5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

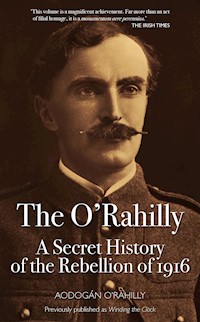

Although commemorated by Yeats's poem, Michael O'Rahilly is one of the forgotten leaders of the 1916 Rising — the first leader to die, the only one killed in action. This is his story written by his son, beginning in Ballylongford, County Kerry. O'Rahilly was educated at Clongowes, married a Philadelphia heiress, and had a brief career as a country gentleman and JP. O'Rahilly spent several years in the USA, returning in 1909 to Dublin, writing for the Sinn Féin press and joining the Gaelic League. Until his death, he devoted himself to the achievement of his country's independence. The O'Rahilly, as he became known, was the prime mover in the formation of the Irish Volunteers and its director of arms, organizing the purchase and delivery of the Howth rifles in July 1914. During Easter Week itself he acted as Pearse's aide-decamp in the General Post Office, and after Connolly was wounded became effective commander of the garrison. He died leading twelve men in a charge against a British barricade in Moore Street. Aodagán O'Rahilly was twelve when his father was killed, a privileged spectator of events that had the simplicity, and inevitability, of Greek tragedy. A final letter from son to father was endorsed by a dying soldier's farewell to his wife, punctured by the fatal bullet. This is the last personal account of 1916, honouring tradition that led to the founding of the Irish state, while saluting an individual who made it possible. It contains telling sketches of other actors in the drama — Casement, MacNeill, Redmond, Devoy, Hobson, Plunkett, Markievicz, Childers, Griffith, Pearse, Connolly — and by weaving unpublished documents and family letters through the narrative, clothes the skeleton of history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The O’Rahilly

A Secret History of the Rebellion of 1916

AODOGÁN O’RAHILLY

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

To My Mother

Sing of the O’Rahilly,

Do not deny his right;

Sing a ‘the’ before his name;

Allow that he, despite

All those learned historians,

Established it for good;

He wrote out that word himself,

He christened himself with blood.

How goes the weather?

Sing of the O’Rahilly

That had such little sense

He told Pearse and Connolly

He’d gone to great expense

Keeping all the Kerry men

Out of that crazy Fight;

That he might be there himself

Had travelled half the night.

How goes the weather?

‘Am I such a craven that

I should not get the word

But for what some travelling man

Had heard I had not heard?’

Then on Pearse and Connolly

He fixed a bitter look:

‘Because I helped to wind the clock

I come to hear it strike.’

How goes the weather?

What remains to sing about

But of the death he met

Stretched under a doorway

Somewhere off Henry Street;

They that found him found upon

The door above his head

‘Here died the O’Rahilly.

R.I.P.’ writ in blood.

How goes the weather?

(W.B. Yeats, ‘The O’Rahilly’)

Contents

Foreword to The O’Rahilly: A Secret History of the Rebellion of 1916

Preface

1. The Background of the Clan

2. Family and School Influences

Illustration Section One

3. Courtship and Marriage

4. Entry into Politics

Illustration Section Two

5. The Gaelic League

6. The Royal Visit

Illustration Section Three

7. A Call to Arms

8. The Ulster Volunteers

9. The Irish Volunteers

10. Redmond Becomes Involved

Illustration Section Four

11. Arming the Volunteers

12. World War I

13. England’s Difficulty, Ireland’s Opportunity

14. Casement Abroad

Illustration Section Five

15. The Die is Cast

16. Five Days that Transformed Ireland

Illustration Section Six

APPENDIX1:Manifesto on Behalf of The Gaelic League (Ireland), 1911; (Written by Michael O’Rahilly)

APPENDIX2:Redmond’s Ultimatum

APPENDIX3:Letter to the Workers’Republic

APPENDIX4:Connolly’s ‘Order of the Day’

APPENDIX5:From Nell Humphreys’ Letter to Nora

APPENDIX6:Eoin MacNeill and the Rising

APPENDIX7:Documents Relative to the Sinn Féin Movement; Sources

Copyright

Foreword toThe O’Rahilly: A Secret History of the Rebellion of 1916

Whether or not history and hindsight eventually elevate the Easter Rising to heroism or histrionics, we must remain curious about its principal instigators – those men and women whose names endure in the titles of streets, hospitals and train stations. This book offers an invaluable insight into one of these leaders, a figure who has been, in turn, overlooked and over-mythologized. Michael O’Rahilly stands out even among the panoply of burnished Irish revolutionary leaders – most of whom have been accorded attributes more fitting to the leading character of a romantic novel: the lovelorn son of a papal count, dying of tuberculosis; the shy school teacher with theatrical ambitions; the wily old prison-hardened Fenian who signs up for one last job with his innocent young protégé, a polio-blighted cripple with a valiant heart.

Among those many different individuals who all found their heart and soul on the road towards rebellion, Michael Joseph O’Rahilly makes for a curious anomaly – as the only leader, aside from Roger Casement, who desperately did not want the Easter Rising to happen and actively tried to prevent it … yet who, with glorious irony, ends up being the single senior officer killed in action during the fighting.

O’Rahilly, a debonair, dashingly dressed, knightly figure, was also a visionary inventor, an affluent anti-capitalist, a skilled furniture-maker, a successful newspaper editor, an able graphic designer and an accomplished tenor renowned for recitations at distinguished social gatherings. While a life of family stability lay before him, he chose instead to turn his back on privilege, selling his yacht and racehorse to devote himself to the ideal of political freedom and the creation of a nation with integrity and vision. He went about the mission with the same vigour with which he had previously worked the stock exchange, promoted the aviation industry, and run a woollen mill in Philadelphia. He immersed himself first of all in the intricacies of British military strategies, so that he might beat them at their own game, and then went to Europe to buy up as many guns as he could afford and had them smuggled to Ireland.

It’s a heady story, particularly for me, a great-grand-nephew of The O’Rahilly, who was reared on my grandmother’s account of how on Easter Monday 1916 she watched her Uncle Michael dress in his finest officer’s uniform of Irish wool, his puttees and knee-high leather boots, before heading out to sacrifice his life in a fight that he knew was bound to fail. As co-founder of the Irish Volunteers and director of military operations he realized the British would kill him for his actions. He bade a final farewell to Nancy, his young American wife, who was seven months pregnant with their fifth child, as my grandmother, Sighle (Humphreys) O’Donoghue, took the youngest of his four sons for a walk to Sandymount. The words he wrote to Nancy as he lay dying five days later echoed through my childhood: ‘I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street. I got more [than] one bullet, I think. Tons and tons of love Dearie to you and the boys. It was a good fight anyhow.’

This book by Aodogán O’Rahilly, Michael’s second surviving son, is part biography, part paean to a beloved father, containing much solid historical fact and insight. Its title, incidentally, has been changed in this republication from the original Winding the Clock: O’Rahilly and the 1916 Rising (The Lilliput Press, 1991) to the current title, The O’Rahilly: A Secret History of the Rebellion of 1916, for which Aodogán, who died in 2000, had originally expressed a preference. Aodogán spent two decades researching the book, consulting every library and archive to which he could arrange access. He beavered through dusty files and badgered archivists in search of documents that he intuited must exist or had heard rumours about. His notes filed amongst The O’Rahilly Papers in UCD archives reveal the many valuable accounts he brought to light through his research. There was diligence and deliberation in his methods, not to mention generosity: I was paid handsomely as a teenager to collate my grandmother’s papers in the hopes that they might throw up some useful nugget.

Yet, it must be taken into account that Aodogán was eleven when his father died and that for the rest of his life he remained enchanted by his martyred father. One must therefore indulge his tendency to position The O’Rahilly centre stage in every scene. The book presents a convincing case for Michael O’Rahilly as the singular key figure in the formation of the Volunteers and the subsequent lead-up to the Rising, and while this is not entirely inaccurate, the tight focus on a particular individual does skew the reality a bit. Other events and people are sidelined. There’s a tendency at times to gild the lily and to romanticize, with family anecdotes being given equal status to documentary evidence, but this just adds to the readability of the work. In the literature of Irish twentieth-century national history, Ernie O’Malley’s On Another Man’s Wound and James Stephens’ The Insurrection in Dublin are apt equivalents, emphasizing story rather than arid historical accuracy.

In some respects, Aodogán is as intriguing a character as his father – a gallant, single-minded visionary who devoted his life to realizing the full manifestation of his father’s dream: first, fighting in the IRA during the Civil War, then establishing the Weatherwell Tile factory, so that Ireland could be independent in its building supplies. He contested a Dáil seat for Fianna Fáil in 1932 and, when unsuccessful, decided to turn his back on politics (despite de Valera’s entireties to remain) and devoted his energies to developing the nation in more tangible ways: planting one of the largest private forestry plantations in Ireland and pioneering the production of peat as a director of Bord na Móna for almost forty years – both issues that his father had attempted to develop before him. He married an affluent and dynamic Irish-American, just as his father had done, and set about establishing a thriving import/export business by buying and rejuvenating Greenore Port in County Louth, clearly aware of how his father’s direct link to international shipping routes via the Shannon had helped the family pub and shop in Ballylongford, County Kerry, amass the then large sum of £25,000 by 1896. Aodogán himself was to spend many years, from the mid seventies to the late eighties, researching and writing this book.

No matter what your perspective, the fact that a small disparate group of mostly determined romantics took on the pan-global might of the British Empire in Easter 1916 is an intriguing incident. It was a ridiculous, valiant and visionary act, or as O’Rahilly told Countess Markievicz on the Easter Monday, ‘It is madness, but it is a glorious madness.’

The search for identity and meaning that led to that moment is as relevant to us now as it was then, and in so far as this book casts light on an individual who regarded Irish culture and heritage as a palpable, living entity worth sacrificing everything for, it has an urgency beyond most history books. By declaring that the Easter Rising should not proceed and actively trying to prevent it, The O’Rahilly cast himself on the wrong side of history and was eclipsed for a century. Perhaps this twenty-fifth anniversary re-issue of Aodogán’s book may redress the balance.

Manchán Magan, Collinstown,

County Westmeath, January 2016

Preface

This is the story of a young Irishman who believed that the British would not release their grip on Ireland until they were compelled to do so by being defeated in an armed struggle. It tells how he came to this conclusion and of the steps he then took to make the armed struggle possible. It may be of interest to historians of the period from 1910 to 1916 and to Irish people who are curious about the pressures that finally led to the withdrawal of the British army of occupation from twenty-six of the Irish counties.

The armed struggle to compel the British to release their grip on Ireland is not now a popular doctrine. Nor was it when it was first proposed to the Irish people almost eighty years ago. In 1912 Michael O’Rahilly urged the men of Ireland to arm themselves if they wished to free themselves from British domination. What he had in mind was that the Home Rule Bill had been passed by the House of Commons and could be delayed by the House of Lords for only two years. This meant that there would then be a Home Rule Parliament in Dublin.

This Irish Parliament would have no army, but if a body of Irish Volunteers was under its control, there was nothing the British government could do to disband it. It would have to be a ‘volunteer’ army because the Irish government would have no power to raise revenue to pay a regular army, and the British government was not likely to provide funds for this purpose. Such an armed force, under the control of the Home Rule Parliament in Dublin, would be as effective as a regular army. It was just such a force of Volunteers in 1782 that enabled that Irish Parliament to obtain substantial concessions from the British government. O’Rahilly’s call to the manhood of Ireland in 1912 went unheeded. But less than twelve months later the Ulster Volunteers were organized to resist, if necessary by force of arms, the passionate desire of eighty per cent of the Irish people for a Home Rule government, to look after Irish interests. This Irish Home Rule Bill had been enacted by a majority of the Westminster House of Commons, but, despite this, Carson, with the support of senior members of the British Conservative Party, was recruiting a volunteer army to resist its enactment.

Those people who now issue routine denunciations of the ‘men of violence’ should spare a passing malediction for Carson and Bonar Law and the leading members of the British Conservative establishment, who in 1913 financed, organized and gave their full support to a minority whose doctrine was that if they could not achieve what they wanted by normal political activity, they were endued to take to the gun and obtain their objectives by the bomb and the bullet.

The existence of Carson’s Ulster Volunteers made it easy for O’Rahilly to convene, at the end of 1913, the meeting that led to the formation of the Irish Volunteers. These Volunteers made the rebellion of Easter 1916 possible. This biography spells out how O’Rahilly set about calling this meeting and forming the Irish Volunteers.

For many years following 1916 there was a general belief that the Rising was an event of which Irish people could be proud, but in recent times a ‘revisionist’ school of historians has been promulgating its conviction that, on the contrary, the Irish should be ashamed of it and should try to dissociate themselves from any approval or pride in it. Whether we approve or disapprove, there is general acceptance that the Rising of 1916 was the most important event in the history of Ireland since the Act of Union of 1800, and for this reason the events leading up to it and the actions of those who played leading roles in it are of historical interest.

Eoin MacNeill was president and chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers, the organization that provided the main body of the rebels, although the role of James Connolly and the 200 men of his Citizen Army was of critical importance. MacNeill himself did not take part in the Rising and there has been much controversy about his actions in the events leading up to it.

It is now seventy-five years since the Rising of 1916, which led directly to the Black and Tan War. No one will ever know whether we might have loosened the British grip on Ireland by constitutional agitation, but we should bear in mind that the men of 1916, who invoked the ultimate appeal to arms, accepted that their efforts were likely to cost them their lives, and many of them did die. No man can do more for his country.

If there is an implied criticism in this biography of the 250,000 Irishmen who served with the Allies during World War I, it is not intended. These men, 50,000 of whom never returned, were as dedicated as the Volunteers who fought and died in 1916 to what they believed to be their duty to Ireland, and they deserve to be equally honoured.

O’Rahilly’s life would have had nothing of sufficient interest to justify a biography if it had not been for his part in the formation of the Irish Volunteers, and his death in Moore Street, leading a charge against a British barricade. There was an earlier biography by Marcus Bourke in 1967. The justification for a new one twenty-five years later is that many family papers have since come to light, which fill in details of O’Rahilly’s early life. Other important documents have also become available, especially the notes that he wrote from the GPO during Easter Week.

It would be impossible for me to write an objective biography of my father. I was eleven years old at the time of the Rising, and my father was to me then, and still is, the fountain of all knowledge, wisdom, courage, virtue and honour. If this is a biased view, it is relevant to mention that a French reporter who came to Dublin in 1917 to write about the Rising acclaimed O’Rahilly as ‘Le Bayard de 1916, sans peur et sans reproche’. (Bayard was a famous French knight ‘without fear and without blemish.’)

The book is dedicated to my mother, who had to endure many years of lonely widowhood after her husband’s death. It would never have been written without the encouragement of my wife, who urged me to persist in completing it when I had lost heart in the effort. I also wish to express my thanks to the publisher, Antony Farrell, and to his editor, Jonathan Williams, for their corrections and suggestions in an effort to make this biography readable.

Finally I want to acknowledge the help I received from Miss Emer O’Riordan, who did much valuable research for the book.

Aodogán O’Rahilly

Clondalkin, County Dublin

March 1991

1.The Background of the Clan

Ballylongford is a small town in County Kerry, on the south-west coast of Ireland. It is near the mouth of the River Shannon and has a harbour on the river, which was formerly used by small sailing vessels to discharge their cargoes for distribution in north Kerry and south Limerick. This harbour was an important commercial advantage for the town, before the railways were built linking Kerry to the ports of Cork and Limerick.

In such towns, in addition to the many small shops catering for the needs of the local people, there are often one or two larger ones that dominate the economic activity of the area, supplying hardware, building materials, fuel and drapery, as well as food and drink. Rahilly’s in Ballylongford was such a shop.

Richard Rahilly was the owner of this shop in 1875. He had inherited it from his mother about ten years earlier and had built it up into one of the largest of its kind in north Kerry; it did more trade than any similar shop in Listowel or Tralee.

Richard’s wife, whose maiden name was Ellen Mangan, had come from Gourbane in County Limerick. In 1875 they already had two daughters and Ellen was again pregnant. On 21 April in that year a son was born, and christened Michael Joseph after his paternal grandfather. It would have been a normal expectation that when this son grew up, he would inherit his family’s profitable business and further increase the substantial fortune that his father had amassed, ending his days as a well-respected and affluent member of the newly emerging Catholic bourgeoisie.

Any such expectations were not realized. Michael Rahilly, who became known as ‘The O’Rahilly’, was the prime mover in the formation of the Irish Volunteers in 1913, and was one of the leaders of the 1916 Rebellion. He was killed in the fighting near the General Post Office as he was leading his men against a British barricade.

There is today a plaque in Ballylongford commemorating its connection with the 1916 Rising, but the town had an earlier claim to fame. In 1900 it was prominently marked on a school atlas, published for Irish children by the British Ministry of Education. A footnote on this map explained that Ballylongford was the birthplace of Kitchener of Khartoum, the famous British military commander. He had achieved this fame when re-establishing Britain’s authority in the Sudan during the last decades of the century.

These two Ballylongford men died within weeks of each other. One was the supreme commander, in World War I, of the vast assembly of Britain’s armed forces, while the other was in effective command of the handful of Irish Volunteers in the GPO who were rebelling against the British occupation of their country.

Kitchener and O’Rahilly (the ‘O’ had been dropped during Penal times, but Michael restored it some years before 1916) were at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Kitchener’s family were Anglo-Irish and had come to Ireland where land was cheap after the Famine. Kitchener, like so many of the young men of Anglo-Irish families, had made a career for himself in the British armed forces.

The Rahillys were an Irish-Catholic family who had known hard times when the Penal Laws were enforced in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These laws debarred Irish Catholics from owning property or entering the professions. If an Irish Catholic owned a horse, any Protestant could take it from him by paying him £5, even though the horse might be worth many times this amount. The loss of a horse, when horses were the only means of transport or of cultivating the land, could be a crippling blow. However, in 1875, when Michael was born, the Rahillys were prosperous shopkeepers.

If it was usual for members of Anglo-Irish families to enlist in the British armed forces, it was by no means common for members of the emerging Catholic bourgeoisie to end up as revolutionary Irish nationalists. Most Irish Catholics were mild, constitutional nationalists, as were many Irish Protestants, but a sizeable minority of them had carved out comfortable niches for themselves in an Ireland governed by Britain. Such was the case with Michael Rahilly’s family. There was no trace in his upbringing of the convictions that were to lead to his death on the barricades. These may have begun when as a young boy he began to take an interest in his family background. Michael’s father came home one day and told the family that he had met an old woman in Tralee who told him that he was related to the Kerry poet Aodhagán Ó Rathaille. Michael set about investigating the connection. He discovered that there were many Rahilly and O’Rahilly families in Kerry. The name had acquired some distinction among Gaelgeoirí – enthusiasts for the revival of the Irish language – following the establishment of the Gaelic League in 1893. Michael then learned that Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, who was writing in Irish at the beginning of the eighteenth century (the same time as Dean Swift was writing in English), was one of Ireland’s greatest Gaelic poets.

The descent from one of the poet’s nephews to the family who settled in Ballylongford early in the nineteenth century is easily followed. An O’Rahilly, who was one of the poet’s great-grand-nephews, had been evicted from land near where the poet had lived, and had spent some years in Killarney before moving to Ballylongford where he had opened a shop. In the next generation, a son, also a Michael Joseph and the grandfather of the 1916 Michael Joseph, had married a Margaret McEllistrim about 1837. He died on 7 March 1849, the same year as the birth of his youngest son. His wife had borne him five children, three boys and two girls.

At the time of his death the Famine was devastating Ireland. It was a cruel time to be left a widow with five young children to support. People were dying of starvation and famine fever all over Ireland. Hundreds of thousands were leaving the country. Many of them had to sell everything they possessed to get the fare to board the ‘coffin ships’ out of Ireland, and many died on the voyage from starvation and disease. Within ten years the country’s population was reduced from 8.2 million to 6.6 million, whereas up to the Famine it had been expanding rapidly. There is no record of the cause of Michael Rahilly’s death, but he may have caught the famine fever like countless other victims.

Not only did Margaret Rahilly manage to bring her five children to maturity in good health, she succeeded in getting them well educated, thus giving them a good start in life. Her success in running the shop and educating her children suggests that she was a woman of strong character, but she could not have had any influence on her grandson, because she died in 1866 before he was born. Only two letters of hers have survived. In one, she is expressing her concern about a member of the family who is gravely ill. The other is written to Michael, her eldest son, who was then studying medicine. One of the subjects he required for his medical studies could not be provided in Cork and he had to attend lectures at the medical school in Dublin. She had not heard from him for a week when she wrote the following letter on 20 June 1858:

If nothing has happened to you why did you not write to me for the past week, knowing my anxiety?

Oh, for God’s sake write, or if anything prevents you get someone else to write and tell me all.

The most frightful things are occurring to me, may God of Heaven preserve me from trouble, for he knows that I have had my share of it already. If I don’t hear from you by some chance to-morrow, if I have sufficient strength of body or mind, I will be on my way to Dublin.

Or if there is more trouble in reserve for me, I hope, without harm to my soul, that the Almighty will take me before I live to see it.

Did you get the five pounds which Richard enclosed yesterday week? From your tortured mother

The five children were prolific letter-writers, and kept in touch with their mother wherever they were. Many of these letters have been preserved and throw some light on the family into which Michael Joseph was born in 1875.

Margaret Rahilly knew the importance of a good education for her children. Even though Catholic Emancipation had been achieved in 1829 and Catholics could own property and enter the professions, secondary and third-level education was still at an elementary stage of development. She needed energy and determination to provide the education she wanted her children to have and was able to run the shop so well that it could generate the funds to enable her to pay for this education. Her children would have been taught what were then called the ‘Three Rs’ (Reading, Writing and Arithmetic) in the local primary school. The eldest boy, Michael, was then sent to boarding school, first in Ennis and then in Killarney. In his first letter home from Killarney, in the early 1850s, he told his mother about the school routine and the sort of food they were given:

I now remember how anxious you are to hear all particulars so that I will now give you an account of how we are situated. Rising at 6 when prayers and a lecture from Challoney Mod read by Father Gaughton. Breakfast bread and milk 9 o’clock. School 9 till 1 at which hour dining. School resumes at 2 till past 4. Walking and exercise till 7, at which hour we have bread and milk for supper.

Prayers 8 and bed 9 o’clock.

Father Sullivan on last Sunday took us to the Chappie and showed us a certain seat formerly belonging to my family, which was at present unoccupied and desired me to go there on Sunday with whatever boys I wanted. It is in a rather dilapidated condition, but yet not very bad.

I had just finished the last sentence when the bell rang for breakfast, and I was surprised to get instead of milk TAY. The reason for it is I am sure that one of the boys got sick yesterday and I got a headache from taking milk. This one of the masters told us at dinner yesterday, so that I am sure that we will get tea for the future.

From this school Michael went to Queen’s College in Cork to study medicine.

There is no record of where the second boy, Richard, went to school. He was the father of the 1916 leader. A letter written in his late teens indicates that he was then helping his mother in the shop. Tom, the youngest boy, went to a seminary in Limerick to study for the priesthood, but soon found that he had no vocation and left that institution. He next comes to light in a letter to his brother Richard from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in August 1866. He was then seventeen years old, but there is nothing in the letter to indicate what he was doing in the United States or who was paying for his upkeep:

My dear old Dick,

I wrote you a kind of letter about 4 or 5 weeks ago, which I hope you got alright. I am just after getting up after last night’s fun. I had a jolly good night at the ball, lots of the handsomest girls I ever saw, but the worst of it was I am not able to dance, but they put it down to Ireland being such a wild place. Many’s the time I wished I had you with me here, and many’s the time I think over the great smokes we had together.

We will be going to the ‘Falls of Niagara’ soon and when we come back I intend to settle down. This is a great place for fun; every night I can go to a ball or boating or woodcock shooting, or, in fact, anything that I like to do. I’m entirely my own master NOW. Marlo tried to keep me down but he saw it was not good, so he gives me plenty of pocket money now. I am as happy as a king. …

I must go and take a glass of iced champagne to settle my stomach … very cheap every kind of drink is. … I see Jack Haid sailing down the river in his boat. … I wish he stayed away as I’m too ‘top heavy’ just now.

I’m just after dismissing him and I’ll give you a description of him. There he goes with the ‘helm’ in his hand, in his shirt and trousers, smoking a big cigar, with a jar at his feet and a negro fanning him, a regular fast fellow.

My dear fellow I am bothering you with this rigmarole of a letter. Goodbye. Excuse this shaky hand of mine. Ever your afft. and dearly attached

Tom

Tom never got over his addiction to alcohol, and on his deathbed confessed that there was not a day in his life that he did not have an irresistible craving for drink. It seems likely that Marlo was a friend or relation of the Rahilly family and that Tom had been sent out to him to learn a trade or business. If this was the purpose of his time in the US, nothing came of it. Eventually Tom returned to Ireland where he spent the rest of his life. He had a family of fourteen children, a number of whom became brilliant scholars.

The two girls of the family, Margaret and Marianna, when they had obtained whatever education was available in Ballylongford, were sent about 1850 to a convent school in France. The perfect French in which they wrote home indicates that they were several years there. Margaret wrote that she found it easier to write in French than in English, and signed her name as the French would write it phonetically, ‘Margaret Raleigh’. It is unlikely to have been common at that time, or indeed since, for girls of an Irish family, living in a small town, to be sent to school in France, although it is possible that the tradition of having to go to the Continent for education in Catholic schools was continued even after Catholic Emancipation.

Michael Rahilly was the first student of Queen’s College Cork to be conferred with a medical degree. He was interested in languages and, while studying for his medical examinations, was becoming proficient in German and Italian. After he had qualified as a doctor, he became a medical officer on board a British battleship. While he was waiting to board his vessel at Queenstown (now again called Cobh, its original name), he wrote home to his brother Richard asking to be sent ‘my favourite book, the History of the Rebellion of 1798’. The author was W.H. Maxwell and the copy he carried on the battleship was found among his grand-nephew’s books. It did not seem incongruous to him that the book he brought with him on the battleship conjured up visions of an Ireland free from British domination.

These foreign travels by Michael Joseph’s uncles and aunts meant that he grew up amongst close relatives who had lived abroad. His Uncle Michael had many tales of adventure in foreign lands on board the battleship. His Uncle Tom no doubt had tales to tell of how he had enjoyed himself in the United States. Both his aunts had lived for a number of years in France and spoke French fluently.

Thus, even if Michael Joseph grew up in a small town in Kerry, almost two hundred miles from Dublin, he heard stories of many other lands. However, when we look for evidence of radical Irish nationalism in his upbringing, the only trace of it was that request by one of his uncles to be sent his copy of Maxwell’s History of the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

Richard was the son who gradually took over the running of the shop, which he did successfully. As a young man, he wrote to his elder brother in Cork on 7 April 1858 about a new suit:

As I am at present divided whether I will get a new suit, I warn you to keep all old articles of yours for me in that line, as you can have the new and yours will do me beautifully.

The youth of eighteen who was willing to wear his brother’s cast-off clothing to save expense was not likely to dissipate the family fortune in extravagant living; nor did he. It would not be possible to amass a fortune just by being careful about spending money, but it helps. Catholics who were in a position to make money had one great advantage in building up a fortune. Since they were not received in the county set of ‘hunting, shooting and fishing people’, with the expensive entertaining that this socializing involved, they did not have to waste their money trying ‘to keep up with the Joneses’.

There is no record of what arrangements were made among the members of the family to enable Richard to end up owning and running the business, but it seems to have been an amicable one, and the Rahillys remained a closely united family. The family business that Richard Rahilly took over from his mother in 1866 was to expand greatly over the next thirty years. When it was advertised for sale, some years after Richard died in 1896, it was handling, in addition to the usual food and drink business, a large trade in coal, timber, steel and other building materials. An indication of the nature of the trade emerges from a letter that Nell, Richard’s eldest daughter, sent to her brother Michael while he was at boarding school at Clongowes. She told him that they had just discharged the largest vessel that had ever come into the port of Ballylongford, a sailing vessel carrying 200 tons of coal.

Before the railways were built, about the middle of the nineteenth century, small ports like Ballylongford were used for the discharge of cargoes of imported commodities, which then were moved by horse and cart to inland towns and villages. All this changed when railways were built to link the main ports to the inland towns. Large ships then discharged their cargoes into the railhead ports and these were sent by rail across the country. This put an end to the small ports, which did not have railheads and could discharge only small ships; but since there was no railway line to Ballylongford, the port continued to be used for the unloading of various commodities, which were then distributed to the surrounding area. The Rahilly shop also had the agency for the Ballantine flour mills of Limerick, and small steamers laden with this flour were discharged in Ballylongford for distribution from the Rahilly business.

Richard Rahilly had ideas for the development of his business. He realized how useful it would be for a shop if a machine were available for recording all cash sales. There were then no cash registers on the market, so he set about inventing one. A family story tells how a salesman from an English firm was shown the half-made cash register and was told how it was going to work. He went back to his company and told them what he had seen in this remote Irish town. The firm was in the engineering business and, realizing that there was a vast market for a such a machine, proceeded to design and manufacture one of their own. Richard spent £100 getting advice on the possibility of winning a legal action against the firm, but he was advised not to proceed with the case.

There was another development that Richard investigated thoroughly. The River Shannon at that time was one of the largest and most prolific salmon-fishing rivers in Europe. Shipping these salmon to the towns and cities of the British Isles would not have been possible before the completion of the railway network. But with the railways in operation it would have been possible to send salmon on the midday train from Listowel and they would arrive in London early the following morning. However, if the weather was hot, the fish would not arrive in good condition unless they were packed in ice.

The manufacture of artificial ice was then known to be technically feasible, although probably no plant was making it in Ireland. The process began with a boiler in which there was a roaring fire to generate steam. The steam was then used to operate a steam engine, which drove a compressor. A suitable gas, such as ammonia, was compressed and became hot. The hot compressed gas was then cooled by passing it through pipes chilled by water. When this compressed gas, now at atmospheric temperature, was allowed to expand, it became very cold and could be used to freeze water into ice.

Richard Rahilly saw an opportunity to ship salmon all over Ireland and Britain if he installed an artificial ice-making plant in Ballylongford. His wife, Ellen Mangan, was unhappy about the risks involved in making an investment of £20,000 and dissuaded him from going ahead. It was a substantial sum of money and would have been a serious loss to the family if the project had failed. Many years later, when the venture was being discussed at home, Michael Joseph said that he regretted that his father had not carried out the plan. He added wistfully that if the ice-making plant had been installed, he might never have left Ballylongford.

In addition to making money running his business, Richard Rahilly also discovered how money could be made on the stock exchange. During the years when he was building up his fortune, London was the financial capital of the world. People who had capital and the talent for anticipating commercial developments could find opportunities for making money by trading in stocks and shares and Richard Rahilly became competent at such trading.

One family tale recounts how Ellen and her daughters, Nell and Anna, came home from a shopping expedition to Limerick. Richard noticed that, instead of buying thread in hanks and then having to wind it on a piece of timber or paper to enable it to be used, they had been able to buy it ready wound on little wooden spools. He realized that the firm who made these spools, J&P Coats, would prosper, and so he bought shares in this company. Over the years these increased in value many times.

As Richard’s children, Nell, Anna and Michael, were growing up, they became aware that, in addition to the successful operation and expansion of his own business, their father was increasing his fortune with stock exchange investments. They also learnt about buying stocks and shares, but found out that there could be losses as well as profits from financial transactions. Anna told of the family’s dismay when they got word that the Munster Bank had failed in 1885. She did not say whether her father had held shares in the bank or if it was money on deposit, but the family knew it would be a serious loss for them. Richard was out sailing on the Shannon when the news reached Ballylongford. They could see his yacht becalmed on the river and dreaded the advent of a wind that would enable him to sail home because then they would have to break the news to him.

2.Family and School Influences

If Michael’s father, Richard Rahilly, had not been able to leave his son sufficiently well off to live comfortably without working, Michael could not have devoted the last years of his life to his efforts to get the British occupation forces out of Ireland. Yet although business interests were important in the Rahilly household, family members were by no means exclusively preoccupied with their business and financial investments. Richard Rahilly was actively involved in other matters. When he wanted a larger house, either in anticipation of his marriage, or shortly after it, he designed and built it himself. It was a three-storey house and is still one of the largest houses in Ballylongford. He enjoyed sailing and, when he wanted a small yacht for this hobby, he built one for himself. Michael Joseph grew up in a family in which there was a tradition of making the things you wanted, and this competence became one of his most notable characteristics.

Richard was also a member of Listowel Urban District Council: he attended meetings regularly, riding his bicycle the ten miles from Ballylongford to Listowel. In a letter to Michael while he was at school in Clongowes, his sister Nell said that her father had gone into Listowel to make arrangements for starting a cooperative creamery there. This creamery became the Kerry Co-op, now one of the largest business organizations in Ireland.

Another feature of the family atmosphere in which Michael Joseph grew up was his father’s interest in poetry. Anna told us how when he came on a poem that appealed to him, he would read it aloud to his family.

Michael’s family were deeply devoted to the Catholic religion. Every dogma was accepted without question, and every discipline imposed by the Church was faithfully observed. There was a family rosary every night and grace was said before and after meals. There was no possibility of Mass being missed on Sundays or on Church holy days, or that meat would be eaten on Fridays or on fast days. Michael’s sisters and his wife went to Mass and Holy Communion every morning all their lives, a practice they had acquired in their youth. The Rahilly family were in no way unusual in this commitment to the Catholic faith.

A love of music was an abiding interest among the members of the Rahilly family. In those days, if you wanted music and you lived in a small, remote town on the west coast of Ireland, you had to make it for yourself. Professor Alfred O’Rahilly recalled a visit he paid to Ballylongford in 1895, when his cousin Michael was away at medical school in Dublin. Michael’s father was obviously proud to be able to show Alfred a musical box that Michael had made. The father’s interest in music, and the educational importance he attached to it, emerges in the first letter he wrote to his son on 23 September 1890, when the boy had arrived at Clongowes Wood College in County Kildare in 1890: ‘About extras, you can say that I wish you to be taught piano and vocal singing for the present. If the banjo was taught I would not mind your going in for it.’

In the Rahilly house there was a piano, an organ and a violin, and all the children were interested in music. When one of Michael’s sisters wrote to him at school, after she had been to London, she said: ‘We bought a lovely bust of Beethoven yesterday which we will put on the piano.’

Michael never lost this love of music and singing. One of his companions in the political movement was Seán T. O’Kelly, who later became President of Ireland. When asked what he could remember about Michael O’Rahilly, he replied that if there was a piano in the room at any party, Michael would sit down at it and sing songs to his own accompaniment. The song that Seán T. remembered best was a music-hall song about a horse race in the Southern United States, ‘The Camptown Races’, which he heard Michael sing several times.

A cousin of Michael’s, a nun, was asked when she was over ninety what she could remember about him. She said that when she and her sister were at school in Eccles Street, Dublin, Michael had paid them a visit. There was a piano in the visitors’ room and he had sat at it and sung Mangan’s poem ‘Dark Rosaleen’. She said that, even after seventy years, she could still vividly recall how moved she had been, both by the words and the music, and the great feeling with which her cousin sang.

In an account that Michael’s sister Anna gave to the Military History Society, she said that shortly before Easter 1916 Michael paid his customary Sunday visit to their house in Northumberland Road. He had sat down at the piano and sung ‘Aghadoe’. When she recalled this after the Rising, she realized that it was in the nature of a swan song, which he was singing for them. She said that he had a lovely tenor voice.

This musical association also emerges in the poem that W.B. Yeats wrote about Michael O’Rahilly. Yeats wrote several poems about 1916 within a few months of the Rising, but twenty years later wrote one about Michael entitled ‘The O’Rahilly’. Three of the verses begin with a reference to singing. The first two verses begin with the line ‘Sing of the O’Rahilly’, while the last verse begins ‘What remains to sing about’.

Yeats may have associated Michael with singing as a result of a memory of a party they had both attended at which Michael had entertained them with his singing, but it could also have been from inquiries Yeats made of some notable characteristics of O’Rahilly. Michael hoped his children would also have this interest and talent for singing and he spent many hours giving us singing lessons, mostly Irish songs, while he played the tunes on the piano.

Another interest that Michael shared with his father, and never tired of, was handicrafts. As a boy, he had become familiar with woodworking from helping the local carpenter who was employed in the family business, and from this beginning he taught himself cabinet-making. There is a bookcase that he made in our house in Herbert Park that would be a credit to any cabinet-maker’s skill.

The first mechanically propelled motor car was made in the early 1890s and Michael got his first car in 1902. He never lost his interest in driving, overhauling and tuning cars, and devising new gadgets in the hope of improving their performance.

As far as is known, the Rahilly family were nationalists, but they were certainly not radical nor revolutionary. The only evidence of political interest during the nineteenth century is a collection book for the Repeal Movement, dated 1840. The Repeal Movement had been more or less active since Daniel O’Connell had won Catholic Emancipation in 1829. Many people believe that if O’Connell had campaigned for Repeal of the Union, instead of for Catholic Emancipation, he might have got the British out. He was in failing health when he won his first objective, and he died without making any progress in his efforts to get Repeal.

Irish political life was moribund for the next fifty years until Parnell infused new life into it about 1880. Then in 1890 Parnell’s liaison with a married woman, Mrs Katharine O’Shea, was used to destroy him politically. The tension and worry of the scandal led to his death the following year and created a bitter split in the Irish Party. When Michael was in his early twenties he was a committed Parnellite, but there is no evidence as to which side the family supported at the time of the split. In one letter from his father to Michael in Clongowes, he said that one of the girls would have gone to a meeting at which Parnell was expected to speak, but some domestic problem had prevented her. In another letter, the father wrote: ‘They expected to meet Patt Fitzgerald there to-day, as Patt, of course, with his usual aberration of intellect is a rabid Parnellite and must attend the meeting in Shanagolden.’

Regardless of whether the Rahilly family were pro- or anti-Parnell, there is no doubt that, in the eyes of Dublin Castle, the headquarters of the British administration in Ireland, they were typical of the emerging sensible, respectable, middle-class Catholic bourgeoisie whom the Castle were anxious to cultivate in their aim of achieving the anglicization of Ireland. It was in pursuit of such a policy that Richard Rahilly was made a Justice of the Peace about 1880.

The conferring of what was generally considered to be the ‘honour’ of being made a JP was an expression of confidence by Dublin Castle that the office-holder was someone who had no subversive feelings about the British occupation of Ireland. On the occasion of this honorary legal appointment, a number of local people gave Richard Rahilly a flattering testimonial.

The signatories of this testimonial included both Catholic and Protestant clergymen and four local JPs. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century the Rahilly family were truly part of the British establishment in Ireland. One brother was a JP, another an officer in the British navy and a third was now a clerk of the Petty Sessions – another Dublin Castle appointment.

Family letters show that there was an active interest in French among three generations of this Rahilly family. One of Richard’s sisters, Margaret Rahilly, who was sent to school in France in the mid 1850s, wrote home to her eldest brother: ‘Knowing how much you love the French language, I have decided to write to you in French.’ In the next generation, Nell, Michael’s sister, wrote a letter home in French from Mount Anville convent in Dublin. In another letter, in English, to her young brother, she said that she hoped that he was studying hard at his French, so they could have conversations in that language when she came home on holidays. Sighle O’Donoghue, a daughter of Nell Rahilly, has recalled how pleased she was when her American cousins came to live in Dublin, but said she could not speak to the youngest boy because he spoke only French. The result of this interest in French was that Michael Joseph grew up in a family in which many members spoke French and several had lived in France, and knew that there were other worlds beyond that of the English language and culture.

Having taken over the management of the family business in the mid-1860s Richard Rahilly worked hard, spent carefully and invested any surplus in quoted companies that seemed likely to develop. This enabled him to build up a fortune of at least a hundred thousand pounds, equal to millions of euro in today’s money.

There is no evidence that the Rahilly family was actively involved in politics, or even interested in them. In all the letters that have been preserved, the only allusion to the Irish language (even though most of the people in the area where they lived were Irish speakers in the middle of the nineteenth century) is a jocose reference in a letter home about 1860 from the eldest son, Michael, who went to study medicine in Cork. Michael said that he had lately met a boy called Sigerson (this was George Sigerson, who later became famous as a Gaelic scholar) who had urged him to study the Irish language because he was certain to do well at it. Michael commented that he would surely be at the head of the class since probably he would be the only one studying Irish! At that time the Rahilly children would have known Irish, but any idea that an Irish person had a Gaelic heritage worth preserving does not seem to have occurred to the boy who met Sigerson at Queen’s College Cork.

These uncles and aunts of the young Michael Joseph, with their tales of foreign travel, may well have stimulated a desire in him to travel abroad, although his parents were probably the most important influence in forming his character. Much is known about his father, Richard Rahilly, who was a successful small-town businessman, but there is nothing to suggest that Michael’s radical nationalism, which became a consuming passion, was influenced by his father.