Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

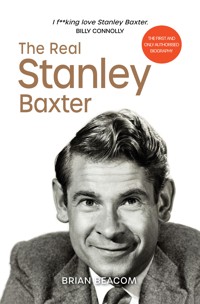

Stanley Baxter delighted over 20 million viewers at a time with his television specials. His pantos became legendary. His divas and dames were so good they were beyond description. Baxter was a most brilliant cowboy Coward, a smouldering Dietrich. He found immense laughs as Formby and Liberace. And his sex-starved Tarzan swung in a way Hollywood could never have imagined. But who is the real Stanley Baxter? The comedy actor's talents are matched only by his past reluctance to colour in the detail of his own character. Now, the man behind the mischievous grin, the twinkling eyes and the once-Brylcreemed coiffure is revealed. In a tale of triumphs and tragedies, of giant laughs and great falls from grace, we discover that while the enigmatic entertainer could play host to hundreds of different voices, the role he found most difficult to play was that of Stanley Baxter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 529

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

ISBN: 978-1-910022-20-7

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book

under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 12 point by Carrie Hutchison

Text © Brian Beacom, 2020

The Real Stanley Baxter

BRIAN BEACOM

This book is dedicated to the force of nature that is Florence Beacom and the quite brilliant Brenda Paterson.

Contents

Foreword – STANLEY BAXTER

Introduction – BILLY CONNOLLY

Preface

Prologue

1. A Star is Grown

2. The Infirm and the English

3. Little Ethel Merman

4. The Norman Bates Experience

5. 3,000 Volt Love

6. The Red Coal Minor

7. De-bollocking8. Carry on Sergeant

9. Buggery, Bestiality and Necrophilia

10. To Be Had

11. Poofter Hell

12. Ménage à Deux

13. Life Gets Glamourouser

14. The Get Out of Jail Free Card

15. Bob Hope or Bill Holden?

16. Stage Frights

17. Fruit-flavoured Mother-love

18. Five-buck Blow Jobs

19. The Scots Cain and Abel

20. Padding, Tits and Wigs

Gallery

21. Kommandant Baxter

22. There’s Nothing Funny About Stanley

23. Spanked Bottoms

24. Dick Swap

25. Loving Sydney

26. Arse Banditry

27. The Wee Culver City Collapse

28. Nymphromania

29. The Suicidal Zapata

30. Love in Leeds

31. The Morally Inhibited

32. Death by Porridge

33. Santa’s Sack

34. Benny from Crossroads

35. The Languid Moon Vanishes

36. Ugly Flowers

37. David Niven’s Blow Job

38. Shadows Becoming Darker

39. The Wasp Sting

40. Cancelling the Newspapers

Endnotes

Personal Life

Stanley Baxter On... Radio, TV and Film

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Foreword

Not all my relations with the press in Scotland have been highly satisfying but one relationship has and that’s with the man whom I’ve chosen to write my biography. He not only has my good wishes but my gratitude. The process of working on the book over almost 20 years has been enjoyable, except in the difficult areas, but the writer was kind and patient, and in the end, all was revealed.

Stanley Baxter

September 2020

Introduction

Stanley Baxter was a radio star when I was a little boy in Scotland. He was also a star of dramatic theatre and vaudeville. When television got its act together, he became a star of that too. His talent is so huge that it is quite difficult to nail down and state exactly what it is. He has also oozed a certain classiness whether he was doing Parliamo Glasgow as an English language professor or impersonating some leggy starlet with the most extraordinary attractive legs you have ever set eyes on!

I found some video tapes of his performances on television recently and found myself laughing out loud at stuff he had recorded 30 or 40 years ago.

Stanley Baxter is a hero of mine and a legend in his own lifetime.

Billy Connolly

Spring 2020

Preface

CHRISTMAS, 1999. The dull calm of a very slow Friday afternoon newsroom was crashed by the harsh trill of the office phone. But the startle was nothing compared to what the caller on the other end of the line had to say.

‘How would you like to write Stanley Baxter’s biography,’ asked the actor’s agent, Tony Nunn, clearly in Santa mode.

Would I? The elusive, enigmatic Stanley Baxter, a man I’d watched on television since I was ten years old, a performer whose TV specials could clear streets, a man of a thousand on-screen personalities who’d managed to reveal very little about his own…

‘We think you’re exactly the right person to handle it,’ said the agent.

Wow. How flattering. I’d interviewed Stanley a few times over the years and we had gotten on well. Yet, this offer was unexpected. Stanley Baxter opening up entirely to a journalist? Clearly, the comedy legend must have thought it time to tell all – and I deemed worthy to become Boswell to his Dr Johnson.

Not quite. ‘Stanley wants his official biography written because he thinks someone will write an unofficial one,’ said the agent, as the sound of a giant balloon burst in my head.

‘This is a way of stopping that happening. But he wants it to come out posthumously. Are you still interested?’

‘Well, yes, Tony. But if it’s coming out posthumously, there’s time for someone else to write it in the meantime? And why choose me in particular?’

‘Stanley reckons the journalist most likely to write the unauthorised version would be the writer who knows him most, the person who’s had most access to him over the years. And that’s you.’

‘Come on, Tony. I’ve never thought of going behind his back. And in any case, there’s so much I don’t know.’

‘Well, anyway, Stanley would prefer to work with you on it. At least, when word gets out you’re writing it that could spike others’ guns. From your point of view however it may not be published for some time. Stanley’s in great health. Are you still interested?’

‘Of course. Yes, great, let’s get it going.’

Arrangements were made to meet Stanley at his home in Highgate Village in London at lunchtime, as stipulated. But as he showed me upstairs into his sitting room, he didn’t look like a man set to enjoy a nice Italian lunch around the corner. He was brooding and anxious as he reached into his pocket, pulled out a wad of notes and thrust them into my hands. My face immediately took on the miserable countenance of the three BAFTA masks on his sideboard. I sensed what was coming.

‘That’s £100, which should cover your air fare,’ he said in sheepish voice. ‘I’m sorry to have brought you all the way down from Glasgow and wasted your time but I can’t go ahead with this. It’s embarrassing, but I’m too afraid.’

I pushed his money back at him. He insisted. I made a desperate suggestion.

‘Look, Stanley, I don’t know what your concerns are but let’s go to lunch at least. I’m here anyway. And during lunch if you tell me your darkest secret, off the record, we’ll both weigh up the consequences and decide where to go from there. If we can’t agree, I’ll be back on the plane to Glasgow, we’ll stay chums and our conversation will never have happened.’

He thought for what seemed the longest moment imaginable. I smiled, but in reality my heart was thumping. The chance to write Stanley’s story was dependent upon his decision at this exact second. Eventually, he shrugged. But it was a warm, wonderful shrug. The lunch was on. And during that lunch he slowly revealed the darkest secret that defined his personal and professional life. And I chewed on the information and smiled and said, ‘Is that it? No robbery, murder or incest? It’s going to be a dull book.’ Thankfully, he laughed.

‘I thought you would think very badly of me,’ he said of his revelation, in soft, thankful voice, sipping on his cappuccino. ‘I couldn’t bear that.’

So the book was on. But Stanley’s story didn’t gush out of the mouth of the man who’d always seemed so confident on television and on stage. Indeed, it emerged in a cautious trickle.

Yes, he would be delightfully indiscreet where others could be concerned, but Stanley was always conscious of how he would be perceived. It didn’t matter if the book was not to be published in his lifetime, he could still be judged by his audience, which, for the moment, happened to be me.

The interview process was lengthy. Over 17 years in fact. As our relationship developed, he offered little insights into his life, layering on detail, correcting himself and developing new, often painful, levels of introspection.

We saw each other more; we holidayed together at his villa in Cyprus. And at one point, the book, now written and approved, was set to be published. Stanley had changed his mind about the posthumous agreement. But on the day of signing contracts he changed it back again.

‘I’m too afraid of what people will think of me,’ he said in soft, appealing voice. ‘I got into this business to be loved. I don’t wish that to stop.’

‘That won’t happen, Stanley. Not when they read the whole story.’

This year he changed his mind again. Now, he’s willing to allow the world to make up its own mind.

Prologue

LONDON, 16 JANUARY 1962. It’s early morning and a young actor is driving his black Ford Zephyr along the streets of London’s West End as the city begins to go about its business. And as he checks his mirror, he realises he has just driven past the two major West End theatres in which his name had been up in lights only a short time ago. The Empire Leicester Square had screened his first film hit, Very Important Person the previous year. A couple of streets away, the Phoenix Theatre played home to the clever satirical comedy, On the Brighter Side.

Today, the driver is set to head west, to Beaconsfield, to recommence filming on Crooks Anonymous, a movie in which he is playing an incredible eight roles and starring alongside screen darling Julie Christie and the very clever Wilfred Hyde-White.

But as he drove around Piccadilly Circus, the actor knew his career was heading in anything but the right direction. And for once, the constant anxiety which so often blighted his life was entirely justified.

As he sidled onto Shaftesbury Avenue, the actor’s worst fears were realised when a newspaper billboard screamed out at him:

‘FILM STAR STANLEY ON MORALS CHARGE’.

His heart was now racing, and he felt sick to the pit of his stomach. His mind began to throw out all sorts of questions; Would he go to jail? Would his career survive this? Could he carry on living?

But another terrifying thought occurred: what would Bessie Baxter say when she heard the news?

1

A Star is Grown

ON A FREEZING late spring night of 1933 and well past most kids’ bedtime, in a tiny hall in the Partick area of Glasgow, a 6-year-old boy in a sailor suit is on stage belting out ‘I’m One Of The Lads Of Valencia’ to a hundred adults squashed up on wobbly wooden seats. Incongruous? Inappropriate? You bet. The song had helped make heartthrob Al Bowlly the biggest singing star of the 1930s, but it was laced with saucy adult lyrics:

You can’t beat a Spaniard for kissing!

Oh, ladies do you know what you’re missing?

The 6-year-old seducer then continues with:

I’ve got such a fine Spanish torso.

It’s just like a bulls only morso!

The little boy will go on to sing hundreds of risqué songs during his career, mostly pastiches of popular hits. But back in Partick, he looks a sight. His hair has been tortured into unnatural waves and his scalp is still burning from scorching tongs, his mother having carelessly touched skin. And if that weren’t enough to involve social services, he’s wearing more make-up than a Parisian streetwalker.

As the boy goes for the big finish, movement at the side of the stage catches his eye. An angry figure in a green velvet frock is half rising from the piano stool and winking wildly at him. The boy panics but picks up his cue from the pianist (who happens to be his mother) and directs a cheeky wink at the fat lady in the front row, as he has been trained to do. The applause instantly doubles.

But the act’s not over as the little lad very far from Valencia produces a stream of celebrity impersonations, from local legend Tommy Morgan to superstar Mae West, to Laurel and Hardy.1

The audience loves it and the pint-sized prodigy leaves the hall with a 10s note and a little certificate, his first prize for Top Entertainer picked up for beating the competition, mostly adults, in these X Factor-like variety shows, before falling exhausted into bed.

Not a normal childhood?

‘I guess not,’ says Stanley, that same little boy 80-odd years on, offering a wry smile. ‘I appeared in a series of those talent shows all over the West of Scotland, in tiny village halls and community centres in the likes of Milton of Campsie or Clydebank, going up against singers, jugglers and ventriloquists. These talent shows were massively popular, but they were tough. Yet, I learned so much about how to please an audience.’

Overall, Stanley enjoyed his stage appearances over the two years, performing to Depression audiences desperate to be entertained.

‘At this time, I felt mostly excitement rather than fear. And when the other mums gazed up at me and shouted “Oh, look at that wee boy! Listen to him do Mae West.” I loved that.’

But paradoxically, as Stanley’s success on the circuit grew, so did his anxiety. This need to be loved by an audience was always accompanied by an acute fear of failure. And the twin emotions were to define the performer for rest of his life.

Stanley’s director-mother Bessie Baxter had no idea of the adverse psychological imprint she was making on her tiny son with his huge smile and pixie ears. Yet, while she would take the reviews from the likes of the Milton of Campsie Gazette in 1933 and delight in showing them to her friends – ‘Young Master Stanley Baxter and his clever impersonations of popular comedians brought the house down’ – she seldom praised her son.

‘It was bewildering for me,’ says Stanley. ‘I’d go on stage and get rapturous applause from a hundred people shouting Bravo! and beating the adults to the prizes. And I’d start to think I must be awfully good.’

‘I sensed my mother was pleased when I’d get the standing ovations, but the problem was she could rarely show it. As my manager and director, she demanded more and more, and probably felt if she praised me I’d try less hard. And over the time, I began to become more fearful. I began to be scared someone else would do better than me on stage and my mother would clatter me.’

What kind of woman would burn her wee boy’s head (‘Ach, you’ve got to suffer for your art, Stanley!’), dress him up like Little Lord Fauntleroy and use fear as an encourager?

Bessie Baxter may have been a Glasgow blacksmith’s daughter, but she was a showbiz mother right out of the 1962 film musical Gypsy, in which Rosalind Russell’s Rose Hovick will stop at nothing to make sure her beautiful daughter June, played by Natalie Wood, becomes a star. But it’s not surprising that Bessie, born in December 1889, lived vicariously and played the Rosalind Russell role with consummate ease. Five feet and two inches of blonde dynamite, the lady was a born entertainer and a talented pianist. Alongside her sisters Molly, Alice (Stanley’s favourite aunt) and Jeannie, the McCorkindale sisters had been sent to Kinderspiels (infant schools that taught performance skills) as little girls.

Stanley’s sister Alice recalls seeing an old family photograph that tells as much about her mum and her aunts than a collection of diaries ever could.

‘Aunt Alice was dressed as Napoleon, Aunt Molly was dressed as a gypsy, my mother was dressed as a man with a suit and a trilby hat and Jeannie was a Scottish soldier. This dressing up, performance-thing was very much a fundamental in the McCorkindale side of the family. I suppose it all helped make the McCorkindales seem more immune to the harsh realities of life around them.’

The McCorkindale girls – think of a Victorian von Trapp Family living in fog, with grey skies and dirty, oily shipyard cranes as a backdrop rather than snow-peaked mountains – would perform to anyone who would listen. Dressing up at home they would excitedly re-enact dramatic tales of exotic heroes and heroines and their fantasy lives. Their living room was peopled by everyone from Romeo and Juliet to Marie Lloyd, the turn-of-the-century music hall star who sang ‘My Old Man Said Follow the Van’.

‘I can remember as a child that the McCorkindales were always running to pianos, singing and dancing,’ says Stanley.

The sisters appeared as vestal virgins or Vesta Tilley, the music hall performer who dressed up as male characters such as ‘Burlington Bertie’. The McCorkindales could shift their programme from Will Shakespeare to Will Fyffe, the Dundonian-born music hall star who satirised drunkenness with his song ‘I Belong to Glasgow’. This incredible homespun drama saw the precocious young ladies develop an imagination way beyond the limits of their experience. On one level they were all fairly poor, ordinary Glasgow lassies, but they loved to think they were rather bohemian and cultured. Even a little eccentric.

Bessie McCorkindale grew up with showbiz airs. As a young lady her cigarette holder contained only Russian cigarettes and she even sounded like the archetypal drama queen, constantly gushing out words such as ‘Wonderful!’ or ‘Marvellous!’ It didn’t matter she’d grown up with her three sisters and two brothers in a small flat in the city’s Argyle Street. Yet, while the sisters could dream of becoming actresses, it could never be a reality. This was industrial, smog-filled, grimy turn-of-the-century Glasgow after all. Not sunny Tinseltown. Actresses were seen as a short step up from streetwalkers.

What was Bessie to do? She desperately needed a little sparkle in her life. Working as a clerk on at Mr Neergaard’s shipping company on Clydeside was a means to an end but her daily existence was entirely starved of the glamour and sophistication she’d see in some of Glasgow’s 100 cinemas or 30 theatres. (Part of the city’s shipbuilding wealth had filtered downward to a populace that craved entertainment.)

‘She decided if she couldn’t become an actress, my mother would create a new role for herself,’ says Stanley, grinning. ‘She’d become a society hostess, with a lovely home where she would entertain her friends.’

How? Like a character from a Jane Austen novel, Bessie reckoned she simply had to marry the right young man. Yet, that wouldn’t be easy. Although an attractive woman with a huge personality, suitors were few. ‘All the good ones have been killed in the war,’ she would often tell friends (there was talk she had been in love with a young Glasgow airman who had lost his life in the Great War). More worryingly, at 35, time was not on her side.

However, fate took her by the hand one night at a local dance when Fred Baxter waltzed into her life. The young insurance actuary didn’t actually send shivers of excitement down her spine (although he was handsome enough) but he added up to possibility. And when he told her he thought her beautiful, she told him she was 29. The couple married soon after but, as in Jane Austen novels, hopes are dashed as often as gentlemen doff their caps.

In her wedding year Bessie opened her arms to embrace the promises of the new post-war Labour Government: better housing, cheaper living costs – it was all so exciting. But she had to close them again fairly quickly after the couple moved into their first home. Glasgow’s gentrified, leafy West End may have been a couple of miles away from the grime and noise of Govan’s many shipyards, but Bessie and Fred move into a tiny, one-bedroomed flat in a tenement building.

Two years after their wedding the couple were still living in that little flat in Fergus Drive. Fred’s salary at the Commercial Union wasn’t enough to buy Bessie the grand Glasgow residence she had hoped for. The family didn’t even have a car, and, heaven forfend, her brother Archie had one. The dream of a more glamourous life seemed to be slipping away.

However, in the autumn of 1925, Bessie found herself pregnant. And with that news a gleam of possibility sparked in the lady’s powder-blue eyes. What if this child became an entertainer? What if she taught Baby Baxter all the McCorkindale skills? Could she grow her own little star?

2

The Infirm and the English

STANLEY LIVINGSTONE BAXTER arrived into the world at 2.15am on 24 May 1926, just 12 days after the end of the General Strike and almost at the same time as the Hollywood release of The Son of the Sheik, the silent adventure film based on Edith Maud Hull’s romance novel in which Rudolph Valentino plays both the father and the eponymous role.

Baby Baxter created his own little melodrama when he revealed a hugely swollen head. An indicator he would one day take himself as seriously as Rudolph Valentino had in his film swansong?

‘It may have been an early sign of megalomania, or perhaps it was because the doctor had to pull me out by the side of the head using forceps.

‘Anyway, my mother blamed the doctor for the swelling and told me later she was so angry she pushed him right across the room.’

Bessie was immediately besotted with her little star-to-be. By day, she would push Stanley proudly around the nearby Botanic Gardens in his swanky Silver Cross pram. At night, the baby boy slept in the only bedroom while husband and wife occupied the bed-recess in the kitchen. And as Stanley grew, any warmth Bessie once had for her husband was saved for her son.

‘I grew up realising my mother was always criticising my father and indeed the whole Baxter clan, exclaiming, “They’re awfy dull.”’

To defend Bessie Baxter a little, compared to the McCorkindales they were. While Bessie and her sisters loved to leap into a four-part harmony of the hits of the period such as ‘Baby Face’ and ‘Bye Bye, Blackbird’, the Baxters were Highland-bred Presbyterians, hell-bent on singing nothing more than hymns on a Sunday.

How did Fred Baxter cope with his wife’s growing coldness? Well, it was made a little easier because he adored her. And so what if she sucked most of the oxygen from any room she walked into, that she was pretentious or her conversation almost inevitably became a performance? He could put up with it. And how could he complain about a mother loving her son? Fred loved his boy too and was determined to spend every moment away from the Commercial Union with him. However, it was a connection Bessie was keen to keep as loose as possible.

‘She wanted it to be about me and her alone. She didn’t go to the theatre with my father to see Tommy Lorne at the Pavilion, Dave Willis singing “My Wee Gas Mask” at the King’s or a vaudeville show at the Empress. She’d take four-year-old me.’2, 3

Bessie focused on her toddler’s performance skills. She played piano for him and taught him to sing and to mime the stars of the day. Stanley learned to become Mae West via Bessie’s interpretation. Meanwhile, Fred Baxter could only watch on from the wings.

Bessie’s overall masterplan began to play out. On 22 May 1930, she produced a baby sister for Stanley. Alice was named after Stanley’s favourite aunt and Bessie Baxter was delighted, if for no other reason than a family of four could no longer be confined to a one-bedroomed flat. Thankfully, Fred could now afford a move, not to the des res Bessie had dreamed of but a rented four-bedroomed, fourth-storey, top floor flat on a hill at 150 Wilton Street.

It wasn’t a swish townhouse but the red sandstone building with its polished green tiles at the entranceway was certainly one of the classier Glasgow closes. What augmented the delight for Bessie however was the discovery that part of the street had once been known by the much grander title of Wilton Mansions. Within hours of picking up the keys she was off to the printers to have her own headed notepaper made up heralding ‘5 Wilton Mansions’.

Stanley says, grinning, ‘5 Wilton Mansions became her own Versailles. We had a big wooden shower – very unusual at the time – and quickly had a phone installed. And when it would ring my mother’s voice would go all Celia Johnson-posh and she’d trill “Maryhill 2680!” She loved all that show.’

Bessie now had the home – and the son – to show off. The front room with its large bay window became the parlour – and the stage – where the first lady had a grand piano installed. And although Fred’s income was limited – he earned less than £1,000 a year – Bessie, ignoring the absurdity of it all, insisted they have a permanent live-in servant. She hired a succession of Catholic maids (Catholics at this time in Glasgow tended to be poorer, from Irish immigrant families), who were actually made to wear coffee-coloured uniforms in the afternoon and black at night. Later, during the Second World War, when there was only a fire for the kitchen, the family sat at the kitchen table and the poor wee maid sat alone at a card table near the stove.

‘It was Upstairs, Downstairs in a Glasgow tenement. You see how she would have loved to have lived the Bellamy life.’

While Glasgow battled the impact of the Depression (the city’s defiant attitude saw it continue to pack its 11 ballrooms and 70 dance halls), Bessie still pursued her dream of glamour and sophistication. Afternoons at 5 Wilton Mansions would see her friends arrive for tea – served up by the maid – and the ladies would play whist or the Chinese board game mahjong, or Bessie would play the piano until it was time for Fred to arrive home from work. (One of her West End friends was Mrs Jackson who had a son, Gordon. As fate would have it, Gordon Jackson would go on to become a British television star, best known for his role as Hudson the butler in the ITV drama Upstairs, Downstairs. Years later Stanley would impersonate Gordon when he parodied the classic series.)

Bessie also began to showcase her little boy. He remembers stepping out from behind the parlour room curtains to impersonate Harry Lauder singing ‘Roamin’ in the Gloamin’, and Marlene Dietrich.4But with the applause from the mahjong ladies still ringing in his ears, Bessie would give Stanley notes, telling him where he’d gone wrong.

‘She was terrified that I would be a failure. My mother had sort of come to terms with her own situation, but she thought the sky was the limit as far as I was concerned – so long as I didn’t fuck up.

‘But when you are continually told “Don’t fail”, regardless of how much natural talent you have to begin with, inevitably, the real worry sets in.’

Stanley was already a top-class worrier in August 1931, when he attended Hillhead High School, a (Corporation-subsidised) private school in Glasgow’s Cecil Street in the West End.

‘I was completely terrified on that first morning, so my mother came into the classroom and sat beside me. I was given a crayon and a bit of paper and the lovely Miss McNeely said encouragingly, “Just draw whatever you feel like, Stanley.” But I was paralysed. My mum said, “What’s wrong?” and I blurted out “I’m sure to get it wrong!”’

Don’t most kids suffer nerves on the first day? Stanley reckons he was more worried than most, thanks to a heightened sense of being judged. But he says there was another problem to contend with; his counting skills were limited. Stanley clearly hadn’t inherited his father’s arithmetic gene.

Yet, although fearful about schoolwork, Stanley wasn’t shy when it came to entertaining. During playtimes, the impish little boy would regale the other kids with stories and impersonations. He was great fun to have around says former schoolmate Eddie Hart. (Bessie wasn’t there to give Stanley notes.)

Stanley recalls the days when his classmates became his audience.

‘On a Friday afternoon Miss Pattison would say, “Stanley, I’m bored, come out and entertain us before the bell goes.” I can’t even remember exactly what I did, probably tell the class about a show my mother had taken me to see at the Empress Theatre, and I’d just talk nonsense and the class would laugh.’

Bessie’s coaching and Stanley’s raw talent was paying off. But the Hillhead High teachers weren’t always pleased with Master Baxter. Thanks to his church hall competition appearances he struggled to stay awake in class. Fred Baxter wasn’t happy either.

Fred hadn’t seen his son perform at this point – the thought of it filled him with dread. But one night, after a show, Bessie told her husband about Stanley’s standing ovations and thunderous applause, and she insisted he see for himself. Fred had to be dragged along ‘to see what all the fuss was about’.

On the bus on the way home Bessie said, ‘Well?’

‘Well what?’

‘What did you think of your son?’

‘I’ll tell you what I think! If I ever go to see that boy on the stage again, have me certified insane!’

The sight of the sailor suit and the Mae West dresses was clearly too much for the subdued Highlander. (Fred however came to eat his words, or rather, Bessie forced them down his throat at regular intervals and he would see Stanley perform many times later in life.)

‘I guess that night must have been horrendous for him, to sit and listen to a big fat soprano singing sharp and then watch a conjurer drop his balls, all before it was Sonny Boy’s turn. No wonder he didn’t want to see it again.’

Bessie Baxter wasn’t entirely unhappy to see her husband unhappy; it meant she had almost total control of Stanley’s development as an entertainer. Yet, if Stanley were now the leading man in Bessie’s life, little Alice was way down the bottom of the bill.

You might assume Bessie would have tried to double her chances of creating a star, as Natalie Wood’s mother had, pushing younger daughter Lana into the slipstream. But Bessie was content with one star to hothouse. Alice recalls she had only three dance lessons. And just as few piano lessons.

‘No matter what I did it was never good enough. And my mum was already caught up with Stanley.’ (Alice would go on to make it as an actress and comedy feed, working the variety theatres of the West of Scotland, but this was more due to raw talent – and perhaps a little osmosis – than encouragement from her mum.)

Meanwhile, Fred Baxter tried to push his son in the direction of ordinary little boy interests. He had him join the Cub Scouts, but Stanley says he hated the very idea of washing out his little dixie can in the mud.

‘I couldn’t be doing with the pack thing. I didn’t mind the little units of kids but not when it became too big. It seemed pointless.’

Former First Glasgow cub pal Bob Reid however recalls Stanley was a little more in tune with cubbing than the actor remembers.

‘He would come alive when he led the singing sessions and he really seemed to enjoy it, keeping the campfires going. He loved to ging gang goolie. We all thought he was good fun to have around.’

Fred also tried push Stanley towards the sports field, but his son believed the very idea of kicking a ball around to be pointless. Stanley reckons this made him less popular with the other boys in his class.

‘I found myself to be not quite part of it all. And I was bullied. As a result, my isolation caused me to befriend others who were outsiders.’ He adds with a wry smile, ‘I was left to play with the infirm and the English.’

His schoolmates who were neither infirm nor English don’t remember it that way. But there’s no denying Stanley was out of synch with many of the boys. And the happy times he remembers came about when performing.

He was popular with some of the girls however, and indeed he had a couple of little girlfriends. But they weren’t selected for the role because his tiny heart was beating fit to burst.

‘I used to flirt with Dorothy Miller and I’d shock the rest of the boys by kissing her,’ he recalls of his mini-performances. ‘This wasn’t the sort of things wee boys did.’

What wee boys – and girls – did was delight in the Saturday morning ABC Minors shows at the local cinema. Stanley lived for the weekend when he would skip a mile down the road to the Hillhead Salon. From the moment he stepped inside the dark theatre the schoolboy realised this was a very special place.

That’s not to say he would whoop and holler every time Gene Autry rode across the range on Champion, or giggle when Laurel and Hardy got themselves into yet another fine mess. Nor did he salivate over space films which used so obviously fake ray-guns or wallow in the westerns where the actors wore phoney cowboy moustaches. (He did like the camp theatre of Flash Gordon however.)

‘For the most part, the children’s films bored me, but the world of the cinema was absolutely captivating. I remember looking up at the screen and seeing the child actors and thinking I could do that just as well.’

What he also loved was the grown-up world of theatre, his mother taking him to see the likes of Henry Hall (the BBC dance band leader) and during the summer months, the Howard & Wyndham (H&W) variety shows. (Stanley would later headline these Half Past Eight shows, which became Five Past Eight Shows, the title relating to the time the curtain went up, running at the King’s Theatre).5The precocious little boy was enthralled by Harry Gordon, the Aberdeen-born comedian and impressionist, actress Beryl Reid, who would later win a Tony Award for her role as a lesbian soap opera star in The Killing of Sister George, and high-kicking, arms-linking international dance troupe, The Tiller Girls. Even Flash Gordon couldn’t compare.

But if Stanley enjoyed variety theatre, his little eyes were on stalks the first time his parents took him across the River Clyde to the Princess’s Theatre. It was there the schoolboy watched his first-ever panto, Aladdin, from a box (Fred landed the treat thanks to the Commercial Union’s connection with the theatre) and gaped at George Lacy, the London-born panto star who delivered working-class gags in a posh accent as the principal comic (with whom Stanley would later co-star with). What this seating meant was that little Stanley could see into the wings. He could see stagehands scurrying around with bits of scenery. He could see wonderful new worlds being created. He could enjoy fabulous, energetic performances and he could see how the audience was lapping it up. It was all frenetic, exciting and daring. This was a world he sorely wanted to become part of. Bessie Baxter noted her son’s envious blue eyes – and smiled.

3

Little Ethel Merman

LITTLE STANLEY NEVER took a holiday from performing. Even on summer holiday. Bessie would never allow it. When Stanley and his aunts, uncles and cousins took off to the little island of Cumbrae off the coast of Largs, during the half hour ferry trip the Baxter clan would be entertained by an on-board accordion trio. No sooner had the families arrived at the boarding house, with the suitcases still in the hall, Bessie would be banging on the lounge piano, offering up her Winifred Atwell’s to the watching world.

‘My father, as you can imagine, would be black affronted,’ says Stanley, shaking his head.

During daytime at the beach Stanley would create little short act plays for his cousins to perform, and the little director would use the rocks, a cocktail cabinet, a lampstand or a sofa as stage pieces.

But at nights he had to step down as director when his mother produced the show.

‘One night, my mother and my cousin Alma and I had to perform for the other guests. Incredibly, Bessie had us recreate a show she had seen on the vaudeville stage, one of the ‘dirty quickies’ based around a ménage à trois, with the plot involving two men talking about their marital problems.

‘Just imagine a nine-year-old boy pretending to be a grown man.’

It’s easier to imagine when you factor in that the schoolboy was incredibly precocious. Meantime, other holidays offered Stanley the chance to reveal his talent for mimicry. When the family went to Portrush one summer, Stanley captured the Ulster accent and refused to surrender it for days afterwards. After holidaying in Blackpool, Stanley sounded remarkably like George Formby (whom he later impersonated on television). Fred Baxter thought this performance-thing nonsense of course but Bessie would hear no criticism of her Sonny Boy. Not even from a teacher. Not even when the teacher realised Stanley was playing with his penis in class.

One day at school, the seeds of sexual awakening seemed to bloom in Stanley before most of his classmates. And he discovered if he played with his little organ with a pencil, via a hole in his trouser pocket, it could be quite pleasurable. But eagle-eyed Miss Morton spotted the secret fiddling, called Stanley out to the front of the class, took out a huge needle and some big green wool and sewed up the gateway to pleasure.

‘That night I went home, and my mother immediately demanded to know why the pocket was sewn up. I muttered, “I’ve no idea.” And my mother cut away the green wool. This panicked me and I cried, “Oh, Miss Morton will kill me if I go back in with the wool gone.” But my mother said emphatically, “Don’t you worry, I’m going to write a stiff note to her.”

‘So I walked into school next day, and as expected Miss Morton yelled at me, demanding to know where the green wool was, and I gave her the stiff note. She sat down to read it and I could see the colour building up in her face. I don’t know what it contained – I didn’t dare read it – but it did the trick.

‘But this was a case of Sonny Boy being backed against someone who had good reason to reprimand me. At the time I was left with a feeling of smug triumph, but it backfired because a little later I was left with a sense of even greater alienation from the rest of the class.’

And Fred Baxter’s input into the pencil and the penis trick? None, because he was clueless.

‘I guess it was because my mother wore the breeks in the family.’

Bessie’s unconditional support for Sonny Boy crossed the boundaries of sensible parenting. When kids at school would tease Stanley for being too self-important (on the days they weren’t laughing at his performances) Bessie would yell, ‘Good! Good! That means they’re jealous – and you’re on the way up!’

Stanley breaks into ‘Everything’s Coming Up Roses’ at this recollection, complete with Ethel Merman voice.

There’s no doubt Bessie’s mothering imbued Stanley with a sense of being special, a necessary character trait in a future showbiz star. But other kids came to see Stanley as an entertainer rather than their pal.

The little Ethel Merman’s sense of displacement at school was soothed however by even more visits to the cinema. Most days on hearing the final school bell, Stanley raced to the movies to get there before 4.30pm – at which time the prices went up from the 5d he paid. Bessie’s prepared banana and marmalade sandwiches (Stanley had decided he would become vegetarian for reasons he can’t recall) were the fuel to take Sonny Boy on his journey into fantasy.

Not children’s films. The world he escaped to was one of eternal triangles, bitter-sweet romances and melodramas featuring screen divas such as Bette Davis in Of Human Bondage or Greta Garbo in The Painted Veil. There are lots of actors who sought comfort in cinema as an escape from the harsh realities of their world as a child. But few aged nine who wallowed in adult relationship tales.

And it’s not as if Stanley was hiding from Glasgow’s searing religious bigotry. Nor was he suffering the endemic poverty of the families crammed ten to a room-and-kitchen in slum areas such as the Gorbals. The schoolboy wasn’t escaping from the city’s human misery, he was escaping into Hollywood’s human misery, in the form of melodramas such as Mutiny on the Bounty.

‘I loved all that angst, but I did quite like Tarzan movies too, although I wasn’t sure why I seemed to like him more than I liked Jane.’

Stanley’s world however wasn’t without real trauma. One mid-October day in 1935, as he made his way home from a school chum’s birthday party, the nine-year-old was approached by a threatening stranger.

‘I had been wearing a kilt and he came up to me and he said, “What have you got on under your kilt then?”

‘Of course, I’d always been taught by mother to be nice to adults, but then she’d never included the coda, “Unless they happen to be paedophiles,” so I mumbled something like, “Well, it’s just my trews.” And at that he lifted up my kilt, exposed himself – and ran off.’

Stanley had no idea who the man was, but although shocked by the experience he told no one. It was a mistake. Three weeks later on Hallowe’en night as he returned home from buying a new false face, Stanley realised the same man was following.

‘It was one of those brown, foggy nights and I was a few streets from my house when I heard the footsteps in the same rhythm as my own. My heart sank.

‘I began to move quicker, and he moved quicker – and quicker – and by the time I reached my close I had broken into a run. I was breathing hard and sweating buckets. But he caught up with me as I flew up the second flight of stairs and he grabbed me.

‘Again, I had been wearing a kilt and he put his hand between my legs and pulled and clawed at me for the longest time. I was grief-stricken. Stunned and frightened out of my wits. I shouted out, “Please, please, I don’t want to! Let me go!”

‘And after a while he did finally let me go. It was my screaming, I guess. And I was left shaking and absolutely terrified.’

No one heard the screams. And again Stanley told no one.

‘But a few weeks later I broke down crying in my bedroom one night and told my father about it. Like a lot of children who are abused you wonder if you are to blame in some way. And I suppose to absolve some of that guilt you confess.’

Fred Baxter, unusually, took control of the domestic crisis.

‘He explained to me that there were quite a lot of men around who do this sort of thing and said, reassuringly, “You are not to worry about it, Stanley.” He added that it had happened to boys in his class. He then said, “You must point out this man to me because it’s against the law, you know.”’

Stanley never did see the child molester again. And Fred’s patient counselling had helpedallay the worst fears. Interestingly, the experience brought about a father and son closeness which had never manifested itself before. Nor was it to ever reappear. Bessie Baxter would make sure of that.

Another story of sexual discovery suggests Stanley wasn’t entirely alienated from his school chums. Now ten, he and his little friends would get together for group masturbation sessions in each other’s bedrooms in pursuit of the collective erection. And perhaps, on a good day, the individual Etnas would erupt.

‘The wanking parties were not uncommon. Not at all,’ says Stanley. ‘And it wasn’t all little poofs-to-be, getting together. It was just something someone did.’ (Indeed. Willy Russell writes extensively and coloufully about the same group sex adventures of little boys in his novel, The Wrong Boy, as does Roddy Doyle in Angela’s Ashes.)

Bessie did believe however that Stanley’s little chums were corrupting him. There were signs that Stanley’s polite West End tones were being infected by his little school pals, many of whom adopted the Glasgow vernacular in order to avoid being tagged public school pansies.

This is not to suggest that Stanley’s diction had degenerated into Gorbals working-class, later used to wonderful comic effect in his classic Parliamo GlasgowTV sketches; but he certainly didn’t speak like a tiny Trevor Howard. The new Glesga accent had to go. Received pronunciation was vital.

‘I was rushed down to the College of Music and Drama to see a man called Percival Steed,’ Stanley recalls with real drama in his voice, as if he’d been discovered to have had head lice and sent to the nit nurse.

‘His character perfectly suited his name. He was an eccentric Englishmen who was bald but with frizzy hair at the side and he looked like he’d been created by Dickens.

‘To develop our speech, he would encourage us to use our diaphragm, and he’d point out the geography of this organ. But curiously, we learned later that with the little girls he taught, the diaphragm was a little higher up.’

Stanley’s speech hardly improved during the Steed period, but meanwhile his acting skills did, thanks to Aunt Alice who’d dress him and his cousins up as actors and rehearse them in the likes of scenes from Hamlet. Stanley once played Hamlet to cousin Sheila’s Queen of Denmark and he managed to find laughs in the performance. (If future directors of serious theatre had seen this, they’d have realised it was pointless trying to contain Stanley’s obvious predilection for comedy.) Here was yet another example of Stanley being stage-managed by adults who lived to perform. And he was being applauded by them. The words of encouragement by Ethel Merman rang out in his head. He had begun to believe them.

4

The Norman Bates Experience

ACT TWO OF Stanley’s school life saw him move up to the Seniors where, he says, he felt even more out of sorts than he had at primary. It didn’t help he was under male tutelage for the first time. And not only was Form Head Mr Fletcher a man, he was also ‘a man’s man’, a games master. Stanley says Flecky was totally confused by this rather effete young boy with the Peter Pan ears who didn’t know which end of a ball to kick.

‘He was really quite a decent bloke, but I think he was actually embarrassed for me. I can remember the class being asked to bring in some work they did at home, a lamp they’d made or whatever, and I brought in poetry I had written.’

Mr Fletcher worried about Stanley. The boy seemed bright enough but this wasn’t reflected in his exam marks. Stanley was also worried; it was bad enough being consigned to the infirm and the English without being trapped in the lower-stream classes with the hard of thinking. But he just couldn’t focus in class.

‘My parents were so worried about my poor performance that they threatened to send me off to boarding school, thinking this would improve me. Luckily, I knew they could hardly pay the fees at Hillhead.’

The glorious summer of 1938 and the arrival of the Empire Exhibition which came to Glasgow’s Bellahouston Park distracted Stanley’s mind a little from the dreaded exam results wait. But, when the circus left town, Stanley was left with the rubbish in the form of low exam marks. And he suffered the indignity of being shoved into the lower of the two First Year classes. The part of Dunce was definitely not the role he would have chosen.

But not all aspects of the schoolboy’s life was so depressing. Just before he turned 13, a leading lady entered his world and together they performed wonderfully together. The theatre was Stanley’s bedroom. Bessie was still employing a succession of young ladies as maids – she had her standards to keep up – with names such a Gracie Glancey, Sadie Thomson and Cathy Scott. But Cathy considered her role in looking after the Baxter family to have the widest remit.

‘She was 14 at the time, and one night in the kitchen, while the family were in the living room, she just set upon me. Cathy was a very sexy girl and I was completely randy. And there we were getting up to all kinds of fun, everything I suppose but full sex. So then I took her to my bedroom where I tried my very best to fuck her. But she drew the line at that. However, these little bedroom encounters went on for a while – until my mother began to suspect.’

Bessie, still desperate to stage manage her Sonny Boy, was to play the Fear Card, the psychological weaponry she carried in the way other women carried a compact. In a scene with resonances of the Norman Bates Psycho experience, Bessie worried her son so gravely about the consequences of fooling around with the fairer sex he froze with fear.

‘She started telling me about these two boys who once took a wee girl into a haunted house up the road and did terrible things to her. And they were birched! Beaten with sticks! Well, that was it. I wouldn’t dare touch Cathy from then on. And Cathy got so frustrated that I wouldn’t keep on playing. My mother had put the kybosh on any openings for me.’

Stanley and Cathy were reduced to playing Lexicon, a Scrabble-like game of the period. Which could still be rather dangerous.

‘Cathy would try and come up with rude words whenever possible. I remember once playing with her, Alice and Alma, and Cathy placed the letters ‘UCK’ on the table. Then she looked up at me with big, simpering eyes and said, “I can’t think of a letter to put down to make a real word, can you, Stanley?” At this point I covered her attempts, to stop Alice seeing what was going on.’

He could have suggested an ‘S’ but that would have compounded Cathy’s frustration. As it was, the rejected maid announced her departure from 5 Wilton Mansions. And when the day came, Lana Turner couldn’t have played the scene any better.

‘Cathy said a polite goodbye to everybody then when it came to my turn she mouthed a soft and alluring, “Bye, Stanley,” and ran up and kissed me hard right on the lips, for the longest time.’

Bessie almost choked on her own tongue.

‘My mother then played it down, of course. She said later, “That was awful nice. She was very fond of you right enough.”’

It wasn’t just that Bessie had a suspicion that Stanley and Cathy were soon-to-be lovers and was terrified her Sonny Boy would father the maid’s child.

‘She didn’t want me going with anyone else,’ he says, softly. ‘She had to be the only woman in my life.’

With Cathy gone home, and a new replacement installed (who had neither the looks nor the sense of adventure), life looked grim for the volcanic schoolboy. Yet world events were to intervene and ensure Stanley had more than his libido to think about. In 1939, it seemed only a matter of time before Glasgow became a prime target for the Luftwaffe; the city’s shipyards, munitions and naval vessels were essential to the war effort.

As a result, fearful parents decanted their kids to relatives around the safer areas of country. Rather than pack Stanley and little nine-year-old Alice off to live with distant relatives or even well-meaning strangers, Bessie decanted Stanley and Alice off to the safety of Lennoxtown, a village 20 miles outside Glasgow. There they lived with a schoolmistress friend of Aunt Alice, Kate Taylor. Bessie hated the six months living with Ms Taylor because the teacher was every bit as bossy as she was. And Kate Taylor reckoned The Performing Baxters were too much to bear. What was especially poignant about the six months in exile was, as far as Stanley can recall, his dad never came to visit.

‘He had to work during the week of course and perhaps he didn’t get on with Kate Taylor. But I really think my mother told him not to come. I only appreciated later how lonely it must have been for him to be back in Glasgow alone without his family.’

When it looked as though the Germans had decided not to wipe Glasgow from the face of the earth, Bessie and her brood returned home. Stanley was delighted to see his dad and at the same time meet a new chum who’d arrived at Hillhead High. Norman Connolly wore thick glasses, was as thin as a ration coupon and had an obvious speech impediment.

‘I guess Norman came into the category of the lame, infirm and the English, all of whom were bullied mercilessly at school. I guess he liked me because I was aware of that.’

Norman’s dad was a clergyman and his mother taught Classics at a school in the south side, but ‘could have been mistaken for a bag lady’.

‘His shoes were always held together by bits of string just like those of his brother, the brilliant James Logie Baird. Norman lived on Colebrooke Street, just along from Glasgow Academy, in a home that looked like the House of Usher, with cats climbing all over the kitchen table.

Stanley and his new oddball chum would hang out in Norman’s wee bedroom and listen to records by Stéphane Grappelli, the French jazz violinist and his guitarist partner Django Reinhardt.

Their music appreciation sessions were halted when Stanley was enlisted by the BBC. Kathleen Garscadden, a producer of the hugely successful Children’s Hour radio programmes, had been talent spotting, searching out the drama stars of the future, when she came across Stanley singing at a Band of Hope concert in his church in Belmont Street, Glasgow.6Dressed in his tailcoat, he performed a Fred Astaire and a Harry Lauder turn. Garscadden had discovered exactly what she was looking for.

‘Up until this time Auntie Kathleen, as she was called by the kids in her series, had been using a very small and very nice lady called Elsie Payne, who specialised in playing small boys. I guess Auntie Kathleen figured it was time to replace Elsie with a real boy.’

Stanley Baxter was to become that real boy, and a professional actor.

‘The drama was called The Unicorn Stamp, I remember they had to put me on a box to be at the same height as the rest of the actors. I can’t recall what the show was about although I think it was pretty daft. Regardless, it worked, and I was offered a whole series of roles – at a guinea for each one.’

Children’s Hour, recorded on Queen Margaret Drive, just a few hundred yards from his home, was the start of Stanley’s professional career and he managed to complete more than a hundred performances before being called up for National Service, loving every moment of his time on air.

Almost.

‘I remember one show called Trader Horn, which I think ended with two children being swept out to sea – it was a real cliffhanger – and I thought it was wonderful. But to my horror, to stop the listening kids having nightmares, Auntie Kathleen stepped in and announced that Archie and June would be alright in the week ahead and “Not to worry, children!”’

‘I thought, “Fuck it. That’s spoiled it!” But regardless of the spoiler I fell in love with radio broadcasting.’

Bessie’s delight at Sonny Boy becoming a radio star was uncontainable, except in front of Sonny Boy himself. Fred Baxter was initially uncomfortable with Stanley’s new radio work; even the hint of an entertainment career worried the actuary. But gradually, Stanley’s radio performances drew his respect. Still 14, Stanley also found his way into theatre and performed with an amateur company the Nessie Night Club. During rehearsals he became friendly with amateur actor Alan MacKill, a man in his 40s. It was a chance meeting which would later have a major impact on Stanley.

But while radio provided the real excitement in his life, sadly there was crackly interference from school. His tall and imposing headmaster at Hillhead High was a man with a rather Dickensian – and ironic – name. Dr Merry liked to single out Master Baxter for special treatment. But it was never positive. During assemblies he referenced Stanley’s radio success but pointed out it was all rather pointless if academic results didn’t match.

‘It’s called sadism, isn’t it?’ says Stanley, the anger still rising when he thinks about the one-dimensional outlook of his educator.

Stanley’s schoolmates such as Tom Forrester however were ‘in awe’ of the radio star. ‘But of course Glaswegian boys would never acknowledge they had a talent in their class,’ says Tom. ‘It wasn’t the thing to do.’ Stanley’s separation from the mainstream saw him spend much of his free time at the House of Usher or at the movies, very often now with his mother. On the night of 15 March 1941, Stanley and Bessie sat in the stalls of the Grosvenor cinema watching The Lady in Question.7But the real drama was taking place outside the cinema.

The Luftwaffe had finally chosen to unleash its fury upon Glasgow. After raining down their death loads onto the shipbuilding town of Clydebank on the Clyde estuary, the returning Germans unloaded their remaining bombs onto the leafy, genteel West End of the city. While Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford played out their emotional turmoil on screen, outside, people were running for their lives as homes were being demolished and streets destroyed. Stanley and his mother were unaware of Hitler’s flying hoards until they, and the rest of the audience, tried to leave the cinema and were barred at the door.

‘We were told Glasgow was being bombed, and to sit tight.’

All the captive audience could do was await the all-clear and try to sleep in their seats throughout the night.

‘I was terrified. My dad was at home looking after Alice and we had no idea if they’d been bombed. We just had to sit there all night while the cinema played music, the same four songs on a loop. I remembered all the words to all of them for years, but they’ve slipped away now.’

Stanley had no idea of the devastation which was being rained down on Glasgow. The Luftwaffe, aiming to destroy the shipyards, had dropped more than 1,000 bombs, most landing in nearby Clydebank, just a few miles away. (It was later discovered that 1,200 people had died and 1,000 seriously injured.)

The West End of Glasgow wasn’t spared being showered by terror. The next morning, Byres Road looked like a post-apocalyptic nightmare. The street was entirely covered in swirling white plaster dust and there was powdered glass everywhere. Standing on the pavement surveying the scene, Stanley felt he was in the inside of a snow ornament.

‘I looked across the road and McKean’s Pork Butchers had been totally destroyed. Then we heard that a parachute-mine had hit Wilton Street, some of the streets around my house had been blitzed, and my mother expressed the only declaration of concern for my father I can ever remember. She said, “Oh my God, I hope he’s alright.” We got home eventually – and he was.’

The following day the bombing continued, and the Baxter family spent the night in a doctor neighbour’s safer ground-floor flat at 151 Wilton Street, or rather they spent it under the doctor’s big dining table.