Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

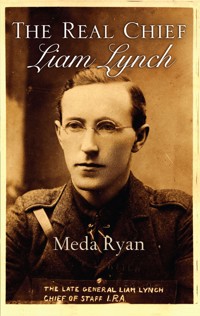

Liam Lynch, Chief-of-Staff of the IRA, was known as 'The Chief' among Republicans, particularly in the First Southern Division. Many of his comrades have wondered why he did not get the recognition he deserved, even though he had been offered the position of Commander-in-Chief of the army in December 1921. Some felt that in the documentation of history, de Valera overshadowed him, while others thought that because of the firm stand he took in holding out for a republic, his deeds of bravery, especially before the Civil War, were downgraded. This is his story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Meda Ryan, 1986, 2005

Ebook edition, 2011

ISBN: 978 1 85635 460 8

Epub ISBN: 978 1 85635 891 0

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 85635 913 9

For copyright reasons, photographs and images have not been included in the electronic book.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Dedication

To the memory of Sheila Ryan

Introduction

While working on a biography of Tom Barry I realised that he did not always see eye to eye with Liam Lynch. Both men were strong-minded Republicans, and though initially Barry’s attitude was more radical than Lynch’s, he was, during the closing stages of the Civil War, much more flexible. At various periods during the Civil War both men belonged to separate divisions of the same ‘divide’ often voting in opposition to one another.

Through working on a biography of Barry, I considered that I had come to understand the man, and, because of Barry’s close links with Lynch, I felt compelled to get an insight into Lynch – the man. It was the clash of personalities, which first attracted me towards investigating the life of Liam Lynch. When I discussed the matter with Seán Feehan of Mercier Press, this compulsion crystallised and led to this biography.

Fortunately my research was aided by original material, especially the personal letters which Liam Lynch had written to his mother, his family and others. The personal correspondence (now held by Liam’s niece, Biddy O’Callaghan) was invaluable, as, in his letters, he often expressed his very private thoughts. It was only possible to use a fraction of the material in these letters, but I hope that in doing so his strength of character, together with the vision, which Lynch possessed, emerges. From his letters, as well as his responses to misrepresentation of him in newspapers, it is obvious that he wanted his ideas and his intentions to be honestly interpreted. ‘I do hope I shall live through this,’ he wrote in a letter to his brother Tom during the Civil War, ‘that future generations will have written for them the full details of all the traitorous acts.’ But such was not to be; he was killed at the age of twenty-nine.

His dislike of hypocrisy is evident in both his words and actions. He always followed his beliefs and never acted through a desire for notoriety. ‘Through the war I have got to understand so much of the human being,’ he wrote to his mother during the truce, ‘that when peace comes, I would wish for nothing more than hide myself away from all the people that know me, or even follow my dead comrades.’

During my early research I wrote to Jim Kearney, an IRA veteran, in connection with a point which I wanted clarified. In doing so I used the word ‘Irregulars’. I quote from his reply: ‘Irregulars! Where did you get that dirty word?’ Later, I discovered Liam Lynch also detested the term, saying it was coined by pro-treatyites as a derogatory label. I have not therefore used ‘Irregulars’ or ‘Staters’ except as part of a quotation. Liam Lynch was known as ‘The Chief’ among Republicans, particularly in the First Southern Division. Siobhán Creedon tells a story of how Margaret Mackin came with dispatches by boat from Dublin to Cork and on to the Creedon hotel near Mallow during the Civil War. ‘I have messages for the Chief,’ she said. Siobhán’s brother, Michael, drove the two women to headquarters where they knew an important meeting was being held. Upon arrival, Margaret had to first go into a side room to undo the dispatches, which she had stitched to her dress. Liam Deasy came out of the meeting saying that the Chief was very busy but would speak to them as soon as possible. Shortly afterwards Liam Lynch emerged, and according to Siobhán, ‘Margaret stared at him in complete surprise.’ Seeing that they did not appear to know each other she introduced them. ‘But,’ stammered Margaret, ‘it was Mr de Valera I wanted!’ Liam Lynch explained that De Valera was in West Cork but would be along in a few days, and that, meanwhile, he would see that the dispatches were delivered. Later, when Margaret explained her dilemma upon seeing Lynch, Siobhán responded, ‘We call Liam Lynch “the Chief” – he is the real Chief! Chief of the IRA.’

In most historical books, references to Liam Lynch’s death merely state that he was fatally wounded in the Knockmealdown mountains; while I accepted the straight-forward view that he died from a Free State force bullet, it was not until I began my research that I discovered a question mark hung over his death.

On 7 April 1935, Maurice Twomey (who was with Liam on the morning he was shot in the Knockmealdowns) unveiled a watch-tower memorial to him close to the spot where he fell. Since 1935 a ceremony, organised by Sinn Féin, is held there each year. And in Kilcrumper graveyard where he is buried, since 1956 another ceremony takes place on an annual basis in which some Fianna Fáil members participate. On the Sunday nearest 7 September (to commemorate the Fermoy raid in 1919) at all venues ‘old IRA’ veterans, together with interested members of the public, attend the organised ceremonies each year. So it has been said, ‘There are two different Lynchs buried!’ – ostensibly two different interpretations of the Republican vision portrayed by the one man.

It is ironic that the grand-daughter of Éamon de Valera, Síle de Valera TD in 1979, at a Liam Lynch commemorative ceremony, hastened the early resignation of the then leader of the Fianna Fáil party, Jack Lynch, when she called on him ‘to demonstrate his Republicanism’: but as John Bowman pointed out in his book De Valera and the Ulster Question 1917–1973, that, while De Valera, during the last meeting with Liam tried ‘to persuade him to abandon military resistance to the Free State, Liam Lynch was concerned lest the decision reached fell short of fundamental Republicanism.’

In a letter to his brother dated 26 October 1917, Liam had expressed his opinion that it was through armed resistance that Ireland ‘would achieve its Nationhood.’ It was his belief that the ‘army has to hew the way for politics to follow.’

Many of his comrades have wondered why Liam Lynch did not get the recognition which they felt he deserved, even though he had been offered the position as commander-in-chief of the army in December 1921; the consensus amongst his compatriots was that, in the documentation of history, De Valera overshadowed him. There is no doubt that Liam’s insistence in holding out to the end, for nothing less than ‘an Irish Republic’ when victory for that cause was becoming increasingly remote, meant that he was alienating himself from other members of the Republican Executive. However, Liam reiterated his viewpoint in a letter to his brother, dated 12 December 1921, ‘As you stated, De Valera was the first to rebel.’ But rebelling as a mere protest was not sufficient: ‘Speeches and fine talk do not go far these days ... what we want is a definite line of action, and in going along that, to use the most effective means at our disposal.’ Because of the firm stand which he took in holding out for a Republic, his deeds of bravery, especially previous to the Civil War, appear to have been downgraded, so much so that he is often mentioned as if in passing.

Yet, historically, Liam Lynch is an extremely important figure because of the part he played in gaining Irish independence – first as commander of Cork No. 2 brigade and later as commander of the First Southern Division. The part he played with Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Liam Deasy, Tom Barry and others, in endeavouring to avoid Civil War, and his efforts to achieve a thirty-two county Republic for Ireland rather than a partitioned state, should not be underestimated. During the Civil War period, as chief-of-staff of the Republican forces, he was the major driving power and spokesman for that section. I believe therefore, that this is a necessary biography.

Meda Ryan

1. The fatal shot

Liam Lynch, chief-of-staff of the Irish Republican Army, rested with two of his travelling companions, Frank Aiken and Seán Hyde, in a house on the banks of the Tar River at the foot of the Knockmealdown mountains. It was the eve of 10 April 1923.

Before dawn they were awakened and told that Free State troops had been sighted. Liam and other members of the Executive had assembled by 5 a.m. at Houlihans, the house nearest the mountains. As they waited for further reports they sipped tea. These men were not unduly alarmed as all of them had, on more than one occasion, stood on the precipice of danger; raids of this nature were an almost daily occurrence, so believing that they had left no traces, they decided to wait.

A scout rushed in at about 8 o’clock with news that another column of Free State troops was approaching over the mountains to their left. Their line of escape was endangered. After months of Civil War, fellow members of the Republican Executive had finally persuaded Liam Lynch that a meeting was imperative, and because of this, a number of members were now caught with their backs to the mountain; Liam Lynch had always feared this type of situation. Though the Free State government was bent on crushing the ‘armed revolt’ and forcing the opposition into an unconditional surrender, Liam Lynch had pledged that he would not surrender:

We have declared for an Irish Republic and will not live under any other law. 1

Since the execution of four Republican prisoners on 8 December 1922, as a reprisal for the shooting of Seán Hales, a member of the Dáil, much of the conflict had begun to lack human dignity; the rules of war were being flouted.2

Already Liam Deasy, imprisoned Republican Executive member and former brigade adjutant, was compelled to avail of the only option his captors left open to him; he signed a dictated document which called on his fellow members of the Executive to agree to an unconditional surrender.3By January 1923 over fifty Republican prisoners had been executed and more had been sentenced to death (eventually a total of seventy-seven prisoners were shot as reprisals, though Ernest Blythe gave 85 as the number of prisoner executions).4Before his capture, Deasy and most of the Executive had come to the conclusion that further bloodshed would be in vain since it had become evident that for them a military victory was no longer a possibility.

However, Liam Lynch was determined that, ‘the war will go on until the independence of our country is recognised by our enemies, foreign and domestic ...’5He was well aware that, if a meeting of the Executive was called, he would have to listen to the words ‘unconditional surrender’ and these were hateful to him. He had fought too hard, suffered too much, to concede all with the stroke of a pen. More than most men of the period, he had tried several avenues in order to secure a consensus in an effort to avoid Civil War. But when the break came he channelled his energies totally into the ideal of a thirty-two county Irish Republic.

Though his comrades had finally persuaded him to at least call a meeting, he had secretly confided to Seán Hyde that he would not be coerced into a surrender position.6This proposed meeting for 10 April 1923 was ipso facto the continuation of the March Executive meeting which ran for three days without reaching a consensus. Lynch, Frank Aiken and Seán Hyde had left the ‘Katmandu’ bunker on 4 April and had travelled mainly on foot towards the Knockmealdowns. On 10 April as he and his comrades groped their way up the mountainside the sound of gunfire forced them to quicken their pace; then there was a lull in the firing. ‘For perhaps twenty seconds the still clear air of the morning was soundless, and then one single shot rang out.’

Liam Lynch fell. ‘My God, I’m hit!’ he cried.7

Over the years since that April morning in 1923 questions have been asked about his death. It is generally accepted that it was a bullet from a Free State gun which hit him, but there are those who say that Lynch had to be removed because he was regarded as a stumbling block in any cease-fire negotiations. Was it because of the speed with which the cessation of hostilities was conducted following Liam Lynch’s death that suspicion surrounded the manner in which he was killed?

As the Civil War had dragged over the winter months and Lynch had continued to believe in the possibility of victory, De Valera, Frank Aiken and others looked ahead towards some form of political recognition. Many of the anti-treatyites had come to realise the futility of the continuance of a war which pointed towards the defeat as well as the annihilation of the principal leaders. The available members met ten days after his death and unanimously elected Frank Aiken to replace Liam Lynch as chief-of-staff. They also appointed an Army Council of three (Liam Pilkington who had replaced Liam Lynch on a temporary basis; Tom Barry and Frank Aiken).

This meeting passed a resolution authorising the Republican Government and Army Council to make peace with the Free State authorities. At a meeting of the Executive and Army Council held on 26 and 27 April, over which De Valera presided, it was decided that armed resistance to the Free State forces should be terminated. A proclamation was drawn up announcing their readiness to negotiate an immediate cease-fire, and the order for the suspension of all operations from 30 April was also issued by Frank Aiken. This was just twenty days after Lynch’s death. It was the initial seed-setting which led to the foundation of the Fianna Fáil political party.

So was Lynch assassinated?

Was he hit by a long-range shot fired by a member of the Free State forces?

In certain ‘pockets’ of the country it is said that there was an organised plot to get rid of Lynch, the belief being that ‘he was a stumbling block for those of the cease-fire, dump-arms element.’

Following Liam Lynch’s death an inquest was held; he was in fact a prisoner – a wounded officer who died in enemy hands, therefore and inquest was believed necessary.

Ned Murphy, a member of the Free State intelligence staff, was out on the round up with the forces on that morning. Having searched Houlihan’s house for any tell-tale papers or documents, Murphy and his section climbed the mountain. He discovered Lynch, who had already been found by another Free State party and placed on a makeshift stretcher. ‘My job was to collect any documents and also to file a report,’ he recalled.

Ned Murphy outlined for me the final events of Lynch’s life as he saw them; these are detailed, analysed and integrated with the inquest findings, newspaper reports and other interviews towards the final part of this book, consequently clarifying the source of the bullet which ended Liam Lynch’s life.

1 Letter to his brother, Tom, 1/11/1917 (Lynch private family papers)

2 One prisoner, representing each province: Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett, Joe McKelvey.

3 Brigade Adjutant, First Southern Division. Liam Deasy, private papers.

4 John A. Murphy, Ireland in the Twentieth Century, p. 57. See also Eoin Neeson, The Civil War in Ireland, p. 190. Following the execution of four Republican prisoners (8 December 1922) as a reprisal for the shooting of Seán Hales (7 December 1922), Cosgrave announced in the Dáil that government policy ‘was one of terror meeting terror’. The last official pro-treaty execution took place on 2 May 1923; see also MacEoin, Survivors, p. 88.

5 Letter to ‘Comrades’, 9 February 1923.

6 Seán Hyde, author interview, 13/7/1974.

7 Maurice Twomey.

2. Early life and vision of Ireland

In the townland of Barnagurraha, under the western slopes of the Galtee mountains, a fifth child was born to Jeremiah Lynch and Mary Kelly Lynch on 9 November 1893, and christened William Fanaghan, soon to become known as Liam.1

At the age of four and a half he was sent to Anglesboro school which he attended for the next twelve years. A diligent and hard-working pupil, Liam is remembered by his teacher, Patrick Kelly, as a ‘mild, gentle boy above the average in intelligence’.

From early childhood, young Liam was aware of the hardships undertaken to make a living off the land; he was also aware of the difficulties under which ownership of the land had been secured. From his home north of Mitchelstown, in the Cork/ Limerick border, he could view the Aherlow River, Paradise Hill, and the towering Galtees. Here in this rich fertile land he learned how his ancestors secured their holdings through sweat and blood. His home, like most of those in the rural Ireland of his day, was a centre of history and storytelling. Families and neighbours would gather round the fireside and tell of the background to their existence, and the long history of the struggle for freedom.

The Lynchs lived in the fertile plain known as Feara Muighe Feine with the royal seat and capital at Glanworth. This was later Desmond land, parcelled out after the confiscation, when thousands of acres were given to Elizabethan adventurers, on condition that it should be planted with English settlers. After Irish natives had been driven from their holdings by the sword, six thousand acres of this rich land was granted to an Arthur Hyde, for which he paid one penny per acre upon undertaking to plant it with English subjects. (One branch of the Hyde family gave us Douglas Hyde, the founder of the Gaelic League and first president of Ireland.)

One of the dispossessed families was a Lynch. Though there is no record how this family survived for five generations, they, like some families who were not among those banished in Cromwell’s ‘to Hell or to Connaught’ dictum, were forced to tolerate being in servitude to the planters. Gradually they achieved tenancy of a small holding from the new landlords. They were in servitude, without rights, property and for a time without legal existence. But they inherited a Gaelic culture and Gaelic tradition. It was into this Liam Lynch was born. His uncle, John Lynch with William Condon rode on horseback to Kilmallock for the Easter Rising. The MacNeill cancellation and the surrounding of the town meant they had to return home. His mother, Mary Kelly had been joint secretary of the Ballylanders Branch of the Ladies’ Land League. Hannah Cleary, his godmother was a Fenian and great storyteller with a wide knowledge of history.

Young Liam Lynch learned that the family farm had been acquired through great sacrifice. This understanding of his background would one day cause him to lead the men and women of south Munster in a fight which would finally destroy the last remnants of the plantation and so give the Irish people control over their own destiny.

At the age of nine, investigations revealed that he had defective eyesight, consequently he had to leave school for a short time to have treatment in Cork and had to wear glasses for the remainder of his life. Being particularly attracted to deeds of bravery, as a child, Liam on one occasion climbed, with some of his school companions, to the top of the Galtymore Mountains pointing northwards to Ballyneety. He spontaneously rendered an accurate account of Patrick Sarsfield’s famous night ride and destruction of the Williamite siege train. Years later he referred to this again in a letter to his brother Tom.2

In 1910 at the age of seventeen the shy retiring Liam left home and entered upon a three years apprenticeship term at the hardware trade of Mr P. O’Neill. During this time he acquired a great taste for reading and especially for books of Irish historical interest. In Mitchelstown he joined the Gaelic League and the Ancient Order of Hibernians and continued his education by joining a technical class. Every Sunday, he returned to his parents’ home at Barnagurraha. In 1914 his father Jeremiah died. Liam was just twenty-one.

Fermoy was a garrison town. It held a larger concentration of British troops than any other town in the county. Kilworth and Moorepark camps contained strong elements of British-Union units. Union Jacks, khaki and recruiting oratory for the British army were very much in evidence. Many young men joined the British army, believing as they had been told, that they were fighting for the freedom of small nations including their own; however, many also questioned this military regime and some, like Liam Lynch, questioned the military strength of a foreign power whose troops occupied his own country. Liam was an avid reader of newspapers, and keenly interested in events abroad. Friends said of him ‘he watched everything and everybody to see where was truth and where was sincerity’. He might have remained an observer were it not for an event subsequent to the 1916 Easter Week Rising which caused him to change his life.

Forty-six organised companies in Cork city and county, though poorly armed, believed that they were denied participation in the 1916 events when they accepted MacNeill’s cancellation of all parades that Easter. Because of participation in the volunteers, some families or individuals were singled out for harassment. The Kents of Fermoy who had been active in the volunteers were the first family to receive a backlash. Thomas, David, Richard and William Kent had not been sleeping at home since the Easter Rising, but on 1 May returned to spend their first night at home.

Early the following morning, the house was surrounded by armed police who said they had orders to arrest the entire family. The Kents armed with a rifle and three shotguns decided to resist. An open conflict ensued when the police opened fire and continued until the defenders had exhausted their ammunition; by this time the police had called in military reinforcements. When the family surrendered, David was seriously wounded, Thomas was immediately handcuffed and not allowed put on his boots, whilst Richard, an athlete, made a bid to escape, but in doing so was mortally wounded.

Liam Lynch was standing on Fermoy bridge that morning when he saw the Kent family having been arrested by British soldiers. Young Thomas was in his bare feet, William and their mother were prisoners and a horse was drawing a cart on which Richard and David lay wounded. Richard was to die two days later at the hands of his captors and Thomas would, within a week face the British firing squad in Cork. It was a scene, which cut to Liam’s very heart, and he associated it with the horror of the executions in Dublin about which he had read. That night he made a resolution that he ‘would atone as far as possible to dedicate his life for the sacrifices of the martyred dead’: he was determined that he would make the Irish Republic a reality; he was now a man of ‘one allegiance only’, believing that the only way to achieve freedom was by force, that it was in arms and only in arms that Ireland would achieve liberty.3

From then on, he did not deviate from his aim, which he pursued with single-minded tenacity and devotion. For this tall, sturdy, agile young man, the action taken by the volunteers in the GPO during Easter Week was a spark which lit the flame to his future. He saw the history of the long struggle of the Irish people for liberty with a new vision. With his brother Tom, who was then a clerical student in Thurles, he would often talk with pride about the events of Easter Week and would speak of the men who fought for Ireland’s freedom. In their intimate conversations he would discuss methods of achieving this freedom for the Irish nation.

As time progressed Liam talked not of dying for Ireland but of living and working for Ireland. His was a logical mind; as a young boy he was an excellent draughts player, quick to see the weakness in an opponent’s position and equally he quickly availed of the advantage. Similar characteristics were evident in his subsequent task of commanding the volunteer force. He was a deep thinker and in the volunteers he saw the raw material which could, if properly forged, become a powerful weapon. Knowing that loyalty and idealism were not enough, he favoured cool, calculated planning coupled with an organised approach to the military problem. In the aftermath of Easter Week, following the arrest of leaders who were deported to internment camps in England, the volunteer organisation disintegrated in many parts of the country. Upon the release of internees at Christmas, and of sentenced prisoners in June 1917, the country was ready for vigorous organisations.

Like many a young man at the time, Liam Lynch took a keen interest in these developments. He had wanted to meet somebody who had taken part in the 1916 Rising and hear the exact details. An occasion presented itself when a farmer from the Galtees told him that he had one of the men who took part in the Rising staying with him. Liam made arrangements to meet the man who was ‘on the run’. He was both surprised and delighted to learn that it was another Galtee man, a neighbour, Donal O’Hannigan. Liam immediately brought him home to his mother at Barnagurraha where he stayed for some time. Liam, still working in Fermoy, visited them frequently and when his brother Tom returned from college, the three met and talked about Ireland’s future. Like many an Irishman, he hoped that the peace conference due to take place at the end of the war would give Ireland’s claim for independence a favourable hearing, yet he was not prepared to rely on the possibility. He wrote to his brother in October 1917, ‘I as well as thousands of others are preparing hard to mount whatever breach is allotted to us ... If we do not get what is our own at the peace conference we will have to fight for it. In a few months we will be able to marshal an army.’4

By this time the organisation of that army had begun on a country-wide basis. Companies were being formed, officers elected and elementary training in voluntary discipline was being organised. When the Irish Volunteer Company at Fermoy was re-organised in early 1917 Liam Lynch was elected first lieutenant.

1 Other members (seven children): Jeremiah who was accidentally drowned in London in 1904; James – died aged 39 of a clot after an operation; Martin – Christian brother died in Kilrush 1964; John remained on the home farm; Tom – priest went to Australia – Very Rev. Dean Lynch PP of Bega, New South Wales, died in Sydney 28 March, 1950; Margaret married locally.

2 ‘I always thought Sarsfield made a daring ride ... Yes, but he burned the guns’ – letter to his brother, Tom 15/11/1919 (Lynch private family papers).

3 Lynch private family papers.

4 Letter to his brother, Tom, 10/10/1917 (Lynch private family papers).

3. Declaration for an Irish Republic

When De Valera was returned in the Clare election of June 1917 with an overwhelming majority it was a clear indication of the mood of the people and their endorsement of the aims of the 1916 men. At the October Sinn Féin Ard Fheis 1,200 Cumann throughout the country unanimously adopted a constitution, the preamble to which declared:

Sinn Féin aims at securing the international recognition of Ireland as an Independent Irish Republic. Having achieved that status the Irish people may by referendum freely choose their own form of government.

At this Ard Fheis, Éamon de Valera was elected president and at the volunteer convention on 27 October, he was also elected president of that body. By being president of the two principal organisations it seemed as if the nation had found a leader; the way was open for the great national movement.

British proclamations of 1 August 1917 prohibited the wearing of military uniform or the carrying of hurleys. On 15 August that same year volunteers were arrested on a large scale throughout the country. This was followed by a hunger-strike. Among the hunger-strikers was Thomas Ashe, who was forcibly fed and died on 25 September 1917. This created disquiet among the volunteers, so the volunteer Executive decided to challenge the British prohibition and ordered parades in uniform to be held throughout the country on Sunday 21 October.

On that day Liam Lynch in volunteer uniform was second in command of the sixty-seven men of Fermoy company who marched out to meet the RIC. Happy with the challenge, Liam wrote to his brother of the two hours drilling: ‘We are to keep drilling until the last man is gone. We mean to break the law of illegal drilling.’ He also warned his brother who was in Thurles College that he was to write on ‘friendly matters’ only as his letters were being read in the post office. He thought that he might be arrested – judging by a letter to his brother on 1 November, he appears to have been disappointed that he was not arrested. His brother however, advised ‘that though it was honourable and good to go to gaol it would be better for the lads to stay out, work harder and give England something livelier than gaol work.’ From then on he was not anxious for imprisonment but he did warn his brother, ‘I am only doing my duty to God and my country.’

Liam O’Denn, the company captain was arrested and Liam was given his place in command of the company. Each Sunday, parades continued and generally when a company captain was arrested another was ready to take his place. Liam Lynch’s philosophy is well expressed in one of his letters:

We have declared for an Irish Republic and will not live under any other law.1

As far as he was concerned Britain could not defeat them except by interning the whole volunteer force. He told his brother in a letter on 9 November: ‘Our parade was not prevented last Sunday but we had made arrangements to carry on elsewhere if such happened. We marched to Ballyhooley with about 100 volunteers where we met Glanworth, Glenville, Rathcormac and Ballyhooley volunteers – in all about 300, and I had the honour to be at their head.’2

One of his principal aims now was to get military training. He even had the mistaken impression that prisoners in Cork jails were getting some form of military training. In a letter to his brother he wrote: ‘I would want to go there at least for a few weeks’ training.’3 He tried to lay his hands on any books that might help him to study military drilling and leadership. He even studied the guerrilla tactics of the Boars in the South African war. He was, however, aware of the surrounding problems in the heavily garrisoned town of Fermoy and he was also aware that, apart from the military parades which they held on Sundays, his group was practically unarmed; they were untrained, had no military assets except a sturdy manhood and a glowing faith in the justice of their cause.

In mid December, when Éamon de Valera came to speak at a public meeting in Fermoy, Liam, dressed in uniform, paraded at the head of the local company to welcome him.

The Fermoy battalion was the sixth of the brigade’s twenty battalions at that time.4 (Battalion commandant was Martin O’Keefe; vice commandant, Michael Fitzgerald; adjutant, Liam Lynch; quarter-master, George Power.) Being elected battalion adjutant gave Liam a wider scope for his activities. A diligent worker, by setting a standard in his own work, he showed what could be achieved. He made it his business to visit one company each week and to study their problems – he urged perfection and impressed on his comrades the importance of the acquisition of arms.

The threat of conscription to the British army hardened the temper of the people against British rule; it also meant that the volunteer movement gained more support from the population. Volunteering had become respectable. Because of the threat of conscription Liam left his place of employment in April 1918. With Michael Fitzgerald, Larry Condon and George Power he devoted himself full time to preparing for active service. By the summer of 1918 he had the first mobilisation unit in active operation.

The British authorities now invented a mythical German plot to justify large-scale arrests of volunteers and Sinn Féin leaders. Apparently, the idea was to deprive the people of leadership, which would, in turn, weaken the national morale. Arrests were made on 17 and 18 May 1918 when seventy-three people were deported to England. As Liam had already left his place of employment he escaped arrest.

He now decided that more arms should be secured for his battalion. Upon receipt of information that, on a certain date, a train, carrying arms, would travel from Mallow to Fermoy, Liam, with the aid of Liam Tobin, mobilised about fifty men between Ballyhooley and Castletownroche to ambush the train. Nothing was left to chance. Wires were cut, cars were mobilised to remove the expected arms captured and the arrangements for their safe disposal was organised. The train was held up and searched, but contained no arms. Nevertheless, as far as Liam was concerned, the effort gave the battalion valuable experience.

Following this episode, Tomás MacCurtain, lord mayor of Cork, visited the battalion and gave Liam instructions which were to be implemented in the event of any enforcement of conscription. Any local problems or any difficulties which might arise in each area were to be dealt with by the brigade and battalion officers. In the Cork brigade it was visualised that the entire force might be called out on active duty, consequently detailed instruction on discipline and on problems of billeting and feeding were issued. Liam outlined a list of activities: cyclist-dispatch riders to man a communication system were established and tested.

An editorial in An tÓglach, September 1918 read, ‘The unanimous decision of the Executive of the Irish volunteers is to resist conscription to the death with all the military force and warlike resources at our command.’5How could a group of men resist force without ammunition and without trained leaders? Headquarters were unable to help. In the absence of arms and ammunition the only immediate advice Liam could give the men was to use pitch forks or whatever was available in the face of aggression; other means could afterwards be pursued.

Liam realised what the task of feeding, clothing and finding shelter for a volunteer force would involve. He also realised that such a force could become an unruly mob, therefore it was important that morale be sustained and that communications be kept at a high level. Now, more that ever, he realised that the acquisition of arms was of paramount importance. Given arms other difficulties could be overcome.

The war in Europe ended on 11 November 1918 and with it the threat of conscription. A young volunteer army had stood together and had won a significant and bloodless victory. Since February, the carrying of arms had been prohibited, and from June onwards a series of proclamations was designed by the authorities to destroy national organisations. Arrests were numerous, creating problems for many units of the volunteers. There was continuous resistance by hunger-strikers in the jails. In addition GHQ issued a policy of resistance on 20 August 1918 ordering the volunteers, when brought to trial, to refuse to recognise the jurisdiction of the court.

Cork County had, by mid 1918, re-organised under the direction of the vigorous Tomás MacCurtain, the brigade commandant.6All GHQ could do was issue general directions and allow each area under their commanders to shape their army. Many who had joined because of the threat of conscription began to drop out and because there were more men available and willing to fight than there were weapons to arm them, morale began to drop. However, Liam continued to drill the men every Sunday and on certain weekdays. He kept impressing on the Fermoy battalion that their objective was ‘a military victory’ and that if the volunteer army did not stick together now and fight, all hope of attaining a Republic would be lost to their generation.

A turning point in Irish history came about through the results of a general election in December 1918. The result, which became available on 28 December showed that, of 105 seats in the whole country, Republicans had captured 73. This was seen as an endorsement of the 1916 men’s action and it strengthened the morale of the volunteers. The Irish people, it seemed, had declared themselves for an Irish Republic, consequently the way was opened to them for further action if the need arose. Liam Lynch, like many other officers, realised that the organisation could not be kept going indefinitely without activity and neither could they be properly trained without the use of arms.

Home Rule, which looked imminent before the Great War, had been suspended for its duration, but it was not honoured when the war ended.

At this stage GHQ decided that Cork would be divided into three brigade areas.7On 6 January 1919 a meeting of officers from the battalion forming the Cork No. 2 brigade was held in Batt Walshe’s house in Glashbee, Mallow. The brigade was formed into seven battalions with Liam unanimously elected as brigade commandant.8Once the conscription crisis ended he went back to his normal employment at Barry’s in Fermoy. Following the meeting and Liam’s election, his brother Tom visited him and found him in an extremely happy mood, but Tom, fearful of what future events might bring, anxiously asked if he realised the full extent of his responsibilities. Liam confidently replied, ‘I’ll be able for it. There is great scope.’ His life and his life’s ambition, as far as he was concerned, was only beginning.9

1 Letter to Tom, 1/11/1917 (Lynch private family papers).

2 Letter to Tom, 9/11/1917 (Lynch private family papers).

3Ibid.

4 Fermoy Battalion – Fermoy, Kilworth, Araglin, Rathcormac, Watergrasshill, GlenviIle, Ballynoe, Bartlemy, and Castlelyons.

5 Vol. 1., No. 2., September 1918.

6 Twenty Battalions with an average of eight companies each, and a total strength of about 8,000 men made up the brigade.

7 Cork No. 1 was in the centre extending from Youghal to the Kerry border beyond Ballyvourney and including the city; Cork No. 3 was in the west of the county, and Cork No. 2 in the north of the county.

8 The brigade area extended from the Cork/Waterford border near Tallow, on the east, to the Kerry border at Rathmore in the west and from Milford in the north almost to Donoghmore in the south. Once the brigade was formed George Power, adjutant began to build up an intelligence service.

9 Lynch private family papers.

4. Love and marriage postponed for Roisín Dubh

The first Dáil Éireann assembled in the Mansion House, Dublin, on 21 January 1919. Every elected representative was invited to be present but only the Republicans attended. Of the seventy-three, thirty-four, including De Valera and Griffith, were ‘absent’ in jail. The Dáil was declared an illegal assembly; prohibition by the British parliament necessitated its members holding meetings in secret.

On 21 January also Séamus Robinson, Dan Breen and the other volunteers from Tipperary ambushed some council men who, escorted by police, were taking gelignite to a quarry. Two policemen were shot and the cargo secured.

As the RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) scoured the country and arrested volunteers and Sinn Féin members, it became obvious that the British government wanted these new-found ‘troublemakers’ in custody.