10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

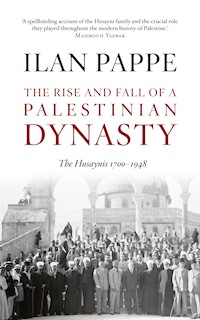

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

'Along with Edward Said, Ilan Pappe is the most eloquent writer of Palestinian history.' New Statesman The Husayni family of Jerusalem dominated Palestinian history for 250 years, from the Ottoman times through to the end of the British Mandate. At the height of the family's political influence, positions in Jerusalem could only be obtained through its power base.In this compelling political biography, Ilan Pappe traces the rise of the Husaynis from a provincial Ottoman elite clan into the leadership of the Palestinian national movement in the twentieth century. In telling their story, Pappe highlights the continuous urban history of Jerusalem and Palestine. Shedding new light on crucial events such as the invasion of Palestine by Napoleon, the decline of the Ottoman Empire, World War I and the advent of Zionism, this remarkable account provides an unforgettable picture of the Palestinian tragedy in its entirety.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

ILAN PAPPE

The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty

The Husaynis 1700–1948

SAQI

First published in Hebrew asAzulat Haaretz: HaHusaynim Biographia Politit by the Bialik Institute, Jerusalem, in 2002

First English edition published by Saqi Books, 2010 This eBook edition published 2011

eISBN: 978-0-86356-801-5 Copyright © Ilan Pappe 2010 and 2011 Translation © Yael Lotan 2010 and 2011

Every effort has been made to obtain necessary permission with reference to copyright material. The publishers apologise if inadvertently any sources remain unacknowledged and will be happy to correct this in any future editions.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

SAQI

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RHwww.saqibooks.com

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Prologue

1. The Making of a Family

2. In the Shadow of Acre and Cairo

3. Struggling with Reform, 1840–76

4. The Death of the Old World

5. Facing the Young Turks

6. In the Shadow of British Military Rule

7. British Betrayal and the Rise of the National Aristocracy

8. The Grand Mufti and His Family

9. The Great Revolt: The Family as Revolutionary Aristocracy

10. The Family in Exile

11. World War II and the Nakbah

Epilogue

Family Trees

Endnotes

Bibliography

Photographs

Index

Foreword

This book is a political biography of the Husaynis, the leading clan in Palestine for many years. The family appears here as an informal political organization whose activities have dominated Palestine’s political history for almost 250 years.

Although historians have followed the trajectories of such elites quite successfully in the past, they have never focused on one particular family.1 Historians’ central interest has shifted over time from families as political elites to families as identifiably crucial social units. Historicizing a family is a fairly new scholarly approach, although one quite familiar in fictional works from both the Arab world (such as those of Naguib Mahfouz) and in Europe (such as those of Thomas Mann). In this respect, the scholarly venture is orientated toward the non-elite – part of an attempt to write ‘a history from below’.2 This biography of the Husaynis is inspired by, but does not reflect, the new scholarly focus on the Middle Eastern family and its place in the local society.

Since this book focuses on elite history, it therefore does not examine the family’s internal dynamics, structure, rivalries and other features that characterize social research on the family in Middle Eastern history. These are all worthy subjects that will surely be explored by others in the future. The purpose here, however, is to analyze this Palestinian family, the Husaynis, as the most significant informal political association prior to the appearance of national movements and political parties – a political organization whose narrative is representative of Palestine and the Palestinians over a period of two and a half centuries.

The family became an affiliation, and its name allowed individuals to wield influence and establish leading positions in their local and later national society. All the positions that could affect society in Jerusalem and eventually in Palestine as a whole could only be obtained through the family’s power base. As such, its members are considered here according to their political weight inside and outside the family. The central figures of this narrative are those individuals who held official and unofficial positions as the heads of the family. Only a few Husaynis who were less politically significant are mentioned (for instance, poets, writers and successful businessmen). This leaves, of course, much research to be done in order to achieve a more focused view on the social history of the family.

A political biography of a large family offers a historical perspective with many advantages for writing a fresh historiography of Palestine. It enables historians to detect patterns of continuity over fault lines that, in hegemonic narratives of Palestine, seem decisively to divide the country’s history into modern and pre-modern periods or Zionist and pre-Zionist histories. The family’s political history is one way, by no means the only one, of telling the story of the continued human and cultural presence in the land of Palestine. By focusing on the Husaynis throughout their transformation from a provincial Ottoman elite into the leadership of a national movement, this biography is, I hope, a constructive way to demonstrate how Palestinian society existed and developed before the Zionist settlement or the British occupation began.

Which brings me to the second principal motivation for writing this book. I wanted to tell the story of Palestine through the history of its leading family as a way to correct the common so-called truisms and to challenge some of the conventional mythology about its past. There is no need to elaborate here on why Palestine’s past is relevant to the contemporary Middle East and beyond, but it is still necessary to gain a better understanding of this history.

By studying the Husaynis, one recognizes that Palestine was never an empty territory waiting for a landless people to inhabit it. Palestinian and other historiographies already show that this land had long had a society and an economy. This book hopes to complement such historiographies by humanizing a landscape described by travelers such as Mark Twain as arid and uninhabited. The Husaynis’ continuous presence at the top of a complex social structure in Jerusalem throughout Ottoman rule (1517–1917) attests to the falsity of the common view of Palestine on the eve of Zionist settlement (1882).

A third reason for choosing the Husaynis as the focus of this narrative was their leading role in the Palestinian national movement from its inception around 1908 until the end of the British Mandate in 1948. By looking at the family, I hoped to gain much greater insight into the Palestinian struggle after the country was colonized by the Zionist movement and occupied by the British Empire. The family’s dominant political role in Mandatory Palestine forms a link in a continuum stretching back to the early Ottoman years. From the Husaynis’ perspective, one can better comprehend how the Palestinian political elite regarded the British presence and the Zionist movement: this point of view highlights the Palestinian predicament and failure, and consequently the tragic catastrophe of the 1948 Nakbah.

Finally, this book is specifically geared towards a ‘Western’ readership. It was originally written in Hebrew in an attempt to challenge hegemonic Israeli–Jewish perceptions of the country’s history. In contemporary Israel, pre-1882 Palestine is still commonly viewed as having been an uninhabited land that was developed only when Zionism, and with it Western modernity, reached its shores. Moreover, Palestinian political life after 1918 has been portrayed in both scholarly and popular literature as that of primitive tribesman, fanatic Muslims and hateful sheikhs. The text in Hebrew attempted to humanize, not idealize, the Husaynis, both because of their paramount position and because they are relatively well-known (due to the accusation that al-Hajj Amin was allied with the Nazis in the Second World War, and more recently because of the politics of Faysal al-Husayni).

In the West, and particularly in the US, similar views reign, and thus similar attempts are required to redress a biased and hostile image of Palestine and the Palestinians. This seemed to me an especially urgent task after 11 September 2001 and the second Intifada.

Hopefully, other more scholarly benefits will emerge from this work as well. One such byproduct, but by no means its principal objective, is that it is among the few histories of Arab Jerusalem that cover both the Ottoman period and the mandatory era. There are focused monographs on Ottoman Jerusalem and a very few others on post-1918 Jerusalem, but there are hardly any continuous urban histories of the city.3

Ilan Pappe, London, 2009

Introduction

THE NARRATIVE

This book is a narrative, the story of a family. In general it is purposely light on analysis. It moves along slowly in the hope of allowing the reader a closer look at the life of the Husaynis. It is also a descriptive narration. It leaves the reader to draw the more obvious conclusions about the patterns of continuity in the history of Palestine.

I chose a descriptive rather than an analytical approach because I wished to zoom in on the dramatic events that shaped the lives of people in Palestine and to try to reconstruct how these events were experienced by individuals with names, distinct locations and discernable emotions. From Napoleon’s invasion to the Tanzimat, the British occupation and Zionist colonization, events are examined through the eyes of the family and not just from an ‘objective’ historical perspective. This means that some events that look important to us in retrospect were not important in the eyes of the family, and some we disregard today were life and death issues then. (A locust invasion could have been seen at the time as more disastrous than French occupation.) For this reason the book goes into minor details while the dramatic, well-known historical events are sometimes left in the background.

The wish to tell a narrative transcends the choice of a family as a subject. There is a desire to plot a tale that is loyal to the facts but that has its own rhythm, flavor and color. Hence, I allow myself, not too often I hope, to speculate – using common sense – about people’s feelings, emotions and considerations. I feel this is part of the humanization of history.

But this subject does also deserve an analytical context. So I would like briefly to introduce the proposed analytical context for this narrative, some historical background information that will benefit the reader’s understanding of the narrative and the sources I have relied on in constructing this story.

THE ANALYTICAL CONTEXT

Apart from being a political biography, this book is also very much an urban history – both Ottoman and mandatory. Although the book does not pretend to rise to the level of micro urban social histories such as André Raymond’s on Cairo, Kenneth Cuno’s on Mansura, Abraham Marcus’s on Aleppo, James Reilly’s on Hama, Leila Fawas’s on Beirut, Michael Reimer’s on Alexandria or Dina Khoury’s on Mosul, amongst many others, it has something in common with these works.1 They helped us to challenge the notion of Ottoman decline that allegedly began in the sixteenth century and continued with the economic stagnation of the eighteenth century before the advent of the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt in 1798. The narrative of this book hopefully challenges the notion of ‘decline’ in that period by showing how Arab-Ottoman elites maintained their position through a complex web of relationships with the center of the empire as well as with European powers and their representatives. This is a reality that cannot easily be reduced to the notion of ‘decline’.

NOTABLES AND THEIR POLITICAL ROLE IN HISTORY

The Husaynis were part of the urban elite in the Arab world. This elite dates back to the pre-Ottoman period and was present when the Ottomans conquered the Arab world in the early sixteenth century. Nor were these local elites replaced by the Ottomans’ ‘open occupation’.2 But with time, when the new rulers of the Arab world realized the benefits of taxation and direct power, they installed a more complex administration, many significant members of which were brought from the center of the empire. The Ottomanization of the provinces in the Arab world included, among other things, the reshaping of the local urban elite. But even within this restructuring, the families, which Gibb and Bowen and later Albert Hourani called the ‘notables’, continued to play a crucial role.3 These notables, to which the Husaynis belonged, were an informal elite consisting of the richest, the most influential and most prestigious families of merchants, ulama and civilian and military officers. This was not a well-defined class, and ‘notables’ are not a sociological concept but rather a political one. The term denotes those who play a role in the political system and suggest how this role is implemented.

In the early eighteenth century, the system stabilized and the local elite were included within the imperial matrix of control and sovereignty. As Ehud Toldano remarks, this was not systematic planning on the part of Istanbul but rather a piecemeal, ad hoc policy responding to events on the ground. An elite position in the empire required a high office, which enabled the holder to acquire wealth (although wealthy people did not necessarily win high positions).4

Ira Lapidus taught us that the core of this elite was the pool of Islamic scholars, the ulama. They appeared in nineteenth-century Syria as notables who descended from prominent eighteenth-century families who supplied the officials for the religious posts of mufti, khatib (preacher) and Syndic of the Descendants of the Prophet. They also managed the awqaf and had strong support from merchants, artisans, Janissaries, and the town quarters.5 The Husaynis belonged to the Syndic of the Descendants of the Prophet – the Ashraf families. This was the family’s main source of power, and through it its members held hereditary offices throughout the Ottoman period.

THE ‘POLITICS OF NOTABLES’

A more focused look at how the notables remained in a high position for so long can be obtained with the help of a concept developed by Albert Hourani for describing and analyzing their political career: the ‘politics of notables’.6 In many ways these ‘politics’ are the key for understanding the urban politics of the Ottoman provinces (at least in the Muslim provinces). The ‘politics’ were a mode of behavior, a ‘practice’, a Weberian concept put forward by Hourani to explain their prolonged political survival. The wider context of this kind of urban history is European patrician history. It is tempting indeed to use the term ‘patrician’ for these people, but it is safer to employ the term ‘notables’ as it is probably the closest to the term ‘a‘ayan’ used at the time. There are other possible terms from the period as well as new ones, but for the purposes of this book I am content to use ‘notables’.

This practice is in essence the ‘politics of dependence and coalitions’, practiced by people in the city and the area around it with their notables and through them with their ruler. Such a mode of behavior can work when there are ‘great’ families or ‘grandee’ families – more akin in the greatness accorded to them to the medieval families of Italy than to that enjoyed in medieval France and Britain, as Hourani remarks.7

The notables enjoyed considerable independence in running the affairs of the cities in the Arab Ottoman world. These families won this relative autonomy because they had access to the rulers of the empire – in the case of Jerusalem, to regional capitals such as Damascus, Acre and Beirut as well to Istanbul and Cairo. This enabled the notables to represent their society before the powers that be. Their prestige in the eyes of the empire stemmed from their standing within their own society.

Other factors also affected the relative independence and authority of the urban notable families. The Husaynis’ ability to compose effective coalitions with forces within and without the city is a major feature of this political biography. The key word is ‘coalition’, and it was such a powerful asset that it served the Husaynis as well in the eighteenth century as it did in the twentieth.

As Hourani sensed even before going into a particular case study, the need to form coalitions increased the tendency ‘towards the formation of two or more coalitions’.8 These formations are traced in this book and are indeed a vital factor in the political history of Palestine in the period under review. In this context, Hourani makes additional remarks that are relevant to the history of the Husaynis: the coalitions were challenged because they were not institutionalized and were fragile because they demanded an almost impossible balancing act between the families’ interests and the policies of the rulers. But it is exactly this balancing act that explains why the Husaynis were leaders of such coalitions for so long: they had the support of the other families in Jerusalem and access to the rulers.

The formation of coalitions was part of the habitual circumspection built into the ‘politics of notables’. These coalitions were not part of a fixed institution; they were far more fluid formations. Occasionally, one party left the coalition for another, disappointing an ally and aligning with a former foe. These shifts also occurred because of the ‘divide and rule’ policies of the central government. Therefore the notables’ ‘modes of action must in normal circumstances be cautious and even ambiguous’, as illustrated by how the Husaynis led revolutions against rulers or shunned others or left them behind when convenient.

As it had been a century before, at the beginning of the nineteenth century ‘the politics of notables’ was very much a politics of ulama. Hourani remarks that their scholarly background placed the ulama notables closer to the ruler than to society.9 But this changed with the secularization of the notables at the beginning of the twentieth century. The notables of religion became the notables of nationalism.

Within society the notables were at the top of the hierarchy, and in the empire they were a substratum below the officials governing the provinces from the capital of the main province or, later on, directly from Istanbul. Among the notables, primus inter pares seemed to be the rule of the game – one family would hold this advantageous position. The position of seniority was the naqib al-ashraf, which until the 1860s was one of the most coveted in Jerusalem next to that of the mufti, the most senior religious position to which a notable could aspire. An appointment as naqib al-ashraf carried with it certain duties as an arbitrator, as a representative of certain awqaf and as an objective witness in matters involving local elite groups.

The titles and functions of notable families were inherited from father to son, making the Husaynis a kind of hereditary aristocracy. This aristocratic status was won with religious respectability and a prestigious lineage. Furthermore, families such as the Husaynis augmented their power by establishing alliances with the military chieftains (aghawat) whose power was based on clientele and the control of suburban quarters and the grain trade that passed through them.

THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL BASIS

But prestige, alliances and connections were not enough to sustain the clan as a political force; they also needed financial resources. Most of these resources came with the appointments rather than ensuring them. The tax-farming system in the Ottoman Empire was such that it enabled the notables both to be enriched by and to accumulate political power. In a way, it was an alternative to the European banking system. As Sevket Pamuk explains:

While loans to kings, princes and governments were part of the regular business of European banking houses in the late medieval and early modern periods, in the Islamic world advances of cash to the rulers and the public treasury were handled differently. They took the form of tax-farming arrangements in which individuals possessing liquid capital assets advanced cash to the government in return for the right to farm the taxes of a given region or fiscal unit for a fixed period.10

At first this right was given for a year to three years, but during financial crises the tendency was to grant it for longer periods. The Ottoman Empire relied on tax-farming for urban taxes in particular, and hence the importance of notables who could serve as tax collectors. A different system was at work in the rural areas until the sixteenth century, but it was replaced by tax-farming thereafter, the concessions for which were auctioned in Istanbul.

Another source of income, and probably the most profitable one, was the ability of the notables to benefit from supervising, and later on breaking up, religious endowments – the awqaf (plural of waqf).

Before the emergence of municipal services, the authorities attended to the essential needs of the urban population through the waqf, the source for funding the restoration and maintenance of religious buildings and centers, educational systems and social services. Moreover, the waqf financed the expansion of infrastructure, the construction of bridges and the introduction of more systematic water supplies to the cities. The waqf was not invented by the Ottomans but was used more extensively by them as the best means of catering to the urban society’s concerns and requirements.11

Usually, Ottoman officials such as local governors founded the awqaf and appointed notables to look after them (as mutawallis and nazirs). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Husaynis established three awqaf of their own, while others of the family were appointed as mutawallis and nazirs, which meant the family as a whole became the beneficiary of the waqf.12 Gabriel Baer, who investigated the period from 1790 to 1801, discovered that the Husaynis had a larger share than any other group in founding new awqaf and in being appointed mutawallis (one third of the former and half of the latter).13

Awqaf that were endowed by the state for public services included profitable assets such as muzara’ fields (lands cultivated on a permanent basis), the total cultivated lands of several villages, factories, workshops, etc. Out of the profits salaries were paid. Sons of the notable families in Jerusalem were already receiving generous allowances from the profits of the awqaf in the early nineteenth century. Among them were the Husaynis, who were given the title wujah-i-murtazaqa (those who benefit most in several lists of awqaf). But they were not the only ones; they had to compete with many other families. There were about 1,000 to 1,500 notables in Jerusalem at the end of the eighteenth century, and they were about 20 percent of the overall population of several thousand. (Figures are not easily attainable for that period, and there is no room here to enter the debate about them.) Their high proportion within the overall Muslim community explains why they were so numerous among those enjoying the profits of the awqaf.14

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Ottoman central government found they could use the awqaf to reward families who cooperated with them.15 Supervision at the beginning of the nineteenth century was lax, and therefore families could expand their financial benefits from the endowments, which in principle were meant to serve the public. One imperial decree, a firman from 17 April 1797, decries the excessive number of beneficiaries drawing on these sources without the sultan’s permission, which led to growing debts that disabled the proper functioning of the endowed institutions.16

Inclusion on such a list required authorization from either the governors of the province or the city – or those who represented them: the supreme qadi (Islamic judge) in the region, the qadi of Jerusalem or his deputy. This explains the networking a notable family needed to do to sustain its economic prosperity. In the eighteenth century, an innovation was introduced: the beneficiary documents could be passed to the next of kin, a fact that expanded the lists and overburdened the debts of the awqaf. The notables themselves approached the governor from time to time and asked him to limit the lists so as to ensure smoother operations in the field of charity and aid to the poor.17 Of course, they made this request without giving up their own privileged positions.

In 1777, after a period of political upheaval, the central government transferred the right to grant beneficiary status exclusively to the Ottoman officials dealing with the finances of the empire. The ministry was ordered to consider further documents only on a purely economic basis. There was worse to come. The move annulled past documents, which generated a strong protest and a demand to return the old system. The outcry worked, and the old system was reinstated.18

The waqf became a particularly profitable asset in the beginning of the nineteenth century when it was broken up. Gaining control of public waqf domains and making them a family’s own private property was legal. Some cases were sanctioned by the local qadi and the properties registered in the sijjilat as privately owned land. Alongside the Khalidis, Nammaris, Nusaybas and al-Dajanis, the Husaynis were the most important family to amass wealth in such a way. These families held high posts in the waqf administration and in the Shari‘a judicial system and other Islamic institutions, so they exploited their economic power. But there were those who truly meant to help develop an endowment, and thus they re-endowed their investments.

This redistribution was executed in more than one way. The most common was followed by the deterioration of the asset so that it could be dismembered in a long-term, or perpetual, lease. This was a down payment of a lump sum by the tenant to cover the debt owed by the waqf, or from expenses on repairs and restoration in the form of long-term (90-year) leases at a very low rent. Transactions of this and similar kinds enriched the Husaynis considerably in the early nineteenth century.19

Assets that were not leased or dismembered still benefited the Husaynis. Being a mutawalli of other people’s endowments promised the family a large share in those assets, as well as a prestigious position in society.20 Again, research shows that for the first part of the nineteenth century, the Husaynis had a proportionately larger share in transactions involving endowments.

Apart from the waqf, the urban notables of Palestine also relied on the rural economy to thrive. In the nineteenth century, Palestine was a largely rural country, and revenues were directly connected to agriculture. Through the process of centralization that characterized the Tanzimat period, power shifted from rural lords to urban notables such as the Husaynis. Before the Tanzimat, the lords of the Palestinian hills owned a large share of the rural hinterland and received a considerable share of the land taxes and custom posts. These assets were now transferred to the urban elite.21

But generally speaking, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Jerusalem was not very important to the Palestinian economy either as a trading center or in its commercial activity. It was less its connection to the land and much more its holiness that provided income for many in the city, as did the frequent pilgrimages.22

Matters changed somewhat with the promulgation of the Land Law of 1858, which transformed the basis for landownership in the empire. The law required the registration and categorization of land for the sake of greater taxation. The Husaynis acquired land in many areas and became one of the leading landowning families. (However, since it took time for the Land Law to be applied in Jerusalem, the initiatives of the family occurred later on.)23

The sources of power varied with time. Once they held power, they found ways of maintaining it. By the time the Husaynis were both a religious and landowning elite, their fortified position in society was reflected in the educational orientation they chose for their children, who during the nineteenth century were sent to Ottoman professional schools to compete for places in Ottoman governmental service.

But while the nineteenth century brought with it new sources of power, it also set in motion processes that limited the notables’ influence in society. During their rule (1831–40), the Egyptians tried to overcome local independence, establish a centralized government and promote economic development. The Egyptian rulers tried to disarm the local population and introduced conscription, forced labor and new head taxes, as well as economic monopolies. The position of the notables was challenged again by the Ottoman programs of centralization, the Tanzimat.

When the Ottomans returned to Syria in 1840, they introduced some reforms that weakened the family Husayni to fulfill the reformers’ wish to centralize power, eliminate intermediary notables and mobilize mass support for the state. The family was also negatively affected by central authorities’ drive to secularize the judicial system and to introduce formal equality between Muslims and non-Muslims. However, they benefited from the local and municipal councils that were created to counterbalance local governors – councils within which they enjoyed important fiscal and administrative powers.24

With the advent of the age of nationalism, social standing no longer ensured the maintenance of financial and economic gains. Family wealth was now also part of the nation.

THE POLITICS OF NATIONALISM

This book tries to avoid the conventional school of thought that views nationalism as merely a product of modernization with a clear date and location of origin. Lebanon is typically singled out as the cradle of Arab nationalism, which is seen as an influential concept early on that then moved from Beirut to Jerusalem via Damascus.25

This is, of course, only one possible way of looking at it. Relying on more updated theoretical analysis of the phenomenon that has inspired a few intriguing volumes on Arab nationalism, this book treats the emergence of a nationalist point of view as a much more enigmatic subject. It examines nationalism before it became such a powerful feature dominating life in Palestine and Israel in the second half of the twentieth century – a period that is beyond the historical scope of this work.

The theoretical literature views nationalism in various contradictory ways: as an ideology, a product of the imagination, a cultural product or an act of social engineering. But there is a common thread running through recent critiques of nationalism. National identity, whether imagined, engineered or manipulated, is shown to be a recent human invention born of the integration of conflicting ethnic or cultural identities or the disintegration of such identities. This is the process described here.

Nationalism appears in this book as a modern invention that provides a new axis of social and political inclusion and exclusion that is neither organic nor natural. An artificial identification emerged, as in the case of the last years of Turkish rule, amongst those who belonged to the nation and more importantly amongst those who were excluded from it.

Late in the life of the Husaynis as notables of nationalism, Zionism came along and started a process that caused the Palestinians to construct an ‘other’ to their newly born national identity, an ‘other’ that became crucial to the formation of their national self. Hence, as is shown in the book, a Zionist threat was necessary to clarifying the uniqueness of the Palestinian national experience within the overall Arab one. But Zionism was not necessary for the emergence of such nationalism.

This book illustrates how national identity demands the subordination of other identities – communal, religious, ethnic, etc. This subjugation defines the parameters of ‘otherness’ and the degree to which it is constituted as a source of menace to the prevalent or hegemonic identity. The Husaynis followed through to the end of this process and in so doing delayed this subjugation – a disaster in the face of Zionism but a potential blessing for those who wished Palestine to continue benefiting from the more cosmopolitical and pluralist air of the previous Ottoman era.

SOURCES

Since the Husayni family was an integral part of local government, its political history can be traced with the help of the sijjilat, the records of the Shari‘a court in Jerusalem. This is a useful source for many who research Jerusalem’s history in the nineteenth century. The sijjil in Jerusalem is still kept in the storeroom of the Shari‘a court, and it covers the period from 936 to 1948. Like many other scholars much more experienced in using this type of source, I was fortunate to be able to see them with the help of the loyal staff of the Haram al-Sharif.

Reports by European diplomats and travelers were another important source. Albert Hourani believed the diplomats to be more reliable than the travelers.26 But in the context of our subject, some travelers’ reports seemed to be more trustworthy than the diplomats’ summaries, such as the ones sent by the British consul in Jerusalem, James Finn, in the mid-nineteenth century. These sources served me well into the mandatory period and provided depth that drier sources lacked.

Palestinian biographical and autobiographical works complemented the very thorough archival material found in both the Public Record Office and the Central Zionist Archives. Together these sources helped me to reconstruct the mandatory period. I also relied on the the valuable and amazingly vivid memories of Amina al-Husayni and other family members who recall this period.

The Arab Studies Society, which was headed by Faysal al-Husayni for many years, hosts a small family archive. I was fortunate enough to be helped by Faysal al-Husayni and Dr Budeiri, the chief librarian, with the materials present there (mainly secondary sources that relate to the family, as well as some letters and documents).

I also used quite a few sources in Hebrew – mainly secondary historiographical works that are unavailable in English. This may seem strange since this work seeks to challenge the scholarly and popular narrative common to most Israeli historiographies. The reason I used these sources is that industrious Israeli scholars have mined, and continue to mine, this relevant archival material in a systematic and admirable way – though their conclusions and interpretations follow the Zionist metanarrative very closely. Hence, while there are many references in this work to the empirical data they gathered, the plot woven here seriously challenges many of their conclusions and ideological assumptions.

Prologue

In the middle of the night between 28 and 29 October 1705, Muhammad ibn-Mustafa al-Husayni al-Wafa’i, naqib al-ashraf of Jerusalem, fled the holy city. (The naqib was the head of the families who claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad in the city of Jerusalem, and his position was one of the highest to which a local could aspire in the Ottoman Empire.) The naqib and a group of his followers opened the Nablus Gate in the wall of the Old City and fled under cover of darkness to the Mount of Olives. Halfway up the hillside they met other rebels who had come out of the city by way of the Mughrabi Gate. By daybreak, the rumor had spread throughout the city: the great uprising against the representatives of Ottoman rule had been crushed.

Though the revolt did not break out openly until May 1703, worrying information had been reaching the court of Sultan Mustafa II since early 1702. Ever since a new ruler was appointed the previous year, Jerusalem had been in turmoil – not only the city but also the nearby districts of Gaza and Nablus. The new governor was sent to collect taxes more efficiently.1 The Porte hoped that this would serve as an example to others, showing that the empire was still the mighty force that made Europe tremble – despite its unprecedented losses to Europe at the end of the seventeenth century – and was respected by its multitudinous subjects.

The new ruler brought with him extra troops to help him enforce the new collection. Any attempt to avoid paying taxes was dealt with by the governor’s troops at once. The troops, however, were not content to collect the due tax, and so they also periodically robbed the citizens. Any failure to pay the demanded tax was punished with a severe fine, and the general burden of taxation increased. The combination of taxation and looting was enough to drive the inhabitants to the verge of an uprising.

In May 1703, the burden of taxation and the savagery of the governor’s emissaries the year before had provoked general resistance, which intensified with the imminent arrival of the tax gatherers in the spring. Led by two young and inexperienced notables, a revolt broke out that was unique in the history of the district of Jerusalem in that it allied peasants and Bedouins with dignitaries and notables. The revolt went on for two and a half years (1703–5), centered around the mosque of al-Aqsa and the citadel. The governor’s limited troops were unable to subdue the determined rebels, and the naqib became the city’s de facto ruler.2

Inside the beleaguered citadel, the qadi of Jerusalem breathed a sigh of relief once the revolt had ended. One of the worst years of his life had drawn to a close – or so he hoped. He had come to the city from Istanbul towards the end of the previous year, on a mission that had filled him with anxiety before he even sailed into the Port of Jaffa. He had been appointed to represent the sultan’s law and order in a city dominated by the naqib and his cohorts, who were rebelling against Ottoman rule. The naqib received him courteously, but in effect confined him to the citadel, along with other government officials. Now at last the qadi might be able to administer the holy city in accordance with the Shari‘a, and perhaps win the sultan’s approval, as well as a more exalted post closer to his home in Istanbul.

As soon as he heard that the naqib had fled, the qadi ordered the drawbridge linking the citadel with the city wall to be lowered. The bridge had been raised from the start of the revolt, for fear of attack by the populace. Now the qadi crossed the moat with ostentatious ceremony, on his way to the fortress commander. On his left and right, evidence of Istanbul’s claim to sovereignty over Jerusalem was displayed in the form of engraved plaques noting the contributions made by the sultans through the ages to the city’s fortification. The most prominent plaque, the one over the fortress gate commemorating the building of the fortress by Sultan Suleiman I in 1531, was a reminder that the qadi represented the power that had ruled Jerusalem for more than a century and a half. The qadi hastened to consult the fortress commander about whom they would recommend to Istanbul to be the new naqib of Jerusalem. Walking confidently down the path from the city wall to the tower, he no doubt recollected the stirring events of the naqib’s revolt.

The qadi went to the Dome of the Rock, where he was met by the commander and the notables of the city. Before the meeting started, the qadi had the uncomfortable thought that most of his predecessors had been killed by rebels. And no wonder – the qadi was always the most tangible symbol of the sultan’s rule, for better or worse. Those qadis who survived were forced to obey the will of the mob rather than God’s holy law. He was determined to recommend to the authorities in Istanbul that the next naqib be someone loyal to the sultan’s representatives, and certainly someone who had his personal approval.

Many of the city’s notables had already turned against the rebellious naqib a year earlier, when they heard that the sultan was sending a large army to suppress the revolt. The naqib did not hesitate to confront this loyalist camp and fought a bloody battle against it in the city in 1704. The climax of the confrontation, involving many combatants, took place in the Bab al-Huta quarter, in the northern end of the Old City. By the time it was over, corpses littered the narrow, crowded alleys of the quarter that was named after the Sinners’ Gate, through which prayerful penitents entered. After this civil war many abandoned the naqib’s camp and joined the beleaguered faction in the citadel, who were waiting for the sultan’s army. The rebellious naqib chose to flee the city before the arrival of the imperial army.

A representative of that army, which was still a few days’ journey from the city, took part in the meeting. He brought the qadi greetings from the commander of the dispatched force and congratulated him on his resolute stand in the besieged citadel. Then the qadi reported that he was about to recommend that Istanbul appoint Muhib al-Din Effendi, of the Ghudayya clan (later to be known as the Husayni family), as the next naqib. He explained that, unlike the naqib who had fled, Muhib al-Din had been loyal to the government from the start of the uprising. In actual fact, Muhib al-Din had at first contemplated joining the rebels, but at this time he could certainly be counted among the loyalists, rather than the opponents of the sultan’s rule.

In the days that followed, the notables gave much thought to the reversals among the ruling officials. Now they were free to indulge in the pleasures of the hammamat (the baths), which they had been deprived of for some time. Most of them favored the Hammam al-Sultan, on the corner of al-Wadi (Valley) Street, which is also one of the first Stations of the Cross. There, amid the scent of rose water and the aroma of coffee wafting from the loaded trays of sweetmeats, they discussed the vicissitudes of their times, continuing their talk long into the night in the city’s cafes. The poets sang the praises of the new naqib and speculated about the future in between puffs of their nargilehs. These were the customary ways of the notables of Jerusalem, which Muslim travelers described as a lively city, quite unlike the picture that would be drawn by many Christian travelers, among them Gustave Flaubert and Mark Twain, who advanced the myth of the empty land and the desolate city.3

This was the city in which the Ghudayyas, the family of the fortunate Muhib al-Din, had resided for four centuries. The high points of life in Jerusalem, for them as for other notable families, were the mawlid – the religious festivals – weddings and births, and the occasional appearance of famous Muslim travelers, who were admired for their great learning in religion and the sciences as much as for their literary style. At their house – which at least one manuscript describes as a ‘palace’, so impressed was the visitor – the Ghudayyas entertained some of the great men of their era.4

But nothing was as momentous as the day of Muhib al-Din’s appointment, which in all likelihood was marked by a great feast. If so, it must have been attended by all the notables, who doubtless discussed the division of the spoils. The Ottoman authorities had expropriated the estate of the fugitive naqib and were about to distribute it to the loyal notables. The lion’s share was sure to be given to the two branches of the Ghudayya clan – the family of the new naqib and that of his cousin Abdullah, who had for years held the post of sheikh al-haram (sheikh of the Jerusalem holy sanctuary). Abdullah was greatly admired in the city for his work and his great learning in theology and i’lm al-fiqh, the Islamic religious precepts. But though his father had been naqib al-ashraf, he himself did not win the post and had to be content with being sheikh al-haram.5

We focus on Abdullah al-Ghudayya because his son Abd al-Latif is the central figure of the present story, a story that begins in 1703 and ends in our time and one that may indeed continue so long as the family is represented in the political life of Jerusalem and of the surrounding country, Palestine.

As far as we know, Abd al-Latif’s youth was uneventful, and he makes a rare appearance in the writing of a Sufi traveler, Mustafa Ibn Kamil al-Bakhri, who visited the city quite often.6 On his visits, al-Bakhri stayed near the mosque of al-Aqsa, where he settled for long spells after his second visit to the city in 1710. It seems that Abd al-Latif and al-Bakhri first met in 1724 at one of the city gates where al-Bakhri, about to enter, was reading the Fatiha before passing through, as was customary in those days. Having read the opening verses of the Qur’an, he changed his rich traveling apparel for the simple garments of purity, expressive of the visitor’s reverence for the city’s sanctity.

The naqib was welcomed by the Ghudayyas and by sheikh al-haram Abdullah and his son Abd al-Latif. After praying together and exchanging lengthy blessings, the august company walked through the city, composing a qasida (a poem in the classical style) at every noted site:

In the name of God, if you meet us, we shall tell you it is the day of Jerusalem. Together let us go to this city and visit it. The Good will be with us forever.7

Each time al-Bakhri returned to Jerusalem he brought books from his library in Damascus, thereby enriching the lives of his companions in Jerusalem. His visits also had a certain missionary quality. Al-Bakhri was a member of the mystic Sufi Kheloti order, which he would eventually head. But it seems that his hosts were more impressed by the order’s ostentatious self-mortification and accompanying ceremonies than by its theological message of approaching God via Muslim mysticism.8 Members of the family were entranced by the spectacular exercises and the dancing in a circle that culminated in intense excitement. Al-Bakhri never arrived on his own: as a man of high position, he was always surrounded by an entourage, and his frequent visits demonstrated the great importance of Jerusalem in the Muslim world of the early eighteenth century.

Hosts and guest alike passed the time discussing the mysteries, showing off their abilities as religious mystics. Al-Bakhri was deeply influenced by one of the great medieval Sufi philosophers, Ibn al-Arabi. Al-Arabi had written about the creation of the world and of understanding it, and consequently al-Bakhri wrote a good deal about such subjects. It is possible that not only members of the religious elite took part in such gatherings but also others such as the sheikh al-tujjar, the leader of the city’s merchants.9 During his visit, al-Bakhri gave the customary guest lecture; he liked to quote from ‘The Praises of Jerusalem’ – the literature lauding the city, which had grown following the Crusades. He also visited the graves of holy men, among them that of Nabi Musa (the Prophet Moses) near Jericho, where he spent the week of festivities in the prophet’s honor.

The Ghudayyas took to al-Bakhri. He was invited to be the guest of honor at the dinner celebrating Mawlid al-Nabi (the Prophet’s birth), and they offered him a chair in the courtyard of al-Aqsa mosque, where most of the guests reclined on cushions on the ground. The public dinner was a widely attended occasion in which all walks of life took part: the rich and the poor, the learned and the ignorant. In a travelogue he wrote after an earlier visit in 1690, al-Bakhri expressed his wonder at seeing that among the throng ‘there were also veiled women in the corner of the mosque, and with them young and small girls’. The muezzins trilled the verses. Servants of the haram circulated through the multitude, offering sweets and fragrant pastries and finger bowls of rose water for the guests to rinse their sticky hands in, and at last the crowd dispersed, well-fed and contented.10

The years that followed al-Bakhri’s visit were disappointing for the Ghudayyas. During the 1730s, the key posts in the city were given to other families. The Alami clan, for example, won a number of lucrative positions at the expense of the Ghudayyas, causing the rivalry between the two clans to continue for some time. Like the Ghudayyas, the Alamis had made good use of the naqib’s revolt in the early years of the century, and persuasion combined with money won them the position of mufti, which the Ghudayyas had coveted.

The mufti was a state official who wrote opinions (fatwas) on legal subjects for judges and common believers. Some of his opinions became binding precedents. He also belonged to an Ottoman hierarchy that was supervised by the mufti of Istanbul, who had the power to appoint and dismiss local muftis around the empire.

But this was a temporary decline – Abd al-Latif’s family would later recover the mufti’s post, and the three most important positions held by local personages under Ottoman rule would be theirs: naqib al-ashraf, mufti and sheikh al-haram. No wonder they became the most important family in Jerusalem and perhaps in all of Palestine.

For a short while it looked as if all this glory would fall to the Alamis. In January 1733, when Muhib al-Din of the Ghudayyas died and his son Amin was appointed in his place as naqib al-ashraf of Jerusalem, the Alamis moved into action. Amin was a pleasant man, but even his family recognized that he did not have the necessary qualities to serve as naqib. As soon as it became known that he had failed to settle a feud between two city families, the Alamis began to agitate for the post. They bribed the Grand Vizier and the governor of Damascus, and with their support obtained it.

It took Abd al-Latif twelve years of continuous effort to wrest the prestigious position from his rivals. Bribery, intrigue and considerable personal charisma restored the Ghudayyas to the apex of the local hierarchy. Having won this position, Abd al-Latif launched a successful dynasty that would drop the name ‘Ghudayya’ and adopt that of the fugitive naqib – ‘al-Husayni’. This dynasty would lead Palestinian society for the next two and a half centuries, up to the present day.

Appropriating the name and lineage of another clan requires great ingenuity and the ability to exploit uncertain political circumstances. It is unclear exactly when this happened, but thanks to Adel Mana’a we do have the genealogy that was used to create the family’s new identity. It is hard to determine whether it was a deliberate takeover of another family’s lineage, as one would be inclined to imagine, or an error due to the families having an ancestor with the same name back in the seventeenth century. The rebellious naqib al-ashraf was the head of the Wafa’i Husaynis, and he had a great-grandfather by the name of Abd al-Kader ibn al-Karim al-Din. The Ghudayyas also had a great-grandfather by that name.

The Ghudayyas’ lineage was fairly lackluster compared to that of the Wafa’i Husayni. The latter family arrived in Jerusalem in the early fourteenth century, with a family tree stretching back to the Prophet Muhammad – to be precise, to Hussein, the son of Ali, husband of the Prophet’s daughter Fatima. A direct line of succession leads from Hussein to one Muhammad Badr al-Din, who made his way in the fourteenth century from the Arabian Peninsula to Jerusalem and built a house in Wadi al-Nusur on the city’s outskirts.

The Wafa’i Husaynis appear in records from the sixteenth century onwards, and they are certainly not the forefathers of today’s Husaynis but rather their adoptive ancestors. Another theory ascribes to them a different, anonymous ancestry. There evidently was a hiatus in the grand ‘family history’ that was doubtless quoted and repeated whenever the family’s fortunes either faltered or rose to new heights.11 The adoption of the new family name was followed by closer ties with Jerusalem families of more esteemed lineage. Daughters were married to the sons of the al-Khalidi and Jarallah families, considered to be the noblest in the city. In this way the family kept its position in the front rank of the city’s notables, even if it did not always retain all three leading posts in Jerusalem.

It appears that the name change had already taken place by the 1770s, when Abd al-Latif was in his forties. Documents show that by that time he was already a respected figure – rais al-Quds ayn aayanuha (the leader of Jerusalem and its notables), as he was dubbed by contemporary historian al-Muradi. Abd al-Latif was famous for his generosity and modesty. And though al-Muradi lavished such praise on almost every notable, in this case he offered various testimonies to back it up. Abd al-Latif served his guests with his own hands, reported the amazed al-Muradi, ‘and always smiled at his children and preferred the poor over the rich’. He was renowned beyond the confines of the city as one who provided food for pilgrims and indigent visitors. The poets of the time, al-Muradi goes on to say, sang his praises in their poems.12

We have a slightly different version of the story about the name. Butrus Abu-Manneh proposes opening the narrative not with the Ghudayya clan but with Abd al-Latif’s father, the scion of an important family whose name is unknown, because prior to the eighteenth century, Abu-Manneh claims, people did not use surnames.13

Members of the family, however, have asked that we begin their history with the Prophet Muhammad, since the link between the Husaynis and the Prophet’s family was the basis for their claim to a senior position in Palestine – and who is to say that this claim is or is not valid? Max Weber argues that the identity of a given organization is the sum of its subjective and objective definitions. During most of the period covered in this account, the local population accepted the Husaynis’ claim to notability, and this acceptance was used to advance its status. Towards the end of the period, however, the situation changed – by the late Ottoman era, and a fortiori in our time, a family’s lineage is of secondary importance.

We cannot tell if the Ghudayyas’ claim of having descended from the Wafa’i family, whose positions they inherited, was a deliberate act. Be that as it may, it was a very proud claim. The Wafa’is owned, among other properties, the zawiyya that bore their name: al zawiyya al-wafa’iyya. This was a room, usually in the corner of a mosque, for the accommodation of the dervishes, who with their unkempt beards and worn sandals slept on straw mats and subsisted on charity. The Wafa’i zawiyya was exceptionally highly regarded, because it was also known as ‘dar al-Mua’wiyya’, after the khalif al-Mua’wiyya, who had stayed there with his daughter Fatima. A stone memorial engraved with her name still stands there. It was in this zawiyya that the Wafa’i Sufi order came into being.14

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, the various accounts converge into one that describes the rise of the Husaynis in parallel with the decreasing power of the Ottoman center. This enabled the family not only to win the most important posts in the city but also to wield influence in the religious and secular centers of power. The post of the naqib was theirs for a while, and the function itself grew in importance in the latter half of the eighteenth century; it was equal and in certain cases, as we shall see in our narrative, even greater than that of Istanbul’s official representatives. By that time, the Husaynis were unquestionably one of the leading notable families together with the al-Khalidis, the Jarallahs, the al-Jama’is and others. But the post of the naqib was not assured, and the Husaynis would lose it from time to time. Nevertheless, in any history of Jerusalem from the eighteenth century onward, they figure more centrally than any other family or clan.15

CHAPTER 1

The Making of a Family

From al-Ghudayya to al-Husayni

On the first day of the year 1765, Mehmet Aga, the chief eunuch in the harem of the sultan, was awakened by a strong but pleasant odor. It was the scent of soap, familiar to him ever since that ‘Arab Abd al-Latif’ (Abd al-Latif II) was appointed naqib al-ashraf in Jerusalem. The latter had a small soap manufactory in Jerusalem, and many in the palace had become partial to its soaps and vials of rose water. The chief eunuch was especially fond of soaking in a rose water bath, but his supply had recently run out. Now he got out of bed as briskly as his great bulk allowed and prepared to meet Abd al-Latif’s emissaries. He gave his sleeping servant, a young black eunuch recently arrived from Egypt, a little kick to wake him and sent him to the major–domo to help him sort out the presents intended for the various dignitaries who were regular recipients of Abd al-Latif’s largesse.1

The majordomo found the delegation from Jerusalem standing beside the guardhouse that had sprung up near the eunuchs’ quarters and watching open-mouthed as builders and masons completed the conversion of the harem from a traditional Ottoman structure into a baroque-rococo one.2

Abd al-Latif’s son Abdullah was the delegation’s leader. After the usual greetings, he addressed the chief eunuch as follows: ‘We urge our glorious son, Mehmet Aga, to do his utmost to distribute these gifts in accordance with our wishes, and may Allah prolong his days. To our benefactor, sheikh al-islam, a chest of soap, a jar of rose water and six head-coverings …’3

The list went on: former chief qadis, past and present naqibs al-ashraf of Istanbul, all received one or two fragrant chests and soft linen caps with the dignitaries’ names embroidered on them by daughters of the family. As on previous occasions, Mehmet was asked to obtain receipts showing that the gifts had reached their destinations. The list was usually made up of eighteen of the imperial capital’s dignitaries. Two chests were always assigned to the sheikh al-islam (who appointed local notables to the highest religious posts) to make sure he remembered Abd al-Latif’s four sons and would obtain plum positions for them in the city’s religious hierarchy.

Abdullah spent several days in the bustling capital and called on Zayn al-Abidin, Istanbul’s naqib al-ashraf, an exalted official empowered to appoint and discharge any naqib al-ashraf in the provincial capitals throughout the empire. Zayn al-Abidin assured Abdullah that the niqaba – the post of naqib al-ashraf of Jerusalem – would remain in the family, or, more precisely, remain his.4 The authorities also confirmed Abdullah in his post as supervisor of the sanctuary of Nabi Musa.

This time the mission was driven by some urgency: the governor of Damascus harassed the family by threatening to pass the niqaba to the Alami family. As noted before, ever since the appointment of Muhib al-Din al-Ghudayya to the post of mufti, the Alamis had coveted the post and had actually filled it for a while.

ABD AL-LATIF, FOUNDER OF THE NEW FAMILY

But all that was in the past, and in 1765 Abdullah was thinking about the future. Would he be able to repeat his father’s achievements?, he wondered.

Zayn al-Abidin clearly remembered Abdullah’s father. Al-Qudsi – ‘the Jerusalemite’ – was the nickname of the notable who sent him chests of fragrant soaps, sweet rose water and exquisite caps almost every year. The first such delivery arrived in 1740, accompanied by a letter begging for the post of naqib to be restored to the Ghudayyas. The letter vilified not only the Alamis but also their allies the Jarallahs, likewise one of the grandest families in the city. With amazing boldness, Abd al-Latif asked not only to have the post of naqib restored to him but also his father’s old post of