7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Collins Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

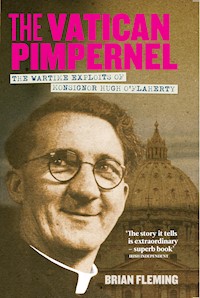

During the German occupation of Rome from 1942 to 1944, Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty ran an escape organisation for Allied POWs and civilians, including Jews. Safe within the Vatican state, he regularly ventured out in disguise to continue his mission, which earned him the nickname 'the Pimpernel of the Vatican'. Kappler, the Gestapo chief in Rome, ordered him captured or killed. When the Allies entered Rome, Monsignor O'Flaherty and his colleagues had saved over 6,500 lives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

BRIAN FLEMING

The Collins Press

Cast of Characters

The Rome Escape Organisation

Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, the founder of the organisation.

John May, a member of the Council of Three.

Count Sarsfield Salazar, a member of the Council of Three.

Major Sam Derry, the senior British officer involved in the organisation from late November 1943.

The Helpers

The Irish: Delia Murphy, Blon Kiernan, Frs Buckley, Claffey, Treacy, Lenan, Madden, Roche, Tuomey, Forsythe and Brother Humilis.

The Maltese: Mrs Henrietta Chevalier, Brother Pace, Frs Galea, Borg and Gatt.

The British: Lts Simpson and Furman, Molly Stanley, Hugh Montgomery, Flt. Lt. Garrad-Cole and Major D’Arcy Mander.

The New Zealanders: Frs Sneddon and Flanagan.

The Czechoslovak: Private Joe Pollak.

The American: Monsignor Joseph McGeogh.

The Yugoslavs: Milko Scofic and Lt. Ristic Cedomir.

The Dutch: Fr Anselmo Musters.

The French: Jean de Blesson and François de Vial.

The Greeks: Evangelo Averoff and Theodoro Meletiou.

The Russian: Fr Borotheo Bezchctnoff.

The Italians: Renzo and Adrienne Lucidi, Princess Nini Pallavicini, Fr Giuseppe Clozner, Secundo Constantini, Giuseppe Gonzi, Sandro Cottich, Mimo Trapani, Fernando Giustini, Giovanni Cecarelli, the Pestalozza family, Prince Filippo Doria Pamphilj, Iride and Maria Imperoli, Prince Caracciolo and scores of others whose courageous support for the work of the organisation was crucial.

The Diplomats

Dr Thomas Kiernan, Irish Minister to the Holy See.

Michael MacWhite, Irish Minister to Italy.

Sir D’Arcy Osborne, British Minister to the Holy See.

Harold H. Tittmann, United States Chargé d’Affaires to the Holy See.

Ernst von Weizsaecker, German Ambassador to the Holy See.

The Vatican

Pope Pius XII, (Eugenio Pacelli, a native of Rome).

Cardinal Luigi Maglione, Secretary of State.

Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, Under Secretary for Ordinary Affairs (subsequently Pope Paul VI).

Monsignor Domenico Tardini, Under Secretary for Extraordinary Affairs.

The Allies

General Harold Alexander, Supreme Allied Commander.

Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, senior American officer.

The Nazis/Fascists

Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Kappler, Head of the Gestapo in Rome.

Pietro Caruso, Fascist Chief of Police.

Pietro Koch, Chief of the Fascist Political Police Squad.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Supreme German Army Commander in Italy.

The Observers

Mother Mary St Luke, an American nun living in Rome who published her diaries under the pseudonym, Jane Scrivener. Excerpts from her diary are referenced and dated in the text, for the convenience of the reader, as well as in the more conventional manner.

Michael MacWhite, an Irish diplomat living in Rome. Excerpts from his archive – including letters to the Department of Foreign Affairs, coded cablegrams and diary entries – are referenced and dated in the text, for the convenience of the reader, as well as in the more conventional manner.

Introduction

On Monday 10 June 1940, the dictator Benito Mussolini announced to the Italian people that their country would enter the War on the following day as partners of Germany. Until then, the career of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, a Kerryman working in the Vatican, had been relatively routine. Following ordination in 1925, he fulfilled various roles in the Church, before being appointed to a position at the Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office in 1936. However, his speedy rise through the ranks of the Vatican civil service is a clear indication that he was a man of some considerable ability. The events of the War years illustrate that, as well as being an able man, O’Flaherty possessed truly great qualities of leadership, ingenuity, compassion and courage, both physical and moral.

Early on in the War, O’Flaherty was merely an observer. As he remarked to a friend later, ‘When this War started I used to listen to broadcasts from both sides. All propaganda, of course, and both making the same terrible charges against the other. I frankly didn’t know which side to believe – until they started rounding up the Jews in Rome. They treated them like beasts, making old men and respectable women get down on their knees and scrub the roads. You know the sort of thing that happened after that; it got worse and worse, and I knew then which side I had to believe.’

As he was well known in the city, many of those being hounded by the authorities began to seek his help. With assistance from many of his colleagues in religious life and local civilians, he began to hide and care for those on the run. Prominent among his most active helpers were a number of Irish people. The Italians surrendered in the summer of 1943 and many Allied prisoners escaped as their warders left their posts. The numbers seeking help began to increase and by that autumn he had placed over a thousand people in safety in Rome and the surrounding areas. Some British officers, who were escapees themselves, moved in to help him and his friends at that stage.

The Nazis became aware of his activities and actively set about trying to capture him with the result that a deadly game of hide-and-seek began. If captured, he would certainly have been tortured and killed. However, he continued his work, often walking the streets of Rome in various disguises. It was for this sort of activity that he earned the nickname ‘The Pimpernel of the Vatican’.

By the time of the Liberation of Rome in the summer of 1944, he and those whom he inspired had ensured the safety of more than 6,500 people, including 2,000 or so civilians.

For his outstanding contribution to the welfare of his fellow man, O’Flaherty was honoured by many governments, including the British (a CBE) and the Americans (a Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm). Yet, strangely, this truly remarkable man’s story is not well known in his native Ireland. Sadly, no civil authority at any level has commemorated his extraordinary achievements. I hope that by writing this account the position will be rectified somewhat.

Brian Fleming

1 Rome 1941

The First World War was a bitter episode for the Italian people. Indeed the experiences which the Italians had during that war and its immediate aftermath explain, more or less completely, the course of Italian history for the next 25 years. From the time they joined the war until its end, the Italian armies were in battle on the Austrian front displaying great heroism without gaining a hugely significant amount of ground. However, tragically, they lost 600,000 of their men in a three-year period. Despite the fact that they were on the victorious side, Italy gained very little from the outcome of the war. France and Britain divided the main spoils between them and Italy’s only significant gain was a small piece of what had formerly been Austria. In addition, in 1921 when the US and Britain agreed to fix treaty limits on the size of the fleet which the various Allied powers were to operate, Italy was forced to accept limitations which resulted in an entitlement to the same naval strength in the Mediterranean as the British Royal Navy. Clearly this was a direct insult to Italian national pride.

Throughout this period Italy was fairly unsettled. There was a clear disparity between what Italians felt they were entitled to after the war as members of the victorious Allied side, most particularly in light of the huge level of human sacrifice involved for them, and what had been assigned to them. Veterans and their families and others, mainly in the working and lower middle classes, were deeply dissatisfied with this situation. In addition, it was a time of recession and unemployment and the rise of extreme nationalism. Strikes and rumours of revolution were the order of the day. These unsettled conditions proved to be an ideal breeding ground for the rise of Fascism. In 1922 the King, Victor Emmanuel III, invited Benito Mussolini, leader of the Fascist group, to form a government. Within four years, Mussolini had effectively become a dictator, outlawing all other political parties, undermining civil liberties and imposing a totalitarian regime. At the same time, he managed to gain popularity by propaganda, public works projects, and, most particularly, by creating the appearance of order.

In 1929 the Lateran Treaty was concluded between Mussolini’s Government and the Papacy. In the eyes of the Italian people this gave Mussolini further status. Under the terms of the Lateran Treaty, that part of Rome which comprises the Vatican and St Peter’s became an independent sovereign state governed by the Pope. In addition, the Treaty allowed for papal governance of extra-territorial properties belonging to the Catholic Church in various parts of the city, including the Basilicas of St John Lateran, St Paul and St Maria Maggiore, together with all the buildings connected with them. Other properties included the offices of the Propagation of the Faith and of the Holy Office near St Peter’s and the papal residence at Castelgandolfo. This essentially gave these buildings the same status as a foreign embassy has nowadays. The entire extent of the Vatican City itself is 108 acres and it is wholly contained in Rome, making it the smallest state in the world. The usual population based in the Vatican is approximately 500. Besides Pope Pius XII, the other senior officials in the Vatican when the Second World War started were Cardinal Maglione, Secretary of State, and his two assistants, Monsignor Montini, Under Secretary for Ordinary Affairs (essentially internal Vatican/ Church matters) and Monsignor Tardini, Under Secretary for Extraordinary Affairs (essentially external issues). Monsignor Montini afterwards became Pope Paul VI.

Given the origins of the movement, it is not surprising that the Fascist Government adopted an expansionist foreign policy based on aggression. As early as 1919, at the foundation of the Fascist Movement, Mussolini was articulating the case that Italy needed more territory for her growing population. In 1935–6 the Italian army invaded and conquered Ethiopia and also in 1936 Italy sent troops to support Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Later that year Mussolini and Hitler established the Rome–Berlin Axis. In 1939 Italy took over Albania, and the two dictators, Hitler and Mussolini, concluded a military alliance known as the Pact of Steel. This agreement was signed on 22 May causing great concern to those within the Vatican who viewed any close relationship between Italy and Hitler as dangerous.

The war between Britain and France on the one hand, and Germany on the other, began on 3 September 1939. Serious efforts which were already under way in the US and Great Britain to keep Italy out of any war were immediately accelerated. The then American President, Roosevelt, was already acquainted with the Pope. Pope Pius XII, when he was a Cardinal, had visited the US in November 1936. At that stage there were no formal diplomatic links between the US and the Holy See, but Roosevelt sent the Ambassador in London, Joseph Kennedy, as a Special Envoy of the President to the Coronation Ceremony when the then Cardinal Pacelli became Pope in March 1939. This was the first time an American President had been represented at such an occasion. (As it happens, a future American President was there also, as John Fitzgerald Kennedy attended with his father.) President Roosevelt had concluded that, in the event of war, establishing some sort of working relationship with the Holy See might prove useful. The Vatican at that time had representatives in a total of 72 countries throughout the world from which it could gather significant information. In addition, 38 countries had official representation at the Holy See. The President decided to go ahead with establishing this link but it left him with a political problem. If he decided to send an official representative in the normal way, it would require a vote in the Houses of Congress to provide the necessary funds. It was doubtful that he would be successful in this because there was a strong feeling then current in the US of the need to separate church and state. In public relations terms, while the decision of the President would be popular with Catholic voters, it would alienate Protestants. As a way around this problem he decided to send a personal representative of himself as distinct from an envoy of the US Government. To obviate the need for funding, which could be provided only by a favourable vote in Congress, he needed to find a man who would require no payment. The President identified Myron Taylor as just such a man. At that stage, Taylor was President of the United States Steel Corporation. He was an Episcopalian and had a keen interest in the role of churches and churchmen in contributing to the moral order. He also had a knowledge of, and interest in, Italy and already owned property near Florence.

In his Christmas 1939 message to the Pope, the President announced the appointment of Taylor. It resulted in some criticism domestically but not of a hugely significant nature. Officially Taylor’s appointment was to address refugee issues which were expected to arise particularly from the situation of Jews living in Germany and German-occupied territory. He had previously served on the President’s Inter-Governmental Committee on Political Refugees in 1938 and so had a track record in that regard. As he agreed to serve without a salary, and his expenses were paid from funds allocated to the Committee on Refugees, the President did not need the approval of the Houses of Congress for his appointment.

Taylor arrived in Rome in early 1940 and immediately linked up with the British Minister to the Holy See, D’Arcy Osborne, and the French Ambassador, Charles-Roux. The US State Department was directed by the President to supply logistical support to Taylor and this took the form of Harold Tittmann who was then Consul General in Geneva. The diplomats, working with the Pope and the Vatican authorities, engaged in extensive efforts over the next few months to keep Italy out of the War. For example, Taylor had seven different appointments with the Pope in the period from 27 May to 23 June which was an unprecedented number of meetings over such a short period for a foreign diplomat. The general view was that President Roosevelt was far more likely to have an influence on Mussolini than anyone else. Indeed, even as early as the first week of 1940, the President was proposing to the Italian Government a common approach by Mussolini, the Pope and himself to restore peace in Europe. Furthermore, he indicated the desire for a conference with the Italian leader some time during the course of the year. Subsequently he sent the Under Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, on a visit to Rome during which he met Mussolini and emphasised again the President’s anxiety that Italy would enter the War. In the meantime, the British Government was making clear to the Italian authorities that they had friendly relations with many governments, some of which were governed in a similar manner to Italy and that they would draw clear distinctions between the Nazis of Hitler and the Fascists of Mussolini. On 19 April Taylor telegraphed Roosevelt advising that he had conferred with the Cardinal Secretary of State in the Vatican, Maglione, and the representatives of various European countries at the Holy See, and all were agreed that the situation in relation to Italian neutrality was now approaching a critical juncture. They recommended that the President and the Pope engage in parallel appeals to Mussolini to keep out of the War. This suggestion, after some delay, was put into effect.

During all this time the Italian Foreign Minister was Count Ciano. He was Mussolini’s son-in-law, being married to the Dictator’s favourite daughter, Edda. Ciano had signed the Axis agreement with Germany on behalf of Italy but soon began to doubt the value of the link. He was one of those active in trying to persuade Mussolini not to join the War. Under the original Axis Agreement the Italian understanding was that war, if it were to happen, would not commence before 1943. Although he shared the Duce’s expansionist policies, Ciano was acutely aware that Italy was in no position to engage in a prolonged war effort. He was also sensitive to the fact that among the public there was little enthusiasm for such a policy. Unfortunately, his advice, as well as the diplomatic efforts being made by the Vatican and various foreign governments, fell on deaf ears. Allied diplomats and Vatican authorities who were working to keep Italy out of the War did not foresee the quick collapse of France and the British withdrawal from Dunkirk in late May. Mussolini was, most likely, influenced by the fact that France had fallen and he thought at that point that he was joining the winning side. On Monday 10 June he announced to the Italian people that they would be at war the following day as partners of Germany.

The partnership between Germany and Italy was never one of equals. Italy’s economy could only support a fraction of the military expenditure of Germany. The Italian armed forces had been allowed to decline in numbers since the previous war and emigration to the US had increased greatly. Much of the equipment which the Italian armed forces had was seriously outdated.

In relation to Italy’s participation in the War, there was also a question mark as to public opinion. The Italians traditionally had little or no enmity towards the various Allied countries. For a long time, there had been close connections between the Italian and English upper classes and there was a high level of Anglophilia among the various noble families in Rome. The Italian working class had a high regard for the US. Many of their counterparts, including family members, had emigrated to America and they were strongly aware of the negative views of Nazism held in that country.

Italy’s entry into the War immediately raised questions for the diplomats who were living in Rome representing those countries with whom Italy was now at war. The Lateran Treaty had clauses to govern just such a situation but they were somewhat vague. The Vatican Secretary of State, Cardinal Maglione, had raised this issue with the authorities as early as 1938. There were differing opinions held within the Italian Government – between the authorities in Foreign Affairs, the War Office and the Ministry of the Interior – so no clear response was issued. Eventually in May 1940 the Italian Government informed the Holy See that the diplomats from countries who might eventually be at war with Italy would have to leave and take up residence in a neutral country or move into the Vatican. At the invitation of the Pope, D’Arcy Osborne moved into the Vatican, as did the French and Polish Ambassadors among others, the week after Italy declared war. They were located in a pilgrim hostel attached to the Convent of Santa Marta on the south side of St Peter’s Square. As the French had appointed a new Ambassador, d’Ormesson, the British Minister D’Arcy Osborne was now the senior diplomat among this group. In the early days, the facilities in the accommodation were fairly limited and D’Arcy Osborne found himself having to use Monsignor Montini’s apartments for taking a bath. The two men got to know each other and became close friends during the succeeding months and years.

Of course the Italian authorities laid down some conditions. The diplomats representing those countries were now enemies of Italy, and so had to reside within the Vatican and not cross the border into Italy. For exceptional reasons, however, they were allowed to ask for permission to leave the Vatican and go into Rome. If this were granted, they were to be continuously escorted by a police officer. They were not allowed to send any telegrams in code. They were allowed make official communications to their governments but only in respect of their work as envoys to the Holy See. This excluded any reference to matters in relation to Italy. Their families were allowed to go to the seaside during hot weather, visiting the resort at Fregene. The diplomatic cars could leave the Vatican and go straight out to Fregene without going through the city centre and so avoid any embarrassment to the Italian Government.

By contrast the Irish representatives were there on behalf of a neutral country and so did not have to move into the Vatican. The Irish Minister at that time was Dr T. J. Kiernan. Thomas Kiernan was born in 1897 in Dublin and educated at St Mary’s College, Rathmines and University College Dublin. He joined the Civil Service in the offices of the Inspector of Taxes in 1916 and was stationed in Galway from 1922 onwards. There he met his future wife, Delia Murphy. They became engaged a couple of years later. Both sets of parents disapproved of the engagement. It is easy to understand why the parents were concerned that this might not be an ideal match as the two had completely different personalities. Kiernan at that stage had already taken his Master’s and intended doing a Ph. D. with a view possibly to taking up an academic career. Delia Murphy on the other hand had no interest in such a career and was very much into the social life of Galway. She was, even at that young age, a noted singer. Despite the disapproval of their parents, they got married in February 1924 at University Church in Dublin. Sadly, neither set of parents attended. In April 1924 Kiernan took up an appointment in London as Secretary to Commissioner McNeill in the High Commission Office. He completed his Doctorate at London University.

It is fair to say they were an odd couple. A friend at that time, the distinguished civil servant and author León Ó Broin, noted the contrast:

I found him gentlemanly, courteous and desperately discreet. He was a retiring quiet man who smoked incessantly and I would say highly strung. He was very good looking, almost effeminate; and she was handsome, too, but bustling, almost rough. I wondered how they fitted into the Embassy scene abroad.1

Another friend, the actor, Liam Redmond, observes:

Delia was an extrovert, she liked people who had the same openness as herself, and they liked her. Women with social pretensions and prissy men did not care for her. She just thought such people ridiculous and, typically she would seek out someone who was less hidebound by convention with whom she could have a bit of ‘craic’. If possible at all, she would start a sing-song and soon she would have everyone around her singing along in the chorus.2

However their different strengths were to prove useful in the diplomatic service. She was a very well organised and generous hostess whereas her husband was not at all keen on entertaining. As her future son-in-law remarked some years later:

She was well able for the entertaining side of diplomatic life and I could imagine her taking on anything. I could imagine, however, stuffy formal occasions being very trying for her, but then she could get a laugh out of those. She was totally unaware of any social or class distinction.3

As the years passed, Kiernan’s career took a few interesting turns. The move to London had meant a transfer from Finance to Foreign Affairs and then in the mid 1930s he was transferred again to the Department of Post and Telegraphs on taking up an appointment as Director of Programmes at Radio Éireann. In the meantime, his wife was becoming increasingly well known as a singer and she had begun to record songs which were released by HMV later in that decade. She was encouraged in developing her musical career by Count John McCormack and the famous soprano, Margaret Burke Sheridan, and undoubtedly her husband’s role as Director of Programmes was of assistance. Kiernan was a man of great integrity so it is unlikely that he ever asked anyone to play her music. At the same time, the fact that he was Director is likely to have influenced the selection of music in Radio Éireann. At one of the concerts she gave during those years we see an early example of her courage. She was singing at a concert in the Ulster Hall, Belfast, in April 1941 when the German bombers arrived. The Irish News reports:

The raid revealed many heroes and heroines among quite ordinary people in the city. The bravery of Delia Murphy, wife of Dr Kiernan, Director of Radio Éireann, Dublin, during the height of the blitz, has been the subject of much discussion in Belfast. She was singing at a céilidhe in a large city hall. As bombs rained down, many of the women present became fearful of the consequences. Miss Murphy, however, remained perfectly cool, and kept singing continuously, asking those present to join her.4

Shortly after that, there was another significant change in her husband’s career when he was appointed as a member of the Diplomatic Service in October 1941 to what was seen to be a very important post: Minister Plenipotentiary to the Holy See.

The Irish Government policy throughout the War was to remain neutral. Throughout this period the Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Éamon de Valera, also occupied the position of Minister for External Affairs (now Foreign Affairs). His chief adviser was Joseph Walshe, Secretary of the Department of External Affairs. In the early stages of the War, Walshe was of the view that Germany would almost certainly win:

Britain’s defeat has been placed beyond all doubt. France has capitulated. The entire coastline of Europe from the Arctic to the Pyrenees is in the hands of the strongest power in the world which can call upon the industrial resources of all Europe and Asia in an unbroken geographical continuity as far as the Pacific Ocean. Neither time nor gold can beat Germany.5

(July 1940)

So, while at an unofficial level Walshe was willing to co-operate with the British, he saw it as prudent from the Irish point of view to stay neutral. This view coincided with the Taoiseach’s. Aside from any political considerations, the country was in no position to engage in any serious level of conflict. The army had 7,600 members and suffered from a serious shortage of equipment. The Navy had two vessels and three motor torpedo boats. The Air Corps was similarly equipped. At the beginning and during the early years of the War, Walshe maintained his pessimistic view of the situation.

However, as the War progressed, there is no doubt that assistance was given to the Allied side at an informal level, including the sharing of intelligence and the granting of permission for Allied aircraft to fly over Irish territory in north Donegal to give them more direct access to the Atlantic. As time went by, the Irish authorities distinguished between operational and non-operational flights. By implementing this policy they ensured that most British and American planes which landed on Irish soil were allowed to leave as these were interpreted as being non-operational flights. By contrast, it was highly unlikely that any German plane would make a flight across Irish soil that would qualify as non-operational. These policies, however, were governed by strict censorship arrangements which were then in operation in the country and so were not generally known. As regards activities abroad, the Government was very anxious that the policy of strict neutrality would be observed. Instructions were sent out to staff working in the diplomatic service to ensure that this policy of neutrality was implemented.

The Taoiseach wishes to remind all our staffs abroad, and this also applies to wives, that imprudent and un-neutral expressions of views reach places for which they are not intended and might have serious repercussions on the results of the policy of neutrality which the Government has pursued as the only means of preserving the independence of the nation and the lives of the people … The Taoiseach requires from all the strictest adherence to the foregoing instruction.6

(14 June 1941)

By then, the Government had secured an undertaking from the German Minister that his country’s intention was not to violate Ireland’s neutrality and above all not to invade Ireland. Minister Kiernan was careful to implement the Taoiseach’s instruction to the letter. For example, in one of his reports back to the authorities in Dublin (27 March 1943), he comments:

I have met, socially, the Diplomats of the Axis and Allied Countries in about equal measure and have been careful to avoid giving any impression of stressing social acquaintance in any direction.7

The other senior Irish diplomat in Rome was Michael MacWhite, who was Minister at the Irish Embassy to the Italian Government. Michael MacWhite was born at Reenogreena near Glandore in West Cork on 8 May 1883. His father died in 1900 when Michael was seventeen. At that stage he came to Dublin to sit an examination for the British Civil Service and, during his visit to the city, met Arthur Griffith. They became lifelong friends. MacWhite was successful in the examination and moved to London to take up a position. At the age of eighteen he was Secretary of the Irish National Club in London and very well regarded in Irish circles there. He left London in the early years of the last century and did some travelling. He fought for Bulgaria in the first Balkan War in 1912, then joined the French Foreign Legion in 1913 and subsequently saw action in France, Greece and Turkey. He was wounded at Gallipoli and Macedonia and received the Croix de Guerre three times for his courage in battle. Following the war, he returned to Dublin and contacted his old friend Arthur Griffith with an offer to assist in the setting up of the new State. As a result, he became one of the founders of the Department of Foreign Affairs and saw service in various countries including the US. He was appointed to Rome in 1938. Clearly Arthur Griffith held Michael MacWhite in high esteem and indeed the evidence suggests he had plans to encourage the Corkman to become involved in active politics with a view to filling the role of Minister for External Affairs. Unfortunately, the premature death of Griffith in 1922 meant that these ideas never came to fruition.

2 A Young Priest in The Vatican

Hugh O’Flaherty was born in February 1898. His father, James O’Flaherty, was from the Headford area of Galway and joined the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in 1881 at the age of about nineteen. (He is listed as ‘Flaherty’ in the records.) Having served for short periods in Longford and Mayo he moved to take up duty in Cork in 1885 where he served until 1897. During the latter years of his placement there he was assigned to the barracks at Glashykinlen. While there he met Margaret Murphy whose family farmed at Lisrobin, Kiskeam near Boherbue in County Cork. They got married in June 1897 and the following month they moved to live in Kerry as he had been transferred to a new posting in Tralee where he served for a number of years before being transferred subsequently to Killarney.

The tradition in the Murphy family, as indeed in many others at that time, was for the expectant mother to return to her maternal home so that her own mother could assist with the birth, particularly in the case of the first born. Accordingly, Hugh O’Flaherty was born in Cork. However, he would insist for the rest of his life that he was a Kerryman through and through (although he adopted a neutral position between Cork and Kerry, at least for a few minutes, when on one occasion he was honoured with the invitation to throw in the ball at a Munster Final).

James O’Flaherty resigned from the RIC in 1909 to take up the position of caretaker and caddy-master at the Killarney Golf Club which was then located at Deerpark on lands donated by Lord Kenmare, the major landlord in the area. The O’Flaherty family lived in the front lodge on the property, so essentially they had access to the golf course every day. This is where Hugh’s lifelong love affair with the sport of golf commenced. He turned out to be fairly expert at the game, managing to get his handicap down to low single figures, close to scratch.

In 1913 Hugh found himself involved as a witness in a court case. Three women came to hold a meeting in Killarney as part of the suffragette movement. They applied for permission to use the Town Hall but were told it was not available. They got a similar response from Lord Kenmare when they applied for permission to use the Golf Clubhouse, so they ended up holding their campaign meeting in the open air. The day after the meeting, the Golf Clubhouse burned down. James O’Flaherty gave evidence that he went to bed shortly after 11.00 p. m. and when he woke at 5.00 a. m. the clubhouse was burning. Hugh gave evidence that the Club Secretary left at 6.30 p. m. the previous evening and there was no sign of any fire. He also said that he found a suffragette emblem on the premises. The club was awarded damages more or less to the full amount they sought in court.

At the age of fifteen Hugh secured a Junior Teaching Assistant post in the Presentation Brothers School there. Subsequently, he won a scholarship to teacher training but failed his Diploma examinations, most likely due to a bout of illness which interfered with his studies towards the end. However, during all of this time his ambition was to join the priesthood. He was concerned that the pursuit of this vocation would place additional financial hardship on the family and was nervous of approaching his father on the matter. He decided that the best course of action was to enlist the assistance of his only sister, Bride, who, it would seem, was ‘the apple of her father’s eye’. He need not have worried. When Bride approached her father, his response was, ‘I would sell the house to make a priest of him.’

He successfully applied to Mungret College in Limerick which was an institution run by the Jesuit Order preparing young boys for the priesthood on the missions. He joined Mungret in 1918. While he made excellent progress in his studies, he was more noted for his prowess in the sports area: golf, handball, hurling, boxing and swimming were among his favourite pastimes.

This was a difficult period in Irish history and the young students in Mungret were well aware of the various atrocities being committed by the occupying British forces at that time. Indeed, O’Flaherty’s father resigned from the RIC, like many of his colleagues, rather than find himself in confrontational situations with neighbours while fulfilling his duties. Hugh himself had a brush with the law in 1921. He and two of his colleagues had walked from Mungret into Limerick to pay their respects at the houses of two prominent citizens who had been shot the previous night. On their way home, all three were arrested and held, until released at the request of the Rector of Mungret College who had been tipped off that his students were in difficulty.

Later in 1921, O’Flaherty was sponsored by the religious authorities in Cape Town, South Africa, and sent to Rome to continue his studies. He was assigned to the Propaganda College whose objective was to prepare young men for work in the missions. During his time there he distinguished himself academically and he qualified in 1925. He was ordained by Cardinal van Rossum on 20 December 1925 and celebrated his first Mass the following day.

His correspondence home to a range of family members during these years highlights the characteristics and values which he brought to bear on his subsequent work. Particularly noteworthy are his humility, a gentle nature, care and concern for others (most particularly his parents), the strength of his vocation, a sense of humour and a willingness to help anyone – whether relative, friend or distant acquaintance – who might be visiting Rome. In addition of course he kept his family up to date on his developing career and was always anxious to hear news of home. For example, he wrote to his sister in July 1925 regarding his success in the examination for the Licentiate in Theology (L. S. T.):

I just ‘flucked’ [fluked] through and no more – the narrowest shave I ever had … I was fortunate to slip through … I went in for the exam in the evening … with a cold perspiration all over because five went in that morning and only one got through the ordeal with success! Even the two Irishmen before me fell and here was I the sole hope of old Ireland and Mungret going in to try and lift the flag from the dust. Four professors were before me but only three can examine. For the first two I did splendid thanks to the prayers of many friends and St Theresa. But the third went well for half time and he glued me to the chair with rockers and the others helped him to crush and reduce the points which were mine in the beginning … However, they gave me the Degree and I have it.1

He contrasts his success in the Degree examination and the consequent entitlement he now had to place three letters after his name with the importance of his vocation:

But there are also three letters before Hugh! ‘Rev’ after July 12th. It was a great day and as usual when I am happy and the Lord showers blessings on me, then instead of laughing and thanking Him I cry, which of course is mother’s weakness.2

He then advises his sister that he was thinking of going on for a Doctorate in Theology.