Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

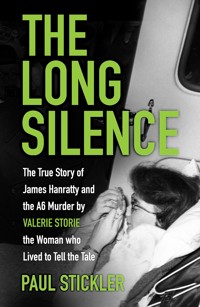

In August 1961, 22-year-old Valerie Storie and 36-year-old Michael Gregsten were the victims of James Hanratty in the notorious 'A6 Murder'. After a five-hour ordeal, ending in a layby on the A6 in Bedfordshire, Michael was shot dead and Valerie was raped, shot and left for dead. She survived, but was paralysed and remained in a wheelchair until her death in 2016. In 1962, Hanratty became one of the last men in the UK to be hanged, unleashing forty years of fierce and passionate debate, as many were convinced of his innocence, until 2002 when DNA evidence proved that he was indeed guilty. Valerie, however, was never in any doubt, and picked out Hanratty in an identity parade. She always intended to write a book, and over the years had secretly drafted its contents and written hundreds of notes. Yet for over thirty-five years she gave no interviews, despite persistent media pressure to do so. The Long Silence is, in essence, Valerie's posthumous autobiography, explaining for the first time every explicit detail of the 'cat and mouse' drive, as Michael and Valerie tried on over twenty occasions to deter and thwart the apparently indecisive Hanratty.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 535

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Paul Stickler, 2021

The right of Paul Stickler to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9826 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

‘Dedicated to the memory of my beloved parents and all the many friends who held faith with me’

Valerie Jean Storie1938–2016

‘You dream, and very rarely, you are not in a wheelchair.’

Valerie Jean Storie

Contents

Foreword by Professor Adrian Hobbs CBE

Acknowledgements

The Protagonists

Introduction

Part 1 – The Crime

Chapter One – Valerie and Michael

Chapter Two – The Cornfield

Chapter Three – On to the A6

Chapter Four – Clophill

Part 2 – The Investigation

Chapter Five – The First Two Weeks

Chapter Six – The Vienna Hotel

Chapter Seven – Enter James Hanratty

Chapter Eight – Under Arrest

Chapter Nine – Liverpool

Chapter Ten – Committal

Part 3 – The Trial

Chapter Eleven – Valerie’s Evidence

Chapter Twelve – Prosecution Witnesses

Chapter Thirteen – The Case for the Defence

Chapter Fourteen – Cross-Examination

Chapter Fifteen – Defence Witnesses

Chapter Sixteen – The Jury’s Deliberation

Part 4 – The Aftermath

Chapter Seventeen – Betrayal and Silence

Chapter Eighteen – The Gathering Storm

Chapter Nineteen – The Campaign Continues

Chapter Twenty – The Final Judgement

Chapter Twenty-One – The Final Years

Epilogue – So, What Really Happened?

Bibliography

Notes

Foreword by Professor Adrian Hobbs CBE

Valerie Storie witnessed the murder of her boyfriend, Michael Gregsten; was shot and critically injured; saw the culprit convicted; and then expected to disappear from the public eye. It was not to be. For most of the rest of her life, she was pestered by the media and vilified for causing the conviction and hanging of James Hanratty. A pressure group was set up, books were written, television programmes produced and debates in parliament were held to support this false claim.

When, eventually, enhanced DNA techniques showed that Hanratty was indeed guilty, Valerie decided to write a book telling the true story. Although she started to write notes, the book was never completed. However, she had retained a comprehensive collection of material. This included transcripts of the police interviews and the trial, all of the published books, official reports, a comprehensive set of newspaper cuttings, scripts and recordings of television programmes and correspondence related to the case. It seemed important to ensure that her ‘papers’ were retained for future research into the case.

When he learnt of the papers, Paul Stickler expressed an interest in writing what could have been Valerie’s book. Having processed all of the available material, both Paul and I were determined to ensure that the book was as factually correct as possible. It is almost an unbelievable story and a fascinating read. Fact can truly be stranger than fiction.

Acknowledgements

I owe a great deal of gratitude to Professor Adrian Hobbs CBE, friend and work colleague of Valerie Storie, without whom this story could not have been written. As executor to her will, he generously allowed me access to Valerie’s papers in order that an account of her ordeal could be written. As a result, we are now very much more enlightened about the shocking events which occurred between 1961 and 2016.

I also wish to express my grateful thanks to David Sanders, Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of Sunderland who not only provided invaluable support to me in reading the script and making many suggestions to help improve the narrative but also in providing expert advice and guidance in my attempt to interpret the personality traits of James Hanratty. I am very grateful for his time. I would also like to thank Chief Constable Garry Forsyth of Bedfordshire Police who kindly allowed me access to the archived case papers in order that I could corroborate newspaper reports, earlier narratives and details recorded by Valerie.

Finally, a personal thank you to Mark Beynon, National Commissioning Editor at The History Press, for agreeing to publish the manuscript and to my literary agent, Robert Smith, for all his constructive advice throughout the research and writing process.

The Protagonists

Acott, Basil (Bob) Montague

Detective Superintendent in charge of murder investigation

Alphon, Peter Louis

‘Suspect’ in murder investigation

Blackhall, Edward

Key witness to driving of Morris Minor

Dinwoodie, Olive

Liverpool sweet shop assistant

Durrant, Frederick

Alias of Peter Alphon

Evans, Terry

Fairground worker in Rhyl

Ewer, William

Janet Gregsten’s brother-in-law

Foot, Paul

Journalist

France, Carol

Daughter of Charles France

France, Charles (Dixie)

Friend of James Hanratty

Gillbanks, Joseph

Defence enquiry agent for James Hanratty

Glickberg, Florence

Alias of Florence Snell. Employee at Vienna hotel

Glickberg, Jack

Alias of William Nudds. Employee at Vienna hotel

Gregsten, Janet

Wife of Michael Gregsten

Gregsten, Michael

Murder victim

Hanratty, James

Convicted of the murder of Michael Gregsten

Hawser, Lewis

QC in charge of 1975 review

Hirons, Harry

Petrol pump attendant

Jones, Grace

Landlady of Ingledene guest house, Rhyl

Justice, Jean

First author of book on Hanratty and friend of Peter Alphon

Kerr, John

First witness to speak to Valerie Storie after she had been shot

Kleinman, Emmanuel

Solicitor for James Hanratty

Nimmo, Douglas

Detective Chief Superintendent in charge of review of Rhyl alibi

Nudds, William

Employee in Vienna hotel

Oxford, Ken

Detective Sergeant, assistant to Bob Acott

Rennie, Ian

Physician in charge of Storie’s care

Sherrard, Michael

Hanratty’s defence counsel

Skillett, John

Key witness to driving of Morris Minor

Snell, Florence

Employee in Vienna hotel

Storie, John (Jack)

Father of Valerie

Storie, Marjorie

Mother of Valerie

Storie, Valerie

Victim of the A6 attack

Swanwick, Graham

Prosecuting counsel

Trower, James

Key witness to driving of Morris Minor

Woffinden, Bob

Journalist and film producer

Introduction

Many people will recognise the name James Hanratty. He was hanged in April 1962, at the age of 25, having been convicted for what became known as the A6 murder. On a summer evening in August the previous year, he held a couple at gunpoint in a cornfield in Buckinghamshire after he had surprised them while they were sitting in their Morris Minor car. After keeping them captive for almost two hours he ordered them to drive under his directions through Middlesex on the outskirts of London and then north along the A6 towards Bedford. After a journey of around 60 miles, and having kept his two captives imprisoned for five hours, he shot the man in the head, raped the woman and finally emptied a number of rounds from his revolver into her body. Miraculously, despite one bullet penetrating her neck, she survived. The 22-year-old would be paralysed from the chest down for the rest of her life.

Hanratty would be convicted after a trial lasting almost four weeks but his execution marked the beginning of a forty-year journey of cries of a miscarriage of justice, media frenzies, legal arguments, criticism of the police, a referral to the Criminal Cases Review Commission and finally a Court of Appeal ruling in 2002 when DNA evidence would finally put an end to the furore; he was indeed guilty.

For many, that was the final curtain and nothing more needed to be said. Yet, among all the controversy, the newspaper articles, the television programmes and the books published that had begged for an overturning of the conviction, one person remained silent. She kept her counsel. She had been pilloried by the media for decades for sending an innocent man to the hangman’s noose. Journalists had banged on her door for thirty-five years hoping to get the woman to break her silence, but she remained steadfast.

That person was the woman who witnessed her partner being shot at point-blank range while sitting in the front seat of his car. That person was the woman who was then raped alongside his dead body, who was then made to drag him along the road and was finally on the receiving end of a volley of bullets. That person was Valerie Storie. She gave evidence at Hanratty’s trial but then withdrew from the limelight. From the confines of her wheelchair she read every written word, watched every television programme, making note after note.

When Hanratty’s guilt was confirmed through DNA, she decided the time had come to write her own story. The personal story of how she came to be on the wrong end of a revolver, on the receiving end of a rapist’s attentions, shot and left for dead. How the newspapers continued to hound her, to criticise her and to finally give up on her when the truth finally emerged. How she tried to live a normal life, her courage and the incredible fight against how her life had been turned upside down in August 1961.

Yet, she never wrote it; a few outline sketches of her memories she wanted people to know and hundreds of handwritten notes containing her thoughts gathered dust in her home, but it was not the full story. She died in 2016, her innermost feelings littered among the piles of paper upon which she had scribbled.

But now the story is told from her perspective; an account that places her at the heart of a murder hunt, the trial of a killer and its aftermath. The Storie Papers that have now come to light contain detail that never reached the courtroom or the journalists’ pens; information that, though known at the time, was never brought out at the trial as it had no bearing on the identity of the killer. The words you will read are those that passed Valerie’s lips and with no creative re-enactment. What the Storie Papers reveal are her personal experiences and her hopes and dreams as a young woman, all of which were, literally, shot away from her.

Left for dead in an isolated layby on the side of the A6, her body now paralysed, she remained sufficiently lucid and attentive to be able to relay the story from the initial kidnap through to the five-hour journey, the killing, the rape and the final attempt to silence her. Her story could have ended there, but it was only the beginning. She would be resolute in her recollections and underwent strong cross-examination at her attacker’s trial about how she was wrong in her identification of the killer. Afterwards, many claimed, it was she who had sent an innocent man to the gallows.

After Hanratty was executed, her public abuse would continue for another forty years as repeated attacks were levelled at her and the police for malpractice. A self-appointed ‘A6 Committee,’ headed by a leading journalist and supported by an overzealous barrister, would, year after year, subject her to more and more pressure. Unsolicited journalists would visit her front door, questions would be raised in the Houses of Parliament and separate investigations into discrete aspects of the case would occupy the front pages for years to come.

In the meantime, Valerie tried to rebuild her life. She returned to work and she would refer to the events of 22 August 1961 as her ‘accident’. Her parents, who cared for her, died. Yet still the headlines kept coming. Hanratty was innocent. Storie was mistaken. The police were corrupt. And because her partner was still in the process of separating from his wife at the time of his murder, she would receive letters at home saying she was a whore, a tramp and an adulteress. But in the face of adversity, she kept smiling and despite more newspaper articles claiming the police had got it wrong and the case referred to the Court of Appeal, she never doubted herself.

For forty years, she would remain in touch with the police officers who investigated the events of that August evening; police officers who were maligned and accused of being inept and incompetent and who had managed to let the real killer slip through their fingers. Many areas of the investigation were repeatedly cited as clear evidence of a police cover-up and the British psyche would become conditioned around a myth that grew into reality; those officers too, maintained a dignified silence.

Much of the fine detail has not been included in this account. To do so would detract from Valerie’s experience of four decades of torment but critical aspects, which kept the story alive for forty years, are explained. It addresses criticisms aimed at Valerie, the police, the judiciary and the government and offers a different view.

When the courts finally confirmed Hanratty’s guilt in 2002, Valerie’s feelings were of sorrow for his family. His parents, she said, had gone to their graves not knowing the truth. She wanted the world to know the other side of the story and she picked up a pen and started to sketch out her thoughts.

She had remained silent for thirty-five years. Her book, she decided, would be called The Long Silence. But her jottings would lie in a cardboard box – until now. After her death in 2016, her friend and former work colleague, Professor Adrian Hobbs, was kind enough to release the papers in order that Valerie may realise her ambition and offer her own account.

It is time for her story to be told.

PART 1 – THE CRIME

Chapter One

Valerie and Michael

‘Goodbye. I shan’t be late.’1

These were the words called out by 22-year-old Valerie Storie to her parents on 22 August 1961 as she stepped out from her house in Anthony Way, Cippenham, on the western outskirts of Slough. She closed the door and followed Michael Gregsten to the grey Morris Minor parked on the small driveway of the semi-detached house in which she had been born. It had been a relaxing evening so far. Michael, dressed smartly in a jacket, shirt and tie, had taken time off from work that week but had collected Valerie from where they were both employed at the nearby Road Research Laboratory in Langley. They stopped briefly for him to have a haircut and then drove on to her parents’ house for tea.

Marjorie and Jack Storie doted on their only child. She was bright, engaging and enjoyed life; to them, the perfect daughter. She had always been a bit of a bookish child although, to the horror of her teachers, she left Slough Grammar School at the age of 16, unwilling to go to university, but she was strong in character and liked to make her own decisions.

The job at the laboratory was her first and she loved being involved in the roadside experiments they carried out to identify causes of road accidents and, perhaps unsurprisingly, had developed a passion for motor cars. Better still, her role even required her to drive from time to time. With her steady wage of £34 a week,2 she enjoyed the occasional holiday and ventured off to places such as Sweden, Austria and, more recently, Majorca.

The man she had brought home for tea was a physicist and both Marjorie and Jack knew that the two of them shared a passion for motor rallying and that they had agreed to arrange some sort of work event for the coming weekend. As far as they were concerned, their daughter and Michael were now heading off back to the laboratory to put the final piece of the plan together.

The reality was somewhat different.

Michael and Valerie had known each other for some time, having met at work at the rather mundane canteen committee where social functions were discussed. Over time, the pair had become attracted to one another, but beyond that, it was true that their shared passion was motor rallying and they had agreed to take on the responsibility for organising navigational rallies for club members. It was their plan that evening to drive to a nearby public house and, over a drink, make some final alterations to the event in Chesham that coming weekend.

The relationship, though, was complicated. Michael was fourteen years older than her and married with two children, though he was now in the process of separating from his wife, the probable reason why she chose not to discuss it with her parents. Valerie had been brought up in a very respectable, conservative household and for her to have a relationship with a man who was still married would have been difficult for them to understand. But Valerie found Michael ‘dashing and handsome’3 and would later say that, ‘I suppose I was flattered that he took a shine to me.’ In the four years that they had known each other they had grown closer and were now ‘very fond of one another’. They had been sexually intimate for two years and, seemingly, marriage had been mentioned.4 In reality, this was Valerie’s first serious relationship; tragically, it would also be her last.

The Morris was Michael’s aunt’s car but she had recently given it to him due to her advancing blindness and the two of them had adapted it to their own tastes. It was quirky. The radio button was permanently stuck in the ‘on’ position and a home-made wireless aerial was fixed to one of the rear windows. They had attached reflective Scotch tape on the rear bumper to make it more visible in the dark. Valerie had stuck a white flower-holder to the inside of the windscreen in which she had placed small, pink, artificial flowers and miniature roses. The exhaust pipe leaked, a small point that would soon become a prominent feature in the few hours that lay ahead, but it was their car. They knew its intricacies. They had rallied together in it, Michael as the driver, Valerie the navigator. They had made love in it. It was special to them and captured their personal love of driving. It was their world and one that had made the friendship grow into something ‘a little deeper’.5

The Station Inn at Taplow was a short drive away. They arrived around half past seven and people who recognised them said that they kept themselves to themselves, Michael drinking a single pint of Double Diamond beer, Valerie, a gin and Pepsi Cola. They discussed the rally, studied maps – this was Valerie’s forte – and agreed the route and the clues they would give to the competitors. In practice, the rallies amounted to little more than treasure hunts carried out by car fans following various clues set down by the organisers, but it was fun. At work she visited various accident sites and over the years she had not only become a competent driver but she was somewhat of an authority on road names and numbers, and her sense of direction had become very acute.

Just over an hour later, around 8.45 p.m., they finished their drinks, returned to their car and set off. Michael drove; Valerie sat in the passenger seat.

They were not yet ready for home though. They had matters they needed to talk about, not least Michael’s imminent move from his accommodation in Windsor to new rooms in Maidenhead sometime later that week. Both he and Valerie had already been to see the house and Michael had paid a week’s rent in advance; the landlord recalled being introduced to Valerie as Michael’s fiancée. Only the evening before, he had finalised the arrangements and been given the front door key. Everything seemed to be set up for the two of them spending their immediate futures together.6

Michael, though, was a bit of a worrier. He was concerned about money, his wife, his two children who he idolised and more generally about his own mental well-being. His marriage had been a bit difficult and the world had seemed to be turning in on him but now he was about to embark upon a new chapter in a new home. He needed to talk and having driven away from the pub forecourt they set off for the secluded spot they used sometimes when they wanted privacy; a cornfield in nearby Dorney Reach. It was less than 2 miles away.

There were houses in the area but this was mostly quiet countryside, even though only a few hundred yards from the newly built M4 motorway. No one could have known they were there or had planned to travel there as it had been a last-minute arrangement. Valerie would later say: ‘If we hadn’t been doing a rally for the laboratory, trying to plan a rally-cum-treasure hunt, we would not have been there at that time.’7

Michael drove the Morris no more than 6ft into the field, the car still clearly visible from the road. He extinguished the lights and switched off the engine. They were alone, nervously excited about the future, and started to talk.

Chapter Two

The Cornfield

Valerie’s shopping basket rested on the back seat. It was full of her personal effects including her handbag, a wallet and a purse, a few pound notes and coins pushed inside them. Michael’s duffel bag containing freshly laundered clothing rested next to it. A brown, check car rug was spread out; another small, personalised feature of the rallying Morris.

They had been here on a few occasions before, to make love or simply to spend time alone together. But tonight, they were talking. They had finished the planning for the weekend’s rally, Valerie’s maps folded away in her shopping basket. What was going to happen to them? Were they to marry? Was Michael actually going to leave his wife and two boys? Where was the money going to come from? He was a scientist at the laboratory and being a talented mathematician occasionally taught evening classes at St Albans Technical College, so extra money was coming in, but it nevertheless worried him. With some justification it seemed, since Michael had a tendency to spend willingly rather than save.

They were, though, generally relaxed talking in their cornfield. They had never been disturbed before and it was easier to talk here rather than anywhere else. They kissed only once. How much time had passed since they had pulled into the field is not absolutely clear since neither was paying particular attention but, Valerie would later estimate, after about thirty minutes their private conversation was disturbed. The two were facing each other, their arms resting on the backs of the seats as they spoke quietly when there was a tap on the driver’s window.

Valerie’s immediate instinct was that it was the farmer coming to find out what they were doing and to tell them to get off his land. It was not yet dark, but twilight had set in and visibility was not perfect. Michael wound down his window, only halfway, when a gun was thrust through the gap, its muzzle pointing directly at them.

‘I’m a desperate man. This is a hold-up,’ a man’s voice said.

What Valerie then saw surprised her. The man was immaculately dressed. Through the window of the car and despite the fading light, she could clearly see that he was wearing a suit and tie with a white shirt. She was able to see only the body of the man between his waist and shoulders, but his smart appearance seemed at odds with his threatening behaviour. The sudden intrusion did not seem real. None of it made sense.

With the gun still pointing at them, the man said, ‘I have been on the run for four months. If you do as I tell you, you will be alright.’

He demanded the driver hand over the ignition key.

Michael turned to remove it from the ignition but, in what proved to be a recurring feature of the hours that lay ahead, Valerie’s force of character, perhaps even a hint of stubbornness, took over. Whether it was because she was in shock or perhaps still not believing this was really happening – she would never be sure – she was determined that this man, whoever he was, was not going to take advantage of them. She mumbled to Michael not to hand over the key and grabbed his hand to stop him. Michael reacted: ‘Don’t be silly. He’s got a gun.’

The muzzle of the gun inches away from their heads reinforced the point and Valerie held back. Michael passed the key through the open window.

Fear now set in. The man was real. The gun looked real. Opening the rear door on the driver’s side, the gunman climbed into the back, Valerie instinctively gathering her basket to make sure it was safe from the man’s clutches. Now settled inside, he ordered Valerie to lock all the doors from the inside, telling them both not to look round but face the front. She recalled later how she remembered her reaction: ‘I didn’t scream. I sometimes wonder why I didn’t. This is daft. I must be asleep.’1 Before getting into the car, she remembered the man locking the driver’s door from the outside and he now instructed Michael to lock the rear one he had just clambered through. He clearly did not wish to be surprised by anyone walking past.

With the man now sitting inches behind them, the weapon pointing in their direction, Valerie feared the worst and instinctively grabbed the hand of the man with whom she had started to plan her future. They looked at each other.

‘What are we going to do?’ she whispered.

Michael’s response was terse.

‘I don’t know.’

Seemingly content he had everything under control, the gunman started talking. A young, cockney accent, Valerie thought. ‘I’m a desperate man,’ he repeated. Every policeman in Britain was looking for him, he claimed. He hadn’t eaten for two days and he’d been on the run for four months. As he spoke, Valerie and Michael listened, their heads slowly turning towards the man wielding the gun, only to be stopped in their tracks with a sharp, ‘Don’t turn round. Face the front.’

They waited and then the cockney voice continued.

‘If you do everything I say and don’t make a noise you will be alright.’

This did not bode well. ‘If you do everything I say’ had a worrying undertone. Michael, sensing that the man needed to be reasoned with, said, ‘I’m sorry you haven’t eaten anything. We’ve nothing to offer you but we’re willing to drive you into town to get a meal or something,’2 an attempt on his part to at least move to a busier, safer area. The response was blunt.

‘Don’t be silly, I have gone without before. Just keep quiet and you’ll be alright.’

A short silence.

‘This gun is real,’ he continued.

His uneducated voice, as Valerie would later describe it, now seemed to gather momentum. It was as if he had not really got a plan and was filling in time with pointless chatter.

‘It’s like a cowboy gun. I feel rather like a cowboy.’

He said it was a ‘thirty-eight’, though Valerie had no idea what that meant. It was loaded, he boasted, and tapped his pockets, which let out a rattling noise. ‘These are the bullets.’ He said that he had never shot anyone before and was waving the gun about as if to show it off, so much so that Valerie caught a glimpse of it against the silhouette of the failing light. ‘It was black or dark and had a barrel about six to eight inches long,’ she would later recall.

Each time the couple in the front tried to turn around to catch a better glimpse of their captor, a raised voice would order them to ‘face the front’. Continuing to talk aimlessly, he repeated that he had not eaten and had been sleeping rough for a couple of nights. Valerie reflected on his tidy appearance and thought it odd that a man who had been without food and shelter for a couple of days would be so ‘nattily dressed’. He was not making sense and frankly, she did not believe him.

Repeated requests by Valerie and Michael about what the man wanted were met with poorly thought-through answers. ‘There’s no hurry,’ he responded on several occasions and often he used the phrase, ‘Be quiet, will you. I’m finking.’ His inability to pronounce ‘th’ was a prominent feature in his voice.

Their fears escalated when he suddenly exclaimed that if anyone walked past, he would shoot them. Almost as if boasting, Valerie thought, the man outlined how he had been to prison and ever since he was 8 years old he had been in remand homes, borstal, CT – an abbreviation that was meaningless to Valerie – and his next one coming up was PD, an equally meaningless abbreviation. He had also been to prison for five years for housebreaking, he said.3

The conversation continued with the gunman repeating phrases, yet often contradicting himself, Valerie and Michael both making desperate attempts at trying to establish what it was that he wanted. The longer it went on, the more they tried to reason with him. But now their terror heightened. They had been held captive for probably no more than five minutes, when the man wielding the gun handed the ignition key back to Michael and told him to drive further into the field. No lights, he instructed, just drive further in. This was it. He had clearly decided what he wanted to do.

Michael started the car and drove towards some haystacks, following the instructions of the man in the back seat, carried out a three-point-turn, and with the Morris now facing the entrance to the field, switched off the ignition and returned the key. The man’s motive now became clear. He demanded Michael’s wallet. Valerie, seemingly still able to think rationally under the extreme circumstances, urged the gunman not to take it as it was of sentimental value. The request was tempered with a promise that he would return it and Michael passed it back. It contained around £3. The next was for their watches, which they slipped from their wrists and passed backwards, looking forward all the time. Next came the demand for Valerie’s purse, in her shopping basket, which she knew only held a few coins and she told him that in the hope it might make him change his mind. Moreover, she was concerned that she had a wallet in her basket that contained several pound notes and she was determined that he was not going to get his hands on it; she and Michael needed it for their future.

Her ploy worked but he now wanted her handbag. She had an idea. She asked whether she could keep her cosmetic bag, to which the man giving the instructions made a jocular response about women always needing their makeup. He agreed and Valerie removed her cosmetics, but also managed to retrieve her fountain pen, and she slipped them both into the glove compartment. The light had now practically disappeared, and in the darkness Valerie picked out her wallet from her basket, opened it and removed the pound notes. She grabbed her handbag out of the basket and passed it to the back, and slowly, without any sudden movement, secreted the notes inside her bra. There was no challenge from the back and she was relieved that her quick thinking had gone unnoticed. At least her money was safe and perhaps now that the man had got what he had come for, the ordeal would soon finish. He would just walk off or perhaps more annoyingly, make them get out of the car, and steal it. That would hurt, stealing their Morris.

But the pointless conversation continued.

He knew Maidenhead, he said, a town a few miles along the M4, said he had been to Oxford and repeated that he was a wanted man. But now he remembered he was hungry. Had they got anything in the car he could eat? They had not, but it gave Michael and Valerie an opportunity to suggest an escape. They told the gunman to take the car so that he could go and get some food. The suggestion was refused. They offered to drive him somewhere where they could buy some chocolate and then return to the field. This was also declined and it was now met with the idea that he would wait until the morning, tie them up and then go. There was no hurry.

Between them they urged the man to leave there and then, while it was dark. That way he would not be seen. He did not like that idea either. What did this man want? He had got their money – well, some of it at least – so why did he not just simply take up their offers of escape? The frustration continued. He now asked them whether they were married and they explained that they were not. He asked their names and they told him and in quick retort, Valerie asked for his. Unsurprisingly, he refused. They offered once more for the man to take the car but the same answer came from the back: ‘There’s no hurry.’

It was now about half past ten, almost an hour since the tap on the window and the weapon poked through. They had been held at gunpoint, robbed and had offered the man the opportunity to disappear into the night, but he seemed to be dithering. Suddenly, a light emerged from one of the nearby houses. A man came out and it looked as though he was putting away a bicycle in a shed. The gunman reacted: ‘If that man comes over here, don’t say anyfing. I will shoot him and then I’ll shoot you.’

Valerie assured him that the man would not be able to see the car in the dark and there was nothing for him to worry about. The threat though was repeated. If he came anywhere near the car, people would die.

The man who emerged from the house had not seen the Morris. He simply put his bicycle away and went back inside, unaware of the drama unfolding a hundred yards away. The danger had passed but the tension inside the Morris was palpable. The man had now threatened to use the gun. Another hour of aimless conversation followed. It was in Valerie’s words, ‘a game of cat and mouse with the gunman’. It was as if he had got himself into a situation he had never envisaged and now couldn’t work out how to get himself out of it.

It was another forty-five minutes before things changed. ‘I can’t stand it any longer,’ the man in the back said. He was hungry and wanted to find something to eat. Pointing the gun directly at Michael, he told him to get out. He unlocked his door and stepped into the field, the gunman climbing out at the same time. Michael was told that he was going to be put in the boot of the car and he was instructed to open it.

What followed was another act of defiance from Valerie. She had already tried to prevent her boyfriend from handing over the ignition key, had secreted money in her bra and now she instantly took action realising what was just about to happen. Knowing that Michael would be trapped inside the boot, she prepared his escape. With the gunman preoccupied with Michael, she reached over and grabbed hold of the tags on the back seat. She tugged hard and pulled the seat away from the boot frame. Michael would now be free to clamber out if the opportunity arose. She had acted just in time. The gunman, who she could now see had a grey or white handkerchief across the bottom half of his face, gangster style as she described it,4 leaned in, and grabbed the rug from the back seat saying he was going to put it in the boot. It was clear what was happening and both Michael and Valerie now made a false claim. The car had a leaking exhaust, they said, and if the car was driven with Michael in the boot, he would suffocate from the fumes. Incredibly, this had an effect on the man giving the instructions. He thought about it and changed his mind. The boot was closed and Michael was instructed to get back into the driver’s seat.

The stress was starting to get to Michael. He had almost been bundled into the boot and had escaped merely by the exaggeration about the exhaust pipe. Had the threat been carried out, what would have happened to Valerie? Although trying to cut down, he was a heavy smoker and now needed something to settle his nerves.

‘Do you mind if I have a cigarette?’

‘No,’ came the reply, and he pulled a packet of cigarettes from his pocket. There was only one left.

‘Do you smoke? I’m sorry, I only have one left.’

‘No, I don’t like smoking.’

Michael lit the cigarette and drew heavily on it. He smoked quickly, and when he was halfway through, Valerie’s level-headedness again came to the surface.

‘Why not put it out and save the other half for later? You’ll probably need it.’

Michael stubbed it out.

Valerie was analysing all the information she had taken in. The gunman, she thought, was probably local to the area owing to their relatively isolated location, and it would have been impossible for him to have known that they were going to be parked there that evening; it had been a last-minute decision. He was clearly ill-prepared, not knowing what he wanted to do and kept contradicting himself time and time again about locations he had visited and detail about his background. He was obviously a thief, but why this? Brandishing a gun made no sense. He was, she surmised, just a poorly educated, young cockney criminal who was enjoying being a cowboy for the evening. Despite this, she was petrified and her anxiety levels were just about to increase.

He told them that they were going to drive but he was going to do the driving. On the face of it, this did not make any sense. If the gunman was driving, he would presumably have made at least one of them get into the back seat, which would have made him vulnerable to being grappled with from behind. Despite this being an opportunity for them both, the couple talked him out of it, particularly, as Michael said, he knew how to drive the car. This comment would play an important part when later analysing the events that were about to begin.

The gunman seemed to agree with their sentiment and the ignition key was passed from behind. The self-styled cowboy was hungry and they were going to get some food, he told them. This was frightening. No longer would an escape from the cornfield be possible. They had been held captive for two hours and the Morris Minor, now with its lights on, edged slowly towards the entrance of the field and turned left onto Marsh Lane.

Chapter Three

On to the A6

The front-seat occupants of the Morris were now experiencing a cocktail of emotions; concerned for their lives but maintaining a small hope that the ordeal would somehow soon be over. What the gunman had done so far was serious enough and if he was ever caught, he would undoubtedly go to prison. It was a little ironic that only a few weeks earlier the government had announced a three-month amnesty on firearms in the hope that many would surrender unwanted weapons, many of which had hung around in people’s drawers and cupboards since the end of the Second World War. The police had expressed deep concern about just how easy it was to get a gun and in the hands of criminals it would make the country a dangerous place. In fact, in the first week of the amnesty, more than 1,300 weapons had been handed in at police stations, which rather proved their point.1

Such a criminal and such a gun now appeared to be in the back of the car and the position was dire. Perhaps, though, the gunman had had his fun already and he would just simply slip away without any hint of who he was. Perhaps even, he would merely want dropping closer to his home. He would tell them to keep facing the front, clamber out and they would drive off. They would not be able to identify him. And if he made off with the ignition key to give him time to escape, Valerie had deftly slipped a spare one from the glove compartment into her make-up bag. She was thinking ahead.

Immediately after leaving the cornfield, the car crossed over the recently opened M4 motorway, prompting the gunman to demonstrate that he had not yet grasped the concept of how this new type of road worked. Asked whether they could get on the motorway there and then, the couple in the front explained to him that in order to join you needed to get to a particular junction for that to happen. Instead, they crossed over the bridge and met with the A4. A discussion took place between the three of them about which way to turn, the gunman giving out confusing messages about where he wanted to go. To the left were Maidenhead and Bath; he had had enough of Maidenhead, he said. To the right was London; he didn’t want to go there either. Michael and Valerie asked again. There was no hurry, he retorted. He was ‘finking’. Finally, he decided on Northolt, to the right, and they headed off.

Given that the man had said he was hungry, Valerie again suggested they look for a chocolate or milk vending machine so that he could get something to eat or drink and, passing through Slough, they pulled over at Nevill and Griffins dairy. They stopped next to a milk machine, which needed sixpences. No one had any, which gave Valerie the idea about another possible escape.

‘Shall we try and stop someone to ask?’ she suggested.

‘No, don’t do that.’

He knew a café in Northolt where he could get food. They were ordered to drive on.

Occasionally, when speaking to Valerie, the gunman referred to Michael as her husband and more than once she told him that they were not married. He did not seem to be able to grasp the fact. He asked where they both lived, and they told him. The conversation reinforced Valerie’s view that this was a man in his twenties and had no idea what he wanted. He changed his mind several times over whether they were to return to the cornfield in Dorney once he had eaten but the mention of Northolt seemed to confirm that they were on a journey that would take them well away from the spot where they had been caught by surprise.

As they drove through Slough, the time on the post office clock showed 11.45 p.m. They had been in the car under threat of death now for over two hours and it would have struck Valerie that as they passed through the town, she was within a couple of hundred yards of her home where her parents would probably by now have been worried about their daughter’s late arrival home. ‘Shan’t be long,’ she had shouted back as she had left and now, four hours later, she was going in the wrong direction heading for Northolt and an opportunity at the milk machine to escape had been and gone. Being close to home, Valerie made a desperate pitch, suggesting to the gunman that he should just abandon them and take the car. It was not to be. The order to continue driving remained.

There were times when silence filled the car. Little was said as they drove in the general direction of London. Valerie and Michael exchanged glances, well aware that a gun was pointing directly at them.

The silence was broken.

‘How much petrol has the car got?’ the voice from behind said.

One gallon, he was told, and it would only go for another 20 miles, a desperate attempt by the two of them to encourage the gunman to make a decision quickly about what he wanted to do. In fact, it had 2 gallons in its tank. His response was not encouraging.

‘We’d better get some petrol.’

Obviously planning on travelling a long distance, he wanted the car filled with 4 gallons of fuel. Afraid that a full tank would increase the prospect of them being held captive in the car for a long time, Michael lied and said that the car’s fuel tank was not big enough to hold that amount. The man thought for a second and then said:

I want you to go in and get 2 gallons of petrol. You’ll stay in the car, wind down the window and ask the man for 2 gallons only. I have the gun pointing at you and if you try and say anyfing else or give the man a note or make any indication that anyfing is wrong, I’ll shoot.

The Morris pulled over into a Regent petrol station just beyond the Colnbook bypass close to London airport and the gunman handed Michael one of the pound notes he had earlier stolen from his wallet.2 If there could ever be a lighter moment in this terrifying situation, Valerie would later say that Michael was really fussy about which type of petrol he put in his car and would have hated having to put Regent fuel into his beloved machine.

In reality, Valerie was now absolutely petrified. This was a time well before automated fuel pumps dominated garage forecourts. Motorists requiring fuel needed to pull alongside a petrol pump and wait until the garage attendant approached them. The driver would then tell the attendant how much fuel to put into the tank and once completed, pay the garage employee, waiting, if necessary, for any change that was due.

Much later, Valerie reflected on how a man, masked with a handkerchief across his face and brandishing a gun, could get away with pulling on to a garage forecourt and being seen in the rear seat dressed so inappropriately. She could never be sure, since she was being permanently reminded to face the front, but she sensed that he must have been removing the handkerchief at certain times to ensure he did not attract unnecessary attention. It would have been easy for him to simply lower the gun away from any prying eyes outside yet keep it aimed at its potential victims.

All Michael had to do, though, was put one foot wrong, a minor deviation from the plan that unnerved the cowboy, and she would be shot dead. But, with the gun pointing directly at her head, Michael did exactly as he was instructed, told the garage attendant he wanted 2 gallons, handed him the £1 note and received 10s 3d in change,3 which the man in the back immediately demanded. In another act of misplaced humour, the gunman handed the threepenny piece to Valerie and said, ‘You can have that as a wedding present.’

The instruction was given to drive off. Once again, an opportunity to escape had passed them by. Had one of them tried to alert the garage attendant or even simply tried to run from the vehicle, it could have ended in disaster. But with the car now containing around 4 gallons of fuel, the Morris drove from the garage forecourt capable of driving over 150 miles.

The instructions now came thick and fast. ‘Turn left here. Now turn right.’ Hesitation, and then more instructions. It was apparent that there was no clear plan but, given his directions, it seemed clear that he did not want to go in the general direction of central London. Trying to take advantage of the situation, both Valerie and Michael gave their kidnapper numerous opportunities to just take the car and abandon them, but each time their offer was refused. There was no hurry. He was ‘finking’.

There was more conversation about food and the need to get to Northolt as they made their way through the Middlesex suburbs of Hayes and Stanmore, just outside north-west London. Michael was stressed and told the man that he needed some cigarettes and for a moment, the voice in the back became distracted. As they passed a cigarette vending machine he gave Michael the opportunity to buy some.

‘You can stop and get some there. You can get out but don’t do anyfing silly because I am pointing the gun at the girl.’

They pulled over, and before he stepped out, Michael kissed Valerie on the cheek and told her not do anything silly while he was away.4 He went to the machine, bought a packet and returned to the vehicle. Again, neither took the opportunity to attempt an escape. The risks were too high. Michael climbed back into the driver’s seat and offered a cigarette to the man.

‘Do you want one?’

‘Yes,’ came the reply, despite him earlier saying that he did not smoke. ‘But go on driving.’

Valerie took the packet from Michael, removed two cigarettes and placed them in her mouth. She lit both and handed one to Michael, the other to the gunman. As he took it from her, she saw for the first time that he was wearing a pair of black gloves. She couldn’t tell whether he actually smoked the cigarette as he continued to call out his indiscriminate directions.

He told Michael to be careful, somewhere near Stanmore, Valerie thought, as he said there were some roadworks around the corner. He was right, there were; he clearly knew the area. Probably realising he had given away a piece of information about himself, he quickly tried to claw the situation back.

‘I suppose you think I know this area but I don’t,’ he said.

More nervous commands followed. ‘Mind that crossing,’ he once said. ‘Be careful of those traffic lights’ and ‘mind this corner’.

Desperate to make sure no harm came to them, Valerie tried to develop some form of human connection with the man wielding the gun by engaging him in conversation. His apparent nervousness provided an opportunity.

‘Can you drive?’ Valerie asked.

‘Oh yes. All sorts of cars.’

The conversation continued about vehicles and at one point he asked Michael to explain the position of the gears on the gear lever, perhaps an indication that he planned on later stealing the car but also that maybe he was unfamiliar with this type of vehicle. A striking feature about the man’s knowledge of cars arose when Michael needed to change down to third gear, at which point the gunman asked why he hadn’t selected first. ‘He certainly didn’t know much about cars, certainly very little about Morris Minors,’5 Valerie would later say.

They never did stop for food or drink. Instead, they drove aimlessly through Middlesex, never actually getting to Northolt due to them taking a wrong turn, and eventually driving into southern Hertfordshire. Valerie specifically recalled just missing Watford, going through Aldenham and then Park Street, a terminal entrance for the M1 motorway.6 Approaching a roundabout, Michael asked for directions.

‘Which way do you want to go?’

‘St Albans.’

From this point on, the road turned into the A5, reinforcing the point that they were on a long journey, now nearly 40 miles away from home.

With the car travelling along at speeds between 30 and 50mph, the engine noise provided the opportunity for Valerie and Michael to communicate with each other through eye movements and by whispering in undertones. Valerie would later say that, ‘He didn’t seem to bother what we were saying, just as long as we faced the front and didn’t turn our heads. He didn’t seem to worry.’7 The man was preoccupied, she felt, most likely considering his next move.

They too were scheming and their whispered plan of an attempt to escape or at least to frustrate the gunman was remarkable.

‘We had a plan,’ Valerie later told a jury. ‘If we saw a policeman, Michael would pretend to have a steering problem with the car and pull up on the pavement next to him. I was going to hit him [the gunman] with a screwdriver I had armed myself with. However, when you want a policeman there is never one available and we didn’t see one on our journey.’

She would later allegedly tell a journalist that she had also armed herself with a box of matches and she was considering lighting some of them and throwing them into the gunman’s face, but this never featured in the accounts she would later tell the police. Quite how the ‘policeman’ plan was discussed without the gunman being alerted is remarkable. But, with no policeman in sight they continued their journey north.

They persisted with more ideas. Valerie suggested to Michael that when driving in built-up areas, they should slow down in an attempt to draw attention to themselves but when in the de-restricted areas, they should speed up. This was going well until the order came from the back to not go over 50mph.

Desperation had kicked in and they put the next part of their whispered conversation into place. The Morris was fitted with a reversing light, which was operated by a single switch underneath the dashboard to the left of the driver and which could be switched on and off without anyone in the back seat realising. As they idled along, Michael started to repeatedly switch it on and off in an attempt to alert someone – anyone. He flashed his headlamps at motor cars as they came towards him, switching between main and dipped beam. It had no effect, though quite what he hoped to achieve is not clear.

The Morris Minor rumbled along, Michael still making attempts to speed up in the quieter areas, before they eventually approached St Albans.

‘Go to St Albans,’ came the direction.

‘This is St Albans.’

‘No it isn’t. This is Watford.’

Watford was about 8 miles south of where they were but the gunman would not accept the point. It was clear that he did not know where he was, what he wanted or where he was going. The couple chose not to argue and they drove on. Approaching yet another roundabout, they asked for further directions.

‘Straight on.’

They were now on the A6, north of Luton, 50 miles from the Dorney cornfield and Michael continued to flash his reversing light.

Half a mile behind them, driving to work, Rex Mead and his passenger were distracted by the vehicle in front of them, a rear white light flashing on and off. Mead estimated that the time was around 12.20 a.m. He travelled behind it for a while, for about 500 yards, he thought, and decided that ‘it was doing nothing silly,’ and ‘only doing about 25–30 miles per hour,’ so he opted to overtake. As he passed slowly by, he looked to his left and saw three people inside. Two were in the front and the other was in the rear, offside seat. Mead’s passenger gestured to them in an effort to establish if everything was alright but none of them seemed to notice him. With everything apparently in order, Mead accelerated past them.

His observation of the threesome in the Morris tends to support Valerie’s later thoughts that the man in the back would occasionally remove his mask to avoid people staring at him. It would have been a simple enough task.

Mead did not know that inside the car he had spotted with the flashing reversing light, tensions were high. This had been the opportunity both Valerie and Michael had been waiting for, yet they did not react. They did not start to drive in an erratic manner to grab Mead’s attention. They did not sound the car’s horn. They did not wave frantically to make it obvious that there was a gun pointing at the back of their heads. They simply carried on driving, hoping that somehow the overtaking driver, in his 1956 Hillman or 1954 Ford Anglia, Valerie thought, would instantly recognise the dangerous situation they were in and do something about it. But, of course, he did not. He could not have known. They had devised a plan, put it into action, and then did nothing.

The man in the back, though, was nervous.

‘What did they want?’ he demanded. ‘They must know something is wrong.’

In an effort to defuse the tension and scared that he would overreact and shoot them, they made a suggestion.

‘One of the stop lights might have gone out. One of the bulbs is loose, isn’t it Mike?’ Valerie quickly, misleadingly, suggested.

They were instructed to stop. Michael switched off the reversing light, was ordered to surrender the ignition key and the man stepped out and edged towards the back keeping his hand on the rear door.8

He got back in and said, ‘They are OK [the lights]. You must have done something.’

The ignition key was handed back and Michael was ordered to carry on with the journey, but it was clear that the gunman had become unnerved.

This had probably been their only real opportunity for them to have driven off and left the gunman on an unlit stretch of the A6. But it was over in an instant. He was out of the car for only a few seconds and did not give the couple in the front the time to grab the spare key, put it into the ignition and drive off. The kidnapper would have easily had the time to jump back in and take whatever revenge he thought necessary. Limited though it was, this window of opportunity had now gone and once again they were heading north, now almost 60 miles from home.

The subject of food had long since disappeared from the conversation. Perhaps the shock of the overtaking car had had some effect on the gunman. He had held Michael and Valerie captive for over three hours and been giving constant directions, albeit without any measure of confidence. At one point he handed back the watches he had stolen from them, perhaps the first hint that the man’s motive for this treacherous journey was not to steal. Valerie slid both of them onto her left wrist and told Michael that she ‘will put yours on my wrist, darling’.9 She could detect that the man in the back kept on looking at his own watch, before saying that it would soon be daybreak, told them again that there was no hurry and that he was ‘finking’. It had become monotonous. But suddenly the instructions changed. He needed to sleep, or to use his exact phrase, he wanted ‘a kip’.

With her skills in map reading and navigation, Valerie distinctly remembered driving through the villages of Barton-le-Clay and Silsoe, Michael still earnestly flashing his reversing light, as the gunman looked for somewhere that they could stop. Ronald Chiodo, an American airman who had just finished work, remembered driving south on the A6, between 1.30 and 1.45 he recalled, when he saw in his reversing mirror the flashing light on the back of a car travelling in the opposite direction. He thought it strange but carried on.

Suddenly, the gunman shouted out.