13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

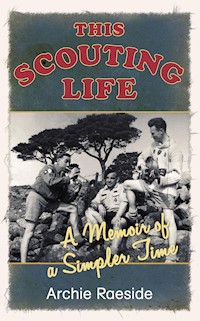

Exploding tins of beans over a campfire. Hammering down tent pegs in the rain. Marching for hours, singing for days, and playing 'Bulldog's Charge' at every opportunity. This Scouting Life is a story about the experiences shared by millions of people worldwide, and in communities all across Ireland. For the author, Archie Raeside, this is the story of how an eight-year-old boy in Dublin of 1947 decides he wants to become a Scout and how that desire becomes a reality. As the author rose through the ranks, his memories paint a picture of a changing organisation and a changing Ireland, recounting his involvement with Presidency of Eamon De Valera and the visit of Pope John Paul in 1979. This is a book that tells the story of one man's life within the Irish Scouts, but in the memories he evokes and the scenes he recaptures, this is a book about a simpler time of which we were all a part.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

1 Why Scouting?

2 35th Dublin, Early Years

3 The Scouts

4 Annual Camp

5 The Knight Errant Clan

6 National Revamp

7 Fiftieth Anniversary

8 Air Scouting

9 Growing Interest

10 A New Roles

Plate Section

Copyright

1

WHY SCOUTING?

Standing just head and shoulders above the living room windowsill, I watched and waited excitedly for Bill and Brendan Lawlor to come intoview. While they were still a good distance away I knew it was them, because Bill, the older of the brothers, was wearing a distinctive Scout hat which looked just like a Canadian Mountie’s. ‘They’re coming,’ I called out and Mammy came through the kitchen door urging me to contain my excitement. It was more polite to wait until they came up the garden path and knocked on the hall door, Mammy said. ‘We’ve come to take Archie to the Scouts,’ said Bill. Mammy thanked them, and we set off to what was to be my first Cub Scout meeting, and the start of over half a century’s involvement. This was 1947.

I’m not sure why I wanted to join the Scouts. Football and hurling at school and being an altar server at the local church somehow did not seem enough though, and Drimnagh, where I lived at that time, had few organised facilities for young people. I think I was looking for something more interesting, or perhaps it was the fact that my father had been a Scout in Scotland for a number of years. His first visit to Ireland was with his group of Rover Scouts. Perhaps I was influenced by pictures in the family photo album of him and his mates camping at Powerscourt Demesne. At seven years old the idea of travelling to remote areas to experience living in a forest or on a mountainside appealed to me and this was what the Scouts seemed to offer.

My parents had obviously made enquiries as to the whereabouts of local Scout Troops and the closest to our house was at Merchants Quay, about three miles away. There were so few troops established that my name went on the waiting list. Mother had befriended a Mrs Lawlor who lived close to our church and discovered that her boys were in the Scouts attached to the parish of Donore Avenue. So it was that I now found myself on my way with Bill and Brendan to the Scout hall.

Although the troop, known as St Theresa’s Troop 35th Dublin, was founded in Donore Avenue nineteen years earlier, the meeting place would change many times in its long history. Fr Valentine Burke, head curate of St Theresa’s church, Donore Avenue founded it in 1928. The first Scoutmaster (now termed Scout Leader) was Mr Jack Giltrap. He was a former Baden-Powell Rover Scout. He had long left the unit when I joined but many years later I would meet up with him, as we both worked for the same company (Fry Cadbury) for a few years. At that time it was usual for Protestant boys who had a spirit of adventure to join the SAI (Scout Association of Ireland) or the Boys Brigade (BB), of which my uncle Ian and cousins Bobby and Duggy were members. Catholic boys with like-minds joined the CBSI (Catholic Boy Scouts of Ireland). We referred to the SAI as Baden-Powell Scouts. Of course we were all following in the great tradition of the world brotherhood of Scouting as envisaged and established by Lord Baden-Powell.

It is generally accepted that, sometime in 1928, Fr Burke acquired the use of the Little Flower Hall in Meath Street for troop meetings and, under his aegis, the troop was well provided for. He was known locally as ‘Toucher Burke’ because of his ability to extract money for any useful purpose. There is a story about a child who swallowed a halfpenny and after the doctor was unsuccessful in removing it, neighbours advised his parents to take the child to Fr Burke because he could get money out of anyone. In 1947, Fr Burke was appointed to the National Executive of CBSI.

About this time, however, he was transferred as parish priest to Cabra West and lost to our unit. Following his departure, notice was given to vacate the Little Flower Hall. With this began a period of moving about from one meeting place to another, and it was also, more significantly for me, the point at which I became an official member.

With the Lawlor brothers as my escort, we crossed the bridge near my house, then a short distance along the canal tow path and over the footbridge at the 2nd Lock. Now in Inchicore parish we hurried along Connolly Avenue on to Emmet Road, then turned right on to Grattan Crescent at the north end of Tyrconnell Road. The final leg of the journey was along Inchicore Terrace which led to the Inchicore Railway works. The troop had acquired the use of the railway dining hall for their meetings. The troop had two sections then: the Cubs (known as the Cub Pack) and the Scouts.

Once inside the Den, Brendan, who was Senior Sixer’, introduced me to the Cub Master, Mr Healy. Leaders’ surnames were prefixed with ‘Mister’ or they were addressed as ‘Sir’ back then, and it would have been considered cheeky and even disrespectful to use first names when addressing adults.

To become a member of the ‘Pack’ it was necessary to be eight years of age or to have made your First Holy Communion, and to pass a few tests. I soon learned the promise, the principles and the Cub prayer. So as to be ready for the ‘investiture’ ceremony it was also necessary to learn ‘foot-drill’. The weekly meetings began with the Cub prayer followed by collection of subs, which were only a few pence, and then an activity game.

The games varied from week to week and were designed to heighten our senses and develop physical strength. ‘Snatch the Bacon’ or ‘Pirate Chief’ was always a firm favourite. After lining up to form three sides of a square, one blindfolded boy sat in the centre of the fourth side with legs crossed. From the beginning of one line, each in turn called out his position until everyone had a number. One of the leaders then placed a Cub cap just in front of the seated player; this represented the bacon. When a number was called out, the challenge was for the selected player to reach and ‘snatch the bacon’ and return to the line before being pointed at by the blindfolded player known as the pirate. To do this there had to be absolute silence so as to be fair to the pirate chief in detecting the approach of the thief and also to test the dexterity of the later. If pointed at, then the thief took up the position of the pirate.

‘The Box’ was a bit more physical. A large circle was formed by holding hands and a box was placed in the centre of the circle. The leader then called out ‘To the right!’ or ‘To the left!’ and the entire circle of players, still holding hands, ran as fast as they could. At will, the strongest players pulled those nearest them towards the box and if made to hit the box that player was out. Should two players loose their grip during the run, then they were both out.

The game ‘Bulldog’ also required everyone to be ‘numbered off’ and this time the participants lined up across the room. One player, the bulldog, was chosen to stand facing the group some distance away. The bulldog called out a number and that player had to reach the opposite end of the room without being caught. If the bulldog failed to catch the player, then the entire group raced to the other end of the room. The bulldog then had a second opportunity to catch a player or two. When caught, a player joined forces with the bulldog. Eventually there would be only one or two left against the rest and there was seldom an outright winner.

After these physical games, we were happy to take instruction in first aid, compass points, knots or nature study. Some meetings finished with campfire songs. Everybody knew the Troop Yell and the Troop Song, as these were always a part of the campfire. The tradition of campfire singing had begun almost at the founding of the troop and was to become well known within the organisation.

2

35TH DUBLIN, EARLY YEARS

In the years preceding my involvement with the 35th Dublin, they had been active in many notable areas, not least of these being the Eucharistic Congress in June 1932 where they were involved in stewarding and providing first-aid facilities.

A huge Scout pilgrimage to Rome was organised by the CBSI in 1934 and the 35th Dublin was well represented there with fifteen members taking part. The pilgrims, led by his Eminence Cardinal McRory, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All-Ireland, travelled aboard the luxury liner Lancastria. Accompanying the group was William T. Cosgrave, TD and Sir Martin Melvin. William Cosgrave had been President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State for ten years (later to become Taoiseach) and was a personal friend of the Chief Scout, Prof. Whelehan. Sir Martin Melvin had decided to present a costly trophy to CBSI for inter-troop competition and had commissioned the leading silversmith of the time, Miss Mia Cranwell, to produce it. In a ceremony aboard the Lancastria, he formally presented the handsome silver trophy to the Chief Scout.

Each troop had a flag, ours was borne by a great Scouter, Nicky Donegan, and the array of flags obviously impressed Pope Pius XI because at the end of the ceremonies in the Throne Room, he inspected them all. When he came to flag of the 35th, he asked for it to be unfurled. Anyone who has seen this flag will know just what a work of art it was. A silk embroidered figure of St Theresa and the Little Flower by the Sisters of Charity in Donore Avenue, in the finest gold, silver and many coloured threads was featured on one side, the Scout Badge and scroll on the other. The colours were blessed on Whit Sunday 1933 by the parish priest, Canon Hayes. The following was recorded in the Catholic Scout in 1933, ‘The flag is a credit to Irish workmanship, being made by Messrs. Bull and Co. It was a gift of a few friends who prefer to remain anonymous.’ Scout Troops from Rathmines, Clonsilla, SS Micheal and John’s, Merchants Quay, Dolphin’s Barn, Halston Street and Whitefriar Street, accompanied by their bands, attended the ceremony. For forty-two years the flag was flown with pride but the long years of service caused it to need replacement. I will come to the fate of the original flag later.

Nicky Donegan became Scoutmaster later that year and stayed in that post until 1939, when, after the Second World War had started, Nicky went to Belfast on the 12 October and joined the Irish Guards, leaving for London that same night.

At Larch Hill National Campsite of Scouting Ireland, on 21 August 2004, I met veterans of the 1934 trip to Rome and many of my former Scouting colleagues. The event was organised principally for the three following reasons:

To bring together the two great Scouting traditions (CBSI and SAI) in the new association Scouting Ireland.

To celebrate the British-Irish links and friendship, which have always endured in Scouting, even in the darkest days.

To remember the tragedy of the HMT

Lancastria

and to celebrate its contribution in Scouting in Ireland and its role in securing Larch Hill for Scouting.

The connection between the Lancastria and Larch Hill is that Larch Hill was purchased largely through the profits which the Association made on the fares of the non-Scout pilgrims to Rome. At that time, 1937-8, CBSI was preoccupied with the need for a national campsite. The search eventually narrowed down to two possible locations: part of Santry Park, north of Dublin City and an estate near Tibradden called Larch Hill on the foothills of the Dublin Mountains, not far from the border with County Wicklow.

When you compare the natural and unspoiled nature of the Larch Hill site with all it has to offer young people, they certainly made the correct decision over seventy years ago.

A short history of the ship is in the Commemoration booklet prepared for the ceremony at Larch Hill and goes as follows:

The 16,243-tonne Cunard liner was built by William Beardmore & Co., Dalmuir, Glasgow, making her maiden voyage under the name of Tyrrhenia, from Glasgow to Montreal on 13 June 1922.

Refitted just two years later with a plush new interior and a new name, Lancastria, she spent many years leisurely sailing the world’s oceans. Her final peacetime cruise in the idyllic waters of the Bahamas was made in September 1939 and ended with the ship docked in New York and the world at war.

Here she underwent a radical change – her portholes were blacked out, drab grey military paint daubed all over her and guns mounted near to the once splendid swimming pool. Her cruising days were over forever as she took on the role of one of Her Majesty’s troopships.

At 0400 hrs on 17 June 1940 she anchored slightly off Saint Nazaire at Charpentier Roads and began evacuating soldiers from the British Expeditionary Force along with some RAF men and a few civilians.

There is no completely accurate figure for the number aboard but it is estimated at a little over 7,000 people. Four bombs hit in total. One was a bull’s eye, dropping straight down the funnel and exploding in the engine room. At 4.15 p.m., less than twenty minutes later, the Lancastria rolled onto her port side and made her way, bow first, to her grave on the seabed.

The crew and passengers appeared not to panic while abandoning the sinking liner and, incredibly, singing was heard as the ship went down (‘Roll Out the Barrel’ and ‘There Will Always Be An England’). It is estimated between 4,500 and 5,000 people died that day. Thankfully, however, this left around 2,500 people who were rescued. One reason that Lancastria history is not well known is that Winston Churchill felt the country’s morale could not bear the burden of such terrible news, and newspapers were ordered not to print the story. The Lancastria lies in 26 meters of water off St Nazaire.

To return to my first meeting, Mr Healy welcomed me and explained what it was to be a Cub Scout. In my experience he was liked by every Cub in the pack and had what I can only describe as a special gift of being able to make each individual Cub feel special. His assistant, Dermot Richardson, was of a similar manner and he tutored me in the requirements for qualification. It wasn’t too long before all the tests were passed. Eventually the big day arrived and I was ready. Two lines of Scouts formed up facing each other on two sides of the hall and us Cub Scouts formed a line across the end, completing a U-shape of the full troop. At the open end of this formation, the leaders took up their positions. Immediately in front of the leaders a flag bearer held the Troop Flag in a horizontal position. The Scouts, some of them new members of the troop and some former Cubs, were first to be ‘invested’. We were, of course, practised in the ceremonial procedure at a couple of weekly meetings previously. Just like everyone else, when my turn came I marched smartly up to the flag and placed my left hand on it. At the same time I raised my right hand to shoulder height, making the Cub Scout sign with my right hand, and recited the ‘Cub Scout Promise’. Coming to attention, the official blue and yellow neckerchief was placed around my neck and the uniform cap on my head by Mr Healy. We exchanged salutes and I about-turned and returned to my ‘Six’ as a fully-fledged Cub Scout.

Our Cub Pack had about forty members between the ages of eight and eleven years. The membership was subdivided into groups of six. Each ‘Six’ was allocated a colour by which they were identified and each Cub wore a triangular badge of the appropriate colour on the upper left sleeve of his uniform sweater. In charge of each ‘Six’ was a ‘Sixer’ (appropriately enough) and he had the distinction of wearing two yellow stripes on his sleeve. He had an assistant to help him who proudly wore one yellow stripe. The overall boy leader or Senior Sixer was distinguished by three stripes and he was seen to be the link between the members of the pack and the adult leaders. This gave him a unique standing within the pack and was regarded by us new recruits as a ‘Super Cub’. When I joined, this elite Cub was Brendan Lawlor and his cousin Robert was my ‘Sixer’.

Outdoor activities played an important part of the programme throughout the year and so an appreciation of the changing faces of nature in all seasons was acquired. We went hiking on one or two Sundays a month to Larch Hill or the Pine Forrest on the outskirts of Dublin where we learned to prepare and light cooking fires. An important part of this skill was to leave the site with no trace of having been there. Sometimes cooking skills were learned the hard way. On one occasion, a Cub placed his unopened can of beans in a Billy Can of water on the fire, not aware of the consequences. When the can exploded, raining beans upon us, he was quick to learn that this was not the correct method.

Winter hiking was particularly popular, perhaps because it tended to be more challenging. For a start, it was more difficult to find dry kindling to get a cooking fire going and keep it going if the weather changed to rain. Dinner plates were great for fanning a fire and keep up a good blaze. Snow was a different matter because, after the meal, we would have snowball fights or slide down the frozen snow-covered slopes on our enamelled steel dinner plates. The enamel on the plate soon became chipped from this unconventional use and the exposed metal rusted, which did not please our parents. Plates and mugs later became available which were made from aluminium and then plastic, which greatly reduced the rate of destruction.

For an eight-year-old boy, a night or two away from family and home was exciting. To spend it in the mountains was an adventure. I’m sure most people will never forget their first camping weekend. None of the fancy designer hiking and camping equipment that is now available existed. Some ex-military tents and haversacks were available but, as the Second World War was not long ended, some of this was in short supply in Ireland. Father had obtained a sailor’s knapsack, which was to be my haversack. With checklist in hand, Mother called out the items one by one and I scanned the array of items on the floor. ‘Blankets and blanket pins?’ I replied ‘Ok’. ‘Spare socks?’ ‘Ok.’ ‘Towel and soap?’ ‘Ok.’ And so it went on until she reached the end of the list which included all clothing and food items necessary to survive the weekend. With everything packed I lifted the bulging knapsack on to my left shoulder and staggered under the weight. ‘You should drive him to Aston’s Quay, he’ll never manage that lot,’ said Mother. Father replied, ‘Ach, he’ll be grand, he’s old enough to go camping, he’ll soon learn to carry what’s needed.’ He then showed me how to ‘shoulder’ the bag. Mother opened the hall door as father said ‘away yea go then, have a great time’. ‘Mind yourself son. Don’t forget to say your prayers’. That was Mother.

So off I went, along Benbulbin Road to board the number 22 bus at Mourne Road, which would bring me to O’Connell Street. Getting off the bus in town, the bag was once again ‘shouldered’ and I walked to Aston’s Quay where some of my fellow Cubs were already gathered. Mr Healy checked that we were all there and our bags were loaded on the bus for Tibradden. The journey out to the Dublin mountains wasn’t all that unfamiliar to us as we had often hiked the route. In fact, a hike usually started from Rathfarnham which was a couple of miles further back. There was still a mile or so to go, so as soon as our entire luggage was off the bus we headed off in what was called ‘Indian’ file. Keeping to the right-hand side of the winding rural road, our single line of excited Cubs advanced on Larch Hill. It seemed as if additional items were being added to my pack because every ten minutes it felt heavier.

It was great to see the entrance gates of the national campsite, but the most difficult part of the walk was still ahead. Encouraged on by our leaders, light-heartedly calling out ‘we’re nearly there boys’ we trudged the final half mile of rising, twisting road to the Cub Field. Finally I set my knapsack down against a barbed-wire sheep fence and felt a sense of achievement.

Immediately on arrival, each Six was allocated a tent and shown where to pitch it. ‘In the nearest river’ one cheeky Cub said. The older and more experienced Cubs removed the heavy tent from its valise and spread it out flat while those new to tent pitching were directed by the Sixer to assemble the main and ridge poles. With the poles in position on the canvas, the tent was raised. My job that day was to hold on to one of the poles and keep it vertical while others pulled on the guy ropes, spreading the canvas. Only the more senior Cubs were allowed drive the wooden pegs with what seemed to me at the time to be an enormous wooden mallet. Finally, the guy ropes were adjusted and the canvas became taut. Dermot Richardson inspected each tent and advised on any adjustments that were necessary to have the tent pitched perfectly. Part of each camper’s equipment was a ground sheet and each one of us spread this out to cover the grass floor in our allotted tent.

The next task was to prepare our beds. The two woollen blankets now had to be fashioned into a sort of large envelope. The first was laid out flat on the ground and the second blanket overlapped this to the halfway point. The uncovered half of the first blanket was then folded back over the second, again to the half way point and finally the protruding half of the second was folded over the first. The large blanket pins pierced through the four folds along the two long sides and across one short side. A badly made bed meant an uncomfortable night as cold air would enter the bag through the seams. This would be the standard way to make a camp bed for many years until the commercial sleeping bag became available. Each bed was then rolled from the bottom towards the top and the rolls placed neatly along one wall inside the tent. It was important to have these tasks completed before nightfall and, no matter how tired or hungry you might be, the first task was to select a suitable site and set-up camp.