4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

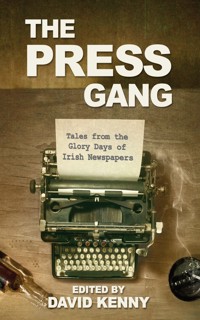

In September 1931, Pádraig Pearse's mother started a revolution in Dublin. She pushed a button, and the presses began rolling at Éamon de Valera's legendary Irish Press Newspaper Group, changing the landscape of Irish journalism forever. In The Press Gang, for the first time, fifty-five of its former writers and editors celebrate its glory days, from the 1950s to its closure in May 1995 - when the pub was the real office, and newspapers were full of insane, and insanely talented, people. There are stories of IRA gunmen in the front office, the reporter who broke his leg in two places (Mulligan's and the White Horse), Mary Kenny challenging the old boys' network, tea with Prince Charles, Johnny Rotten in a Dublin jail cell, and the hunt for Don Tidey. The Press Gang paints a poignant and hilarious pen-picture of an industry that has changed beyond recognition, and recalls an age of characters, chancers, geniuses, and above all, brilliant journalism.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE PRESS GANG

THE PRESS GANG

Tales from the Glory Days of Irish Newspapers

Edited by David Kenny

THE PRESS GANG: TALES FROM THE GLORY DAYS OF IRISH NEWSPAPERS

First published in 2015

by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © David Kenny. The individual essays are the copyright property of their respective writers. David Kenny and the contributors have asserted their moral rights.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-478-6

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-479-3

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-480-9

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright photographs. We would be grateful to be notified if any corrections should be incorporated into future reprints or editions of this work.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

In memory of Michael Carwood,

Contents

Foreword

Tim Pat Coogan

Editor’s Note

David Kenny

Country Edition – The Early Days

The reverend mother told me the fire wasn’t worth a fuck

Sean Purcell

From tea with Prince Charles, Bill and Hillary to hatch nineteen on Dole Street

Michael Keane

There’s a man in the front office with a gun

Michael O’Kane

How to be a rebel (and still know how to dye a rug)

Mary Kenny

Sometimes it does seem as though it were just yesterday

John Kelly

Adrian’s new book

Dick O’Riordan

Curtseys, spy stories, and the hack who mistook a teapot for a telephone

Maureen Browne

Big Daddy, and how I tried to save Johnny Rotten from jail

Paddy Clancy

New York cops in a time warp and IRA Armalites in coffins

Frank McDonald

Hot Metal, Poison Pricks, smoked haddock and the ‘lead’ story

John Brophy

The day I nearly killed Dev

Liam Flynn

Memories from the other side of the Stone

Harry Havelin

Who left that turd on the MD’s windowsill?

Seán Ó hÉalaí

Meeting Michael Hand – and how it changed my life

Éanna Brophy

President Kennedy’s copyboy (who missed the cut)

John Redmond

Hot metal and cold porter

Michael Morris

Boogie on Burgh Quay

Hugh McFadden

When we were the talk of the town

Patrick Madden

Racing Edition – The Middle Years

Garda six-packs, IRA six-guns and the hunt for Don Tidey

Don Lavery

An angry bishop, psychos, and a psychic theatre critic

Eoghan Corry

The last days of Dubliner’s Diary

Helen Quinn

From the Irish Crèche to Prime Time

David McCullagh

Drunk with Power

Brenda Power

Garvey

Patsy McGarry

Charlie and the Press factory

Lucille Redmond

Our eyes met across a crowded Dáil bar

Gerry O’Hare andAnne Cadwallader

Hey, kid, get into your car … and vamoose!

Ken Whelan

Our Lady of Fatima Mansions who was blessed by the Pope

Isabel Conway

Let sleeping subs lie (under the desk)

Fred Johnston

A blueshirt girl among the Northern media mafia

Mary Harte

Have change for the phone box, but don’t mention the wages

Ann Cahill

One minute we were safe as tethered goats…

Mary Moloney

City Final – The Last Days

Superquinn vouchers and a superhuman effort to save our bacon

Ronan Quinlan

The reporter who broke his leg in two places, and the ex-IRA man who outranked his English father-in-law

Ray Burke

Getting locked in the newsroom and sticking it to The Man

David Kenny

U2’s War story and Bob Dylan’s Battle of the Boyne

Denis McClean

Before the Fall

John Moran

Mná na Press

Kate Shanahan

Con Houlihan: when a giant walked the Earth

Liam Mackey

A brush with Brush Shields and a flower from the Diceman

Sarah O’Hara

Memories of my dad, and all that jazz

David Diebold

Bollickings are part of the job

Therese Caherty

In the front door and out the back

Louise Ní Chríodáín

The newspaper owner who took the piss. Literally.

Chris Dooley

Computer Ink

Fergal Kearns

Locking horns over Stagg over the gardaí

Richard Balls

The sound of news being written

Aileen O’Meara

Zarouk, Earthlings! Greetings from your old friend, Zodo

Sean Mannion

The News in Brief

Pansies don’t get the lead story: you have to have an eye for the ladies

Dermott Hayes

The haven of ‘chancers’ that gave me my novel approach to life

Muriel Bolger

How to keep the head down...

Tom Reddy

Sickness, it’s all in the mind

Des Nix

Ballet blues during Desert Storm

Maura O’Kiely

Rocke and rolling back the years

William Rocke

Foreword

Tim Pat Coogan

(Editor, Irish Press, 1968–1987)

Like a lot of national treasures, the Irish Press has disappeared into the bog of history. It literally was a very Irish institution and, in its day, a valuable one.

It was born out of the fertile brain of Éamon de Valera, who, having spent most of the period of the Black and Tan War in America propagandising, returned to Ireland to take command of the emerging peace negotiations some months before the war ended, leaving millions of dollars, subscribed by Irish emigrants to the Irish cause, lying in New York banks.

During the 1920s a New York court, unable to decide between de Valera and the Free State government, both of whom claimed the money, returned the bonds to the original subscribers. De Valera had seen to it that the subscribers’ names and addresses were kept on file. His lawyers had briefed him to expect the verdict, and he had letters prepared notifying the bondholders that he was founding a truly national newspaper. He included forms with this announcement that he invited the bondholders to fill in, deeding the bonds over to him so that he could use them as collateral to help found the Irish Press.

Many did so believing, like most of the early Irish Press staff who were employed by the paper when Padraig Pearse’s mother pressed the button to start the presses in 1931, that they were still working for ‘the cause’. The staff were mostly Republican, literate, loyal, and incredibly hard-working. It cannot be claimed that their loyalty was always rewarded by the paper’s controllers, for in reality the staff were working not for ‘the cause’ but for a segment of the de Valera family. De Valera passed the papers on to his eldest son, Vivion, who in turn entrusted them to his son, Éamon.

An episode that occurred while I was editor (1968–87) says much about the attitude of employers to those employed. Paddy Clare, who had been a Sinn Féiner, supporting Arthur Griffith, later mounted the barricades on the Republican side during the Civil War, and subsequently joined the Irish Press, which to him was a part of the vision of Ireland for which he had risked his life.

Somehow, during all his working years, Paddy was never made a member of the staff. He was paid on a docket and worked for decades on a graveyard shift from well before midnight until after 6 o’clock the following morning. Having retired on a not-very-generous pension, he came to me one day telling me that: ‘The lungs are bad and the doctor says I can’t take the winters here any more; I need to go to Spain. Trouble is, the pension won’t stretch. I need another fiver a week.’

Paddy never got the extra fiver. He died of emphysema.

Despite this, and many other stories of tight-fistedness toward staff that could be told, the Press Group had an extraordinary feeling of camaraderie about it. A great general manager, Jack Dempsey, helped to persuade the cautious de Valera senior (and Vivion) to add to the morning paper’s income stream by founding the Sunday Press in 1949, and the logical result of this growth process was the Evening Press, an extraordinarily successful venture, which began under the editorship of Douglas Gageby in 1954, when I joined the company.

For several years thereafter, the Irish Press Building on Burgh Quay, Daniel O’Connell’s Conciliation Hall, later the Tivoli Music Hall, was a place of youth, laughter, low pay and incredibly hard work. It was also the setting for some of the best journalism in the English-speaking world, motivated by something of ‘the cause’ feeling, although by now the ideals of 1916 were dimming, and in the Irish Press ‘the cause’ was represented by a dull, dutiful support of the machine politics of Fianna Fáil.

In fact, Fianna Fáil, and to a large extent the GAA, both owe a large proportion of their success to the Irish Press, which at the time went out of its way to promote their ideals. In the early 1930s the other papers regarded Fianna Fáil with marked hostility, and GAA games were hardly noticed by the Unionist Irish Times and the right-wing, business-oriented Irish Independent. But the obvious circulation gains of the Irish Press forced the other papers to follow its lead, from which the GAA benefited enormously.

The influence of the Press permeated Irish society in all sorts of unexpected ways. One of its many small columns read by devoted circles of niche readers was a historical snippet, ‘Window on the Past’, compiled by ‘S. J. L.’ S. J. L.’s son is today the highly respected author and financial journalist Pat Leahy, political editor of the Sunday Business Post, which in turn was founded by another Irish Press journalist, Damien Kiberd, whom I had the good fortune to hire.

One of those niche columns in the Irish Press nearly caused me serious grief. After internment was introduced in Northern Ireland in 1971, I wanted to see what conditions were like and had myself smuggled into Long Kesh under the assumed name of a prisoner’s relative. Just as the Hiace van containing the real relatives and me drew up at the prison, a man sitting opposite me said in a loud voice: ‘Hey, you’re the editor of the Irish Press, Tim Pat Coogan! I’m a coin collector and the Irish Press is the only paper that gives the numismatists [coin collectors] a show. Congratulations!’ Fortunately, the soldiers did not hear him.

Unfortunately, by 1968 the paper had become dull and unduly dutiful in its support of Fianna Fáil. Old, rural readers were dying, and no young city dwellers were being attracted to replace them. The diversion of resources to the Sunday Press and Evening Press from the flagship Irish Press meant that the paper was losing circulation at a rate of 20,000 copies a year. I was appointed with a promise that resources would be forthcoming both to stop the rot and to restore the paper to the position of influence it once held. For a time it did prove possible to halt the slide, even increasing the circulation.

However, at the same time, Vivion de Valera had embarked on an ambitious building programme that turned the Burgh Quay site into a version of the glass-covered Express Building in London’s Fleet Street, where Vivion had been sent to serve a brief newspaper internship.

Thereafter, working amidst the sound of builders’ drills and the sight of falling plaster, the spirit of the Tivoli rather than of Conciliation Hall permeated the place. I brought Harold Evans, the innovative editor of TheSunday Times,on a tour of the paper one evening, and the subeditors greeted us with a banner saying: ‘Welcome to Short Kesh’.

The building took forever to complete, but when it was finally finished, no increased flow of capital for the Irish Press ensued. The company at the time was one of the big property owners of Dublin, and money could have been found for investment in the paper, but this was anathema to the de Valera philosophy of control. No dilution of control by bringing fresh money into the coffers and fresh faces into the boardroom could be contemplated. It is not true as some wiseacres maintained that Dublin was over-supplied with newspapers. The Daily Mail and its Sunday paper were able to come into Dublin with deep pockets and show what could be done.

If Tony O’Reilly had not diverted large sums from the Independent Group to subsidise the London Independent and to purchase an evening newspaper, the Belfast Telegraph, for some €400m, in order both to bolster his claim to be the biggest press baron in Ireland and England and to secure a knighthood, that powerful group could also have been considerably wealthier. Even the solitary Irish Times somehow continues to breast the waves, as does the Irish Examiner.

However, suffice it to say that no life-sustaining outside influences were brought into the Irish Press. The company danced to the tune of a tone-deaf ceili band, while outside its walls Riverdance sounded. The awful industrial-relations climate got worse, not better. The Irish Press Group was the only one to suffer a closure when it introduced new technologies and dispensed with hot metal. After publication resumed, the Irish Press was not brought back until weeks after the other papers had hit the street – a clear indication of where priorities lay in the group, now headed by Vivion’s son. Moreover, when the Irish Press did resume, the manning agreement between the former printers and the management could not take the additional strain of the third paper, and there were many missed deadlines and lost sales.

A disastrous attempt to correct matters was made by turning the broadsheet Irish Press into a shoddy little tabloid. The size of the circulation soon resembled that of the paper.

Worse was to follow. A disastrous interlude of lawsuits and unpleasantness came in the wake of the catastrophic decision to bring Ralph Ingersoll into the management structure. Ingersoll’s father had been a great journalist, but he had made his reputation as an asset stripper of existing newspapers in the United States.

He brought his people with him, but they did not gel with the group’s traditions. There is a famous anecdote concerning an alleged passage of arms between one of his cost-cutters and the art editor who assigned photographers:

Art Editor: ‘We’re covering the climbing of Croagh Patrick next Sunday.’

Ingersoll representative: ‘Why? I’ve checked the papers and you covered that last year!’

The Ingersoll/IP experiment ended in tears and expensive lawsuits. The always-unfortunate relationship between the management and the staff suggested by the Paddy Clare anecdote persisted and accelerated throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and the paper closed its doors in the midst of an industrial dispute in 1995, never to reopen.

The last, fatal row could only have occurred in the Irish Press Group. Colm Rapple, the leading financial journalist with the Irish Press, took part in an Irish Times series on newspapers in which he did some straight talking about the situation facing the Press Group. The industrial-relations situation in the group at the time was akin to a building in which large amounts of petrol have been spilled. In this climate, the Press’s management fired Rapple for ‘disloyalty’. So much for freedom of speech. Predictably, the staff immediately ceased work. The upshot was that the paper closed its doors.

Newspapers are strange creations and attract strange people at managerial as well as at other levels. Vanity publishing costing hundreds of millions is not unique to Ireland, nor is the desire to retain control in the teeth of reality. The great general manager, Jack Dempsey, had not been followed by an outside replacement.

Dempsey had been succeeded by the loyal and patient Colm Traynor, who had formed a link with the great days of the paper’s birth. His father was Oscar Traynor, whose Fianna Fáil and Republican credentials were such that he was the Fianna Fáil minister chosen to bell the cat by informing the aging Éamon de Valera the first that it was time for him to retire as Taoiseach, which he duly did, and instead became president. Colm told me himself that he didn’t get on too well with ‘your man’, meaning Éamon, the grandson. However, as Colm began to grow disillusioned and lose patience with his situation, Éamon the lesser came to an unfortunate decision and an even more unfortunate choice. For some years the Sunday Press had been losing circulation. Éamon de Valera decided to remove the editor, Vincent Jennings, but to make of him the Jack Dempsey of the day. This happened in 1986. Many of the occurrences described above followed afterwards.

I left in 1987. By then the end was obviously near, and my advice on diversification and the bringing in of new expertise was unwelcome, or at least certainly unheeded. But I do remember the professionalism of my comrades over the decades with great affection, and in one or two areas with considerable pride. For some years after the Troubles erupted, the Irish Press coverage of Northern Ireland was amongst the best in the world. In 1976 the Press successfully campaigned against Conor Cruise O’Brien’s attempts to restrict press coverage by extending to the print media the provision of the Broadcasting Acts forbidding interviews with Sinn Féin spokespersons and inhibiting discussion of the ‘Northern issue’. Also, whether everyone would agree that it was an unmitigated blessing or not I don’t know, but I unwittingly helped to bring feminism to Ireland! That is to say, in 1968 I appointed Mary Kenny as woman’s editor. She did the rest with the people and the teams she drew around her.

I also remember with respect the author and Evening Press features editor Sean McCann, who one day in 1968 introduced me to David Marcus, who wanted to extend his career as an editor of literary magazines by devoting a full page in a national newspaper to new Irish writing each week. I thought the idea a brilliant one, and as a result, for twenty years, almost every Irish writer or poet of consequence had their first or subsequent writings published in the paper. I’d like to think that Sean’s son, Colm, the novelist, forms part of that tradition.

Two colleagues who I cannot conclude without mentioning were Fintan Faulkner and John Garvey, both of whom worked with me as deputy editors. I could not have asked for more loyal or professional men at my elbow.

The end of the Irish Press was sad, recalling words spoken after the Battle of the Boyne: ‘Change kings and we’ll fight you again,’ but in its day it made a real and valuable contribution to Irish life.

Editor’s Note

David Kenny

A day may be a long time in politics, but it’s an eternity in the newspaper business. What was influential, entertaining, annoying and – above all – newsworthy at breakfast, is cat litter by supper time. The print industry is built on immediacy, where hour by hour each edition makes its predecessor redundant and irrelevant.

The memory of each edition fades, but the memory of the title remains. This is the case with the legendary Irish Press Group. It is twenty years since its demise, but its readers still remember it. So do its employees. Many of those who worked for it are still active and thriving in the business, having learned their craft in the most inventive newspaper group this country (or any country) has ever produced. The Press’s influence lives on.

The group (Sunday, Irish and Evening) constantly floundered, and those half-drowned souls who manned the pumps did so because they loved it. Financial reward never came into the equation; to work for the Press meant being constantly broke. The rewards for being a journo are not tangible, and in the case of the Press they are only memories now. Memories of stories broken, deadlines met, mad characters sidestepped, bizarre work practices and monstrous hangovers. Memories of an age when a pen, a notebook and a public payphone were the laptops and Google of their day.

So why bother celebrating a failed business after all these years? The answer is that the Press was never a business to its readers or writers: it was a way of life. That way of life and news dissemination has vanished like the Linotype. In terms of influence, a single tweet can replace an entire day’s labour by a footsore hack. This book is a collective memoir by sixty former papermen/women that aims to give an insight into the golden (or at least, pyrite-hued) pre-Twitter/internet age of newspapers. It shows how news was published the hard way: with boots on the ground and, occasionally, faces on the ground too, generally under a bar stool.

It started with a tentative post on the Irish Press journalists’ Facebook page. ‘I want to do a memoir,’ I typed (hesitantly). ‘Anyone interested in writing a piece?’

My brief was simple: write what you remember, and at all times be entertaining. And this book is entertaining, for anyone who has ever picked up, thrown down or cleaned themselves intimately with a newspaper. It was never intended to be just a dry academic tome for journalism students – although I humbly suggest that it should be required reading.

That said, there will be critics who will point out omissions. There are some household names missing, and I would have liked to have had more sport. Some former writers had put the past to bed and were unwilling or unable to document their experiences. This was a voluntary enterprise by its contributors; I could only gently cajole people and hope that most were aware of the project’s existence. I couldn’t contact all of the 600 ‘Pressers’ who worked there in May 1995. If I had – and they had all agreed to write a piece – then this book would never have fitted through the door of your downstairs loo. Besides, many of them are dead.

I decided from the start that I would take a ‘light-touch’ sub-editing approach to this book. A number of strong personalities (Tim Pat Coogan, Gerry O’Hare, Dermot McIntyre, etc.) crop up in many of the stories. Descriptions, situations and work practices do too. I believe their reappearance creates its own narrative sub-thread. Each chapter stands alone and is deeply personal to its author. As editor, I didn’t want to impose my own voice on my colleagues’ work; they are old enough and skilled enough to tell their own stories without interference.

The book has a rough chronology, starting in the 1950s and ending in the 1990s. It is not intended to be read from beginning to end. My best advice is to dip in and out, like you would with a newspaper.

Monumental thanks and a rousing ‘knockdown’ go to Patrick Madden for assembling the main body of the picture sections. And a subeditor’s salute goes to photographers Ronan Quinlan, Austin Finn (RIP) and his family, Cyril Byrne, Pat Cashman, Colman Doyle, Brian Barron, Colin O’Riordain, Brenda Fitzsimons, Colm Mahady, Bryan O’Brien, Seán Larkin, Tom Hanahoe, Russell Banks, Bob Hobby, Gary Barton, Tony Gavin, Mick Slevin and Niall McInerney.

Finally, I’m eternally grateful to Justin Corfield, Edwin Higel, Dan Bolger, Shauna Daly, Mariel Deegan and all at New Island for immediately seeing the merits of this unique project. I am proud to note that this is the first book of its kind printed in any language, anywhere.

Another ‘scoop’ for the Press gang.

David Kenny

September 2015

Country Edition

The reverend mother told me the fire wasn’t worth a fuck

Sean Purcell

(Chief Subeditor, Irish Press, 1995)

Even by the standard of the bizarre vagaries of life at the Irish Press, the editor’s complaint that evening was a bit unusual. One of our subeditors had poked his penis through the letterbox and pissed all over the floor of his office.

There was nothing salacious about how he had identified the culprit from inside the room; he had simply guessed his identity having encountered him showing signs of volatility earlier. About the affront itself he was uncharacteristically sanguine, leaving it to me to contain the fallout. It set me wondering how I had ended up in a madhouse, appropriately enough a converted music hall on the Dublin quays. The building we occupied had been the old Tivoli Theatre, and before that the Lyric. Only now does it strike me: our destiny had been linked from birth with laughter along the Liffey.

I had started out in Waterford, in a dilapidated building, also on the quays, a sixteen-year-old graduate of the tech in Mooncoin earning seven shillings and sixpence a week as a cub reporter with the Star. Within months, and long before the term had been coined, I was headhunted by Smokey Joe Walsh, owner/editor of the Munster Express. Shamefully, I deserted the Star for an extra half crown. Two years later I went to Roscommon, to the Champion, and in another two years I was with the Sunday Independent in Dublin. Communications colleges and media studies belonged to the future. The route I took was a common way of qualifying as a journalist in the fifties and sixties: one learned the rudiments of local government in the council chamber and the workings of the justice system in the courtroom. It was an apprenticeship that left one short on theory but sound in practice.

I must have been ludicrously cocksure back then because when McLuhan drew attention to the speed at which communications were shrinking the world, I thought he was a bit tardy with the news. Hadn’t the Skibbereen Eagle been keeping an eye on Russia the year before my father was born? The global village genius was on to something, however, because in the course of my career print journalism dashed, in a decade, from hot metal through new technology to the dubious delights of social media. (Try whistling that to the tune of John Adams’s Short Ride in a Fast Machine.)

I arrived at the Press with fifteen years’ experience in the newsroom at RTÉ, a career move I had made for personal reasons, as the saying goes.

The Press in the sixties and seventies had been through a mini golden age of women’s lib, but that was well and truly over by the time I got there. The campaign for condoms had been shouldered aside by a campaign for cordite. That, certainly, was what Conor Cruise O’Brien suspected as he kept a daily tally of our pro-Provo letters in his ministerial office. Undeniably, our political hue had intensified from grass green to effulgent emerald.

No woman found employment on the subs’ desk for quite a bit of my time there, and it was late in the seventies before we even considered it odd that we worked in a woman-free zone. There was a vague feeling – lame excuse, more accurately – that their tender souls would not survive the deadly mix of ungodly hours, blue air, coarse cynicism and a whole deskload of testosterone. Vincent Doyle of the Irish Independent was the last morning paper editor in Dublin to concede defeat on the exclusion of women subs, and he did so with considerable reluctance and an indelicate proviso: ‘So long as you treat her like the rest of them and work her bollocks off,’ he instructed his chief sub.

In those days a warlike rivalry existed among the three Dublin papers, and was fiercest between the Press and the Independent. TheIrish Times, then as now, maintained a prissy distance between itself and its noisy neighbours. Amazingly, the Cold War ended every night at midnight when a so-called night-town reporter took over on the newsdesks. Those fellows collaborated freely on stories breaking in the small hours, and if things grew hectic they shared the workload between them.

Maurice Liston, a Press man who went on to become a chief reporter and the terror of the newsroom, was collaborating one night with the Independent’s night-town man when news broke of two serious-sounding accidents: a fatal car crash and a fire in a convent. The Indo’s man was the first to deliver. He phoned across a substantial accident report to Burgh Quay and then enquired if there was any news from the nuns. Liston’s response has become part of newspaper folklore. ‘I got the reverend mother out of bed,’ he said, ‘and she told me that fire wasn’t worth a fuck.’

Print workers practised an ancient rite called a knockdown to mark occasions such as staff retirements or sudden windfalls of good fortune. It involved a caseroom assembly creating the loudest noise possible by banging metal tools on their metal benches. The din reverberated throughout the house and was kept up for several minutes. Major Vivion de Valera, the managing director and founder’s son, was once accorded a knockdown after the staff had received an unexpected bonus. Unfortunately, he misdiagnosed goodwill for hostility and was terrorised by the clangour. Given his military credentials – he had four years’ service on the side of Republican neutrality during the wartime ‘emergency’ – he might have been expected to face the danger with resolve. Dispatches, however, record that discretion trumped valour. The major ran away. He found shelter in an editorial office, complaining that the staff upstairs had gone completely mad. The celebratory significance of the knockdown had to be spelled out.

In an earlier incident involving the major in the caseroom, he went to sympathise with a man whose shoe was coming asunder, the sole slapping noisily on the floor as he walked. ‘Ah sure,’ said the wretch, ‘I can barely keep body and soul together with the money you are paying us.’

‘I may be able to help you there,’ said the major, and the man watched with eager anticipation as he went deep into one of his pockets and came up with a stout rubber band.

Breandán Ó hEithir swore to the truth of that when he told it to me during our time in RTÉ. Ó hEithir had played a leading role in another incident involving the major. De Valera had returned from lunch one day to find a large human turd sitting on a windowsill inside his office. Who could the perpetrator be, and what was his motive? A discreet inquiry was launched by the major and his inner circle, but after a fortnight of delicate probing they were no nearer to the truth. Enter Ó hEithir in an imaginary deerstalker. Had the window been open or closed? Frequently open in daytime, he was told. The boy from Aran had the answer in a flash. ‘Go back,’ he advised, ‘and tell the major the matter was carried up from the Liffey by a gull, and the gobshite was interrupted before he had time to have lunch.’

Mulligan’s of Poolbeg Street was our pub of choice. There were those who fancied Kennedy’s at Butt Bridge, but the atmosphere was so sedate there I usually avoided it, fearing I might hear a decade of the rosary from behind the counter. The printers, taking a break on official ‘cutline’ or unofficial ‘slippiers’, favoured the White Horse, a hostelry to which Benedict Kiely had given a wide and shady reputation with his story ‘A Ball of Malt and Madame Butterfly’. Its renown was strictly local, though, no match for the notoriety of its New York namesake, the place that literary drunks will always associate with Dylan Thomas’s last, fatal binge.

Some nights got stretched, like ourselves, and we moved with the hard chaws from Mulligan’s to the Irish Times Club. That was a dingy drinking den three floors above a bookie’s shop in Fleet Street. The drill for entry was a secret of its doyens. One pressed a bell-push in a nondescript door and a window was opened on the top floor. A head poked through and you moved out of the shadows and presented yourself in the light from a street lamp to be identified and assessed for fitness for admittance. If you passed muster, the door-key came down in a matchbox. Sober, you caught it in mid-air. Half cut, you went looking for it in the gutter. Either way, this was open sesame, and you ascended half a dozen flights to nirvana in the clouds. In truth, the place resembled an upstairs cellar.

The barman I knew only as Charlie. He was a veteran curmudgeon whose moods veered between glum and grumpy. One was advised to indulge him because he enjoyed supreme authority in deciding whether you were served or barred. I recall two merry punters giving him an order for two pints of Guinness and two gin and tonics. He took the order without demur and returned five minutes later with the pints. ‘And now, gentlemen, you have two minutes to get the floozies off the premises,’ he told them. He had surmised, correctly, that the gins were intended for two women they had hiding on the landing.

At the club one rubbed shoulders mainly with other journalists and printers, and occasionally a guard or two coming off duty in the nearby Pearse Street Station. Now and again the place provided more exalted company. I woke up one night and discovered that the sonorous monologue I’d been half hearing while I dozed was being delivered, to a fawning audience of machine hall dungarees, by Peter Ustinov, sometime actor and unceasing raconteur. It was Thursday night/Friday morning, and the overlarded old windbag was rehearsing a Late Late Show appearance. Or maybe it was Friday night/Saturday morning and he was basking in the afterglow. It turned out he had been touring the louche side of Dublin life, and his chaperone, some personage from TheIrish Times, had condescended to take him to the club, a place in which he himself would not normally be seen, alive or dead.

Around midnight our newsroom could go weirdly quiet as shifts ended and staff drifted away. The last copy had been sent for setting and the final page proofs were being passed down to us to be checked. The rasp of our deputy editor, John Garvey, was suddenly silent; he had retired to his room with a couple of page proofs and a fine moral comb. Garvey, an earnest and quaintly strait-laced journalist, harboured a hidden fear that some smart alec would one day slip a sexual innuendo past him in copy. I used to think he’d find a double entendre in the Lord’s Prayer. John Banville, the chief subeditor, and at the time engaged in real life with his early experimental novels, assumed the stillness of a Buddha and sank, luxuriously one imagined, into the labyrinthine sentences of a Henry James hardback. Jack Jones, the night editor, had entered a spell of intensive combat with TheFinancial Times’s cryptic crossword.

A musical soundtrack for this tableau was provided by John Brophy, a subeditor and occasional music critic who worked late shifts by choice. Sometimes it was a lively tin-whistle jig, more often a plaintive nocturne on his flute. Brophy has a head crammed with the kind of esoteric information useful to no one but a sub. The word on the desk was that to ask him for the time was to risk getting a history of the cuckoo clock. Offered a read of someone else’s IrishTimes, he turned it down with the observation that life was too short. We fancied ourselves for our rigorous way with verbose reporters, and that oblique comment can be seen as Brophy’s two fingers to prolixity at TheTimes.

Down in the reporters’ area, close to the big window that overlooked the Liffey, Frank Duignan, a former Galway footballer and like myself a refugee from RTÉ – the Irish-language Nuacht desk in his case – helped himself to generous tipples from a bottle of whiskey he kept locked in his drawer. Frank, or Proinsias, must not be knocked; there was a night in 1981 when he, working alone and against the clock in the early hours of St Valentine’s Day, turned in an exemplary first account of the Stardust disaster.

In that quiet hiatus around midnight I once noticed a boozy fellow wake up in panic on the sports desk. He had just realised that he was not going to make the lavatory in time. He swayed out of the room, dropping here and there the sort of solid samples of which his doctor would have been proud. (Me too. Boxer shorts or nothing, one supposes.) A sports desk copyboy, working well beyond the line of duty, scurried in his wake and, with a pooper-scooper hastily fashioned from an old Evening Press, removed every vestige of offending matter. Passing through our area, he gave me a complicitous wink, and implicated me in a conspiracy of silence that has endured for almost forty years.

Younger readers should know of the indignities that attended our demise. The major had gone to a final knockdown in the sky, and de Valera mark III, a.k.a Major Minor, had assumed control with the title of editor-in-chief. In a fit of financial desperation, and with Vincent Jennings, editor of the Sunday paper, as his best man, he had climbed into bed with an American carpetbagger in what he described as a marriage made in heaven. It turned out to be a disaster made in hell. In preparation for the Irish–American nuptials, de Valera and Jennings had started to shrink the kids. The Irish Press, the firstborn and the flagship, was reduced to a tabloid. And then, after a fractious cohabitation and the goriest of divorce proceedings, plus a couple of years of unrelieved gloom, all three papers were gone. There would be no more laughter on Burgh Quay.

The final meltdown. Just seeing the words reminds me that in our hot-metal heyday we had a man upstairs called Gary, and he lived in a permanent lather of sweat. He worked in the foundry, melting down used metal for recycling and fetching on a bogey the pages of type the compositors had locked together in chases and which in his domain would be converted into flongs for the presses. (Notice how quickly even the words of our era are falling through the sieve of history.) We knew Gary as the bogeyman. The caseroom fellows, who revelled in creative christenings, called him the Incredible Melting Man.

Rumours used to reach us in those days of strange goings-on among our colleagues on the evening paper. They occupied the same desks as us, but during daylight. There was an old man there who always took his bicycle to work, by which I mean all the way upstairs to his desk. In quiet moments between subbing stints he liked to work on this machine, and in the year of his retirement he became fixated on fitting it with a sail. When eventually he achieved a satisfactory marriage of cloth and iron he brought his strange contraption to ground level, where, following adjustments in Poolbeg Street for wind conditions, he was last seen passing east under the Loop Bridge. With a fresh sou’wester behind him, and a few startled motorists in his wake, he was scudding, like a clipper, towards the harbour.

The past, as the man said, is another country.

From tea with Prince Charles, Bill and Hillary to hatch nineteen on Dole Street

Michael Keane

(Copyboy/Reporter/Northern Ireland News Editor/Editor, Sunday Press, 1965–1995)

Maurice Liston was a big man in stature and in reputation. He was the doyen of the national media agriculture correspondents, a very important role as agriculture was the only real driver of the Irish economy in the sixties and early seventies.

Once, attending the Thurles Agricultural Show, a major event in the world of agriculture, Maurice was sitting in the press tent waiting for the show committee to deliver to him the day’s results, champion heifer, prize bull etc. A young reporter from the Tipperary Star sat alongside Maurice and, awestruck at being in the presence of the great man, enquired politely: ‘Mr Liston, what’s it like working in the Irish Press?’

Maurice put down his generous glass of Jameson (without which no self-respecting agriculture correspondent could operate) and replied: ‘Son, the Irish Press is like a three-ring circus. And I would be like a trapeze artist in that circus, going swing, swong, swing, swong. And there is always some bastard there to grease the bar.’

Despite Maurice’s jaundiced view of the Press, it is extraordinary that some twenty years after its closure, and despite the bitterness that surrounded its last days, the well of fond memories and endearment that is evident amongst those who worked there for their days in Burgh Quay still persists. When ex-Press people meet for any convivial occasion, and sadly they are rare enough these days, stories soon tumble from their lips – hilarious stories about the most bizarre happenings in Burgh Quay, but also in the nearby hostelries such as Mulligan’s, the Silver Swan, the White Horse, the Scotch House, and on assignments far and wide.

The wonderful characters, the messers, the occasional weirdo, the drunks, the religious fanatics, the rabid Republicans, the anti-Republicans, the right-wingers, the left-wingers, the misers, the geniuses, the superb craftsmen and women, the chancers, the workaholics, the dossers, the brilliant reporters, the superb layout men, the astute subs, the outstanding writers, the reporters who could get a story but who couldn’t write English, the wonderful shorthand writers who could take dictation in both English and Irish, the speedy copy-takers, the parties, the drinking, the rows, the romances, the craic – all of these will get an airing when the meetings occur over a few pints or glasses of wine.

One thing that transcended the often chaotic nature of life in Burgh Quay was great journalism. The Press newspapers had, and still have, a reputation for producing some of the outstanding journalists and journalism in Irish media history, with its reporters and photographers rated at the top of their respective fields.

When I joined the Irish Press Group as a copyboy/trainee journalist in 1965, the Sunday Press was the biggest selling of the Sunday papers, the Evening Press was coming into a golden age when it came close to outselling the Irish Independent, and the Irish Press was about to experience a renaissance with some brilliant journalism. It was, therefore, a very exciting time to be embarking on a career in journalism. I was allocated to the newsdesk as diary clerk, and my job was to ensure that a record was kept of all forthcoming events such as Dáil and court sittings, inquests, tribunals, festivals, courts martial, official openings, commemorations, press conferences, presidential comings and goings, etc.

It was also my job to ensure that country correspondents were covering events for the papers, so very quickly towns around the country became known by the names of the correspondents that sent stories from them. Thus, it became Maddock Rosslare, Hemmings Crolly, Joseph Mary Mooney Drumshambo, Molloy Ballina, McEntee Cavan, Gillespie Castlebar and so on, because that is how they announced themselves to the copy-takers. Two of the outstanding ones were Áine Hurley and Olive Dunne, who were brilliant at taking down long and long-winded reports from correspondents who were paid by the word.

Our staff man in Waterford in those days, John Scarry, rang through one morning with a story about the city being hit the night before by Hurricane Áine. Mick O’Toole, the Evening Press news editor, got the story and enquired: ‘John, who christened it “Hurricane Áine”?’ to which John confessed: ‘I did, I named it after Áine the copy-taker!’

The same John rarely came to Dublin, but on one occasion he was cajoled by the chief news editor, Mick O’Kane, to join him in the city for lunch. The following day the redoubtable Betty Hooks, then the diary clerk, and one of the ‘stars’ of the newsroom, asked him how his lunch with the boss had gone.

‘Ack, it was useless, aetin’ raw mate in a cellar,’ was his verdict on Dublin’s finest medium-rare sirloin steak.

Drink played a huge role in the life of the Press in the days before a mid-seventies’ house agreement brought much better wages and a higher standard of living for all concerned. Before that, however, the ‘free drink’ was particularly welcome, and especially welcome to some was an assignment that involved nuns who might be opening a school or a hospital extension. At the inevitable reception after the formalities, the whiskey bottle came out and, as ‘Little Ed’ McDonald, a veteran snapper, told me, you got to experience the ‘Reverend Mother’s pour’ because nuns poured whiskey as if it were red lemonade!

So you can imagine that the annual arrival of Good Friday was not something to be relished by the thirsty newsmen. The accommodating O’Connells, who ran the White Horse, did a brisk trade in their upstairs lounge, however. The doors below were locked, of course, so that unwelcome guests would not intrude. On one such Good Friday, as the boys were enjoying their pints and small ones, who should come into the newsroom but the Man in the Mac, Major Vivion de Valera, TD, controlling and managing director AND editor-in-chief.

‘Where is everybody, Mr Hennessy?’ he enquired of the man holding the fort in the newsroom, Mick Hennessy. ‘Oh, they’re all out on jobs, major,’ lied Hennessy. The major flounced off, not a bit convinced. Mick quickly slid out of a side door, but could get no response from upstairs in the lounge. There was nothing for it but to climb up a drainpipe to knock on the window and warn the lads. Just as he reached the top he heard the dreaded voice of the major from below: ‘Is this where the jobs are, Mr Hennessy?’

Meanwhile, back to the newsdesk. Each morning a list of what was on that day was handed to the chief news editor, who allocated jobs to reporters. A lengthy news list had to be prepared for the Irish Press editorial secretary, Maureen Craddock, to type up for the evening editorial conference, when the contents of the following day’s paper would be discussed and decided upon.

Working as a diary clerk was wonderful training because you got to know how the system worked in detail, but in my case it went on for a year and a half, about a year longer than I thought necessary. I couldn’t wait to be made a junior reporter and join the exciting team. Once I became a reporter I was like a bird freed from captivity, and a great adventure began that only ended thirty years later. That adventure took me to every part of Ireland and also to the UK, Germany, Italy, the Soviet Union, the United States, Israel, Lebanon, Norway, Holland, France, and perhaps most importantly to Northern Ireland, where I was Northern news editor for five years.

My role as a reporter meant work five days a week. It could be ‘day-town’ for the Evening Press starting at 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. if you were one of the elite Evening Press team, 10 a.m. if you were on duty for both the Evening Press and the Irish Press. On that shift you could end up in the courts or chasing fire brigades around town on a breaking story. The 3–11 p.m. shift was for Irish Press duty solely while ‘night-town’ was the graveyard shift, usually occupied by one-time Éamon de Valera minder and character Paddy Clare (‘I carried Vivion de Valera on my shoulders to hear his daddy speak at a rally in O’Connell Street one time; he’s been carrying me ever since!’)

Each week one reporter was allocated Sunday Press duty. This involved joining a photographer on a three-day trip to some part of the country to suss out what we called the ‘two-headed donkey’ stories – in other words, unusual, entertaining local stories that would appeal to the wide readership of the paper. It was fun and somewhat pressurised as you had to come back with a few picture stories as the leads handed out by the Sunday Press news editor, Gerry Fox, were usually thrown out of the window at Newland’s Cross. On one occasion the photographer was ordered to stop the car in a small hamlet in Co. Clare, the reporter hopped out, walked away and was never seen in Burgh Quay again.

The newsroom was a very noisy place, what with the constant clatter of typewriters being thumped at high speed by reporters racing to meet a deadline, news editors screaming instructions or demanding copy, phones ringing … in other words, controlled bedlam.

On one occasion, late, lamented colleague Sean MacConnell was trying to get information from the postmistress of an outpost in deepest Mayo about a local girl who had been knocked down and killed crossing a street in Paris. The line was so bad we all had to stop typing so he could hear. The postmistress gave out the required information: ‘She went to the local national school, played camogie for the local club, a Child of Mary, a lovely girl, from a respected farming family; the funeral is on Thursday next.’

Finishing up, Sean shouted down the line: ‘So they are bringing her home then?’

Postmistress: ‘Oh yeah, sure she had a return ticket!’

The newsroom mayhem could be interrupted by the sight of rampaging caricaturist Bobby Pike, a repentant Mick Barber on his knees before an embarrassed news editor, George Kerr begging forgiveness for being two hours late back from a job, calls from the front office where Brendan Behan was slumped in his special chair demanding money for an article that had not yet been published, or the signal that a major disaster had happened, which sent the whole place into frantic overdrive.

The competitive battle with the Irish Independent, in particular, was intense. It was Munster v Leinster in present day intensity. We strove might and main to ensure that we got the big stories and got them first. TheIrish Times seemed to be happy as long as it appeared, never mind that it was a day late.

The excitement of the big story was matched only by the satisfaction of beating the Indo hollow or getting a major scoop on our rivals. Some big stories didn’t work out as planned, however, and it had nothing to do with the Indo. That was the night we buried Robert Kennedy prematurely in the Sunday Press. The phones went mad the next day with readers complaining, and one was somewhat mollified when I chanced my arm by asking him if he had never heard of the time difference. I only got away with that one once.

I had joined the Evening Press team in the late 1960s, and was being sent to cover the North on a periodic basis, which was harrowing enough. And then in 1972 Mick O’Kane asked me if I would take up the role of Northern news editor based full-time in Belfast. It was a difficult decision, but I agreed on condition that every second weekend I would leave for a break and would only disrupt my weekend if I decided to do so. It was the only way to manage the stress and maintain some sort of normal life with family and friends.

Going there in November 1972 to take up the position in succession to Vincent Browne, I was joined by a popular Scottish reporter, Laurie Kilday, who had been asked at his interview if he was willing to report from Northern Ireland if appointed. Little did he know that within a few months he would be sent up there full-time.

I will not dwell here on the difficulties and dangers of reporting on some of the worst violence during the awful Troubles. They have been well documented. What is perhaps not appreciated so much is that the people of Northern Ireland, even in their darkest hours, have a black sense of humour.

Laurie was caught one day in the middle of a riot involving Falls Road youngsters and the British Army, and took shelter in a doorway as the battle raged up and down the road in front of him. Only then did he notice a little old lady standing in the doorway beside him, shopping bag in hand.

‘The bastards are not fightin’ fair – they have shields and helmets and ambulances and everything. Our fellas have nothing,’ she observed to Laurie.

Laurie gave a terrified ‘Aye’ in response.

The old lady realised that the ‘Aye’ was not from her part of the world, and asked: ‘Where are you from, son?’ to which Laurie replied: ‘The Gorbals in Glasgow.’

The Gorbals was one of the toughest housing slums in Europe at the time. The old lady responded: ‘The Gorbals? In Glasgow? God, I’d hate to live there. I believe it’s fierce wild,’ not a bit bothered by the mayhem around her.

On my return from Belfast in February 1978, I was appointed assistant editor of TheIrish Press working with Tim Pat Coogan, John Garvey, Michael Wolsey and the chief subeditor, John Banville. It was a totally different type of job, producing the paper, writing editorials, editing letters etc. I badly missed the cut and thrust of the newsroom, the buzz of chasing the great stories of the day. So when a job came up as deputy chief news editor under Mick O’Kane, I went for it, and my life took off once again. It was like having a new career.

The newsdesk is the control centre of the news-gathering operation, and when a big story breaks there is nothing better than the excitement it generates. It was the time of ‘Gubu’, the era of the three elections, the Haughey heaves, the Pope’s visit, President Reagan’s visit, and of course the continuing Troubles in Northern Ireland – a wonderful time to be a journalist.

From there I went to the Sunday Press as deputy editor and news editor, which was demanding but very interesting, and I worked with some excellent journalists. Just a year and a half later I succeeded Vincent Jennings as editor, and filled that role for eight years until the house of cards came tumbling down.