18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

John Lee is the most infamous Victorian criminal after Jack the Ripper. Found guilty of the murder of his employer, he was sent for execution but three times the trap failed to open. Released from gaol after 23 years, he married, then abandoned his family and disappeared. This text pieces together his story, reviewing and presenting new evidence.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Ähnliche

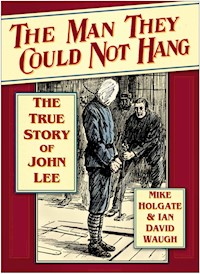

The Man They Could Not Hang

The Man They Could Not Hang

The True Story of John Lee

Mike Holgate & Ian David Waugh

First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Mike Holgate and Ian David Waugh, 2005, 2013

The right of Mike Holgate and Ian David Waugh to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9531 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

To the memory of Torbay’s ‘Mr History’, John Pike (1921–2004)

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgements

Prologue

1. The lure of the sea

John Lee starts work for Emma Keyse at The Glen. Emma Keyse and her connections with the royal family. Lee joins the Royal Navy. Discharged following a bout of pneumonia.

2. Troubles and misfortunes

Employment at Kingswear hotel, GWR; footman at Ridgehill. Arrested for theft in Plymouth. Sentenced to six months’ hard labour. Accepts offer to rebuild his character at The Glen. Becomes engaged to dressmaker Kate Farmer. Sale of The Glen: Miss Keyse murdered and Lee arrested.

3. News of the Babbacombe tragedy

How the murder was reported in regional, national and international press. Funeral of Miss Keyse.

4. Committed for trial

Extraordinary inquest into the death of Miss Keyse at St Marychurch Town Hall. Magistrate’s hearing at Torquay Police Court. John Lee committed for trial.

5. A foregone conclusion

Devon County Assizes. Trial of John Lee at Exeter Castle.

6. On the brink of eternity

Letters from the condemned cell. Appeal for clemency on grounds of insanity. Execution of John Lee abandoned after unsuccessful attempts to hang him.

7. Imprisonment for life?

John Lee’s life in prison and campaign for freedom. Release in December 1907. Negotiations for his ‘life story’.

8. Lady killer

Choosing a wife after considering numerous offers. Abandoning his wife and children in 1911. Voyage to New York.

9. More lives than a cat

Death of John Lee in Australia 1918, Canada 1921, USA 1929 or 1933? Surviving London Blitz? Death in Tavistock Workhouse 1941? What made Milwaukee infamous?

10. The bungle on the scaffold

Providence, witchcraft, incompetence, rain, sabotage. Home Office report on the failure of the scaffold.

11. If it wasn’t the butler – whodunit?

Who’s Who of suspects: the nobleman, fisherman, builder, smuggler, woodcutter, silver dealer, lover.

12. Whispers from the law chambers

The secrets of South Devon solicitors Percival Almy, Isadore Carter, Ernest Hutchings and the deranged Reginald Gwynne Templer.

13. John Lee – a victim of circumstance?

Lee’s conviction on circumstantial evidence. An examination of the case conducted by the prosecution and defence. Possible motives for the murder of Emma Keyse.

Sources

Select Bibliography

Preface and Acknowledgements

Mike Holgate’s interest in the case of John Lee was stimulated by the BBC2 television documentary The Man They Could Not Hang, presented by Melvyn Bragg and broadcast on 1 February 1975. Mike was then living in Torquay near the scene of the Babbacombe Murder. The programme featured music performed by Fairport Convention from their folk-rock album ‘Babbacombe’ Lee. A year later, singer-guitarist Mike supported the band in concert on a tour of the West Country. At this time his father was carrying out some family history research after hearing from a relative that a branch of the Holgate family named Lee might be descended from the infamous criminal. This myth was quickly dispelled after receiving assistance from Torquay Borough Librarian John Pike, who had acted as a researcher and appeared in the BBC programme.

In 1990, Mike joined the staff of Torquay Library as a part-time reference library assistant; the aim was to supplement his income as a musician and further his knowledge in order to fulfil a vague ambition to become a local history writer. In this new post he regularly carried out searches on behalf of would-be authors planning to write a book about John Lee, none of which was ever written. When he realised that no one had devoted a full volume to the subject since John Lee’s autobiography was first published in 1908, he decided to write one himself. This was made possible by the encouragement and cooperation of John Pike, by this time retired from the Library Service and established as an eminent author on local history. He generously handed over the results of his research started in 1959, which Mike bolstered with evidence from recently declassified archives obtained from the Public Record Office. The result was The Secret of the Babbacombe Murder, published in South Devon by Peninsula Press in 1995, which later that year formed the basis for an episode of Granada Television’s crime series In Suspicious Circumstances presented by the actor Edward Woodward.

Reading the book rekindled the interest of broadcast producer and presenter Ian Waugh, who had been told tales of John Lee by his grandfather. In 1999, he visited Torquay Library and obtained advice from Mike Holgate. His first objective was to transcribe the witness statements of the magistrate’s hearing from the Torquay Court Records held at the Public Record Office. When this was achieved he produced a booklet entitled Who Killed Emma Keyse? Ian then turned his attention to the daunting task of transcribing hundreds of handwritten Home Office and Prison Commission documents relating to the case and launched a comprehensive website about John Lee. This was visited by a recently retired policeman, Don Hanson, who contacted Ian and passed on an invaluable file of John Lee’s correspondence with his supporter Stephen Bryan, which had been deposited at the Exeter Prison Museum. Together with a tantalisingly plausible tale of Lee’s last resting place, obtained by following up a story told to Exeter publisher Chips Barber, which ironically led back to the town of Tavistock where Ian had been raised, there was now enough material to team up with Mike and produce a book.

Mike and Ian have collaborated and researched, with varying degrees of success, three intriguing aspects of the life of John Lee: How did he escape the death penalty? What became of him after serving life imprisonment? Was he guilty of the Babbacombe Murder? They do not claim to have found all the answers, although their research belies much of the folklore and press coverage surrounding this fascinating subject. They have strived to produce a comprehensive overview of the case, extensively quoting official documents, contemporary newspaper reports, expert opinion, titbits of local gossip and the letters and personal accounts of the principal characters involved.

Before approaching a publisher, Ian and Mike sought advice from a mutual acquaintance, Stewart Evans, renowned author of Jack the Ripper, then finalising The Chronicles of James Berry – a biography of the executioner who failed in his duty to hang John Lee. Stewart kindly recommended the authors to Sutton Publishing Ltd, whose editor, Christopher Feeney, immediately commissioned the work.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of those people already mentioned and are indebted to the following individuals and organisations for providing various segments of a story whose telling can be likened to piecing together a giant jigsaw puzzle. If anyone reading this book can provide any of the missing pieces of information, then Ian and Mike would certainly be glad to hear from them. Look us up at www. murderresearch.com.

Library services

This project would not have started without access to the local history archive at Torquay Central Library. Many past and present members of the reference staff have contributed invaluable help and assistance, and grateful thanks are due to Mike Dowdell, Ann Howard, Lorna Smith, Lesley Byers and Mark Pool for their ongoing advice and encouragement. Many thanks also to library users Ray Strevett, Don Collinson, Terry Leaman and Mike Wells for interrupting their own research to turn up vital snippets of information.

Many other libraries have been contacted at home and abroad in our quest, and the authors would like to express their appreciation to staff members of the following institutions:

England: London: Guildhall, Marylebone, Southwark, City of Westminster Archives; Bradford; Exeter (West Country Studies Library); Gloucester; Leigh; Manchester; Newcastle-upon-Tyne; Newton Abbot; Plymouth; Redruth;

USA: Brooklyn; Buffalo; Chicago; Milwaukee; New York; University of Wisconsin; Illinois State Library;

Canada: Toronto;

Australia: State Library of New South Wales; State Library of Victoria.

Records and documents

Grateful thanks to Dr Stephen Smith for conducting the time-consuming search for the Torquay Court Records at The National Archive, Kew. A special mention is also due to the staff of that establishment for locating and supplying copies of Admiralty, Assize, Home Office and Prison Commission records relating to John Lee. Appreciation to Ian Mulholland, Governor of Exeter Prison, for permission to quote the correspondence of John Lee, Stephen Bryan, Mrs Caunter, Fred Farmer and George Bond. With thanks to the Galleries of Justice, Nottingham, an educational organisation educating the wider community about crime, punishment and the law – and its librarian/archivist Bev Baker for permission to quote from documents in the Epton Collection. Special thanks to K.M.J. Caine of the Devon Record Office, for information relating to the workhouse records of the Tavistock Institution; Pamela Clarke, Deputy Registrar, for information from the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle: Douglas Parkhouse, Cemetery Superintendent, Tavistock, for undertaking the search of burial records, Derek Reed, solicitor, Woollcoombe, Beer & Watts, Newton Abbot, for providing a copy of the will of Mary Lee; Steve Daily, Curator of Research Collections, Milwaukee Historical Society, for a search of naturalisation records; the State of Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services for locating vital records relating to the Lee family; Bob Gartz for information regarding the records and graves of the Lee family in Milwaukee; Alan Elliott for locating the family records of Elizabeth Harris in Australia.

Miscellaneous

Appreciation to the following organisations, which provided assistance in a variety of ways: BBC South West, British Film Institute, Devon Family History Society, Lincoln County Council, London Metropolitan Archives, National Film and Television Archive, Plymouth District Land Registry, Probate Registry, Salvation Army, Surrey County Council, Tavistock Town Council, Teignbridge District Council, Torbay Council, Torquay Museum, Television South West (TSW) Film and Television Archive, Wellcome Trust. Also, special thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to the project: the late Leslie Lownds Pateman CBE, Gordon Honeycombe, Susan Arn, Edna White, Wendy Harvey and Sandra and Shirley Harris. Kind assistance was also received from the late Frank Keyse (a descendant of the murder victim’s family) and his widow, Margaret.

Newspapers, journals and books

For dealing with our frequent and persistent enquiries for copies of contemporary newspaper reports we thankfully acknowledge the diligent cooperation of staff members at the British Newspaper Library, Colindale. For permission to quote extracts from newspapers, journals and books, grateful thanks are extended to the representatives of the following copyright holders: Duncan Currall, MD of Westcountry Publications (Herald Express, Express and Echo, Western Morning News); Mike Roberts, MD of Torquay News Ltd (Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser); Colin Brent, editor of the Tavistock Times and Gazette; Paul Robertson, editor of the Newcastle Evening Chronicle; Jenny Potter, managing editor of the Radio Times; Kate White of Guinness Publishing Ltd. Last, but not least, we would like to thank our ‘partner in crime’, barrister Barry Phillips, contributor to the law journal Counsel, and its editor, Stephanie Hawthorne.

Illustrations

Supplementing photographs and illustrations from the authors’ own collection is The View from my Bedroom Window, painted by Emma Keyse in 1876, photographed by Shane Edgar and reproduced courtesy of Torre Abbey Historic House and Gallery, Torquay. Special thanks to David Mason of Torbay Postcard Club for providing postcards of St Marychurch Parish Church and ‘John Lee’s Mother’. A portrait of P.S. Abraham Nott, photographs of The Glen and South Devon business advertisements have been provided courtesy of Torbay Library Services. Thanks also to John Draisay, County Archivist, Devon Record Office, for providing a Crown Copyright copy of the cheque obtained for stolen goods by John Lee (QS4/Midsummer 1883). The majority of the line drawings illustrating the text were originally published in contemporary editions of the Devon County Standard, Illustrated London News, Torquay Directory and South Devon Journal, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, provided by Torbay Library Services, and the Illustrated Police News, Sunday Chronicle, The Builder, obtained from the British Newspaper Library. Further sketches from an extra supplement to the Devon County Standard and a souvenir Record of the Dates of the Visits to Babbacombe by Members of the Royal Family have been copied from originals held at Torquay Museum. Paul Williams provided illustrations from the Edwardian magazine Famous Crimes. Ian Waugh re-created plans of The Glen and the map of the ‘Babbacombe Murder Trail’. Timothy Lau adapted technical drawings of the scaffold from an original held at The National Archives (HO 144/ 148//A38492).

Prologue

On a damp overcast morning in February 1885, an expectant hush fell over the large crowd gathered outside Exeter Prison. At 8 a.m. the prison bell tolled the death knell for John Lee, a twenty-year-old servant sentenced to death for a crime rightfully described by the trial judge as ‘one of the most cruel and barbarous murders ever committed’.

The apparently motiveless murder of elderly Emma Keyse at her seaside villa The Glen at Babbacombe, Torquay, had shocked the sensibilities of everybody in the locality. The elderly victim had been callously bludgeoned to death with blows to the head before her throat was slashed and her lifeless body set on fire. Any moment now the black flag would be hoisted above the prison to signal that the evil perpetrator had paid the full penalty of the law for killing a lady he himself described as ‘my best friend’. She had taken him into her service and shown a kindly interest in his welfare, despite the fact that he had served six months’ hard labour in this very prison for stealing from his previous employer.

The View from my Bedroom Window – painted by Emma Keyse.

The crowd grew uneasy as the minutes passed by without the expected pronouncement. Perhaps the miserable wretch had finally abandoned his stubborn protestations of innocence and admitted his guilt, delaying the proceedings with a protracted confession? Half an hour later there was still no news. Surely the condemned man had been granted a last-minute reprieve? Perhaps there was some truth in the written statement made earlier by the prisoner in his death cell, implicating the lover of his half-sister, Elizabeth Harris, who was expecting an illegitimate child conceived while she was the cook at The Glen.

Speculation continued for a further twenty minutes, until members of the press suddenly emerged from the prison gate and rushed towards the telegraph office. They were immediately engulfed by people clamouring for information. A besieged reporter breathlessly revealed:

‘It’s a bungle!’

‘What?’

‘Can’t hang the man!’

‘What do you mean?’

‘They’ve tried three times and he’s still not dead!’

Inside the prison, shocked officials, whose onerous responsibility it was to carry out the death sentence, were reliving the full horror of what had occurred. It was their painful duty to witness the execution – and more than one had fortified himself with a drop of Dutch courage, although nothing could have prepared them for the harrowing scenes that were to follow. They had assembled anxiously at the appointed hour as the prisoner mounted the scaffold, stood calm and erect, then glanced skywards for a moment before the executioner, James Berry, made the necessary preparations for his grim task. He quickly pinioned the condemned man’s legs, drew a white cap over his head, then tightened the noose around his neck: ‘Have you anything to say?’ he whispered.

‘No,’ came the firm reply. ‘Drop away!’

The hangman hesitated while the prison chaplain read a somewhat prophetic passage from the service from the Burial of the Dead: ‘Now is the Christ risen from the dead . . .’.

At the appropriate moment, Berry pulled a lever to activate the ‘drop’, then gasped in amazement as the trapdoors merely sagged slightly, leaving the prisoner precariously suspended between life and death! ‘Quick, stamp on it!’ he shouted to the warders.

Distressing scenes followed as desperate efforts were made to force the ‘trap’ open. Warders jumped on the doors, risking falling into the pit with the prisoner had they been successful, but after several minutes the bewildered prisoner was led to one side while the apparatus was repeatedly tested and found to be working perfectly. Visibly shaken, Berry made a second attempt. Heaving with all his might, he succeeded only in bending the lever, then abandoned his post to add his weight to that of the prisoner standing helplessly on the trap – all to no avail!

‘This is terrible,’ cried the anguished Governor. ‘Take the prisoner away!’

Carpenters were summoned to diagnose the problem and a saw was passed around the frame of the trapdoors to relieve possible pressure, in case they were swollen from the overnight rain. As a final test, a warder balanced on the ‘trap’ while clinging onto the hangman’s rope and the doors fell away easily. Satisfied that the fault had now been remedied, the Governor recalled the prisoner to face his ordeal for a third time. The witnesses were in a great state of shock, and the Chaplain trembled as he read more in hope than expectation: ‘Man that is born of woman hath but a short time to live . . .’.

The Man They Could Not Hang.

Perspiring freely, Berry grasped the lever with both hands, determined that this time John Lee would keep his appointment in Hell. The bolt was drawn and the scaffold shuddered.

‘Is it all over?’ pleaded the Chaplain, who was too afraid to look.

‘In God’s name, put a stop to this!’ demanded Mr Caird, the surgeon. ‘You may experiment as much as you like on a sack of flour, but you shall not experiment on this man any longer.’

The Reverend Pitkin opened his eyes and almost collapsed when he realised that Lee had survived a third attempt on his life. He immediately informed the Under-Sheriff, Henry James, ‘I cannot carry on!’

Following a huddled conference, it was agreed to postpone the proceedings pending instructions from the Home Secretary. John Lee was returned to his cell, seemingly unaffected by his torment, but he reacted angrily when Berry came in to remove his bonds. ‘Don’t do that,’ he protested. ‘I want to be hung!’

‘Have no fear,’ reassured the Chaplain, with tears in his eyes. ‘By the laws of England they cannot put you on the scaffold again!’

Lee recovered his composure, then suddenly remembered an extraordinary occurrence which he recounted to the incredulous chaplain: ‘I saw it all in a dream! I was led down to the scaffold and it would not work – after three attempts, they brought me back to my cell!’

The Reverend Pitkin’s assurance to Lee that he was legally protected from having to face the death penalty again was misinformed. However, the Home Secretary, Sir William Harcourt, was empowered to commute the sentence on humanitarian grounds, if he felt it appropriate. Lee’s agonising experience brought about a wave of public sympathy and indignation that was typified by Queen Victoria, who reacted strongly in favour of Lee, even though she had been personally acquainted with the murder victim. She made her feelings known in a telegram to the Home Secretary: ‘I am horrified at the disgraceful scenes at Exeter at Lee’s execution. Surely Lee cannot now be executed. It would be too cruel. Imprisonment for life seems the only alternative.’ Sir William concurred and told a packed House of Commons: ‘It would shock the feelings of everyone if a man had twice to pay the pangs of imminent death.’

Circuit barrister Mr Molesworth St Aubyn, who had conducted the inept defence of Lee, could not disguise his relief in a letter to the Reverend Pitkin: ‘I am one of those who was never satisfied of his guilt. What a marvellous thing if he turns out to be innocent. At any rate he must have a nerve of iron. What will become of him now, I wonder?’

Meanwhile, a thrill of astonishment and disbelief swept through the country as the story caught the public imagination. The sensational morning’s events certainly brought about a remarkable change of opinion. A reviled murderer suddenly became the object of heartfelt sympathy after enduring a terrible ordeal on the scaffold. Reinforced by the startling revelation that the prisoner had prophesied he would not die, a legend was created as John Lee became the only condemned person in the history of capital punishment to survive the ‘long drop’, gaining instant immortality as ‘The Man They Could Not Hang’.

John Lee returns to the world

At eight o’clock on the morning of the 18th of December, 1907, the iron gates of a prison opened, and out into the light of day stepped two middle-aged men.

One man was an official in civilian clothes. He bore the hallmarks of drill and discipline. The other man . . .

The other man! He looked hunted and cowed like a creature crushed and broken. He seemed to hang back as if he were afraid of the light of day. He appeared to draw no happy inspiration from God’s sunshine. He fumbled at his overcoat pockets as if the very possession of a pocket was a new sensation. He trod gingerly, as if the earth concealed a pitfall.

Away they went by cab and rail to Newton Abbot. There the two men walked to the police-station, where the official announced that he was a warder from Portland Convict Prison in charge of John Lee, convict, on ticket-of-leave.

John Lee handed his ticket to the police officer, who read it.

What was it that made the policeman start as he read? What was it that made him look so curiously at the tall, thin, clean-shaven elderly man before him?

It was this: Certain particulars on the ticket showed that on February 4th, 1885, the bearer was sentenced to death at Exeter Assizes for murder at Babbacombe. The man was ‘Babbacombe’ Lee.

‘Babbacombe’ Lee was on his way to spend Christmas with his aged mother – John Lee, the man they could not hang, the man under whose feet the grim mechanism of the scaffold had mysteriously failed in its appointed work.

The story of his life’s ordeal John Lee himself will tell in the following pages. It is the story of one, who, rightly or wrongly, was doomed in the first flush of manhood to a torture more fiendish than the human mind, unaided by the Demon of Circumstances, could have devised. It is the story of a man dangled in the jaws of death, and hurried thence to a living tomb whose terrors make even death seem merciful.

From his terrible ordeal, John Lee emerges with the cry, ‘I am innocent’ still on his lips. And who that has not suffered will not listen?

Introduction to The Man They Could Not Hang, John Lee, 1908

Chapter 1

The lure of the sea

We came to Babbacombe, a small bay . . . It is a beautiful spot . . . Red cliffs and rocks with wooded hills like Italy and reminding one of a ballet or play where nymphs appear – such rocks and grottos, with the deepest sea on which there was no ripple.

– Queen Victoria’s Journal, 1846

When wealthy spinster Emma Keyse employed a rough country lad called John Lee to work on her South Devon coastal estate in 1878, she little realised that a relationship had been forged which would end in personal tragedy for her and criminal infamy for him. Many years later, he recalled their first meeting, when she assessed his suitability for a position in her household: ‘I went to Babbacombe. Just by the sea-shore was an old house called “The Glen,” and in that house lived the lady who was to be my mistress – Miss Keyse. I saw her with my mother. She seemed to be pleased with me, so pleased that she engaged me at once. I was to receive three shillings a week. What a happy day that was for me. If I had only known what was to happen afterwards!’ (Lee, 1908).

‘What was to happen afterwards’ resulted in John Lee being accused of launching a murderous attack on Emma Keyse. Police were called to her home in the early hours of the morning on Saturday 15 November 1884, and their suspicions were quickly aroused by the presence of the only male servant. Despite his plea of innocence, John Lee was found culpable and condemned in time-honoured fashion ‘to be taken to a place of execution and thereby hanged by the neck until dead’. Incredibly, the hangman was thwarted when the trapdoors of the scaffold resolutely refused to swing open beneath the feet of the condemned man. The attempt had to be abandoned and as a consequence, the death penalty was commuted to life imprisonment following the personal intervention of Queen Victoria.

John Lee.

The Queen was one of three British monarchs who had favoured The Glen with a visit. She was enraptured by the delights of Babbacombe, which was part of fashionable Torquay and renowned as ‘The Queen of the Watering Places’. The holiday resort first rose to prominence shortly after the Battle of Waterloo. In July 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte became an invaluable tourist attraction when he was held offshore by the Royal Navy en route to exile on the isle of St Helena. The town received the royal seal of approval in August 1833, when the Duchess of Kent and her fourteen-year-old daughter, Princess Victoria, attended a regatta and were greeted by a cheering crowd as the royal yacht landed unexpectedly at Torquay Harbour. Their Royal Highnesses were accommodated at a nearby hostelry, soon to be renamed the Royal Hotel by the proud proprietor, before continuing with the main purpose of their visit, making the short journey to Babbacombe. Their destination was the home of Emma Keyse and her twice-widowed mother, Elizabeth Whitehead, who had briefly served the royal family at a crucial moment in British history.

Princess Victoria in 1834.

At Christmas 1819, while residing in Sidmouth, Elizabeth helped to care for Princess Victoria when the infant’s debt-ridden parents fled from their London creditors and arrived in the East Devon resort where they were offered accommodation at Woolbrook Glen. During the royal family’s seven-week stay, there was consternation in the nursery when a boy fired his rifle at some birds in the garden. A coloured pane of glass now indicates the spot where a pellet crashed through a window and narrowly missed the head of the royal baby. Worse was to follow in January 1820, when Edward, the Duke of Kent, returned from a long walk in the rain. He delayed changing out of his wet clothes, preferring to spend some time playing with his baby daughter. As a result, he caught a feverish chill and developed pneumonia, from which he quickly died. Within a week, Victoria’s grandfather, ‘Mad’ King George III, was also dead, and with a lack of male heirs, the seven-month-old princess took an unwitting step towards eventually claiming the throne in 1837.

As Elizabeth Whitehead and the Duchess of Kent renewed their acquaintance over tea in the music room of The Glen, Princess Victoria, who was destined to become the nation’s longest-serving monarch, was kept company by her hostess’s seventeen-year-old daughter from her first marriage, Emma Keyse – the future victim of the infamous Babbacombe Murder.

She was born in 1816 at Edmonton, London, the youngest child of wealthy socialites Thomas and Elizabeth Keyse. Emma’s father died when she was aged only five, and her mother soon remarried another gentleman of independent means, George Whitehead. The family settled for some years on a country estate at Teigngrace, near the South Devon market town of Newton Abbot, but by 1830 they were living in Babbacombe, which was then a small fishing hamlet, thriving on plentiful catches of sprat and pilchard. The community grew around Babbacombe Beach, which had its own tavern, the Cary Arms, and a coastguard station with revenue officers monitoring the activities of local smugglers.

The room where Emma Keyse entertained Princess Victoria.

George Whitehead passed away in 1831 and was buried in the graveyard of the parish church in the neighbouring district of St Marychurch. Isambard Kingdom Brunel would later make a generous donation towards the rebuilding of the church. The Great Western Railway engineer bought land in the area while supervising the stretch of line between Exeter and Torquay. In 1854, he performed a tremendous service for Elizabeth Whitehead when he involved himself in a campaign to foil a plan to build a gas-works near her home on Babbacombe Beach. Following protests, the case went before a parliamentary committee where Brunel spoke eloquently against the proposal and won the day in the House of Lords. The local press triumphantly announced the victory: ‘Mr Brunel . . . succeeded, by the expression of his opinion and great influence, in driving the nuisance from Babbacombe’ (Pateman, 1991).

Emma Keyse’s two brothers and four sisters from her mother’s two marriages gradually left home to make their way in the world. Her sisters all married men of substance, while Emma remained a lifelong spinster. It is often said that she became a lady-in-waiting or matron of honour to Queen Victoria. This claim is totally unfounded, although she and her mother entertained royalty on a further occasion, when, in 1852, the royal yacht anchored in Babbacombe Bay. Queen Victoria stayed on board while her husband, Prince Albert, and their sons Prince Alfred and Albert the Prince of Wales were rowed to Babbacombe Beach. The young princes were entertained by Elizabeth Whitehead, while Emma Keyse had the honour of conducting the Prince Consort around the grounds of The Glen. As the royal party left Babbacombe, the landlord of the Cary Arms, William Gasking, presented the visitors with a copy of a lithograph depicting the royal yacht Victoria and Albert with a naval escort passing through Babbacombe Bay in 1846. On that occasion, bad weather had prevented the royal couple from landing. The Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) returned twice more to Babbacombe, in 1878 and 1880, and during the latter visit handed a half-sovereign to each of the household servants of Miss Keyse. The youngest of these was the cook Amelia Lee whose troublesome brother John would be accused of the seemingly senseless killing of Emma Keyse four years later.

A portrait of Emma Keyse on her twenty-first birthday.

Born on 15 August 1864 at Abbotskerswell, an agricultural village situated midway between Torquay and Newton Abbot, John Henry George Lee was the second child of John and Mary. He attended the village school with his sister Amelia, who was two years older. The children also had an elder half-sister, Elizabeth Harris, the illegitimate daughter of their mother, who was raised by her grandparents in the nearby village of Kingsteignton. All three children, known to the family as Jack, Millie and Lizzie, would at some point find employment in the service of Emma Keyse some years after she inherited the Glen estate upon the death of her mother in 1871.

The 13-acre estate extended from the rolling grassy cliff top of Babbacombe Downs to the shingle beach some 300 feet below. Access to and from the seashore was only possible on foot via an extremely steep winding track, and as she grew older, this may have been a factor in Emma Keyse’s decision to dispose of the property at auction shortly before her death. A later advertisement gives a graphic description of the splendour of the location. The principal residence mentioned is ‘The Vine’, while the cottage situated ‘immediately above the beach’ is where Emma Keyse chose to reside. Formerly known as ‘Beach House’, then ‘Babbicombe’ (an earlier derivation of the place name Babbacombe), it became forever remembered as simply ‘The Glen’:

The Glen on Babbacombe Beach (centre) with The Vine in the trees above.

Occupying one of the loveliest stations on the coast of Devon, and unequalled in its attractions as a yachting station. . . . This property has been several times visited and admired by the Queen and other members of the Royal family. The grounds comprise the whole of one side of a most picturesque Glen, and extend to the seashore. They are of singular beauty, and are well planted and tastefully laid out in shrubberies, woodland and wilderness walks, with winding paths leading to secluded nooks, commanding magnificent views of the coast scenery extending to Portland Bill, as well as of the far-famed Babbacombe Bay. There are also lawns, suitable for croquet or tennis, kitchen and other gardens.

The principal residence stands on a level plateau at a good elevation in a sheltered and charming situation. It contains lofty hall, drawing and dining rooms, each 27 feet in length; breakfast room, Nine Bedrooms and man servant’s room, good kitchen and offices; 3-stalled stable, loft, and coach house. Hard and soft waters are laid on. There is also a cottage situated on small level lawn immediately above the beach, approached by colonnade, and containing entrance hall, dining room pretty ante-room, conservatory, leading to a drawing room; handsome music or billiard room, 34 feet × 19ft. 6in. (detached), but connected with a main building by a covered passage; ten bedrooms and dressing rooms, and extensive cellarage. (Torquay Times, 23 August 1889)

The 1881 census shows that the property was occupied by Emma Keyse accompanied by two long-serving elderly maids, sisters Eliza and Jane Neck, a young gardener, Simon Bartlett, and the cook, Amelia Lee, who was soon to leave and be replaced by her half-sister Elizabeth Harris. At the age of fourteen, John Lee joined The Glen household shortly after the Prince of Wales had made a brief visit to Babbacombe in September 1878 (the date is incorrectly given as August 1879 in our illustration of the souvenir produced by the proprietor of the Cary Arms). The Prince was rowed to Babbacombe Beach and invited to tea by Miss Keyse, but arrangements had been made for him to dine alfresco at the Cary Arms. By the time the Prince of Wales returned with his wife, Princess Alexandra, and their two sons, Prince Albert Victor and Prince George (the future King George V), in May 1880, John Lee had left the household, albeit temporarily.

With royal visitors in the habit of turning up unannounced, a spare bedroom at The Glen called the ‘Honeysuckle Room’, and dubbed the ‘Queen’s Room’ by the household servants, was kept in constant readiness in case a member of the royal family required overnight accommodation. There was no such luxury, however, for the lowly servant John Lee, who slept downstairs on a fold-down bed in the pantry. He had been offered employment by Miss Keyse when she required someone to work in the stables: ‘So there I was in my first situation. I had nothing much to do. The pony was about thirty years old, I believe. They told me that it once belonged to my mistress’s mother, and that it had been more or less pensioned off for its old age. I had to look after it just as one would nurse some infirm creature. I put it in its stable at night or took it out for exercise. When I was not looking after the pony I was generally going about with Miss Keyse. When she went visiting I used to bring her home at night. I was the boy’ (Lee, 1908).

An alfresco picnic at the Cary Arms.

Cary Arms souvenir of royal visits to Babbacombe.

The grandeur of The Glen was quite a change of surroundings for the son of a clay miner raised in a small rented cottage in a relatively poverty-stricken village. The Great Western Illustrated Railway Guide from this period carries this description of Babbacombe, which then had a population of around 1,000 people:

From Babbacombe Downs, where the best houses are to be found, one of the most delightful of the delightful views in South Devon is to be found. The eyes wander along the eastern coast to Teignmouth, Starcross, over the Exe to Exmouth, and past this point to those of Budleigh Salterton and Sidmouth. The rich dark red of the rocks, the deep tone of the sea, and the brilliant green of the meadows topping the undulating cliffs form, with the vast expanse of the sky, a most lovely panorama. Below, lies the well-sheltered beach, whence our view, looking eastward, is taken. Here the waters are clear as crystal, and splash over an expanse of such well-rounded pebbles, that the bather is guaranteed from injury. To the eastward rises a mass of roseate rock, while to the right lies the undercliffe, where the closely-sheltered houses promise a pleasant refuge for the invalid. . . . Above, on the breezy downs, quite a town may now be seen, and here, visitors seeking invigorating sea-side air, may readily find it, while sojourning in houses well guaranteed from extreme heat, even in the hottest weather.

A GWR sketch showing The Glen on Babbacome Beach.

Babbacombe possesses the advantage of being rural and retired, while it is only a drive of two or three miles over a road (which is a perfect avenue of fine trees), and by the sea-wall, into charming Torquay. The walks east and west over the downs are unparalleled. Indeed, Babbacombe, with its lofty rocks, its beetling cliffs, and its masses of deep shadowy foliage, is a place to be remembered.

Living and working in this wonderful setting, John Lee was inspired to see more of the world as he became captivated by the lure of the sea:

I ought to explain that Babbacombe was a prosperous fishing village. The place was full of old sailors, who used to tell me queer yarns. All kinds of strange craft used to come in and anchor in the bay. They were mainly small trading vessels, but every now and then a big man-of-war, one of the old-fashioned kind – would come in, and then I used to spend the whole afternoons on the beach, watching the ships and jack tars.

Time went on, and every day I became more and more fascinated with a new idea that had taken possession of me. I would be a sailor. (Lee, 1908)

Following heated arguments, John overcame considerable opposition from his father and got his wish, joining the Royal Navy on 1 October 1879. Initially, all went well in his new career as he was stationed on a succession of training ships at Plymouth. At Christmas 1880, he was awarded a book, The Bear Hunters of the Rocky Mountains by Anne Bowman, in recognition of his success, receiving the ‘Admiralty Prize for general progress. First prize, first instruction’. However, in January 1882, his dream of going to sea and travelling to exotic countries was dashed. At the age of eighteen, Lee’s life in the Royal Navy came to a sudden end when he was taken seriously ill:

I was stricken down with pneumonia, and sent to the Royal Naval Hospital. For some days I lay between life and death till they pulled me through – but at what a price!

The doctors told me that I was of no more use to the Navy. I was invalided out. My career was closed. I still possess my discharge papers, setting forth the reason of my discharge and describing my character as ‘Very good.’

My heart was broken. There seemed to be nothing left for me to do. (Lee, 1908)

This setback was the crucial event in what Lee described as ‘a clutch of circumstances’ that were to lead the would-be sailor back to The Glen and criminal notoriety two years later. That fateful year ‘A Visitor’s Opinion of Torquay’, which was first published in the Cheltenham Examiner, was proudly reproduced in the Torquay Directory, 27 August 1884:

Invalids resting outside the Cary Arms.

‘Anywhere, anywhere out of the town,’ was the scattering cry this month among the remnant left in London of the nomadic band known as Society. As chronicler of that favoured corporation, our vocation was at an end, and we ‘did’ Torquay. . . . It does not boast the bracing qualities of the more favoured northern resorts, but for those who do not require to be strung up to a muscular pitch, who are in a normal state of good health, and who merely wish for quiet, cool sea breeze, beautiful drives, objects of romantic and historic interest within a day’s outing, every luxury and refinement that the 19th century can give, moderate charges for housing of every degree, and good boating, Torquay holds its own against any other sea-coast place in England. For those too delicate or fragile to brave sharper air, it stands alone.

The season of Torquay, as everybody knows, is winter – then it is crowded with rich invalids, and also with pleasure seekers, young and old – and prices rise in proportion. Then the great hotels are crowded, and the sheltered villas, peering out on the sea from quiet leafy nooks, find ready tenants. Now the same accommodation can be had for probably one half the winter charge. The appliances for warding off the cold winds of winter and spring also ward off the too ardent regards of the sun – and for summer residences the houses are charming. . . . The drive to Babbacombe, a suburb, and now almost part and parcel of Torquay proper, gives some lovely sea views. . . . The sojourner there could make a separate excursion each day for a month to some place of interest, and still leave the field un-exhausted. . . . Torquay has one more recommendation; it enjoys an immunity from severe thunder-storms.

This flattering testimonial of the delights of the area provided excellent publicity for the fast-growing holiday resort, although bad news was soon to follow. That winter Torquay hogged the headlines with lurid details of a dastardly crime. Furthermore, the assertion of the Cheltenham Examiner that the town enjoyed an ‘immunity from severe thunder-storms’ proved to be a fallacy when All Saints Church, Babbacombe, and St Marychurch Parish Church were struck by lightning on 30 January 1885. Perhaps this was an omen of things to come, for the date coincided with the opening of the Devon County Assizes at Exeter Castle and the eagerly awaited trial of the man accused of committing the vile and despicable ‘Babbacombe Murder’.

Chapter 2

Troubles and misfortunes

The tragedy, by whomsoever enacted, has put an end to the philanthropic exertions of Miss Keyse on behalf of the prisoner Lee.

– Torquay Directory, 26 November 1884

John Lee described his youth as a ‘long series of troubles’ and ‘misfortunes’. These began at the age of eighteen, when he was forced to relinquish his naval career on health grounds and return to South Devon to seek alternative employment. In the first nine months of 1882, he moved between three jobs. The first, and longest, period was spent in a position as ‘boots’, cleaning the footwear of guests at the Yacht Club Hotel, Kingswear. Dissatisfied with this lowly occupation, he gained employment as a porter at Kingswear Railway Station; then, a month later, early in October, was transferred to the goods department at Torre Station, Torquay. He had only been there one week when fate intervened in the shape of his former employer Emma Keyse who presented him with a golden opportunity to further his prospects: ‘Miss Keyse had been keeping an eye on me. She used to write to me and give me good advice. You can understand, therefore, how one morning my heart positively leapt for joy when I received a letter from her in which she told me that she had arranged for me to go as footman to Colonel Brownlow at Torquay. I gratefully accepted the offer, entered the colonel’s service – and happened on my second great misfortune’ (Lee, 1908).

Lee’s ‘second great misfortune’ was a self-inflicted act of crass stupidity committed only six months later, when he stole valuables from his new employer, the Brownlows, while they were holidaying abroad. The young servant was apprehended in Plymouth attempting to pawn the family silver. Victorian moral values were harsh, and his crime virtually ensured that Lee would never again be employed in a position of trust. The case came before the magistrates at Torquay Police Court on Wednesday 9 May, lasted two days and warranted prominent coverage in the Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser (Torquay Times), Saturday 12 May 1883:

John Lee, footman, was charged with stealing a quantity of silver plate belonging to his employer, Colonel Brownlow, of Ridgehill, Middle Warberry Road. Mr. Creed, solicitor, defended.