Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

All they wanted was land: land for crofting and land on which to build a house. In 1908, ten desperate men from the islands of Barra and Mingulay in the Western Isles were imprisoned in Edinburgh for refusing to leave the island of Vatersay, where they had built huts and planted potatoes without permission. The case caused an outcry throughout Scotland, and led eventually to the purchase of the island by the government for crofting. This book, the first about Vatersay, tells the remarkable story of the raiders and their struggle to escape from the poverty which the policies of an absentee landowner forced them to endure. The Vatersay Raiders documents not only these events, which had enormous significance in the history of crofting, but also the fascinating earlier history of Vatersay and its now-deserted neighbour Sandray. An outline of more recent developments brings the account up to date.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 332

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Vatersay Raiders

To the memory of John MacInnes (1946—2003) of Edinburgh, whose painstaking research into his ancestors in Berneray and Barra revealed much new information on the Barra Isles, which, it is hoped, will one day be published

This eBook edition published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2008 by Birlinn Limited

Copyright © Ben Buxton 2008

The moral right of Ben Buxton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-84158-112-3 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-492-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Contents

List of Illustrations and Maps

Foreword and acknowledgements

Prologue: ‘An extraordinary proceeding’

1. Early times

2. Tacksmen, landlords, tenants, 1549–1850

3. Farm and shipwreck, 1850–1900

4. Early raids, 1900–1906

5. The invasion, 1906–1907

6. The trial, 1908

7. Purchase and division, 1908–1909

8. Establishing the community, 1910–1913

9. Since the raiders

References

Bibliography

Maps

Appendices:

1. Chronology of the raids and main people involved

2. Vatersay population figures

3. Nan MacKinnon and oral tradition

4. Song for the raiders

5. Song to the Annie Jane

6. Names of children and staff in the Vatersay School photograph

List of Illustrations and Maps

Illustrations

1. View of Castle Bay, Barra, and the islands to the south.

2. Lady Gordon Cathcart.

3. The herring curing station on Bàgh Bhatarsaigh in the 1870s.

4. The eastern end of the herring station.

5. The raiders’ huts on the site of the present township of Vatersay, in September 1908.

6. As above, looking towards Barra.

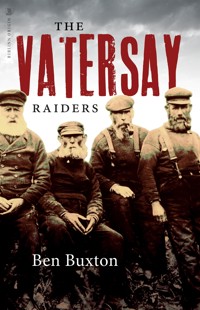

7. The ten Vatersay raiders, with their two legal advisers.

8. Vatersay Township in 1927.

9. Vatersay House and Township in 1948.

10. The eastern part of Vatersay Township in 1949.

11. Vatersay Township in 2006.

12. The ruins of Vatersay House, 2006.

13. Bringing home the hay across the machair in 1948.

14. Nan MacKinnon, who was celebrated for her knowledge of Gaelic oral tradition.

15. Donald Campbell (‘Thomson’), postman, at Uidh in 1952.

16. The Church of Our Lady of the Waves and St John.

17. The interior of the church as it was originally.

18. The pupils and staff of Vatersay School in about 1935.

19. Vatersay School and Schoolhouse.

20. A puffer on the beach of Bàgh Bhatarsaigh.

21. Caraigrigh, Uidh, from Creag Mhòr.

22. Peggy MacLean.

23. Caolas in 1948.

24. The first car ferry to Vatersay.

25. Maggie, James and Flora Gillies stacking hay.

26. The causeway linking Vatersay and Barra.

27. Eorasdail in 1948.

28. The township of Eorasdail today.

29. Mingulay Village in decay in August 1909.

30. Houses in Mingulay in August 1909.

31. Sarah MacShane and her remaining pupils outside the schoolhouse in August 1909.

32. Remains of the shepherd’s house east of Bàgh Bàn, Sandray.

33. The Sandray raiders, who were all from Mingulay, at Sheader in October 1909.

34. Neil, Maggie and Flora Gillies at Sheader, October 1909.

Maps

1. The Barra Isles.

2. Vatersay.

3. The area around Vatersay House and Farm from the Ordnance Survey Map of 1901.

4. Castle Bay, Barra, around 1900.

Foreword and acknowledgements

‘Vatersay may yet become a place famous in history,’ claimed a newspaper writer in February 1906. This prediction turned out to be prophetic: Vatersay did become famous, more so than other cases of land being raided by land-hungry cottars. One hundred years on, the raiders remain famous in Vatersay and Barra, but other raiders of farms in Barra have long been forgotten. The Vatersay raiders are regarded as heroes in their own island, having fought for and won the land still occupied by their descendants.

It is something of a paradox that, having been so well known at the time, the remarkable story of the raiders has never been told in any detail in print. Various authors have included the raiding of Vatersay in accounts of the Barra Isles or in wider studies of land raiding and crofting. These authors have had access to the voluminous records of the Congested Districts Board and the Scottish Office, but because of the vast amount of documentation, they have seen only some of them. While researching among them for this book, I became aware of deficiencies in my own account in Mingulay, an island and its people (Birlinn, 1995). Even now, I cannot claim to have seen all the records, but, using other sources such as newspaper articles, oral history, and the work of authors who have had access to other archives, I am hopeful that my account is accurate. I have had to be selective in what I have used in the chapters on the raiding and settlement, also in the brief account of the subsequent history.

Being non-resident I have not been able to make full use of the vast amount of knowledge among the present people of Vatersay and Barra, and being a non-Gaelic speaker, I have not been able to make full use of the tape recordings of past inhabitants made by the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh. I hope that, some day, somebody may make more use of these than I have.

I was inspired to write this book because I felt it was important to document the story of the raiders, particularly because of the approaching centenary of the raiding and settlement. I also felt that the book should include the earlier history of the island, about which very little has been written (apart from the prehistory, which has been investigated, and I have therefore not covered it in detail), and I have outlined developments since the community was established.

Once again I must record my thanks to the people of Vatersay and Barra for their help and support. I am particularly indebted to Mary Kate MacKinnon, and I am also grateful to the following: Donald Duncan and Peggy Ann Campbell; Rhoda Campbell, Morag MacDougall, Michael MacKinnon; Hector MacLeod; Neil MacDonald; Calum MacNeil; Teresa MacNeil; Margaret Nixon.

I am also very grateful to the following for assistance in various ways: Dr Colleen Batey, University of Glasgow; Professor Keith Branigan, University of Sheffield; Edwina Burridge, Inverness Library; Dr Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh; Michael Clark; Professor David Gilbertson; Paul Harding; Andrew Kerr; Bill Lawson; Dr Cathlin Macaulay, School of Scottish Studies Archives; Alastair MacEachan; Paul McGuire; Linda MacKinnon, Castlebay Library; Fiona MacLeod, Highland Archives; Dr Nicola Mills; Andrew Nicoll, Scottish Catholic Archives; Dr Richard Pankhurst, Botanic Garden, Edinburgh; Magdalena Sagarzazu, Canna Archives; Dr Anke-Beate Stahl; Brian Wilson; Maggie Wilson, National Museums of Scotland Enterprises.

The following kindly read drafts of the book and I am most grateful to them for their invaluable comments and suggestions: Caroline Buxton, Dr Ewen Cameron, Mary Kate MacKinnon, Flora MacLeod, Eve Sheldon, Patrick Tolfree. I am of course responsible for any errors.

For permission to reproduce material I am grateful to the following: Canna Archives, National Trust for Scotland, plate 10; Comunn Eachdraidh Bharraigh agus Bhatarsaigh, front cover (by RMR Milne) and plates 4, 7, 14; Donald Duncan and Peggy Ann Campbell, plate 20; Robin Linzee Gordon, plate 2; Mary Ann MacDougall, plate 18; Morag MacDougall, John MacDougall’s account; Neil MacDonald, plates 24, 25; Peggy MacNeil, plate 16; Teresa MacNeil, letters of Neil MacPhee; National Archives of Scotland, plates 5, 6, AF42/5318; The Trustees of the National Museums of Scotland, plates 9, 13, 22, 23, 27; National Trust for Scotland, plates 29, 30, 31 (RMR Milne Album); School of Scottish Studies, plate 15, and extracts from recordings of Nan MacKinnon published in Tocher; Scottish Catholic Archives, plate 3; Lisa Storey, translation of John MacDougall’s account. Plates 33 and 34 are by Dom Odo Blundell. Plates 1, 11, 12, 17, 19, 21, 26, 28, 32 are by Ben Buxton.

Notes to readers:

In Vatersay and Barra the term ‘the raiders’ is used to refer to all those who settled on Vatersay illegally between 1906 and 1908. In this book I use the term for those pioneers who raided in the first year or so, of whom ten were imprisoned. I also use the term for those who raided Vatersay in the years before 1906.

Place-names: for Vatersay and Sandray names which are on the 2003 edition of the Ordnance Survey Explorer map 452, I have used the forms given on that map. Many Vatersay place-names are not on the map, and some of those which are, are inaccurately located. For names in Barra and elsewhere I have used the Anglicised forms in common usage in print, and given Gaelic versions in Appendix 7.

References: to keep reference numbers to a minimum, numbers at the end of paragraphs give references for that paragraph, and in some cases, previous paragraphs. References are not given where the source is quoted in the text.

Prologue: ‘An extraordinary proceeding’

It is 2 June 1908. Ten fishermen from the small island of Vatersay in the Outer Hebrides present themselves before the Court of Session in Edinburgh charged with breach of interdict (injunction) and contempt of court. Their alleged crime: they had refused to leave the island which they had raided – in other words invaded – and on which they had built huts and planted potatoes without the permission of the landowner.

The raiders were from the nearby islands of Barra and Mingulay where they had lived in primitive and overcrowded conditions. They were cottars, that is, people with no crofts (smallholdings) for growing food or grazing their cattle, and some had only makeshift houses. For years the raiders from Barra had appealed to the landowner, Lady Cathcart, for crofts on Vatersay. At the time, the island was run as a single farm, inhabited only by the farmer and his workers. Her Ladyship, who lived in Cluny Castle in Aberdeenshire, and had not visited her island dominions since 1878, had consistently refused requests for crofts on Vatersay, so, in desperation, the raiders had taken the law into their own hands. There had been no violence at any time – although the raiders had acted in a threatening way towards the farmer – nor had there been any police or government action to remove them.

The men had invaded Vatersay in July 1906, and over the following months took up residence. Lady Cathcart had served interdicts on the men, requiring them to leave the island, in April 1907. However, she had delayed further action in order to give them time to leave, and she was in negotiation with the Scottish Office about creating a crofting settlement on the island. She was also in dispute with the Scottish Office because it had refused to take action to remove the raiders. The raiders had defied the interdicts and settlers continued to arrive, undeterred by the threat of legal action. In January 1908, Lady Cathcart served a complaint for breach of interdict and contempt of court on the men.

The trial was to have been on 19 May, but the raiders had written to the court beforehand saying that they did not have the money for their fares, so the case was postponed until 2 June. They added in the letter, ‘we did not wish to defy the court . . . we have every respect for the court but not for our landlord or her advisors . . . she is not to blame so much as they are for she has not been here for 30 years and does not know our real condition.’

There were elements of farce to the raiders’ journey to Edinburgh by steamer and train. To begin with, their fares were paid by their adversary, Lady Cathcart. It is unlikely that any of them had been to the capital before, although they would have been to fishing ports on the east coasts of Scotland and England; unlikely, too, that any of them had been on a train before. They arrived in Edinburgh the evening before their court appearance, but missed the reception party awaiting them. The Edinburgh Evening News of 2 June reported:

Owing to some miscarriage in the arrangements their arrival was quieter than otherwise it might have been. The party of ten was due to reach Princes Street Station at 9.27 pm. When the train came in, the 300 or so persons on the platform were disappointed to find that no Barra men were on the train . . . the men had got into the wrong portion of the train at Larbert and had been carried to the Waverley Station. Mr Donald Shaw, their law agent, and several members of the committee formed to look after the interests of the Barra men immediately repaired to the Waverley Station to welcome the squatters. Few persons were in the station, but a cheer was raised as the blueclad fishermen made for their quarters in High Street.

It is remarkable that the sight of ten fishermen in the station was so unusual that ordinary members of the public realised who they were, and it shows that there was a lot of press coverage in advance of the trial.

At the trial the next day,

the proceedings excited a considerable amount of public interest. The courtroom was packed to overflowing, while a large number of spectators overlooked the scene from the galleries above. The squatters were accommodated in a seat immediately behind the reporting bench. A bronzed and hardy lot they looked in their seafaring garb, the respectability of which certainly did not suggest dire poverty.

Counsel for Lady Cathcart put the case for the complainer. He stated that the men had breached the interdict served on them by the court, had continued to occupy the land, and intended to continue to do so. The only previous case where a respondent for breach of interdict had taken up that position was in 1887, and this led to his imprisonment.

Counsel for the men, Arthur Dewar, stated that ‘they admitted that they had gone to Vatersay without the authority of the complainer, and that they had failed to obey the order of the court.’ He wished to dispel the impression given in some quarters and in the press, that ‘the respondents were reckless and unprincipled men who had wantonly seized the property of a benevolent landlord, notwithstanding all the benefits they had received throughout their lives.’ As evidence of the true situation he quoted from the report by Sheriff Wilson, who had failed in an attempt to persuade the raiders to leave Vatersay the previous year. In conclusion, he said,

They had been driven by the system and circumstances they were powerless to control into disobedience. The disobedience was not due to disrespect, but entirely to their environment. The respondents had asked him to express the hope that those who could reform the law should take note of what they had had to suffer, and so alter the law that they might have the opportunity of becoming once more law-abiding citizens. There was an outburst of applause at the conclusion of the speech. The ushers immediately called for silence, and the Lord Justice Clerk characterised the applause as ‘most unseemly.’

The Lord Justice Clerk, having established from Mr Dewar that the men intended to continue to defy the court by remaining in Vatersay, delivered judgement. He said that the background to the case was

not material for the court at all . . . In view of all that had been said about not dealing harshly with such ignorant men, the sentence to be pronounced on them would be a limited one. It was right to give warning that if the breach was continued after the expiry of the sentence the case could not be dealt with as it was being dealt with now. The sentence pronounced was two months imprisonment upon each of the respondents. The crofters, who had the terms of the sentence interpreted to them in Gaelic by their solicitor, accepted the situation stolidly. After the sentence was pronounced they retired to one of the side rooms in Parliament House and partook of refreshments. The intention was to have them removed to the Calton Prison in the ordinary prison van, but Mr Donald Shaw, their agent, objected, and offered to provide another conveyance. Shortly after three o’clock they were removed in cabs. Three prisoners and a policeman were in each cab. As each batch emerged into the square a cheer was raised, and they were exhorted to keep up their courage by persons in the crowd. They all appeared to be in good spirits, and smilingly acknowledged the greetings of the crowd.

How did this ‘extraordinary proceeding’, as a newspaper writer put it, come about? This book sets out to tell the story of the background to these events, starting with the earliest human occupation of Vatersay, and bringing the account up to date with the more recent history.

1. Early times

Vatersay, ‘Bhatarsaigh’ in Gaelic, lies at the southern end of the Outer Hebrides or Western Isles. It is the first, and the largest, of a chain of five small islands to the south of Barra. It is only 200 metres from Barra at the narrowest point of the Sound of Vatersay, and Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay and Berneray are strung out to the south-west. These islands, together with Barra and some islands off its north-east coast, are known as the Barra Isles. They make up the parish of Barra, which was described in 1847 as ‘composed of a cluster of islands surrounded by a boisterous sea, making the passage from one island to another a matter of very considerable hazard.’ Since 1912 Vatersay has been the most southerly inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides, for people from the islands to the south raided and settled there between 1907 and 1912, leaving their more distant islands deserted.

Vatersay measures about five kilometres (three miles) east–west by a slightly shorter distance north–south. It is highly irregular in shape, consisting of northern and southern hilly parts, joined by a low sandy isthmus only about 400 metres wide at its narrowest point, flanked on either side by magnificent beaches of white shell sand. These beaches are the most notable physical feature of the island according to today’s tastes, but in the past the eastern bay, Bàgh Bhatarsaigh, is the feature most often mentioned by early writers, being one of the best natural harbours in the Outer Hebrides. From the sea, Vatersay looks like two islands, which, some thousands of years ago, it was.

The geologist John MacCulloch described Vatersay in 1816 thus: ‘This island consists of two green hills, united by a low sandy bar where the opposite seas nearly meet. Indeed if the sea did not perpetually supply fresh sand to replace what the wind carries off, it would very soon form two islands; nor would the tenant have much cause for surprise if, on getting up some morning, he required a boat to milk his cows. The whole island is in a state of perpetual revolution, from the alternate accumulation and dispersion of sand-hills; which at least affords the pleasure of variety.’

The isthmus, Meallaich in Gaelic, is technically a tombolo, or sand bar joining two islands. In MacCulloch’s day it seems to have been bare sand, but in time vegetation began to colonise it and it became machair, the rich grassland of the west coasts (mainly) of the Outer Hebrides, which supports a profusion of wild flowers in summer. The machair extends south to the southern beach, Bàgh a’ Deas, and eighteenth-century maps show that this area was also sandy at that time. From 1850 it was the arable land of Vatersay Farm, and since 1909 it has been the croft lands of Vatersay Township. There are two other areas of machair: east of Caraigrigh on the Uidh peninsula, and at Caolas, between Traigh Bhàrlais and Port a’ Bhàta. Many of the early accounts of Vatersay mention its fertility.

Recent research has shown that the tombolo began to develop about 7,000 years ago, when sea level was several metres lower, and it may not have become a permanent fixture, above high-tide level, for some time. During its history there have been periods of growth, stability and erosion. In its present form, therefore, Vatersay is a very young island. In contrast to the isthmus, the rest of the island is composed of rounded hills of Lewisian Gneiss, the rock of all the Outer Hebrides, which at nearly three thousand million years old is amongst the oldest rock on earth. The hills, rising to 190 metres (625 feet) are partly covered with rough grassland and heath, some of it peaty, but there is a good deal of bare rock. In places there is glacial till, a legacy of the ice sheet which covered the islands during the last ice age. There are no trees, and no large streams. There are a few very tiny lochs, so small that they hardly merit the term. A writer in 1845 described sea-caves on the west side of the island which had been used for storing smuggled goods.1

Topographically, Vatersay has more in common with Sandray than with the three other islands to the south. Unlike these three, they have no sea cliffs of any height. Many areas of the coastline are low-lying and were settled, in contrast to the others where settlement sites were more limited. Sandray is under a kilometre (half a mile) south of Vatersay. It is roughly circular, and up to about three kilometres (two miles) across. The interior rises to two peaks, the highest being Càrn Ghaltair, 207 metres (678 feet) high. In historical terms, too, Vatersay and Sandray were closely linked. After Sandray’s crofting population was evicted in 1835 it was used as grazing by Vatersay Farm, and since 1909, when both islands were bought by the state, it has continued to serve that function for the crofters of the southern townships of Vatersay. Vatersay and Sandray were more closely connected culturally, as well as physically, to Barra.

The claim made in 1906 that ‘Vatersay may yet become a place famous in history’ turned out to be prophetic: it gained national attention over the raiding and settlement by people from neighbouring islands later in 1906 and the following years. It became, in another writer’s words, ‘the theatre upon which was fought one of the keenest conflicts in the struggle for land reform in the Hebrides.’ This period is documented in detail in the form of records and newspaper reports. Vatersay had previously been in the news in 1853, when the Annie Jane was wrecked and about 400 emigrants were drowned. Otherwise, before the twentieth century, the outside world took little interest in the island and its history is not well documented. There are very few visitors’ accounts; it did not have the spectacular cliff scenery and birdlife or the remoteness of Mingulay, for instance. While it is mentioned in many books and articles, there are very few articles devoted to the island. From the scanty evidence, we can piece together something of Vatersay’s history from 1549, when it is first mentioned, until the raids began in 1900, and then the story of the raiders can be told in much more detail. For the earlier history and prehistory we rely on archaeology and on what is known about the Barra Isles as a whole.

The Barra Isles, and the Outer Hebrides generally, may have been first colonised by small groups of hunter gatherers about 6000 bc, but the earliest definite evidence of occupation in Barra dates to about 3600 bc. This is the site of a Neolithic dwelling, whose inhabitants practised agriculture, at Allt Easdal on the south coast opposite Vatersay. The islands were rather different at that time: sea levels were several metres lower so there was a greater land area, and, in contrast to today’s bleak and treeless landscape, they were wooded. Vatersay would have been inhabited then, too; the sound separating it from Barra would have been narrower, and in any case the sea was a highway rather than the barrier it became in more recent times. Vatersay was probably still two islands at that time, as the isthmus may not have become a permanent feature.

Finding evidence of the early settlers is difficult: rising sea levels since the end of the last ice age about 10,000 years ago (which separated Vatersay from Barra by the flooding of what became the Sound of Vatersay) have drowned the coastlines where people are likely to have been living. In some places inland sites and landscapes have been buried under peat or wind-blown sand. The archaeology of the Barra Isles was investigated systematically for the first time during the 1990s by archaeologists from Sheffield University. They found a large number of buildings, monuments and other structures of all periods and of many periods, in other words, sites where building stones have been reused over time. Certain types of prehistoric monuments are found only in the Barra Isles, and in some cases only on some of the islands. It is often difficult to identify what appear to be grass-covered piles or settings of stones with certainty, since such sites could be anything from 5,500 to 100 years old.

Several sites on Vatersay date to the later Neolithic period, between about 3000 and 2000 bc. One is a passage grave, a variety of chambered tomb, on the eastern slopes of Beinn Orosaigh, Caolas. Only the stones of the passage and burial chamber remain, the cairn which once covered it having been removed. Neolithic pottery was found eroding out of a midden (or rubbish dump) on the eastern side of the islet of Bioruaslum, off the west coast of Vatersay, a site presumably occupied for its defensive nature. Also on the islet is a stone-built structure resembling a chambered tomb. Pottery, possibly of Neolithic date, was found in a midden on the south side of Traigh Bhàrlais, Caolas.

There are various ‘ritual’ or funerary monuments of the late Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, roughly 3000–1500 bc. An arc of stones may be part of a possible stone circle on the western slopes of Am Meall overlooking Eorasdail. There are three possible standing stones, only one of which is still standing: this is a 1.8-metre high stone, forming one side of the entrance of a more recent enclosure on the eastern slopes of Beinn Ruilibreac, so it is possible that it is not of great antiquity. An apparently fallen stone lies in a gap between sections of a massive earth bank, of unknown date, which runs north–south across South Vatersay east of the summit of Beinn Cuidhir. The third possible fallen standing stone is fifteen metres from the shore at Beannachan.

During the period 2000–1000 bc, in the Bronze Age, each island appears to have had variations of types of burial cairns. Vatersay has by far the largest number – twenty nine – of ‘kerbed cairns’ in the Barra Isles. These cairns are mounds of stones enclosed by a ring of large stones lying horizontally, forming a kerb to the cairn. They are found in groups or cemeteries, one particularly striking group of nine being located in the formerly cultivated area on the north side of Bàgh Siar, west of Treasabhaig. These cairns, with some others nearby, are the only such cairns in North Vatersay. Two cairns in South Vatersay were excavated by Sheffied University archaeologists, one on the west side of the hill crowned by Dun Bhatarsaigh, and one further west. The cairns had been built in a complex way, and contained cremated human bone and peat ash, brought from cremation pyres somewhere else. In one, the eastern cairn, an unfinished stone ard (plough), an unfinished stone axe head, a stone rubber for grinding grain on a quern, and half a bronze cloak fastener were found. It also contained a long stone slab which may previously have been a standing stone, and this has been erected in the middle of the restored cairn.

Only a few sites of dwelling houses of the Bronze Age population have been identified, but several habitation sites dating to the Iron Age, roughly 500 bc to ad 500, are known. Round houses and wheelhouses were the dwellings of the majority of the population. They had low walls of stone, with, presumably, thatched conical roofs. About twenty have been identified, all but two on North Vatersay. Wheelhouses have lengths of walling radiating out from the hearth in the open area at the centre, like the spokes of a wheel. Four, all on North Vatersay, have been identified. The chapel of Cille Bhrianain on Uinessan may have been built on the site of an Iron Age house, as pottery of that period has been found on the mound on which it is built. Although it is impossible to know how many of these houses were inhabited at any one time, Vatersay seems to have been well-populated during this period.

There are two brochs or duns, round towers which had double walls separated by galleries and staircases. Both are on hill tops. Dun a’ Chaolais is above the road as it crosses the neck of the peninsula south of Caolas. The lower courses of the walls of the tower can be seen amidst the rubble of the collapsed higher courses. Dun Bhatarsaigh, on the hilltop west of the township of Vatersay, is even more ruined, its stones having been taken away to be used somewhere else, perhaps in the building of Vatersay House in the eighteenth century. The two brochs may represent the strongholds of the dominant families in North and South Vatersay respectively; the two parts of the islands may still have been separate, or partially separate at that time. Several other small islands in the Barra group, including Sandray, have one broch or dun each, and Barra has several. There appears to be an abandoned broch construction site about 250 metres west of Dun a’ Chaolais: part of the wall base of a massive round building was begun but never finished, perhaps because the decision was taken to build Dun a’ Chaolais instead. On the south side of North Vatersay, about 200 metres west of the kerbed cairns, is a large mound of huge blocks of stone, grassed over, possibly a much-ruined broch or dun.

Another type of defensive site is on the island of Bioruaslum, off the north-west coast. An arc of walling runs for about 100 metres across the eastern part of the island, the remainder of that part being defended by low sea cliffs and the narrow channel which separates it from the main island. The unusual feature of this site is that the defended area is well below the defensive wall, and any attackers would look down on it from the steep hillside. The closest parallels for this site are in Ireland, where they date to the early to middle centuries of the first millennium ad. On a terrace on the south side of the island, outside the defended area, is a group of circular huts of unknown date.

Other sites in Vatersay may be prehistoric. There are a number of boat-shaped stone settings in the Barra Isles of a type which in other islands – Lewis, Colonsay, the Orkney group – have turned out to be Norse burial monuments. Vatersay has about twenty of these, half the total in the islands, and one of them, at Eorasdail, was excavated by the Sheffield archaeologists. Disappointingly, no evidence whatever of their date or function was found; all that could be said was that they were earlier than land boundaries, marked by lines of stones, of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. If there had been human bone in them it would not have survived in the acidic soil; but many are a long way inland and up hillsides, and the conclusion was that they were probably not Norse. Other undated occupation levels can be seen in eroding sections of the sandy areas of the island. These are middens and sometimes remains of stone walls. In some cases there are alternating layers of midden and sand, indicating different periods of occupation separated by periods of sand accumulation. There are also ancient soil levels in some sections, indicating periods of stability. Beneath the upper levels of sand of the isthmus, an ancient soil can be seen which had developed on earlier sand dunes, but the dates of these features are unknown. Enclosure walls are being eroded by the sea at Port a’ Bhàta, Caolas, and these presumably date from a period when sea level was lower.

Sandray has many prehistoric sites. There are two possible chambered tombs, possible standing stones, and Bronze Age cairns classified as ‘bordered’ rather than kerbed, where many of the stones enclosing the cairn are upright rather than horizontal. There are several Iron Age round house sites, and a broch or dun high up on the western slopes of Càrn Ghaltair. Archaeologists from Sheffield University excavated part of a mound at Sheader created by the accumulation of successive phases of buildings and occupation debris over 3,500 years. The earliest level is a shell midden dating to about 1500 bc, the Bronze Age, and there were walls and post holes of a later, Iron Age, building. The site was abandoned for a while and reoccupied in medieval times, followed by two phases of eighteenth- to nineteenth-century occupation. Finally, there are the houses of the Sandray raiders built during their sojourn there between 1907 and 1911. A very interesting area of Sandray is inland from the beach at the south-east end, where sand has been shifting for thousands of years. It is known as the ‘wineglass’ on account of its appearance from the sea. Wind erosion of dunes shows occupation levels between periods of sand accumulation, and shifting sand seems to be revealing old land surfaces with stone-built structures and occupation debris – shells, animal bones, pottery and worked stone – on them. The stones and artefacts on the bottom of the main ‘blow-out’, which is about twenty metres deep, probably originated from higher levels and have worked their way down as the sand under them has been blown away. Dating has shown that these occupation levels are Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Western Scotland was settled by Gaelic speaking ‘Scotti’ – hence Scotland – from northern Ireland during the first several centuries ad. Their language and culture gradually took over from the native Pictish culture. Nearby Pabbay has one of only two so-called Pictish symbol stones in the Outer Hebrides. These are memorial stones bearing symbols of a design common to this type of monument, and probably date from between the fifth and seventh centuries. Traditionally, the Hebrides were Christianised by St Columba and his followers after his arrival in Iona from Ireland in 563. The Celtic type of Christianity was based on the monastic ideal, and there is evidence for Christians, probably hermits, living in Barra and Pabbay in the following centuries: there are at least three gravestones bearing incised crosses in Pabbay, and an early cross was added to the symbol stone.

The name Pabbay is derived from the Old Norse for Hermits’ or Priests’ Isle, indicating the inhabitants at the time of the Norse (Viking) raiding and settlement of the Hebrides which began about 795. An Irish monk, Dicuil, said of the Hebrides in about 825, ‘Some of these islands are small; nearly all alike are separated by narrow channels, and in them for nearly a hundred years hermits have dwelt, sailing from our Scotia. Now, because of these robbers the Northmen, they are empty of anchorites.’ It is possible that there were hermitages on Vatersay and other islands south of Barra, too; they all had chapels in later times, which may have had early origins or been built on the sites of earlier buildings.

Being on the sea route from Norway to Ireland and the Isle of Man, the Hebrides were used as bases for raids further south. According to one of the Norse sagas, Onund Wooden-leg was the first Viking to come to Barra, in 871. He arrived with five ships, drove out a local ruler, Kjarval, and plundered in Scotland and Ireland. ‘They went on warfare in the summers, but were in the Barra Isles in the winters.’ Graves of these early settlers have been found on Barra, dating from the ninth century, before the Norse adopted Christianity.

In time the Norse raiders became settlers, and the Hebrides became part of the Norse Kingdom of the Isles. The settlement was on such a scale that their language became the predominant one, at least for place-names. The extent of Norse settlement in the Barra Isles is uncertain; it was less dense than in Lewis, and there are relatively few names which indicate actual settlements of Norse speakers. There is Borve in Barra, Sheader in Sandray, and Suinsibost in Mingulay. There is a tradition that a bishop stayed in a house at Treasabhaig in Viking times.2

Many of the place-names have Norse elements which survived after Gaelic reasserted itself following the loss of Norse political control in the thirteenth century, and the actual meanings of the names was forgotten. The -ay or -a endings of the names of the islands are Norse, being derived from the word for island, and some of the other elements in the names are also Norse. In some names, the elements have changed so much over time that their origins and meanings are uncertain. The name Vatersay itself is one of these. There are various possible derivations of the first element, all of them Old Norse. One is from veôr, ‘weather side’, referring to the coastline exposed to the westerly winds. Another is from vaôill, ‘ford’, referring to the isthmus as a place which boats could be dragged across from one bay to the other. Then there is vatn, ‘water’, which would refer to sea-water and the long coastline. Sandray, Sanndraigh in Gaelic, derives from the Old Norse for ‘island of the sands’.

The place-names are descriptive or refer to the use to which places were put, or to events or to people. Uidh derives from Old Norse eiô, ‘isthmus’. Theisheabhal Mòr, the name of a hill, derives from the Old Norse words hestr, ‘horse’, and fjall, ‘mountain’; mòr is Gaelic for ‘big’. Some names have both Norse and Gaelic elements. Others are wholly Gaelic and in many cases more recent. Allt a’ Mhuilinn, for instance, means ‘stream of the mill’, indicating that it once powered a water mill; it is one of the streams draining into the north side of Bàgh Siar (West Bay). On the other side of the bay is an inlet of the sea called Sloc Mhartainn. Sloc is Gaelic for ‘gully’, Mhartainn is Martin. The tradition is that Martin was an Irish itinerant trader who was staying at Vatersay House when his host’s brother offered to take him to a ceilidh, but he killed Martin instead and threw him in the gully.3

The Norse Kingdom of the Isles reverted to the Scottish crown in 1266 and was thereafter ruled by the Lords of the Isles. The Scottish clans originated in the period between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, as groups of people who claimed kinship with, and owed allegiance to, a hereditary chief. The clan occupied a particular territory within which all property was held by the chief on behalf of the clan; the clan members paid rent for land in kind and in military service. By 1427, the MacNeils had emerged as the chiefs of Barra, for in that year they were granted the Barra Isles by the Lords of the Isles. However, they had probably been the chiefs for some time; they claimed descent from ‘Neil of the Nine Hostages’, king of Ireland in the fourth century AD.