4,49 €

4,49 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Jillian Wayne

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Illustrated Edition — 20 finely curated illustrations

- Includes a crisp Summary

- Complete Characters List

- Concise Author Biography (Sir Walter Scott)

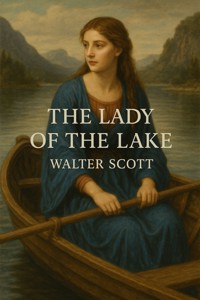

This reader-friendly edition brings the classic to life with 20 evocative illustrations that spotlight pivotal scenes—Ellen Douglas on Loch Katrine, the fierce chieftain Roderick Dhu, and the mysterious hunter who is more than he seems. Designed for modern readers, it comes packed with helpful extras so you can savor the story or study it with confidence.

About the Story

Ellen Douglas, the “lady” of Loch Katrine, shelters with her exiled father among the Highland crags. A lost hunter—James Fitz-James, in truth King James V—finds refuge on her island and falls under the spell of both Ellen and the Highlands’ stern code of honor. Meanwhile, Roderick Dhu, the thunderous chief of Clan Alpine, seeks Ellen’s hand to seal a rising against the crown, while her true love Malcolm Graeme stands in the path of war. Duels, ambushes, clan gatherings, and courtly reckonings surge toward a revelatory climax where kingship meets clemency—and peace is won not by brute force, but by character.

Why You’ll Love This Edition

Accessible & Beautiful: Elegant typography and illustrations make a poetic classic feel vivid and modern.

Perfect for Book Clubs & Classrooms: Built-in summary, character guide, and author bio support deep discussion.

Gift-Ready Classic: A timeless Highland romance with page-turning momentum and cinematic scenery.

Rediscover the poem that helped define Scotland’s image for the world—romantic, rugged, and richly human. The Lady of the Lake endures because it’s more than a tale of clans and kings; it’s a testament to courage, compassion, and the choices that forge a nation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

The Lady Of The Lake By Walter Scott

ABOUT SCOTT

Walter Scott (1771–1832)

Walter Scott—lawyer by training, storyteller by vocation—practically invented the modern historical novel. Born in Edinburgh on August 15, 1771, he survived a childhood bout of polio that left him with a limp and a lifelong habit of long, restorative walks through the Scottish countryside. Those rambles—plus a house full of books and the lore of the Borders—seeded a writer’s imagination with history, landscape, and legend.

Early path: law, ballads, and a poet’s debut

Scott studied at the University of Edinburgh and became an advocate (barrister) in 1792. He never abandoned the legal world: he served as Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire from 1799 and later as Principal Clerk of Session. But his passion was literature. He started as a collector and editor, publishing Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–03), a landmark gathering of ballads that treated folk tradition as living history. His narrative poems—The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), Marmion (1808), and The Lady of the Lake (1810)—made him a literary celebrity.

The invention of “the Waverley novel”

In 1814 Scott shifted from verse to prose with Waverley, published anonymously. It was a sensation. He showed that fiction set in the near or distant past could be both intensely researched and wildly popular. A torrent followed: Guy Mannering, Old Mortality, Rob Roy, The Heart of Mid-Lothian, The Bride of Lammermoor, and, reaching beyond Scotland, Ivanhoe (set in medieval England). These “Waverley Novels” marry brisk plots with social texture—dialect, custom, class conflict—making the past feel inhabited rather than picturesque.

Public figure and nation-brander

Created a baronet in 1820, Scott had a flair for pageantry and reconciliation. He orchestrated King George IV’s 1822 visit to Edinburgh, wrapping the city in tartan and symbolism. Critics later teased the kitsch, but Scott’s project was serious: he used spectacle—and his fiction—to knit Highland and Lowland, Jacobite and Hanoverian, into a shared narrative.

Abbotsford: the house that stories built

Flush with success, Scott built Abbotsford on the River Tweed—part baronial mansion, part museum of Scottish history. It was a working home: he wrote at a punishing pace there, surrounded by armor, relics, and a vast library. When his publishers collapsed in 1826, leaving him with massive debts, Scott refused bankruptcy. Instead, he wrote to repay, producing more novels, a life of Napoleon, and editions of memoirs and chronicles. The workload eroded his health but largely redeemed the debt.

Final years and legacy

Scott died on September 21, 1832, at Abbotsford, and was buried at Dryburgh Abbey. He left an entire genre reshaped: the historical novel as an engine of cultural memory. Beyond literature, he helped fix Scotland’s image in the world's imagination—its speech, songs, and landscapes treated with both romance and reportage.

Why Scott still matters

Form: He set the template for historically grounded storytelling that later novelists—from Tolstoy to Mantel—refined in their own ways.

Method: He fused archival curiosity with popular narrative drive.

Impact: His characters and scenes—outlaws, clans, courtroom reckonings—turned national history into shared myth without abandoning nuance.

Essential works to know: Waverley (1814), Rob Roy (1817), The Heart of Mid-Lothian (1818), Ivanhoe (1819), Kenilworth (1821), plus poems like Marmion (1808) and The Lady of the Lake (1810).

If you want, I can tailor this into a short author bio for a book jacket, or expand it into a classroom handout with discussion prompts.

SUMMARY

The Lady of the Lake — Captivating Summary

Set in the misty Trossachs of the Scottish Highlands, Walter Scott’s narrative poem follows Ellen Douglas, the “lady” who lives with her exiled father on lonely Loch Katrine. When a lost hunter—actually King James V in disguise as “Fitz-James”—stumbles upon her island home, he’s charmed by Ellen’s grace and the Highlands’ fierce code of honor. But Ellen’s heart is already pledged to the noble Malcolm Graeme, while the warlike chieftain Roderick Dhu of Clan Alpine seeks her hand to seal a political alliance.

Across six cantos, Scott braids romance, clan rivalry, and royal intrigue. Roderick rallies the Highlands against the crown; Malcolm is captured; Ellen’s father remains an outlaw; and Fitz-James navigates a land where hospitality is sacred but vengeance is quicker than the claymore. The poem’s pulse quickens through ambushes, duels, and the famous “Gathering of Clan Alpine,” all framed by luminous descriptions of loch, crag, and pine.

In the climax, Fitz-James challenges Roderick; both men reveal courage, but the chieftain falls. Only then does the hunter’s true identity blaze forth—he is King James V. Instead of crushing his enemies, James performs an act of statesmanlike clemency: Ellen’s father is pardoned, Malcolm is freed, and Ellen’s steadfast love is rewarded. The Highlands’ storm settles into a hard-won peace.

Why it captivates

Scenery as character: Scott turns the Trossachs into a living stage—echoing horns, flickering torchlight, and mirror-black water heighten every choice the characters make.

Honor vs. love: Ellen’s loyalty and Roderick’s iron clan duty collide with the king’s justice, giving the poem its moral torque.

Pageantry & pace: Battle chants, courtly rituals, and swift adventure scenes feel cinematic long before cinema existed.

Quick character guide

Ellen Douglas: Poised, principled heroine whose compassion never wavers.

Fitz-James (James V): A king learning his people by walking among them.

Roderick Dhu: Charismatic, fearsome Highland chieftain—honorable even in enmity.

Malcolm Graeme: Ellen’s true love; a gentler ideal of Highland courage.

Sir Douglas: Ellen’s father, whose outlawry drives the political stakes.

Themes to notice

Mercy as strength: The king’s clemency resolves conflicts brute force can’t.

Nation-making: Scott imagines a Scotland where Highland pride and royal law can coexist.

Nature’s moral mirror: Weather and landscape echo inner turmoil and resolution.

Legend and identity: Ballad rhythms and clan lore shape how people see themselves.

Want this turned into a one-paragraph jacket blurb, or a classroom handout with key passages and discussion questions?

Contents

Canto First. The Chase

Canto Second. The Island

Canto Third. The Gathering

Canto Fourth. The Prophecy

Canto Fifth. The Combat

Canto Sixth. The Guard-room

Canto First

The Chase

I

The stag at eve had drunk his fill, Where danced the moon on Monan's rill, And deep his midnight lair had madeIn lone Glenartney's hazel shade; But when the sun his beacon redHad kindled on Benvoirlich's head,The deep-mouthed bloodhound's heavy bayResounded up the rocky way,And faint, from farther distance borne,Were heard the clanging hoof and horn.

II

As Chief, who hears his warder call,'To arms! the foemen storm the wall,'The antlered monarch of the wasteSprung from his heathery couch in haste.But ere his fleet career he took,The dew-drops from his flanks he shook;Like crested leader proud and highTossed his beamed frontlet to the sky;A moment gazed adown the dale,A moment snuffed the tainted gale,A moment listened to the cry,That thickened as the chase drew nigh;Then, as the headmost foes appeared,With one brave bound the copse he cleared,And, stretching forward free and far,Sought the wild heaths of Uam-Var.

III

Yelled on the view the opening pack;Rock, glen, and cavern paid them back;To many a mingled sound at onceThe awakened mountain gave response.A hundred dogs bayed deep and strong,Clattered a hundred steeds along,Their peal the merry horns rung out,A hundred voices joined the shout;With hark and whoop and wild halloo,No rest Benvoirlich's echoes knew.Far from the tumult fled the roe,Close in her covert cowered the doe,The falcon, from her cairn on high,Cast on the rout a wondering eye,Till far beyond her piercing kenThe hurricane had swept the glen.Faint, and more faint, its failing dinReturned from cavern, cliff, and linn,And silence settled, wide and still,On the lone wood and mighty hill.

IV

Less loud the sounds of sylvan warDisturbed the heights of Uam-Var,And roused the cavern where, 't is told,A giant made his den of old;For ere that steep ascent was won,High in his pathway hung the sun,And many a gallant, stayed perforce,Was fain to breathe his faltering horse,And of the trackers of the deerScarce half the lessening pack was near;So shrewdly on the mountain-sideHad the bold burst their mettle tried.

V

The noble stag was pausing nowUpon the mountain's southern brow,Where broad extended, far beneath,The varied realms of fair Menteith.With anxious eye he wandered o'erMountain and meadow, moss and moor,And pondered refuge from his toil,By far Lochard or Aberfoyle.But nearer was the copsewood grayThat waved and wept on Loch Achray,And mingled with the pine-trees blueOn the bold cliffs of Benvenue.Fresh vigor with the hope returned,With flying foot the heath he spurned,Held westward with unwearied race,And left behind the panting chase.

VI

'T were long to tell what steeds gave o'er,As swept the hunt through Cambusmore;What reins were tightened in despair,When rose Benledi's ridge in air;Who flagged upon Bochastle's heath,Who shunned to stem the flooded Teith,--For twice that day, from shore to shore,The gallant stag swam stoutly o'er.Few were the stragglers, following far,That reached the lake of Vennachar;And when the Brigg of Turk was won,The headmost horseman rode alone.

VII

Alone, but with unbated zeal,That horseman plied the scourge and steel;For jaded now, and spent with toil,Embossed with foam, and dark with soil,While every gasp with sobs he drew,The laboring stag strained full in view.Two dogs of black Saint Hubert's breed,Unmatched for courage, breath, and speed,Fast on his flying traces came,And all but won that desperate game;For, scarce a spear's length from his haunch,Vindictive toiled the bloodhounds stanch;Nor nearer might the dogs attain,Nor farther might the quarry strainThus up the margin of the lake,Between the precipice and brake,O'er stock and rock their race they take.

VIII

The Hunter marked that mountain high,The lone lake's western boundary,And deemed the stag must turn to bay,Where that huge rampart barred the way;Already glorying in the prize,Measured his antlers with his eyes;For the death-wound and death-hallooMustered his breath, his whinyard drew:--But thundering as he came prepared,With ready arm and weapon bared,The wily quarry shunned the shock,And turned him from the opposing rock;Then, dashing down a darksome glen,Soon lost to hound and Hunter's ken,In the deep Trosachs' wildest nookHis solitary refuge took.There, while close couched the thicket shedCold dews and wild flowers on his head,He heard the baffled dogs in vainRave through the hollow pass amain,Chiding the rocks that yelled again.

IX.

Close on the hounds the Hunter came,To cheer them on the vanished game;But, stumbling in the rugged dell,The gallant horse exhausted fell.

The impatient rider strove in vainTo rouse him with the spur and rein,For the good steed, his labors o'er,Stretched his stiff limbs, to rise no more;Then, touched with pity and remorse,He sorrowed o'er the expiring horse.'I little thought, when first thy reinI slacked upon the banks of Seine,That Highland eagle e'er should feedOn thy fleet limbs, my matchless steed!Woe worth the chase, woe worth the day,That costs thy life, my gallant gray!'

X.

Then through the dell his horn resounds,From vain pursuit to call the hounds.Back limped, with slow and crippled pace,The sulky leaders of the chase;Close to their master's side they pressed,With drooping tail and humbled crest;But still the dingle's hollow throatProlonged the swelling bugle-note.The owlets started from their dream,The eagles answered with their scream,Round and around the sounds were cast,Till echo seemed an answering blast;And on the Hunter tried his way,To join some comrades of the day,Yet often paused, so strange the road,So wondrous were the scenes it showed.

XI.