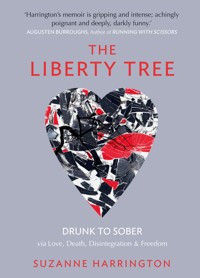

8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Suzanne Harrington did all the things that adults do, long before she'd grown up: met Leo, married, had babies. She also partied, was homeless for a while, and drank - and drank. She headed towards disintegration, with Leo at her side, locked deep in himself. Then, waking to the wreckage of yet another lost weekend, she stopped drinking - and Leo, her companion and enabler, became a stranger. They separated. Newly sober, and freed from her demons, Suzanne embraced life. Leo chose escape. Early one morning the police arrived. A body had been found hanging from a tree. When it was all over, and Suzanne had buried Leo, and helped her children to grieve, she sat down and wrote the story of their father's life. This is for them. It is for the memory of Leo. It is also for anyone who has partied too hard, found life unbearable, avoided the truth. It is like nothing you have read before, or will read again. It is touching, hilarious, brutally honest and utterly compelling.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

THE LIBERTY TREE

Published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Suzanne Harrington, 2013

The moral right of Suzanne Harrington to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Extract from ‘Vers de Société’, The Complete Poems by Philip Larkin, reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd. Extract from The Beach by Alex Garland, reprinted by permission of Andrew Nurnberg Associates. Extract from Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh, published by Secker & Warburg, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Limited.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 9780857899415 E-book ISBN: 9780857899422

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Leo, for all that he gave.

‘You see that stunted, parched and sorry tree? From each branch liberty hangs. Your neck, your throat, your heart are all so many ways of escape from slavery...’

SENECA

CONTENTS

7 September 2006

PART ONE

Seven years, two months, seventeen days

1 London

2 Halloween

3 Brighton

4 India

Intermission

5 Brighton

6 Birth

7 ‘Not signed to avoid delay’

8 Christmas

PART TWO

7 September 2011 – five years later

9 Sober

10 Full Moon Lunar Eclipse

11 The Memory Box

Epilogue

7 SEPTEMBER 2006

It’s one of those early summer mornings when the sun and the moon are in the sky together, the moon’s fullness fading to a thin silver sliver as the strong light rises. The sea is flat and calm and glittering. Everything is fresh. Along the seafront, the white houses stand grandly like wedding cakes, blinding white in the sunlight. The empty beach stretches west, deserted except for the solitary dots of dog walkers, their faraway dogs leaping into the rush and suck of the tide, chasing tiny sticks. A lone truck collects rubbish from the beachfront bins.

From the top of the hill you can see the pier jutting into the glitter, its fairground hovering on tiny black metal matchsticks over the water. The helter skelter, the ghost train, and the roller-coaster are all still and silent in the distance, the lights and music off, the wooden boardwalk empty. Everything is pale blue, gold and silver. The whole morning is illuminated with fresh, clean light. Its newness dazzles.

A mile or so east of the pier, the town ends where the soft hills roll down to the sea. You can see miles of coast from up here, the town laid out below like an architect’s model, spreading west and blurring into the next town. Up here, there is nothing except wind and air and huge sky. A few trees hunch like old women caught in a gale, their leaves and branches angled permanently inland by the sea winds. The grass is short and soft, and bright with wild flowers.

There is a dip in the hills where some trees have grown straight and tall, protected by the side of the hill; it is a place to hunch down and smoke a cigarette away from the wind. There are a few old cider bottles amongst the brambles, their labels faded, and a blackened patch on the ground where fires have been lit. A plastic crisp wrapper flaps in the tangle of thorns.

And hanging from a tree in this sheltered dip, up here on the windswept hill, is a body. It swings very gently in the breeze, feet not far from the ground, a blue nylon rope cutting into the neck. The head is at an unnatural angle, the tongue bulging and blue. The face is bluish too, blue like Lord Shiva. A small rucksack has been kicked away, and a mobile phone lies switched off, face down in the earth. The body has been hanging here for a while now, since the moon was at its highest and brightest last night. It is already stiff.

Nobody has found it yet. No dog has come bounding through the dip, in a frenzy of sniffing and barking. No rider has cantered up the hill and wheeled their horse around after seeing the sway of its silhouette. No lone morning runner has glanced this way and seen its terrible stillness. Not yet. It’s still too early. In another few hours, police will be knocking on a door, watching impassively as faces collapse. But for now, the body is just hanging there, stiff and silent and alone in the soft bright morning.

PART ONE

‘You can only write what you know, even if you don’t know that you know it.’

WILLIAM BURROUGHS

SEVEN YEARS, TWO MONTHS, SEVENTEEN DAYS

Since your father liberated himself on that sorry tree branch, he has faded away. There is a photograph of him in each of your bedrooms – in a Stetson and red and black fringed cowboy shirt at Gay Pride, and in a swirly psychedelic shirt, necklace and Lennon glasses walking behind two women dressed as Blue Meanies at the Children’s Parade, at the start of the Brighton Festival. He looks great in those photos – bright and alive. He was always good at dressing up. In that respect he was a bit of a show-off, a bit fabulous, which I always found attractive. He wasn’t the kind of man who would slob out in knobbly grey tracksuit bottoms and a baggy top. Not until nearer the end, but that’s still some way off.

There’s another photo of him in a tight sparkly silver t-shirt and a horned devil’s hat handmade from red cotton, pushing one of you through the mud another year at Pride, with Petula Clark singing in the background and me posing next to him, fat from pregnancy in a bright blue African muumuu, clutching a parasol. There’s a jacket of his in your wardrobe – outrageous pink plush, a girl’s jacket that he used to wear clubbing with his big chunky boots and black snakeskin jeans. He was a bit of a disco king, your dad. He loved it.

But we don’t really talk about him so much anymore, do we? It’s hard to know just how gaping the dad-sized hole in your lives is. It’s hard to know how it will all turn out.

Yesterday you were complaining, high on pick’n’mix, after some garish 3D Disney film at the cinema, how predictable the story always is – a princess, a hero on a horse, a quest, a castle, a happy ever after. Why can’t it be more realistic? you said. Why can’t they die in the end? Or at least one of them? Because, I said, people think that kids can’t handle stuff like that. And the two of you scoffed and said rubbish, of course they can. You’re right, of course. It’s the adults who can’t.

Anyway. You’ve dealt with a dead dad, but you still don’t know the full story. Neither do I, other than how and when he died. I still don’t really know why, but I knew him a bit longer than you – although not that much longer. You were five and three when he died, but I only knew him for seven years, two months and seventeen days. Even if I had known him longer, I doubt I would ever have really known him, because he was like a magic mirror: he reflected back to you only what you wanted to see.

He was the kind of man who would have brought a suitcase on a camping trip. He knew how to eat lobster, but not how to pitch a tent. He had been on lots of holidays, but never travelled. He could link up a network of computers, but had not the faintest idea how to ride a bike or drive a car. He could cook, but only with a cookery book, and only certain dishes – so he could make a splendid lemon drizzle cake, but could never just throw a meal together. If fenugreek was a listed ingredient and he didn’t have any, the curry remained unmade. He was not big on improvisation or thinking on his feet. He was a whizz with wires, but had no idea how to do anything with wood. He had great skin, and fabulous teeth.

So although I don’t know his story, this is the story of me and him, and our seven years. You may not like it much, because it will tell you things you may not want to know, and neither he nor I may come across terribly well, although how you read it is really none of my business. But better honesty than a pretty story. It would be lovely to write you a heart-stirring tale of heroes and bravery, of selflessness and compassion, but instead you’ll be reading the story of a suicide written by a drunk. Only you can make your own happy ending.

Just remember – this is a story that is filtered through me. His version would have been different, but he’s not here, so this is the only version you’re going to get. It is my truth, which is not necessarily the truth. But is there ever any such thing as the truth? I doubt it.

1 LONDON

We met at a party in New North Road in Islington in June 1998. Not the kind of party youre thinking of there wasnt any food, and nobody brought a present. It was a big house that seemed like a squat even though it wasnt big dark rooms empty of furniture and full of people and noise. Staircases crowded, strobe lights in the basement, bodies everywhere. It was all very minimal and functional, the music semi industrial. The doof-doof-doof of techno. Gabber drilling in the basement that mutant strain of dance music that made your ears bleed, undanceable at 160 bpm, like a kanga hammer inside your head. I was never a handbag house kind of girl I liked my music fast and hard but gabber was ridiculous. Your dad loved it.

That night was my first night out in the city for ages. In any city. For three months I had been moving between remote beaches around South East Asia, where the drugs were few and mellow (apart from at the end, on Koh Phangan where we had acid and tooth-splintering Thai speed pills at a full moon party on the beach at Haad Rin), and so I believed myself to be shiny and clean of brain and body after my three months away from London parties. I wasnt at all my brain chemistry was extremely precarious, like a dodgy lab experiment just waiting to blow, although I didnt know that at the time. I had no idea that years of cumulative hedonism was doing my head in. How could I have? Besides, I was feeling really good. This meant good on the surface, because the surface was tanned and backpacker-slim and bleached on top. The night I met your dad, I was a blonde, with an orange bindi on my forehead, wearing an orange furry bikini top with a zip down the front, and orange Thai fishermans trousers that made peeing complicated. I looked like a traffic cone with a tan. In a good way, of course.

I suppose I might have been on the pull. It wasnt conscious. Nothing ever was with me. It happened when I was lying on a giant floor cushion, being softly swallowed and devoured by my first pill in months. It dissolved me into benign mush and I was breathing in and out, in and out, eyes half closed, lost in the huge pleasure of it. Its not called ecstasy for nothing. I was inside a huge, beautiful softness.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!