Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

PREFACE

Table of Figures

Acknowledgements

CHRONOLOGY

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE - A COUNTRY BOY

CHAPTER TWO - PINS AND STRING

CHAPTER THREE - PHILOSOPHY

CHAPTER FOUR - LEARNING TO JUGGLE

CHAPTER FIVE - BLUE AND YELLOW MAKE PINK

CHAPTER SIX - SATURN AND STATISTICS

CHAPTER SEVEN - SPINNING CELLS

CHAPTER EIGHT - THE BEAUTIFUL EQUATIONS

CHAPTER NINE - THE LAIRD AT HOME

CHAPTER TEN - THE CAVENDISH

CHAPTER ELEVEN - LAST DAYS

CHAPTER TWELVE - MAXWELL’S LEGACY

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Table of Figures

Figure 1 Maxwell’s colour triangle

Figure 2a . Switch open

Figure 2b . Switch first closed

Figure 2c . Shortly after switch closed

Figure 2d . Switch opened again

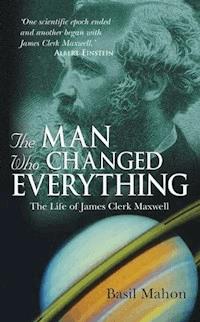

James Clerk Maxwell. From a bronze bust by Charles D’Orville Pilkington Jackson. Courtesy of the University of Aberdeen

Published in the UK in 2003 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777ephone (+44) 1243 779777

Email (for orders and customer service enquiries):

[email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2003 Basil Mahon

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to

[email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620.ed to (+44) 1243 770620.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Basil Mahon has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Other Wiley Editorial Offices

John Wiley & Sons Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

Jossey-Bass, 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741, USA

Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Boschstr. 12, D-69469 Weinheim, Germany John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd, 33 Park Road, Milton, Queensland 4064, Australia

John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2 Clementi Loop #02-01, Jin Xing Distripark, Singapore 129809

John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd, 22 Worcester Road, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada M9W 1L1 Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0-470-86088-X

Typeset in 10 /13 pt Photina by Mathematical Composition Setters Ltd, Salisbury, Wiltshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall. This book is printed on acid-free paper responsibly manufactured from sustainable forestry in which at least two trees are planted for each one used for paper production.

DEDICATION

To Ann

PREFACE

I fell under Maxwell’s spell when I was about 16 but for more than 40 years he was a man of mystery. His name cropped up in all the popular accounts of twentieth century discoveries such as relativity and quantum theory, and when I became an engineering student I learnt that his equations were the fount of all knowledge in electromagnetism. They seemed to work by magic—something I attributed, with good grounds, to imperfect understanding. But now that I understand the equations a little better they seem even more magical.

Over the years the spell tightened its grip. My extensive, if desultory, reading on scientific matters served to deepen the mystery. Usually introduced as ‘the great James Clerk Maxwell’, his influence on the physical sciences seemed to be all-pervasive. Yet he was scarcely known in the wider world; most of my friends and colleagues had never heard of him, although all knew of Newton and Einstein and most knew of Faraday. What is more, nothing in what I had read revealed much about Maxwell’s life beyond the bare facts that he was Scottish and lived in the mid-nineteenth century.

The time had come to unravel the mystery. A few years ago I looked him up in all the reference books I could find, starting in the local library. The Encyclopaedia Britannica had a helpful 2000 word entry and a short bibliography. It was like finding the way to a store of buried treasure. Maxwell was not only one of the most brilliant and influential scientists who ever lived but an altogether fine and engaging man. And he seemed to inspire in writers a unique combination of wonder and affection; a Times Literary Supplement editorial of 1925, preserved in Trinity College Library, sums it up by saying that Maxwell was ‘to physicists, easily the most magical figure of the nineteenth century’.

I have tried to tell the story simply and directly, putting the reader at Maxwell’s side, seeing the world from his perspective as his life unfolds. Hence the main narrative contains few references to sources and no more background or detail than is needed for the story. The separate Notes section attends to these aspects and gives some interesting sidelights.

To his friends, and he had many, Maxwell was the warmest and most inspiring of companions. I hope this book will leave readers glad that they, too, know him a little.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Anyone who writes, or indeed reads, about Maxwell owes a great debt to Lewis Campbell, who gave us an affectionate yet penetrating picture of his lifelong friend in The Life of James Clerk Maxwell, co-written with William Garnett and published 3 years after Maxwell’s death. Campbell and Garnett’s book has been the principal source of information for all subsequent biographies and I would like to add my tribute and my thanks to those given by other authors.

I am also much indebted to the more recent biographers Francis Everitt, Ivan Tolstoy and Martin Goldman for their added insights, to Daniel Siegel and Peter Harman for their scholarly but reader-friendly analyses of Maxwell’s work, and to the other authors listed in the bibliography. Several patient friends have kindly read drafts and suggested improvements; among these I am particularly grateful to Harold Allan and Bill Crouch. John Bilsland supplied excellent line drawings for the figures, and David Ritchie and Dick Dougal located many of the sources for the illustrations.

The Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh gave valuable help, as did the Royal Institution of Great Britain, King’s College London, the University of Aberdeen, Trinity College Cambridge, the University of Cambridge Department of Physics, Cambridge University Library, the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Institution of Electrical Engineers and Clifton College.

A visit to Maxwell’s birthplace at 14 India Street, Edinburgh, is a moving experience for anyone with an interest in Maxwell. It is possible only because the trustees of the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation service acquired the house in 1993 and have with trouble and care created a small but evocative museum. I should like to thank them for this service.

I am especially grateful to Sam Callander and to David and Astrid Ritchie for their generous encouragement and kindness.

The final words of thanks go to Wiley for publishing the book, and especially to my editor Sally Smith and her assistant Jill Jeffries for their friendly and expert help and guidance.

CHRONOLOGY

Principal events in Maxwell’s life

1831Born at 14 India Street, Edinburgh, 13 June. Grew up at Glenlair1839His mother, Frances, died1841Started school, Edinburgh Academy1846Published his first paper, on oval curves1847Started at University of Edinburgh1848Published paper On Rolling Curves1850Published paper On the Equilibrium of Elastic SolidsStarted at Cambridge University, Peterhouse for one term, then Trinity1854Finished undergraduate studies at Cambridge: second wrangler, joint winner of Smith’s Prize: started post-graduate work1855Published paper Experiments on Colour as Perceived by the EyePublished first part of paper On Faraday’s Lines of Force, second part the following year Elected Fellow of Trinity1856His father, John, died Appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College, Aberdeen1858Awarded Adams’ Prize for essay On the Stability of the Motion of Saturn’s Rings, paper published 18591858Married Katherine Mary Dewar, daughter of Principal of Marischal College1860Published papers Illustrations of the Dynamical Theory of Gases and On the Theory of Compound Colours and the Relations of the Colours of the SpectrumMade redundant from Marischal College Failed in application for Chair of Natural Philosophy at University of EdinburghSeverely ill from smallpoxAppointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at King’s College, LondonAwarded Rumford Medal by the Royal Society of London for his work on colour vision1861Produced world’s first colour photograph Published first two parts of paper On Physical Lines of Force, the remaining two parts the following yearElected FRS1863Published recommendations on electrical units and results of experiment to produce a standard of electrical resistance in his Committee’s report to the British Association for the Advancement of Science1865Published paper On Reciprocal Figures and Diagrams of Force Published paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic FieldSeverely ill from infection from cut sustained in riding accidentResigned chair at King’s College London; returned to live at Glenlair1866Published paper On the Viscosity or Internal Friction of Air and Other Gases1867Published paper On the Dynamical Theory of Gases Visited Italy1868Published paper On GovernorsCarried out experiment to measure the ratio of the electrostatic and electromagnetic units of charge, which by his theory was equal to the speed of lightApplied for but failed to get post of Principal of St Andrews University1870Published paper On Hills and Dales Awarded Keith Medal by the Royal Society of Edinburgh for work on reciprocal diagrams for engineering structures1871Published book The Theory of Heat, in which he introduced Maxwell’s demonAppointed Professor of Experimental Physics at Cambridge UniversitySupervised design and construction of Cavendish Laboratory building (fully operational 1874)1873Published book A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism1876Published book Matter and Motion1879Published paper On Boltzmann’s Theorem on the Average Distribution of a Number of Material PointsPublished paper On Stresses in Rarefied Gases Arising from Inequalities in TemperaturePublished book Electrical Researches of the Honourable Henry CavendishDied at Cambridge 5 November; buried at PartonNote:Maxwell published five books and about 100 papers. Those of his writings that are described in the narrative are listed here and are available, with others, under titles listed in the Bibliography.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Maxwell’s relations and close friends

Blackburn, Hugh: Professor of Mathematics at Glasgow University, husband of Jemima.

Blackburn, Jemima (née Wedderburn): James’ cousin, daughter of Isabella Wedderburn

Butler, Henry Montagu: student friend at Cambridge, afterwards Headmaster of Harrow School and, later, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge

Campbell, Lewis: schoolfriend, afterwards Professor of Greek at St Andrews University

Campbell, Robert: younger brother of Lewis

Cay, Charles Hope: James’ cousin, son of Robert

Cay, Jane: James’ aunt, younger sister of Frances Clerk Maxwell

Cay, John: James’ uncle, elder brother of Frances Clerk Maxwell

Cay, Robert: James’ uncle, younger brother of Frances Clerk Maxwell

Cay, William Dyce: James’ cousin, son of Robert

Clerk, Sir George: James’ uncle, elder brother of John Clerk Maxwell

Clerk Maxwell, Frances (née Cay): James’ mother

Clerk Maxwell, John: James’ father

Clerk Maxwell, Katherine Mary (née Dewar): James’ wife

Dewar, Daniel: James’ father-in-law, Principal of Marischal College, Aberdeen

Dunn, Elizabeth (Lizzie) (née Cay): James’ cousin, daughter of Robert Cay

Forbes, James: friend and mentor, Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University, afterwards Principal of St Andrew’s University

Hort, Fenton John Anthony: student friend at Cambridge, afterwards a professor at Cambridge

Litchfield, Richard Buckley: student friend at Cambridge, afterwards Secretary of the London Working Men’s College

Mackenzie, Colin: James’ cousin once removed, son of Janet Mackenzie

Mackenzie, Janet (née Wedderburn): James’ cousin, daughter of Isabella Wedderburn

Monro, Cecil James: student friend at Cambridge, afterwards a frequent correspondent with James, particularly on colour vision

Pomeroy, Robert Henry: student friend at Cambridge who joined the Indian Civil Service and died in his 20s during the Indian Mutiny

Tait, Peter Guthrie: schoolfriend, afterwards Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University

Thomson, William, later Baron Kelvin of Largs: friend (and mentor in early stages of James’ career), Professor of Natural Philosophy at Glasgow University

Wedderburn, Isabella (née Clerk): James’ aunt, younger sister of John Clerk Maxwell

Wedderburn, James: James’ uncle by marriage, husband of Isabella

Note: The list shows those of Maxwell’s relations and close friends who are mentioned in the narrative, and two more who are included to explain relationships. His work colleagues and associates are not listed here, apart from Forbes, Tait and Thomson.

INTRODUCTION

One scientific epoch ended and another began with James Clerk Maxwell

Albert Einstein

From a long view of the history of mankind—seen from, say, ten thousand years from now—there can be little doubt that the most significant event of the nineteenth century will be judged as Maxwell’s discovery of the laws of electrodynamics.

Richard Feynmann

In 1861, James Clerk Maxwell had a scientific idea that was as profound as any work of philosophy, as beautiful as any painting, and more powerful than any act of politics or war. Nothing would be the same again.

In the middle of the nineteenth century the world’s best physicists had been searching long and hard for a key to the great mystery of electricity and magnetism. The two phenomena seemed to be inextricably linked but the ultimate nature of the linkage was subtle and obscure, defying all attempts to winkle it out. Then Maxwell found the answer with as pure a shaft of genius as has ever been seen.

He made the astounding prediction that fleeting electric currents could exist not only in conductors but in all materials, and even in empty space. Here was the missing part of the linkage; now everything fitted into a complete and beautiful theory of electromagnetism.

This was not all. The theory predicted that every time a magnet jiggled, or an electric current changed, a wave of energy would spread out into space like a ripple on a pond. Maxwell calculated the speed of the waves and it turned out to be the very speed at which light had been measured. At a stroke, he had united electricity, magnetism and light. Moreover, visible light was only a small band in a vast range of possible waves, which all travelled at the same speed but vibrated at different frequencies.

Maxwell’s ideas were so different from anything that had gone before that most of his contemporaries were bemused; even some admirers thought he was indulging in a wild fantasy. No proof came until a quarter of a century later, when Heinrich Hertz produced waves from a spark-gap source and detected them.

Over the past 100 years we have learnt to use Maxwell’s waves to send information over great and small distances in tiny fractions of a second. Today we can scarcely imagine a world without radio, television and radar. His brainchild has changed our lives profoundly and irrevocably.

Maxwell’s theory is now an established law of nature, one of the central pillars of our understanding of the universe. It opened the way to the two great triumphs of twentieth century physics, relativity and quantum theory, and survived both of those violent revolutions completely intact. As another great physicist, Max Planck, put it, the theory must be numbered among the greatest of all intellectual achievements. But its results are now so closely woven into the fabric of our daily lives that most of us take it wholly for granted, its author unacknowledged.

What makes the situation still more poignant is that Maxwell would be among the world’s greatest scientists even if he had never set to work on electricity and magnetism. His influence is everywhere. He introduced statistical methods into physics; now they are used as a matter of course. He demonstrated the principle by which we see colours and took the world’s first colour photograph. His whimsical creation, Maxwell’sdemon—a molecule-sized creature who could make heat flow from a cold gas to a hot one—was the first effective scientific thought experiment, a technique Einstein later made his own. It posed questions that perplexed scientists for 60 years and stimulated the creation of information theory, which underpins our communications and computing. He wrote a paper on automatic control systems many years before anyone else gave thought to the subject; it became the foundation of modern control theory and cybernetics. He designed the Cavendish Laboratory and, as its founding Director, started a brilliant revival of Cambridge’s scientific tradition which led on to the discoveries of the electron and the structure of DNA.

Some of his work gave direct practical help to engineers. He showed how to use polarised light to reveal strain patterns in a structure and invented a neat and powerful graphical method for calculating the forces in any framework; both techniques became standard engineering practice. He was also the first to suggest using a centrifuge to separate gases.

Maxwell was born in 1831 and lived for 48 years. A native Scotsman, he spent about half of his working life in England. From his earliest days he was fascinated by the world and determined to find out how it worked. Like all parents, his were assailed with questions, but to be interrogated by 3 year-old James must have been an experience of a different order. Everything that moved, shone or made a noise drew the question ‘What’s the go o’ that?’ and, if he was not satisfied, the follow-up ‘but what’s the particular go of it?’. A casual comment about a blue stone brought the response ‘but how d’ye know it’s blue?’. Maxwell’s childish curiosity stayed with him and he spent most of his adult life trying to work out the ‘go’ of things. At the task of unravelling nature’s deep secrets he was supreme.

Those in the know honour Maxwell alongside Newton and Einstein, yet most of us have never heard of him. This is an injustice and a mystery but most of all it is our own great loss. One excellent reason for telling this story is to try to gain Maxwell a little of the public recognition he so clearly deserves, but a much better one is to try to make good the loss. His was a life for all of us to enjoy. He was not only a consummate scientist but a man of extraordinary personal charm and generous spirit: inspiring, entertaining and entirely without vanity. His friends loved and admired him in equal measure and felt better for knowing him. Perhaps we can share a tiny part of that experience.

CHAPTER ONE

A COUNTRY BOY

Glenlair 1831-1841

When they had their first glimpse of the newcomer, the boys of the second year class could scarcely contain their hostile curiosity. He was wearing an absurd loose tweed tunic with a frilly collar and curious square-toed shoes with brass buckles, the like of which had never been seen at the Edinburgh Academy. At the first break between lessons they swarmed around the new boy, baiting him unmercifully, and when he answered their taunts in a strange Galloway accent they let out whoops of jubilant derision. At the end of a long day he arrived home with clothes in tatters. He seemed to be dull in class and soon acquired the nickname ‘Dafty’. The rough treatment went on, yet he bore it all with remarkable good humour until one day, when provoked beyond endurance, he turned on his tormentors with a ferocity that astonished them. They showed him more respect after that, but the name ‘Dafty’ stuck. So started the academic career of one of the greatest scientists of all time, James Clerk Maxwell.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!