a more modest living elsewhere, in Ireland.

At the time, in 1849, Ireland was just coming to the end of the Great Famine, a disastrous four-year period that saw the failure of the potato crop, the staple foodstuff, bring huge distress to the rural population. To combat the effects of the subsequent evacuation of the rural areas and to infuse new capital into Ireland the government passed the Encumbered Estates Act of 1849 by which bankrupt estates could be sold to land speculators. On completion of a sale through the Encumbered Estates Court in Dublin the purchase money would be distributed amongst various claimants and the residue paid to the seller. Of the 7,200 petitions heard by the Encumbered Estates Court that year some 300 came from Britain: one of those successful was Colonel Kitchener.

Early in 1850 Colonel Kitchener bought the estate of Ballygoghlan, on the Kerry-Limerick border between Moyvane and Tarbert at the mouth of the River Shannon. The once thriving estate had been ruined by the famine, its village of the same name was deserted and the house itself was in such a condition of disrepair that the family could not immediately move in. While Colonel Kitchener busied himself with supervising the necessary alterations his wife stayed with a family friend at Gunsborough Villa, near Lisselton on the road from Listowel to Ballybunion, and it was while she was there that her third child, Horatio Herbert, was born during the early part of the summer of 1850. Three months later, on 22 September, he was baptised at the Protestant church of Aghavallen at Ballylongford. His godmother, Miss Mary Elliott, was the daughter of another English landowner at Tanavalla near Listowel. By the year’s end the Kitcheners had moved into their new home and appointed a nurse for the children, Mrs Sharpe. Her memories paint a vivid picture of family life at Ballygoghlan.1

As was the case with the majority of the British speculators who bought land under the terms of the Encumbered Estates Act, Colonel Kitchener’s presence caused a good deal of local resentment. Many bankrupt estates had been sold at the insistence of creditors and the new landlords were often only intent on getting a quick return on their capital outlay. They might have improved their properties and introduced new methods of agriculture but they were not always respecters of tenants’ rights. As there was no law to protect the Irish peasant from rack-renting and eviction, the landlords used that freedom to coerce tenants into becoming little more than poorly-paid labourers and considered themselves free to evict those who failed to keep up with the increased rents.

It was not long before Colonel Kitchener exercised his rights in an attempt to make his estate quickly profitable. When one of his tenants who could not meet the new rents was evicted from his property the colonel ordered his bailiffs to set their dogs on any who disobeyed his orders. According to local tradition the tenant’s family was also horse-whipped before the roof was burned off their cottage, thus making it no longer fit for human habitation. The incident may have been typical of many others perpetrated during those years but it created a good deal of outrage in the vicinity. Colonel Kitchener, like most of his class, underestimated the determination of the Irish peasants not to abandon land they took to be theirs by right of inheritance and his actions made him a hated figure.

Not long after that incident Colonel Kitchener evicted one Sean MacEniry, an articulate farmer who gained some measure of revenge by composing folk verses that lampooned his landlord.2 The main thrust of his insults was MacEniry’s claim that Colonel Kitchener suffered from bromhidrosis, an unfortunate malady characterised by a fetid stench from the body’s sweat. Known in Irish as boladh an tsionnaigh (stench of the fox) or as boladh an diabhail (stench of the devil), the complaint is considered in the local folk traditions of Kerry and Limerick to be ‘the mark of utter depravity’.3 Yet in carrying out evictions from his property and by behaving harshly towards his tenants, Colonel Kitchener was merely behaving like many other English landlords of the time. In their eyes, peasant-Ireland, tied to superstition and the Catholic Church, Gaelic-speaking and largely hostile to its landlords, represented a people who had to be brought within the ‘civilising’ influences of Victorian expansion and profit-making. Recent outbreaks of terrorism by various nationalist groups had only confirmed British distrust of the Irish and it was hard for the parliamentarians in London to grasp that the situation could only be retrieved by putting right fundamental grievances, especially those concerned with land tenure. The gulf between tenant and landlord was wide and Colonel Kitchener never made any attempt to bridge it: his children were brought up to look upon themselves as belonging to a superior race and from an early age his sons, noticeably Herbert, behaved in an imperious and arrogant way towards the Irish.4

However, Colonel Kitchener was determined to make his estate prosper and by 1857 he felt confident enough to extend his holdings by taking on Crotta House in Kerry, a seventeenth-century pile with an imposing front porch near Kilflynn, halfway between Listowel and Tralee. It had belonged to the Ponsonby family, which was part of the great house of Bessborough, and its acquisition was an outward sign of the colonel’s continuing success. As a result, Herbert’s childhood days were divided between the two houses but, although Crotta was the grander of the two with its large garden and views of the Slieve Mish mountains to the south-west, it was always regarded by the children as less homely than Ballygoghlan.

Family life was run on military lines and Mrs Sharpe, the governess, recounts how breakfast was served punctually each morning at eight o’clock and that even the maid serving breakfast to Mrs Kitchener in her bedroom had to wait outside the door until the clock in the hall struck the hour.5 Punishment, too, was meted out on martial lines and the boys were encouraged to develop a sense of discipline based on a code of mutual honour. Tale-telling was frowned upon and stoicism of body and mind encouraged: when, for instance, at the age of ten Herbert damaged his hand with a large stone he retired to his bedroom and would not allow his mother to be told of the injury. Before saying goodnight to her he hid his hand in his jacket sleeve behind his back so that she would not be alarmed. On another occasion he suffered without complaint the punishment of being pegged out for a minor offence – this involved him being spread-eagled beneath the summer sun on the front lawn with his hands and feet tied to croquet hoops.6 And when he fell from his horse and injured his arm while hunting, his father ordered him to remount and continue the chase. This, too, he suffered without complaint.

Colonel Kitchener also employed his boys as additional hands to help in the improvement of his estates. According to Stephens, the colonel’s steward, young Herbert was the equal of any man on the estate when it came to the cutting of turf and his father trusted him with the herding of cattle to market in Listowel although, in strict accordance with his instructions, the manager of the Listowel Arms Hotel was forbidden to serve the boy with breakfast until all the cattle had been sold.7 As their father had a dislike of formal schooling, the boys’ education did not pass beyond elementary instruction at the village school in Ballylongford: yet, on receiving a teacher’s report that Herbert was a dullard the colonel flew into a rage and threatened to apprentice his son to a hatmaker. Consequently, private tutors were employed but this proved an unsatisfactory solution. Some years later, in 1867, when Herbert’s learning was tested by his cousin Francis Elliot Kitchener, then a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, he was found to have only a rudimentary grasp of English and arithmetic and an almost complete absence of general knowledge.

Nevertheless, in his father’s eyes, those drawbacks were not of any immediate concern as he believed that his boys should be practical first and academic second. So it was against a background of hard physical work and equally strict discipline that Herbert’s childhood was spent. As a small boy he was pretty, fair and curly-haired, noticeable for his winning smile and arresting, sky-blue eyes.8 Later, his hair turned dark and he quickly outgrew his brothers, to become a handsome, lanky boy who seemed in his teenage years to be too tall for his strength. Nonetheless, he sat a horse well, and local tradition has it that, whenever he took cattle to market, he would delight in trying to chivvy them into a semblance of order. Certainly his erect military bearing was long remembered in the district.

Two anecdotes from his boyhood give a clue to the future man. One day his mother found him weeping inconsolably after coming across four dead fledglings in a felled tree: each bird had to be buried with great solemnity before he regained his composure. His mother worried about that side of his nature, fearing that he might repress his emotional instincts and so damage himself by his own self-discipline. Indeed, as he matured, Herbert tended to hide his sensitive side and adopt instead many of his father’s mannerisms. Once, while watching estate workers felling trees, he struck a boy called Jamesy Sullivan across the knuckles with his riding crop. Stung by the assault, Sullivan turned on Kitchener and struck him from his horse, knocking him unconscious. Such an attack would have spelled immediate dismissal and ruin for the workers but, on coming round, Herbert refused to tell his father or to have the men punished. That degree of sensitivity, aggression and aloofness, when mixed with a sense of high moral purpose, was a powerful combination, and it turned Kitchener into a reserved and complicated young man. He preferred keeping himself to himself, and his family and friends noticed that, apart from the love he lavished on his frail, pretty mother, he disliked baring even the slightest emotion in public.

Although Colonel Kitchener was a stern father with an unpredictable temper, he lavished much care and attention on his wife and encouraged his children to adore her, too. The poor health that had attended her in India had followed her to Ireland and she became a prisoner to incipient tuberculosis. The south-west of their adopted country, with its temperate but damp climate, was not an ideal one for her condition, nor was it helped by the eccentricities of her husband’s domestic arrangements. He hated to sleep beneath blankets, believing them to be unhygienic: instead, he preferred to cover their double bed with sheets of newspaper, specially sewn together, which could be varied in quantity according to the season of the year.9 In that way, he argued, cleanliness could be allied to economy. While such a bizarre regime may have been suitable for a robust man such as the colonel, it was bound to have a deleterious effect on his wife.

On the whole, their time in Ireland had been unhappy for Fanny Kitchener. Her childhood and early years had been spent in comfort and ease at Aspall and she was used to a close and tightly-knit society that revolved around visits, musical evenings and gossip. Ballygoghlan was a gaunt and uncomfortable house, difficult to heat, and the winter evenings were long and cold. The houses of the surrounding English families lay far apart and it often took a whole day to make a visit. If she wanted to go further afield, it meant writing letters and staying the night. It was no place for a woman unless she shared with her husband the pleasures of the field, but Fanny had never been the outdoor type and gradually the circle of her existence narrowed to the two houses, her husband and the well-being of her children. As the years progressed she became increasingly unwell, and by 1863 she was virtually confined to her room.

The only remedy for tuberculosis known to the Victorians was treatment in the mountain air of Swiss health resorts. To have stayed on in Ireland would have spelled Fanny Kitchener’s doom and so during the course of that winter of 1863 her husband put in hand the sale of his Irish estates. It was a good time to put them on the market. The population decline and the increase in the size and prosperity of agricultural holdings, together with his own improvement of his estates, made Ballygoghlan and Crotta attractive propositions that brought Colonel Kitchener a ‘decent’ return on his original investment of £3,000 when he came to sell them in the early part of 1864 (roughly £256,000 today). The family moved to Switzerland, first to Bex, then to Montreux.

Little now remains to remind the visitor of the Kitcheners’ stay in the district. Ballygoghlan has long since disappeared but part of Crotta and Herbert’s birthplace at Gunsborough still stand, the latter for many years in the possession of the O’Dowd family. In the tiny Church of Ireland chapel at Kilflynn, where the Kitcheners used to worship, a commemorative tablet was erected after the field marshal’s death by a Mrs Tugham Hanbury, the wife of a naval surgeon. It gives his date of birth, wrongly, as 15 June 1850. Only once did Kitchener return to the south-west of Ireland, in the summer of 1910, when he made a motoring tour of Cork, Kerry and Limerick at the invitation of the Marquess of Lansdowne. He revisited some of the scenes of his childhood and, while in Tralee, was taken in a jaunting car to Crotta by the Savages, the family who had bought the estate and who continued to manage it. He astonished his hosts by remembering every field on the estate by its Irish name and he appeared to take great pleasure in walking through the house and its gardens recalling animatedly his boyhood days.10

After Ireland, Switzerland came as a rude shock. The town of Bex in the Canton Vaud was considered to be one of the best Swiss spas of the period. Its sulphur and brine baths were reputed to have qualities to dispel rheumatism and cure circulatory diseases, while the pure air of the mountains was supposed to work wonders for chest complaints. However, Fanny Kitchener’s condition did not improve and during the summer of 1864 the family moved again, to Montreux on Lake Geneva. It was to no avail and by the end of the year Frances Kitchener was dead. Unable to find his bearings Colonel Kitchener decided to remain in Montreux and to bring up his children in Switzerland where his expenses would be much lower than they would have been had he followed his inclination to return to England. At the year’s end, Herbert, Walter and Arthur were sent to school in Geneva before going on to boarding school at the gaunt Château du Grand Clos, at Rennaz near Villeneuve at the eastern end of Lake Geneva. By that stage Colonel Kitchener hoped that all his sons would pursue careers in the army.

Run by the chaplain to the English congregation in Montreux, Reverend Bennett, the school prided itself on its strict discipline and its ability to produce educated young gentlemen for the armed forces – those hoping to go to university were encouraged to return to England to be crammed by private tutors. The education at the Château du Grand Clos was well grounded, but elementary. Even so, Herbert found it a trial and as a result he worked hard to grasp the elements of grammar, science, mathematics and languages required to pass his entrance examination to Woolwich, the military academy at which cadets were trained for service in the Royal Engineers and Royal Artillery – against his father’s wishes he had decided not to try for the cavalry and opted instead for the Engineers. At this time he also became a proficient linguist, learning to speak German and French fluently: France in particular, the French people and all things French, were to be a lifetime’s source of delight.

In 1866 there was further change when his father remarried, his second wife being his daughter’s music mistress, Emma Green. The new domestic arrangements effectively broke up the family. The oldest brother, Chevallier, joined the army and married in 1877. Walter, too, became an army officer, being knighted and appointed a major-general before his death in 1912. Arthur became a scientist; but it was Frances Emily – ‘Millie’ to her brothers – who was Herbert’s favourite, and he was godfather to her second child. From his time in Switzerland until his appointment as Sirdar of the Egyptian Army in 1892 he kept up an intimate correspondence with her from which a picture emerges of Kitchener that is very different from the stern taskmaster of later years. Millie, who married Harry Parker of Rothley Temple in Leicestershire in 1869, remained a constant source of encouragement to her brother and a confidante of many of his most private thoughts and innermost emotions.

In order to consolidate his financial affairs Colonel Kitchener now bought land in New Zealand, then in the final stages of the land rush and development of the South Island, and later in 1866 he visited his estate near Dunedin where his youngest daughter, Kawara, was born in 1867. On their return the Kitcheners settled in Brittany, at Dinan, while the boys continued at school in Switzerland.

Kitchener’s strict diet of study and self-discipline at the Château du Grand Clos cured the academic inadequacies discovered earlier but they took their toll on his well-being. The cold and damp of the gloomy château did not help matters and it seems that the stress of working hard under those conditions helped to bring on a minor breakdown in the early spring of 1867. Alarmed, Colonel Kitchener ordered his son back to England to stay with his cousin, Francis Kitchener, in Cambridge. There he recovered his health and began a process of intense tuition for his entrance examination to Woolwich: for the final polish he went to London to study under a well-known army crammer, Reverend George Frost, whose home and study-centre was at 28 Kensington Court.

It was a fairly normal process for potential cadets to be given an extra course of study before the examination that would determine their futures, and Reverend Frost had an excellent reputation for ‘cramming’ his students for Woolwich – a glance at the results of the successful candidates confirms his status as London’s most successful tutor.11 Most of the boys in Herbert’s group had been to English public schools and as a species they were quite alien to him; so much so that his time in Kensington would have been quite barren had it not been for the company of a fellow student, Claude Reignier Conder, who became his first close friend.

Two years older than Kitchener, Conder was the son of a civil engineer who also contributed essays to the Edinburgh Review and most of his childhood had been spent in Italy, where his education had been completed and refined by a series of tutors. Before going to Reverend Frost’s he had spent some time at University College, London, where he laid the foundations of his later career as an archaeologist. Reserved and modest as a young man, Conder was a brilliant student who seemed to sail through the cramming course and when he first met him Kitchener stood in awe of his fluency and his urbane learning. In the examinations for Woolwich Conder gained a creditable ninth place in the entrance lists.

The Royal Military Academy at Woolwich had been founded by Royal Warrant on 30 April 1774 and for 200 years it was the cadet training establishment for most officers commissioned into the Artillery, the Engineers and, later, the Signals. Known as ‘The Shop’ – because its original home was in a workshop at the Royal Arsenal – during the 1860s it had been undergoing a process of rapid reform. Entrance examinations had been introduced, the harsher methods of discipline were being abolished and the buildings and barracks improved. By slow degrees the battle for professionalism in the army was being won and, although there had been cadet mutinies against conditions in 1861 and 1864, by 1868, the year of Kitchener’s entry, Woolwich was a tough, down-to-earth institution whose lieutenant-governor (commandant), Major-General Sir Lintorn Simmons, an engineer, insisted on high standards of learning and discipline.

To get into the academy the successful cadet had to sit an entrance examination of no little complexity. Twelve subjects were on offer – mathematics, classics, English language and composition, English history, geography, French, German, geometrical drawing, freehand drawing, experimental sciences, natural sciences and Hindustani – and each candidate had to be examined in five, one of which, mathematics, was compulsory. A total of 2,500 marks was the minimum successful total, of which 700 had to be gained in mathematics. When Kitchener’s time came – he was examined at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea between 2 and 11 January 1868 – he chose to be examined in mathematics, French, German, natural sciences and English history (he had already qualified in geometrical drawing) and from these he gained 3,753 marks, passing twenty-eighth in the list of fifty-six successful candidates. The highest mark of 6,452 was gained by an old Etonian, H.C. Chermside but, to put Kitchener’s placing and marks into perspective, of the 116 original candidates sixty had failed to obtain the minimum marks and so failed the examination.

Fortunately for Kitchener, Conder was still at Woolwich and the friendship between the two young men deepened. At that time Conder was perfecting his knowledge of Hebrew and he introduced the language to his friend, thus implanting in Kitchener his first interest in the culture of the Levant, the area of the eastern Mediterranean now covered by Lebanon, Syria and Israel. That study led them back to the Bible and the two men became interested in Anglo-Catholicism, the High Church element in the Anglican Church that had been associated earlier in the century with the Oxford, or Tractarian Movement. Its adherents emphasised the Catholic, as distinct from the Protestant, character of the Church and paid strict attention to the rituals of the Christian calendar, commemorating feast days and observing fasts such as Lent.

However, for the young Kitchener at Woolwich, it was not all hard work and religious enthusiasm. To his sister Millie he reported during his first term in the spring of 1868 on the successful outcome of a sports day with flat races and steeplechases after a sumptuous luncheon in the gymnasium attended by the Prince of Wales and Prince Arthur of Connaught. Kitchener entered his horse in three races but did not win anything, partly because he fell at the water jump, a monstrous affair ‘about 20 feet square and five feet deep filled with water. Nobody being able to jump it every body went in. Some dived in and swam across. Others stumbled through it. In fact it was a most amusing sight for all except those that were in the water like me.’ Not without a little pride though, he confided that she would be struck with awe by his ‘military swagger’ and by his ‘giving the orders in a very imposing voice’.

In the summer of 1868, for his first break from Woolwich, he holidayed alone in the West Country, but instead of touring, as he had originally intended, he stayed for a few pleasurable weeks in Truro. Apart from walking with friends to The Lizard and to Land’s End and delighting in the wild beauty of the Cornish coastline he had other more pressing reasons for enjoying his first real holiday. His vanity, he wrote again to Millie, had been greatly indulged as ‘the few young ladies that Truro boasts of … see so very few young gentlemen that they are very different to les filles de Londres’. Four very pretty girls from the Chilcot family took his eye and with them there were picnics, expeditions, boating trips and croquet on the lawn. It was all very agreeable and on one never-to-be-forgotten evening there was dancing in their house by candlelight when he was the sole object of their attentions. As he wrote to Millie:

Think of me with four young ladies, each longing for her swain. I really thought I should break a blood vessel or do something dangerous as they each caused great strain upon my legs. However I got over it and enjoyed it very much as the candle which lighted us was put out quite by accident and we got on very well without it.

He was eighteen, it was high summer and he had four pretty girls vying for his attention, the dream of any red-blooded young man. The next day he woke to ashes as the Chilcots ended their holiday and their dancing daughters passed out of his life.

There were other flirtations, too, while he was a cadet; one girl in particular, Eleanor Campbell of Thurmaston Hall in Leicestershire, took his fancy, but ‘Nellie’ was destined to marry in 1887 his future colleague in Egypt, Leslie Rundle. In his adult years, Kitchener kept a firmer check on his emotions but never again was he to feel quite as comfortable in female company. Even so, a sense of gallantry never deserted him and as a young man there is little doubt that he was well aware of and responsive to the attractions of girls.

Kitchener spent two years at Woolwich and passed out in December 1870, having missed one term in his second year due to illness and the stress of having to keep up with his colleagues. In spite of his hard work, his cadetship had been undistinguished: like many another man who achieved greatness in later life, Kitchener’s early development was slow.

Notes

1 NA PRO 30/57/93, Kitchener Papers. Mrs Sharp to Sir George Arthur in response to requests for biographical material

2 J. Anthony Gaughan, Listowel and its Vicinity, Cork, 1973, 216

3 Ibid, 316

4 Magnus, Kitchener, 4

5 NA PRO 30/57/93, Kitchener Papers, Mrs Sharpe to Sir George Arthur

6 Magnus, Kitchener, 6

7 B. Beatty, Kerry Memories, Camborne, 1939, 26

8 NA PRO 30/57/93, Kitchener Papers, Mrs Sharpe to Sir George Arthur

9 Magnus, Kitchener, 6. This claim was disputed by the Kitchener family

10 Information from Mr John Savage, Tralee

11 Report on the Examination for Admission to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, held at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea on 3 January 1868, and following days, London 1868

2

A SAPPER IN THE LEVANT

Kitchener’s report on leaving Woolwich was not encouraging. Although his qualities as a linguist were noted and he was known to be a fine horseman, he was considered to be ‘below rather than above the average standard of an R.E. officer’.1 He was remembered by his fellow cadets particularly for his aloofness and also for his adherence to High Church rituals.

Before taking up his commission, which was granted to him on 4 January 1871, he travelled to Brittany to spend Christmas at Dinan. His relationship with his father had improved since Ballygoghlan days: the long absences had bound father and son together in a common understanding that grew stronger as the years went by. In all his later letters, Papa gave way to the more jocular endearment Governor. Like many another Victorian father who could not take to his offspring in their childhood days, the colonel began to admire his son’s sturdy independence as he grew into manhood. For his part, Kitchener would have done anything to win his father’s approval. Indeed it was his sense of filial respect that almost ended his career before it began.

The fact that Colonel Kitchener had never seen war service seems to have preyed on his mind, to the extent that he cherished the hope that his son would succeed where he had failed. As France, in that winter of 1870–71, was approaching the end of the disastrous Franco-Prussian War, what better opportunity would there be for his son to throw away the textbooks and see service in the field? Prussia’s tactical superiority, and a complete breakdown in the French system of mobilisation, led to a series of inglorious French defeats culminating in the surrender of the Emperor Napoleon III at Sedan. Two French armies remained in the field, one on the Loire and the other on the Swiss border, but both were largely ineffective. By the beginning of 1871, in spite of spirited resistance in Paris, the war was as good as over – on 18 January Wilhelm I was proclaimed Emperor of Germany in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and by the Treaty of Versailles Alsace and eastern Lorraine were ceded to the new German Empire, thus sowing seeds of discontent that were to be harvested bitterly in the next century.

With his father’s assistance, Kitchener made his way with a fellow cadet, Henry Lawson, to General Chanzy’s army of the Loire, a makeshift force composed largely of reservists and conscripts of uncertain ability and enthusiasm. Earlier that month, on 10 January, it had been in action at Le Mans, an untidy defeat that had seen Chanzy’s men being slaughtered by the new, revolutionary, rifled breech-loading Prussian artillery. Chanzy’s army was attempting to relieve the siege of Paris but the extent of its advance was Laval, and it was there that Kitchener’s war ended. He had been taught the first principles of ballooning at Woolwich and, anxious to put theory into practice, he ascended with an officer in a French artillery balloon without donning proper protective clothing. As a result of a chill caught in the cold upper air he developed pneumonia and pleurisy and Lawson anxiously sent for Colonel Kitchener, who brought him back to Dinan. Had Lawson not acted so judiciously Kitchener’s life could have been lost as he had been placed in a cold and dirty billet long given up by the French. It took him a full year to recover from the effects of the illness.

Many of Kitchener’s contemporaries would have given a year’s promotion to have seen active service but his adventures also attracted the wrath of the War Office. Kitchener’s commission had been granted to him when he was in the process of joining Chanzy’s army and, as a serving officer, he had technically broken the strict neutrality maintained by the British government. Such a violation was open to punishment and, on his return to London, he was ordered to the War Office to answer for his actions to Field Marshal HRH the Duke of Cambridge, cousin to Queen Victoria and Commander-in-Chief of the British Army.

Cambridge was an autocrat who brooked no opposition and he was known to dislike officers who were ‘clever’.2 On this occasion, Kitchener had appeared to be too clever for his own good so, after throwing the rulebook at him, the Commander-in-Chief admonished him with a reprimand, an episode that Kitchener was able to turn to his own advantage later in life in conversation with Lord Esher:

After the armistice and during the peace negotiations he returned to England, when he was sent for by the Duke of Cambridge, then Commander-in-Chief. ‘He called me,’ Lord K. said, ‘every name he could lay his tongue to; said I was a deserter, and that I had disgraced the British Army. I never said a word; and then at the end, the Duke, with a funny sort of twinkle, added, “Well, anyhow, boy, go away, and don’t do it again”.’3

Kitchener’s first posting was to the School of Military Engineering at Chatham, which had been founded in 1812 to provide junior engineer officers with a course of practical training before they joined their units. The Royal Engineers is regarded as a corps d’élite within the British Army and in Kitchener’s day it was generally understood to attract the more intelligent type of officer who, unlike their compatriots in the cavalry or infantry, did not have to purchase their commissions. Engineers had been an integral part of the army since the fifteenth century, when they had been responsible to a Board of Ordnance for the control of the King’s Works and Ordnances. In 1716 an officer corps of engineers was established to command the Corps of Sappers and Miners, an arrangement that lasted until 1787 when the Corps of Royal Engineers was given its Royal Warrant. In 1855 the Board of Ordnance was abolished and the Royal Engineers and the Royal Artillery came under the control of the Army’s Commander-in-Chief.

The courses at Chatham were very much suited to Kitchener as they were practical in nature. He learned the arts of field fortification surveying, submarine mining and estimating and building construction; he was introduced to new-fangled ideas such as electricity, photography and lithography, and he refined his knowledge of ballooning in field tactics. The school was the most advanced of its kind in Europe and the high standard of its courses gave a solid introduction to the role of the Royal Engineers within the British Army.4

Chatham was more to his taste than Woolwich had been, so Kitchener began to rise in the estimation of his instructors and to be noticed as a keen young officer of some promise: his records show a distinct improvement in his military performance. Somewhat to the amusement of his fellow officers he continued to observe High Church rituals, a phase in his life that lasted until 1874 when he joined the English Church Union, established to protect the interests of those churchmen who wanted to continue observing Anglo-Catholic practices within the Church of England. Although, for Kitchener, this was an important moral stance, he was not a bigot and his involvement in the defence of Anglo-Catholicism should be seen against the pattern of his times, the period in which the schism between the Anglo-Catholics and the evangelicals was at its widest in the Anglican Church. At Chatham he became friendly with one of his senior instructors, Captain H.R. Williams, an older man with High Church interests who, like Conder, became a friend and confidant. Kitchener’s friendship with Williams was simple and trusting, based on a ‘never to be forgotten brotherhood of keen Churchmanship’ and, although his friend did not progress beyond the rank of colonel, in the days of his own fame and power Kitchener never forgot that early ‘brotherhood’, often sending Williams keepsakes from his visits abroad.5

Kitchener’s promise brought him the reward of an appointment as ADC to Brigadier-General George Richards Greaves, a member of the War Office staff who had been invited to attend the manoeuvres of the Austrian Army during Easter 1873. Greaves had begun his career as an ensign in the 70th Regiment of Foot (later 2nd East Surrey Regiment) and came from a family with strong military traditions; he was a highly respected officer and Kitchener regarded the appointment as a feather in his cap. When Greaves fell ill on their arrival in Vienna Kitchener had to take his place during the manoeuvres and also at the official functions where, on more than one occasion, he found himself sitting next to the Emperor of Austria–Hungary, Franz-Josef, who as a young archduke had succeeded to the Hapsburg throne in 1848. Such attention rarely came the way of a junior officer but such was the impact that Kitchener made on his hosts that invitations to revisit Vienna were still coming to him in later years.6

His tour of Austria–Hungary ended with an inspection of military bridge-building on the Danube and, on his return to Britain, Kitchener was posted to a mounted troop of the Royal Engineers at Aldershot, which twenty years earlier had been designated the main training garrison in the south of England. Known to generations as ‘The Camp’ or as ‘The Home of the British Army’, it was a large area made up of barrack blocks, parade grounds and training ranges and it was there, in ‘The Long Valley’, that Kitchener put his men of ‘C’ troop through their paces to learn the use of field telegraphy during mock battles. It was there, too, that his knowledge of surveying was perfected to become the useful craft that gave him his first employment.

During the summer Kitchener holidayed in France with his father ‘on the principle of economy’ and while there was introduced to the art of photography, becoming an enthusiastic amateur photographer. He also took the opportunity to discuss his military career with his father. It was not at all certain what he would do next and he dreaded the thought of being sent to India. As he told Millie, he wanted a chance to see action and had therefore volunteered for Major-General Garnet Wolseley’s expedition to the Gold Coast to fight the Ashanti in 1873:

What an age it is since I have written to you and what an age since I have heard from you. You have quite forgotten your duty in not reporting to me the progress of my godson of whom you are in charge. I know you will say it is my fault, sobeit, forgive me. A great swell in a pulpit said, How charming it is to be sinned against because then you can forgive. Now you have the chance. Don’t let it slip and you ought to thank me for it, but I am afraid you won’t write me a line like a good girl to tell me how you are getting on and to show me that you have not quite forgotten you have such an encumbrance as a long-lost brother. Now for news. You know when I left Chatham I was posted to C troop RE. Since that I have been through Dartmoor manoeuvres where we were drenched with rain, then back here field day etc. Lots of work acting adjutant for some time, then the governor came down and paid me a visit which I think he enjoyed. Since that, hunting and work. Saturday last we had a good run and in the evening I dined with Prince Arthur. Was not that grand? Today I rode the Colonel’s horse and had a capital day. You must know I have volunteered for service on the Gold Coast. At least I have said if they order me I shall be glad to go. So the next thing you may hear will be my slaying niggers [sic] by the dozen … Give my love to Harry. When are you coming home? Kiss my godson, he is not yours you know, for me.

The application to join Wolseley came to nothing but the time of inaction came to an end in November 1874. On Conder’s recommendation Kitchener was seconded to the service of the Palestine Exploration Fund, which had been founded, on 22 June 1865, with the object of accomplishing ‘the systematic and scientific research in all the branches of inquiry connected with the Holy Land, and the principal reason alleged for conducting this inquiry [being] the illustration of the Bible’.7