4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

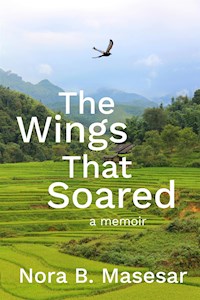

- Herausgeber: Nora B. Masesar

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Dreams, no matter how far-fetched, can be achieved with faith and determination.

This memoir is a life’s journey which started with a happy childhood spent on the rural farm in the Philippines in the 1950’s.

Nora’s idyllic life turned into a constant struggle when her father left them. Their family was reconciled, but the journey was of hardship, difficulties and sufferings when she was growing up. This made Nora aim high. The struggle continued through the years of hard work, marriage, having children and a work venture in Taipei. This is not the kind of life she wanted for her children. Nora made up her mind to leave the homeland that was dear to her.

She settled in Australia and travelled the world, but the recurring dream of returning to her birthplace has made her wonder. Has she chosen the right path?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

About The Wings that Soared

Dreams, no matter how far-fetched, can be achieved with faith and determination.

This memoir is a life’s journey which started with a happy childhood spent on the rural farm in the Philippines in the 1950’s.

Nora’s idyllic life turned into a constant struggle when her father left them. Their family was reconciled, but the journey was of hardship, difficulties and sufferings when she was growing up. This made Nora aim high. The struggle continued through the years of hard work, marriage, having children and a work venture in Taipei. This is not the kind of life she wanted for her children. Nora made up her mind to leave the homeland that was dear to her.

She settled in Australia and travelled the world, but the recurring dream of returning to her birthplace has made her wonder. Has she chosen the right path?

To Davis and Daina and in loving memory of my parents, brothers and sister.

Contents

If Winter comes can Spring be far behind? – Ode to the West Wind

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought. – To a Skylark

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prologue

Faith and determination have shaped my destiny. This is a story about a life’s journey from childhood to adulthood which shows that dreams, no matter how far-fetched, can be achieved.

The story starts with my childhood spent on the farm in the Philippines. We had a simple life. On the farm we children had awesome and daring escapades. We lived close to nature and learned the basic skills of survival. My primary education was wonderful. It taught me how to become an achiever.

I consider my childhood the happiest years of my life. It was a time of innocent bliss where nature abounded and no rules applied except the discipline of our parents and teachers. I was always with my elder brother and sister who were also my closest friends. Our escapades are worth remembering. We were together as a happy family – until something happened that changed it all. After my primary schooling, our life was hardship, suffering and struggle for survival.

This book also describes how I faced and surmounted obstacles in my life; how I looked at life differently; how I appreciated the beauty of the many blessings I received despite the difficulties – my travels to Asia, America, and Europe, the lessons I learned from the people I met; how we lived our life in Australia; the humour in some experiences; and how God has shaped me to be who I am.

I have accomplished something that I am proud of. Through sheer determination and a strong focus on my goal, I was able to leave my homeland and venture to foreign countries where I knew no one.

I went through a traumatic divorce, deaths in the family, two retrenchments and finally, I have reached a time of freedom to enjoy life. After my divorce, I couldn’t look back without tears in my eyes. I remembered all the sorrows. My grief made me emotionally fragile. It hurt me deeply despite my determination to move on. I chose to switch off certain parts of my life, to blot out the hurt that had not abated despite the long years of trying to move forward. As the years went by and as I became older, I gained a mature acceptance of what happened. I began to set aside my emotional baggage and really started living. I discovered that happiness is not at the end of the journey, but it is the journey itself.

I could have done things differently. But it was my life, my journey and I did it my own way. I have no regrets. In this memoir, I express my feelings as I discuss each passage of my life. The aim is not to please everyone.

I abided by the strict rules and guidance of my parents. I was obedient, I followed the rules, but that is over now. I am proud of what I have accomplished and of what I have become. I must have inherited my mother’s resilience and wisdom and my father’s courage and determination. The legacy of my parents’ wisdom, especially my mother’s, has been handed down to my children. I hope it will be handed down to the next and future generations.

My brothers and sister – Kuya Tito, Ate Vernie, Frank and Benjamin – are gone from this life. They were brave because they knew they were dying, but they faced the eventuality of death. My father and my mother have also passed away, but their legacy of love, strength and determination lives on. As devastated as I was at the loss of loved ones, I knew life had to move on. And so must I.

Chapter 1

I was born in Madong, a small barrio in Janiuay, Iloilo, Philippines. Iloilo is one of the islands in the middle part of the Philippines called the Visayas. We lived on the farm my father tilled. Seven of us brothers and sisters were born on the farm, delivered by a midwife. Only my younger brother Frank was born in the hospital. I was the third child in the family.

My father was a jack of all trades. He was not only a farmer but also a carpenter and a merchant. He was ingenious and resourceful. His innovations made the work practices of most of his co-farmers in the surrounding barrio pale in comparison. My father’s ingenuity brought much meaning into our lives.

The happiest days of my life were spent on the farm. I was always close to my elder brother and sister. It was a time of pure bliss and innocence. We were free to roam the fields, climb trees, explore the rice fields, go to the creek where we swam and caught fish, play hide and seek and devise our own games to entertain ourselves. We had no fear of exploring our surroundings because we felt safe in our neighbourhood.

Madong was a small barrio where everyone knew one another even if they were kilometres away. We enjoyed just being children and had a life full of fun. We were close to nature, the trees, animals and insects. We were free to play and do our own thing, so long as we pay heed when Nanay, our mother, called us for lunch or dinner – otherwise we’d be in big trouble.

The Masesar land in Madong was 2.3 hectares. It was sold to the Maranon family and the proceeds of the land were divided between the Masesar brothers and sisters. Uncle Hugo, the eldest in the family, took his share of the proceeds and went with his family to Mindanao Island in the south of the Philippines. There he established a trucking and logging business. A few years later, he sold the business and took his entire family to Canada. The remaining brothers and sisters stayed in the Philippines. My father, Tatay, took his share of the proceeds from the land sale and remained in Madong. He leased the land sold to the Maranons and also tilled adjacent lands in Tuburan, leased from a Chinese man called Apoy Wong. Tatay tilled these farmlands mainly as rice fields divided by rice paddies. He employed people to help plant and harvest the rice.

We elder children helped with the farm work. Kuya Tito, Ate Vernie and I were not exempted from the hard work as Tatay always needed a helping hand to work on the land he tilled as well as looking after the fields of vegetables and fruits for our needs. We also helped with the poultry, in the piggery, and in all aspects of farm work to sustain our livelihood. Nanay’s older nieces and nephews helped her look after us children while she devoted her time to managing the day-to-day activities of domestic work – cooking, cleaning, laundry and helping my father in the management of the farm.

Tatay was ingenious. Whatever he did had to be perfect, including farming. Tatay applied the Masagana system of planting rice. It was a 12 by 12 planting layout, so from whichever angle you looked at it – vertically, diagonally or horizontally – you could see a straight line between the rice seedlings. This method proved to be the best system for rice farming. Our rice production at the end of the harvest was always plentiful.

The rice seedlings we planted came from the seedbeds that Tatay planted before the start of the planting season. When the seedbeds were ready for planting, he hired workers from neighbouring barrios to plant the rice from morning till dusk. It was a joy to look at the rice fields, neat in their patterns, when the planting season was finished. The Masagana system allowed the rice to grow tall and abundant. If there were weeds, they were easy to spot, giving Tatay time to eradicate them before they grew into the planted rice.

The Filipino folk song ‘Planting Rice is Never Fun’ describes this hard work well.

Planting rice is never fun

Bent from morn till the set of sun

Cannot stand and cannot sit

Cannot rest for a little bit.

The Tagalog version has a second verse which goes like this:

Sa umaga pagkagising

Ay agad iisipin

Kung saan may patanim

Duon may masarap na pagkain.

Roughly translated, this means as soon as you wake up in the morning think straight ahead to rice planting. It is where you will find delicious food.

Some say planting rice is discouraging because it is never fun. Actually, this is true. As the daughter of a rice farmer I know that planting rice is hard work, a back-breaking job, but a job that has to be done. You cannot stand and cannot sit; you just bend to plant rice in the soft muddy soil. The only chance to stand up is to collect more bundled rice seedlings from the rice beds or take a lunch break.

Nanay would rouse us at around 4 am to go to the rice fields. She’d survey the fields and point to the area where we had to start planting rice as the day broke. Sometimes we were out planting rice before the sun rose as it’s too hot when the sun is up. If Tatay hired labourers, then we children were expected to go with the hired hands to plant rice with them. Tatay had the rice seedlings ready and bundled before the day of planting. The hired planters did not need to pull them from the seedbed when they arrived.

We ploughed the fields in rows before the planting day. This guided the rice planters as to where to plant the seedlings in a uniform manner. They could easily push the seedlings deep into the soil in a straight line. Our working carabaos (water buffaloes) were harnessed to pull the ploughs. Usually, twenty or more workers came during the day, the men taking turns to plough the fields. This enabled us to finish planting rice quicker and cover several paddies. Rice planting was done during the rainy months. The monsoon rains usually start in June and continue until August.

I was young and little, but I ventured into the rice field holding a plough. The only problem was the water buffalo got impatient with me because I was so awkward handling the reins. We always ended up in disaster. I often lost control and plunged into the mud while holding onto the rope pulled along by the water buffalo – without the plough. For anybody watching, it would have been hilarious. Ploughing rice fields was a great experience for me but also exasperating. I had to try several times to get it right but even at a young age, I did not give up easily. I was lucky if I ploughed a whole row without mishap. This, for me, was a great accomplishment – something to brag about to the family.

The worst part of planting rice was touching the worms attached to the seedlings and the leeches that clung to my legs and arms and sucked my blood. The leeches were slimy and difficult to remove as they clung hard. They would fall if a pinch of salt was rubbed on them, but we did not have that luxury in the field. It was usually my elder sister who came to my rescue to remove these parasites when I screamed my head off in panic and disgust. But this was part of farm life. Despite my revulsion, I had to keep going and finish the work. We had to finish our assigned tasks. With this responsibility in mind, I accepted the hazards despite my fear.

The best part of all this hard work was when we rested and ate lunch or took our mid-afternoon snacks. Nanay’s role was to feed us. Lunch consisted mostly of rice, fish and vegetables. Tatay or Nanay would go to the markets to buy fish and other provisions for us and the workers who helped us plant the rice. This was in addition to the fish we caught from the river and the freshly harvested vegetables from our gardens.

Alternatively, a pig would be slaughtered to supply our meat during the planting season. We had chickens from our poultry shed and ducks from the ponds if Tatay had no time to slaughter a pig. For our merienda (teatime), we had guinatan halo-halo, a mixture of sweet potatoes, ripe native banana, purple taro called ube, tapioca and ripe shredded jackfruit flesh to give the guinatan a beautiful flavour and aroma. If tapioca wasn’t available, we made small balls called bilo-bilo out of glutinous rice. This delicacy was cooked in coconut milk and brown sugar. When the guinatan was nearly cooked, the coconut cream was added to thicken the consistency. It was yummy and very filling – one of my favourite snacks.

We occasionally had puto, made of ground glutinous rice. We poured it into a round tin with a banana leaf at the base and cooked it over burning coals. When the puto was cooked, it was topped with freshly grated coconut. If Tatay had time to go to town to buy groceries, we had margarine to spread over it. It just melted on top of the delicacy when hot, making the puto a mouth-watering snack. Another variety of snack from this ground glutinous rice is palitaw. Literally, it means floating. This is a flattened oblong lump of ground glutinous rice dropped into boiling water. When it floats on top of the water, it is cooked and ready to be taken out. We dip this palitaw in sugar with sesame seeds. For added flavour, we sprinkle it with freshly grated coconut. We also had bibingka made out of whole glutinous rice cooked in a clay pot. Nanay mixed it with coconut cream and brown sugar and cooked it in a big wok (we had no ovens then). When it was cooked, Nanay would flatten the bibingka on a wide circular shallow basket covered at the base with banana leaves. Then she made crispy coconut bits to sprinkle on top. These home-made delicacies were cooked freshly each day to give a variety of snacks for the hard-working people planting rice in our fields.

Tatay was the sole supervisor of our rice growing. If there were weeds between the rows of the planted rice, we helped him pull them out. Eventually, due to the large area of land that Tatay tilled, he used chemicals to eradicate the vicious weeds without affecting the growing rice. At harvest time, Tatay hired the same people who helped us plant the rice. Some of them were from neighbouring barrios.

When we harvested rice, the male workers used a big scythe to cut the rice stalks before bundling them. The women and girls used a small scythe wedged on a bamboo stick tied to our right hand – just the size to fit into our hands. We women were slower to harvest rice this way because we cut the stalks near the rice grains and it was harder to bind them into bundles. The stalks were shorter, but our harvested rice was tidier than the men’s bundled ones with long stalks that included weeds with them. We used a salakot (a triangular hat made of bamboo slats) to protect us from the heat of the sun. We bound this hat with a bandana tied around our necks so it would not fly when the wind blew.

Before sundown, we all carried our bundled rice to the place where Tatay had spread several mats made from nipa leaves. We placed the bundles of rice on these laid-out mats and stayed with our bundles until the harvested rice was accounted for. Hired labourers got bundles of rice as payment, depending on how much they had harvested. One variety of rice we grew was tall. The wind swept them in one direction when the rice was heavy with grain. They stayed in that direction until they were ready to be harvested.

If I remember right, the ratio of sharing the harvest was 3:1. One bundle went to the landlord, one bundle to us who managed the farm, and one bundle to the worker. Our share was the same ratio as the workers. I don’t know whether Tatay got an additional share from the landlords. They were well-off. One was a wealthy Chinese businessman in town. The counting of and accounting for the harvested rice was done daily. The share due to the landlord was placed in our rice granary. When the granary was filled, the landlord would come to take his share of the harvest.

We processed our share of the harvest manually. We used our feet (linas) on a big mat or in a tub to remove the grains of rice from the stalks. When we finished, we spread the rice grains on big mats to dry under the sun. When the grains were dry, we removed pulp from the rice with a pestle and mortar. Afterwards, we used a flat round basket to sieve the skin from the clean rice. Because it was hard work and it took time to do this, we processed just enough for our immediate use. Tatay went to town to process the remaining rice. This was how we had sacks of rice stored in our rice granary and used for our staple food supply until the next harvest season.

Chapter 2

My father, Leon Masesar, was given the award of First Farmer of the Year in the 1950s. The Bureau of Plant Industry, now part of Department of Natural Resources, gave the award to my father for producing 240 cavans of rice per hectare, making him the highest rice production farmer in Iloilo province. A cavan was a Spanish unit for measuring rice in the Philippines. There is no exact equivalent in current measurements but a near approximation would be around 50–56 kilos per cavan.

Between the rice seasons my father, with the family’s help, planted maize or corn, sweet potatoes, cassavas, peanuts, pumpkins, other root crops and vegetables, and fruit for our consumption to sustain us during the year. Tatay bought additional rice from town if our harvest during the rice season was insufficient. This might be due to unforeseen events like locust infestation or flooding that destroyed our rice production.

Tatay carved our mortar and pestle from a big tree trunk. The mortar resembled a small boat (approximately 140" x 40") with a big smooth round hole in the middle. The long pestle had a grip in the middle with round ends on both sides so that either side could be used. We normally had two pestles. When there was a lot of rice to pound, two people used the pestle alternately to finish the job quickly. The same thing applied when we wanted to make delicacies that required mixing ingredients. Both flat ends of the mortar were a convenient place for us to put plates, cups and ingredients like additional soft green rice (pinipig), bananas, grated coconuts and red sugar for the delicacy we were making.

Tatay also made a big round stone grinder to grind our corn and rice. One heavy round stone was placed on top of the other stone with a space between them. There was a hole in the middle where we poured the grains of rice or maize. We rotated the pulley handle attached to the top of the upper stone to grind the rice or maize that had been wedged between these two stones. The finer grains flowed into the concave tunnel carved on the lower stone. Then it fell onto the round flat basket on the floor which caught the grains.

Whether we used the pestle and mortar to remove the pulp of rice grains or use the grinder stone to grind, the process of making the rice grains ready for cooking was hard work. On the other hand, it was fascinating to learn this crude, manual way of doing things. (I found that mixing the ground grain of corn with the newly harvested rice actually tasted good.)

As jack of all trades, Tatay was also our medicine man. Whenever we had a wound, he would scrape something from a yellowish stone which he said had a curative effect. Indeed, it did, as the wound healed quickly when this powdery substance was administered. I know now that the yellow stone was sulphur.

One time Kuya Tito, Ate Vernie and I were running around, playing in our earthen yard. I stepped on a rusty nail and it was imbedded in my left foot. I must have screamed loudly because Tatay and Nanay were with us immediately. I was lucky they were home and not working on the fields. Tatay cut an incision on my foot, squeezed out a lot of blood, poured alcohol and Mercurochrome (equivalent to iodine) and after drying the wound, scraped a lot of match heads on the wound and lighted it. The only thing I remembered was circumnavigating the entire balcony area on my bottom while holding onto my foot. I can’t remember what else was done to it, but my wound healed quickly. I walked around with a bandaged foot for a week and that was it! The bandage we used was a strip of calico or white cloth tied around the wounded area to protect it from infection and dirt. We didn’t have disposable bandages. After that, I never walked barefoot. That must be why at a young age, I was the only one in the farm who wore wooden sandals every day, and the only one who wore them at school. Most of my classmates went barefoot.

Tatay had a healing hand. He knew the pressure points to massage when we weren’t feeling well. News of his healing gift spread in the barrio. Some of our neighbours asked for his ministrations if they wanted to get well. Tatay used a sweet-smelling oil after the massage, either coconut oil we made ourselves or Efficascent oil that he bought in town.

Living on the farm meant living close to nature so a lot of unusual things happened in our daily life. I remember the day my younger brother Ben was placed inside a big wooden basket which served as a playpen. We were working in the fields planting vegetable seedlings in the newly ploughed rows. Tatay was always particular about how to plant crops so as to produce the best harvest. We were farther down the field when we heard a loud scream from the basket. We all ran back to see what had happened. Nanay pulled my brother out from the basket. She was nearby minding him but she was also busy planting seeds like us. All we saw when we came to the rescue were a lot of red ants that had bitten my brother, crawling inside the basket. No wonder he screamed loud and shrill.

On the farm you could see lizards crawling, some of them with beautiful colours. The largest ones were called tuko because they made this onomatopoeic tu-ko sound at night-time. You couldn’t see where they were hiding but could hear them. Sometimes they crawled out from their hiding place, and we saw how big they were. They weren’t dangerous, so we lived in peace with them. Nanay told us of one instance when she saw a green snake curled up on top of our mosquito net when she woke up one morning. She only shooed it away as we didn’t kill these creatures. They were part of our farm existence. The rats and mosquitoes were different because they were pests. Rats ate our rice. The mosquito bites were itchy and dreadful, so they needed to be eradicated. I was not aware of malaria during our time.

Life on the farm had taught us how to survive and become resilient by learning basic skills. I learned to cut wood using an axe; learned how to build a fire without a match using the sun’s rays; fetched water with a pail from the well, and later on filled hollow long bamboo poles with water. I could never balance a water jar on my head so that was out of the question. I was too unstable and not still enough for such a task.

I learned to dig cassava roots, sweet potatoes and other root crops. It gave me the creeps though, when I happened to dig the big worms underneath the soil. When we worked on our vegetable garden, we used spade, rake, hoe and pick. We didn’t have garden gloves. We fetched water from the well that Father dug for us to water our plants and crops. It was hard work, but we couldn’t wait until the rain watered them. We had tropical weather so when it rained, it poured. We looked forward to it as it was the best time for us children to clean ourselves. We splashed water around and enjoyed the strong downspouts on our heads from the roof gutter. It was fun! It also meant that we didn’t have to fetch water from the well.

Tatay had a catchment that channelled the water to the big drum he propped up on a platform with wooden walls to secure it. It had a small tap at the bottom, so we needn’t go up the ladder to get water. After the rain, the best pastime for us children were to fish in the stream down the road. It was a joy to catch fish and sometimes shrimps that wriggled in our nets until Nanay cooked them. If there was flood after a storm, we explored the following day. The rice fields overflowed with water and looked like a lake. We were careful to only walk on the roads because the rice fields were deep and there was no sense getting stuck in the mud in the middle of nowhere with no help at hand.

Our house was a traditional nipa hut, made of nipa leaves and bamboo poles. This was typical in the Philippines and part of Filipino culture.

Tatay built our house large enough to accommodate us seven children plus the live-in helpers, one handyman and two of my elder female cousins on Nanay’s side. The entrance to the house on the ground floor led to an earthen lounge where there were long bamboo benches made by Tatay. Midway was a ladder to the upper floor with an open wide lounge room. On both sides were rooms divided by thatched walls. The main bedroom on the right belonged to my parents. We children slept together in the spacious lounge room. The door leading to the left led to a long wide space and a balcony overlooking the rice fields. The flooring on this upper level was made of bamboo slats and the walls were thatched with bamboo frames. The windows opened outwards. During our time, our furniture was basic – wooden or bamboo chests, chairs, long benches, a rocking chair and wooden beds.

Most of the household things were kept on the ground floor. Our rice and corn stone grinder were there. Near the back of the house was the granary where Tatay kept our rice supply. Tatay’s farming and carpentry materials were also on this floor. The flooring on this area was just the natural earth. Our pestle and mortar carved from a big piece of wood was near the kitchen. Further down the hall, we had an elevated kitchen built of bamboo slat flooring and thatched walls. The windows here also opened outwards. We used clay pots for cooking rice and fish, and steel pots for vegetables. We had a wok for frying. We placed banana leaves at the bottom of the pots to prevent the food from burning. The pots either sat on holes held by four crossed steel bars on top of the fire or on a cement stove with holes on top of a burning fire. We lit piled sticks and chopped wood at the bottom of the pots to make a fire. The charcoal produced from these pieces of wood and sticks was gathered to fill the iron if there was ironing to be done during the day. On either side of the ladder going to the kitchen was a door. The right door led to the side of the house where we could go under the house and out to the flower garden. This was also a way of going out onto the earthen road Tatay built for our use. The left door opened towards fruit trees. On this side were the duck pond and the pigpen. The chickens were on another side of the house protected by wire mesh.

Fresh vegetables came from our gardens. We had all types of vegetables. The song ‘Bahay Kubo’ includes the kinds of vegetables and crops that surround a farmhouse. Some of the varieties of vegetables can only be found in Asia. We also had different varieties of bananas – my favourite was called saba, a squarish variety. When it’s ripe, you can eat it raw, boiled or mixed with other ingredients to make guinatan halo-halo.

Around the house were trees that provided us with ample fruit. Different trees bore fruit at different times. We had several varieties planted a few metres away from the house to cater for each season. There was an abundance of papaya (paw paw) trees with fruit that grew in clusters. We used the green ones as a vegetable in chicken stew, seasoned with ginger and chilli leaves. When they were ripe, they were eaten as a normal fruit. Sometimes we added condensed milk to make an afternoon snack or a dessert.

Tatay had a separate elevated field for our fruit and vegetable crops. We loved helping Tatay plant the vegetables and root crops. There were lots of pumpkins, sunflowers, sweet potatoes and all sorts of fresh vegetables and root crops in the field including ginger, garlic, shallots, tomatoes, eggplants, snake beans, peas, bitter gourd, sesame plants, carrots, peanuts and cassavas. Our vegetable field was near the water well that Tatay dug. This was where we fetched drinking water, where we took showers, laundered clothes and watered the crops. Tatay made a dirt road for us from the well to the house. He demonstrated ingenuity in all these things.

We were young, so it was hard for us to fetch water from the well, carrying a pail in each hand. Most of the time we spilled half the contents before we reached the house. To enable us to fetch water from the well without mishap, Tatay made us big long bamboo poles. He removed and cleaned the inside mid-section of a big bamboo pole to enable the water to go through to the bottom, leaving the end intact to hold water. It was easier for us children to fetch water this way because we could put it on our shoulders, switching from one to the other.

Our corn had a field separate from the other crops. We delighted in dropping corn or maize seeds on ploughed areas of the field during the dry season. Sometimes Tatay got seeds of different varieties of corn. As well as yellow corn, we had mixed white and yellow corn, which was soft to bite and had a glutinous, sticky consistency when cooked. When it was ripe, we loved picking the ears of the corn. Mostly, we boiled them for a nourishing snack. I loved the yellow hair of the corn, so I gathered them to make a pretty doll with yellow hair. I made my doll out of gingham cloth stuffed with kapok, a cotton-like substance. I drew the eyes, eyebrows, nose and lips with coloured pencils before sewing coloured thread over my drawings.

Our papayas bore fruits in clusters. The green ones we cooked with chicken and Moringa leaves we call malunggay, a plant with leaves shaped like a four-leaf clover. This vegetable grew in abundance. We usually washed it and ran our fingers through the stem to scrape the leaves. We needed a container full of these leaves to have enough leaves to cook with chicken, green papaya and fresh ginger. We called this dish tinola and the soup was a very effective treatment for a cold. When the papayas ripened, we ate them as a refreshing snack. Our papaya varieties are very sweet when ripe.

The banana trees planted on the rice paddies were big and numerous and produced better fruits than those on the higher land. We had different varieties of bananas.

There were pomelo trees in front of the house and a star apple tree called kaymito. Kaymito fruit when ripe is a green round fruit with soft white flesh. There is also a purple variety. We scooped the soft flesh with a spoon, or just broke the skin and sucked the white flesh. The star apple tree has a sticky white juice that is hard to remove because it sticks like glue. When we had a stomach upset, we boiled the leaves of this tree and drank the juice to stop diarrhoea. It worked like a Kaopectate medicine.

There were chicos (Sapodilla, a brown round sweet fruit) and different varieties of guavas near the road to our house. The fruits of the native ones were small and hard, but the imported varieties, especially the Indonesian one, had large, sweet fruit. We had seneguelas (a small round fruit which was a greenish-purple colour when ripe), camachiles (a tamarind-shaped fruit with a bland taste and colour ranging from green or yellow to purple when ripe) and balimbing, a fruit which tastes sweet-sour and looks like a star when cut horizontally.

We also had jackfruit trees which yielded a lot of fruit. We cooked the green, raw ones as a vegetable. It tasted nice with a slice of pork or shrimp, with coconut cream and chilli to season. When the jackfruits were ripe, they emitted a beautiful aromatic smell. We removed the flesh from the spiky skin to eat or used it to flavour teatime delicacies like guinatan. We also sprinkled shredded pieces of ripe jackfruit over bibingka. The seeds were boiled and eaten as nuts. They were soft and fleshy, like chestnuts. We had avocadoes and guayabanos too. Guayabano fruit looked like custard apples. It had spiky skin and a sweet-sour taste when ripe.

Our coconut buko trees were on the opposite side of the road from our house, bearing large clusters of coconuts. We had a kapok tree that we used as stuffing in our pillows. It was fun harvesting the fluffy white cotton from the kapok tree, although it made us sneeze.

Chapter 3

Our food mainly consisted of rice, vegetables and fish. We had corn, cassava, squash (pumpkin) and kamote (sweet potatoes) growing in the fields for food supplements.

The fish from the markets were always fresh. My favourites were galunggong, sapsap, tilapia, anchovies, sardines, bilong-bilong and shrimps. Nanay could make delicious fish dishes just using salt, tomatoes, ginger and seneguelas or gabi (taro) leaves. Sometimes she fried the fish with a sprinkle of salt. She cooked shrimps with saluyot (a native green leafy vegetable) and freshly grated bamboo shoots. This tasted good with coconut milk or cream and small red chillies. The red and green chillies were grown in our backyard. We cooked milk fish (bangus) in different ways. Nanay prepared fish simply – she either cooked it with green leafy vegetables, onions and tomatoes, making a soup, or grilled it in charcoal wrapped with banana leaves and seasoned with finely chopped tomatoes, onions and ginger stuffed in the slit stomach of the fish.