7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

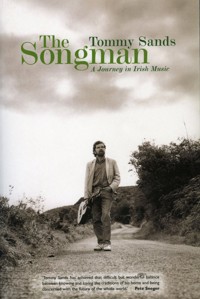

With a Fenian fiddle in one ear and an Orange drum in the other', singer Tommy Sands was reared in the foothills of the Mourne mountains, where he still lives. As a child, he was immersed in folk music - his father played the fiddle, his mother the accordion. The kitchen was where Protestant and Catholic farmers alike would gather for songs and storytelling at the end of a day's harvesting. During the sixties and seventies Tommy was chief songwriter for The Sands Family, who played wherever they were welcome, from local wakes and weddings to New York's Carnegie Hall; his songs have been recorded by Joan Baez, Dolores Keane, Dick Gaughan and The Dubliners. He tells of his family's traditional way of life; of the turbulent days of the civil rights movement; The Bothy Band brawling in Brittany; encounters with Alan Stivell, Mary O'Hara and Pete Seeger; Ian Paisley on his radio show Country Céilí; and a 'defining moment' during the Good Friday Agreement talks, when he organized an impromptu performance with children and Lambeg drummers. The Songman is a memoir replete with warmth and wit. 'Tommy Sands' words fairly 'freewheel down the hill' but they also have a great zest to 'sow the seeds of justice'. You feel you can trust the singer as well as the song.' - Seamus Heaney 'Tommy Sands has achieved that difficult but wonderful balance between knowing and loving the traditions of his home as well as being concerned with the future of the whole world.' - Pete Seeger

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

For my parents and Dino

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

1 The Songman

2 Between Sleeping and Waking

3 Before Books

4 Bad Boys and Good Uncles

5 Religious Persuasion

6 Changing Times

7 A Feast between Politics

8 Record Time

9 Civil Rights

10 Walking On

11 Vying for Light

12 All the Little Children

13 Let Ye All Be Irish Tonight

14 Beyond the Curtain

15 There Were Roses

16 Tour de France

17 Dino

18 Country Céilí

19 Plaisir d’Amour

20 Humpty Dumpty

21 On the Run

22 The Man from God Knows Where

23 14,000 Miles

24 Lessons in Moscow

25 Long Live the Chief

26 The Fall of the Wall

27 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star

28 Unsung Heroes and Unwritten Songs

29 The Music of Healing and the Citizens’ Assembly

30 Goodbye Love, There’s No One Leaving

31 Good Friday

Index

Copyright

List of Illustrations

The Connolly Clan, Burren, 1932

Eoghain Smith, my mother’s grand-uncle on concertina, c. 1900

My father’s family, 1924

Mother, 1939

I stood as a marker for the ‘corn fiddler’

Father and Mother, 1959

Tommy and Hugh, aged 8 and 9

Fr Hugh and Fr Tom

The Thresher

The hay, 1958

Thatching the stack

The Sands, 1960

The Sands Family, 1966

In The Ship

The Sands Family in the Long Field

Sampling the new apple juice

On the banjo in Carlow

Tommy Makem welcomes The Sands Family to New York, 1971

Interviewing Mike Flanagan, the last survivor of The Flanagan Brothers

With the Clancys – Paddy, Bobby and Tom

The Sands Family in Germany, 1974

Da and Ma on fiddle and box beside where the roses grew

Dino, 1975

Dino memorial concert, 1976

Archbishop Tomás Ó Fiaich

Catherine Bescond in Brittany, 1976

Our wedding, 1979

With Gary McMichael

With Catherine, Fionán and Moya

Tucson concert with Mick Moloney and Eileen Ivers

Pete Seeger with Moya and Fionán

With Tanya Vladimirsky in Moscow

The Chief, in Gorman’s, one for the road

With Eileen O’Casey and Catherine

Festival in East Berlin

Receiving a Doctor of Letters with Jill and Catherine

With Rubin Hurricane Carter

At Catherine Hammond’s wedding party in Belfast

Launching The Music of Healing

With Joan Baez and Robin Cook

At the ‘Talks’ with Gusty Spence

Celebrating hope in the great hall of Stormont after performances

Acknowledgments

Thanks to my parents and family, Catherine and children and a multitude of friends and relations whose story and stories knowingly or unknowingly touched and moved my own. Thanks to Jack L. Bacon, Sadbh Baxter, Hilary Bell, Barney and Marge Brady, Kerstin Caffo, Fil Campbell, Steve Cooney, Dominic Cunningham, Peter Emerson, Roy Garland, Bobbie Hanvey, Seamus Heaney, Phylis Jackson, all at Lilliput, Paul Lyle, Colum McCarthy, Frank McCourt, George MacDonald Fraser, Tom McFarland, Mark McLoughlin, Siegfried Maeker, Peter Makem, Mick Moloney, Tom Newman, Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, Annie Prince, Mary Rowley, Pete Seeger, Vedran Smailovic, Daragh Smyth, Marsha Swan, Robin Troup, Mike Wolke, and Itka Zygmuntowicz.

The SongmanA Journey in Irish Music

1

The Songman

‘Are you the son of the man that pulled my granny out of the coffin?’ The Royal Ulster Constable lowered his voice, and his Heckler and Koch automatic, for the question and then bent his ear round the car’s turned down window for an answer.

This was all I needed. I was already late. All the other questions had been easy. A child could have answered them.

‘What’s your name, sir?’

‘Tommy Sands,’ I’d replied.

My father used to say that any time he was called ‘sir’ he would cover his pockets for fear of being robbed. He had a deep suspicion of such niceties.

I reached for one of my passports. The British one.

‘That’s me,’ I said. ‘I’m coming from Rostrevor. And I’m going to Stormont,’ I added quickly, hoping to pre-empt the next two questions. It would save time, I thought, and police breath. And they were fairly safe answers too. Neither place would send the shivers up a lawman’s back.

‘And where are you coming from sir?’ he continued dutifully. The Law would take its own course and not be rushed.

‘Rostrevor,’ I said again resignedly, waiting for the next question with wearily rehearsed respect.

Satisfied that I had learned my lesson for the moment at least, he went on calmly. ‘And what takes you up to Stormont, sir?’

‘To sing,’ said I.

‘To sing?’ said he.

‘To sing,’ said I. ‘At the Talks. The Peace Talks.’

‘And have you permission?’ He asked, with a recharged interest.

‘I do,’ I said, trying to hurry things along. ‘From George Mitchell, the American man, the chairman of the Talks.’

He looked at me silently for several seconds before unleashing the final question, the answer to which he was now patiently waiting for. It was close to eleven o’clock on the morning of Holy Thursday 1998. I had to be at Stormont by twelve.

It wasn’t the first time, of course, that a roadblock had stood in the way of a performance. Back in the civil-rights days in the sixties it wasn’t unusual to be held up for hours, or for as long as it took for the concert or rally to be well and truly over by the time you got there. A sense of urgency, however, told me that today’s performance would be more important than most.

I had grown up singing at enough wakes, weddings and gatherings in my home townland of Ryan in County Down to realize that music is too valuable to be confined solely to concert stages. After the first lust for public recognition is sated, the musician feels ready to seek out the ‘real gig’. It can be in a prison or a school or an old folks’ home, or in the house of a neighbour when things are low and where the magic of music passes through performer and listener, easing the mind and the soul in a strange sacramental harmony.

The politicians of Northern Ireland were badly in need of some harmony. The negotiations taking place at Castle Buildings in Belfast had faltered, and this had been the toughest week of all. Some looked back to see where their followers were leading them; others looked ahead and pressed forward. We had condemned them in the past for not talking and it was no less important to applaud them now that the talking had begun. For years it had been like watching two buses meeting on a narrow bridge with neither driver wanting to give way for fear of letting his passengers down. It would only be when those passengers would slowly begin to rise and say, ‘Look, it’s all right, you can reverse a little, because we all want to go forward,’ that the scenery would ever change.

Outside, in the surrounding stillness, spring was silently intensifying the greenness of the grass and the orange of the dandelion and spreading blossoms on the Mourne hawthorn like Easter snow. Decaying smells of winter were yielding to the subtle spell of speedwell and robin-run-the-hedge, and the small birds of Ulster were tuning up for a song yet to be sung.

A bracing north breeze, laced with bitter memories, browsed the scattered remains of one of yesterday’s newspapers before brushing it gustfully round the black boots of the policeman. With a graceful kick, he sent the latest helping of media opinion up in the air. Headlines of hope and despair alternated in the tumbling wind. It was touch-and-go and the journalists were saying that anything could happen. Time was running out. There would be an agreement by Good Friday or there wouldn’t be an agreement at all.

When the Talks began in 1996, they had been met with a cautious optimism. Every news space seemed to be filled with hope and relief. But in no time the new-shounds were sniffing around for fresh stories to report. That’s their job. Peace meant less action, and less action meant less entertainment for the punters. How long can you hold a shot of calm sea and blue sky before your audience wants the thrill of a storm and your advertiser a new channel? On television it wasn’t long before it seemed that no one wanted the Talks to be happening at all. Everyone was up in arms about compromise, trickery and treachery. The viewing figures would be on the increase, sure enough, but just as surely the viewers’ hearts would be sinking.

The people I knew from both sides of the hedge in the hills and valleys around me and in the towns and villages before me were crying out for the politicians to carry on, but their voices were not being heard. People in search of peace seldom shout loudly. It was time now to gather their voices together and sing, to give a song to the six o’clock news, and to give the media its storm – a storm of peace for a change.

Carry on, carry on, you can hear the people singing,

Carry on, carry on, till peace will come again.

I had rehearsed the song the night before with Vedran Smailovic, a cellist from Sarajevo. He would be waiting for me now in Burren, just a few miles away in the home of my mother’s people, with a borrowed cello in a blue case. His own was lost in the rubble of his native city. Protestant and Catholic children from two schools in Dundrum would be travelling to Stormont as well, and my good friend Roy Arbuckle would be on the road from Derry, sporting the ultimate loyalist instrument, the Lambeg drum. The chorus was simple. Hopefully the television crews would pick it up, so that the people at home would hear their own message being broadcast and the politicians would be reassured that the passengers on the bus were behind them.

In the Bogside and the Waterside, in the Shankill and the Falls,

All around the hills of Ulster, you can hear them sing this song.

Carry on, carry on, you can hear the people singing,

Carry on, carry on, till peace will come again.

It had been a long struggle to reach this day. There had been much soul-searching and risk-taking. What would happen to the political life of Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble if he dared to sell short the unionist cause? We all remembered Brian Faulkner’s political collapse in 1974 after he reached an agreement at Sunningdale on behalf of unionism, with shades of compromise. And what would happen to Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams if he betrayed the ideals of Irish republicanism? The fate of Michael Collins was well known. He had been shot in 1922 during the Irish Civil War. Our song would have another view of betrayal.

Don’t betray your children’s birthright, that’s the right to stay alive,

For there is no greater treachery than to let your children die …

In the streets and schoolyards, at crossroads and village squares, at fairs and football matches, everyone was talking about the Talks. In churches, chapels, and meeting houses people were praying, and in mixed public houses drinkers who would usually avoid contentious issues were now openly discussing the negotiations at Castle Buildings. At last there was something everyone could agree on – the need to talk. The world’s media were gathering for the showdown of the century. The patience of people like Social Democratic and Labour Party leader John Hume, who had been attacked from all quarters for entering into a dialogue with Adams, was beginning to bear fruit. American President Bill Clinton was on the phone to Stormont every day. Bertie Ahern, the Irish Taoiseach, would be there, and British Prime Minister Tony Blair had arrived in Belfast to say that he felt the hand of history on his shoulder. I wanted to be there too, but there was a policeman’s ear in my car, still waiting for an answer, and I couldn’t move.

I don’t think I had ever been so close to a policeman before. I could see the harp and crown on his cap, emblems that weren’t traditionally the easiest of allies. ‘Hang all the harpers’ had been the order from Elizabeth i during her struggles to defeat the old Gaelic Order. What did this officer think of ‘peace-loving’ musicians kicking up trouble and change? Regardless of what permission I had from the top, right now this was the man who would make the decisions on the ground. How did he feel about all this talk about talk? What would happen if peace did suddenly break out? There were republican calls to disband the RUC as part of any new settlement. Why would a man in his position have any more enthusiasm for that than a turkey would have for Christmas? What about the overtime pay that would disappear? What about the mortgage for the new house?

His trained hearing seemed to suck all the sound from within the car, leaving an awkward silence. All I could hear was that high ringing tone that the souls in Purgatory send out to Catholics when they want prayed for. Since 95 per cent of the RUC was Protestant I assumed that this policeman wouldn’t hear or if he did, he wasn’t impressed – he was only interested in finding out whether my father had pulled his granny out of her coffin. He turned his head and looked into my eyes. Did he see the bitter eyes of a Catholic looking back, a man who hadn’t much faith in the police force? A force that upheld the laws of a state, whose ‘Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’ had discriminated against 40 per cent of the population because they were Catholic. A force that was used to put down a civil rights movement that had attempted to right those wrongs, thus igniting the violence that had held the North in its grip for thirty years. A force whose members colluded with loyalist paramilitaries to kill innocent Catholics. And did he see an incurable rebel whose people had been opposed to his country from its inception in 1921; whose tribe had silently supported the IRA, with its list of legitimate targets, which included policemen like himself? We may have been standing on the same ground, but in our heads did we live our lives in two different countries?

There was something familiar about this man. I tried to see him without his policeman’s cap. It was his eyes. Without warning his lips began to move. Suddenly he began to whisper the words of a song in a childlike voice:

It’s eleven by the clock and I’ve only on one sock

The bike’s punctured so you understand my rush

I’m for the town today, stand back and clear the way,

For I’ve got to catch that half-eleven bus.

I was taken by surprise, not only by a policeman uncharacteristically breaking into verse but by the song itself, which began to unravel half-forgotten memories. It was the first song I had ever written.

‘What comes after that?’ he said with a grin.

The traffic was piling up behind us.

My memory searched for the next verse.

Well, away I go at last and I’m moving pretty fast,

I’ve just passed Davy Wilson riding Flo,

Nora tells me from the gate, ‘Hurry up or you’ll be late,

For Tommy’s gone at least an hour ago.’

‘How do you know that song?’ I stared out at him, flabbergasted.

‘Because you sang it for me forty years ago,’ he said, ‘while we tied bands on corn stooks on the back hills of Turnavall. The Nora in the song was an old friend of my mother’s, and she still is, for she’s as alive and well today as ever she was.’

‘Yes, yes,’ I said, ‘for goodness’ sake, Nora Wilson. Many’s a time she lent me her green bike with the three speeds on it. Your name’s Ross. Ivan Ross,’ I stammered, with growing certainty. ‘We worked together as children during the harvest all those years ago. My God, how the time and times scatter people. You used to come out from Newry to visit your granny and your Uncle Jim. We must have been nine or ten.’

‘Remember tying the corn?’ He took up the story. ‘My fingers were full of thistles but you daren’t have stopped to pull them out or you were called an oul’ woman. You country people were a tough crowd. And you and your family were always singing and your da always playing tunes. I’ve followed your music ever since, on the television and the radio and all the rest. Do you mind the last time we met? Your da playing the fiddle at my granny’s wake?’

It was all coming back to me now – my father, his granny, the coffin … every toe-curling detail. We had gone to the house to play, but not before my father had paid a visit to the pub, ‘just for the one, to rosin the bow and graize the throat’. Then we headed for the wake, for they were waiting for him and for the fiddle too.

In Ireland music has always celebrated the happy times, but even more importantly it marked the sad times. Traditionally, at a wake or at a wedding (because sometimes that was sad as well, with a young bride leaving the family to set up a new home) crying women would be sent for. Their job was to keen (from Irish caoineadh, ‘lament’) and to get everyone in the house crying too. Musicians would have the same effect. They would play a lament to help people cry. These slow airs were not intended to make the listener sad but to draw the sadness out, so that the people could get back to the living and the dance of life. I suppose nowadays it’s the psychologists and counsellors, rather than keeners and musicians, who make a living drawing the sadness out of people.

I remembered now, right enough, when Elizabeth Maharg died, and my father landed at the wake, together with my brother Colum, my cousin Petesy on the Hill, and I. My father played a lament called ‘Dinnis O’Reilly’, and followed up with ‘William’s march’. Then he went over to the coffin and looked at the corpse.

‘You were one of the other sort, Bessie,’ he said, ‘but you were always a good neighbour to me. I’ll say a mouthful of prayers for your soul and if they do you no good, sure they’ll do you no harm.’

Down he went on one knee and in that position there certainly was no evidence of harm being done to anybody, living or dead. It was when he was getting up that the trouble started. With the bottles in him and the years on him, my poor father wasn’t the steadiest, and reaching out for support, didn’t he grab on to the side of the coffin.

‘Is that the time you’re talking about, Ivan?’

‘The very same,’ he said, ‘and if it wasn’t for the quick reflexes of your cousin with the big hands, she’d have been a goner.’

He was right. Petesy on the Hill, the goalkeeper for the local Saval football team, had jumped forward to save the day that night.

The constable’s face had slackened into a broad familiar smile. ‘But sure everyone understood and no remarks were passed, for we all appreciated the music and your da was a good man. They were the good times. That was before the Troubles,’ he added quietly.

‘Will this be the end of them, do you think?’ I gave him a direct look.

‘I hope so,’ he answered. ‘Good luck with the music today. I’m all behind you.’

‘I hope we meet again before another forty years have passed,’ I said. ‘I’d like to hear how you’ve got on.’

He reached out a hand and I couldn’t help noticing his fingernails, chewed to the quick. I tried to remember the last time I had shook hands with a policeman, and couldn’t. ‘I’d like to hear more about your life too and what makes you keep singing,’ he said, ‘Please write!’ He made no attempt to reveal his address and I made no attempt to ask for one. I thought I felt a strange reawakened pulse pass through our handshake, like a long-lost dance, shaking out sadness.

Then he moved away from the window, straightened up his gun and shouted to the policemen ahead. ‘It’s all right, boys, let him through. It’s the songman.’

2

Between Sleeping and Waking

The Golden Eye of God peeped over Slieve Donard and slowly, in its own good time, lit the small farms and fields of south Down in light green, soft yellow, bright orange, dark brown and a deep mysterious transparent grey. The sun didn’t rise too early in December, nor indeed did anyone else, for that matter, in that particular part of the country.

Auntie Maggie got up earlier than most that day. She had visitors. She opened the curtains and eyed the Irish Weekly the breadman had brought. It was lying stretched out and bedraggled on the sofa. She looked at the picture of the man standing on his head on the front page. It was Benito Mussolini hanging upside down in Italy. She turned it around to see how he looked standing up. He reminded her of old Doctor Taylor.

With a shiver, she separated the front and back pages from the rest of the paper, folded them twice, and began to twist them into a rope, like she was wringing out one of her brothers’ shirts. Then she worked the paper ringlet into a circle and set it down upon the cold grey ashes in the hearth. She noted how the ring of newspaper began to slowly unravel into a horseshoe when she let it go, and the man’s face seemed to slacken into a strange smile. She smiled back sourly. Auntie Maggie didn’t read, there was never anything in papers she needed to know, but that face reignited a spark of forgotten apprehension inside her. She had watched her own mother die in childbirth due to the neglect of old Doctor Taylor. She quickly moved on to the next two pages.

There was a photograph of a new group of people who were going to stop wars. They were called the United Nations. She thought they looked like the Burren Gaelic Athletic Association committee. The GAA was set up in 1884 to promote Irish sport and to stop faction fights between parishes. In the front row sat a man, arms folded, the spit of her brother James. James was chairman of the local committee. She smiled a different smile, and began twisting the pages again.

The Connolly Clan, Burren, 1932 (standing) Patrick, James, Peter, Katie, Bridie (my mother), Fr Tom, Maggie (sitting) my grandfather Eoghain Connolly, the poet

When all the paper was in the hearth, she placed small twigs on top, and then larger ones, and took a flame from the Sacred Heart lamp hanging on the wall above her head and set them alight. It was the first smoke to curl up a Burren chimney on the morning of 19 December 1945.

Then Auntie Maggie let out the hens.

‘Come on out now, like good hens, and I’ll know by your cackle if you’ve laid an egg.’

The two children of her youngest sister Bridie were at her heels. They loved boiled eggs.

After breakfast, Auntie Maggie made a startling announcement.

‘You’ll have a wee brother before the night,’ she whispered.

‘How do you know that?’ they asked in wonder.

‘It’s clear as day in those tea leaves,’ she said. ‘And his name will be Thomas.’

No one ever doubted Auntie Maggie. She had a way of knowing things long before they happened. She would even predict the day and date of her own death. But that would be many years later. Now was a time for celebrating life. The war was over. Hitler was dead. Mussolini too. And a lot of other people were dead as well, but the darkest nights would soon be gone, Christmas and New Year were just around the corner, and today a child would be born.

Eoghain Smith, my mother’s grand-uncle on concertina, c. 1900

It was still too early for Bridie to celebrate. She was the youngest of the Connolly family and the life and soul of every party. She had played camogie with Burren and acted in all the plays. She had inherited her talents on accordion and concertina from her grand-uncle Eoghain Smith and her love of words from her own father, Eoghain Connolly, the poet. Now she was waiting to go into the theatre in Rathfriland Hill Hospital in Newry. This would be her third Caesarean and the operation was scheduled for eleven. She had no way of knowing if it would be a boy or a girl. She only prayed that all would be well.

If the baby was a boy, she had decided to call it Michael Thomas – Michael, because Mick Sands was the name of her husband, and Thomas after her uncle, Whistling Tom Connolly, and her brother, Father Tom Connolly. Father Tom was coming home from the Philippines to do the christening. She had decided to ask her sister Maggie to be the baby’s godmother.

Mick Sands wasn’t celebrating either, at least not yet. He was six miles away, picking blue spuds at a brown pit in the townland of Ryan, where he had lived all his life. When he sold the spuds, the money would come in handy with the addition of a new baby in the family. Later in the day, he intended to celebrate in the usual way with Big Harry McManus and Wee Harry McManus, not for a day or two days but for the week his wife would be in Burren with the children and her own people. She would be well looked after there.

That evening in Tim Collins’ pub in Newry Big Harry shouted, ‘Turn that “Cruisin’ down the river” song down, Tim. I’m sick listening to it.’

‘You have to keep up with the times,’ Tim called from the bar. The song was the number one hit of the year.

‘I’ll sing you a song,’ said my father. ‘One that’ll be around when “Cruisin’ down the river” is as dry as a blind man’s buff.’

‘Is it a boy or a child?’ asked Wee Harry.

‘It’s neither,’ said the father of whatever it was, for that’s what he had just become.

‘What in the name of God is it then?’ said Big Harry.

‘It’s a jaynius,’ said my father, launching into a ballad about the birth of some genius or other called Daniel O’Nayle and a wet-nurse called Judy Callaghan. It was a song that gave itself liberally to numerous asides, shaking of hands and humorous toasts and could last anything up to an hour in the hands of Mick Sands.

My father’s family, 1924, musicians all (back) James, John, Kath, Patrick (senior), Pat, Hugh and Mick (my father) (front) Peter, Mary Alice, Vera, Mary Ann, Benny, Annie and Clare

Next he took out the fiddle. ‘On your feet,’ he shouted. Tunes learned from his father’s four brothers, who were fiddlers, and his father’s four sisters, who were diddlers, danced around the rafters. He was the carrier of a clan tradition and later would become known to all and sundry as the ‘Chief’. He could handle any gathering with ease and there were few entertainers in the whole of Ireland like him whenever he got into his stride. By the end of the week, however, there would be little left of the pit of blue spuds.

When my mother came home, she and my father seemed to recuperate at a more or less equal pace and things slowly returned to normal.

The events of that day I can only assume to be true. It’s what I was told. I wasn’t exactly there myself – I was too busy being born in Rathfriland Hill Hospital – but it is certainly in keeping with a family ritual, with which I would later become familiar.

All seven of us were Caesarean born. Mary Philomena came first, called after our two grandmothers, Mary Ann and Mary, and a saint called Philomena. Hugh James was next, called after Uncle Hugh, who was in prison in China, and our two Uncle Jameses. I came after Hugh and Patrick Benedict came after me. He was named after our two Uncle Patricks and Uncle Benny, who was soon to die in Africa. Then it was Peter Colum, so named because we had two Uncle Peters and an Aunt Columbanus, who was a nun in Dublin. After that, John Eugene came along and although he was named after the only Uncle John we had, as well as the bishop of the time, Eugene, the Pope of the time and our maternal grandfather, Eoghain Connolly, he ended up just being called Dino. Last came Brigid Anne. She was called after our mother, our great Aunt Brigid, St Brigid, and three Irish goddesses, all called Brigid. Later she was simply called Anne. According to my mother, Anne was the name of God’s granny, the mother of Mary, the mother of God. A child’s name, the old people would say, is more than a word to call it by. It’s a history of its own past and an assurance that the souls of the ancestors and the sacred spirit of creation will continue into another generation.

Without doubt, both sides of my family had a strong sense of belonging and felt a close link to the distant past. The Sands side had a Norman connection, but according to my Uncle Hugh, we were here long before the Norman Conquest, being descendants of Seanán, who founded a monastery in the sixth century on Inis Cathaigh (Scattery Island) at the mouth of the river Shannon. Uncle Hugh always signed his name Aodh Ó Seanán. The Connollys were descendants of the local chieftain, Mac Chineallaí, who is buried with earlier chieftains under the ancient cromlech in Burren.

My grandparents were dead and gone before I arrived in Rathfriland Hill, all, that is, except my father’s mother, Mary Ann. She wore a long black shawl and came from the Cooley Mountains, where songs were sung in Irish (Gaelic). Looking back, I see her faintly, like the Old Woman of Beara, bearing the joys and the pains, the questions and the answers of a thousand lifetimes. She was going and I was coming when we met, and I sometimes feel that in that short time she had an effect on me I can’t explain. When a person is too old to talk and another too young to understand, it is time to go beyond all that and sing:

I remember

When I was two,

At least,

I think I do.

Or maybe, then again

It was because

What happened then

Has been so often spoken of

Again

And now again.

It was the day that we rushed

To the banks of the Rushy Bottom,

Mary and Hugh and I.

The moily cow

Had fallen into the flax dam,

She had no horns that you could catch her by.

‘Catch a hoult of her there,’

Said neighbouring men

On the brink of the bog.

‘Has nobody a rope?’

The dog barked out the clear confusing

Darkening hope …

My granny wept at the haw-lit hedge

With blackened shawl and whitened head.

‘If I was at myself,’ she said,

‘I wouldn’t let that happen.’

She sang a song of Ireland’s tears,

Her present, past and future fears

In lyrics of her younger years

And music without ending.

A dhruimfhionn donn dílis

Is fhíor-sgoth na mbó

Cá ngabhann tú san oíche

‘S cá mbíonn tú sa ló?

Ó! bím-se ar na coilltibh

‘S mo bhuachaill im chomhair

Agus d’fhág sé siúd mise

A sile na ndeor.

Oh beloved little cow

Oh silk of the kine

Where do you sleep at night

What pastures are thine?

In the woods with my herdsman

I always must keep

And it’s that now that leaves me

Forsaken to weep.

‘Please wee God, bring Mammy home’ was the first song I ever sang and the first prayer I ever said. We were kneeling on the windowsill, facing nightwards, Mary, Hugh and I, and I was four years of age. Later we changed it to, ‘Please wee God, send Mammy home,’ for, as Mary pointed out, you would hardly expect God to bring her home on his back, and him so small.

The wee God in question, the Infant of Prague, sat vague and motionless on the mantelpiece between two sad dogs. There was another picture of God hanging in the bedroom with the blood coming out of his heart, who had enough troubles of his own without taking on heavy lifts over hedges and ditches. We knew, though, that the power was there if only we got the singing right. Ben, the new baby, cried in the cot without care.

The only one who seemed to be taking notice of our prayers was a cautious spider parked in a cobweb at the top corner of the small eight-paned window. He reversed a few legs backwards and listened. A cobweb or two wasn’t out of place in those days, for as the old people used to say, ‘Why would you get that oul’ dirty fly paper when there’s a good clean spider about?’ Our good clean spider still waited and watched, and so did we, and somehow his witness helped to relieve the strain of it all.

We were used to waiting, of course. My mother was often out working in the fields, tying summer sheaves behind my father’s scythe, stooking sheaves and shigging stooks. Then it was butting stacks with bushes and thatching them with rushes to keep them dry till McConville’s threshing mill would come around. It was only when wee God sent a sudden spit on the windowpane that we knew she’d be home soon with corn for the hens and chaff for the tick. Or maybe she’d be gathering autumn spuds behind our father’s spade, hopping at a pit or skipping at a skip. Then wee God would send the hat of darkness and that would bring them both home, trudging with a half-hundred of spuds for the dinner. But tonight it was different.

There had been no work done today. The darkness already had settled over the small empty fields. A bodiless coffin lay in my granny’s house. Her youngest son and my father’s favourite brother, Father Ben, lay dead in Jos, Nigeria. Forty years later his ant-eaten diaries would be found, telling the story of his life and death, but for now there was nothing, save an empty wooden box in the corner of the parlour to remember his once full-of-life presence, and to have something for people to gather round. My mother had been at the wake making sandwiches and meeting mourners but she should be home by now. There was something wrong. It was only three or four fields of a journey she had to make and she had crossed that path a thousand times.

There were things out there in the dark that we didn’t understand, especially at times when souls were making their way between worlds. There was hardly a field or loanin in the townland where someone hadn’t seen or heard something strange or unearthly. There were stories of ghosts galore and even occasional sightings of the boyo with the horns and the tail. And then of course there were the fairies. I was already vaguely aware of their powers and inclinations. According to my father there were many tribes of fairies, all with their own sense of place and space and each expecting the respect of humankind. Our Uncle Hugh had once heard their music in those fields and we knew they had their way of enchanting the most sensitive souls into their world.

During that night I must have fallen asleep in my sister’s arms, for the clacking of the latch startled me awake. It was almost day. My mother stood there strange and frightened. My father’s arm was around her.

‘Kneel down,’ he said quietly. ‘We’re going to say the rosary. Your mother stepped on a stray sod tonight.’

He had found her on his way home from the wake, wandering around lost in the Field above the Dams, close to the Rushy Bottom, searching in vain for the stile she had crossed a thousand times. The fairies had planted the stray sod there and the only way to escape their spell was to take off your coat, turn it inside out and then put it back on again.

Mother, 1939

She smiled as she bent over and gently kissed me. ‘Everything will be all right,’ she whispered.

The Infant of Prague still sat on the mantelpiece, looking vague and mysterious, but we knew our song had done its job. My mother sang another now and soon we were asleep.

I remember her as she was that night, young, strong and beautiful. A lifetime later as she slipped into another world, unable to walk or talk with the plague of Alzheimer’s disease, she still had that same gentle smile. When people would say, ‘Look at her soft skin; she must have been very beautiful!’ I would nod my head and think of those times. That same smile brought us through many a troubled hour.

The lilt of my father’s fiddle leaking under the bedroom door, accompanied by the faithful flicker of the kitchen’s double-burner oil lamp, was my first sense of awakening in the world of music. I should have been asleep, of course, but when the neighbours came, with black bottles squeaking in their inside pockets and magic stories swilling from wicks of well-oiled lips, it seemed, even for an innocent child, more sinful to sleep than to wake. Besides, there was still some blue left in the late summer evening, taking one last look, through the small sashed bedroom window, at my half-opened eyes.

They had been gently closed earlier on by the soft sound of my mother’s singing. ‘Daily daily sing to Mary’, she sang. At first the words puzzled me. ‘Why do you always sing to Mary instead of me?’ I asked, and now that I had raised the subject, ‘Why does everyone thank Hugh all the time and never thank me?’

My sister and brother shook hilariously at my sincerity but my mother smiled seriously.

The Mary in the song is God’s mother, not your sister,’ she explained quietly. ‘And it’s “thank you”, not “thank Hugh”,’ she added with a chuckle.

That song would often fill me with both relief and frustration. It would ease me into a heavenly sleep, but I didn’t always want a heavenly sleep, especially so early on an earthly summer’s evening with the house filling with voices and fiddles.

It was almost dreamlike; I was somewhere between waking and sleeping. The four small panes in the top half of the sash window vibrated slightly. Perhaps it was their shivering dance that prompted a new awakening in me. Its tune was being called by a more distant voice, effortlessly now, searching for a listener. It was louder, thundering, and it came tumbling over the hedges and ditches of Ryan from Desert Orange Hall, one full mile away. It was the sound of the Slashers. Sometimes my father’s bow arm would slacken or speed up, willingly or unwittingly, to the pace of the rumbling drum and, in time, the hum of the Lambeg seemed to drone in perfect beat with the fiddle. The sounds were coming from different places, a mile apart, into the same room, my room, under the door and through the window.

When I was older, I would be told how these sounds represented cultures that were light years apart, but then, innocent and unladen by such learning, I knew no better and sailed deeper into a sleep-filled, peaceful ocean, with a Fenian fiddle in one ear and an Orange drum in the other. The tunes being served in my mother’s Irish Catholic kitchen were to be played by us the world over and had as much of a Scottish snap as an Irish lilt, and no wonder. Among the fiddlers who played were Glennys, O’Haras, Reids and Cowans, neighbours good and Protestants all. Tunes drawn from the same well cemented our friendships and strengthened the traditions of both. The Slashers’ loud drumming, like shots over the head of such quiet alliances, beat out an unease my innocence could not hear.

Later I would learn that the Lambeg drum had come on horseback with King Billy and boomed out the triumphs and failures of his battles. Was its sound, which owed half to the way it was played and half to the way it was made, playing out the fear of a planter culture being integrated into and disappearing within a strong native tradition? In coming years, as many Protestants would retreat into their own communities and militant loyalists would threaten to bomb pubs and clubs where traditional music was played, I would wonder and ponder upon these sad, strange ironies. You can be sure, however, that such complexities were far from my consciousness that night, or I would not have slept at all.

Outside, the moon peeped over the hedge that shielded our small rented farmhouse from the canaptious moods of the north wind. It was made of boxwood, trained especially to keep Wee Willy Wilson’s three cows from eating my mother’s primroses and daffodils, and to keep his sow from eating our rooster and four hens. The hens were useful, for they laid eggs, some of which would be eaten by Wee Willy’s half brother, Big Davy, who was our landlord and who came faithfully each week on Flo, his mare, to collect the rent of sixpence.

I would always know when Davy Wilson was in the house, for my mother would change her pronunciation slightly when he came. She would try to sound the g at the end of words like sowing and mowing. Some Protestants tried to talk ‘proper’ English, like the royal family, and my mother would lapse into that language out of respect for them. She wouldn’t go so far as pronouncing the letter h (haich) as aich, or lough as lock or call Derry Londonderry, but that was because her tongue had no experience of shaping itself that way. My father would speak the way he always spoke no matter who was about, for he didn’t give a ‘dang’ about the Queen, and besides, ‘Protestants would respect you all the more for being yourself,’ he maintained. ‘When I’m sowin’, I’m sowin’,’ he would say, ‘and when I’m mowin’, I’m mowin’.’

I stood as a marker for the ‘corn fiddler’

From the minute I was on my feet, I’d stand as a marker in the field when he sowed grass seed or corn out of a brown bag apron or a red box fiddle, and he’d walk straight towards me, taking in one breadth at a time. And when he mowed with the scythe, I would hold back the heavy corn with a long stick to make the cutting easier, reversing down the field in front of him, keeping bare legs well away from the swishing blade. I also held back for Wee Willy, who, for his size, took a very wide span with the scythe and called it a ‘swathe’ rather than a ‘sward’.

Wee Willy and my father owned a billhook between them and anyone who wanted to borrow it needed permission from them both. The shaft and blade had been replaced several times over, but it was still the same billhook nevertheless.

In many ways my father was as Catholic as Willy was Protestant, as Irish as Willy was British, as green as Willy was Orange, as republican as Willy was loyalist. They had their differences but making war was not for them, they made hay instead. In later years their relationship inspired a poem.

I see him now half hidden by the hedge,

Briarding.

Hacking away with the billhook, that

He had joined in

With Wee Willy Wilson. Half

Cutting them through, then

Bending them over.

Crossing the march with thorns

To make good the divide,

And keep the peace,

To save bother.

Fresh new blood drops

Fell from his fingers

Like ripe cherries.

‘This work has me crucified,’

He said.

As a young child growing into a troubled Northern Ireland, those first five years were formative and unforgettable. We were soon to move just a few fields away to Elm Grove, the home house willed to my father, an inheritance he found more often a burden than a bonus. His visions and ambitions lay far beyond the Ryan Road, but he was tied to the small farm and it would have been nothing short of treachery to have forsaken it. Besides, there was little else to make ends meet.

We lived there happily beside the Protestant neighbours, but during the ‘Davy days’ it was something special, like one big family. We were in their houses, drinking their tea, pooching for goodies in their drawers, eating their buns before they were baked, following kittens under their beds and singing their songs. The kindness and friendship of the Wilsons, Davy and Margaret, Wee Willy and Martha, Tom and Nora, and Iris and Willie McMullan, would be forever reassuring and would endure deep into the tense years that lay ahead. It wouldn’t mean that convictions would change or differences would be denied but it would ensure that we would begin the long journey not as enemies in search of a conflict but as friends in search of a solution.

‘Martha’s going to heaven, Protestant or no Protestant,’ said my mother. It was the first time I heard that a Protestant might have a problem getting into heaven.

Many years later, on some far-off Good Friday, the Lambeg and reel would be heard once more, as weary politicians agonized over new answers to old questions. Their music would represent different sides of the same coin, the only currency available. They would somehow sound strangely harmonious, like a cushioning twilight, between waking and sleeping, between sleeping and waking.

3

Before Books

Summers were hot then, with colour-coated butterflies floating above the primroses and cowslips of the front garden, which was really a field like the others except it was smaller. In the centre stood a long lone stone like a last stump of a tooth in the gums of history. It had been there nibbling at, and being nibbled at, by time, according to my father, for maybe 4000 years. It stood at ease now without the need to do much. We chased around it trying to catch butterflies with cages made from rushes and if we managed to catch one, we would bring it into the house and keep it as a pet on the windowsill, in the hope it might live longer when the cold weather came. Sometimes we would make a train out of a plank of wood placed on top of empty treacle and syrup tins and roll down the mossy hill for hours and hours until the stone cast a long shadow and our mother would shout, ‘Childer, childer, are you not going to come in the night at all at all?’

When the dark nights came, we would take turns at the bellows wheel, and the blue flame from the slack would lick the bottom of the big three-legged pot that hung from the crook that hung from the crane that reached across the hearth from hob to hob. The seasons went round too, wheeled by another hand, each with a special sign to tell the tale of its turning.

Above the fireplace hung the Cailleach, the old woman who hid in the cornfield like the spirit of the harvest. She would stay there during the winter for good luck. All that was left of her were the neatly plaited corn stalks of hair. She had arrived on the back of the north wind, with a besom in her hand to sweep away the old year in preparation for the new. I couldn’t wait for a new harvest to come when I might catch a glimpse of this mysterious Cailleach in her prime, all of her. The old people said that at present the rest of her was in the earth for it was in darkness that the story of life was born.

‘Whenever you go to school,’ my father said, ‘you’ll learn about things written in books, but first of all you’ll have to learn about things that happened before books were written. Did you know that there were no books in Ireland before St Patrick came with his monks and their goose-feather pens? History was memorized and handed down in song and story by the poets and the bards from generation to generation, from when Adam was a child until the present time. It was a holy thing to recite the paths of the past, because it led back to heaven and will lead there again, if you’re all good childer,’ he went on, warming to his task and poking the slack with a stick that he used for coaxing cattle. The bellows wheel would have stopped when the story started.

Father and Mother, 1959

‘How could they remember everything?’ asked Mary, who had already started school and was trying to learn her catechism for First Communion.

‘Well, right enough,’ says my father, ‘there were a couple of Ice Ages and a flood or two, so they might have lost concentration now and then, but the gist of what the old people told the monks and what the monks wrote down in the seventh and eighth centuries would be as true as any ancient history. Although,’ he continued with a wink of an eye that wrinkled his nose and a half of his mouth, ‘you can be sure that the monks gave it a twist to suit themselves and fit it into the new religion they had brought with them. Just like the Sumerians or the Hebrews, though, stories were told and pictures were painted to explain mysterious happenings, because our wee brains can’t grasp it any other way.’

My father had little formal schooling but, as he said, he met the scholars coming home and listened to old people who had learned to school themselves.

The stories lasted for weeks on end and would be continued the next night or the next day as we followed behind his spade, gathering spuds into a bucket. ‘Gather up now, yiz boys yiz,’ he’d said. ‘The rain’s coming on.’

‘If we do then,’ bargained Hugh, ‘will you tell us the one about the first people that came to Ireland? Not the one about Noah’s granddaughter who was thrown out of the ark and arrived on a raft, for that’s too sad. The other one about the fairy people.’

‘At the head-rig maybe,’ he’d answer, and with a contented grunt, his left knee would prise out a spadeful of heavy dark brown clay, laced with dead stalks, redshanks and gil-gowans. From somewhere within, there’d suddenly float a flood of bouncing, bright, newly born spuds. Another flick from the spade’s shiny point, like that of a master hurler, would fire them individually into our field of play.

Under the hedge in the Low Field, with the silver drops of rain tapping on the hessian sacks about our shoulders, we’d learn how Michael the archangel, with his gang of good angels, lined up in heaven against Lucifer and his gang of bad ones, and how that affected Ireland to this very day.

‘When the word got out that the battle was going to take place, there was a lot of recruiting, as you can imagine,’ said my father. ‘“All good angels this way,” shouted Michael, “and we’ll soon drive these bad angels out to hell.”

‘“All bad angels line up behind me,” said Lucifer, wagging his tail in all directions. “Come to my side of the fence and you won’t be far wrong. We’ll teach these good angels a lesson or two.”

‘There was one group of angels, though, who didn’t want to go to either side of the fence. “We’ll sit where we are,” they said. They didn’t want any fighting and they even went as far as to suggest that God and the Devil should shake hands, if you don’t mind.

‘“I’ll remember you crowd,” said Michael under his breath.

‘“I won’t forget you either,” hissed Lucifer.

‘Well as you know, the fighting started and the Bible can tell that part far better than me, but at the heels of the hunt Michael won the battle and proceeded to throw Lucifer and the bad angels out of heaven. As he was heaving out the last of them, though, he saw out of the corner of his eye the ones who had not taken part, all trying to look very small and giving wee innocent smiles as if to say, Did you hear us cheering for you?

‘“Out you go as well,” roared Michael, for the vengeance of war was still inside him and out he pushed them, twisting and turning, begging and pleading over the hedges of heaven and into the general direction of hell.

‘Well as it happened, God, whom they say is very merciful, was walking past at that very moment and he saw what Michael was doing.

‘“Are you not a bit hard on those wee angels?” he asked. “They might not be good enough for heaven but they’re hardly bad enough for hell.” And he pulled an almighty lever, which put a brake to their fall, and they landed exactly halfway in-between, which was, of course, the earth. Now, whatever way the earth was turning at the time, Ireland was pointing upwards and that’s where they landed and here they remain to this very day. And that’s how the fairies, or the sí, as they’re called, arrived in Ireland. They must be respected,’ said my father finally. ‘They have a lot of power and they’re full of tricks.’

I thought about the stray sod. It seemed believable enough. I looked up to the top of our lane and saw the fairy thorn bush that no one would ever cut a twig from. I had watched our cousin Johnny Brennan give his fairy thorn a wide berth as he awkwardly arched his ploughing horses well clear of its whitethorn fingers. Another cousin, less wise, had cut down a fairy bush and was well rewarded with a slobber and a stammer which he would carry to his grave.

‘Have they white blood?’ I asked, knowing that they had, but trying to prolong the story, for the rain was beginning to ease.

‘But it wasn’t the fall from heaven that crashed them under the ground. Isn’t that so?’ said Mary, who was the eldest and knew more.

‘How they got under the ground is another story altogether,’ said my father, rising. The rain had stopped.

‘But that’s the story I wanted to hear,’ Hugh complained.

‘Bobby Graham, the potato man, will be wanting to hear another story,’ said my father. ‘We have to have a ton dug, gathered, skipped, bagged, weighed and sown with a packin’ needle before this day week. There’s a lot of bills to be paid, you know. Gorman’s grocery shop at the Bridge can’t wait forever and there’s new brogues to be bought.’

I looked down at my boots. They had been handed down from Mary to Hugh to me. Ben would be next in line but my toes were already looking out and the boots were letting in. I slowly followed the others back to the digging.

It would be a long time before we would hear the end of that story. We had hoped to get Geordie O’Hara or Pat Brennan to come with the wee Ferguson tractor and drag digger to finish the digging but the weather turned for the worse and it rained for weeks. My father dug on with the spade, his back ‘broke’, and we gathered around him until it was well into frosty December. Our fingers were bitter with the cold but wearing gloves would have been out of the question. ‘What sort of an oul’ woman are you?’ he’d say, if you even mentioned the word.

When the job was done and the sacks of potatoes sat in the shed, we prayed we had not put any bad ones in, for we had heard that Mr Guy, the inspector with the moustache, was very particular. Buster Lennon came for the spuds and we hoisted them up on Graham’s lorry. Soon they would go to Newry and the cheque would arrive. Gorman would be paid. We would get new boots and proudly head off to the pictures in the town and get chips afterwards in Pegni’s, for that was the treat when the spuds were sold. We watched the lorry slowly drive away up the loanin, tired out but with a great hope inside us.

It was not to be. Mr Guy had found rust on the spuds because of the wet season and had turned them down. It would mean we would have to pick and sort them all again. We didn’t have much time for men with moustaches for a long time after that.

My poor father took to the drink for a week with Big Harry and Wee Harry, while the condemned spuds remained in custody in a corner of Bobby Graham’s yard in Newry.

It would be many weeks before those spuds were sold and many more again before the story of how fairies got under the ground would be told. In the meantime, we would have heard of other wondrous happenings and learned how to cut new seed spuds through the eye for dropping in drills and to prepare lea ground for the fiddling of corn and grass seed.

The first flower I remember seeing was a snowdrop. It appeared on the ground as silently as a snowflake. There were as many secrets in the earth as there were in the sky. No one remembered planting it. Perhaps it always was there, just awaiting a wink from the eye of heaven. Slowly the days were becoming brighter and birds were singing. The first bird I remember was the lisinaree. Its real name was ‘finch’ but at the end of every verse it sang lisinaree!

When the first of February came, the Cailleach was replaced with a brand new St Brigid’s cross that Mary had made from rushes in the Rushy Bottom. That was St Brigid’s feast day and Auntie Maggie would arrive on foot to take us to St Brigid’s Well in Faughart. We walked the two miles up the Ryan Road and got a bus to Newry, took another bus across the border, and then walked the last three miles to Faughart.

Auntie Maggie had great faith in the water from that well and she always took children with her. My father used to say that all Burren children had one arm longer than the other from being dragged all over the country by our well-loved Auntie Maggie. She sprinkled the holy water on us, on the animals and on the ground too, for the earth was full of growing and needed to be looked after. She whispered to us that Brigid was a saint even before Jesus was born. We peered down the well, hoping to catch a glimpse of her, but Auntie Maggie warned about the wee girl who wanted to know too much and the well swallowed her. Her name was Shannon and that’s how the river Shannon began, and it was a very knowledgeable river.