Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

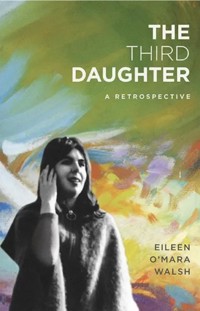

The Third Daughter begins in 1940s Limerick, where the O'Mara family were merchant princes of the city. The story follows the family fortunes from middle-class comfort to genteel poverty as they moved to Dublin and became part of its literary and theatrical circles in the 1950s and 60s when her father Power O'Mara managed the avant-garde Globe Theatre Company. Eileen's mother, Joan Follwell, was a glamorous English socialist, becoming a lover of philosopher Bertrand Russell in the 1920s (twenty of his letters are in the Appendix), and leaving London with her Irish husband during the Blitz in 1940. Eileen recalls influences and people of her youth, from Patrick Kavanagh to Michael Mac Liammoir, Noel Browne to Conor Cruise O'Brien. Eileen migrated to London in 1959 and in 1960 moved to Paris, working for an international Catholic women's organisation. This brought her to Rome and to an audience with Pope John XXIII. Back in Dublin in 1962, in a bohemian milieu of painters and writers such as Sean O'Sullivan, Camille Souter, Louis Marcus, Aidan Higgins, John Jordan and others, Eileen met Mayo artist Owen Walsh and returned to Paris with him in 1967 to work for the newly established Irish Tourist Board, going on to win the Club Med franchise for a burgeoning Irish market. In 1975 Eileen and Owen's son Eoghan was born. Eileen separated from Owen two years later and in 1978 began the O'Mara Travel Company, becoming one of Dublin's most accomplished businesswomen of the 80s and early 90s. She was the founding President of the Irish Tourist Industry Confederation, a director of Aer Lingus, and was the first woman in Ireland to be appointed Chair of an Irish commercial semi-state company in Great Southern Hotels. Later she became Chair of Enterprise Ireland precursor Forbairt and Opera Ireland, was a founding member of Dublinia, and through her business career encountered figures like Desmond O'Malley, Charles Haughey, and Bertie Ahern. The memoir concludes in 1996 with the 21st birthday of her son, Eoghan. An Epilogue in 2002 gives a moving account of Owen Walsh's illness and death from cancer in Mayo, where the couple find time together again. This is a remarkable memoir by a woman who helped give shape to contemporary Ireland, formulate tourism policy, and who bore significant witness to the artistic Baggotonian Dublin of the 1960s and beyond.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 580

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

1. Listen with Mother

2. Searchingfor my Father

3. At Home

4. The Outside World

5. The Fall

6. Dublin and Adolescence

7. Pubs, Ploughs and Players

8. Ruth

9. Skiving and Jiving

10. Floundering in Flanders

11. London Calling

12. Paris, L’Education Sentimentale

13. Paris: Rue de Vaugirard, 1961

14. Baggot Street, 1962

15. ‘So True a Fool is Love’

16. The Plateau

17. La Maison d’Irlande 1967

18. ‘Since There’s No Help …’

19. The Web – and the Webbing

20. Mourning My Mother

21. Troughs and Travels

22. Babies and Bathwater

23. Beginnings and Endings

24. Other People’s Business

25. Parallel Lines

26. Still Waving

Epilogue

Appendix: The Russell–Follwell Letters

Illustrations

For my son Eoghan

Preface and Acknowledgments

Dublin January 2011: Three score and ten, I had reached my biblical allotment of years. I was already five years older than either of my parents at the time of their death. My business life behind me, I was now embarked on an MA degree in modern English and was facing the task of writing a 20,000 word thesis with less than enthusiasm.

At about this time I encountered a couple now in their eighties who, as young people, had known my family in the 1950s. Entranced, I listened to their anecdotes, still fresh and warmly affectionate about both my parents; but their recollections of my father as a charmer, full of bonhomie, a joker and raconteur, intrigued and saddened me. It was not the father I remembered. An idea dawned gradually that once planted kept nagging until I realized that I was going to abandon the thesis and instead write my parents’ story.

I would try to solve the mysteries and silences that had shadowed my childhood and trace the route that took a War of Independence exile and son of an opera singer to meet and marry an English socialist, erstwhile lover of Bertrand Russell. I would delve into my own memories of childhood in Limerick and adolescence in Dublin when Patrick Kavanagh paid my busfare home and my mother scolded Brendan Behan for putting his boots up on the kitchen table.

This is why TheThird Daughter was begun. A coda worthy of Dickens coincided with its ending. In October 2014, as I walked through the restored Victorian buildings of the new DIT Campus in Grangegorman, a ghostly finger touched my cheek in valediction or remembrance of their previous incarnation: the desolate wards of St Brendan’s Hospital, where my mother spent the last weeks of her life.

That this search for my parents has run away from its best intentions and become a chronicle of my own life as much as theirs is in no small part due to Paul Durcan, whose gentle but unrelenting persuasion drove the story ever onwards.

Eileen O’Mara Walsh

March 2015

*

The poem ‘Portrait of the Artist’ from Cries of an Irish Caveman by Paul Durcan is by kind permission of the author. The correspondence between Bertrand Russell and Joan Follwell is by kind permission of The Bertrand Russell Archives, McMaster University Library, Ontario, Canada.

Thanks are due to Dr Kenneth Blackwell, former archivist of the Russell Collection, for his courtesy to my mother in 1971 and to myself in 2014; to Eoin Purcell and Sine Quinn for their professional advice and encouragement; to Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press for his faith in The Third Daughter, and to the unerring eye of his own daughter, Bridget; to Djinn von Noorden, for her editing skills and shrewd comments; to Mairead Breslin Kelly and Stephanie Byrne, friends and early critics; finally to my son Eoghan, to his wife Yvonne, to my sister Mary and to my extended O’Mara and Walsh families for their love and friendship.

1. Listen with Mother

LIMERICK1941

The O’Mara family was typical of the wealthy Catholic merchant class that had emerged in Ireland from the middle of the nineteenth century. Thus it was Kate O’ Brien’s Limerick rather than the city of Frank McCourt where I was born in 1941, third daughter of the IRA son of an operatic tenor and Freeman of Limerick, and the Fabian daughter of a Salisbury socialist. In fact we had a close connection with Kate O’Brien, insofar as her sister Nancy was married to my father’s first cousin, Stephen O’Mara, and lived in some grandeur at Strand House, only a short walk from the more middle-class redbrick of no. 4 Moyola Terrace on the Ennis Road where I spent most of my first ten years.

When I think of my parents, my mother always comes first to mind and is still a constant commentator, mentor and arbiter against whose taste, judgment, beliefs and prejudices I measure both myself and the world around me. Those early years in Limerick must have been golden ones for Joan Follwell, despite her difficulties as a foreigner, and an English convert at that, in the tight class structure and religious bigotry that characterized the Limerick of the 1940s and 50s. She was, according to all who knew her then, a beauty of the elegant, bony type epitomized by Hollywood legends such as Joan Crawford or Barbara Stanwyck, upon whom she quite likely modelled herself. She was the first woman to wear slacks in Limerick, her clothes square-shouldered and mannish except for the long housecoats, buttoned all the way down to the floor, which she wore in the evenings. She professed to despise jewellery and I never remember her wearing any except a string of pearls and an ornate signet ring of my father’s. She was famous for her hats – or rather hat – as she always wore a variation of the same one, a turban, fashioned to her design by the modest local milliner-cum-dressmaker who made all our clothes. Indeed when we moved from the salubrious area of Moyola Terrace to the more working-class precincts of Crescent Estate, she was known, among the more daring of the local lads, as ‘the Egyptian prime minister’.

In retrospect when trying to write about my parents, Power and Joan O’Mara, in their own context rather than simply as the progenitors of my important self, I find, whereas my father’s story is vague and difficult to recreate, that my mother’s early life comes effortlessly to the page. She had imprinted the images of her girlhood and youth so vividly on my memory I almost felt it had all happened to me, so if his voice is faint, hers is not. As Bertrand Russell suggested in one of the twenty-odd letters he wrote to Joan, she may well have had an undeveloped literary talent that expressed itself largely through her letters and through sporadic attempts at composition, both of prose and poetry.

Joan’s father Edward Follwell was born of middle-class parents but his mother was widowed early and he went to work as an office boy at twelve years of age. This experience turned him into an early activist in the young British Labour Party and led him to identify all his life with Charles Dickens; so much so that he used to tour local halls and meeting houses and give readings of Dickens to earnest working men’s groups. Joan’s mother Maude’s maiden name was Davis and she came from Bristol. She too died young and would have completely disappeared from family history but for her two sisters whose Christmas and birthday cards were awaited so eagerly in Limerick half a century later. Those red ten-shilling sterling notes represented untold treasure to their recipients, who dutifully wrote their thank-you notes to those unknown foreign species, ‘Dear Aunt Mabs’ and ‘Dear Aunt Nell’. Edward Follwell married again, not to a cruel stepmother, but to a gentle lady known as ‘Mater’ by Joan and ‘Grandma’ by her Irish step-granddaughters. He married yet a third time, much to Joan’s mortification, after Mater’s death in the 1950s, to Phyllis who was half a dozen years younger than herself. The fact that Phyllis had a club foot slightly mollified her, together with the realization that her father, self-centred to the last, had ensured he would be looked after in his Salisbury home for the rest of his life.’

Joan’s own words brings the child and later schoolgirl vibrantly to life:

In those days we all wore sailor suits, boys and girls alike. Naturally the girls wore skirts and the boys were differentiated by sometimes having attached to their collars a silver whistle, held by a white cord. It was in such suits that we (my brother and I) were dressed by a kind friend of the family after our mother had been removed to the hospital where she afterwards died. The fact that we had to be so completely fitted out brings home to me the poverty of our parents. We lived in Wood Green [London] in a dark flat of which I remember chiefly the texts on the walls, ‘In all thy ways acknowledge Him and He will direct thy path.’

The first time I entered a Catholic church I was nine years old. It was somewhere in North London, a wild and stormy night. I was walking with my father and ahead of us were my mother and my little brother, he hanging on her arm and she wiping her nose through her veil. She was beginning to cry already and I knew what it would be like when we got home so I was glad when my father stopped before a building from whose half-open door light shone out. Inside it was brighter than anything I had ever imagined, people were standing and singing and we stood too, not singing but staring about us at the lights and the sweet-smelling incense that rose from the altar. When everyone sat down we sat too but when a bell rang and everyone knelt we continued to sit, my father disregarding with a smile the gestures that beckoned us to follow suit. I would gladly have knelt, felt painfully our conspicuousness as the bell rang again and all heads were bowed but ours. We came out again into the starry night while my father talked of Joseph McCabe, Boyd Barrett and the beauties of rationalism (so unlike Little Therese). When we reached home, my brother was in bed and my mother’s lamentations were louder than ever before. ‘When I am dead, you will be sorry.’ My heart had broken already earlier in the evening when I had watched without seeing the comic film my father thought would cure my mother’s grief – I knew then, sitting in the plush seat feeling in the darkness her agony, that we were doomed. In the morning she was gone. I never saw her again. After my mother’s death my brother and I never spoke her name.

I was sent to St Gilda’s Convent School in Yeovil, Somerset in 1916 when my mother became incurably ill and died soon after. I remember that my father deputed someone else to break this news to me and that all day I avoided by a show of high spirits being told what I already knew in my heart. Sister Superior I have described elsewhere but all my writings, my diaries, my letters were lost in the ‘Blitz’. Her name in religion was Sister Ste Hermiland. She was very small, very dark; her skin was pock-marked and her lips the deepest most velvety red. At ‘recreation’ she would stand with her arm around me. This, I see now, accounted for the lack of popularity I so longed for and why school was not the least like those I had read about in the books of Angela Brazil.

We all wore black pinafores in the French fashion and for lack of looking-glasses we preened ourselves before the glass of the cloakroom door. We went for long walks in ‘crocodiles’ and were so hungry that we ate everything we could find. The taste of beech nuts and their shape remains with me still. Also sloes, which did things to one’s mouth and of course, blackberries and even hips and haws.

The waking bell. Daily Mass was not compulsory, especially for non-Catholics, but I knew her eyes were fixed on me and even though the sweat came out on my forehead and strange bells rang in my ears I continued to kneel. To faint and die and receive Sr Hermiland’s smile as I was carried out to recover on a cold tombstone was victory indeed. She was sad to see me go. She summoned me to her room and standing breast to breast (she was exactly my height) she pressed her velvety lips on mine while the wings of her coif enfolded both our faces.

Why Joan’s father, a principled atheist, ever sent her there is obscure. Her resulting conversion to Catholicism was at first passionate, then lapsed into agnosticism, reviving again on her marriage but remaining idiosyncratic with leanings towards mysticism and ritual and a hatred for the dogmatism and prejudices of the Irish Catholic Church. Her account of boarding-school life holds huge resonances in our family history. Her husband, my father Power O’Mara and his younger brother Joe, who became a Jesuit priest, were both products of the Jesuit boarding-school system; both gentlemen and gentle men, but it may have sucked some essence, some vital spark from their personalities: ‘Give me a child before he is seven and I will give you the man.’ For Joan, the cloistered life seemed always to hold a romantic attachment. In her old age she wistfully spoke of ending her days living in a convent cell, with recourse to books, a plentiful supply of Sweet Afton and the occasional Baby Power.

Part of the ineradicable literary legacy she imprinted on the hearts and minds of her daughters Mary, Ruth and Eileen was her reading aloud; for instance, Antonia White’s Frost in May was narrated with great relish to me, her youngest daughter, whilst her eldest, Mary, ironically raged and fulminated against her eight-year incarceration as a boarder in the Sacred Heart Convent, Roscrea. This life sentence had a deeply damaging, lifelong effect on that mother-daughter relationship. Yet Joan did not see, or perhaps refused to see, that her own version of sentimentalized convent life in First World War England brutally differed from the reality experienced by Mary in the Ireland of the Emergency and the implacable jansenistic sect that was Irish Catholicism. Her two younger daughters, Ruth and later myself, happily attended the Faithful Companions of Jesus Convent, Limerick, as day pupils.

The pains and perils of Limerick and Roscrea were far from the life twenty-one-year-old Joan Follwell was enjoying when she first encountered Bertrand Russell. She describes their first meeting in April 1927:

When I was a young girl, living in Salisbury in the nineteen-twenties, my family were pioneers in the Socialist movement. We were all members of the I.L.P. [International Labour Party] and we played our part by giving hospitality to visiting speakers for the Cause. It was in this way that I met Bertrand Russell, or rather, that he met me, for me he was just another political guest (we had had Emmanuel Shinwell the previous week-end). As I waited for the bus at Harnham Bridge I felt a little more than the usual excitement and anticipation that an important speaker normally aroused. I am sure this was not because he was ‘Lord’ Russell, it was because he was a writer and I had secret ambitions of my own. These I confided to him as we walked home. But I was dismayed and my parents were quite nonplussed when he asked after supper if we might be left alone together so that I could show him some of my ‘work’! This work was practically non-existent – two chapters of an autobiographical novel, but he asked me to read it aloud to him. I had not proceeded very far when it became clear to me that he was far more interested in my mouth than in the words I was reading. So I said, with genuine feeling but with quite false naiveté: ‘You are just like all the others!’ And he admitted with the utmost gravity that he was.

Following that visit Bertrand Russell wrote:

31 Sydney Street, Londom SW

My dear Joan (may I call you so?)

I am telling the booksellers to send you a volume of Tchekov and also a tiny volume of my own. If you like the former, there are 11 more like it. I haven’t much time as I go to Leicester today and Bristol tomorrow, but then my public jobs are done.

Saturday of next week I go to Cornwall for the whole summer – then to America for oct and nov. After that I shall live in Petersfield, where my wife and I are starting a school – but from there I shall come to London about once a week. If you think it worthwhile I should like to keep in touch with you by letter, so that when the time comes I can see you again. And I shall wish to know about your career, if you have time and inclination to tell me. Like other people I am not a free agent as regards where I live – but I shall keep the recollection of my visit to Salisbury, not without hopes for the future.

Yours

BR

Over the next two and half years, although they only met three times, Betrand Russell wrote her over twenty letters, becoming more enamoured and insistent as the correspondence between them flourished. The letters became a much-hinted-at, never-revealed and half-doubted secret throughout our childhood and youth until Joan produced the yellowing bundle in the late 1960s with a view to selling them after Russell’s death to the highest bidder to provide some security for her old age. (The full text of the correspondence between Bertrand Russell and Joan Follwell is appended to this memoir by kind permission of McMaster University, Ontario, Canada, who also generously furnished me with copies of four letters in their Russell Archives from my mother to Lord Russell.)

When she parted with the letters in March 1971, she included the following note:

Now after forty years and while these memories of Russell are still vivid in my mind and realising that I am uneducated in the academic sense, but having lived, loved, suffered and received certain intimations of immortality, I consider Russell’s philosophy, as St Thomas Aquinas said of his own, ‘so much chaff’. He believed to his dying day in the perfectibility of man; he believed that, ‘if only’ this and that, man might progress to a sort of heaven on earth. Even H.G. Wells recanted from this kind of thing when he wrote ‘Man at the end of his Tether’ and died in enlightened despair.

Russell, I believe, will be read because he was a great writer and, if ‘Le style c’est l’homme’, he was a great man. As for mathematics, they are surely what makes the world go round – the stars in their courses, the music of Bach and great architecture. Russell glimpsed all this yet stubbornly refused to see the implications of his insights. He might be compared to Pascal, only Pascal was ‘given’ (I use the word advisedly for these graces are gratuitous) to see beyond logic and to experience the ineffable.

This then was the woman whom I knew simply as my mother. Her secret life, her regrets, her unfulfilled dreams, were unknown until I began to piece them together in this memoir. To be sure Bertrand Russell was a household name in the family, but as an almost mythical historical figure and not a very interesting one at that. Even when I finally read ‘The Letters’ in the late 1960s I was conscious of a faint disgust with more than a dash of pity for the naive girl being ‘groomed’ as Russell’s objective in writing to her might be interpreted today. The fact that this period, in her eyes, was the pivotal experience of her life now arouses not only pity, but also a sense of anger. Anger at the society of the time, what Joan refers to scathingly as ‘the bourgeois middle class of Ireland’, which imprisoned her within its rigid rules of acceptable behaviour for married women. But also anger at Joan herself, who reflects through her sporadic writing and her confidences to me in later years – someone vain in her intellectual isolation who, as the years went by narrowed her horizons and confined her aspirations to communing, vicariously through her reading, with the ideas, philosophy and lives of contemporary and long-dead mystics, writers and poets.

Growing up I garnered the flotsam and jetsam of her inner life through the books on the shelves, the books I went in and out to Switzers Library in Grafton Street to exchange for her, and half remembered musings addressed to me, looking up from her book during shared evenings in Leeson Park in my teenage years. St John of the Cross, Thomas à Kempis and Simone Weil formed the backbone of her reading in mysticism, while Francis Thompson’s The Hound of Heaven sat side by side with Tennyson and The Secret Life of the Little Flower by Henri Gheon on her bedside table. Isak Dinesen was much admired but Jean Rhys she thought of as a fellow pilgrim as she did Emma Bovary, reading Flaubert’s French with some difficulty. She read Proust in translation as she did Colette’s Chéri and The Last of Chéri, a slim Penguin edition inscribed to her by my cousin Hugh Carton. Fiction writers of her own era, Henry Green’s Loving, David Garnett’s Lady into Fox and Man at the Zoo, twinned in one volume (a rare one that I read and enjoyed myself at the time), Elizabeth Bowen, Elizabeth Taylor, L.P. Hartley, Graham Greene, one of the few who can still be found on library shelves. Her two heroes, most often read and most often quoted were Boswell’s Samuel Johnson and Henry James although late in life she rediscovered with relish Little Dorrit and Bleak House and found spiritual comfort in Beckett. One of her last notes in 1970 after seeing a Gate production of the play typifies her lifelong sense of the divine:

The clue to Beckett is in Happy Days and the clue in Happy Days is ‘O Happy Chance’. This play is about the dark night of the soul and Marie Keane hadn’t a clue but Ozzie Whitehead was wonderful. Dr Johnson hadn’t the advantages of Beckett, for which he is to be honoured and pitied. His faith was blind and groping and he feared the wrath to come. In contrast Beckett’s characters seem almost happy – they know Godot will come – they are souls in Purgatory and purgatory is a happy state reserved for the faithful soul, just as in Happy Days, Winnie, though up to the neck, is able to console herself with the long littleness of life because HE is there: ‘once seen, never forgotten’ O, the beauty of the ordinary phrase!

Sadly, always waiting in the wings but never valued in Joan’s ‘field of dreams’ was her husband Power. Yet they stayed together, each faithful in their own way but unable to communicate. Joan summed it up:

I read in Graham Greene’s new volume of short stories: ‘I could have explained that nothing is quite so bad as that at the end of what is called ‘the sexual life’ the only love which has lasted is the love that has accepted everything, every disappointment, and every betrayal, which has accepted even the sad fact that in the end there is no desire so deep as the simple desire for companionship,’ It was like a knife in my heart.

That same knife must have also been embedded in Power’s heart but he did not have Joan’s gift of self expression and I can only paint the man, the husband, the father as he was seen by others, including his third daughter, myself.

2. Searching for my Father

Compared to my mother, my father had always been a shadowy figure, coming to life most vividly in memories of early childhood. I remember screaming with fright and delight when he threw me up in the air – pretending to miss on the way down but always just catching me in time. Like all fathers I thought him the most handsome man in the world. Randolph Scott was my first movie hero; I was convinced he resembled my father and wept loudly when a black-clad cowboy smashed his good gun hand during one harrowing showdown: fortunately he recovered in time to shoot down the baddie in a fair fight on one of those eternally deserted main streets of the black-and-white Western towns that were featured week after week of Saturday matinees at the Savoy Cinema on Bedford Row, Limerick.

For a special outing my father brought me to the O’Mara Bacon factory to see black puddings and sausages being made. It was a tour of Dante’s Inferno: great black cauldrons full of liquid that looked, smelled and probably did consist mainly of blood – the stench was horrific and if there is such a thing as an aural memory I have it of squealing pigs wired up for slaughter. Another treat was to visit the shop and go up the ladder to the little glass box at the side where the lady sat and where the cash canisters came whizzing up the wires. She would unscrew them, take the money and docket out, put back in the change and send it whizzing back down to the shop man below.

Daddy had a gold watch and chain that had been given to him by his father, the great tenor Joseph O’Mara, one of the last relics of the carefree days before it was sold to alleviate one of our many financial crises. Other clear memories of my father are associated with Kilkee, where like all decent Limerick people (except for those few heathens who went to Lahinch) we spent as much as possible of the summer in temporary residence. Our preference was for the West End. We had a cottage on the Dunlica Road where a major event in our weekly routine was the placing of a big tin bath in the middle of the kitchen floor that was filled with kettles of boiling water heated on the range and cooled by cold water from the pump outside.

In the same kitchen I was the fascinated observer of the doctor bent over my sister Mary’s bared bottom, extracting long black porcupine spines with some instrument of torture to the accompaniment of her shrieks and sobs. The porcupines were denizens of the Pollock Holes, natural swimming pools among the rocks at the bottom of the cliffs where Mary and Ruth had both learned to swim.

I remember being my father’s sole companion on our hugely enjoyable visits to Scott’s Bar, where there was a large oval mirror with a picture of two Scottie dogs, one white and one black. I was treated like a little Princess (his pet name for me) and put up on a high stool and given a tall glass of fizzy lemonade with ice cubes and tiny bubbles floating on top. He usually had a small glass of whiskey with some soda that I was allowed to squirt from the big bottle on the counter. On the way home, as a special treat, he would buy me a newspaper cone of periwinkles which had to be angled out of their shells with a pin. They tasted deliciously like snot.

Again as a small child, clutching Daddy’s hand tightly crossing over Sarsfield Bridge in the dark. We were in the midst of crowds of people milling around: cheering voices, bright lights, torches held aloft and a mysterious fervour in the air. A band, rousing music, ‘A Nation Once Again’, ‘Amhrán na bhFiann’. It was 1949, the celebration of the Declaration of the Irish Republic. What was in his mind, I wonder? I never recall him alluding to his early experience or making any claims of patriotic activity while others secured jobs and influence as freedom fighters for Cathleen Ni Houlihan.

Who was this father, beloved in my childhood, ever more distant as I grew up, who was born to the arias of Puccini at the dawn of a new century in London, and who died as quietly as he had lived in an anonymous hospital ward in the same city, just as the Beatles were sweetly and slyly revolutionizing popular music in the swinging sixties? It took me another forty years to find out.

James Power O’Mara was born in London on 21 May 1900. He was the second child and eldest son of Joseph O’Mara, a well-known tenor with a successful career on the operatic stage in London and as an international concert performer. His mother was Brid Power from Waterford and, as was often the custom, her maiden name was taken as Christian name by the eldest son. His grandfather James O’Mara had migrated from Tipperary to Limerick in the late 1830s and founded the O’Mara Bacon Company. Joseph O’Mara, the youngest of his thirteen children, was born in 1864 when the family business was already established as the leading bacon-curing company in Ireland and the family had rapidly climbed the social ladder to become leaders of the new Roman Catholic merchant class. By the early twentieth century O’Mara Bacon had subsidiaries and partners in the USA, Canada, Romania, France and Russia, where an elder brother of Joseph’s, Jack O’Mara, had built a bacon factory in St Petersburg by commission of no less a personage than Tsar Nicholas II. The head of the family by then was Joseph’s eldest brother, Stephen O’Mara, driver of the family’s business expansion, and twice Mayor of Limerick, who had refused to host a civic reception for the visit of King Edward VII and thereby renounced a baronetcy. In 1900, a few years prior to the aborted royal visit to Limerick, his own son James was elected to Westminster as a Redmonite MP for the constituency of Kilkenny.

Joseph O’Mara appeared to break the mould by running off to sea at eighteen. Having got the wanderlust out of his system, and, on inheriting a small bequest from his godmother and secretly attending an audition in London, he announced at nineteen that he was going to study singing in Milan. His bemused parents apparently made no objections to this scheme and so his career was launched. Although leaving few recordings and reputedly disliking the embryonic technology, his quality as one of the foremost tenors of his age is well documented. He sang all the classic major roles in the leading opera houses of the day, including seasons in Covent Garden, touring extensively in the USA and Canada. He subsequently turned impresario as well as performer when he formed The O’Mara Opera Company in 1910. The family annals include letters from Nellie Melba, a contemporary and friend, such as the following undated note:

30 Cumberland Place

Dear Mr O’Mara,

I am afraid you took what I said ‘au serieux’ yesterday which was very wrong of you as I only said it for fun. I am one of your most enthusiastic admirers and I always say nice things about you to all sorts of people.

I am quite upset that you should have felt hurt because I did not mean what I said. Please drop me a line to say that you understand and please don’t get huffy again.

Yours sincerely

Nellie Melba

P.S Come and see me

John McCormack, twenty years his junior, wrote to his widow after his death to say that Joe had been his guide and mentor, and telling how he had queued in the rain as a young man outside the Gaiety Theatre for the thrill of hearing O’Mara sing the title role in Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet. Oddly, although McCormack was by then the better known, it was Joseph O’Mara who was invited to sing for the first transmission of Raidió Éireann on 1 January 1926.

In everything other than his unorthodox choice of profession, Joseph and Brid O’Mara remained true to their roots. Family life was conventional and retained all the traditional values of Catholic Ireland. For the first fifteen years of Power’s life, they lived in England. Power and his younger brother Joe went to Stonyhurst College, the renowned Jesuit public school, and thereafter to Belvedere College, another Jesuit private school in Dublin when the family finally moved back to Ireland, presumably for reasons connected with the First World War, when overseas tours and opera performances in London were curtailed.

As a young man during those chaotic years in Irish history between 1916 and 1921 Power aligned himself firmly on the Sinn Féin side. Whereas his father Joseph showed no interest in the emergent Irish nationalist movement, the Limerick uncles and cousins were very much involved. It is from that branch of the family that Power gained his enthusiasm and association with the ever-hastening pace of political and revolutionary activity. His first cousin James O’Mara, who had resigned his South Kilkenny seat in Westminster, stood as a Sinn Féin candidate in the same constituency in 1918 and won a landslide victory. He is proudly featured in the classic black-and-white photograph of the meeting in the Mansion House of the First Dáil in 1919.

However, unlike his uncles and cousins so firmly committed to constitutional politics, Power O’Mara took the road of armed rebellion and secretly joined the IRA. An account of his involvement in an ambush of a British army armoured car during the War of Independence was given by his sister Eileen O’Mara Carton after his death:

It was a foggy afternoon in November 1919; we were having tea in the drawing room when my brother Power came in looking for Joe who hadn’t yet come home from school. I wondered why he seemed so restless and upset, even more so when at last Joe appeared, bursting with some tale of mayhem in Dorset Street, Power became suddenly infected with high spirits, grabbed Joe in a bear hug and galloped him down the room.

Six months later I learned why: Power had secretly become involved in the War of Independence. On that November day, he had been stationed at the corner of Findlater Street waiting for a convoy advancing from O’Connell Street. At the very moment he flung the Mills bomb towards a passing Saracen car, he saw his brother Joe on his bicycle crossing the intersection on his way back from lunch to nearby Belvedere College. It wasn’t until Joe walked into the room four agonising hours later that he knew whether or not his brother had survived.

However, a few months later another skirmish resulted in Power being wounded, which brought his subversive activities to the ears of his shocked parents and his hurried departure to a new life in Canada. Whether or not he was a willing or reluctant exile is not known. It was a period of his life he never spoke about, and, until this memoir, the twenty-year gap between his exile to Canada and return to Ireland in 1940 was never explored or explained. He was taken in by another first cousin in the innumerable O’Mara clan, one Joe O’Mara, who had settled in Canada some years before to manage another offshoot of the O’Mara bacon empire in Palmerston, Ontario. This cousin – the family entrepreneurial flame well alight – also established a rubber-tyre factory, K & S Tire and Rubber Goods Ltd in Toronto, where Power was working in early 1926, according to a long and affectionate letter to his parents about this time. Had the rubber business flourished Power might well have remained in Canada for the rest of his life but in the late 1920s British control of the rubber plantations in Asia pushed up the price of rubber in the US and Canada and the business failed. He returned to Ireland briefly to register the death of his father in Dublin in October 1927.

The next official record is of his marriage in 1932 in Salisbury, England, to one Winifred May Follwell (her old-fashioned Christian name long rejected in favour of Joan), born in Bristol on 13 May 1906. Her wedding on the same day twenty-six years later provoked headlines in the local newspaper: SALISBURY BRIDE DEFIES SUPERSTITION, referring to the double jeopardy of marrying on her birthday, dressed in green. The same newspaper clipping describes the occupation of the groom as ‘Factory Manager, Melksham’, the only clue to where and how they met, as Joan’s last letter is written on headed notepaper from the Avon India Rubber Company, Melksham. Given Power’s recent employment in the rubber business in Canada, it is not unreasonable to suppose they met each other through work, but whether he is the lover Joan refers to in her correspondence with Russell remains an unanswered and intriguing question.

Whatever the gamble, it appears their first few years of married life were both happy and prosperous as evidenced by the salubrious neighbourhoods of their first homes, in Cheadle Hume, Manchester, and Richmond, Surrey. But the outbreak of World War Two changed all that. In 1940 Power, a pregnant Joan, with their daughters, Mary Elizabeth and Ruth Winifred, aged seven and five, dressed in ‘siren’ suits with labels round their necks, were evacuated to Ireland. All their possessions were lost in the London Blitz apart from an old travelling trunk containing the family silver and precious memorabilia of Joseph O’Mara’s operatic career. Both his parents were dead, Joseph in 1927 and Brid in 1935, so it was the more distant Limerick family of uncles and cousins, deeply embedded in the family tradition of business and civic duty, who offered asylum to the refugees from war-torn Britain.

In Limerick Power took up a position with the family firm, the O’Mara Bacon Company. Their third daughter, myself, Eileen Thérèse, was born there on 15 January 1941. Nineteen forties Ireland was radically different to the revolutionary fledgling republic Power had left twenty years before. De Valera’s neutral Free State was a closed society where Church rather than Empire held sway over a rigidly conservative and economically protectionist political system. The re-entry seemed to have been a painful transition for both Power and Joan and they endured a peripatetic life for the first year, largely apart. Several loving letters from a lonely Power, working for far-flung O’Mara outposts in Claremorris, County Mayo, and Letterkenny, County Donegal, attest both to his love and loneliness.

He was torn between having to work away from home – ‘if only I could get a settled job someplace’ – and his worry about Joan, who was moving from Limerick to remote Kilkee, apparently in escape from family pressures. Another letter speaks volumes of both his homesickness and the sexual mores of the day.

I am longing to see you and will take the first opportunity of getting away for a weekend. A rather embarrassing question if we are to start this ‘Rhythm’ business you will have to let me know when I can make love to you. I doubt if I could withstand the temptation otherwise. Are you still nursing Eileen once or twice a day or is she on the bottle altogether now. Isn’t she lovely in the enlargement?

A telegram sent from Letterkenny on 13 May 1941, the ninth anniversary of their marriage, says it all: ‘Many happy returns heartfelt gratitude past nine years. Love Power.’

Some months later he finally landed that ‘settled’ job as manager of the O’Mara retail store Rays Limited. Limerick was to be their home for twelve years, beginning in hopes for a new life, a new job, a new child, the first to be Irish-born. The city proved a harsh introduction to the Ireland of saints and scholars for Joan, erstwhile lover of Bertrand Russell, unredeemed socialist, unorthodox convert to Catholicism. When the family moved to Dublin in 1953 she, at least, was not unhappy to shake the dust of Limerick’s shibboleths from her elegant ankles as she left for a shabbier but more contented life among the left-wing literati of Dublin town.

3. At Home

The basement – a cavernous kitchen and scullery, the vast black range and red flagged floor; bread and dripping, delicious if you were allowed to dig down to the beefy jelly at the bottom of the bowl; sticky spoons of Cod Liver Malt to make you strong; golden syrup – the green and gold tin had a picture of a lion on it with the words ‘out of the strong comes forth sweetness’. The first banana ever tasted, a bit slimy – strange but delicious. Apart from the ceremonial stirring of the Christmas pudding when I was allowed to drop in silver thrupenny bits with the little rabbit on them and scrape the bowl afterwards, I have no recollection of my mother ever being in the kitchen at all. Later recall of a vast dog-eared tome entitled Mrs Beeton’s Cookery Book, which followed us from house to house leads me to believe that Mother did in fact cook but, as it was in her eyes a chore rather than a pleasure, meals, other than grand Sunday lunches, never took on an aura of nostalgia.

The kitchen stairs led up first to the hall return where the playroom led out to the wooden landing and rickety stairs down to the back garden – featureless like every garden our family had apart from a swing constructed on strong timber stakes and the two lilac trees at the far end, which flourished against all the odds, their fragrant purple blooms hanging just within range of your toes on the upmost arc of the swing during the long spring and summer evenings. A couple of shallow steps up from this grown-up-free zone lay the dining room. Here was the brilliance lacking in the kitchen: all gleaming mahogany, table, sideboard, serving trolley on wheels, the family silver laid out, carelessly opulent, carefully polished with all the reluctant effort of the Silvo-stained fingers that took on the mammoth task in sibling disharmony. Because they so suddenly disappeared from my ken, my visual and tactile memory of these symbols of prosperity that adorned the sideboard is still vivid. A great serving dish with entwined handled lid, the soup tureen and ladle, sat on the large silver tray inscribed with the family crest, a winged bird of prey with the motto ‘Opima Spolia’ over the script: TO BRIDE AND JOE, FROM FATHER, JUNE1896. On the smaller more ornate tray nearby lay the silver service of tall coffee pot and round tea pot, milk jug and sugar bowl with tongs, all resting on lion-headed, clawed feet. The table itself was covered in white, sometimes embroidered white cloth where my father presided, all bonhomie and jokes, armed with the large bone-handled carving knife and fork; he always made a ceremony of sharpening the knife on the steel with much flourishing before tackling the joint of beef or even roast chicken for special occasions. Pièce de résistance of the feast were the roast potatoes served last from a big china bowl, to be lathered with rich brown gravy from the gravy boat.

The drawing room was at the entrance of the house to the immediate right of the front door, which opened on to a long flight of granite steps, a shrine to scraped knees and scenes of great lamentation when my mother was seen departing in one of her elegant suits and turban hats. The heart of the house lay here, certainly not in the dungeon kitchen. It was large, comfortable and untidy. A big sprawling settee (‘sofa’ was non-U); two deep armchairs and a couple of worn leather poufs; a glass-fronted cabinet with its precious and long-gone collection of Crown Derby and hand-painted fruit dishes. Bookcases, also with glass doors, each with a tiny key; the books seemed very dull and heavy with no pictures: ‘and what is the use of a book’ thought Alice ‘without pictures or conversation in it’ although there were some rows of slim red and white Penguin paperbacks that seemed more like my own fastgrowing Puffin collection. The mantelpiece had my favourite delicate Dresden monkey-headed shepherd alongside his shepherdess. I can see her exquisite pink-figured looped gown to this day – they met an awful fate smashed on the fireplace in another house one grim day a few years later. Lastly, a handsome round mahogany sewing table, whose top opened into compartments overflowing with darning wool, reels of cotton, odd socks and knitting of various colours and dimensions.

Three pictures informed and enthralled my budding visual consciousness: an old beshawled crone, sitting upright on a wooden rocking chair – it was by William Conor, given away in later years by my mother as a wedding present because she had no money to buy one; a glowing silver and black ‘Frozen Pond’ by George Campbell – this too became a wedding gift to my sister Ruth in 1971. The third was an impressionist view of the backs of houses at Ennistymon by Grace Henry. I was convinced as a child that a human leg was hanging out of one of the windows until I saw the selfsame picture at an Adams auction fifty years later and realized it was part of a line of washing.

The bedroom interiors are vague, perhaps because I never inhabited any of them except when sick with measles or pneumonia when I was upgraded from my attic abode to my mother’s bedroom. I remember tiptoeing past its closed portals in the mornings so as not to disturb her before the sacrosanct cup of tea was imbibed in the shadowy dimness of that holy of holies, where even my father trod quietly. Sometimes I would be called into the darkened room before leaving for school to give Mummy a kiss. I hated the gloom and Mummy’s face, shiny with Nivea and bloodless lips, so unlike her daytime soft powdered cheeks and bright lipsticked mouth.

Up again lay the attics, plural as there were several partitioned-off rooms within that spacious roof space. Years later, driving down the Ennis Road as an Irish Tourist Board recruit en route to Paris, I could still distinguish the house by the wooden bars on the front attic windows. A Christmas Eve in the 1940s: I wake up in the dark, a beam of grey moonlight coming through the skylight shows a limp stocking hanging on the end of the bed. I hear footsteps coming up the stairs and squeeze my eyes tight shut in case Santa would discover I was awake and leave the stocking empty, the latch lifted, stealthy sounds followed, the door shut quietly and when I got up the courage to look – lo and behold the stocking was bulging with interesting shapes. I was able to maintain with the absolute conviction of the true believer that Santa did exist long after my friends had lost their own more precarious faith.

There were eight years between myself and my eldest sister Mary, who was two years older than Ruth. To all intents and purposes it was a generation gap. Mary was away at boarding school in Roscrea from the age of eight, and early memories of her are fraught with strange events and whispered secrets. I was four when she was sent home from school in the middle of term and in disgrace – Mary had told the nuns she had swallowed a safety pin and not being sure whether it was open or shut she was sent home so that her family would have the dubious pleasure of examining her bowel movements for several days after the event. No evidence was ever found but Mary got an extra week’s holiday for her trouble. But however difficult her reputation at home or at school, Mary was my protector and as glamorous as a film star. When I too was sent away to Roscrea at the ripe age of seven, she became my one beacon of hope, the only certainty in a world of black-robed warders, mocking co-prisoners, strange rituals and inedible food.

Although I recall my soujourn in Roscrea as interminable, I had only to endure the two-month summer term of 1948 to prepare for my First Holy Communion. My mother’s more ascetic form of spirituality found the showy and materialistic celebration of children’s first communion in Ireland when neighbours’ children visited their friends and relations on the big day to be given half crowns at least, vied with each other and boasted of their wealth, quite shocking. It was anathema to the English ex-Protestant, still devout convert with a particular devotion to the spare mysticism of the Little Flower. So she determined that her youngest daughter would go to the altar unsullied by the paganism rampant in the Holy Confraternity City of Limerick. I survived to the glorious day in June, when, arrayed in my cousin’s borrowed long white bridesmaid’s dress and veil, I kneeled, with only one other, on prie-dieux at the steps of the altar. My only conscious prayer was that I wouldn’t faint and have to come back for a rerun. All was sweetness and light afterwards with tea and cakes in Reverend Mother’s parlour. My horror when she bent down to pinch my cheek and tell my mother how good I was and how I must be let come back again next term – was there a pause or did my mother see my imploring, desperate eyes? In any event my sentence was over. Mary had two more years to serve.

Where was Ruth in all of this, the middle sister, the quiet one, the solid citizen, not wild like Mary, not a princess like Eileen? In my eyes Ruth was ‘she who must be obeyed’. I longed to be allowed play with her, or better still have her play my games – playing ‘house’ was my passion, a continuing saga involving complicated role-playing. The playroom on the return in Moyola Terrace was the terrain. Pushing the trestle tables around to form various rooms, journeys were undertaken with bundles of rags stuffed into pillowcases known as ‘burdens’, which had to be carried up and down stairs, a tribute perhaps to Pilgrim’s Progress. Playing house must have been real agony for Ruth because she was the quintessential tomboy: her best friends were boys and she read only boys’ books.

My debt was largely repaid by frequent trips next door to borrow Louis’ comics. As well as The Hotspur, there was TheChampion, The Rover and of course TheDandy and The Beano, so I escaped the saccharine doings of Girl’s Crystal and School Friend for the much more thrilling adventures of Rockfist Rogan, Desperate Dan, Wilson, the Boy Runner, and Ginger Nutt, the Boy Who Took the Biscuit. Later I graduated to Biggles and Just William and I am grateful for this apprenticeship in male sportsmanship before I fell under the spell of Enid Blyton, the Chalet Girls, and Angela Brazil, whose jolly hockey sticks never held quite the same mystique for me as Teddy Lester, Captain of Cricket. This robust fare mixed happily in my imagination with my mother’s diet of the Green, Yellow and Red Fairybooks with Andrew Lang’s beautiful illustrations, the Water Babies, The Princess and the Goblin, The Did of Didn’t Think and the Victorian tear-jerker Froggy’s Little Brother.

She was an expert tree climber while even then I was scared of heights. If I got stuck Ruth would get into trouble if adults had to be called on to rescue me. I must have been a serious pest. She had to take me out for walks too – one time we went as far as Barrington’s Pier and back along the river, a lonely windy path, me with the doll’s pram and Ruth pulling me along faster and faster because of the funny man who kept walking alongside us and whispering or whistling, I’m not sure which. He had a long raincoat and then he had his trousers open with his willy hanging out. Ruth never said a word, just went faster and faster until we got to Rose’s Avenue and he went away. We never said anything about it at home.

Next door was like going into Alice Through the Looking Glass country, the same rooms back to front but occupied by the Keane family. I was always made very welcome but had to brave the fearsome ‘Manger’, the big Alsatian dog, who lurked behind the kitchen door and growled sullenly as I edged by. Reputedly, Manger – or more likely Major – loved children, and although I pretended equal affection when led up to pat his head, his yellow eyes and raised hackles sent me a very different message. Unlike some of our other neighbours the Keanes were not posh but presumably rich because they owned a motor car and used to bring me to Kilkee for the day, an expedition of forty miles there and back. We always stopped en route at Fanny O’Dea’s for red lemonade where I would gaze wonderingly at the big hearth where I was told the fire had been lit one hundred years ago and never gone out since. I sat on Marie’s knee in the back of the car, which was better than sitting on Father Scanlon’s knee. He was fat and jolly with a red, perspiring face and often came for tea on Sundays in the Keanes’ drawing room where Marie played the piano as he led the singsong. These occasions joined the Manger-type of pitfalls to be avoided if at all possible. How to avoid sitting on his lap became a study in juggling politeness and obedience with discomfort and embarrassment. When the former won, I perched stiffly on his knee while his stubby fingers edged inside the elastic of my knickers and touched my ‘botty’. I always jumped down as soon as I could, but never told anyone; it would have been too rude.

4. The Outside World

Across the road lived the Cross, Sexton, O’Malley and Duggan families, a little further along the Harrises and the Treaceys. For some time Grace Cross was my best friend. She lived in the corner house opposite, beside the crossroads. My earliest effort at English composition went thus: ‘Grace Cross at Union Cross is very Cross.’ She was a fearsome little girl with blond curly hair and bright red cheeks. When we first met she was three to my five but she was always much stronger and bossier than I and took complete charge of our playtime together. On one occasion she would not let me go home and straddled her front doorway on her fat little legs, arms akimbo, defying me to pass. We used to play doctors and nurses in the old shed at the back of her garden, taking a great forensic interest in our bottoms and tummy buttons. I fancy this must have been at my suggestion as I got a nurse’s outfit one Christmas complete with apron, cap, bandages and red ink iodine with which we painted each other’s arms and legs.

The other families within our immediate neighbourhood had less impact on my own small world. Their children were older, closer to my sisters’ age, but certain vignettes remain with me still. The Sextons all had red hair and Rosemary Sexton was at my school and died. I report this baldly because it is all I was told; the horror mixed with awe that someone I actually knew was dead. The O’Malleys were a distant presence: there was a Jane O’Malley whose uncle Donogh was a friend of my father’s. He became a popular Minister for Education in the 1960s and is credited with bringing in free secondary-school education for all. He died young and I remember being introduced to him in a pub in Molesworth Street as a teenager by my father. He had been instrumental in getting my father his IRA pension when family fortunes were on the downward slide. My mother’s few remaining papers include one from the relevant authority refusing to continue the pension payment of £2 a week to her after his death in 1967. Next came the Duggans, reputedly very rich but vulgar, not quite approved of by the more genteel if less well-off neighbours. The Treacys, whose daughter Marion was in my class in Laurel Hill and whose tawny, curly hair and pert pretty face I admired enormously was the reincarnation of Rosie Redmond in What Katie Did Next. The Harrises seemed to be all boys, – large, wild boys. One of them was my sister Mary’s particular friend, the first boy who ever kissed her, Dickie Harris, known in later life as Richard Harris. How she impressed her English granddaughters when she confided that Professor Dumbledore, was her first boyfriend!

Although also on the Ennis Road, Strand House. home of the head of the family Stephen O’Mara, and his wife Nancy, seemed quite a long walk from our house towards town, although a nostalgic retracing of the same route fifty years later hardly took five minutes door to door. It was here that De Valera was staying when he received news on the signing of the 1921 Treaty in London. The large house was of a warm yellow hue with a terracotta tiled roof and jutting eaves. Going to tea there on summer afternoons lives in the memory like a scene from a Merchant-Ivory movie: the conservatory with cane cushioned chairs, china tea set and delicately cut bread and butter, scones with jam and cream and, oh bliss, chocolate finger biscuits. Uncle Stephen was much older than Daddy, with thick greying black hair, dressed always in tweeds. Aunt Nancy was gracious and elegant with gentle blue eyes and long hair beautifully arranged in a chignon. Their adopted grown-up son Peter, was a great admirer of my mother. They became soul mates in the intellectual desert that was Limerick at the time and swapped books of poetry and banned novels, of which there were many. Sometimes Nancy’s sister Kate O’Brien was there – according to whispered family legend she was Peter’s real mother, severe in comparison to her feminine sibling.

But it was the gardens rather than the humans that were the true delight; to reach them you had first to pass the lily pond with stone lions at either end and peer under the perfect ivory and yellow blossoms floating on their green-petalled crafts, to catch a flash of the swift gold and crimson fish darting about beneath. Then out to the carefully controlled wilderness of the kitchen garden, picking strawberries and gorging on their sweet juiciness, gooseberries too, all bristled and plump yellowy green; the first and last time I ever saw or picked peaches from a vine trailing up a sunny wall.

I thought I had imagined or perhaps invented those peaches until I read Patricia Lavelle’s recollection of Strand House in her biography of her father, James O’Mara:

There was a paddock of several acres between the house and the high boundary wall that cut out the road from the river. There was a kitchen garden with peach trees growing on a nine-foot southern wall. There were glass houses with melons and grapes and plenty of stabling.

The first external stimulus was the radio – the handsome polished brown Pye wireless with all the twiddly knobs and mesh front. Listen with Mother